-

Banno

30.6kPhilosophy is a jigsaw puzzle.

Banno

30.6kPhilosophy is a jigsaw puzzle.

Descartes thought the best way to finish the puzzle was to start by finding the corners. The corners are fixed, he thought, so if we get them in place, we can work our way around the edge by finding the straight edges, and work our way into the middle. He argued that "I think therefore I am" was a corner.

Other folk thought he was mistaken. They looked for other corners. A priori concepts, perhaps; or dialectic, or the Will, or falsification, or logic, language, choice... And on and on

Wittgenstein's contribution consists in his pointing out that this particular jigsaw does not have corners, nor edges. There are always bits that are outside any frame we might set up. And further, we don't really need corners and edges anyway. We can start anywhere and work in any direction. We can work on disjointed parts, perhaps bringing them together, perhaps not. We can even make new pieces as we go. -

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Perhaps life is like a jigsaw puzzle but not a static one, because the overall picture changes too sometimes as well.

You begin with edges, building up the picture with all the issues, or sometimes moving into the middle with the questions of whether there is a God, whether mind and body are separate, free will to create a systematic picture.

But sometimes when the picture is almost created it is inevitably wrong even though the parts had seemed to fit. This involves a whole new construction of belief. This process could last for a lifetime.

So, in a sense the picture can change so to continue the metaphor, perhaps it is like a jigsaw game on a digital device. Not only is it about finding parts but the screen image is mutating too.

As this goes on we may become trapped in a long game of looking for missing pieces and perhaps we won't even find them before the screen changes once again. And what will the picture be that is emerging: a beautiful watercolour picture illuminated by light or a gothic image of monsters and werewolves amidst dark, fiery shadows. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kWittgenstein's contribution consists in his pointing out that this particular jigsaw does not have corners, nor edges. There are always bits that are outside any frame we might set up. And further, we don't really need corners and edges anyway. We can start anywhere and work in any direction. We can work on disjointed parts, perhaps bringing them together, perhaps not. We can even make new pieces as we go. — Banno

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kWittgenstein's contribution consists in his pointing out that this particular jigsaw does not have corners, nor edges. There are always bits that are outside any frame we might set up. And further, we don't really need corners and edges anyway. We can start anywhere and work in any direction. We can work on disjointed parts, perhaps bringing them together, perhaps not. We can even make new pieces as we go. — Banno

More precisely, Wittgenstein pointed out that what we think is a jigsaw puzzle is not really a jigsaw puzzle. So we shouldn't call it a jigsaw puzzle, maybe call it a game instead. And all those philosophers who think they are doing a jigsaw puzzle, and are looking for pieces to fit together are self-deceived and will never get anywhere, because they think they're doing a jigsaw puzzle when they're not.

But then we could say the same thing about the game. Philosophers who think philosophy is a game are self-deceived. And so on, we could go, with any analogy as to what philosophy is. And what this indicates is that analogies do not work for describing what something is, they're only an attempt to tell you what the thing is like, as someone will always come along and show you how the thing is different from the other thing, therefore the other thing doesn't provide you with what the thing is, only some form of similarity, from the perspective of the person who makes the analogy. -

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Jack Cummins

5.7k

I think you are being rather concrete in your thinking. Perhaps you think that the idea of philosophy being a game undervalued the tasks of the philosophers. In some sense this is the case and it could arguably be seen as an arduous quest to climb a high mountain. But surely the philosopher's journey needs to be enjoyable too.

The idea of a game captures this element.

Of course the idea of a jigsaw puzzle is a metaphor. As someone with an arts based view I I find metaphors important for capturing truth. Also, even scientists build models, which are only models as well.

All pictures, models and paradigms are only representations of truth.

Of course, as philosophers we want to go beyond the shadows on the walls of Plato' s cave but even the most profound philosophical writing is limited by the constraints of the meaning of the words which form the key concepts. -

Olivier5

6.2kMore precisely, Wittgenstein pointed out that what we think is a jigsaw puzzle is not really a jigsaw puzzle. So we shouldn't call it a jigsaw puzzle, maybe call it a game instead. And all those philosophers who think they are doing a jigsaw puzzle, and are looking for pieces to fit together are self-deceived and will never get anywhere, because they think they're doing a jigsaw puzzle when they're not. — Metaphysician Undercover

Olivier5

6.2kMore precisely, Wittgenstein pointed out that what we think is a jigsaw puzzle is not really a jigsaw puzzle. So we shouldn't call it a jigsaw puzzle, maybe call it a game instead. And all those philosophers who think they are doing a jigsaw puzzle, and are looking for pieces to fit together are self-deceived and will never get anywhere, because they think they're doing a jigsaw puzzle when they're not. — Metaphysician Undercover

This sounds like an apology of incoherence. Just because one philosopher failed to have coherent thoughts doesn't mean others can't or shouldn't try to. -

180 Proof

16.4k

180 Proof

16.4k

Maybe ... aPhilosophy is a jigsaw puzzle.

Descartes thought the best way to finish the puzzle was to start by finding the corners. The corners are fixed, he thought, so if we get them in place, we can work our way around the edge by finding the straight edges, and work our way into the middle. He argued that "I think therefore I am" was a corner.

Other folk thought he was mistaken. They looked for other corners. A priori concepts, perhaps; or dialectic, or the Will, or falsification, or logic, language, choice... And on and on

Wittgenstein's contribution consists in his pointing out that this particular jigsaw does not have corners, nor edges. There are always bits that are outside any frame we might set up. And further, we don't really need corners and edges anyway. We can start anywhere and work in any direction. We can work on disjointed parts, perhaps bringing them together, perhaps not. We can even make new pieces as we go. — Bannotransfinite, strange-looping, fractalholographic jigsaw puzzle 'assembled' by one of its pieces: philosophers. :smirk: -

Mayor of Simpleton

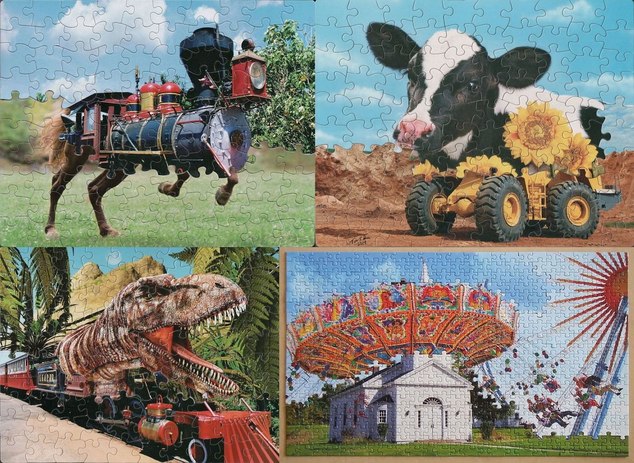

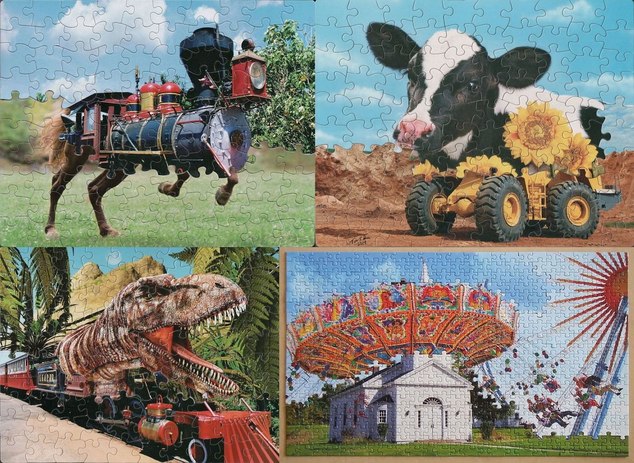

661Here are 4 examples of what can happen when a series of unrelated premises meet up in a philosophy forum.

Mayor of Simpleton

661Here are 4 examples of what can happen when a series of unrelated premises meet up in a philosophy forum.

Haven't we all experienced this sort of philosophy at one time or another... if not on a daily basis?

Perhaps the Ads and Mods care to comment here. ;)

-

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kThere are always bits that are outside any frame we might set up. — Banno

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kThere are always bits that are outside any frame we might set up. — Banno

Or pieces we don't yet know how to connect, that have no affordance in the work in progress. You can set those aside until their place is revealed, or you can set aside the work in progress for a while and take the orphan as a separate starting point, and then hope to join the two (or many) works together later. Not coincidentally, people doing a jigsaw together do both. Just noticing that two loose pieces go together, even if you don't know where the two of them together will end up, is progress. -

jgill

4kFrom the perspective of an elderly mathematician jigsaws are like doing a problem in a textbook (I never liked that) - difficult, but uninspiring, they've been solved hundreds of times before - while an uninhibited foray in which creativity is paramount is far more satisfying. Avoid those "jigsaw puzzles" that go round and round in philosophical arguments conducted thousands of times already. The probability of making a breakthrough is very, very small even if you are an intellect to be reckoned with. Instead, be creative and move into relatively unexplored territory. There you might succeed and produce something unique, even though it might be of low general interest. :cool:

jgill

4kFrom the perspective of an elderly mathematician jigsaws are like doing a problem in a textbook (I never liked that) - difficult, but uninspiring, they've been solved hundreds of times before - while an uninhibited foray in which creativity is paramount is far more satisfying. Avoid those "jigsaw puzzles" that go round and round in philosophical arguments conducted thousands of times already. The probability of making a breakthrough is very, very small even if you are an intellect to be reckoned with. Instead, be creative and move into relatively unexplored territory. There you might succeed and produce something unique, even though it might be of low general interest. :cool: -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kWe can start anywhere and work in any direction. We can work on disjointed parts, perhaps bringing them together, perhaps not. — Banno

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kWe can start anywhere and work in any direction. We can work on disjointed parts, perhaps bringing them together, perhaps not. — Banno

The appeal of edges and corners is that some of the directions you might go in are not available, so your search space is reduced -- or, rather, is reduced if you've sorted the remaining pieces in some way, but even if you haven't the number of criteria a piece could meet and be usable is reduced, so identifying add-onable pieces is simpler either way.

But you always have the option of not thinking of the pieces as fitting together at all, and the puzzle is just putting each piece in the right place, as if in a grid, which is curious. People do exactly that with corners and edges, but trying to do that with every piece would surely lead to a sort of combinatorial explosion, so instead we allow the work or works in progress to constrain our search.

Whether you think of next piece as add-onable or just as placeable, the whole process is inherently concurrent, which is also curious, and why puzzles can readily be worked on in multiple chunks and in parallel by multiple people. This would remain true even for a simplified form of puzzle that was a just a line or a snake, connecting pieces as in a chain.

(I'm not actually disputing your no-edges, making-new-pieces take, but you know I'm going to be fascinated by the nitty-gritty of how the problem is structured and how people actually solve these things, lots of which still applies to your open-ended construction.

You might be interested to know there was -- still is? -- a line of puzzles that billed themselves as the "world's hardest jigsaw puzzle": no picture of what you were making, no edge pieces, and a handful of extra pieces to throw you off.)

Avoid those "jigsaw puzzles" that go round and round in philosophical arguments conducted thousands of times already. — jgill

I think I fundamentally agree here. On the other hand, as you can see above, I can't help but find jigsaw puzzles and how people solve them interesting even if the particular puzzles themselves are old hat. Of course I've been known to find how people put on their socks interesting, so... -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k -

TheMadFool

13.8kPhilosophy as a jigsaw puzzle? Hmmmmm...So, are you expecting a picture to emerge after you've put all the pieces together? -

magritte

593Like many other games and puzzles, jigsaw puzzles have the peculiarity that a unique solution only comes easily when the pieces are few and large with obvious clues of fit neighboring pieces and the overall structure of the completed image.

magritte

593Like many other games and puzzles, jigsaw puzzles have the peculiarity that a unique solution only comes easily when the pieces are few and large with obvious clues of fit neighboring pieces and the overall structure of the completed image.

Growing complexity requires a second, higher type of meta-reasoning called strategy. Developing a strategy in solving puzzles becomes gradually more and more salient as complexity grows. As noted in a previous topic, chess is one of the best examples of this characteristic of puzzles. -

Mayor of Simpleton

661

Mayor of Simpleton

661

This was easier (and perhaps 'nicer') to portray it in this manner than attempting to post a can of farts to represent a series of unrelated premises being argued ad nauseam concluding with a 'the absolute real and only truth of all truths'.

I sort of look at philosophy more as a Rubik's cube that fights back, as if one was able to have within the cube both the Rock and Zeus combined when attempting to ascend a never ending mountain while being accompanied by a bitchy toddler asking every 30 seconds "are we there yet?".

So in a sense... hell isn't other people or yourself... it's everything and nothing at all. -

Banno

30.6kAfter this thread I started reading Mary Midgley. An aspect of philosophy to which she drew attention is the error of excepting al; the pieces to fit together as a neat whole.

Banno

30.6kAfter this thread I started reading Mary Midgley. An aspect of philosophy to which she drew attention is the error of excepting al; the pieces to fit together as a neat whole.

There need be noabsolute real and only truth of all truths — Mayor of Simpleton

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum