-

J

2.5k

J

2.5k

Is the "artwork" just the pebble or is the "artwork" the pebble plus the accompanying statement by the artist? — RussellA

"In Postmodernism, the boundary between the artwork and its accompanying statement is often deliberately blurred." — RussellA

But this is not only true of post-modernism. There is no such thing as an art work without an "accompanying statement." To suppose otherwise is to subscribe to the idea of an "innocent eye" which is somehow able to encounter an art work without knowing anything about it, or about art, disregarding the time and place of the encounter, and without bringing any cultural or individual experience to bear. Is there anyone on this thread who disagrees that this is a fiction?

Post-modernism perhaps is more deliberate about bringing this to our attention. -

RussellA

2.7kThere is no such thing as an art work without an "accompanying statement.....................................Is there anyone on this thread who disagrees that this is a fiction? — J

RussellA

2.7kThere is no such thing as an art work without an "accompanying statement.....................................Is there anyone on this thread who disagrees that this is a fiction? — J

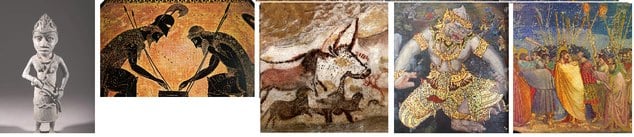

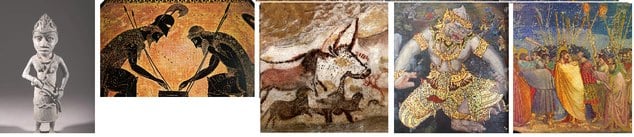

I know that these images have an aesthetic and are therefore art without knowing anything about the cultures they originated in.

The beauty of the aesthetic in art is that the observer only needs an innocent eye.

One problem with Postmodernism is that depends on its existence through the promotion of elitism within society, an incestuous Artworld that deliberately excludes the "common person" in its goal of academic exclusivity. -

J

2.5kI know that these images have an aesthetic and are therefore art without knowing anything about the cultures they originated in. — RussellA

J

2.5kI know that these images have an aesthetic and are therefore art without knowing anything about the cultures they originated in. — RussellA

Sure, so do I, but "the culture they originated in" is only one element of what I'm calling the "accompanying statement." My list of what constitutes an innocent eye was partial, but taking it as a starting point, do you feel that, when you encounter one of the above artworks (which are extraordinary, by the way, thanks!) you:

- know nothing about it? Really??

- know nothing about art yourself, from your own culture?

- are able to encounter the art in a way that is separate from a time and place?

- bring no cultural or individual experience to bear?

That would be, per impossibile, a truly innocent eye. And would we even be able to recognize art, using such an eye?

Innocence is a matter of degree, of course, but I think we should really try to notice what we already know, or think we know, when we see a work of art from an unfamiliar culture. -

I like sushi

5.4kMuch like the proposition of the Language Instinct I think the same can generally be said about having an Art Instinct. Such instincts may be no more than biological spandrels but irrespective of this they have come to possess meaning for the subjective human life -- where perhaps we live in nothing more than a room of smoke and mirrors!

I like sushi

5.4kMuch like the proposition of the Language Instinct I think the same can generally be said about having an Art Instinct. Such instincts may be no more than biological spandrels but irrespective of this they have come to possess meaning for the subjective human life -- where perhaps we live in nothing more than a room of smoke and mirrors! -

RussellA

2.7kMy list of what constitutes an innocent eye was partial, but taking it as a starting point, do you feel that, when you encounter one of the above artworks (which are extraordinary, by the way, thanks!) you:

RussellA

2.7kMy list of what constitutes an innocent eye was partial, but taking it as a starting point, do you feel that, when you encounter one of the above artworks (which are extraordinary, by the way, thanks!) you:

- know nothing about it? Really??

- know nothing about art yourself, from your own culture?

- are able to encounter the art in a way that is separate from a time and place?

- bring no cultural or individual experience to bear? — J

There are two distinct, separate and independent aspects.

On the one hand, there is the object as it exists independent of what one knows about it, and on the other hand there is what one knows about the object.

There is the object, for example a Lascaux cave painting.

There is what one knows about it. Estimated at around 17,000 to 22,000 years old, painted by the Magdalenian peoples, reindeer hunters who possibly engaged in cannibalism.

That the the object was possibly painted by a reindeer hunter has no bearing on the aesthetics of the object. The object has an aesthetic value regardless of whether it was painted by a reindeer hunter or a plant gatherer.

It is true that I know something about the Lascaux cave paintings, I know something about the Fauve artists of the 20th C and I have a particular cultural and individual experience, but all these have no effect on my seeing an object that has great aesthetic value.

In discovering an aesthetic in the Lascaux cave painting, my eye is innocent of any knowledge of facts and figures. -

J

2.5kYes, these are good discriminations. I tend to agree that biographical knowledge about the artist, for instance (hunter or gatherer? :smile: ), might not matter much to seeing a work as quality art.

J

2.5kYes, these are good discriminations. I tend to agree that biographical knowledge about the artist, for instance (hunter or gatherer? :smile: ), might not matter much to seeing a work as quality art.

The ultimate "innocence," which I'm arguing is an impossible limit-case, would have you looking at the Lascaux painting from a kind of "view from nowhere" -- suddenly, somehow, it appears before you, and you have no context in which to surmise it might be an art object, or for whom. Moreover, you yourself have no exposure to art up until this hypothetical moment.

I think we agree this is a fiction?

So the more practical question is, how much does each particular bit of knowledge you do bring to the painting affect your ability to have a pure or semi-innocent view? You say:

I know something about the Fauve artists of the 20th C and I have a particular cultural and individual experience, but all these have no effect on my seeing an object that has great aesthetic value. — RussellA

I find this hard to understand. Are you saying that your own cultural and individual experience of art, which you bring to the Fauve painting, has no effect on your perception of "great aesthetic value"? That anyone can see it? That seems so counter-intuitive that I think we must be somewhat at cross-purposes here. Maybe you could elaborate a bit? I think you're wanting to say that the painting contains, in and of itself, aesthetic value? -

Tom Storm

10.9kBut this is not only true of post-modernism. There is no such thing as an art work without an "accompanying statement. — J

Tom Storm

10.9kBut this is not only true of post-modernism. There is no such thing as an art work without an "accompanying statement. — J

We're talking about an actual, literal written statement. Most works are without such a thing.

suppose otherwise is to subscribe to the idea of an "innocent eye" which is somehow able to encounter an art work without knowing anything about it, or about art, disregarding the time and place of the encounter, and without bringing any cultural or individual experience to bear. — J

This is a different matter from a physical, prescriptive note from the artist. Also, I think there are plenty of people who are unfamiliar with artworks and have no idea how to engage with them or what they even are.

And by the way, an artist's statement may not be helpful. The artist might be mistaken about their work or might be deliberately trying to disrupt an interpretive framework, perhaps even being playful. A written statement may not support the work at all, but instead function as a provocative declaration that only adds to its ambiguity.

I once saw a broken wooden kitchen chair painted silver and black and arranged on display at an exhibition. There was a note from the artist. It read: 'The song is sung, but singing doesn’t help.' Such a message doesn’t add much to the work; it simply invites a lot of innocent speculation. The artist was later overheard saying, "I don’t know what it means. It just seemed to work." I'm not sure they were right about this.

One problem with Postmodernism is that depends on its existence through the promotion of elitism within society, an incestuous Artworld that deliberately excludes the "common person" in its goal of academic exclusivity. — RussellA

A common view but I think it misses the mark. There’s plenty of postmodern art created by graduate artists and unknown, underexposed, even struggling artists who see in postmodernism a vitality and opportunity for expression that you or others may not. -

J

2.5kWe're talking about an actual, literal written statement. Most works are without such a thing. — Tom Storm

J

2.5kWe're talking about an actual, literal written statement. Most works are without such a thing. — Tom Storm

I know, but I was pointing out that there's much less difference than at first appears, and suggesting we think about an "accompanying statement" more broadly. Because we can pose the same question about traditional art: How much information, if any, should be included as "part of" such a piece? At what point does information become necessary in order to see a Renaissance work as art? Leonardo may not have offered us a written statement, but his tradition did, or something very like it.

And then there's the name of the painting . . . part of the work?

I think there are plenty of people who are unfamiliar with artworks and have no idea how to engage with them or what they even are. — Tom Storm

No doubt. So, is that the sort of "innocent eye" we'd find desirable? Probably not. -

praxis

7.1kThe question for me then is if someone literally created a physical representation of a river that could be easily mistaken for a natural river then has that person produced Art? I guess for you you see no disparity other than in the creation (which does not fit into your definition of Art as an object). — I like sushi

praxis

7.1kThe question for me then is if someone literally created a physical representation of a river that could be easily mistaken for a natural river then has that person produced Art? I guess for you you see no disparity other than in the creation (which does not fit into your definition of Art as an object). — I like sushi

I don't see a contradiction. I do a lot of painting and the activity is unquestionably aesthetic. Think of an art form like music, it can be an aesthetic experience for the performer and the audience simultaneously.

So, you literally call the appreciation of natural beauty that moves someone Art but the Art 'is in the eye of the beholder' rather than the beauty? — I like sushi

If art is a social construct then it's in the eye of beholder's, I suppose.

What I think is interesting is the idea that the recognition of art may trigger 'aesthetic mode' in a conditioned response/constructed emotion sort of way. -

Tom Storm

10.9kI know, but I was pointing out that there's much less difference than at first appears, and suggesting we think about an "accompanying statement" more broadly. — J

Tom Storm

10.9kI know, but I was pointing out that there's much less difference than at first appears, and suggesting we think about an "accompanying statement" more broadly. — J

I understood that but I think this is stretching this idea too far, but we don’t have to agree.

And then there's the name of the painting . . . part of the work? — J

Only if it suits the critic's/owner's/seller's narrative...

At what point does information become necessary in order to see a Renaissance work as art? Leonardo may not have offered us a written statement, but his tradition did, or something very like it. — J

How we see and rate art is contingent on culture, education and values. We don’t just see a work as 'art', we have the potential to read into any work at many levels. If you’re just seeing Leonardo as a decorative thing, who cares? I’m personally not attracted to Leonardo’s work in general and I have superficial knowledge about his time or why he matters. So I haven't accessed any written information to help me form a view that he is 'special'. But I know he is rated... he's a brand, a popstar.

No doubt. So, is that the sort of "innocent eye" we'd find desirable? Probably not. — J

Depends on the purpose. Obviously no good for an art historian or dealer. I think the era of the dilettante expert and appreciator of culture and art may have ended. There used to be a pretence that the educated man (and later woman) would aim at a kind of Renaissance expertise and connoisseurship. I think cultural awareness of this kind used to be a form of virtue signalling, which is probably now left to pronouns and anti-colonisation lectures. :wink: -

J

2.5kI understood that but I think this is stretching this idea too far, but we don’t have to agree. — Tom Storm

J

2.5kI understood that but I think this is stretching this idea too far, but we don’t have to agree. — Tom Storm

Sure. It's a thought experiment, really. Nothing of great moment depends on it.

is that the sort of "innocent eye" we'd find desirable? Probably not.

— J

Depends on the purpose. Obviously no good for an art historian or dealer. — Tom Storm

What about for a philosopher? Do we want to argue that aesthetic value is neutral as regards the amount of information a viewer may have access to? -

Tom Storm

10.9kDo we want to argue that aesthetic value is neutral as regards the amount of information a viewer may have access to? — J

Tom Storm

10.9kDo we want to argue that aesthetic value is neutral as regards the amount of information a viewer may have access to? — J

Can you rephrase this? I'm assuming you're asking whether the aesthetic value of a work is independent from the information we have about it. You could easily write an essay on this. Personally, I tend to think that whatever value a work has is tied to who we are and what we know/experince. I don’t believe a work holds aesthetic value in itself, it’s always in relation to some criterion of value, whether basic or sophisticated. -

J

2.5kCan you rephrase this? — Tom Storm

J

2.5kCan you rephrase this? — Tom Storm

I'd better -- it was pretty ugly, sorry!

I'm assuming you're asking whether the aesthetic value of a work is independent from the information we have about it. — Tom Storm

That's more like it. Yes, that's what I was asking. And as a corollary: Does the aesthetic value change relative to what we know about a work? Like you, I think art is understood only in context, not in some idealized free space. Part of that understanding is aesthetic judgment. -

Tom Storm

10.9kI'd better -- it was pretty ugly, sorry! — J

Tom Storm

10.9kI'd better -- it was pretty ugly, sorry! — J

I've written my fair share of ugly sentences. :smile:

Yes, that's what I was asking. And as a corollary: Does the aesthetic value change relative to what we know about a work? — J

From a personal perspective, I would say that the more you know about something, the deeper your understanding and concomitant appreciation might be.

And aesthetic value changes with age and time. If you saw Psycho in 1960, it would have likely been shocking work of art. Some kids I know saw it and they found it dull and comic, and not in the right places.

I used to work for an antiquities dealer, selling Greek, Roman and Egyptian pieces and venerable, overpriced furniture. If you were a connoisseur of such things you might go into paroxysms of aesthetic delight over a Roman torso, which for someone else might just be some broken rubble. We never just relate to things as things; they are also objects of projected meaning. Or something like that. -

I like sushi

5.4kIf I am using the term Artwork I do not see how we can refer to a mountain as a Work of Art. Other than that, I am with you. My only qualm being in the specific instance of referring to something created as a work of art.

I like sushi

5.4kIf I am using the term Artwork I do not see how we can refer to a mountain as a Work of Art. Other than that, I am with you. My only qualm being in the specific instance of referring to something created as a work of art.

Obviously, you could argue that something created long ago may not have really been viewed/created as a piece of art (say a piece of furniture or a device for learning), but here we can appreciated the aesthetic quality of it and look upon it as a work of art (it was still made by someone).

I find nature beautiful for sure, but barring a belief in some Creator I do not view a mountain as Artwork. -

RussellA

2.7kThere’s plenty of postmodern art created by graduate artists and unknown, underexposed, even struggling artists who see in postmodernism a vitality and opportunity for expression that you or others may not. — Tom Storm

RussellA

2.7kThere’s plenty of postmodern art created by graduate artists and unknown, underexposed, even struggling artists who see in postmodernism a vitality and opportunity for expression that you or others may not. — Tom Storm

I agree that postmodern art is an opportunity for expression. I think less through the physical object but more through accompanying statements.

These unknown, underexposed postmodern artists, what exactly are they struggling against?

It seems that they are struggling to break into the Artworld, which is, as I see it, an exclusive club rather than a democratic institution. -

RussellA

2.7kThe ultimate "innocence," which I'm arguing is an impossible limit-case, would have you looking at the Lascaux painting from a kind of "view from nowhere" — J

RussellA

2.7kThe ultimate "innocence," which I'm arguing is an impossible limit-case, would have you looking at the Lascaux painting from a kind of "view from nowhere" — J

This "innocence" is common in human cognition.

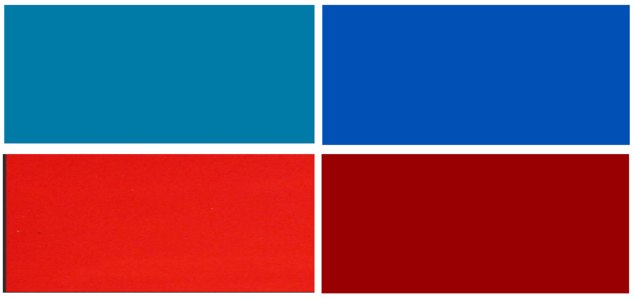

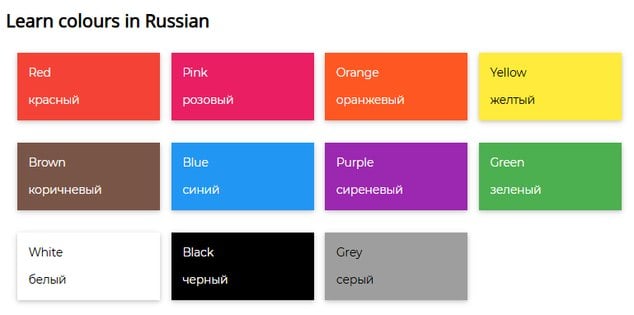

For example, when I look at grass, I don't think to myself, what colour should I see this grass as, should I see it as yellow, red, green or purple. I don't approach seeing colours with any preconceptions. In seeing the colour of an object my approach is no different to that of an innocent baby. I see the colour I see.

Similarly, with seeing an aesthetic in an object.

===============================================================================

Are you saying that your own cultural and individual experience of art, which you bring to the Fauve painting, has no effect on your perception of "great aesthetic value"? — J

Yes.

My belief is that every society in the past 17,000 years would recognise the aesthetic value in the Lascaux cave paintings. From the Sumerians through the Minoans up to the Greeks, Romans and into the 21st C, regardless of their particular religious, political or cultural beliefs.

===============================================================================

I think you're wanting to say that the painting contains, in and of itself, aesthetic value? — J

No.

"Beauty is in the eye of the beholder"

The object does not contain aesthetic value. The object contains a certain form in which an observer can see an aesthetic. -

Tom Storm

10.9kI agree that postmodern art is an opportunity for expression. I think less through the physical object but more through accompanying statements.

Tom Storm

10.9kI agree that postmodern art is an opportunity for expression. I think less through the physical object but more through accompanying statements.

These unknown, underexposed postmodern artists, what exactly are they struggling against?

It seems that they are struggling to break into the Artworld, which is, as I see it, an exclusive club rather than a democratic institution. — RussellA

I think the average person also sees the art world as elitist and hard to traverse. I'd say hardship is the primary struggle for most artists unless they gain a following, but that’s just as true for acting, music, and writing as it is for painting.

Art's definitely not democratic, however. It's more of a meritocracy. Exclusive club? It's a whole set of clubs, not just one, and some of them are not exclusive. But like any club, the level of its elitism depends upon the audience.

To succeed in art, it's not an art world you need to satisfy, it's the punters who wish to buy and hang your work. But the machinations of dealers and critics are a separate matter entirely. -

Tom Storm

10.9kFor example, when I look at grass, I don't think to myself, what colour should I see this grass as, should I see it as yellow, red, green or purple. I don't approach seeing colours with any preconceptions. In seeing the colour of an object my approach is no different to that of an innocent baby. I see the colour I see.

Tom Storm

10.9kFor example, when I look at grass, I don't think to myself, what colour should I see this grass as, should I see it as yellow, red, green or purple. I don't approach seeing colours with any preconceptions. In seeing the colour of an object my approach is no different to that of an innocent baby. I see the colour I see.

Similarly, with seeing an aesthetic in an object. — RussellA

I'd say this is inaccurate.

To begin with, an innocent baby doesn’t know what colours are or what they’re called. They need to be socialised and taught colour, just as they are taught shapes, and patterns and even their meanings and uses (e.g., 'blue for boys, pink for girls'). In the same way, our aesthetic isn’t in the object as much as it is our way of seeing, which is the product of contingent factors like our era, education, culture, perception, and senses. I'm colour-blind, so what I see is different from some others. I wouldn’t think there’s any such thing as an 'innocent' view. -

RussellA

2.7kTo begin with, an innocent baby doesn’t know what colours are or what they’re called. They need to be socialised and taught colour, just as they are taught shapes, and patterns and even their meanings and uses (e.g., 'blue for boys, pink for girls'). — Tom Storm

RussellA

2.7kTo begin with, an innocent baby doesn’t know what colours are or what they’re called. They need to be socialised and taught colour, just as they are taught shapes, and patterns and even their meanings and uses (e.g., 'blue for boys, pink for girls'). — Tom Storm

When stung by a wasp, you don't need to know the name "pain" before feeing pain. You feel pain regardless of what it is called.

Similarly with seeing colour, you don't need to know the name "cadmium blue" before seeing cadmium blue.

Similarly with having an aesthetic experience, you don't need to know the name "aesthetic experience" before having an aesthetic experience.

You need a name in order to communicate your subjective experience with other people, but you don't need a name to have that subjective experience. -

Tom Storm

10.9kI don't think so. Sure, you can see cadmium blue without knowing the name, but you only recognise it as cadmium blue (or find it meaningful) because you’ve learned to see it in certain ways and have been given a name and context. Otherwise, it’s just part of a blur of unfiltered input. Similarly, experiencing a work of art isn’t about perceiving colours or images innocently, without context. It’s context that shapes the perception and gives the aesthetic experience its meaning.

Tom Storm

10.9kI don't think so. Sure, you can see cadmium blue without knowing the name, but you only recognise it as cadmium blue (or find it meaningful) because you’ve learned to see it in certain ways and have been given a name and context. Otherwise, it’s just part of a blur of unfiltered input. Similarly, experiencing a work of art isn’t about perceiving colours or images innocently, without context. It’s context that shapes the perception and gives the aesthetic experience its meaning.

But perhaps we are too far apart on this matter. -

RussellA

2.7kSure, you can see cadmium blue without knowing the name, but you only recognise it as cadmium blue (or see it as meaningful) because you’ve learned to see it that way and have been given a name. Otherwise, it’s just part of a blur of unfiltered input. — Tom Storm

RussellA

2.7kSure, you can see cadmium blue without knowing the name, but you only recognise it as cadmium blue (or see it as meaningful) because you’ve learned to see it that way and have been given a name. Otherwise, it’s just part of a blur of unfiltered input. — Tom Storm

Perhaps we are too far apart on this matter.

Replacing "cadmium blue" by "pain"

Sure, you can feel pain without knowing the name, but you only recognise it as pain (or see it as meaningful) because you’ve learned to see it that way and have been given a name. Otherwise, it’s just part of a blur of unfiltered input.

I would have thought that our subjective feeling of pain was independent of language. In other words, does knowing the name of our pain change the subjective feeling? -

Jamal

11.8k

Jamal

11.8k

You need to do more research. What is shown there is closer to голубой than to синий. синий in English is “dark blue” or maybe “deep blue”.

The word “blue” has no equivalent in Russian; translations are approximate and misleading. If you actually take on board what I said, which is that Russians (Russian speakers) do not see light blue and dark blue as shades of the same colour, then you will understand why this is the case. -

Tom Storm

10.9kI would have thought that our subjective feeling of pain was independent of language. In other words, does knowing the name of our pain change the subjective feeling? — RussellA

Tom Storm

10.9kI would have thought that our subjective feeling of pain was independent of language. In other words, does knowing the name of our pain change the subjective feeling? — RussellA

But pain is not art, nor is it an interpretation of an object's aesthetic elements. So there's a problem with that comparison. This isn't a question about simple reactions to simple stimuli, it's a much more complex question concerning the aesthetics of an artwork.

By your reckoning, all we're doing is looking at shapes and colours, without context, composition, and experience. That strikes me as a very limited conception of aesthetics. If one did this to a work by Caravaggio where would we get?

Going back to pain for a moment, in a hospital, one of the first questions asked is, "On a scale of one to ten, how much does it hurt?" This reveals that pain alone isn’t self-interpreting; we need language and description to give it meaning, to locate it within a framework that allows for understanding, assessment, and response. Not to mention the subsidiary questions: is it a stabbing pain, an acute pain, a burning pain, a dull ache, and so on...

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum