-

hypericin

2.1kThat seems to fly in the face of evolutionary biology. We have three receptors in our eyes and one is specialised towards blue light which control our cycadian rhythm. — I like sushi

hypericin

2.1kThat seems to fly in the face of evolutionary biology. We have three receptors in our eyes and one is specialised towards blue light which control our cycadian rhythm. — I like sushi

When would a hunter gatherer actually need to distinguish blue from other colors? Red berries, green foliage, yellow flowers, but blue? It's not actually very relevant.

Our eyes are most sensitive to green, somewhat less to red, and far less to blue. -

javi2541997

7.3kAnother rabbit hole: constructed emotion theory and aesthetic experience. — praxis

javi2541997

7.3kAnother rabbit hole: constructed emotion theory and aesthetic experience. — praxis

A rabbit hole we can jump into, if you wish. :wink: -

I like sushi

5.4kCicadian Rhythm. Easily the most important as it regulates your body clock. This was fairly recently discovered to be far, far more sensitive to Blue light. Your Pineal Gland used to function as a kind of eye measuring this -- it regulates melatonin.

I like sushi

5.4kCicadian Rhythm. Easily the most important as it regulates your body clock. This was fairly recently discovered to be far, far more sensitive to Blue light. Your Pineal Gland used to function as a kind of eye measuring this -- it regulates melatonin.

As an aside, I think there is more than a good reason to correlate any increases in mental health issues with the prevalence of artifical light. This is especially relevant in an age of mobile devices!

Edit Note: Reds and Oranges are known to increase appetite -

RussellA

2.7kYes, Синий and голубой are basic colour terms and are thus seen as basic colours, not as shades of the same colour....The difference is that we think of ultramarine and cerulean as shades of blue, since in English that's what they are. — Jamal

RussellA

2.7kYes, Синий and голубой are basic colour terms and are thus seen as basic colours, not as shades of the same colour....The difference is that we think of ultramarine and cerulean as shades of blue, since in English that's what they are. — Jamal

The article "Russian blues reveal effects of language on colour discrimination" is about how people discriminate colours, not about how people perceive colours.

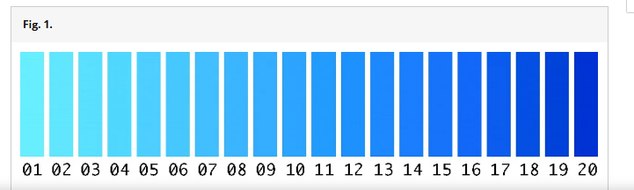

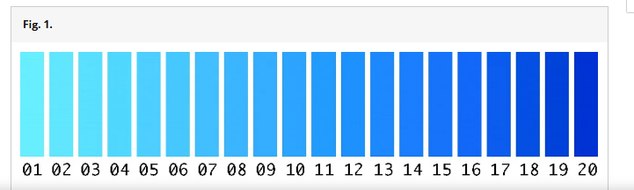

The article points out that in Russian there is no single word for the colours seen in Fig 1, and asks whether this means that Russians discriminate colours differently from non-Russians.

It seems certain that language does affect how people discriminate not only colours but observations in general. For example, someone looking at various artworks who is not aware of the concepts Modern and Postmodern will certainly categorise these artworks differently to someone who has learnt the concepts Modern and Postmodern.

It should be noted however that even through the Russian may not have a single word for the colours in Fig 1, and make the distinction between lighter blue голубой and darker blue Синий, this is a similar approach to English that makes the distinction between cerulean blue and ultramarine blue.

Again, because a linguistic distinction has been made between colours, it does not follow that there is a perceptual distinction. For example, an observer's perception of colour 9 in Fig 1 doesn't change as its name changes. An observer perceives the same colour regardless of whether it is called голубой in Russian, cerulean in English, bleu pâle in French or azzurro pallido in Italian.

The article notes that categories in language affect performance on simple perceptual colour task. This is understandable, in that someone not aware of the concepts Modern and Postmodern when looking at artworks and when asked to make judgements about these artworks will perform differently to someone who is aware of the concepts Modern and Postmodern.

These results demonstrate that (i) categories in language affect performance on simple perceptual colour tasks and (ii) the effect of language is online (and can be disrupted by verbal interference).

The article also concludes that performance can be disrupted by verbal interference. Also understandable, in that is someone was told that a particular artwork was an example of Modernism when in fact it was an example of Postmodernism, their immediate, instinctive judgment about the artwork would clearly be disrupted.

There is the strong and weak version of the Whorfian hypothesis. In linguistics, the Whorfian hypothesis states that language influences an observer's thought and perception of reality, and is known as linguistic relativity. The strong Whorfian hypothesis suggests that language determines a speaker’s perception of the world. The weak versions of the hypothesis simply state that language influences perception to some degree. The strong version has now been largely rejected by linguists and cognitive scientists, especially with the development of Chomskyan linguistics, although the weak version remains relevant. The weak version does allow for the translation between different languages.

https://www.britannica.com/science/Whorfian-hypothesis.

Speakers of different languages can look at colour 9 in Fig 1 and perceive the same colour regardless of its name. They are able to perceive the colour with the "innocent eye" described by Ruskin. He wrote that it is not the case that we can only perceive something if we already know what it is. This would inevitably lead into an infinite regression of perception and knowledge.

This is in opposition to Gombrich who argued that there is no "innocent eye". He wrote that it is impossible to perceive something that we cannot classify, thereby supporting the strong Whorfian hypothesis. But today the strong Whorfian hypothesis is generally not accepted. It it were accepted, it would lead into another chicken and egg situation, in that we couldn't even perceive colour 9 without knowing its name, and we couldn't know its name until we have perceived it.

The article makes sense that categories in language do affect a person's performance, but this is not saying that categories in language affect a person's perceptions. -

Jamal

11.8kThe article "Russian blues reveal effects of language on colour discrimination" is about how people discriminate colours, not about how people perceive colours. — RussellA

Jamal

11.8kThe article "Russian blues reveal effects of language on colour discrimination" is about how people discriminate colours, not about how people perceive colours. — RussellA

It's explicitly about both.

The article makes sense that categories in language do affect a person's performance, but this is not saying that categories in language affect a person's perceptions. — RussellA

That's explicitly what it's saying. -

RussellA

2.7kIt's explicitly about both. — Jamal

RussellA

2.7kIt's explicitly about both. — Jamal

The introduction to the article writes that they are investigating discrimination between colours, not the perception of colours

We investigated whether this linguistic difference leads to differences in colour discrimination.

Though of course, in order to be able to discriminate between colours 1 to 20 in Fig 1 they first they must be perceived. But this is not the topic of the article.

Kant's pure intuitions of time and space and pure concepts of understanding (the Categories) are not linguistic. The article is about linguistic discrimination. -

Jamal

11.8kKant's pure intuitions of time and space and pure concepts of understanding (the Categories) are not linguistic. The article is about linguistic discrimination. — RussellA

Jamal

11.8kKant's pure intuitions of time and space and pure concepts of understanding (the Categories) are not linguistic. The article is about linguistic discrimination. — RussellA

Why did you say this? Because I quoted Kant on intuition and concepts? Then you have misunderstood.

Otherwise, you're failing to understand ... well, everything really. Have fun! -

Moliere

6.5kKant's pure intuitions of time and space and pure concepts of understanding (the Categories) are not linguistic. The article is about linguistic discrimination. — RussellA

Moliere

6.5kKant's pure intuitions of time and space and pure concepts of understanding (the Categories) are not linguistic. The article is about linguistic discrimination. — RussellA

Ehhhh... yes, but no. But more importantly I'd say I'm persuaded to treat linguistic expression of the form "A is B" as a possible candidate for categorical language. It's one of the uses of the copula.

For purposes of this discussion it's fine to equate linguistic discrimination, like the Russian use of blue, with categories of distinction. At least I find it persuasive and any distinction which rests upon a difference between language/concept which rules out the study seems like special pleading.

Isn't it interesting that they have two distinct words for what we'd call "the same"?

That "the same" indicates some kind of categorization going on. Somehow these are related to us -- one is merely a relationship to another of the same underlying "blue". So they are "the same" -- that's the categorical use of "is"

And actually I think get gets along with my viewpoint so I'm rather inclined to accept it over a distinction between concepts and language. -

Moliere

6.5kI’m not keen on formalism. — Tom Storm

Moliere

6.5kI’m not keen on formalism. — Tom Storm

I like formalisms not for the traditional reason (somehow describing a universal experience due to our cognitive structures), but because they are ways of explicitly differentiating traditions. Though I think one must be careful not to confuse the formalism with what's being formalized -- which is to say that there are going to be counter-examples to any given formalism; in the manner of family resemblances, rather than universal conditions of beauty, this is not a fatal flaw, though. It's to be expected.

But this view of formalism is definitely different. In some ways I just mean it as "strict and clear attempted articulations of a tradition within the form of or towards the universal"; the attempt is usually for something others can see as something, if not necessarily beautiful at least not boring. -

RussellA

2.7kIsn't it interesting that they have two distinct words for what we'd call "the same"? — Moliere

RussellA

2.7kIsn't it interesting that they have two distinct words for what we'd call "the same"? — Moliere

The relationship between category and concept is interesting.

It seems that the Russians don't have one word for blue but have one word for pale blue голубой and one word for dark blue Синий. However, in English, we also have two distinct words, ultramarine for dark blue and cerulean for pale blue.

It seems that English is more extensive than Russian in that we also have a word for "blue", which the Russians don't seem to.

As regards the copula, "ultramarine is blue" and "cerulean is blue".

This is the beginning of categorization. Violet is a visible colour, blue is a visible colour, cyan is a visible colour, green is a visible colour, yellow is a visible colour, orange is a visible colour and red is a visible colour. Visible colour can then be categorized into violet, blue, cyan, green, yellow, orange and red.

Ultramarine is not the same as cerulean. Ultramarine is not the same as blue. The word "same" is not used as a copula, as a copula connects two different things.

Each of these is also a pre-language concept in that we don't need to know the names "violet" and "blue" in order to be able to discriminate between violet and blue.

It is the fact that we are able to discriminate between violet and blue, as we are able to discriminate between pain and pleasure, that enables us to develop a language that is able to categorise these discriminations.

It would indeed be strange if we could only perceive those things in the world that we happen to have names for. It would mean that if we had no name for something, then we couldn't perceive it, and if we couldn't perceive it then we couldn't attach a name to it. -

Moliere

6.5kIt seems that the Russians don't have one word for blue but have one word for pale blue голубой and one word for dark blue Синий. However, in English, we also have two distinct words, ultramarine for dark blue and cerulean for pale blue.

Moliere

6.5kIt seems that the Russians don't have one word for blue but have one word for pale blue голубой and one word for dark blue Синий. However, in English, we also have two distinct words, ultramarine for dark blue and cerulean for pale blue.

It seems that English is more extensive than Russian in that we also have a word for "blue", which the Russians don't seem to. — RussellA

Sorry, but I think that's a stretch in relation to the other explanation that our upbringing, which includes the language we speak, will influence our perceptions and conceptualizations thereof rather than judging one language-group as having "more extensiveness", whatever that might mean, from the perspective of some pre-linguistic conceptual perception. -

frank

19kIt would indeed be strange if we could only perceive those things in the world that we happen to have names for. It would mean that if we had no name for something, then we couldn't perceive it, and if we couldn't perceive it then we couldn't attach a name to it. — RussellA

frank

19kIt would indeed be strange if we could only perceive those things in the world that we happen to have names for. It would mean that if we had no name for something, then we couldn't perceive it, and if we couldn't perceive it then we couldn't attach a name to it. — RussellA

I think it's more that naming helps fix the mind on something, and remember it. If your visual field is filled with color, you'll remember the aspects of it that you have associated with a name. -

RussellA

2.7k"more extensiveness", whatever that might mean — Moliere

RussellA

2.7k"more extensiveness", whatever that might mean — Moliere

For example, English has a word for "blue" that the Russians don't seem to have.

It seems in general that English has a larger vocabulary than Russian, possibly because many English words were borrowed from Latin, French and German.

How many words are there in the Russian language?

There are many estimates. However, several of the larger Russian dictionaries quote around 130,000 to 150,000. Now, that’s a lot of Russian words. But if you compare it to English for instance – which has more than 400,000, then it’s not that bad. -

Moliere

6.5kThe point he's leading to is that the perception and appreciation of art are not separate, that art is meaningful all the way down. — Jamal

Moliere

6.5kThe point he's leading to is that the perception and appreciation of art are not separate, that art is meaningful all the way down. — Jamal

Yeah, I think that follows -- it need not be explicit or clear, which I imagine is usual, but I can't think of any other way we can distinguish a painting from simply painting a wall some color because that's the color walls are (off-white).

Frescos might be a better example there -- surely there's a difference between the wall before the Fresco and after the Fresco, and we see the artistic difference even though the picture on the wall is not a painting on the wall hanging in a frame, but a Fresco (a kind of painting).

What the eye does with light of varying wavelengths and intensities is none of our business—unless we're doing physiology or optics.

Yes, that's the gist of what I'm trying to get at with the idea of an aesthetic attitude -- looking at an artobject is to look at it as something aside from its presence, and aside from whatever role it may play within our own equipmentality. Something along those lines. -

RussellA

2.7kI think it's more that naming helps fix the mind on something, and remember it. If your visual field is filled with color, you'll remember the aspects of it that you have associated with a name. — frank

RussellA

2.7kI think it's more that naming helps fix the mind on something, and remember it. If your visual field is filled with color, you'll remember the aspects of it that you have associated with a name. — frank

True, but you don't need to know the names of the colours 1 to 20 in Fig 1 in order to see them. -

praxis

7.1kAh! I see. Not sure how relevant that is but it is something at least. — I like sushi

praxis

7.1kAh! I see. Not sure how relevant that is but it is something at least. — I like sushi

It’s highly relevant.

Imagine two abstract paintings of similar composition side by side on a wall. One of the paintings is colored with large blocks of black, white, red, and a little yellow. The other painting is only colored with large blocks of light blue and dark blue.

We may like the blue painting more but our eye will be naturally drawn to the ‘boldly’ colored painting. Why would that be if we can look at paintings with a “view from nowhere.” -

I like sushi

5.4kYou've lost me. I think I may have misunderstood though:

I like sushi

5.4kYou've lost me. I think I may have misunderstood though:

According to the theory (or study?) colors were added in about the same order across languages. That order being:

Red

Green or yellow

Both green and yellow

Blue

Brown

Purple, pink, orange, gray, etc. — praxis

Meaning in CURRENT texts rather than the first historical instances? I read this as meaning the first written instances recorded across all records. -

praxis

7.1k

praxis

7.1k

If I remember correctly, they examined the earliest written documents in various languages and looked for color names. They found that across languages the order of appearance was the same—red always showing up before blue, for instance. -

Jamal

11.8kI don't know, but I betcha I know what color this building is painted: it's goluboy. This is Catherine's Palace in St. Petersburg. — frank

Jamal

11.8kI don't know, but I betcha I know what color this building is painted: it's goluboy. This is Catherine's Palace in St. Petersburg. — frank

Right. When I asked Google in Russian what colour it was, the A.I. overview said, "Екатерининский дворец в Санкт-Петербурге имеет бело-голубой цвет фасадов," in which it says the facade is byelo-goluboy which means white and light blue (for want of an equivalent colour term). -

Jamal

11.8kYes, that's the gist of what I'm trying to get at with the idea of an aesthetic attitude -- looking at an artobject is to look at it as something aside from its presence, and aside from whatever role it may play within our own equipmentality. Something along those lines. — Moliere

Jamal

11.8kYes, that's the gist of what I'm trying to get at with the idea of an aesthetic attitude -- looking at an artobject is to look at it as something aside from its presence, and aside from whatever role it may play within our own equipmentality. Something along those lines. — Moliere

Totally. And even though Adorno hated Heidegger, I see a lot of common ground between them (and you) on this score. -

Moliere

6.5k

Moliere

6.5k

@RussellA, tho replying to @Jamal as a fellow in conversation whose saying things I agree with.

Well, you have two detractors of a sort. I've appreciated your creative efforts in proposing formalisms, but I think you've missed the point a few times now about the effect of language on perception, and even missed the point that I don't care if there's some difference between concepts/language with respect to this topic -- That Russians distinguish such and such means they see something different from us.

Perhaps their language is more extensive than English? -

Moliere

6.5kIt may be worth pointing out that recognizing that art is an end in itself does answer this current question of "use", but it does not provide the essence of art. After all, plenty of other things are ends in themselves, such as for example pleasure and friendship. By learning that aesthetic appreciation is not a means to an end, we have a better understanding of the phenomenon, but we have nevertheless not honed in on it in a truly singular way. — Leontiskos

Moliere

6.5kIt may be worth pointing out that recognizing that art is an end in itself does answer this current question of "use", but it does not provide the essence of art. After all, plenty of other things are ends in themselves, such as for example pleasure and friendship. By learning that aesthetic appreciation is not a means to an end, we have a better understanding of the phenomenon, but we have nevertheless not honed in on it in a truly singular way. — Leontiskos

I'm tempted to say a "double" way -- at least if negation is allowed.

Still, if people agree that art is an end unto itself that's progress. Something aside from "use". -

hypericin

2.1kSorry for the delay, I was camping and wasn't on here much.

hypericin

2.1kSorry for the delay, I was camping and wasn't on here much.

Someone who desires art will hold that what is more artistic is better than what is less artistic. — Leontiskos

Not true, even though "artistic" is a poor choice of words on my part.

A critic might say, "though the piece is obviously artistic, I don't care for it". This reads normally enough to me.

But "artistic" is a bad choice because it not only means "art-like, belonging to the category of art", there are strong positive connotations about quality. While the alternative "artsy" means "art-like" with weaker negative connotations. So I will just say "art-like".

"Someone who desires art will hold that what is more art-like is better than what is less art-like." Is clearly false. Better art does not belong to the category of art more than lesser art. Either it belongs, it doesn't, or it's marginal. Artists don't compete to create art that is more art-like, they compete to create better art.

Art-likeness is distinct from quality, and it, not quality, determines whether something is art or not. Do you agree? -

Moliere

6.5kI am curious what you think about my thoughts in the OP regarding the difference between painting and drawing? Where do you agree and disagree? Do you see much of a difference? — I like sushi

Moliere

6.5kI am curious what you think about my thoughts in the OP regarding the difference between painting and drawing? Where do you agree and disagree? Do you see much of a difference? — I like sushi

I feel overwhelmed at the amount of responses, and flattered. I've been reading along with everyone else, but would you mind re-expressing the thoughts?

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum