-

Janus

18kIt's not a matter of 'locating' them. That depiction is only because of the inability to conceive of anything not located in time and space. The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences and the abilities that it provides to discover facts which otherwise could never be known, indicate that numbers are more than just 'products of thought'. They provide a kind of leverage (that also being something discovered by a mathematician, namely, Archimedes). Which lead to many amazing inventions such as computers, and the like, which all would have been inconceivable a generation or two ago (as previously discussed.) — Wayfarer

Janus

18kIt's not a matter of 'locating' them. That depiction is only because of the inability to conceive of anything not located in time and space. The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences and the abilities that it provides to discover facts which otherwise could never be known, indicate that numbers are more than just 'products of thought'. They provide a kind of leverage (that also being something discovered by a mathematician, namely, Archimedes). Which lead to many amazing inventions such as computers, and the like, which all would have been inconceivable a generation or two ago (as previously discussed.) — Wayfarer

If we cannot coherently conceive of something being real without it existing somewhere at some time or everywhere at all times then that tells against your position.

If you want to say that the effectiveness of mathematics in science tells us anything about more than just how the world appears to us, then you are supporting the idea of a mind-independent reality. It seems obvious that number is immanent in the nature of things―once you have difference, diversity, structure then you have number. Time and space are quantifiable. But if you don't believe that difference, diversity, structure are mind-independently real or that time and space are mind-independently real―are you then

going to say that number is?

This is where I think the problem lies. They will say "I have direct knowledge of this, as do other Christians" (or whatever sect). You and I would largely reject this, but we also do not know their phenomenal experiences. Maybe they have... (this is unserious, but hopefully illustrates). — AmadeusD

Right, but religious experiences (which I of course would not deny that people do have) are not shareable, because they are "inner" experiences, not experiences of an "outer" "external" shared world. People may also experience hallucinations, and they are not considered to be empirically verifiable―if they were they would not be classed as hallucinations.

There are, on many reliable accounts, billions who do not find rape, murder, child abuse etc.. objectionable, when posited by a religious doctrine (or, rather, required by it). I suggest this is probably more prevalent than most in the West want to accept (and here we also need take into account the types within the West who perhaps feel these ways. We have enough abusers around for whom the Law is not a deterrent it seems). — AmadeusD

I think most people are against rape, murder, child abuse etc., when it comes to their own communities, to those they consider to be of their own kind. The word 'kindness' holds this implicit notion of kinship. People find it possible to accept violence against others if the others are understood to be enemies. But even then, look at the general disapproval of "war crimes'. The ideal would be if all people considered all others to be of their kind―humankind unbounded by religious bigotry and cultural antipathies. I don't deny that there are sociopaths, those lacking in normal human empathy, who don't have a problem with violent crimes.

If this is just a claim to an average, I think it's empirically true. I do not think your next claim follows. Among the 'smartest' people, you're likely to get more disagreement as each can bring more nuance and see different things in the same sets of data (or, different relations). I don't think this has much to do with feeling, though I am not suggesting we can avoid feelings when deciding on theories, for instance. — AmadeusD

I agree with you that it doesn't always predominately involve feeling (in the sense of wishing that things are some particular way) but I think in may cases it does, especially among the religious-minded. And remember I also said it can involve the hold that upbringing may have (although I guess that too might be counted as a kind of feeling―of for example attachment). Beyond that of course there will still be disagreement based on what different people find plausible when it comes to those matters the truth of which cannot be empirically determined (notably metaphysics and ontology).

Huh. I've had several give me what I think is a satisfactory answer. Something like:

"real" in relation to Universals obtains in their examples. The same as "red" which is obviously real, "three" can exist in the same way: In three things. Red exists in red things. I don't see a problem? — AmadeusD

Yes, but as I have said in this thread and many times elsewhere, I think number is found everywhere, which would mean it exists in the empirical world. Those who advocate for the reality of universals and number in some transcendental sense are the ones I had in mind―they are the ones who cannot say in what sense number could be real and yet not exist. (of course numbers considered as discrete entities, as opposed to number, are not encountered in the empirical world (except as numerals and of course they don't count because they are not themselves numbers, but are symbols of numbers).

We can agree, and do, agree on what's real in most contexts of ordinary usage. When it comes to metaphysics it's a different matter.

— Janus

This is important. "Real" is perfectly clear and useful in most contexts, because we know how to use it. — J

:up: Yes, and the interesting point seems to be that to agree on the meaning of 'real' would be to agree on what is real. The difficulty I have with those who posit the reality of transcendent things is that they are unable to say what "real" could mean in that connection. -

Wayfarer

26.2kIf you want to say that the effectiveness of mathematics in science tells us anything about more than just how the world appears to us, then you are supporting the idea of a mind-independent reality. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kIf you want to say that the effectiveness of mathematics in science tells us anything about more than just how the world appears to us, then you are supporting the idea of a mind-independent reality. — Janus

Empirical objects do have the appearance of being mind-independent — they confront us in space and time as separate objects — but that appearance is conditioned by (dependent on) the structures of perception and cognition. They are never given except as appearances to a subject. That is the main point of the mind-created world argument, as it pertains to 'the world' as the sum of sense-able particulars.

Mathematical truths are of a different order: they are independent of any individual mind in the sense that they’re the same for all who can reason — but they are only accessible to mind, not to the sensory perception (hence the subject of dianoia in Platonist terms, so of a 'higher' order than sensory perception.)

But if you don't believe that difference, diversity, structure are mind-independently real or that time and space are mind-independently real―are you then

going to say that number is? — Janus

As for time and space, they’re not mind-independent containers but, as Kant said, “forms of intuition” — the necessary preconditions of any experience. They are objectively real for the subject, in the sense that all appearances to us must be ordered in temporal sequence and spatial perspective. But that’s not the same as saying they exist as things-in-themselves apart from all possible subjects.

My point is not that the world is “all in the mind,” but that the only world we can speak of or investigate is the world as it appears through the conditions of human knowing — and that this doesn’t deny, but rather presupposes, that there is a reality in itself, although it lies beyond our possible experience. -

Janus

18kEmpirical objects do have the appearance of being mind-independent — they confront us in space and time as separate objects — but that appearance is conditioned by (dependent on) the structures of perception and cognition. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kEmpirical objects do have the appearance of being mind-independent — they confront us in space and time as separate objects — but that appearance is conditioned by (dependent on) the structures of perception and cognition. — Wayfarer

That is uncontroversial―of course appearances are mind-dependent, or body-dependent―however you want to frame it. It simply doesn't follow that what appears to us as objects in space and time are themselves mind-dependent ―you just don't seem to be able to understand that. They might be mind-dependent in themselves or they might not, and that is the question we cannot answer with any certainty.

They are never given except as appearances to a subject. That is the main point of the mind-created world argument, as it pertains to 'the world' as the sum of sense-able particulars. — Wayfarer

Again that is completely uncontroversial― if objects appear of course they appear to subjects (subjects being defined as percipients). Do the things which appear to us have their own existence independently of appearing to us? For me the answer would be "most likely they do". Of course I don't know for sure, but that seems to be the most plausible answer given everything we know about the world as it appears to be. If you don't think that is the most plausible answer, that's fine―you are entitled to that view, but don't pretend that there is a provable truth of the matter.

Mathematical truths are of a different order: they are independent of any individual mind in the sense that they’re the same for all who can reason — but they are only accessible to mind, not to the sensory perception (hence the subject of dianoia in Platonist terms, so of a 'higher' order than sensory perception.) — Wayfarer

Mathematical truths can be understood as possible logical entailments of the basic rules of number, and number can be understood to exist everywhere in the empirical world. It is a bit like chess―once the very simple rules of chess are established the possible series of combinations of the pieces are virtually infinite. We could say that there are a far greater number of those possible sequences of moves that have never occurred than those which have occurred. Do they exist out there somewhere? Or think of the simple iterative function which generates the Mandelbrot Set.

You've lost me once you start speaking of "higher order" because there can be no explanation of what it might be. We can have a feeling or sense of a higher order, but that is a different matter―it cannot be coherently subjected to analysis and discourse.

As for time and space, they’re not mind-independent containers but, as Kant said, “forms of intuition” — the necessary preconditions of any experience. They are objectively real for the subject, in the sense that all appearances to us must be ordered in temporal sequence and spatial perspective. But that’s not the same as saying they exist as things-in-themselves apart from all possible subjects.

You still seem to think I believe that the world is 'all in the mind', but I'm not arguing that. — Wayfarer

That time and space exist only for minds is itself not demonstrable, just as is the case with "things". That Kant said it is so does not make it true. I'm sorry but Kant is not my guru, I prefer to think for myself. That said I have read him and about him quite extensively so I'm well familiar with all the arguments. I know just where and why I part company with Kant.

I agree with Schopenhauer's critique― that there cannot be things in themselves if space and time exist only in relation to perception. Of course I don't accept that space and time exist only in relation to perception, because I find the idea that a completely unstructured undifferentiated "world in itself" could give rise to an unimaginably complex perceived world completely implausible― implausible as do I also find Schopenhauer's "solution" of a blind will. (And yes, I have fairly comprehensively read, and read about, Schopenhauer's philosophy― certainly enough to be well familiar with its central ideas. So I do understand his ideas, but I just don't agree with them).

I think you believe the world is an idea in some mind, not your mind or my mind, but some universal mind, probably not the mind of the Abrahamic God. If that is not what you believe then I confess I don't know what you are arguing. -

AmadeusD

4.3kI think most people are against rape, murder, child abuse etc — Janus

AmadeusD

4.3kI think most people are against rape, murder, child abuse etc — Janus

I have to say, I'm not so sure. Billions in communities outside the West see, for instance. Honour killings as a requirement, morally. All but the victim will agree. Just an example, but its these things I'm speaking out (while trying not to target religious thinking). This may ultimately not be all that important, though.

all others to be of their kind―humankind unbounded by religious bigotry and cultural antipathies — Janus

I agree. But even within communities who see each other as 'kin', horrifically violent actions take place with support of the law, and one's family, all the time. The femicides in China/Japan, the constant and unbearable mutilation, rape and murder of women in both Muslim and Hindu societies, the belief among certain sects of immigrants that these notions should be important to the West among other things tell me we could probably count more people OK with rape and murder than not, on a principle level. We would, obviously, disagree with them - but there are billions, as I understand. The death penalty for apostacy or atheism in seven countries seems to speak to this also... I do hope I am just a little over-alert to this, but I fear I am actually under playing it. We in the West tend to assume people share our moral outlooks, when that's probably one of the biggest areas of global disagreement and disharmony. We cannot co-exist with countries that deny women education, for instance, and still be 'moral' by our own lights.

I don't deny that there are sociopaths, those lacking in normal human empathy, who don't have a problem with violent crimes. — Janus

Unfortunately, I think a quote from Sam Harris bears repeating: There are good, and there are bad people. Good people do good things. Bad people do bad things. But to get a good person to do bad things, you need religion. Ah fuck, now I'm just bashing religion. Perhaps I shouldn't be so reticent. It is poison.

which cannot be empirically determined — Janus

We see it among that which can be, though. I'm unsure its particularly reasonable to presume everyone accepts "empirical evidence" as actual evidence. Those of us who understand what you're saying will do, but plenty (perhaps most) do not. They are skeptical of 'evidence' unless it agrees with their feelings. You and I would want to jettison this, and assess it against the claim, rather htan our feelings. I suggest this is far more common, and far more obvious than you are allowing here.

Yes,...but are symbols of numbers) — Janus

Nothing to quibble with here. I guess I just don't understand why the response I get isn't satisfactory. I don't know that anyone claims numbers exist outside examples of number. Or that colours exist outside examples of color (though, perhaps Banno would). -

AmadeusD

4.3kAgain, I don't see the problem? Why would we assume there's purpose to anything?

AmadeusD

4.3kAgain, I don't see the problem? Why would we assume there's purpose to anything?

That said, you may be interested in one of my profs work

I'm not moved by it, but if you're wanting to maintain some form of purpose or fundamental meaning to existence/the universe, he's good some good ideas. I just don't see why we would be pushing for it, if we can't see it already. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kIf we cannot coherently conceive of something being real without it existing somewhere at some time or everywhere at all times then that tells against your position. — Janus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kIf we cannot coherently conceive of something being real without it existing somewhere at some time or everywhere at all times then that tells against your position. — Janus

I can very easily conceive of something being real without existing somewhere at some time, or everywhere at all times. However, if explained to you, you dismiss such writing with phrases like "that passage reads like nonsense".

Do you recognize that this may indicate that you are in some way mentally handicapped? Or is this an attitudinal problem, a refusal to put in the effort required to understand such conceptions? Are you by any chance determinist, thinking that effort is not required to understand, believing that either the universe will make you understand, or not understand, as fate would have it?

Possibility for example, doesn't exist anywhere, at any time. -

Janus

18kI have to say, I'm not so sure. Billions in communities outside the West see, for instance. Honour killings as a requirement, morally. All but the victim will agree. Just an example, but its these things I'm speaking out (while trying not to target religious thinking). This may ultimately not be all that important, though. — AmadeusD

Janus

18kI have to say, I'm not so sure. Billions in communities outside the West see, for instance. Honour killings as a requirement, morally. All but the victim will agree. Just an example, but its these things I'm speaking out (while trying not to target religious thinking). This may ultimately not be all that important, though. — AmadeusD

Ok, you're right that "honour lkillings" are an exception. I guess if people are understood to have seriously transgressed in a context of very strict dogma, then they may become "othered" so that killing them then is seen as a duty.

But in such cases it would not be seen as murder, but as execution. It is also interesting to note that honour killing sometimes happens to women who have been raped―as though it must have been their fault and they are now forever defiled.

But even within communities who see each other as 'kin', horrifically violent actions take place with support of the law, and one's family, all the time. — AmadeusD

Yes such things of course do occur, but they are generally motivated by dogmatic religious views which effectively dehumanize the victim.

Unfortunately, I think a quote from Sam Harris bears repeating: There are good, and there are bad people. Good people do good things. Bad people do bad things. But to get a good person to do bad things, you need religion. Ah fuck, now I'm just bashing religion. Perhaps I shouldn't be so reticent. It is poison. — AmadeusD

I see no harm in individuals holding religious views of all kinds, provided they admit to themselves that they do not conflate faith with knowledge, that they understand that their faith is for themselves and should never be inflicted on others. So, it is institutionalized religion that is the problem, not the religious impulse perse, as I see it.

We see it among that which can be, though. I'm unsure its particularly reasonable to presume everyone accepts "empirical evidence" as actual evidence. Those of us who understand what you're saying will do, but plenty (perhaps most) do not. They are skeptical of 'evidence' unless it agrees with their feelings. You and I would want to jettison this, and assess it against the claim, rather htan our feelings. I suggest this is far more common, and far more obvious than you are allowing here. — AmadeusD

Yeah, I agree that many, I don't know about most, people are motivated by confirmation bias rather than the attempt to establish what is true or most reasonable to think. Some people just cannot accpet the idea that life may not be as they wish it to be.

Nothing to quibble with here. I guess I just don't understand why the response I get isn't satisfactory. I don't know that anyone claims numbers exist outside examples of number. Or that colours exist outside examples of color (though, perhaps Banno would). — AmadeusD

I think there are those who think numbers and universals are real independently of the particulars that instantiate them, well certainly if you can take them at their word they do. I cannot speak for @Banno but I suspect he would say that it depends on how you define colour. If you define it as a subjective experience then it would only exist as such. But if you allow that different wavelengths of light reflected from things are colours then they would be thought to exist independently of percipients.

Do you recognize that this may indicate that you are in some way mentally handicapped? — Metaphysician Undercover

No, because I know my command of the English language is such that I would be able to understand any coherent explanation. It doesn't follow though that I would necessarily agree with it. Are you one of those who think that you are so right that if anyone disagrees with what you write, they must therefore not understand it? -

Banno

30.6kThis response to this thread stands:

Banno

30.6kThis response to this thread stands:

We'll continue to use "colour" as we long have, regardless of peculiar and idiosyncratic stipulations of those on Philosophy forums.The thing is, you started this walk by yourself, and forgot about other people. That's the trouble with idealists - they are all of them closet solipsists." — Banno

Who here thinks honour killings are... honourable? -

AmadeusD

4.3kOk, you're right that "honour lkillings" are an exception. — Janus

AmadeusD

4.3kOk, you're right that "honour lkillings" are an exception. — Janus

I am not sure these are 'exceptions'. I rather think the Western, Enlightened model is the exception. That may lead to digression, so I'll just note that disagreement.

as though it must have been their fault and they are now forever defiled. — Janus

This is a particularly pernicious thing which only recently changed, even in the West. Marital rape was legal until like the 90s.

motivated by dogmatic religious views which effectively dehumanize them. — Janus

I agree, but that is considered a morally astute and respectable way of dealing with such things. *sigh*.

they understand that their faith is for themselves and should never be inflicted on others — Janus

This seems to me, a personal impulse and not institutional thing - the most wild of our religion offenders tend to have broken with orthodoxy and instead look to the scripts themselves. The 'old testament' types, that is (or, the Wahabis). Another issue is that the increasing, and somewhat aggressive attitude of religious immigrants is that the society into which they go should accommodate their beliefs - this, to me, being a matter of taking advantage of religious freedom (or misunderstanding it, i guess).

But if you allow that different wavelengths of light reflected from things are colours then they would be thought to exist independently of percipients. — Janus

I think they are used in both ways, but the answer to "What is red" is never a frequency. Largely because that's an unsupportable answer... Describing an experience is fine, but that's not something that 'red' can be, in this context. It is the weird stipulations of philosophy that has us calling a bundle of seemingly un-causally-related facts about perception, the world and our bodies "red" (notice, I need not enter into the discussion about perception for this oddity to become clear).

100% repulsive, both in reasoning and action. Utterly barbaric. -

AmadeusD

4.3k

AmadeusD

4.3k

The discussion stemmed from talk of what is 'real'. Some hold these views (possibly, most). We cannot ignore it. I find your response above emotionally satisfying, but essentially unhelpful and lazy. It happens and we should grapple with it (I think, obvs lol - do what you wish). I think this came directly from the idea that some religious will argue that Heaven is empirically real. The argument would run similar to that round hte fact that I have never seen x but rely on reports of it. I should do the same with their reports of Heaven. I rejected that this is a good way to determine real, but that it is clearly showing us that there is no universal acceptance of how to categorise things as real or unreal. -

Janus

18kI think they are used in both ways, but the answer to "What is red" is never a frequency. Largely because that's an unsupportable answer... — AmadeusD

Janus

18kI think they are used in both ways, but the answer to "What is red" is never a frequency. Largely because that's an unsupportable answer... — AmadeusD

I am out of time, but I just want to address this; the frequencies are in the science of optics referred to as being of different colours―the colours of refracted light we can see plus colours we cannot see, but some other animals can, and certain instruments can detect―ultraviolet and infrared. -

AmadeusD

4.3kThese rely on our reports of what they do to our perceptual system though. No instrument detects the 'red' humans do (and some humans don't, even on the same 'sense data'). The descriptions of frequencies as colors is a tertiary categorisation, i think. Primarily, we have an actual wavelength and the measure troughs and peaks, as esesntially a physical description.

AmadeusD

4.3kThese rely on our reports of what they do to our perceptual system though. No instrument detects the 'red' humans do (and some humans don't, even on the same 'sense data'). The descriptions of frequencies as colors is a tertiary categorisation, i think. Primarily, we have an actual wavelength and the measure troughs and peaks, as esesntially a physical description.

We then have 'light' as a descriptor of varying intensity and other things (speed, concentration etc..). We then, third, name the experience 'red' (in certain contexts). These are tenuous relationships to the word red.

I also understand that in optics, frequencies are not considered colors. They are considered causes of colors. They are considered a physical property of light which our brain interprets to be color x. Other animals may have totally different phenomenal experiences of the same wavelength (it seems we know they do).

"The Role of Human Perception

It's important to remember that color is a psychological and physiological phenomenon, not a fundamental physical property of light itself. Light waves have frequencies and wavelengths, but they don't have color until they are processed by the human eye and brain. Our eyes contain specialized cells called cones that are sensitive to different ranges of frequencies. When a mix of frequencies enters our eyes, our brain interprets the signals from these cones to create the perception of a particular color. This is why mixing different colored lights (additive mixing) or pigments (subtractive mixing) produces different results."

This can go awry, showing that color is a phenomenal experience. Calling frequencies colors is mere convenience for the lay-person. -

Banno

30.6kSome hold these views — AmadeusD

Banno

30.6kSome hold these views — AmadeusD

Sure, but they are wrong. So what's "unhelpful and lazy" might be allowing them to go ahead unopposed, or allowing their wrong ideas to decide what we do.

Not following your argument, but then I did miss a bit.

Notice that we - you and I - do not share a perceptual system? We have one each.These rely on our reports of what they do to our perceptual system though. — AmadeusD

What is it that we do share? -

AmadeusD

4.3kStructure of our perceptual system is what we share. When that isn't shared

AmadeusD

4.3kStructure of our perceptual system is what we share. When that isn't shared

Edit: Sorry mate, I hit submit by accident way before I was ready. Not trying to be sneaky or anything.

Sure, but they are wrong. — Banno

According to you (and me, to be clear). And we've been there. In any case my point is that ignoring them is how you get invaded by barbarians. So, i agree with what you've said at the top there (but subjectively), but I don't think waving it away as 'wrong' is going to help anyone. I find it lazy and somewhat irresponsible. If its so reprehensible, we should probably be aware and even possibly activated by its globally significant presence and more particularly the small incremental attempts to move these sorts of thinking into Western societes in the name of inclusion or religious tolerance.

Ill reply to the below comment on it's own to avoid the ridiculousness of chronologically out of place discussion. -

AmadeusD

4.3kThat might be true, but I did specify structure. The structures (and their structure, if you see what I mean) is essentially identical between us. Your biography, unless it includes injury, shouldn't alter that.

AmadeusD

4.3kThat might be true, but I did specify structure. The structures (and their structure, if you see what I mean) is essentially identical between us. Your biography, unless it includes injury, shouldn't alter that.

We share a 'direct of best fit' type of organ-based perception. We are aware that others can have aberrant structure or detail within this system. So those people don't share the same system, and they don't see what we report to be Red.

We don't always report the same thing, either. -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

I have a bit of a bee in my bonnet about "real" at the moment. So I hope you won't mind if I suggest that statement needs to be modified. I agree that there is no established way of categorising Heaven as real or not. But there is pretty much universal acceptance about how to categorise some other things as real. Unicorns, for example, forged paintings, dramatic performances. There is no single way of categorizing things as real or not. It depends on what kind of thing you are talking about. The same applies to questions of existence (which is what the issue of Heaven comes to). Numbers don't exist in the same way that tables and chairs do.I rejected that this is a good way to determine real, but that it is clearly showing us that there is no universal acceptance of how to categorise things as real or unreal. — AmadeusD -

J

2.5kReal" is perfectly clear and useful in most contexts, because we know how to use it.

J

2.5kReal" is perfectly clear and useful in most contexts, because we know how to use it.

— J

Real is authentic, not fake, the real deal. Reality is distinguished from delusion, illusion or duplicity. — Wayfarer

Well, yes, that works for many, perhaps most, contexts, as I was discussing with @Janus and @AmadeusD, above. But would you import it into a consideration of numbers, for instance? It seems like a bad fit. My contention is that, the more we enter metaphysics and epistemology, the less useful "real" is. I believe it's a placeholder or term of convenience for various other characteristics that can be more precisely stated. And to make matters worse, those other characteristics vary from tradition to tradition, while "real" remains constant, as if it could cover all of them.

But, as we've said, my view depends on there not being a story in which "real" did have a correct usage, which it lost. This is a specifically philosophical objection. Other uses of "real" observe different constraints.

to agree on the meaning of 'real' would be to agree on what is real. — Janus

And the question is, in what direction does the justification go? Do we discover a knowledge or nous of a certain sort of thing, and say, "This is real", based on what "real" means? Or do we have a term, "real", which we then attempt to match with certain sorts of things in order to discover what it does or could mean? -

Wayfarer

26.2kBut would you import it (designation of 'real') into a consideration of numbers, for instance? It seems like a bad fit. My contention is that, the more we enter metaphysics and epistemology, the less useful "real" is. — J

Wayfarer

26.2kBut would you import it (designation of 'real') into a consideration of numbers, for instance? It seems like a bad fit. My contention is that, the more we enter metaphysics and epistemology, the less useful "real" is. — J

Would that be because metaphysics is generally considered archaic by modern philosophy?

I've posted an excerpt from Bertrand Russell on universals in the Idealism in Context thread which can be reviewed here:

Reveal]Consider such a proposition as 'Edinburgh is north of London'. Here we have a relation between two places, and it seems plain that the relation subsists independently of our knowledge of it. When we come to know that Edinburgh is north of London, we come to know something which has to do only with Edinburgh and London: we do not cause the truth of the proposition by coming to know it, on the contrary we merely apprehend a fact which was there before we knew it. The part of the earth's surface where Edinburgh stands would be north of the part where London stands, even if there were no human being to know about north and south, and even if there were no minds at all in the universe. ... But this fact involves the relation 'north of', which is a universal; and it would be impossible for the whole fact to involve nothing mental if the relation 'north of', which is a constituent part of the fact, did involve anything mental. Hence we must admit that the relation, like the terms it relates, is not dependent upon thought, but belongs to the independent world which thought apprehends but does not create.

This conclusion, however, is met by the difficulty that the relation 'north of' does not seem to exist in the same sense in which Edinburgh and London exist. If we ask 'Where and when does this relation ["north of"] exist?' the answer must be 'Nowhere and nowhen'. There is no place or time where we can find the relation 'north of'. It does not exist in Edinburgh any more than in London, for it relates the two and is neutral as between them. Nor can we say that it exists at any particular time. Now everything that can be apprehended by the senses or by introspection exists at some particular time. Hence the relation 'north of' is radically different from such things. It is neither in space nor in time, neither material nor mental; yet it is something [real].

It is largely the very peculiar kind of being that belongs to universals which has led many people to suppose that they are really mental. We can think of a universal, and our thinking then exists in a perfectly ordinary sense, like any other mental act. Suppose, for example, that we are thinking of whiteness. Then in one sense it may be said that whiteness is 'in our mind'. ...In the strict sense, it is not whiteness that is in our mind, but the act of thinking of whiteness. The connected ambiguity in the word 'idea', which we noted at the same time, also causes confusion here. In one sense of this word, namely the sense in which it denotes the object of an act of thought, whiteness is an 'idea'. Hence, if the ambiguity is not guarded against, we may come to think that whiteness is an 'idea' in the other sense, i.e. an act of thought; and thus we come to think that whiteness is mental. But in so thinking, we rob it of its essential quality of universality. One man's act of thought is necessarily a different thing from another man's; one man's act of thought at one time is necessarily a different thing from the same man's act of thought at another time. Hence, if whiteness were the thought as opposed to its object, no two different men could think of it, and no one man could think of it twice. That which many different thoughts of whiteness have in common is their object, and this object is different from all of them. Thus universals are not thoughts, though when known they are the objects of thoughts. — Bertrand Russell, The World of Uhiversals

Russell makes a simple but important point about universals: things like the relation “north of” or the quality “whiteness” are real, but they’re not located in space or time, and they’re not just mental events.

Here’s the gist of his argument in four steps:

[1] Independence from mind – The truth of “Edinburgh is north of London” doesn’t depend on anyone thinking it; it would hold in a mindless universe.

[2] Non-spatiotemporal status – ‘North of’ isn’t in either city, and it’s not in space or time like physical objects are.

[3] Act vs. object of thought – Thinking of whiteness is a mental act in time; whiteness itself is not the act but the object of that act.

[4] Universality preserved – If whiteness were just a thought, it would be particularized (your thought now, my thought then), and couldn’t be the same across different thinkers and times.[/quote]

I'll go back to the original contention: that numbers (and other abstracta) are real but not existent in the sense explained by Russell. Empiricism attempts to ground mind-independence in the empirical domain - situated in space and time, instrumentally detectable and measurable. But the reality of such objects are still necessarily contingent upon the act of measurment and the theories against which they're interpreted.

And furthermore, the ability to even conduct such observations itself depends on the grasp of intelligible relations which is itself a noetic or intellectual act. Whereas empiricism, with its equation of “mind-independent” with “detectable by instruments,” then treats the faculties which enable these abilities as if they are derivative from the processes they're investigating. And this, against the background of the methodological bracketing of the knowing subject and the structures of understanding. We end up with worldview that literally uses universals constantly (in mathematics, definitions, logical inferences) while denying their ontological standing. -

J

2.5kReading your response, I think I might not have been clear. I was saying that, if we talk about numbers as "real", we likely don't mean "as opposed to fake" or "genuine", or one of the other commonly useful construals of "real". That was what I called a "bad fit."

J

2.5kReading your response, I think I might not have been clear. I was saying that, if we talk about numbers as "real", we likely don't mean "as opposed to fake" or "genuine", or one of the other commonly useful construals of "real". That was what I called a "bad fit."

So if we don't use that construal, which one should we use? The schema you're laying out makes sense, and can clearly be useful in dividing up the conceptual territory, but would you want to argue that it's the correct use of "real" in metaphysics? That's what I'm questioning. I don't think metaphysics is the least bit archaic -- it's one of the most exciting areas of contemporary philosophy -- but I'm suggesting that we now have better terminology than an endless wrangle about what counts as "real."

And BTW, I think (most) universals are every bit as mind-independent as you do. But there we are: "mind-independent" is a property or characteristic we can get our teeth into. Adding ". . . and real" seems unnecessary. -

Janus

18kAnd the question is, in what direction does the justification go? Do we discover a knowledge or nous of a certain sort of thing, and say, "This is real", based on what "real" means? Or do we have a term, "real", which we then attempt to match with certain sorts of things in order to discover what it does or could mean? — J

Janus

18kAnd the question is, in what direction does the justification go? Do we discover a knowledge or nous of a certain sort of thing, and say, "This is real", based on what "real" means? Or do we have a term, "real", which we then attempt to match with certain sorts of things in order to discover what it does or could mean? — J

At first I thought you were suggesting that we might have a noetic intuition as to what's real and then define 'real' according to that intuition. then I wondered whether you were using nous in the modern sense of know-how.

Then I noticed that you were not suggesting defining "real' in terms of the nousy intution, but saying the nousy intuition might be thought to be real or not based on the meaning of 'real'.

Your second idea seems to make more sense, anyway. We can cite examples and say whether they qualify as real or not. It would really just be using examples to illustrate how the term is commonly used in various contexts. We might discover that some examples qualify as real in one context and not in another.

I think the takeaway is that we cannot hope to get a "one-size-fits-all" definition of 'real', or 'existent'. It seems the best we can do is hone in on a somewhat fuzzy sense of the term and hopefully sharpen that sense up a bit.

And BTW, I think (most) universals are every bit as mind-independent as you do. But there we are: "mind-independent" is a property or characteristic we can get our teeth into. Adding ". . . and real" seems unnecessary. — J

And in turn that begs the question as to what we might mean by "mind-independent'―a term that seems to be much more slippery than 'real'. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe schema you're laying out makes sense, and can clearly be useful in dividing up the conceptual territory, but would you want to argue that it's the correct use of "real" in metaphysics? — J

Wayfarer

26.2kThe schema you're laying out makes sense, and can clearly be useful in dividing up the conceptual territory, but would you want to argue that it's the correct use of "real" in metaphysics? — J

Sorry my remark about metaphysics was prompted by many of the comments made here about it, but you're right, it is a field that has made a comeback in current philosophy.

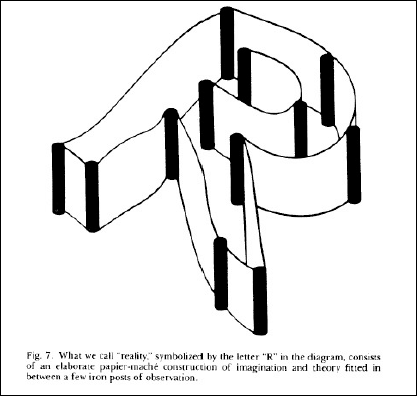

Consider this graphic from John Wheeler’s essay Law without Law:

The caption reads ‘what we consider to be ‘reality’, symbolised by the letter R in the diagram, consists of an elaborate paper maché construction of imagination and theory fitted between a few iron posts of observation’.

The “R” of reality is not given, but built from the accumulated record of acts of observation — each a scrap in the paper-mâché construction of the world.

My point about universals is that they are fundamental constituents of this ‘R’. I think Wheeler’s simile of ‘paper maché’ is a little misleading, as the tenets of physical theory are rather more ‘solid’ than this suggests. But regardless the elements of the theory are real in a different sense to its objects. They comprise theories and mathematical expressions of observed regularities. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kNo, because I know my command of the English language is such that I would be able to understand any coherent explanation. It doesn't follow though that I would necessarily agree with it. Are you one of those who think that you are so right that if anyone disagrees with what you write, they must therefore not understand it? — Janus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kNo, because I know my command of the English language is such that I would be able to understand any coherent explanation. It doesn't follow though that I would necessarily agree with it. Are you one of those who think that you are so right that if anyone disagrees with what you write, they must therefore not understand it? — Janus

Your replies are indicating that you do not understand what I write. They are not indicating that you do not agree with me. You say things like "that passage reads like nonsense", and "Gobbledygook".

The obvious conclusion is that either you are incapable of understanding me, or unwilling to try. Either way, to me, it appears as if you have an intellectual disability. I apologize for saying "mentally handicapped". Google tells me that this is outdated and offensive, and that I should use "intellectual disability" instead.

Do you recognize that replies like that would indicate to me that there is some sort of intellectual disability on your part?

Or, is it really the case, that you just disagree with me, but you are incapable of supporting what you believe, against my arguments, so you simply dismiss my arguments as impossible for you to understand, feigning intellectual disability as an escape?

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum