-

180 Proof

16.5k

180 Proof

16.5k

Philosophical naturalism (i.e. all testable explanations for nature, including the capabilities of natural beings (e.g. body, perception, reason), are completely constituted, constrained and enabled by (the) laws of nature) —> anti-supernaturalism, anti-antirealism. Re: Epicurus, Spinoza ... R. Brassier.P naturalism? As inphysicalistnaturalism? — Manuel -

Tom Storm

10.9kIf one were to put it this way: instead of consciousness arising from matter, matter arises within consciousness. In other words, reality is pure consciousness. It strikes me that, in a sense, Kant is a kind of dualist with his phenomena/noumena distinction. The “thing-in-itself,” however elusive, still functions as a foundational guarantee for our experience of phenomena. That seems less elegant than simply arguing that all is consciousness, with no independent “real world” needed that gives our experience of consciousness its shape. Thoughts?

Tom Storm

10.9kIf one were to put it this way: instead of consciousness arising from matter, matter arises within consciousness. In other words, reality is pure consciousness. It strikes me that, in a sense, Kant is a kind of dualist with his phenomena/noumena distinction. The “thing-in-itself,” however elusive, still functions as a foundational guarantee for our experience of phenomena. That seems less elegant than simply arguing that all is consciousness, with no independent “real world” needed that gives our experience of consciousness its shape. Thoughts?

My understanding is that Fichte had a similar issue and replaced noumenon with the notion of the “I.” He seems to avoid solipsism by positing the “I” as a transcendental consciousness that makes shared experience and intersubjectivity possible. This strikes me as wholly, or at least partly, compatible with Kastrup’s idea of Mind-at-Large, which he describes as non-metacognitive and the source of all consciousness. -

Wayfarer

26.2kIf one were to put it this way: instead of consciousness arising from matter, matter arises within consciousness. — Tom Storm

Wayfarer

26.2kIf one were to put it this way: instead of consciousness arising from matter, matter arises within consciousness. — Tom Storm

I'm trying to stick with epistemological idealism: matter arises within consciousness, because consciousness is a necessary pre-requisite to knowledge. Whatever we know, is disclosed through consciousness. This is, I hope, also consistent with the phenomenological attitude of attention to the fundamental characteristics of lived experience. As Husserl says, 'the world is disclosed by consciousness' - not that 'consciousness' is some kind of magic ingredient.

In other words, reality is pure consciousness. — Tom Storm

On face value, this collapses all manner of important distinctions. You might encounter such a statement in for example, Advaita Vedanta, but there it situated within a framework which stipulates the context and meaning. In another context it might mean something very different.

Kant is a kind of dualist with his phenomena/noumena distinction. — Tom Storm

He is! Perhaps @Mww can check in here, but I often refer to this passage:

The transcendental idealist... can be an empirical realist, hence, as he is called, a dualist, i.e., he can concede the existence of matter without going beyond mere self-consciousness and assuming something more than the certainty of representations in me, hence the cogito ergo sum. For because he allows this matter and even its inner possibility to be valid only for appearance– which, separated from our sensibility, is nothing – matter for him is only a species of representations (intuition), which are called external, not as if they related to objects that are external in themselves but because they relate perceptions to space, where all things are external to one another, but that space itself is in us. (A370) — A370

My belief about the in-itself is that it has caused a great deal of baseless speculation, even by many learned expositors of Kant's philosophy. I interpret it very simply - it is simply the world (object, thing) as it is in itself outside all cognition and perception of it. As soon as the thought arises, well, what could that be? - the point is already lost! We're then trying to 'make something out of it'. But, we don't know! Very simple. -

Manuel

4.4kPhilosophical naturalism (i.e. all testable explanations for nature, including the capabilities of natural beings (e.g. body, perception, reason), are completely constituted, constrained and enabled by (the) laws of nature) —> anti-supernaturalism, anti-antirealism. Re: Epicurus, Spinoza ... R. Brassier. — 180 Proof

Manuel

4.4kPhilosophical naturalism (i.e. all testable explanations for nature, including the capabilities of natural beings (e.g. body, perception, reason), are completely constituted, constrained and enabled by (the) laws of nature) —> anti-supernaturalism, anti-antirealism. Re: Epicurus, Spinoza ... R. Brassier. — 180 Proof

Ah ok. Got it. Thought the "p" was physical. :up: -

Janus

18kThen where is this relation? — RussellA

Janus

18kThen where is this relation? — RussellA

The relation just is the amount of actual space between them. That is, if you allow that space exists mind-independently, which I find it most plausible to think.

I find 'indirect/critical realism' (e.g. perspectivism, fallibilism, cognitivism/enactivism) to be much more self-consistent and parsimonious – begs fewer questions (i.e. leaves less room for woo-woo :sparkle:) – than any flavor of 'idealism' (... Berkeley, Kant/Schopenhauer, Hegel ... Lawson, Hoffman, Kastrup :eyes:) which underwrites my commitment to p-naturalism. — 180 Proof

:100:

When someone says that they perceive the colour red, science may discover that they are looking at an electromagnetic wavelength of 700nm.

Where in an electromagnetic wavelength of 700nm can the colour red be discovered? — RussellA

I think this way of speaking is misdirecting. We don't look at wavelengthts of light, wavelengths of light affect our eyes producing the perception of colours. So, red is not discovered in an electromagnetic wavelength of 700nm, as though we are somehow looking into light, light enters our bodies causing the discovery of colours.

It strikes me that, in a sense, Kant is a kind of dualist with his phenomena/noumena distinction. — Tom Storm

That would be one interpretation. As far as I recall form when I was reading Kant and reading about Kant quite intensively (although it was quite a few years ago now, so I could be getting it not quite right) Kant scholars are divided between a 'dual worlds' interpretation where there is the phenomenal (empirical) world and the noumenal world and a 'dual aspect' interpretation where there is one world with both a phenomenal and a noumenal aspect. -

RussellA

2.7kAnd did it occur to you that your understanding that she is bored might be erroneous? — L'éléphant

RussellA

2.7kAnd did it occur to you that your understanding that she is bored might be erroneous? — L'éléphant

Exactly.

"Esse est percipi" is translated as "to be is to be perceived".

But does this mean perceived through the sense, I perceive a loud noise, or perceived in the understanding, I perceive Mary is bored.

In my mind I perceive Mary to be bored. Therefore, from "esse est percipi", if I understand Mary to be bored, then in the world Mary's state of being is that of being bored.

But my understanding may be erroneous, as you say, and in the world Mary's state of being may not be that of being bored.

So I cannot depend on my understanding to know the true state of being in the world.

Therefore, "perceive" in "to be is to be perceived" cannot refer to the understanding but only to the sensibilities. -

RussellA

2.7kThe relation just is the amount of actual space between them. That is, if you allow that space exists mind-independently, which I find it most plausible to think. — Janus

RussellA

2.7kThe relation just is the amount of actual space between them. That is, if you allow that space exists mind-independently, which I find it most plausible to think. — Janus

Suppose a table exists mind-independently. A table is an object, not a relation.

Suppose space exists mind-independently. As with the table, then isn't space an object rather than a relation? -

RussellA

2.7kThe mind does make mistakes, but it is a lot cleverer than that. It judges the size of distant objects by comparing their height with other objects in the field of vision. It knows the actual height of the other objects, so it can work out the height of the unknown object.

RussellA

2.7kThe mind does make mistakes, but it is a lot cleverer than that. It judges the size of distant objects by comparing their height with other objects in the field of vision. It knows the actual height of the other objects, so it can work out the height of the unknown object.

So, yes, it creates a perception, but not necessarily a false one. — Ludwig V

If object A is 1.8 metre in size and object B is 1.7m in size, then there is a relation between their sizes. Does this relation exist in the mind, the world or both?

Every object in the Universe has a size, from a quark to a galaxy, so there is a relation between every possible pair of objects in the Universe.

If there were only 2 objects in the universe there is one relation. If there were only 3 objects in the universe there are 3 relations. If there were only 4 objects in the universe there are 6 relations. IE, in the Universe, there are more relations than objects.

If relations do exist in an ontological sense in the world, then there are more relations than actual objects.

Where did these extra relations come from? -

RussellA

2.7kNewton's laws cannot account for the reality of free will, where the cause of motion is internal to the body which accelerates. — Metaphysician Undercover

RussellA

2.7kNewton's laws cannot account for the reality of free will, where the cause of motion is internal to the body which accelerates. — Metaphysician Undercover

True. When thinking about the equation f=ma, in determinism force is a physical thing whereas in free will force is a mental thing.

In determinism there is no place for Aristotle's final cause, whereas in free will there is.

In determinism, an object moves because of a prior physical cause whereas in free will an object moves because of a future mental goal.

There is only one past, one present and several possible futures.

In determinism, the one past determines the one present.

In free will, as there is only one present, one of the several possible futures must have been chosen, and it is this choice that determines the one present.

Even in fee will, the present has been determined. -

Wayfarer

26.2kEven in fee will, the present has been determined. — RussellA

Wayfarer

26.2kEven in fee will, the present has been determined. — RussellA

What is a table to you, is a meal to a termite, and a landing place to a bird.

A table is an object, not a relation. — RussellA

Without wanting to wade into the endless quantum quandries, I really do not see how determinism can survive the uncertainty principle, nor the unpredictability of the quantum leap. This is what Einstein complained about, when he said 'God does not play dice'. But it seems irrefutable nowadays, that at a fundamental level, physical reality is not fully determined. The LaPlace Daemon model of inexorable past events determining a certain course has long gone. -

RussellA

2.7kWithout wanting to wade into the endless quantum quandries...................................But it seems irrefutable nowadays, that at a fundamental level, physical reality is not fully determined. — Wayfarer

RussellA

2.7kWithout wanting to wade into the endless quantum quandries...................................But it seems irrefutable nowadays, that at a fundamental level, physical reality is not fully determined. — Wayfarer

Neither do I. I am sure that science in the future will look back at current knowledge on quantum mechanics as we look back to alchemy.

But today not everyone agrees. Some believe in Superdeterminism, in that there are hidden variables that we do not yet know about.

Superdeterminism - Why Are Physicists Scared of It? - Sabine Hossenfelder -

RussellA

2.7kWhat is a table to you, is a meal to a termite, and a landing place to a bird. — Wayfarer

RussellA

2.7kWhat is a table to you, is a meal to a termite, and a landing place to a bird. — Wayfarer

True. As an Indirect Realist, I don't believe that tables exist in a mind-independent world, but only exist in the mind as a human concept.

However, some do believe that tables exist in a mind-independent world, and as such are objects rather than relations. -

sime

1.2kDeterminism can always survive on a theoretical level, in the sense that in ill-posed problem with more than one possible solution can always be converted into a well-posed problem with exactly one solution by merely adding additional premises.

sime

1.2kDeterminism can always survive on a theoretical level, in the sense that in ill-posed problem with more than one possible solution can always be converted into a well-posed problem with exactly one solution by merely adding additional premises.

However, the ordinary english meaning of "determine" does not refer to a property but to a predicate verb relating an intented course of action to an outcome. Ironically, an absolute empirical interpretation of "intention" is ill-posed and hence so is the empirical meaning of "determination", and is the reason why metaphysical definitions and defences of determinism are inherently circular.

For this reason, I think materalism, i.e a metaphysical commitment to objective substances, should be distanced from determinism - for if anything, a commitment to determinism looks like a metaphysical commitment to the objective existence of intentional forces of agency (i.e. spirits) that exist above and beyond the physically describable aspects of substances. -

RussellA

2.7ka commitment to determinism looks like a metaphysical commitment to the objective existence of intentional forces of agency (i.e. spirits) that exist above and beyond the physically describable aspects of substances. — sime

RussellA

2.7ka commitment to determinism looks like a metaphysical commitment to the objective existence of intentional forces of agency (i.e. spirits) that exist above and beyond the physically describable aspects of substances. — sime

A stone falls to the ground under gravity.

Materialism was the old term that just referred to matter, the stone and the Earth. Physicalism is the new term that refers to both matter and force, gravity. Though sometimes Materialism and Physicalism are still used interchangeably (Wikipedia - Physcialism)

The movement of the stone is determined by the force of gravity.

It is part of the nature of language that many words are being used as figures of speech rather than literally, such as "determined". Also included are metaphor, simile, metonymy, synecdoche, hyperbole, irony and idiom. -

Mww

5.4kKant is a kind of dualist with his phenomena/noumena distinction.

Mww

5.4kKant is a kind of dualist with his phenomena/noumena distinction.

— Tom Storm

He is! Perhaps Mww can check in here, but I often refer to this passage:

The transcendental idealist... can be an empirical realist, hence, as he is called, a dualist…. — Wayfarer

In the next paragraph of A370 is found his admission in favor of just that idealist/realist metaphysical dualism, but not because of the phenomena/noumena dichotomy, but rather, “….our doctrine removes all difficulty in accepting the existence of matter (…) or declaring it to be thereby proved in the same manner as the existence of myself as a thinking being is proved….”.

How the proofs arise, is given by the logical construction of the theory.

————

My belief about the in-itself is that it has caused a great deal of baseless speculation…. — Wayfarer

True enough. Dunno why, myself, for what it is, what it does, the reason for its conception, all about it, is in black and white, in the text. Same with that phenomena/noumena nonsense, I must say.

But you know how it goes…..opinions are like noses: everybody’s got ‘em. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThere is only one past, one present and several possible futures. — RussellA

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThere is only one past, one present and several possible futures. — RussellA

How is "several possible futures" consistent with determinism? If determinism is the case, then the future has alredy been determined, as well as the past, and there is only one actual future, not several possible futures.

We could conceptualize possibilities, as logical possibilities, or epistemological possibilities, but these would be imaginary, and not the actual future, which is what I think you are talking about. Then there would be no difference between past and future. But this is clearly not consistent with our experience.

In free will, as there is only one present, one of the several possible futures must have been chosen, and it is this choice that determines the one present.

Even in fee will, the present has been determined — RussellA

This doesn't make sense either.

A choice doesn't determine the present because it gives direction to a very small aspect in a very big context which is "the present". Even with the large number of choices being made by human beings, there is still a massive aspect of reality which is modeled by Newton's laws of motion, and this aspect is active without human choice. Commonly, by those who believe in free will, this activity is accounted for by "God's Will".

But today not everyone agrees. Some believe in Superdeterminism, in that there are hidden variables that we do not yet know about. — RussellA

Yeah, yeah, that's the ticket, "superdeterminism". How is that any better than "God's Will"? It's not, it's much worse. It requires an immaterial, non-spatialtemporal force, which is active throughout the entirety of the universe over the enirety of time. That sounds just like "God's Will". However, there is one big difference. "God's Will" is consistent with human experience of choice, free will, the known difference between past and future, and our knowledge of final cause, while "superdeterminism" is not. That's a very significant amount of evidence which superdeterminism simply ignores, in order to keep up the determinsit premise. Meanwhile, "God's Will" is a sound theory, supported by the experience of every human being who makes choices. And "superdeterminism" is just the pie-in -the-sky clutching at straws of deluded determinists.

I hope you can see the problem.

Here's an analogy. Consider Newton's first law. This law is applicable to a very large part (if not all) of empirical (observable) reality. We can ask why is this law so effective in its descriptive capacity.

You can answer that the law corresponds with a hidden feature of the universe, which extends to all areas of the universe, over all time, and this hidden feature ensures that Newton's first law will always be obeyed, everywhere, all the time. That is analogous with superdeterminism.

On the other hand, we can say that Newton's first law applies only to the aspects of the universe which our sense capacities allow us to observe, and evidence indicates to us that there is an extremely large portion of the universe which we cannot in any way observe with our senses (the future for example). And, since we cannot in any way observe this extremely large portion of the universe, to see how it behaves, we have no reason to believe that it behaves in the same way as the part which we can observe.

So, superdeterminism, instead of following the evidence which we do have, evidence of free will and final cause, simply makes a ridiculous conclusion based on no evidence, that there is a law of determinism, like Newton's first law, which extends throughout all features of reality, even those which we cannot possibly obsevre. -

sime

1.2kThe movement of the stone is determined by the force of gravity.

sime

1.2kThe movement of the stone is determined by the force of gravity.

It is part of the nature of language that many words are being used as figures of speech rather than literally, such as "determined". Also included are metaphor, simile, metonymy, synecdoche, hyperbole, irony and idiom. — RussellA

Yes, that is perfectly reasonable as an informal description of gravity when describing a particular case of motion in the concrete rather than in the abstract and as Russell observed, in such cases the concept of causality can be eliminated from the description. But determinism takes the causal "determination" of movement by gravity literally, universally and outside of the context of humans determining outcomes, and in a way that requires suspension of Humean skepticism due to the determinist's apparent ontological commitment to universal quantification over generally infinite domains.

Recall the game-semantic interpretation of the quantifiers, in which the meaning of a universal quantifier refers to a winning strategy for ensuring the truth of the quantified predicate P(x) whichever x is chosen . This interpretation is in line with the pragmatic sense of determination used in the language-game of engineering, where an engineer strategizes against nature to determine a product design that is correlated with generally favourable outcomes but that is never failure proof. (The engineer's sense of "winning" is neither universal nor guaranteed, unlike the determinist's).

If a determinist wants to avoid being charged with being ontologically commited to Berkeley's Spirits in another guise, then he certainly cannot appeal to a standard game-semantic interpretation of the quantifiers. But then what other options are available to him? Platonism? (Isn't that really the same as the spirit world?). He has no means of eliminating the quantifiers unless he believes the world to be finite. Perhaps he could argue that he is using "gravity" as a semantically ambiguous rigid designator, but in that case he is merely making determinism true by convention... -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

This is getting boring. There are no extra relations. They are spatial relations, so they must be in space, if anywhere.Where did these extra relations come from? — RussellA

There is very little to be learned from an endless series of the same puzzle. It's your puzzle, you answer it.

If we had progressed to some sort of intelligent discussion, it would have been worth it.

I'm here for the fun, not for exercises.

I've seen your other posts. You can do better than this.

Tell you what - you tell me where the end of the rainbow is and why I can never get to the horizon and why the only direction away from the north pole is southwards. -

Wayfarer

26.2kI've copied this passage you provided elsewhere because I would appreciate your perspective on the issue I've raised in the OP, specifically in two paragraphs after the heading The Matter with Matter.

Wayfarer

26.2kI've copied this passage you provided elsewhere because I would appreciate your perspective on the issue I've raised in the OP, specifically in two paragraphs after the heading The Matter with Matter.

RevealThe earlier philosophy of St Thomas Aquinas, building on Aristotle, maintained that true knowledge arises from a real union between knower and known. As Aristotle put it, “the soul (psuchē) is, in a way, all things,”² meaning that the intellect becomes what it knows by receiving the form of the known object. Aquinas elaborated this with the principle that “the thing known is in the knower according to the mode of the knower.”³ In this view, to know something is not simply to construct a mental representation of it, but to participate in its form — to take into oneself, immaterially, the essence of what the thing is. (Here one may discern an echo of that inward unity — a kind of at-one-ness between subject and object — that contemplative traditions across cultures have long sought, not through discursive analysis but through direct insight.) Such noetic insight, unlike sensory knowledge, disengages the form of the particular from its individuating material conditions, allowing the intellect to apprehend it in its universality. This process — abstraction— is not merely a mental filtering but a form of participatory knowing: the intellect is conformed to the particular, and that conformity gives rise to true insight. Thus, knowledge is not an external mapping of the world but an assimilation, a union that bridges the gap between subject and object through shared intelligibility.

By contrast, the word objective, in its modern philosophical usage — “not dependent on the mind for existence” — entered the English lexicon only in the early 17th century, during the formative period of modern science, marked by the shift away from the philosophy of the medievals. This marks a profound shift in the way existence itself was understood. As noted, for medieval and pre-modern philosophy, the real is the intelligible, and to know what is real is to participate in a cosmos imbued with meaning, value, and purpose. But in the new, scientific outlook, to be real increasingly meant to be mind-independent — and knowledge of it was understood to be describable in purely quantitative, mechanical terms, independently of any observer. The implicit result is that reality–as–such is something we are apart from, outside of, separate to.

One of the central flaws in Kant’s theory of knowledge is that he has blown up the bridge of action by which real beings manifest their natures to our cognitive receiving sets. He admits that things in themselves act on us, on our senses; but he insists that such action reveals nothing intelligible about these beings, nothing about their natures in themselves, only an unordered, unstructured sense manifold that we have to order and structure from within ourselves. — W. Norris Clarke - The One and the Many: A Contemporary Thomistic Metaphysics

So what I'm arguing is that it wasn't Kant who 'blew up the bridge', but the developments in the early modern period to which Kant was responding. As is well known, Kant accepted the tenets of Newtonian science, and sought to present a philosophy that could accomodate this, while still 'making room for faith' (his expression).

I suspect, but I don't yet know, that some of the modern analytical Thomists - I'm thinking Bernard Lonergan - might have explored this issue. Also a difficult book called Kant's Theory of Normativity, Konstantin Pollok (ref). -

Tom Storm

10.9kKant scholars are divided between a 'dual worlds' interpretation where there is the phenomenal (empirical) world and the noumenal world and a 'dual aspect' interpretation where there is one world with both a phenomenal and a noumenal aspect. — Janus

Tom Storm

10.9kKant scholars are divided between a 'dual worlds' interpretation where there is the phenomenal (empirical) world and the noumenal world and a 'dual aspect' interpretation where there is one world with both a phenomenal and a noumenal aspect. — Janus

Sounds like the Kantian conundrum equivalent to the Many-Worlds or Copenhagen Interpretations in QM. :razz: -

Janus

18kHa, yes it also seems to be related to the substance dualist/ aspect dualist polemic, but I think it's really quite different. Wasn't it Hegel who first alerted us to the fact that all ideas contain the seeds of polemic?

Janus

18kHa, yes it also seems to be related to the substance dualist/ aspect dualist polemic, but I think it's really quite different. Wasn't it Hegel who first alerted us to the fact that all ideas contain the seeds of polemic?

Seriously though, I think the MWI/ CI polemic is a far more complex issue―at least on the CI side. -

Janus

18kSuppose a table exists mind-independently. A table is an object, not a relation.

Janus

18kSuppose a table exists mind-independently. A table is an object, not a relation.

Suppose space exists mind-independently. As with the table, then isn't space an object rather than a relation? — RussellA

A relation is an object of thought. I think it can rightly be said that spatial relations are concrete (as opposed to purely conceptual). The distance (amount of space) between any two things at some "point in time" is not dependent on perception, even though the measurement of that distance can be said to be so.

Objects are generally thought of as being perceivable macro entities. I would say the space between two perceptible things is itself perceptible (although of course it will mostly not be a perceptually empty) space.

There is always going to be something that can be construed as ambiguous in anything we say, which may be interpreted as going against what we are saying. It's a lovely feature of natural language. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

So what I'm arguing is that it wasn't Kant who 'blew up the bridge', but the developments in the early modern period to which Kant was responding.

That's probably a more fair genealogical take. Clarke isn't really clear on which "version of Kant" he is referring to, and there are many. The reference is not followed up on in detail.

Most of the genealogies I've read, like Brad Gregory's The Unintended Reformation, D.C. Schindler's work, John Milbank's work, Amos Funkenstein's Theology and the Scientific Imagination from the Middle Ages to the Seventeenth Century all place the shift in the late middle ages, with Scotus and Ockham being the big figures, but also some German fideists who I can't recall the names of, as well as a somewhat gnostic strain in some forms of Franciscian spirituality. And the initial shifts are almost wholly theologically motivated, as opposed to relating to science or epistemology. The Reformation really poured gas on the process. The "New Science" comes later in a context that is already radically altered.

I've said before that Berkeley strikes me as a sort of damaged, fun house mirror scholasticism in a way. The analogy I would use is this. A big cathedral had collapsed. People had started building with the wreckage. They built their new foundation out of badly mangled and structurally impaired crossbeams from the old structure (e.g. "substance" and "matter"). Berkeley is pointing out to them that the materials they are using are badly damaged, but he also doesn't seem totally sure what they originally looked like before the collapse. (Now, a question of considerable controversy in this analogy is whether the cathedral collapsed because it was poorly built or because radical fundementalists dynamited it).

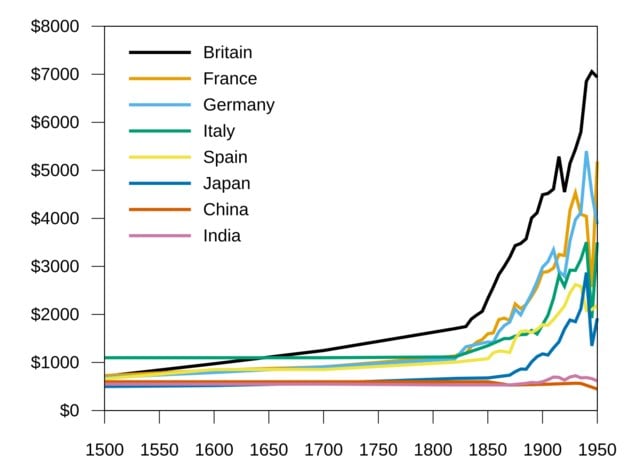

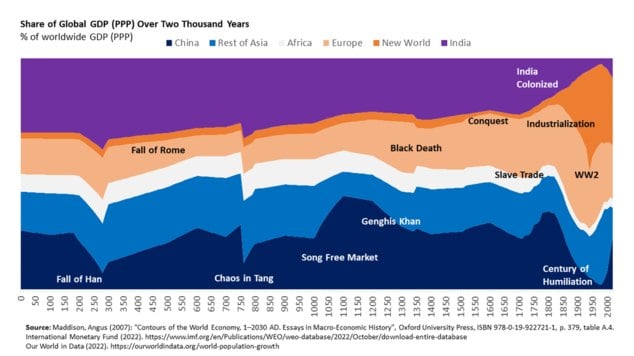

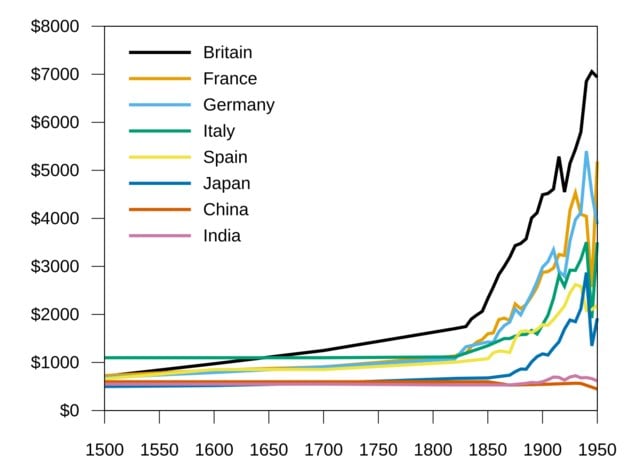

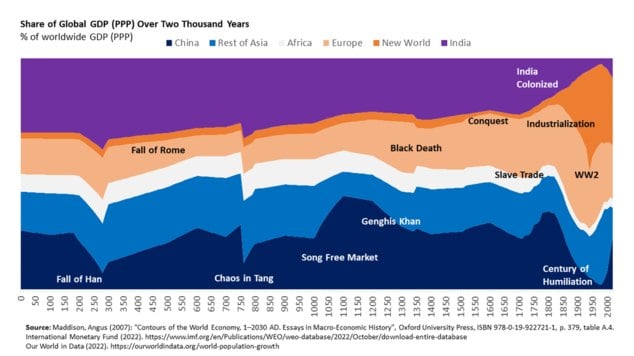

On a side note: I've also seen the argument that we are today largely the inheritors of a sort of "whig history" of science, that tells a story about how changes in philosophy (primarily metaphysics and epistemology, but also ethics) are responsible for the explosion in technological and economic growth that took place during the "Great Divergence," where Europe pulled rapidly ahead of China and India. A key argument for materialism is "that it works," and that it "gave us our technology." But arguably it might have retarded some advances. Some pretty important theories were originally attacked on philosophical grounds related to mechanism for instance.

Also, the timing is off. What you have is a fairly stable trend before and after the new science diffuses and then an explosion in growth with industrialization. The explosive growth actually coincides with the dominance of idealism, the sort of high water mark following Kant and Hegel. But I think it's probably fairer to say that the type of iterative experimentation driven development of industrialization was not that dependent on metaphysics. But this is relevant inasmuch materialism is still today (although less so) justified in terms of it being synonymous with science. -

Wayfarer

26.2kMany very good points there. I'm a bit more charitably inclined to Berkeley - as I think I said, his nominalism was a definite weakness, he had no coherent account of ideas. I have Gregory's book, but have only read John Milbank in essays and excerpts, but I think the Radical Orthodox have a very coherent story to tell, and that Scotus' univocity of being is right at the centre of it. This is what undermined the very possibility an heirarchy of being. But I'm never going to read Scotus or other medieval scholastics, there's only a couple of artifacts I'm interested in retrieving from the wreckage.

Wayfarer

26.2kMany very good points there. I'm a bit more charitably inclined to Berkeley - as I think I said, his nominalism was a definite weakness, he had no coherent account of ideas. I have Gregory's book, but have only read John Milbank in essays and excerpts, but I think the Radical Orthodox have a very coherent story to tell, and that Scotus' univocity of being is right at the centre of it. This is what undermined the very possibility an heirarchy of being. But I'm never going to read Scotus or other medieval scholastics, there's only a couple of artifacts I'm interested in retrieving from the wreckage. -

RussellA

2.7kHow is "several possible futures" consistent with determinism? — Metaphysician Undercover

RussellA

2.7kHow is "several possible futures" consistent with determinism? — Metaphysician Undercover

My intention was that from the viewpoint of a human observer, even in a deterministic world, they cannot know the future.

===============================================================================

Meanwhile, "God's Will" is a sound theory, supported by the experience of every human being who makes choices. And "superdeterminism" is just the pie-in -the-sky clutching at straws of deluded determinists. — Metaphysician Undercover

It depends on whether one believes that there is a divine entity or there is nothing over and above the physical.

===============================================================================

On the other hand, we can say that Newton's first law applies only to the aspects of the universe which our sense capacities allow us to observe................................we have no reason to believe that it behaves in the same way as the part which we can observe. — Metaphysician Undercover

We don't need to know whether Newton's Laws apply to those parts of the Universe that we don't observe, we only need to know that they apply to the parts of the Universe that we do observe.

===============================================================================

That sounds just like "God's Will". However, there is one big difference. "God's Will" is consistent with human experience of choice, free will, the known difference between past and future, and our knowledge of final cause, while "superdeterminism" is not. — Metaphysician Undercover

In Determinism, the changes a human makes to their present are determined by the past.

It seems that in In God's Will, the changes a human makes to their present are determined by the final cause, the unmoved mover. A human's will is free providing they use their will to move towards this final cause, this unmoved mover.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- What is the difference between subjective idealism (e.g. Berkeley) and absolute idealism (e.g. Hegel

- What does this philosophical woody allen movie clip mean? (german idealism)

- Idealism and "group solipsism" (why solipsim could still be the case even if there are other minds)

- Rationalism or Empiricism (or Transcendental Idealism)?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum