-

Truth Seeker

1.2kQuantum indeterminacy is irrelevant because at macroscopic levels all the quantum weirdness (e.g. quantum indeterminacy and superposition) averages out.

Truth Seeker

1.2kQuantum indeterminacy is irrelevant because at macroscopic levels all the quantum weirdness (e.g. quantum indeterminacy and superposition) averages out.

— Truth Seeker

Only sometimes, but not the important times. There are chaotic systems like the weather. One tiny quantum event can (will) cascade into completely different weather in a couple months, (popularly known as the butterfly effect) so the history of the world and human decisions is significantly due to these quantum fluctuations. In other words, given a non-derministic interpretation of quantum mechanics, a person's decision is anything but inevitable from a given prior state. There's a significant list of non-deterministic interpretations. Are you so sure (without evidence) that they're all wrong?

Anyway, it's still pretty irrelevant since that sort of indeterminism doesn't yield free will. Making truly random decisions is not a way to make better decisions, which is why mental processes do not leverage that tool. — noAxioms

Thank you for the thoughtful response. You raise a key point — that in chaotic systems, even minute quantum fluctuations could, in theory, scale up to macroscopic differences (the “quantum butterfly effect”). However, I think this doesn’t meaningfully undermine determinism for the following reasons:

1. Determinism vs. Predictability:

Determinism doesn’t require predictability. A system can be deterministic and yet practically unpredictable due to sensitivity to initial conditions. Chaos theory actually presupposes determinism - small differences in starting conditions lead to vastly different outcomes because the system follows deterministic laws. If the system were non-deterministic, the equations of chaos wouldn’t even apply.

2. Quantum Amplification Is Not Evidence of Freedom:

As you already noted, even if quantum indeterminacy occasionally affects macroscopic events, randomness is not freedom. A decision influenced by quantum noise is not a “free” decision — it’s just probabilistic. It replaces deterministic necessity with stochastic chance. That doesn’t rescue libertarian free will; it only introduces randomness into causation.

3. Quantum Interpretations and Evidence:

You’re right that there are non-deterministic interpretations of quantum mechanics - such as Copenhagen, GRW, or QBism - but there are also deterministic ones: de Broglie-Bohm (pilot-wave), Many-Worlds, and superdeterministic models. None of them are empirically distinguishable so far. Until we have direct evidence for objective indeterminacy, determinism remains a coherent and arguably simpler hypothesis (per Occam’s razor).

4. Macroscopic Decoherence:

Decoherence ensures that quantum superpositions in the brain or weather systems effectively collapse into stable classical states extremely quickly. Whatever quantum noise exists gets averaged out before it can influence neural computation in any meaningful way - except in speculative scenarios, which remain unproven.

So, while I agree that quantum indeterminacy might introduce genuine randomness into physical systems, I don’t see how that transforms causality into freedom or invalidates the deterministic model of the universe as a whole. At best, it replaces determinism with a mix of determinism + randomness - neither of which grants us metaphysical “free will.” -

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

Apologies for not seeing that question for months.I don't know enough about it to have an opinion about it. Please tell me more about how quantum events affect the weather. Is there a book you can recommend so I can learn more about this? Thank you. — Truth Seeker

There are whole books, yes. A nice (but still pop) article is this one:

https://www.space.com/chaos-theory-explainer-unpredictable-systems.html

The wiki version: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Butterfly_effect

The latter link in places talks specifically about the small initial differences being different quantum outcomes. The best known quantum amplifier is Schrodinger's cat, where a single quantum event quickly determines the fate of the cat, even if it isn't hidden in a box.

Even classical mechanics has been shown to be nondeterministic. Norton's dome is a great example of an effect without a cause. Nevertheless, a deterministic interpretation of physics would probably require hidden variables that determine the effect that appears uncaused.1. Determinism vs. Predictability:

Determinism doesn’t require predictability. A system can be deterministic and yet practically unpredictable due to sensitivity to initial conditions. — Truth Seeker

But it doesn't require determinism. Chaos theory applies just as well to nondeterministic interpretations of physics.Chaos theory actually presupposes determinism - small differences in starting conditions lead to vastly different outcomes because the system follows deterministic laws.

Well, deterministic equations would not apply. How about Schrodinger's equation? That function is very chaotic, and it is deterministic only under interpretations. like MWI.If the system were non-deterministic, the equations of chaos wouldn’t even apply.

Agree. So very few seem to realize this.2. Quantum Amplification Is Not Evidence of Freedom:

As you already noted, even if quantum indeterminacy occasionally affects macroscopic events, randomness is not freedom. A decision influenced by quantum noise is not a “free” decision — it’s just probabilistic. It replaces deterministic necessity with stochastic chance. That doesn’t rescue libertarian free will; it only introduces randomness into causation.

To me, freedom is making your own choices and not having something else do it for you. Determinism is a great tool for this, which is why almost all decision making devices utilize as much as possible deterministic mechanisms such as binary logic.

Superdeterminism is not listed as a valid interpretation of QM since it invalidates pretty much all empirical evidence. It's a bit like BiV view in that manner. The view doesn't allow one to trust any evidence.3. Quantum Interpretations and Evidence:

You’re right that there are non-deterministic interpretations of quantum mechanics - such as Copenhagen, GRW, or QBism - but there are also deterministic ones: de Broglie-Bohm (pilot-wave), Many-Worlds, and superdeterministic models.

MWI is a good example of chaotic behavior. You have all these worlds, and since weather and which creatures evolve are all chaotic functions, most of those worlds don't have you in it, or even humans. Most of those worlds don't have Earth in it. The deterministic part only says that all these possibilities must exist. There's no chance to any of them. But do they exist equally? That's a weird question to ponder.

No, I don't buy into MWI since I feel it gets some critical things wrong.

Of the two deterministic interpretations you mention, MWI is arguably the simplest, and DBB is probably the most complicated. This illustrates that 'deterministic' is not necessarily 'simpler'.None of them are empirically distinguishable so far. Until we have direct evidence for objective indeterminacy, determinism remains a coherent and arguably simpler hypothesis (per Occam’s razor).

At least under interpretations that support collapse.4. Macroscopic Decoherence:

Decoherence ensures that quantum superpositions in the brain or weather systems effectively collapse into stable classical states extremely quickly.

Yes, that what I meant by 'utilize as much as possible deterministic mechanisms'.Whatever quantum noise exists gets averaged out before it can influence neural computation in any meaningful way

In particular, no biological quantum amplifier has been found, and such a mechanism would very much have quickly evolved if there was any useful information in that quantum noise.except in speculative scenarios, which remain unproven.

Bottom line is that we pretty much agree with each other. -

Truth Seeker

1.2kThank you very much for the fascinating links you posted. I really appreciate your thoughtful follow-up. I agree that we’re largely converging on the same view.

Truth Seeker

1.2kThank you very much for the fascinating links you posted. I really appreciate your thoughtful follow-up. I agree that we’re largely converging on the same view.

Regarding Norton’s dome, I think it’s an interesting mathematical curiosity rather than a physically realistic case of indeterminism. It depends on idealized assumptions (e.g., perfectly frictionless surface, infinite precision in initial conditions) that don’t occur in nature. Still, it’s a useful illustration that even Newtonian mechanics can be formulated to allow indeterminate solutions under certain boundary conditions.

As for the quantum–chaos connection, yes - Schrödinger’s cat is indeed the archetypal quantum amplifier, though it’s an artificial setup. In natural systems like weather, decoherence tends to suppress quantum-level randomness before it can scale up meaningfully. Lorenz’s “butterfly effect” remains classical chaos: deterministic, yet unpredictable in practice because initial conditions can never be measured with infinite precision. Whether a microscopic quantum fluctuation could actually alter a macroscopic weather pattern remains an open question - interesting but speculative.

I agree with you that determinism is a great tool for agency. Even if all our choices are determined, they are still our choices - the outputs of our own brains, reasoning, and values. Indeterminacy doesn’t enhance freedom; it merely adds noise.

On superdeterminism: I share your concern. It’s unfalsifiable if taken literally (since it could “explain away” any experimental result), but it remains conceptually valuable in exploring whether quantum correlations might arise from deeper causal connections. I don’t endorse it, but I don’t dismiss it either until we have decisive evidence.

You put it well: the bottom line is that we mostly agree - especially that neither pure determinism nor indeterminism rescues libertarian free will. What matters is understanding the causal web as fully as possible.

Thanks again for such a stimulating exchange. Discussions like this remind me how philosophy and physics intersect in fascinating ways. -

noAxioms

1.7kKind of catching up on posts made since the 8 month dormancy.

noAxioms

1.7kKind of catching up on posts made since the 8 month dormancy.

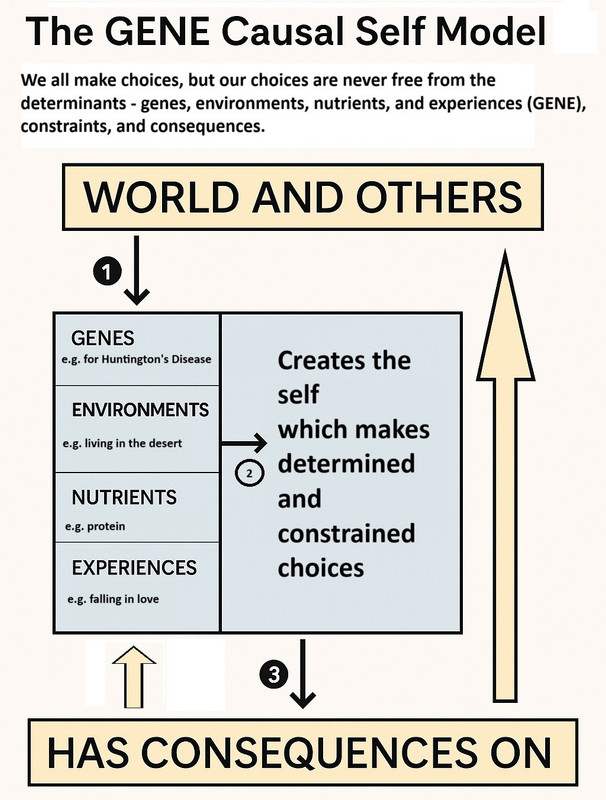

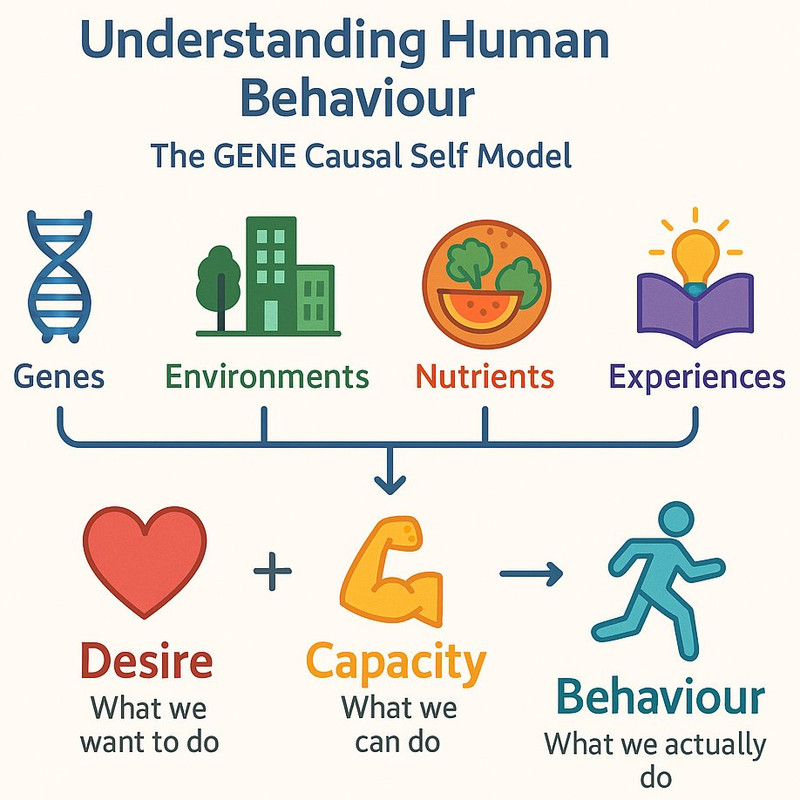

Depending on definitions, the two are not necessarily exclusive.Are we free agents or are our choices determined by variables such as genes, environments, nutrients, and experiences? — Truth Seeker

There you go. You seem to have a grasp on what choice actually is.Not for me. I feel many choices as I'm making them. I struggle with them, looking for a reason too give one option a leg up. — Patterner

Being able to review it amounts to different initial conditions.Technically, no, because the choice was made and we're not able to ever review it in this way. — AmadeusD

Billions of years?? It would be interesting, in say MWI, so see how long it take for two worlds split from the same initial conditions to result in a different decision being made. It can be one second, but probably minutes. Maybe even days for a big decision like 'should I propose marriage to this girl?'. But billions of years? No. Your very existence, let along some decision you make, is due to quantum events at most a short time before your conception.Theoretically, I think yes. But this involves agreeing that something billions of years ago would have to have happened differently.

Any determinism. That is also true under what is called soft determinism.If hard determinism is true, then all choices are inevitable — Truth Seeker

But as you've posted, determinism has little if anything to do with free will, or with moral responsibility. Substance dualism is a weird wrench in this debate. If there are two things, only the one in control is responsible for the actions of the body. So say if I get possessed by a demon (rabies say) and bite somebody, infecting them, am I responsible for that or is the demon? Is it fair to convict a rabid human of assault if they bite somebody? Kind of a moot point since they're going to die shortly anyway.

Sure. I will to fly like superman, but damn that gravity compelling otherwise.But I come at this from the opposite direction, it is the constraints of the hard physical world which restrict my strong free will. — Punshhh

Take away that and there would be no you have this freedom.Take that away and I would have near absolute freedom.

Yes. This is why determinism is irrelevant to the free will debate.Assume the mind is not equivalent to the brain. Could you have chosen differently? You still had a set of background beliefs, a set of conditioned responses, a particular emotional state and physical state, were subject to a particular set of stimuli in your immediate environment, and you had a particular series of thoughts that concluded with the specific ice cream order that you made. Given this full context, how could you have made a different choice? — Relativist

If a supernatural entity is making your choices, then not only is determinism false, but all of natural physics is false. A whole new theory is needed, and there currently isn't one proposed.

As has been pointed out, natural physics is regularly updated, and thus the current consensus view is not 'the truth'. But despite all the updates and new discoveries, one thing stands: Physics operates under a set of rules. We're still discovering those rules, but some definitions of moral responsibility require the lack of any rules. That's not ever going to be found to be the case.

I pretty much deny this. All evolved decision making structures have seemed to favor deterministic primitives (such as logic gates), with no randomness, which Truth Seeker above correctly classifies as noise, something to be filtered out, not to be leveraged.Because you're ignoring another major factor in Human Decision Making, namely randomness. — LuckyR

Sure, unpredictable is sometimes an advantage. Witness the erratic flight path of a moth, making it harder to catch in flight. But it uses deterministic mechanisms to achieve that unpredictability, not leveraging random processes.

Classical physics is a mathematical model, which some have proposed is reversible. No physics is violated by watching the pool balls move back into the triangle with all the energy/momentum transferred to the cue ball stopped by the cue.Regarding Norton’s dome, I think it’s an interesting mathematical curiosity rather than a physically realistic case of indeterminism. — Truth Seeker

Norton's dome demonstrates that classical mathematics is actually not reversible, nor is it deterministic, the way that the equations seem to be at first glance.

You have a reference for this assertion, because I don't buy it at all. Most quantum randomness gets averaged out, sure, but each causes a completely different state of a given system, even if it's only a different location and velocity of each and every liquid molecule.As for the quantum–chaos connection, yes

...

In natural systems like weather, decoherence tends to suppress quantum-level randomness before it can scale up meaningfully.

Evolution depends on quantum randomness, without which mutations would rarely occur and progress would proceed at a snails pace. There's a fine balance to be had there. Too much quantum radiation and DNA gets destroyed before it can be filtered for fitness. Too little and there's no diversity to evolve something better. -

Truth Seeker

1.2kThank you for asking for a source. You’re right that quantum effects can, in principle, influence macroscopic systems, but the consensus in physics is that quantum coherence decays extremely rapidly in warm, complex environments like the atmosphere, which prevents quantum indeterminacy from meaningfully propagating to the classical scale except through special, engineered amplifiers (like photomultipliers or Geiger counters).

Truth Seeker

1.2kThank you for asking for a source. You’re right that quantum effects can, in principle, influence macroscopic systems, but the consensus in physics is that quantum coherence decays extremely rapidly in warm, complex environments like the atmosphere, which prevents quantum indeterminacy from meaningfully propagating to the classical scale except through special, engineered amplifiers (like photomultipliers or Geiger counters).

Here are some references that support this:

1. Wojciech Zurek (2003). Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Reviews of Modern Physics, 75, 715–775.

Zurek explains that decoherence times for macroscopic systems at room temperature are extraordinarily short (on the order of (10^-20) seconds), meaning superpositions collapse into classical mixtures almost instantly.

DOI: 10.1103/RevModPhys.75.715

2. Joos & Zeh (1985). The emergence of classical properties through interaction with the environment. Zeitschrift für Physik B Condensed Matter, 59, 223–243.

They calculate that even a dust grain in air decoheres in about (10^-31) seconds due to collisions with air molecules and photons - long before any macroscopic process could amplify quantum noise.

3. Max Tegmark (2000). Importance of quantum decoherence in brain processes. Physical Review E, 61, 4194–4206.

Tegmark estimated decoherence times in the brain at (10^-13) to (10^-20) seconds, concluding that biological systems are effectively classical. The same reasoning applies (even more strongly) to meteorological systems, where temperature and particle interactions are vastly higher.

In short, quantum coherence does not persist long enough in atmospheric systems to influence large-scale weather patterns. While every individual molecular collision is, in a sense, quantum, the statistical ensemble of billions of interactions behaves deterministically according to classical thermodynamics. That’s why classical models like Navier–Stokes work so well for weather prediction (up to chaotic limits of measurement precision), without needing to invoke quantum probability.

That said, I fully agree with you that quantum randomness is crucial to mutation-level processes in biology - those occur in small, shielded molecular systems, where quantum tunnelling or base-pairing transitions can indeed introduce randomness before decoherence sets in. The key distinction is scale and isolation: quantum effects matter in micro-environments, but decoherence washes them out in large, warm, chaotic systems like the atmosphere.

Here are two images I created to help explain my worldview:

-

Athena

3.8kThat can be answered with yes or no, depending on how you look at it.

Athena

3.8kThat can be answered with yes or no, depending on how you look at it.

What's your answer? — frank

I answered yes, but that is conditional on having better information. Your question is tied to notions of good and evil and the tendency to judge people as good or evil. I do not believe we are good or evil, but we do the best we can with what we know, and our conscience and feelings of regret need good information so we can avoid those regrets.

Notice the word "conscience" meanings coming out of knowledge. -

LuckyR

740I pretty much deny this. All evolved decision making structures have seemed to favor deterministic primitives (such as logic gates), with no randomness, which Truth Seeker above correctly classifies as noise, something to be filtered out, not to be leveraged.

LuckyR

740I pretty much deny this. All evolved decision making structures have seemed to favor deterministic primitives (such as logic gates), with no randomness, which Truth Seeker above correctly classifies as noise, something to be filtered out, not to be leveraged.

Sure, unpredictable is sometimes an advantage. Witness the erratic flight path of a moth, making it harder to catch in flight. But it uses deterministic mechanisms to achieve that unpredictability, not leveraging random processes.

Exactly. I said you were "ignoring" randomness, your wording is "denying". Same thing. Just so you know, randomness exists, human denials notwithstanding. -

ProtagoranSocratist

278since "the past" is a done deal, then i have to answer no. Is this some sort of survey in relation to free will and determinism? "Free Will vs. Determinism" is one of my favorite philosophy conundrums, but it doesn't have a clear answer.

ProtagoranSocratist

278since "the past" is a done deal, then i have to answer no. Is this some sort of survey in relation to free will and determinism? "Free Will vs. Determinism" is one of my favorite philosophy conundrums, but it doesn't have a clear answer.

If you need me to elaborate, does wishing you made a different choice effect the past choices you made? If it doesn't, then the answer to the thread question and survey has to be a no. Argue with me all you like, but regret is an extremely common conundrum for humans and i'm rather experienced.

I guess "yes" is the right answer if there are alternate dimensions where people made different choices, but i don't know about those, so i can't answer yes. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9ksince "the past" is a done deal, then i have to answer no. Is this some sort of survey in relation to free will and determinism? "Free Will vs. Determinism" is one of my favorite philosophy conundrums, but it doesn't have a clear answer. — ProtagoranSocratist

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9ksince "the past" is a done deal, then i have to answer no. Is this some sort of survey in relation to free will and determinism? "Free Will vs. Determinism" is one of my favorite philosophy conundrums, but it doesn't have a clear answer. — ProtagoranSocratist

The question is not whether someone can change a choice which is already made, but whether one could have, at that time, the time when the choice was made, chose something different. -

ProtagoranSocratist

278The question is not whether someone can change a choice which is already made, but whether one could have, at that time, the time when the choice was made, chose something different. — Metaphysician Undercover

ProtagoranSocratist

278The question is not whether someone can change a choice which is already made, but whether one could have, at that time, the time when the choice was made, chose something different. — Metaphysician Undercover

We are talking about choices that could have only been made one time. -

L'éléphant

1.8k

L'éléphant

1.8k

And if we only had one choice at the time, then yes, the answer is no. But I have no idea why determinism works here. I actually do not understand the relationship between determinism and the choices we make. The choices we make in our daily life are nothing compared to what determinism has in store for us.Unless the universe (of determinant forces and constraints on one) changes too, I don't think so. — 180 Proof

Here are my examples:

1. We do not have a choice but to be a moral agent (not to say we will be moral, just that we either be moral or immoral).

2. We do not have a choice as to thoughts. We will have thoughts and imaginations. That's determined given our constitution.

4. Perception is determined, unless you're born a lump of flesh. We will perceive, period.

5. Desires are determined -- you can have difference desires, but you will have desires absolutely. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWe are talking about choices that could have only been made one time. — ProtagoranSocratist

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWe are talking about choices that could have only been made one time. — ProtagoranSocratist

What do you mean by "one time"? Do you deny that a person can deliberate, procrastinate, or otherwise delay in decision making, such that the choice occurs over a period of time? -

noAxioms

1.7kThe assertion under question:

noAxioms

1.7kThe assertion under question:

In natural systems like weather, decoherence tends to suppress quantum-level randomness before it can scale up meaningfully. — Truth Seeker

OK, very much yes on the rapid decay of coherence. But this does not in any way prevent changes from propagating to the larger scales in any chaotic system (such as the atmosphere). Sure, a brick wall is going to stand for decades without quantum interactions having any meaningful effect, but a wall is not a particulrly chaotic system.You’re right that quantum effects can, in principle, influence macroscopic systems, but the consensus in physics is that quantum coherence decays extremely rapidly in warm, complex environments like the atmosphere, which prevents quantum indeterminacy from meaningfully propagating to the classical scale except through special, engineered amplifiers (like photomultipliers or Geiger counters). — Truth Seeker

All three supporting only the first part I agreed with, yes. None of them support quantum differences propagating into macroscopic differences.Here are some references that support this:

1. Wojciech Zurek (2003). Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical.

Zurek explains that decoherence times for macroscopic systems at room temperature are extraordinarily short (on the order of (10^-20) seconds), meaning superpositions collapse into classical mixtures almost instantly.

2. Joos & Zeh (1985). The emergence of classical properties through interaction with the environment.

They calculate that even a dust grain in air decoheres in about (10^-31) seconds due to collisions with air molecules and photons - long before any macroscopic process could amplify quantum noise.

3. Max Tegmark (2000). Importance of quantum decoherence in brain processes.

Tegmark estimated decoherence times in the brain at (10^-13) to (10^-20) seconds, concluding that biological systems are effectively classical. The same reasoning applies (even more strongly) to meteorological systems, where temperature and particle interactions are vastly higher.

The question you need to ask is this: Given say MWI where you have all these different worlds splitting due to quantum events, how long does it take for classical differences to appear.

For the weather, this can take months.to be unrecognizably different. For a brick wall, probably decades. For a meteor hitting or missing Earth, probably millennia. For a human to choose one thing instead of another, maybe 10 minutes (a guess), and that depend on the gravity of the choice being made.

For the conception of a human, perhaps under a minute.

MWI is illustrative, but in any interpretation, specific quantum effects take about this long to cause or prevent these various macroscopic events.

Coherence is not in any way required for quantum events to have an effect. Quite the opposite. Absent a measurement (collapse?) of some sort, quantum events can have no effect..In short, quantum coherence does not persist long enough ...

Yes, but classical thermodynamics is a very chaotic system. Any difference, no matter how tiny, amplify into massive differences.in atmospheric systems to influence large-scale weather patterns. While every individual molecular collision is, in a sense, quantum, the statistical ensemble of billions of interactions behaves deterministically according to classical thermodynamics.

I agree that quantum improbability cannot be worked into weather prediction since there is no way to predict it, and weather prediction is done at significantly larger granularity, hardly a simulation at the atomic level. Hence it is good for a week or two at best. After that, you consult the farmer's almanac.

It is illuminating to track the weather prediction for a given day. It appears on my site 10 days hence. So save that prediction each day until the day in question arises. See how much the prediction changes as the day grows nearer. Sometimes it is fairly stable, but often it's all over the map, meaning they're practically guessing.

Sure, it exists, but decision making structures (both machine and biological) are designed to filter out the randomness out and leverage only deterministic processes. I mean, neither transistors nor neurons would function at all without quantum effects like tunneling, but both are designed to produce a repeatable classical effect, not a random one.Exactly. I said you were "ignoring" randomness, your wording is "denying". Same thing. Just so you know, randomness exists, human denials notwithstanding. — LuckyR -

ProtagoranSocratist

278Do you deny that a person can deliberate, procrastinate, or otherwise delay in decision making, such that the choice occurs over a period of time? — Metaphysician Undercover

ProtagoranSocratist

278Do you deny that a person can deliberate, procrastinate, or otherwise delay in decision making, such that the choice occurs over a period of time? — Metaphysician Undercover

No i never said that, what i'm trying to say is this:

"Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?"

It's fine and perfectly reasonable to say to yourself "i could have done _____ differently, for _____ reasons", but the phrasing of the question is "could anyone have made a different choice". We tell ourselves we should/could have made different choices as a narrative that will help us make different choices in the future, but the truth is the choice we made was already made.

There's an ancient phrase that "you can't step into the same river twice", and if you believe the validity of the phrase, then you will answer no to the question, but otherwise, you will answer yes. For me to answer "yes", it would imply that the "anyone" had different knowledge or at least knew they were about to do something wrong or imperfectly.

such that the choice occurs over a period of time? — Metaphysician Undercover

I had no idea a single choice could occur over a period of time. Could you elaborate on that? For example, what's the grey area between doing and not doing?

This is honestly one of the interesting things about "talking" on open internet forums: it always seems like a mistake because it's so open ended. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kIt's fine and perfectly reasonable to say to yourself "i could have done _____ differently, for _____ reasons", but the phrasing of the question is "could anyone have made a different choice". We tell ourselves we should/could have made different choices as a narrative that will help us make different choices in the future, but the truth is the choice we made was already made. — ProtagoranSocratist

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kIt's fine and perfectly reasonable to say to yourself "i could have done _____ differently, for _____ reasons", but the phrasing of the question is "could anyone have made a different choice". We tell ourselves we should/could have made different choices as a narrative that will help us make different choices in the future, but the truth is the choice we made was already made. — ProtagoranSocratist

I don't see the point. I agree, a choice made cannot be changed. But this does not negate the proposition that one could have made a different choice at the time when that choice was being made. This is just a feature of the nature of time. At the present, when time is passing we are free to make different choices. So when I look backward in time, I can say that "I could have made a different choice", meaning that at that time I was free to choose an alternative. It does not mean that it is possible that I actually made a choice other than I did. That, I believe, is a gross misunderstanding of the op, due to the ambiguity of "could have".

There's an ancient phrase that "you can't step into the same river twice", and if you believe the validity of the phrase, then you will answer no to the question, but otherwise, you will answer yes. For me to answer "yes", it would imply that the "anyone" had different knowledge or at least knew they were about to do something wrong or imperfectly. — ProtagoranSocratist

I think this is incorrect. I think you simply misunderstand the op's use of "could have", as explained above.

I had no idea a single choice could occur over a period of time. Could you elaborate on that? For example, what's the grey area between doing and not doing? — ProtagoranSocratist

How long does it take you to decide? Do you not deliberate? Take a simple math question for example, like 14x8-32+18, and time how long it takes you to decide what the answer is. Some choices take days, weeks, even years, to be decided. -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Take any choice you made in the past as an example. What were the reasons you made that choice? If given the same reasons would you have made a different choice? How and why?Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made? How would I know the answer to this question? — Truth Seeker

It seems to me that you only realize you could have made a different choice if you had access to different information, or reasons, than you did at the moment you made the choice. As such realizing you could have made a different choice always comes after the fact that you made the choice and now know the consequences and other possible choices that could have been made (more information), that was not available at the moment of decision.

So no, you could not have made a different choice because that would have meant that you had different information than you did when you made the decision. -

Athena

3.8kI'd love to hear your idea of conscience. — Copernicus

Athena

3.8kI'd love to hear your idea of conscience. — Copernicus

Well, do you know Jimmy Cricket?

Pinocchio was talked into going to a fun park instead of school, but the fun park turned into a place where children were turned into donkeys, and Pinocchio almost didn't escape.

Pinocchio was a wooden puppet, and a Blue Fairy turned him into a real boy and appointed Jimmy Cricket to help him make good decisions. A problem we have is not always knowing right from wrong. If we are lucky, we will have an uncomfortable feeling if we are considering doing something wrong, but often things are moving too fast, or we honestly believe we are doing the right thing, or we rationalize it isn't that bad, and we find out too late that it was the wrong and the consequences were that bad or worse, and then we get the uncomfortable feeling, and feelings of regret may follow. That uncomfortable feeling is like Jimmy Cricket trying to keep Pinocchio out of trouble.

Humans are pretty well programmed to be cooperative and moral, just as all social animals are programmed with social rules. But of course, things can go wrong, mostly because we don't know enough to know the right thing to do. Cicero said, “God's law is 'right reason.' When perfectly understood, it is called 'wisdom.' When applied by government in regulating human relations it is called 'justice.” Cicero

Today, we are very concerned about being smart, but unfortunately, we have neglected the need to develop wisdom. I think this cultural change leads to some serious problems, but at the same time, we have learned so many important things, and I hope this all balances out to a better future. -

LuckyR

740Sure, it exists, but decision making structures (both machine and biological) are designed to filter out the randomness out and leverage only deterministic processes. I mean, neither transistors nor neurons would function at all without quantum effects like tunneling, but both are designed to produce a repeatable classical effect, not a random one

LuckyR

740Sure, it exists, but decision making structures (both machine and biological) are designed to filter out the randomness out and leverage only deterministic processes. I mean, neither transistors nor neurons would function at all without quantum effects like tunneling, but both are designed to produce a repeatable classical effect, not a random one

Yes, that's their design. And when someone is contemplating an important decision, they bring all of that design to bear on the problem. How much of our decision making prowess do we bring to deciding which urinal to use in the public bathroom? Very, very little. What is taking the place of that unused neurological function? Habit perhaps or pattern matching. But what about a novel (no habit nor pattern) yet unimportant "choice"? It may not fulfill the statistical definition of the word "random", but in the absence of a repeatable, logical train of thought, it functionally resembles "randomness". -

ProtagoranSocratist

278I don't see the point. I agree, a choice made cannot be changed. But this does not negate the proposition that one could have made a different choice at the time when that choice was being made. This is just a feature of the nature of time. At the present, when time is passing we are free to make different choices. So when I look backward in time, I can say that "I could have made a different choice", meaning that at that time I was free to choose an alternative. It does not mean that it is possible that I actually made a choice other than I did. That, I believe, is a gross misunderstanding of the op, due to the ambiguity of "could have". — Metaphysician Undercover

ProtagoranSocratist

278I don't see the point. I agree, a choice made cannot be changed. But this does not negate the proposition that one could have made a different choice at the time when that choice was being made. This is just a feature of the nature of time. At the present, when time is passing we are free to make different choices. So when I look backward in time, I can say that "I could have made a different choice", meaning that at that time I was free to choose an alternative. It does not mean that it is possible that I actually made a choice other than I did. That, I believe, is a gross misunderstanding of the op, due to the ambiguity of "could have". — Metaphysician Undercover

That's fine, you can believe it's you or someone else could have done something differently, but it's just an opinion. For me, i think its really important to separate imaginary from real, hypothetical from not.

I think this is incorrect. I think you simply misunderstand the op's use of "could have", as explained above. — Metaphysician Undercover

No, im not misunderstanding anything. It's a very simple logical exercise. When someone misunderstands text, it's better to just explain what is being musunderstood if you have the better understanding.

But yes, i was wrong that "if you believe that quote, you will agree with me", but to me the trains of knowledge are consistent: if i can't step in the same river twice (as the river is always changing), then i also couldn't have done anything differently in the past...but if you reason "i have a local river called river calhoun, and i have stepped in it twice! Heraclitus was wrong!", then i can see why you would believe that you could have made different choices in the past.

Maybe it's the same river if there's no current, and it becomes a different one as the current starts, but as another user has said about the "could" question, whether you can step in the same river twice is a matter of perception. -

Truth Seeker

1.2kSo no, you could not have made a different choice because that would have meant that you had different information than you did when you made the decision. — Harry Hindu

Truth Seeker

1.2kSo no, you could not have made a different choice because that would have meant that you had different information than you did when you made the decision. — Harry Hindu

I agree. -

Truth Seeker

1.2kThank you for your thoughtful and technically well-informed reply. Let me address your key points one by one.

Truth Seeker

1.2kThank you for your thoughtful and technically well-informed reply. Let me address your key points one by one.

1. On Decoherence vs. Propagation of Quantum Effects

I agree that quantum coherence is not required for a quantum event to have macroscopic consequences. My point, however, is that once decoherence has occurred, the resulting branch (or outcome) behaves classically, and further amplification of that quantum difference depends on the sensitivity to initial conditions within the system in question.

So while a chaotic system like the atmosphere can indeed amplify microscopic differences, the relevant question is how often quantum noise actually changes initial conditions at scales that matter for macroscopic divergence. The overwhelming majority of microscopic variations wash out statistically - only in rare, non-averaging circumstances do they cascade upward. Hence, quantum randomness provides the ultimate floor of uncertainty, but not a practically observable driver of weather dynamics.

2. On the “Timescale of Divergence”

I appreciate your breakdown - minutes for human choice, months for weather, millennia for asteroid trajectories, etc. That seems broadly reasonable as an order-of-magnitude intuition under MWI or any interpretation that preserves causal continuity. What’s worth emphasizing, though, is that those divergence times describe when outcomes become empirically distinguishable, not when quantum indeterminacy begins influencing them. The influence starts at the quantum event; it’s just that the macroscopic consequences take time to manifest and become measurable.

3. On Determinism and Randomness in Complex Systems

I also agree that classical thermodynamics is chaotic, and that even an infinitesimal perturbation can, in principle, lead to vastly different outcomes. However, that doesn’t mean the macroscopic weather is “quantum random” in any meaningful sense - only that its deterministic equations are sensitive to initial data we can never measure with infinite precision. The randomness, therefore, is epistemic, not ontic — arising from limited knowledge rather than fundamental indeterminacy.

Quantum randomness sets the ultimate limit of predictability, but chaos is what magnifies that limit into practical unpredictability.

4. On Decision-Making Systems and Quantum Filtering

I completely agree that biological and technological systems are designed to suppress or filter quantum noise. The fact that transistors, neurons, and ion channels function reliably at all is testament to that design. Quantum tunneling, superposition, or entanglement may underlie the microphysics, but the emergent computation (neural or digital) operates in the classical regime. So while randomness exists, most functional systems are robustly deterministic within the energy and temperature ranges they inhabit.

* Decoherence kills coherence extremely fast in macroscopic environments.

* Chaotic systems can amplify any difference, including quantum ones, but not all microscopic noise scales up meaningfully.

* Macroscopic unpredictability is largely classical chaos, not ongoing quantum indeterminacy.

* Living and engineered systems filter quantum randomness to maintain stability and reproducibility.

So while I agree with you that quantum events can, in principle, propagate to the macro-scale through chaotic amplification, I maintain that in natural systems like the atmosphere, such amplification is statistically negligible in practice - the weather is unpredictable, but not “quantumly” so. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kBut yes, i was wrong that "if you believe that quote, you will agree with me", but to me the trains of knowledge are consistent: if i can't step in the same river twice (as the river is always changing), then i also couldn't have done anything differently in the past...but if you reason "i have a local river called river calhoun, and i have stepped in it twice! Heraclitus was wrong!", then i can see why you would believe that you could have made different choices in the past. — ProtagoranSocratist

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kBut yes, i was wrong that "if you believe that quote, you will agree with me", but to me the trains of knowledge are consistent: if i can't step in the same river twice (as the river is always changing), then i also couldn't have done anything differently in the past...but if you reason "i have a local river called river calhoun, and i have stepped in it twice! Heraclitus was wrong!", then i can see why you would believe that you could have made different choices in the past. — ProtagoranSocratist

I really don't see how your analogy about the two rivers is relevant. The question is, could the person, at the time prior to stepping into the river, have decided at that time, not to step into the river. I think that was a real possibility to the person at that time. Therefore at that time the person could have decided not to step into it. How do you think stepping into the same river twice is relevant? -

ProtagoranSocratist

278The question is, could the person, at the time prior to stepping into the river, have decided at that time, not to step into the river — Metaphysician Undercover

ProtagoranSocratist

278The question is, could the person, at the time prior to stepping into the river, have decided at that time, not to step into the river — Metaphysician Undercover

Stop trying to change the framing of OPs question: the question is "anyone". This kind of behavior is confusing. It's not a hypothetical scenario, because literally is possible in logic games and scenarios. Read the sleeping beauty thread if you don't agree.

I did my best to explain my logic. I will not repeat myself. -

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

With that I will agree. It's quite a different statement than the one at which I balked before.My point, however, is that once decoherence has occurred, the resulting branch (or outcome) behaves classically, and further amplification of that quantum difference depends on the sensitivity to initial conditions within the system in question. — Truth Seeker

How often? Ever time for a chaotic system. Takes time to diverge, but given a trillion decoherence events in a marble (not even in the atmosphere) in the space of a nanosecond, there's a lot more than a trillion worlds resulting from that, and the weather will be different in all of them, assuming (unreasonably) no further splits. I mean, eventually there's only so many different weather patterns and by chance some of then start looking like each other (does that qualify as strange attractors?). But the marble has a fair chance of still being a marble in almost all of those worlds.So while a chaotic system like the atmosphere can indeed amplify microscopic differences, the relevant question is how often quantum noise actually changes initial conditions at scales that matter for macroscopic divergence.

This is the part for which a reference would help. Clearly we still disagree on this point. The 'butterfly effect' specifically used weather as its example. Small changes matter. Not sometime, but all of them: any difference amplifies.The overwhelming majority of microscopic variations wash out statistically - only in rare, non-averaging circumstances do they cascade upward.

Well, first, to distinguish two outcomes, both must be observed by the same observer. That's not going to happen. Secondly, the butterfly can have an empirical effect immediately, but the <hurricane/hurricane elsewhere/not-hurricane> difference is what takes perhaps a couple months.2. On the “Timescale of Divergence”

...

What’s worth emphasizing, though, is that those divergence times describe when outcomes become empirically distinguishable

The deterministic equations (in a simulation say) are not to infinite detail and precision, so yes, quantum effects are ignored. The real equations are not deterministic since they are (theoretically) infinitely precise, and incomplete since quantum randomness cannot be part of the initial conditions. There are probably no initial conditions. Such a thing would require counterfactual definiteness, which is possible but not terribly likely.I also agree that classical thermodynamics is chaotic, and that even an infinitesimal perturbation can, in principle, lead to vastly different outcomes. However, that doesn’t mean the macroscopic weather is “quantum random” in any meaningful sense - only that its deterministic equations are sensitive to initial data we can never measure with infinite precision.

You don't know that. Yes, there are deterministic interpretations, but even given MWI (quite deterministic) and perfect knowledge, not even God can predict where the photon will hit the screen, and that's not even a chaotic effect.The randomness, therefore, is epistemic, not ontic — arising from limited knowledge rather than fundamental indeterminacy.

Which is why a computer typically runs the same code identically every time, given identical inputs. Ditto for a brain. Both work this way even given a non-deterministic interpretation of physics.I completely agree that biological and technological systems are designed to suppress or filter quantum noise.

Again, agree, which is why I suspect a human can be fully simulated using a classical simulation that ignores quantum effects, unless of course the human simulated happens to want to perform quantum experiments in his simulated lab.The fact that transistors, neurons, and ion channels function reliably at all is testament to that design. Quantum tunneling, superposition, or entanglement may underlie the microphysics, but the emergent computation (neural or digital) operates in the classical regime.

Sort of. Don't forget outside factors. My deterministic braIn might nevertheless decide to wear a coat or not depending on some quantum event months ago that made it cold or warm out today.So while randomness exists, most functional systems are robustly deterministic within the energy and temperature ranges they inhabit.

:up:* Decoherence kills coherence extremely fast in macroscopic environments.

* Chaotic systems can amplify any difference, including quantum ones, but not all microscopic noise scales up meaningfully.

* Macroscopic unpredictability is largely classical chaos, not ongoing quantum indeterminacy.

* Living and engineered systems filter quantum randomness to maintain stability and reproducibility.

Mind you, I agree that not all microscopic noise scales up meaningfully, but only because many systems (bricks for instance) are not all that chaotic at classical scales. The weather is not one of them, so I deny this below:

[/quote]I maintain that in natural systems like the atmosphere, such amplification is statistically negligible in practice[/quote]

neither transistors nor neurons would function at all without quantum effects like tunneling, but both are designed to produce a repeatable classical effect, not a random one — noAxioms

You make it sound so rational.Yes, that's their design. And when someone is contemplating an important decision, they bring all of that design to bear on the problem. — LuckyR

Take the 'should I cheat on my spouse' decision. I think chemistry, possibly more than rational logic, tends to influence such decisions. I wonder if robots currently can demonstrate that sort of internal conflict of interests.

What's that got to do with the what is effectively a free will/determinism debate? Free will is typically pitched as the rational side, with the chemicals often portrayed in the role of 'being compelled otherwise by physics'. Nonsense. Both are physics, and you're definitely responsible for your choice.

Agree, until you suggest that you are actually leveraging quantum randomness when doing something like urinal selection (which definitely has rules to it, and is thus a poor example), or rock-paper-scissors, where unpredictability (but not randomness) takes the day.How much of our decision making prowess do we bring to deciding which urinal to use in the public bathroom? Very, very little. What is taking the place of that unused neurological function? Habit perhaps or pattern matching. But what about a novel (no habit nor pattern) yet unimportant "choice"? It may not fulfill the statistical definition of the word "random", but in the absence of a repeatable, logical train of thought, it functionally resembles "randomness".

If I may butt in:

Good indication that you're talking past somebody. I also consider choice to be a process, not an event. From experimentation, it seems that it is essentially made before one becomes aware of the choice having been made, but even once made, one can change one's mind.I had no idea a single choice could occur over a period of time. — ProtagoranSocratist

I think that is more or less the question, but it is ill-phrased. I can answer either way.The question is, could the person, at the time prior to stepping into the river, have decided at that time, not to step into the river — Metaphysician Undercover

Classically, if the state (of all of you) immediately prior to the point (and not the process) of decision was the same, it means the process was already arriving at this conclusion. How could it not act on that process, regardless of where you consider that mechanism to take place? If you don't mean the state at that point, then when?

For instance, given two identical states hours (minutes, seconds?) before the decision, could the two states evolve differently? Yea, sure. My example above about choosing to wear a coat today leverages that sort of 'deciding otherwise'. But that's a case of, immediately before the decision, the environment being different, despite identical states some time prior.

All that seems utterly irrelevant to one being responsible for the decision. If you choose to skip the coat today and you get uncomfortably cold when you go out, who's fault do you think that is? Physics or you? Free will doesn't seem to have anything to do with it. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kClassically, if the state (of all of you) immediately prior to the point (and not the process) of decision was the same, it means the process was already arriving at this conclusion. How could it not act on that process, regardless of where you consider that mechanism to take place? If you don't mean the state at that point, then when? — noAxioms

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kClassically, if the state (of all of you) immediately prior to the point (and not the process) of decision was the same, it means the process was already arriving at this conclusion. How could it not act on that process, regardless of where you consider that mechanism to take place? If you don't mean the state at that point, then when? — noAxioms

I don't think we can accurately talk about real points within what is assumed to be a continuous process. This is the problem with representing the end of the decision making process as the "conclusion". "Conclusions" implies an end point. In reality, even as we are acting we are free to change our minds as the conditions require, so "conclusion" is arbitrarily assigned.

Therefore, to speak about a point immediately prior to the point of conclusion, really confuses the issue. When we remove those arbitrarily assumed "points", then we have a process which is in theory infinitely divisible. Then at any time in that duration the process could theoretically be changed. Even between your two arbitrary points, A being immediately prior to B, being the point of decision, there must be a duration of time during which a change in the process could occur between the arbitrarily assumed A and B.

The further problem however, would be the mechanism of such a change. Since I've already outlawed points, to get to this position, I cannot now say that the change happens at a point in between the two. This leaves a problem. -

ProtagoranSocratist

278I also consider choice to be a process, not an event. — noAxioms

ProtagoranSocratist

278I also consider choice to be a process, not an event. — noAxioms

It can be either one: i can think about how i want to murder someone (technically, part of the choice, in the "choice is process" logic). If i decide it's the right decision, then the choice is made, and then i would start answering the question of how. I can change my mind still during this process, saying to myself "no, it's a bad idea to do this", i made a second choice, putting an end to my "how" process. Either way, i made two choices. -

Truth Seeker

1.2k

Truth Seeker

1.2k

1. On Decoherence and Chaotic Amplification

I appreciate your clarification. I agree that once decoherence has occurred, each branch behaves classically. My emphasis was never that quantum events never cascade upward, but that most do not in practice. Chaotic sensitivity doesn’t guarantee amplification of all microscopic noise; it only ensures that some minute differences can diverge over time. The key is statistical significance, not logical possibility.

The fact that there are trillions of decoherence events per nanosecond doesn’t entail that every one creates a macroscopically distinct weather trajectory. Many microscopic perturbations occur below the system’s Lyapunov horizon and are absorbed by dissipative averaging. The “butterfly effect” metaphor was intended to illustrate sensitivity, not to claim that every quantum fluctuation alters the weather.

So:

Yes, chaos implies amplification of some differences.

No, it doesn’t imply that quantum noise routinely dominates macroscopic evolution.

Empirically, ensemble models of the atmosphere converge statistically even when perturbed at Planck-scale levels, suggesting the mean state is robust, though individual trajectories differ. (See Lorenz 1969; Palmer 2015.)

2. On Determinism, Ontic vs. Epistemic Randomness

You’re right that we can’t know that randomness is purely epistemic. My point is pragmatic: there’s no experimental evidence that ontic indeterminacy penetrates to the macroscopic domain in any controllable way.

MWI, Bohmian mechanics, and objective-collapse theories all make the same statistical predictions. So whether randomness is ontic or epistemic is metaphysical until we have a test that distinguishes them.

Even if indeterminacy is ontic, our weather forecasts, computer simulations, and neural computations behave classically because decoherence has rendered the underlying quantum superpositions unobservable.

So I’d phrase it this way:

The world might be ontically indeterministic, but macroscopic unpredictability is functionally classical.

3. On Functional Robustness

Completely agree: both transistors and neurons rely on quantum effects yet yield stable classical outputs. The entire architecture of computation, biological or digital, exists precisely because thermal noise, tunnelling, and decoherence are averaged out or counterbalanced.

That’s why we can meaningfully say “the brain implements a computation” without appealing to hidden quantum randomness. Penrose-style arguments for quantum consciousness have not found empirical support.

4. On Choice, Process, and Responsibility

I share your intuition that a “choice” unfolds over time, not as a single instant.

Libet-type studies show neural precursors before conscious awareness, yet subsequent vetoes demonstrate ongoing integration rather than fatalistic pre-commitment.

Determinism doesn’t nullify responsibility. The self is part of the causal web. “Physics made me do it” is no more an excuse than “my character made me do it.” In either case, the agent and the cause coincide.

Thus, even in a deterministic universe, moral responsibility is preserved as long as actions flow from the agent’s own motivations and reasoning processes rather than external coercion.

5. Summary

Decoherence → classicality; not all micro noise scales up.

Chaos → sensitivity; not universality of amplification.

Randomness → possibly ontic, but operationally epistemic.

Functional systems → quantum-grounded but classically robust.

Agency → compatible with determinism when causation runs through the agent.

Quantum indeterminacy might underlie reality, but classical chaos and cognitive computation sit comfortably atop it.

Responsibility remains a structural property of agency, not an escape hatch from physics. -

LuckyR

740Agree, until you suggest that you are actually leveraging quantum randomness when doing something like urinal selection (which definitely has rules to it, and is thus a poor example), or rock-paper-scissors, where unpredictability (but not randomness) takes the day.

LuckyR

740Agree, until you suggest that you are actually leveraging quantum randomness when doing something like urinal selection (which definitely has rules to it, and is thus a poor example), or rock-paper-scissors, where unpredictability (but not randomness) takes the day.

I concede that the term "randomness" in the context of this conversation is not true statistical Randomness, rather a placeholder term to describe the absence of a logical train of thought as pertains to decision making, pondering, if you will. Thus I'll take your "agree"ment and call it a day.

We can cut to the chase, everyone agrees that humans ponder decisions, weigh the pros and cons of possible choices. What folks disagree on is whether this pondering is a functional illusion, such that I was always going to select chocolate, never vanilla, regardless of going through the act of pondering my "choice". In this scenario one can never go back and make a different "choice", because the concept of "choice" was an illusion. It was always going to be chocolate. Most, however believe that pondering is functionally real and thus yes, they could have selected vanilla. There is no Real World way to prove it one way or another and the answer similarly has no Real World implication since it can only be demonstrated theoretically, never in reality. But I find it more psychologically coherent to believe what I perceive, then to assume my experience is an (unprovable) illusion. -

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

The mathematics says otherwise. Any quantum decoherence event, say the decay of some nucleus in a brick somewhere, will have an effect on Mars possibly within 10 minutes, and will cause a completely different weather pattern on Mars withing months. The brick on the other hand (after even a second) will have all its atoms having different individual momentums, but the classical brick will still be mostly unchanged after a year. This is a logical necessity for any quantum event. If it has no such cascading effect, then it didn't actually happen, by any non-counterfactual definition of 'happened'.1. On Decoherence and Chaotic Amplification

I appreciate your clarification. I agree that once decoherence has occurred, each branch behaves classically. My emphasis was never that quantum events never cascade upward, but that most do not in practice. Chaotic sensitivity doesn’t guarantee amplification of all microscopic noise; it only ensures that some minute differences can diverge over time. — Truth Seeker

If it doesn't, then the event probably took place outside our event horizon, which is currently about 16 GLY away, not far beyond the Hubble sphere.The fact that there are trillions of decoherence events per nanosecond doesn’t entail that every one creates a macroscopically distinct weather trajectory.

Sure, almost all perturbations occur below a system's Lyapunov horizon, which just means that more time is needed (couple days in the case of weather) for chaotic differences to become classically distinct.Many microscopic perturbations occur below the system’s Lyapunov horizon and are absorbed by dissipative averaging.

Depends on your definition of 'dominates'. Yes, the state of a chaotic system is a function of every input, no matter how trivial. Yes, they all average out and statistically the weather is more or less the same each year, cold in winter, etc. But the actual state of the weather at a given moment is not classically determined. There is no event that doesn't matter.No, it doesn’t imply that quantum noise routinely dominates macroscopic evolution

Coin flips are a lot like the weather. Take trillions of coins, black & white on opposite sides, and throw them on ground and look at it from an airplane. It looks gray every time, no matter how many tries you attempt. But up close, each toss is distinct, and if those distinctions amplify in a chaotic manner, different patterns will form with each toss, and those classical patterns will very much be visible for the airplane.

I was hoping for Conway's Game of Life to drive the chaos, but that game is actually not very chaotic, and the resulting patterns probably would just look mostly white from a distance with no distinct structures emerging like hurricanes.

Perturbations in ensemble models are far larger than Planck level. Yes, hurricanes, once formed, tend to be somewhat predictable for 8-10 days out. The perturbations are effectively running the model multiple times with minor differences, generating a series of diverging predictions. You average out those predictions to get a most probable path. Run those difference out to 3 weeks and major divergence will result.Empirically, ensemble models of the atmosphere converge statistically even when perturbed at Planck-scale levels

Quantum theory (not any of its interpretations even) does not allow any indeterminacy to be controlled. The mathematical model from the theory also disallows any information to be gathered from the randomness. If it were otherwise, the theory would be falsified.My point is pragmatic: there’s no experimental evidence that ontic indeterminacy penetrates to the macroscopic domain in any controllable way.

I hate to be a bother, but there is no collapse at all under MWI, and DBB is phenomenological collapse only, not ontic. This is a set of objective collapse interpretations posited separately by Ghirardi, Weber, Penrose.MWI, Bohmian mechanics, and objective-collapse theories

The interpretations you list are deterministic. Most others are not. Under MWI, you could have, and actually did, choose otherwise (but was that you?). Under DBB, you could not have chosen otherwise.

Every interpretation makes the same statistical predictions. Superdeterminism doesn't, but it's not a valid interpretation of QM, just an alternate interpretation of the physics... all make the same statistical predictions.

Still, I agree with your point 2. It doesn't matter whether randomness is ontic or epistemic. There will never be a test for that.

I agree with this, but remember that brains and computers are not closed systems, and the inputs might be subject to chaotic effects. It is the instability of those inputs that mostly accounts for a person 'having done otherwise' in two diverging worlds.3. On Functional Robustness

Completely agree: both transistors and neurons rely on quantum effects yet yield stable classical outputs. The entire architecture of computation, biological or digital, exists precisely because thermal noise, tunnelling, and decoherence are averaged out or counterbalanced.

That’s why we can meaningfully say “the brain implements a computation” without appealing to hidden quantum randomness.

See 'insanity defense', which is effectively the latter. Still responsible, but different kind of jail.“Physics made me do it” is no more an excuse than “my character made me do it.”

Anyway, we also seem to agree on point 4.

The pondering is not an illusion. With the possible exception of epiphenomenalism, the pondering takes place, and the decision is the result of that. Given DBB style determinism, your decision to select chocolate was set at the big bang. Not true under almost any other interpretation, but under all of them (any scientific interpretation), the chocolate decision was a function of state just prior to the pondering, which does not mean it wasn't your decision.What folks disagree on is whether this pondering is a functional illusion, such that I was always going to select chocolate, never vanilla, regardless of going through the act of pondering my "choice". — LuckyR

Under non-QM philosophies, there's more going on than what science knows about, and all bets are off. How this makes you more responsible has never been justified to my satisfaction, but if an entity external to the universe is what's choosing chocolate, then that entity (and not the body it controls) is what's responsible to another entity also not part of the universe.

Of all that, the first paragraph is a monist take. The dualists are the ones that suggest that one is not responsible (to whom?) for their actions if the actions are due to a view with which they don't agree. All very straw man.

That's a total crock. It being a choice has nothing to do with it being deterministic or not, since choice is the mechanism by which multiple options are narrowed down to one. Your assertion makes the classical mistake of conflating a sound mechanism for selecting from multiple options, with being compelled against one's will to select otherwise, the latter of which actually does make it not a real choice, and thus takes away (not gives) responsibility.In this [deterministic] scenario one can never go back and make a different "choice", because the concept of "choice" was an illusion.

In the end, one cannot make two choices. One cannot have chosen vanilla if chocolate was chosen, true in deterministic, random, and compelled scenarios.

Any choice making mechanism requires as much deterministic processes as possible, minimizing the randomness which is the alternative.

3rd alternative: let somebody else choose for you, which seems to make not you responsible, but rather the other person. Imagine crossing the street this way. You close your eyes and go when somebody else says to. If you get hit, it's his fault, but you still are the one enduring the consequences.

Agree. Also don't think the process of making a choice has an end point, like all pondering has ceased and all that's left is to implement the choice (say "chocolate please" to the ice cream guy). Cute idealized description, but that's not how it works.I don't think we can accurately talk about real points within what is assumed to be a continuous process. — Metaphysician Undercover

You seem to agree, balking that 'conclusion' implies an end point.

Ah, now we get into adjacent points and Zeno and that whole rat hole. Agree, we avoid that path.Therefore, to speak about a point immediately prior to the point of conclusion

What's the problem then? Change happens over time. Where's the problem? I made no mention of points in that.Since I've already outlawed points, to get to this position, I cannot now say that the change happens at a point in between the two. This leaves a problem.

What happened to decisions and the eventual state of no longer being able to have chosen otherwise?

What I got from this is that choices can be broken down into sub-choices, and conversely combined into larger choices.It can be either one: i can think about how i want to murder someone (technically, part of the choice, in the "choice is process" logic). If i decide it's the right decision, then the choice is made, and then i would start answering the question of how. I can change my mind still during this process, saying to myself "no, it's a bad idea to do this", i made a second choice, putting an end to my "how" process. Either way, i made two choices. — ProtagoranSocratist

Of course the steps need not be thus ordered. I have pondered 'how to murder' far more often than any actual decision to go and do it, not counting all the bug smitings and mammal murders.

Took out my first Opossum just a couple weeks ago. It wasn't a conscious choice to do so.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum