-

Streetlight

9.1kSo that is an important new development arising out of neoliberal thinking - the financialisation of national balance sheets.

Streetlight

9.1kSo that is an important new development arising out of neoliberal thinking - the financialisation of national balance sheets.

But it seems way distance from any biopolitics or bodily precariousness. You haven't actually drawn a connection I can see.

...I agree that neoliberalism is about turning everything that composes life into a tradable commodity. — apokrisis

But the argument is not so much that life itself becomes a commodity but that it has been co-opted into circuits of speculative finance. It's the form of commodification that matters - in this case a matter of financialization and not 'merely' commodification. The key distinction is that of temporal orientation: unlike a commodity, the value of a patented cell line (for example) is not so much it's exchange value - what it can be bought and sold for according to the law of supply and demand - but the promise it holds for future innovation. Life itself attracts finance and becomes generative of surplus by it's mere fact of existence. And while life becomes financialized, what is commodified is not life, but it's promise. What is traded are promises.

The crux of it is that this is exactly the same commodity form as debt. Debt too is now available for financialization in the form of the promise, and in both cases, the promise is self-generative of surplus. Here's Cooper: "What comes to light here is the violence of the debt form and the flipside of the promise—if it is to actualize at all, capital's future embryoid body will need to draw on a continuous "gifting" of reproductive labor and tissues. In this way capital's dream of promissory self-regeneration finds its counterpart in a form of directly embodied debt peonage.... Wealth creation in the pure debt form—the regeneration of money from money and life from life, without final redemption."

In other words this cooption of life into the circuits of speculative finance converges with debt as the high-point of capitalist accumulation - a fantasy realized of money and life that generates more money, indefinitely, by, again, the sheer fact of their existence. The Marxist point - which I only mentioned really more as an aside - is that this fantasy is just that, a fantasy insofar as this self-generativity is bound to encounter limits of the real, whence the GFC - in which the pure promise of the debt form was no longer sustainable re: 'toxic' mortgages in the US housing market - or the popping of the biotech bubble which happened last year (when investors finally gave up waiting on the unrealized promises of patented cell lines and so on).

(The perfect coincidence of life and debt surplus is probably nowhere better exhibited than in the destruction of the centuries old Iraqi agricultural sector: after the toppling of Saddam and the destruction of the Iraqi seed bank, Iraqi farmers were prohibited from using any other seed than Monsanto's particular patented GM ones, which, because of other orders that further made it impossible for them to recycle seeds, meant they had to buy new seed each crop cycle (further, they could only use Monsanto patented herbicides, which kill all other crops than Monsanto's own). And of course, the seed purchases where financed by generous loan offers placing the farmers into a situation of more or less forced indebtedness: the loans could only be used for Monsanto's seed, which basically locked them in. The result, in Wendy Brown's words, were that: "Organic, diversified, low-cost, ecologically sustainable wheat production in Iraq is finished." See the account in Brown, Undoing the Demos).

But even this is not what I'm super concerned with. My real interest lies in the collapse of temporal categories occasioned by such developments: by tethering calculations of risk in the present to the quite literally incalculable speculative promises/fears of the future, almost every and any 'preventative' action is licenced. Essentially what is at stake is a temporal 'state of exception' in which the boundaries between the calculable and the incalculable are effaced such that there is cartre blanche to do anything whatsoever in the name of the incalculable. Hence the widespread 'need' to enact legislation - all around the Western world - that violates fundamental rights in order to protect us from Godknowswhat impending, immanent, but incalculable risk of.... ???. A kind of permanent state of emergency, licenced by temporal collapse. The ubiquitous threat of 'terrorism', unsurprisingly finds a perfectly receptive audience in neoliberal societies.

One consequence of this is that society can no longer be made to bear the costs of well, anything: "Contrary to the philosophy of the social state, [neoliberalism] teaches that the collective risks gathered under the banner of the nation can no longer be (profitably) collectivized, normalized, or insured against. Henceforth, risk will have to be individualized while social mediations of all kinds will disappear" (Cooper) - note that this rounds out what you say about the valorizaion of individual self-actualization against society. What I'm interested in, again, is the mechanisms that underlie this shift. So while I agree with you that of course neoliberalism militates against society and the romanticzes of the individual, this is so obvious a point that it's been made by every critic of neoliberalism since basically time immemorial. But these myths don't just spring up out of nowhere - the point is the chart the mechanisms that have brought it into being, and have allowed it to catch on. -

apokrisis

7.8kIn plain language, where is the promised account of how any of this impacts on the individual's relation to their own body?

apokrisis

7.8kIn plain language, where is the promised account of how any of this impacts on the individual's relation to their own body?

How doesn't the biotech bubble impact in a way that makes me feel precarious about myself. Ditto GM crops? Ditto the financial games played on third world farmers?

If this wasn't written in such tortured prose, it would be clear that it is nothing more than a list of concerns with no logical connection.

Fostering a sense of crisis to be able to push through a political agenda is quite the opposite of creating the false market optimism on which speculative bubbles depend. That is just one example of how none of the dots connect here.

So sure, biotech is another bubble asset. But that isn't a "debt" issue.

The GFC was about turning debt into a tradable asset class. The claim was risk could be packaged to create financial instruments that performed like good old unexciting bonds (plus a percent). Biotech is a risky stock, an upfront gamble. You might be buying a future promise, but a naked risk one, not a financialised one that claims to remove the uncertainty in the return.

To confuse the two is financial illiteracy.

I think you need better examples of how biology is being financialised rather than just commodified. And then any actual example of that making folk feel a bodily precariousness of some personal form. -

Streetlight

9.1kFostering a sense of crisis to be able to push through a political agenda is quite the opposite of creating the false market optimism on which speculative bubbles depend. — apokrisis

Streetlight

9.1kFostering a sense of crisis to be able to push through a political agenda is quite the opposite of creating the false market optimism on which speculative bubbles depend. — apokrisis

Except at no point did I suggest anything about 'fostering a sense of crisis'. So just one example of how you're a bit slow on the dot connecting front to begin with.

Anyway, as usual you're singularly incapable of holding a discussion without turning it into some sort of dick measuring competition. I almost forgot why you're an awful person to discuss anything with. Thanks for the provocations anyway I guess. -

apokrisis

7.8kHence the widespread 'need' to enact legislation - all around the Western world - that violates fundamental rights in order to protect us from Godknowswhat impending, immanent, but incalculable risk of.... ???. A kind of permanent state of emergency, licenced by temporal collapse. The ubiquitous threat of 'terrorism', unsurprisingly finds a perfectly receptive audience in neoliberal societies. — StreetlightX

apokrisis

7.8kHence the widespread 'need' to enact legislation - all around the Western world - that violates fundamental rights in order to protect us from Godknowswhat impending, immanent, but incalculable risk of.... ???. A kind of permanent state of emergency, licenced by temporal collapse. The ubiquitous threat of 'terrorism', unsurprisingly finds a perfectly receptive audience in neoliberal societies. — StreetlightX

So at no point did you suggest anything about the fostering of a sense of crisis? Hmm.

Anyway, as usual you're singularly incapable of holding a discussion without turning it into some sort of dick measuring competition — StreetlightX

Perhaps if you posted a coherent argument it would go better for you. Have a go at writing out your OP in plain language without all the fancy words. And with proper examples to support your point at each turn. See how much sense you think it makes then. -

Streetlight

9.1kSo at no point did you suggest anything about the fostering of a sense of crisis? Hmm. — apokrisis

Streetlight

9.1kSo at no point did you suggest anything about the fostering of a sense of crisis? Hmm. — apokrisis

Yep, I wrote that in a paragraph about the changing temporal relations of risk, and how that legitimises legislation like that. But sure, yeah, read the word that doesn't appear it in once into it. And then complain I'm using big words. What a joke.

Perhaps if you posted a coherent argument it would go better for you. Have a go at writing out your OP in plain language without all the fancy words. And with proper examples to support your point at each turn. See how much sense you think it makes then. — apokrisis

Big scary words hurt po po? Streetlight type slow for po po now? Don't scared okay po po? -

Shawn

13.5k

Shawn

13.5k

This is wrong on so many accounts. It doesn't mention the fact that there are automatic stabilizer built into the economy that prevents excessive debt from happening. Such as inflation. But, so what; that's a dream when you're in debt.

Furthermore, debt does not equal economic fallibility. For example, it took a lot of debt to make the Manhattan Project happen; but, then look at the results of that investment. Similarly, the technological revolution was largely made possible by military elements originating from the government (DARPA, etc.), a la Keynesian economics (which seems to be criticised and ridiculed here). Obviously, the military doesn't have a media outlet of their own; but, it doesn't take a genius to realize how much that America has produced from investigations and analysis done by the military. -

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k

@'StreetlightX'

the categories that once used to exempt the body from it's circuits now begin to capture it: beyond the much mentioned 'commodification' of the body (in terms of say, stem cells, DNA sequences, and other, now 'patentable' biological 'innovations'), you also get - as again charted by Cooper - the militarization of biology, where the body itself becomes a site of security concern -

Beyond commodification and warfare, one can imagine other places in which categories once applicable to non-humans gradually shade into human considerations - I have in mind Agamben's other studies on the growing indistinction between animal and human, law and life, the sacred and the profane, etc.

So again, while it's true that this represents a culmination of long-term trends, what's changed is the specificity of that movement which has now increasingly encircled even the body, which at least at one point could be left out of it. In Marxist parlance, capital has set it's sights not only on the means of production, but on the means of (biological) reproduction as well. This change needs also to be tracked in tandem with the temporal shift in which capital, generalizing the debt form, now beings to place more and more importance on not just the mode of production, but on the speculative mode of prediction which underlies it's upheaval of temporal categories as well (cf. the work of Ivan Ascher on the 'portfolio society' which we now inhabit). But this last is a larger point that needs elaboration.

I read this and the developments in the thread a few times, there's something I'd quite like to highlight with regard to the generalisation of the debt form, in particular sketching a way how 'categories once applicable to non-humans gradually shade into human considerations' in this manner from a roughly Marxist perspective - or one way this may've happened at least.

Speculative ability has always been a feature of the expansion of accumulation, in particular businesses expand typically through a loan in their initial stages. Attaining such a thing is classically based on estimates of the profitability of the businesses' endeavours. In essence, this is taking labour and attaching an exchange value to it in the future. Implicit in this is the quantification and operationalisation (numerical representation) of the accumulation of capital itself. I think the way you usually denote this procedure is intensification. This description raises the question: how do we get from the intensification of a business' future to the intensification of the individual? This is an essentially historical question, but I would like to say that a reasonable amount of the blame can be stuck on health insurance.

Health insurance in its earliest form (in America) popped up during the Great Depression in America. [An aside: maybe this is a historical predecessor of precarity] This was typically to ensure that if an individual suffered an accident, then they would be compensated. If you attempt to do a profit maximisation on this, it encourages speculative activity from insurance and an evaluation of how likely and how soon an individual is to receive a payment from it. This would then not just be a quantification of an individual's current health, but on their future health prospects - conceiving of the individual as a risk profile to be hedged and managed. If an individual is deemed an acceptable risk (+expected money) then their money will be used in speculation to get more money. Thus the individual's body is intensified through their predicted value.

It would then be a question of how the intensification of the body spread to the level of ideology rather than as part of business practice. I imagine the growth of group awareness of experimental science, and the development of quantitative rather than qualitative methods in those fields (especially medicine) would play a role. -

apokrisis

7.8kYou are simply highlighting how your abstracted jargon conceals from even yourself the huge logical gaps you are leaving in the wake of your purple prose and frantic cut and paste.

apokrisis

7.8kYou are simply highlighting how your abstracted jargon conceals from even yourself the huge logical gaps you are leaving in the wake of your purple prose and frantic cut and paste.

For instance here, if you weren't suggesting the deliberate fostering of a sense of crisis, then why would tying current investments to future returns be automatically a bad thing? Especially when the argument you want to make is that it is merely a vague or indistinct thing.

As I point out, the biotech bubble would be the product of investor optimism. It has nothing to do with debt economics or financialised balance sheets as such. So why - even inadvertently - would it create some dramatic sense of precariousness?

If you tried to write out your clever musings in plain language, they would just fall apart as there is nothing substantive by way of logical links to hold them together. Sorry if it upsets you to have it pointed out. -

Streetlight

9.1kExcept the GFC was caused precisely by investment into assets that were not revenue generating (housing), and speculative finance - derivative trading on futures and so on - is almost entirely unproductive. And given that private debt stands currently at 156% of US GDP - 17% less than it's height during the GFC (and triple what it was in 1950) and growing - you'd have to be completely blind to economic reality to think the 'stabilizers' you speak of are in anyway working.

Streetlight

9.1kExcept the GFC was caused precisely by investment into assets that were not revenue generating (housing), and speculative finance - derivative trading on futures and so on - is almost entirely unproductive. And given that private debt stands currently at 156% of US GDP - 17% less than it's height during the GFC (and triple what it was in 1950) and growing - you'd have to be completely blind to economic reality to think the 'stabilizers' you speak of are in anyway working. -

Shawn

13.5kI agree that neoliberalism is about turning everything that composes life into a tradable commodity. That sounds a good idea, but then always results in an opaque and weakly regulated system that is easy to game. So that is a huge source of psychic instability. It erodes personal or community level control. The economy becomes as impersonal and capricious as the weather. We become helpless in its tides. — apokrisis

Shawn

13.5kI agree that neoliberalism is about turning everything that composes life into a tradable commodity. That sounds a good idea, but then always results in an opaque and weakly regulated system that is easy to game. So that is a huge source of psychic instability. It erodes personal or community level control. The economy becomes as impersonal and capricious as the weather. We become helpless in its tides. — apokrisis

Yes, but one of the foundations upon which the USA is a vigilant and informed public. That the Republicans keep the population vigilant with invisible enemies from within and outside the borders, then that's a political issue, not an economic one. -

Shawn

13.5kExept the GFC was caused precisely by investment into assests that were not revenue generating (housing), and speculative finance - derivitive trading on futures and so on - is almost entirely unproductive. And given that private debt stands currently at 156% of US GDP - 17% less than it's hight during the GFC and growing - you'd have to be completely blind to economic reality to think the 'stabilizers' you speak of are in anyway working. — StreetlightX

Shawn

13.5kExept the GFC was caused precisely by investment into assests that were not revenue generating (housing), and speculative finance - derivitive trading on futures and so on - is almost entirely unproductive. And given that private debt stands currently at 156% of US GDP - 17% less than it's hight during the GFC and growing - you'd have to be completely blind to economic reality to think the 'stabilizers' you speak of are in anyway working. — StreetlightX

So, why didn't QE lead to much higher inflation rates? Or more simply, why is inflation so low in the US? Because most of the money is invested or held in offshore havens. If that money entered the money stream in terms of investments and loans, then what would that result in? Revenue and growth, I suppose. -

Streetlight

9.1kYou are simply highlighting how your abstracted jargon conceals... — apokrisis

Streetlight

9.1kYou are simply highlighting how your abstracted jargon conceals... — apokrisis

When Mr. Apo - "symmetry" "constraint" "triadic" - Krisis accuses you of jargon mongering. You couldn't make this up if you tried. -

Pneumenon

480My initial response to this is to step back and say that humans have not learned to control their technology yet. As with the economy, I apprehend a marked tendency in contemporary discourse to see technological trends almost as forces of nature rather than the results of the actions of individual humans.

Pneumenon

480My initial response to this is to step back and say that humans have not learned to control their technology yet. As with the economy, I apprehend a marked tendency in contemporary discourse to see technological trends almost as forces of nature rather than the results of the actions of individual humans.

Such forces can be manipulated, worked with, though perhaps not controlled. The problem is that our standard means of understanding and working with things are the result of a culture that takes natural science as paradigmatic for, uh, pretty much everything. Thing is, you can't render things like market forces or technological change intelligible using methods analogous to the study of chemical reactions or whatever. Or if you can, you can only do so using very, very loose analogies, to the point where it becomes more art than science.

I don't think that the answer is a post-capitalist society, per Zizek's haunting aphorism that it's easier to imagine the apocalypse than the end of capitalism. At least, that's not a workable next step, or even end goal, given that it's not even visible at this point.

In the end, I have to question whether a strictly economic analysis is appropriate here. I understand that this is all very political, of course, but so much of it is enabled/dictated by technological change that I don't think we can analyze it like Marxist historians looking for contradictions in the system or some such. You need to bring in a wider conceptual context to get out of your "mapping" phase, methinks. -

apokrisis

7.8kWhen Mr. Apo - "symmetry" "constraint" "triadic" - Krisis accuses you of jargon mongering. You couldn't make this up if you tried. — StreetlightX

apokrisis

7.8kWhen Mr. Apo - "symmetry" "constraint" "triadic" - Krisis accuses you of jargon mongering. You couldn't make this up if you tried. — StreetlightX

It is not the individual words so much - although plenty of them are way more obscure than talk of symmetry or constraints. It is the dense thickets of abstractions with no pauses for illustrative supporting examples.

And on top of that, the overall hesitant tone where a concern is introduced in one paragraph, only for us to be told that wasn't really it, here is the new real concern. Your posts unfold as a series of self-corrections arriving at no resolved point. Clearly you want to make some thread of an idea come out right, but all you can do is point off in a variety of directions as you meander in a maze of PoMo mutterings.

You see my problem:

But the argument is not so much that life itself becomes a commodity but that it has been co-opted into circuits of speculative finance. — StreetlightX

The key distinction is that of temporal orientation: — StreetlightX

The crux of it is that this is exactly the same commodity form as debt. — StreetlightX

In other words this cooption of life into the circuits of speculative finance converges with debt as the high-point of capitalist accumulation — StreetlightX

But even this is not what I'm super concerned with. My real interest lies in the collapse of temporal categories occasioned by such developments: by tethering calculations of risk in the present to the quite literally incalculable speculative promises/fears of the future, almost every and any 'preventative' action is licenced. — StreetlightX

Essentially what is at stake is a temporal 'state of exception' in which the boundaries between the calculable and the incalculable are effaced such that there is cartre blanche to do anything whatsoever in the name of the incalculable. — StreetlightX

these myths don't just spring up out of nowhere - the point is the chart the mechanisms that have brought it into being, and have allowed it to catch on. — StreetlightX

In this tangle of words, what you seem to be trying to argue is that there is this thing called speculative finance. And "human biology" is being sucked into its voracious maw as another asset to be monetised. Neoliberalism is a mechanism that allows every aspect of life to made tradable - and thus to be traded away in a fashion that inevitably favours the few, disadvantages the many, even though the political promise is that a free market floats all boats.

So on neoliberalism and why it is a danger, I'm sure we agree. It is a routine analysis as you say.

And on making human biology a tradable asset, well yes I guess so if you mean medical biotechnology and gene engineering. But I asked how does that add a specific form or precariousness to our individual lives (as you seemed to be suggesting in your tortured prose)?

Why would ordinary folk find that an existential threat? Instead, surely new medicines are a bright promise. Start-up companies generally excite the imagination. A generalised use of biological information has no obvious personal implications.

So in regards to the Precariat - the modern world of uncertain employment - you have made no logical connection here.

Then working back to your notion of speculative finance, this looks to conflate blind risk taking and complex risk-removing behaviour.

As you also acknowledge, financial instruments like derivatives are designed simply to amplify economic actions. So they can work in both directions. They can allow economic actors to take bigger leveraged risks. Or they can be used to insure a future outcome against risk.

Of course again there are the large and now painfully obvious shortcomings of permitting financial complexity. It creates a system that is easy to game - especially if you get the politicians to take away the market regulators.

So the economic system in theory might aim to be just - neoliberalism is not intrinsically malign as your argument appears to demand - but the Wall St elite got the safeguards removed so they could screw over nations of home buyers and even whole small nations like Greece and Iceland.

So when it comes to "speculative finance", this becomes just a pejorative term in your hands - a way to win the argument without clearly making one. It is easy to read your uncertainty in applying it. Sometimes you are talking about malign neoliberalism, sometimes about an elite of individual economic actors. Sometimes you are talking about risk-avoidance that went wrong (like CDOs), sometimes about speculative asset bubbles - overly-optimistic risk taking.

You seem aware of the variety of economic and political issues you are trying to shoehorn into a single bogeyman term - speculative finance - but when called on it, you get pissy rather than attempting to mount some further justification or clarification.

So these things need tying together properly:

1) speculative finance as one unitary force.

2) human biology as a new tradable asset class.

3) neoliberalism being inherently a social evil rather than simply a neutral mechanism.

4) the above adding up to an actual source of existential precariousness in the Precariat. -

Shawn

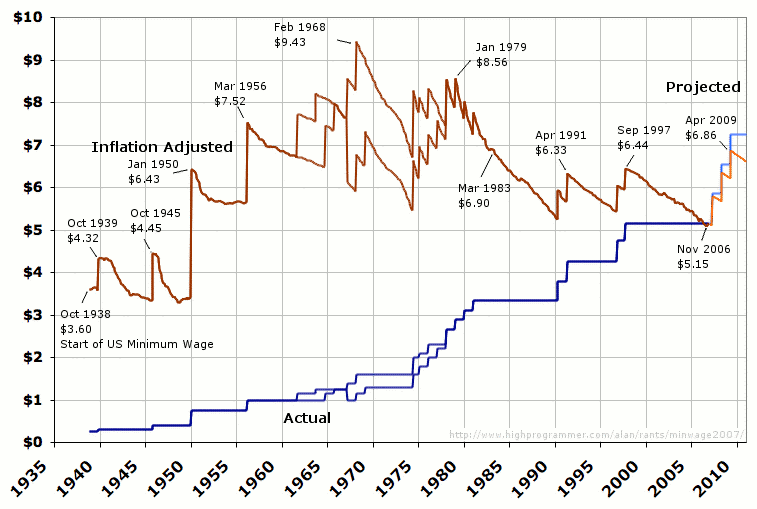

13.5kThere's also a reason why wages have stagnated. Due to a multitude of factors. Companies exporting jobs overseas, hiring cheaper labor to come to the US to work in high-tech jobs, the deflationary tendency technology has on purchasing power or most goods, lower oil prices in general, quite low inflation that would normally lead to pressure on wages and prices to rise, higher productivity with fewer hours (part-time vs full-time employment, which is more economical for a company to hire part-time if the job can be done in fewer hours).

Shawn

13.5kThere's also a reason why wages have stagnated. Due to a multitude of factors. Companies exporting jobs overseas, hiring cheaper labor to come to the US to work in high-tech jobs, the deflationary tendency technology has on purchasing power or most goods, lower oil prices in general, quite low inflation that would normally lead to pressure on wages and prices to rise, higher productivity with fewer hours (part-time vs full-time employment, which is more economical for a company to hire part-time if the job can be done in fewer hours).

The minimum wage is a poor measure to assess economic prosperity due to never being adjusted for inflation. But, that is an issue for a worker who is stuck in the minimum wage group. You won't be able to ever buy a house on minimum wage even if it was back in 2008 and maintain your standard of living, at least in places with notoriously high mortgage costs like California or New York.

-

apokrisis

7.8kYes, but one of the foundations upon which the USA is a vigilant and informed public. That the Republicans keep the population vigilant with invisible enemies from within and outside the borders, then that's a political issue, not an economic one. — Posty McPostface

apokrisis

7.8kYes, but one of the foundations upon which the USA is a vigilant and informed public. That the Republicans keep the population vigilant with invisible enemies from within and outside the borders, then that's a political issue, not an economic one. — Posty McPostface

The US story is about how rage at the consequences of neoliberalism - especially the way liquidity paves the way for globalisation - needs to be re-directed against other targets.

So the middleclass majority, and well-paid blue collar worker, are still befuddled as to why the economic world is running against them when clearly the US is growing ever richer.

The war on drugs, the war on weapons of mass destruction, the war on terror - these are all geopolitical moves. Excuses for the assertion of US hegemony and the side-lining of proper international political institutions like the UN. They are the public excuses for private political agendas. They are only economic moves in the sense that it feels good to the US to be in tight control of basic resources like oil.

Yes, they also serve a US desire to impose moral hegemony as well. The American Way still matters at some level of US politics. Institutions like the State Department feel missionary about these things.

But check Trump and you can see how rage is being redirected in a very anti-neoliberal theory fashion. It's plain old gut-reaction xenophobia and other-bashing.

One of the funny things about SX's PoMo Marxism is that he doesn't see how neoliberalism - as theory - advocates open borders and multiculturalism. A free market lets all ideas have a go. A pluralist competition is what is healthy.

Yet Trump harnesses the attack on this social and economic globalism. Build a wall to keep out the Mexican rapists. Every open trade deal ever done was unfair to the US. Get rid of weird folk from our military - or weird and un-american folk in general.

So we have a number of forces in play.

There is "geopolitical chessboards" - maintaining a position of US hegemony. This is about the general benefits of power, not some piffling theoretical debate about particular economic mechanisms. The politicians need to divert the populace to be free to pursue that most critical of national agendas.

Then there is neoliberalism. This is a nice theory of dissipative structure. You maximise system throughput by taking away any barriers to growth. Access to speculative capital being a key one.

In theory, for a while, broken down welfare hicks in US hicksville could be property speculators and mint a fortune. That is what equality of opportunity meant. The convenient lie told the public was that it was perfectly safe even though the US system of market oversight had been systematically deconstructed, and in the case of the credit rating agencies, plain corrupted.

Then the third sweeping force is the usual human reaction of turning inwards when feeling under attack. Rally the village, get out the pitchforks, and apply a little mob justice to anything that smacks of "other".

Here the deception of the people is simply a President agreeing it is the proper thing to do. "You want to burn the world down, sure that's a great idea. Hey maybe I'll join in and do that to North Korea."

Stale PoMo Marxism is just so inadequate as a frame of analysis. Time to speak the truth in plain language. :)

Although the US could sure do with a good dose of Scandinavian social democracy and a radical overhaul of its broken political structures. Unfortunately world governance - the UN - has been so undermined that the US can't just step away from its dreams of empire. Russia and China are just two itching to take its place.

(Well China not so much as its main existential concern is forever going to be preventing the peasants revolting against the centre. It doesn't aspire to a new colonialism, just security and stability within the traditional boundaries of its Imperial Empire.) -

Shawn

13.5k(Well China not so much as its main existential concern is forever going to be preventing the peasants revolting against the centre. It doesn't aspire to a new colonialism, just security and stability within the traditional boundaries of its Imperial Empire.) — apokrisis

Shawn

13.5k(Well China not so much as its main existential concern is forever going to be preventing the peasants revolting against the centre. It doesn't aspire to a new colonialism, just security and stability within the traditional boundaries of its Imperial Empire.) — apokrisis

And that's something I admire about China. They treat colonialism be it financial or military as a repugnant ideology. I still remember their nuclear tests being demonstrated on the backdrop of an anti-imperialist slogan on a train, which then got obliterated by the nuclear blast.

I've somewhat come to terms with the fact that the US rewards the richest above others than say valuing worker's unions and a thriving middle class. It really is a plutocracy as anyone who reads Chomsky would know. Welfare for the rich as well and thriving along with the board of the FED consisting of most major banking firms that want to keep inflation low while milking the government for more money to keep in reserves. Most people think this is a bad situation; but, where else will these people go to? China is as much as a closed-loop financial market as is the US is. So, even though their large hoards of reserves are held without entering the money stream, that money is still best secured by investment back to the FED.

I have no issues with neo-liberalism, and even have less resentment towards conservative free-market ideology even to the detriment of the population at hand if that means open markets and free trade. The invisible hand might not be infallible (climate change and tragedy of the commons) but it's the best system we've got and the Marxists are limited only to criticising the current system instead of providing a viable alternative. -

apokrisis

7.8kThe invisible hand might not be infallible (climate change and tragedy of the commons) — Posty McPostface

apokrisis

7.8kThe invisible hand might not be infallible (climate change and tragedy of the commons) — Posty McPostface

Hence the argument for a carbon tax and a national future fund.

It is just plain obvious that the active subsidising of Big Oil (which includes the massive US military spend) ought to stop. It is a market distortion proper free marketeers would abhor. Then a carbon tax is needed on top of that to pave the way to greener energy. Future generations demand it.

And why not be like Norway and actually ring-fence that income to start to pay back the damage done by galloping financial speculation?

Market principles work just fine so long as the markets are transparent enough to look sufficiently far into the future.

Another flaw in the OP is the complaint that neoliberal liquidity makes the future "a zone of indistinction".

What is actually the problem is the future is being rendered deliberately opaque by privileged interests who want to capitalise tomorrow's profits on their balance sheets today. The elite not only steal the present from the average Joe, they steal the future too.

In principle, a free market takes into account all information or self-interest. And most folk are at least modestly concerned at least a generation or two into the future.

So yes, the future has been made opaque for most people with climate denial and the lobbies against green technology or sustainable economics. But that is a product of having allowed wealth inequality develop to the point billionaires can buy administrations. It is not directly the fault of an economic theory about how best to unblock the barriers to free growth.

(Though the theory is also reckless in not clearly recognising its own downside, its need for strong regulation at government level.) -

Shawn

13.5kIn principle, a free market takes into account all information or self-interest. And most folk are at least modestly concerned at least a generation or two into the future. — apokrisis

Shawn

13.5kIn principle, a free market takes into account all information or self-interest. And most folk are at least modestly concerned at least a generation or two into the future. — apokrisis

That also depends on how informed the rational agent is. I fear, and see, that the population of the US is hopelessly misinformed about current affairs. Again, there's nothing wrong with neoliberalism as long as there aren't artificial constraints imposed on the market to balance out the workings of the economy. There's Adam Smith coming out of me. -

apokrisis

7.8kThat also depends on how informed the rational agent is. I fear, and see, that the population of the US is hopelessly misinformed about current affairs. — Posty McPostface

apokrisis

7.8kThat also depends on how informed the rational agent is. I fear, and see, that the population of the US is hopelessly misinformed about current affairs. — Posty McPostface

And not that the population is simply hopelessly irrational these days? ;)

But speaking realistically, there are always going to be artificial constraints - state intervention - in any market system. States can't in practice stand back and let themselves collapse as good market practice demands.

Sure, plenty of people would have loved Greece or Morgan Stanley to take their medicine properly. But in the end, theoretical purity is going to run into self-preservation instinct.

That is the reality the GFC should have rammed home. In the end, at some level, an economic actor becomes too big to fail.

So given that, market intervention should be something that kicks in over all scales in fair fashion. That is what bankruptcy laws were for, for example. Or monopoly laws.

If you are building a car with an accelerator, you also want to remember to build in some brakes. It's just commonsense. -

Shawn

13.5kBut speaking realistically, there are always going to be artificial constraints - state intervention - in any market system. States can't in practice stand back and let themselves collapse as good market practice demands. — apokrisis

Shawn

13.5kBut speaking realistically, there are always going to be artificial constraints - state intervention - in any market system. States can't in practice stand back and let themselves collapse as good market practice demands. — apokrisis

That's one of the dangers of the Republican laissez-faire economy. That things will take care of themselves despite leveraging the economy for persistent growth.

On a more general note, I believe in Keynesian economics; but, the efforts by the FED to increase growth by pumping money into the money stream and reaping rewards from multiplier effect will increase growth, has become largely ineffective due to keeping those funds in excess reserve funds by major institutions. What's more is that credit seems to have saturated the economy. You can get credit for anything nowadays. Sure, an individual can default due to their own mistakes; but, an entire economy of a state can't really do that. That's a real issue that's being exploited to the detriment of the entire economy from major institutions and banks. -

apokrisis

7.8kWhat's more is that credit seems to have saturated the economy. You can get credit for anything nowadays. — Posty McPostface

apokrisis

7.8kWhat's more is that credit seems to have saturated the economy. You can get credit for anything nowadays. — Posty McPostface

Yep. The economy goes sideways as it needs a good dose of inflation to wash away the debt. But it is so in debt that it can't jolt the patient to life by cutting interest rates and giving it more spending cash in its pocket. It all has to go into servicing existing debt as real production shrinks.

Next step, the deflation where the debt burden grows rather than shrinks. Whoops, apocalypse. -

Streetlight

9.1kThis is an essentially historical question, but I would like to say that a reasonable amount of the blame can be stuck on health insurance. — fdrake

Streetlight

9.1kThis is an essentially historical question, but I would like to say that a reasonable amount of the blame can be stuck on health insurance. — fdrake

Health insurance is an interesting site of analysis because while it definitely contributes to the intensification of the individual, as you put it, insurance still makes it's bed on the mattress of the calculable. That's the whole model after all: get a bunch of subscribers, calculate the risks, and charge accordingly. But the temporal shift I'm interested in consists of two things: (1) a focus on incalculable risk in the future - what might be called catastrophe risk - and (2) the correlative demand that we address such risks now precisely on account of their incalculability. Cooper quotes Stephen Haller's book on environmental catastrophe in a way that nicely captures these two dimensions:

"Some global hazards might, in their very nature, be such that they cannot be prevented unless preemptive action is taken immediately—that is, before we have evidence sufficient to convince ourselves of the reality of the threat. Unless we act now on uncertain claims, catastrophic and irreversible results might unfold beyond human control ... We must face squarely the problem of making momentous decisions under uncertainty." - but once this train of thought takes hold, action in the present becomes impossible to temporally orient. Because actions cannot be measured according to any calculable risk assessment, the borders between norm and exception break down, placing us under the 'state of exception' conditions as specified the Agamben and the like.

One consequence of this is a shift in the means of dealing with risk: no longer subject to calculability, and beset with the demand that one act now, not insurance but security becomes the focal point of action. In turn and with respect to life, the issue shifts from the insurance of life to the securitization or militerization of life in its biological register. Cooper documents a few exemplary instances of this - the treatment of the AIDS crisis in South Africa, the emergence of biosecurity discourse among the US intelligence apparatus, while Agamben has focused more on the ways in which biometric data is being increasingly employed as a vector of state security.

At the widest angle however, the biggest and most consequent danger that securitziation heralds is that of depoliticization: essentially, there is an inverse relationship between security and politics - the need to address security - now no longer reserved for exceptional situations but now immanent and incalculably of the present - displaces the space of politics. It's Agamben again who has perhaps better than most charted this shift, noting how this move to securitization is inescapably bound up with the kind of beings we are: because of the expanding sphere of biopolitics, we can be understood less and less as political actors, and more in terms of our 'bare life':

"If my identity is now determined by biological facts that in no way depend on my will and over which I have no control, then the construction of something like a political and ethical identity becomes problematic. What relationship can I establish with my fingerprints or my genetic code? The new identity is an identity without the person, as it were, in which the space of politics and ethics loses its sense and must be thought again from the ground up" And consequence of this is drawn out explicitly: "Placing itself under the sign of security, modern state has left the domain of politics." In fact it's worth reading Agamben's lecture on these themes, which ranges over this in a better way than I can given the space constraints here. -

Streetlight

9.1kYou see my problem: — apokrisis

Streetlight

9.1kYou see my problem: — apokrisis

Ahh, yes, I do now: It's that you're unfamiliar with the grade school rhetorical trope of topic sentences. Here is a guide from grammar girl that will get you up to speed:

http://www.quickanddirtytips.com/education/writing/how-to-write-a-good-topic-sentence

One step at time, we'll get you over your fear of big, scary words. And now elementary paragraph structure too. I got your back, po po. -

Streetlight

9.1kIn the end, I have to question whether a strictly economic analysis is appropriate here. I understand that this is all very political, of course, but so much of it is enabled/dictated by technological change that I don't think we can analyze it like Marxist historians looking for contradictions in the system or some such. You need to bring in a wider conceptual context to get out of your "mapping" phase, methinks. — Pneumenon

Streetlight

9.1kIn the end, I have to question whether a strictly economic analysis is appropriate here. I understand that this is all very political, of course, but so much of it is enabled/dictated by technological change that I don't think we can analyze it like Marxist historians looking for contradictions in the system or some such. You need to bring in a wider conceptual context to get out of your "mapping" phase, methinks. — Pneumenon

To be clear, if I focus on economic considerations it's because it's just so happened to be that the changes I'm trying to track (Re: risk, time, and biological life) have been largely driven by them. Had it been the case that, say, wars between nations-states had been the primary drivers of such changes, then that's where I would have focused my attention. That is to say, the focus on economics is a matter of 'following where the history takes me', rather than any essentialist conception of history that places economics at the heart of social change. It's to that extent that I find certain Marxist analyticial tools useful for this situation, specifically the thesis regarding capital's ability to liberate itself from all mediation. One can accept this without subscribing to the many other tenets which compose the Marxist edifice. -

BlueBanana

873But the temporal shift I'm interested in consists of two things: (1) a focus on incalculable risk in the future - what might be called catastrophe risk — StreetlightX

BlueBanana

873But the temporal shift I'm interested in consists of two things: (1) a focus on incalculable risk in the future - what might be called catastrophe risk — StreetlightX

Can any odds be incalculable? I think the more unexpected an event is (which is required for it to be more difficult to calculate), the smaller are its chances, and with those two factors combined, I think the combined effect of all unexpected things is a rather small one. -

Streetlight

9.1kSo, why didn't QE lead to much higher inflation rates? Or more simply, why is inflation so low in the US? — Posty McPostface

Streetlight

9.1kSo, why didn't QE lead to much higher inflation rates? Or more simply, why is inflation so low in the US? — Posty McPostface

Heh, this is the $64 million (trillion?) dollar question isn't it? As far as I know, there's no real consensus on this, but I'm very partial to the views laid out by Claudio Borio, as detailed in this FT article [possible paywall]. A snippet:

- "First, he believes that the Phillips Curve relationship has largely broken down, which implies that the decline in unemployment currently underway in many economies will not necessarily have the same effect on inflation that it has in earlier decades.

- Second, he thinks that inflation may have been permanently reduced by structural changes, including the entry of low paid workers in emerging markets into the global economy, the importance of global value chains in production, and (in future) the role of technology in increasing price transparency and reducing pricing power. He sees these factors as leading to a long lasting and benign decline in inflation, which should be broadly accepted by the central banks.

- Third, he argues that the central banks have misinterpreted some of these structural factors, and that low inflation has mistakenly led to a long standing bias towards monetary policy that is overly easy. This, in turn, leads to excess debt accumulation and destabilisation of the real economy when monetary policy is finally tightened. He thinks that the central banks should try to exit this destructive merry-go-round as soon as they can.

- Fourth, he believes that the standard approach to the definition of r*, the equilibrium real interest rate, may be wrong."

My bolding. -

Shawn

13.5k

Shawn

13.5k

One factor gets's underappreciated, IMO. Such as women entering the workforce in the US more and more. It sounds far-fetched on face value; but, should be a strong contributing factor to, again, inflation. I guess technology really has brought down prices that much.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Daniel Quinn's Ishmael: looking at the past, present, and future of humanity

- An object which is entirely forgotten, ceases to exist, both in the past, present and future.

- How can Christ be conceived as God while possesing a human body and being present for a time in Hell

- The Current Republican Party Is A Clear and Present Danger To The United States of America

- The Past, present, future, free will and determinism

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum