-

A Christian Philosophy

1.2k

A Christian Philosophy

1.2k

I agree with you; that the term 'form' is archaic. It should be seen as a temporary term early philosophers used as a place-holder until later philosophers found clearer terms to define the same things. Thus Platonic Forms (1) became 'eternal / necessary truths', Aristotle forms (2) became 'concepts' (or 'pure data' as you call it, and although I never heard that terminology before, I find it fitting too), and particular forms (3) became empirical data.

I must say I am especially disinclined to call empirical data a 'form', because it seems out of place with the other two forms (1) and (2), which have the commonality of being universals, where as form (3) does not. Furthermore, the explanation that our mind acquires empirical data directly from matter seems sufficient, without having to add another factor (form (3)) in the mix. -

Galuchat

809Thus Platonic Forms (1) became 'eternal / necessary truths', Aristotle forms (2) became 'concepts' (or 'pure data' as you call it, and although I never heard that terminology before, I find it fitting too), and particular forms (3) became empirical data. — Samuel Lacrampe

Galuchat

809Thus Platonic Forms (1) became 'eternal / necessary truths', Aristotle forms (2) became 'concepts' (or 'pure data' as you call it, and although I never heard that terminology before, I find it fitting too), and particular forms (3) became empirical data. — Samuel Lacrampe

That is essentially my current view, crystallised after reading Luciano Floridi's, Information: A Very Short Introduction (2010) and this discussion on Forms.

In addition, I equate (1) with Transcendentals, (2) with Universals, and classify both as Pure Data (Dedomena) as noted earlier.

I find MU's explanation of particular forms consistent with Aristotle's hylomorphism, and both are consistent with Floridi's definition of (empirical) data. -

Akanthinos

1k

Akanthinos

1k

Where, in that argument, do you see mention of materiality? There's none. What you have done is distinguished between two things, saying they aren't the same. They could still be made of the same stuff.

This is what I mean by saying that your argument doesn't weight in one way or another. -

Janus

17.9k↪Aaron R

Janus

17.9k↪Aaron R

But, it's real in a different sense to corporeal objects such as tables and chairs, is it not? i.e. Aquinas' ontology allows for the reality of incorporeals in a way that naturalism generally does not. — Wayfarer

↪Wayfarer

Correct. Mathematical objects are not material substances. They exist only as a nexus of relations (i.e. signs) initially abstracted from sense perception and constructively elaborated by the intellect. — Aaron R

I'm curious as to how both of you think that what Aaron says here would differ from what naturalism allows. Or to put it another why I wonder whether both of you agree that naturalism would not allow mathematical objects to exist "as a nexus of relations etc...". I would also like to hear exactly why Wayfarer thinks that, and why Aaron does, if he does. Also I would like to know whether you think this applies to all possible forms of naturalism, or only to specific forms. -

A Christian Philosophy

1.2kUnderstood. You are correct, but my previous syllogism is only step 1 of a three-step argument to prove immateriality. Step 1 proves that information is a separate thing from its container. Here is the rest.

A Christian Philosophy

1.2kUnderstood. You are correct, but my previous syllogism is only step 1 of a three-step argument to prove immateriality. Step 1 proves that information is a separate thing from its container. Here is the rest.

Step 2: Proof that info is one thing in two separate containers.

P2.1: The law of identity says that if "two" things have the exact same properties, then they are one and the same thing.

P2.2: Information A, separate from its container, is identical in container B and container C.

C2: Information A in both containers is one and the same, as opposed to being mere duplicates.

Step 3: Proof that information is non-physical.

P3.1: No one physical thing can be in two places at once.

P3.2: The same information A is obtained from containers B and C, which are in two separate places.

C3: Information is not physical. -

A Christian Philosophy

1.2k

A Christian Philosophy

1.2k

Now I still have unanswered questions. To start with, do general forms (2) exist only in our minds (excluding God's mind), or do they exist in particular things that participate in them? My answer is the latter, and here is why.

P1: It is evident that general forms (2) or concepts are the same in all minds. To assume that it could be otherwise would be absurd, because any coherent communication among individuals would be impossible: If my concept of "yes" could be your concept of "no", and so on for all concepts, then how could we hope to ever find this out, and then reach a common language on concepts? Like Meno's Paradox, we could stumble upon the same concepts by sheer luck, but then could never know for sure. Therefore, in order to avoid absurdity and despair, we must have faith that concepts are the same in all minds. This seems similar to Wittgenstein's problem that MU mentioned earlier.

P2: If the concept I perceive is the same as the one you and everyone else perceives, it is much more likely that the concept comes from outside of our minds as opposed to come from our individual minds, and coincidently is the same in all minds. To use an analogy: If I hear a piece of music, it could be either that it comes from my mind or outside; but if two persons hear the same piece of music, it is much more likely that the music comes from outside both minds.

P3: You and I likely live in different countries, and so my concept of tree-ness must have been abstracted from different particular trees than your concept of tree-ness, despite the concept tree-ness being the same.

C: General forms (2) or concepts first exist outside of our minds and inside the particular things that participate in them. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI wonder whether both of you agree that naturalism would not allow mathematical objects to exist "as a nexus of relations etc...". — Janus

Wayfarer

26.1kI wonder whether both of you agree that naturalism would not allow mathematical objects to exist "as a nexus of relations etc...". — Janus

I touched on this topic earlier in this thread, by referring to 'the indispensability argument for mathematics':

Why, you might ask, is it necessary to make such an argument at all? — Wayfarer

Because, says the IETP article on the topic:

Standard readings of mathematical claims entail the existence of mathematical objects. But, our best epistemic theories seem to debar any knowledge of mathematical objects.

This is because 'our best' epistemic theories always assume that the objects of knowledge are somehow reducible to the physical. However it then goes on to say:

Some philosophers, called 'rationalists', claim that we have a special, non-sensory capacity for understanding mathematical truths, a rational insight arising from pure thought. But, the rationalist’s claims appear incompatible with an understanding of human beings as physical creatures whose capacities for learning are exhausted by our physical bodies.

So the point of the 'indispensability argument' is

...an attempt to justify our mathematical beliefs about abstract objects, while avoiding any appeal to rational insight.

The reason that mathematical knowledge seems to conflict with 'our best epistemic theories', is because those theories are essentially physicalist in nature; they explain reason in terms of evolutionary adaption . But it's embarrassing for scientists to admit that, because they rely so heavily on mathematics. So, how to present the case for the reality of mathematical objects, 'while avoiding any appeal to rational insight'? Don't you sense the irony? Scientists are always tub-thumping about 'the importance of reason' - but their notion of 'reason' is such that it is bound by the physical sense, there can't really allow any such thing as an apodictic or self-evident rational truth. Rationalism, which used to be the jewel in the philosophical crown, is now an inconvenient truth.

In historical terms, this is because modern empiricism only recognises what the classical philosophical tradition would call 'the corporeal senses'; whereas the intuitive grasp of reason, which is such an embarrassment to empiricists, would have been similar to their 'grasp of immaterial forms' or 'the eye of reason'. But, we can't allow 'immaterial forms', so instead we have to sanitize mathematical truths to be empirically respectable.

***

do general forms exist only in our minds (excluding God's mind) — Samuel Lacrampe

I think the Augustinian answer to the above question, is to identify the divine intellect, with the 'nous' of the Platonist and neo-Platonist tradition, as the source of Forms. That is evident especially in the later Platonists, such as Proclus. -

apokrisis

7.8kMathematical objects are not material substances. They exist only as a nexus of relations (i.e. signs) initially abstracted from sense perception and constructively elaborated by the intellect. — Aaron R

apokrisis

7.8kMathematical objects are not material substances. They exist only as a nexus of relations (i.e. signs) initially abstracted from sense perception and constructively elaborated by the intellect. — Aaron R

But, it's real in a different sense to corporeal objects such as tables and chairs, is it not? i.e. Aquinas' ontology allows for the reality of incorporeals in a way that naturalism generally does not. — Wayfarer

Mathematical objects would seem to express something true about the limits of corporeality. So they speak to the reality of constraints. And they are thus real more as generals than particulars.

Consider a table or a chair. What kind of "deep maths" do they represent?

Well, as objects, they speak to symmetry-breakings and least action principles - the natural limits on concrete material actuality.

A chair or table are significant in that they break 3D space with a 2D plane. The definition of chair or table can be reduced to being "a plane" upon which we can either rest our arse or perch our elbows.

And then this is coupled to a least action principle. We want to achieve this broken spatial symmetry with the least material effort. So the plane must be supported by legs. And these would naturally be the thinnest and fewest number of supports we can manage. That is, at least three legs would be needed for a self supporting chair or table, but five or more would usually seem an extravagance.

So the maths that rules nature is about the "simplest actions" - achieving the most definite symmetry-breakings with the least amount of effort.

The debate about forms is about identifying the essence of things. As chairs and tables illustrate, the mathematical essence appears as we arrive at some universal natural principles. And the core of mathematics is about how the most difference can be produced with the least effort.

Chairs and tables are obviously objects to people. They are "chairs" and "tables" because they actually have some fit in terms of the human form, the human point of view, the way humans themselves break the symmetry of the world. So the fact that universal principles can be constraints that then harbour more particular points of view, or localised purposes, is one source of confusion in these discussions.

Then the other standard confusion is that actualised forms, or substantial forms, can freely incorporate material accidents. A chair could accidentally be brown or blue, wood or gold, etc. If the constraint is only the idea of "something suitable on which a human could balance an arse", then that definition is indifferent to many kinds of materially actual chairs.

So form is a hierarchical business - which becomes more obvious once we talk about form in terms of the causality of constraints. And form also avoids being overly-specific as, in expressing a global purpose, it doesn't need to sweat the accidental details. -

apokrisis

7.8kScientists are always tub-thumping about 'the importance of reason' - but their notion of 'reason' is such that it is bound by the physical sense, there can't really allow any such thing as an apodictic or self-evident rational truth. Rationalism, which used to be the jewel in the philosophical crown, is now an inconvenient truth. — Wayfarer

apokrisis

7.8kScientists are always tub-thumping about 'the importance of reason' - but their notion of 'reason' is such that it is bound by the physical sense, there can't really allow any such thing as an apodictic or self-evident rational truth. Rationalism, which used to be the jewel in the philosophical crown, is now an inconvenient truth. — Wayfarer

I would say rather that scientists correctly realise that the forms of nature are emergent. So everything does get tied back to the "corporeal" for a good reason. -

apokrisis

7.8kWhat? We both agree that maths talks about limiting principles, but where I stress their natural immanence, you want to claim their supernatural transcendence? Where I see limits as materially emergent regularities, you want to say they are divinely imposed accidents?

apokrisis

7.8kWhat? We both agree that maths talks about limiting principles, but where I stress their natural immanence, you want to claim their supernatural transcendence? Where I see limits as materially emergent regularities, you want to say they are divinely imposed accidents?

In your view, did God have a choice about the maths he created? Let's get at the consequences of your position and discover how rational they seem. -

Wayfarer

26.1kYou yourself talk in terms of ‘top-down causation’. What’s at ‘the top’? It’s not matter - matter is at ‘the bottom’. ‘The top’ is intentional and causative; matter has no causal efficacy of its own. That’s not even bringing ‘God’ into it; the Greek philosophical tradition didn’t see the uppermost level in terms of God, that was a consequence of its later fusion with Christian theology. But an unfortunate consequence is that if you throw out the bathwater of theism, you also discard the baby of ‘final cause’.

Wayfarer

26.1kYou yourself talk in terms of ‘top-down causation’. What’s at ‘the top’? It’s not matter - matter is at ‘the bottom’. ‘The top’ is intentional and causative; matter has no causal efficacy of its own. That’s not even bringing ‘God’ into it; the Greek philosophical tradition didn’t see the uppermost level in terms of God, that was a consequence of its later fusion with Christian theology. But an unfortunate consequence is that if you throw out the bathwater of theism, you also discard the baby of ‘final cause’. -

apokrisis

7.8kYet still, my position sees the top-down causation in terms of naturalistic emergence. It is the constraints part of the deal. And you are claiming something that is instead supernaturally existent and imposed.

apokrisis

7.8kYet still, my position sees the top-down causation in terms of naturalistic emergence. It is the constraints part of the deal. And you are claiming something that is instead supernaturally existent and imposed.

So which is it that maths describes - unavoidable regularity or some accidental divine choice?

You seem to be taking the metaphysical route which creates two further problems. It seems the maths could be different - if it is all up to some creator. And then how maths gets imposed on the world is the usual Platonic mystery.

So why isn't my self-organising metaphysics better? -

Andrew M

1.6kYou yourself talk in terms of ‘top-down causation’. What’s at ‘the top’? It’s not matter - matter is at ‘the bottom’. ‘The top’ is intentional and causative; matter has no causal efficacy of its own. — Wayfarer

Andrew M

1.6kYou yourself talk in terms of ‘top-down causation’. What’s at ‘the top’? It’s not matter - matter is at ‘the bottom’. ‘The top’ is intentional and causative; matter has no causal efficacy of its own. — Wayfarer

I think a problem is the assumption that either matter or form must be the primary constituent. On Aristotle's hylomorphism, neither is. Instead the particular is the primary constituent and matter and form are necessary aspects of the particular. So, for example, the wooden chair has four legs. It is possible to describe just the material of the chair (the wood) or just the form (it has four legs), but it is not possible to separate out either the material or the form from the chair. They are not more basic constituents. They are simply different modes of description.

It is the particular and only the particular that has causal efficacy. Why does the chair hold our weight? Because it is made of solid wood (a material cause) and has four legs (a formal cause). But matter and form are not themselves things that have causal efficacy or have an independent existence. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kHowever the passage then goes on to say that while the Forms are 'concrete', they're nevertheless not material:

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kHowever the passage then goes on to say that while the Forms are 'concrete', they're nevertheless not material:

if the intellect is an immaterial power, it receives the forms of objects in an immaterial manner. — Wayfarer

Those are the forms received within the mind that are immaterial. The form of the object itself is also immaterial, in the sense that matter and form are distinct, and one is not the property of the other. However, there must be a distinction between the form of the object itself, and the form received within the mind, or else they would be one and the same, then the material object would be in the mind. It is not though, it is what is sensed. The difference cannot simply be matter, because matter does not constitute an intelligible difference.

And if so, they can't be 'received' from anywhere, because they don't exist until the mind conceives of them. — Wayfarer

They are received by the passive intellect, from the senses and active intellect. The passive intellect receives the forms which the active intellect "creates". Remember the active intellect is similar to the good, it gives intelligible objects their essence, as "intelligible".

So if I understand you correctly, particular things must have particular forms (3) because only forms are intelligible to our minds, and matter is not. Now why is that the case? If I perceive a particular chair, why can't we not simply conclude that it is because my mind perceives the matter of the chair through direct sense data? — Samuel Lacrampe

It is simply how the terms are defined. Form refers to the actuality of what the thing is, and matter refers to the underlying potential for change. So a thing, or object must have an intelligible "what it is" (form) regardless of whether or not it has been apprehended by a mind. But Aristotle strove to make sense of change, in his physics. So he allowed that the form, what it is, changes. However, the sophists contention was that if "what the thing is", ceases to be, and a new "what the thing is" begins being, then "becoming" is not a reality. There is just a ceasing of existence of one thing, to be replaced by the existence of the next thing. In order that a thing "changes", instead of ceasing to be, and being replaced by the next thing, he posited an underlying thing, "matter", which does not change, but persists through the change. This allows us to say that a thing "changes", its form may change while it still continues to be the same thing. What we sense, and comprehend with the mind, is forms, which are capable of changing, and actually are changing. We do not sense the underlying matter which does not change. Nor do we apprehend it with the mind, it is posited as a necessary assumption to account for the temporal continuity of existence.

Sorry if I was discourteous or unkind. — Wayfarer

No apology needed here. I didn't think that at all. I just wanted to impress upon you, that I have read the material, with the serious intent to understand and nothing else, and that it is extremely difficult. Because of this difficulty there are many misinterpretations and misconceptions concerning what these authors have written, even by professors and scholars. That a group of scholars reads some passages and comes to a consensus as to what has been said, does not necessitate the conclusion that any of them actually understands the material. I don't claim to have the perfect understanding, or interpretation, Aaron corrected me already yesterday, but I do believe that I have a better than average understanding of this material.

P1: It is evident that general forms (2) or concepts are the same in all minds. — Samuel Lacrampe

Read my last paragraph directed toward Wayfarer. The fact that there are many different interpretations of the same material, misinterpretations, and misconceptions, especially with extremely difficult material like what we are dealing with here, clearly demonstrates that concepts are not the same in all minds. In the case of very simple concepts, you might argue that the concepts are "essentially" the same, in different minds. But this is to ignore the accidentals, and Aristotle's law of identity is designed such that accidentals must be accounted for, so this does not qualify as a philosophically appropriate use of "the same". -

apokrisis

7.8kInstead the particular is the primary constituent... — Andrew M

apokrisis

7.8kInstead the particular is the primary constituent... — Andrew M

Why wouldn't you say that the particular, the substantial, the entified, is the ultimate resultant?

This interpretation of Aristotle's hylomorphism makes no sense to me given the context of everything else he has to say about metaphysics.

So, for example, the wooden chair has four legs. It is possible to describe just the material of the chair (the wood) or just the form (it has four legs), but it is not possible to separate out either the material or the form from the chair. They are not more basic constituents. They are simply different modes of description. — Andrew M

Right. So in what sense is the four legged wooden chair either "primary" or a "constituent"?

It is certainly particular and constituted. It is in-formed material being. It is what it is. But it can't be a primary constituent just because it denies primary constituency to other levels or degrees of substantial being.

Clearly the four legged wooden chair just simply is a highly specified or particularised mode of description - materiality suitably constrained to the degree that it formally matters.

We could talk about its wood as a more generalised notion of materiality, its leggedness as a more generalised notion of form. The four legged wooden chair stands sharply delineated in the world due to it being so highly particular in both its material and formal qualities. And so when it comes to talk about the chair's "constitution", we can point to the general matter from which it is constructed - the wood that is its efficient/material cause. And we can point to the general forms which constrain its being - the leggedness that is its formal/final cause. The chair is some kind of high point of organised materiality in this sense.

But then we can analyse wood in the same hylomorphic fashion. And leggedness. To the degree these are emergently substantial, they can be deconstructed in both their causal directions.

So to be "constituted" is what is hylomorphic - some actualised intersection of constructing materiality and constraining formality. Hylomorphism is just another way of saying everything substantial is emergent from some particular balance of bottom-up and top-down causes.

It is the particular and only the particular that has causal efficacy. Why does the chair hold our weight? Because it is made of solid wood (a material cause) and has four legs (a formal cause). But matter and form are not themselves things that have causal efficacy or have an independent existence. — Andrew M

Again, this seems far from Aristotelean intent.

Substances of course harbour further potentials. Their enduring particularity gives character to their properties.

But the analysis of substances is in terms of the causes that produce them. It is their very being that is being explained, not their further causal efficacy.

So matter and form don't have independent existence. It is only in the unity of substance that they show their reality. Yet hylomorphism is all about how substance is emergent from the intersection of bottom-up construction and top-down constraint - the two varieties of causation in a systems view. -

Wayfarer

26.1kAnd you are claiming something that is instead supernaturally existent and imposed. — apokrisis

Wayfarer

26.1kAnd you are claiming something that is instead supernaturally existent and imposed. — apokrisis

You know that ‘supernatural’ and ‘metaphysical’ are Latin and Greek for the same word, right? Their meaning is synonymous - something like ‘above’ or ‘before’ the domain of ‘physis’. As we all know, the term ‘metaphysics’ originated with one of Aristotle’s librarians, who categorised those volumes as ‘after physics’. But it also means ‘first philosophy’ or the philosophy of first principles. And I don’t see how physics could ever be a ‘philosophy of first principles’, because the subject of physics rests on certain givens, in the sense of an existing order, namely, the domain of natural laws. Discerning those laws has enabled great scientific power, but explaining them is another matter altogether. (Peirce calls them ‘habits of nature’, although that doesn’t go that far toward explaining them.)

Historically, western culture moved from the theistic philosophy of the Christian period, towards what was hoped to be a purely naturalistic account, such that the notion of there being a sense of a divine or ordained order was no longer required. That is the overall orientation of the ‘naturalist project’. But, notice that in this outlook, the human intellect, and the human sciences, have now become the yardstick against which everything is measured. That is why naturalism looks ‘down’ as it were, to the earth on which it stands, and seeks explanations in terms of what it can materially observe and measure.

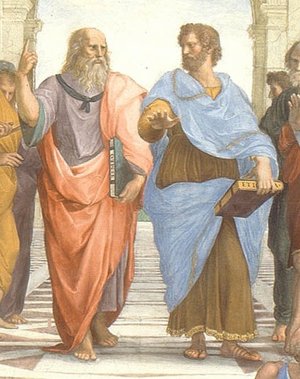

(Actually that reminds me of a comment on the famous portrait by Raphael of Plato and Aristotle in debate - the idealistic Plato on left gesturing skywards, the empirical Aristotle on the right, palm downward:

)

)

In any case, naturalism now wishes to develop what amounts to a scientific metaphysics, but I think that is a contradiction in terms, as science itself must always be, in the Aristotelian sense, a second-order enterprise; it assumes nature.

An implication of that is that any kind of understanding of metaphysics is unavoidably conjectural, as the subject of it is over our cognitive horizons, so to speak. But it is intuited in the ‘order of things’ even though it can’t directly be known. To put it a slightly different way - Perhaps you could say science is concerned with ‘what we can explain’; metaphysics with ‘what explains us’ (including the abiility we have to explain)

The only end of science, as such, is to learn the lesson that the universe has to teach it. In Induction it simply surrenders itself to the force of facts. But it finds . . . that this is not enough. It is driven in desperation to call upon its inward sympathy with nature, its instinct for aid, just as we find Galileo at the dawn of modern science making his appeal to il lume naturale. . . . The value of Facts to it, lies only in this, that they belong to Nature; and nature is something great, and beautiful, and sacred, and eternal, and real— the object of its worship and its aspiration.

The soul’s deeper parts can only be reached through its surface. In this way the eternal forms, that mathematics and philosophy and the other sciences make us acquainted with will by slow percolation gradually reach the very core of one’s being, and will come to influence our lives; and this they will do, not because they involve truths of merely vital importance, but because they [are] ideal and eternal verities. — C S Peirce

Reasoning and the Logic of Things, edited by Kenneth Lainc Ketner, (Harvard University Press, 1992), p. 11; quoted in Nagel, Thomas, Evolutionary Naturalism and the Fear of Religion, in The Last Word.

So if that’s the kind of thing you mean by ‘metaphysics’, then yes, I do have something like that in mind. -

Wayfarer

26.1kHowever, there must be a distinction between the form of the object itself, and the form received within the mind, or else they would be one and the same, then the material object would be in the mind. It is not though, it is what is sensed — Metaphysician Undercover

Wayfarer

26.1kHowever, there must be a distinction between the form of the object itself, and the form received within the mind, or else they would be one and the same, then the material object would be in the mind. It is not though, it is what is sensed — Metaphysician Undercover

D'oh! The passage in question explains that quite clearly. It says, again: 'if the proper knowledge of the senses is of accidents, through forms that are individualized, the proper knowledge of intellect is of essences, through forms that are universalized.' That is the essence of Aquinas' version of hylomorphic dualism: 'the senses' see the corporeal object, 'the intellect' grasps 'the form'. (Actually when you think about it, you can see a direct line from here to Descartes, except for Descartes' egregious error of treating res cogitans as a self-existent object.)

The passive intellect receives the forms which the active intellect "creates". — Metaphysician Undercover

One of the things I have learned in this debate, is that the active intellect creates the concept, but the form is not created by the intellect, it is received by it. -

Janus

17.9kThis is because 'our best' epistemic theories always assume that the objects of knowledge are somehow reducible to the physical. — Wayfarer

Janus

17.9kThis is because 'our best' epistemic theories always assume that the objects of knowledge are somehow reducible to the physical. — Wayfarer

OK, but in your disdain for physicalism you seem to be assuming that for the physicalist the physical is reducible to objects and/or particles rather than relations and/or processes.

Your objections would seem to evaporate if you acknowledged the processual as opposed to the substantial nature of physicality. -

Wayfarer

26.1kYour objections would seem to evaporate if you acknowledged the processual as opposed to the substantial nature of physicality. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.1kYour objections would seem to evaporate if you acknowledged the processual as opposed to the substantial nature of physicality. — Janus

Indeed, and I think the movement towards process philosophy and the ugly and incomprehensible beast called 'ontic structural realism' are a consequence of the fact that physicalism is indeed on the wane. But the notion that reason itself is the output of a purely fortuitous material process is still prevalent, so there's plenty of work to do yet. X-) -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kD'oh! The passage in question explains that quite clearly. It says, again: 'if the proper knowledge of the senses is of accidents, through forms that are individualized, the proper knowledge of intellect is of essences, through forms that are universalized.' That is the essence of Aquinas' version of hylomorphic dualism: 'the senses' see the corporeal object, 'the intellect' grasps 'the form'. (Actually when you think about it, you can see a direct line from here to Descartes, except for Descartes' egregious error of treating res cogitans as a self-existent object.) — Wayfarer

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kD'oh! The passage in question explains that quite clearly. It says, again: 'if the proper knowledge of the senses is of accidents, through forms that are individualized, the proper knowledge of intellect is of essences, through forms that are universalized.' That is the essence of Aquinas' version of hylomorphic dualism: 'the senses' see the corporeal object, 'the intellect' grasps 'the form'. (Actually when you think about it, you can see a direct line from here to Descartes, except for Descartes' egregious error of treating res cogitans as a self-existent object.) — Wayfarer

We've been through this. That's why I say there is deficiency in the human intellect. It cannot grasp the form of the individual because it only grasps universals. How is it possible for the intellect to adequately know individuals if it only grasps universal forms? And if it cannot grasp the forms of individuals, do you not agree that this is a deficiency?

One of the things I have learned in this debate, is that the active intellect creates the concept, but the form is not created by the intellect, it is received by it. — Wayfarer

Remember, it is the passive intellect which receives the form. The reason for assuming a passive intellect is to account for the receiving of the form. It receives the forms which are created by the active intellect. Aquinas asserts that the passive intellect is immaterial, but as I said to Aaron, this appears like a possible inconsistency to me. As a passive thing which "receives", the passive intellect has the nature of potential, and the real existence of potential is substantiated by Aristotle as matter. So Aquinas asserts a potential which is not of the nature of matter, and since this potential is not substantiated in the Aristotelian way, through matter, it needs to be substantiated in some other way. Otherwise it is just like an imaginary possibility. Anything which is not contradictory may be stated as a possibility, but whether or not it is a real possibility is dependent on the nature of physical reality. -

A Christian Philosophy

1.2k

A Christian Philosophy

1.2k

Got it. I figured it was likely a confusion of terms. I am personally ticked off at how freely the term 'form' is used to mean so many different things that don't seem to have any connection, but I'll deal with it.It is simply how the terms are defined. [...] — Metaphysician Undercover

I think you are using the word 'concept' ambiguously. You mean it in the sense of understanding of a sentence or text. I mean it in the sense of contingent universal forms (2). In that sense, only single words point to concepts, not whole sentences, and these are the same in all subjects that have abstracted it, as demonstrated in my previous post. Therefore, either a subject has abstracted the concept of 'redness', or he has not because he is colourblind; but there is no possibility of misunderstanding concepts.The fact that there are many different interpretations of the same material, misinterpretations, and misconceptions, especially with extremely difficult material like what we are dealing with here, clearly demonstrates that concepts are not the same in all minds. — Metaphysician Undercover

That's okay, if they are two separate things because located in different minds, it could be that my concept is an exact copy of your concept. But I don't think this is true. Since concepts are not physical, they cannot have a physical location. Instead, I think that my mind and your mind connect to the same concept. This could explain how communication is done: to communicate is to connect to the same concepts.But this is to ignore the accidentals, and Aristotle's law of identity is designed such that accidentals must be accounted for, so this does not qualify as a philosophically appropriate use of "the same". — Metaphysician Undercover -

Andrew M

1.6kWhy wouldn't you say that the particular, the substantial, the entified, is the ultimate resultant? — apokrisis

Andrew M

1.6kWhy wouldn't you say that the particular, the substantial, the entified, is the ultimate resultant? — apokrisis

That's true as well. So we would seek to explain the causes for the chair's existence in terms of other particulars. For example, the person who made it. Or the particles that it is composed of. But it is always the particular that is the locus of cause and effect whatever the mode of causal explanation.

Right. So in what sense is the four legged wooden chair either "primary" or a "constituent"? — apokrisis

In the sense that there is nothing more basic than the particular as an ontological kind. Of course the chair can be composed of further particulars (e.g., the seat and legs, or particles) - that's fine. But the chair can't be ontologically separated into matter and form. That is the false premise of dualism.

So matter and form don't have independent existence. It is only in the unity of substance that they show their reality. Yet hylomorphism is all about how substance is emergent from the intersection of bottom-up construction and top-down constraint - the two varieties of causation in a systems view. — apokrisis

So that unity of substance is ontological of which matter and form are necessary aspects. As to what constructs or constrains a substance, the answer on a hylomorphic view is: other substances. There is no formless matter or immaterial form lurking in the background. -

Wayfarer

26.1kHow is it possible for the intellect to adequately know individuals if it only grasps universal forms? — Metaphysician Undercover

Wayfarer

26.1kHow is it possible for the intellect to adequately know individuals if it only grasps universal forms? — Metaphysician Undercover

There’s your ‘unconscious modernist bias’ again. In ancient philosophy, ‘the individual’ was hardly a matter of consideration. The subject of debate was the relationship of universals and particulars. -

apokrisis

7.8kThat's true as well. So we would seek to explain the causes for the chair's existence in terms of other particulars. For example, the person who made it. Or the particles that it is composed of. But it is always the particular that is the locus of cause and effect whatever the mode of causal explanation. — Andrew M

apokrisis

7.8kThat's true as well. So we would seek to explain the causes for the chair's existence in terms of other particulars. For example, the person who made it. Or the particles that it is composed of. But it is always the particular that is the locus of cause and effect whatever the mode of causal explanation. — Andrew M

But that is just a modern atomist/reductionist notion of causality. It is far from an Aristotelean account.

So are you trying to do anything other than assimilate hylomorphism to your unquestioned atomism?

But the chair can't be ontologically separated into matter and form. That is the false premise of dualism. — Andrew M

Again, I would say the sensible understanding of hylomorphism is triadic. So it is the intersection of formal and material causes that produces the third thing of substantial being.

It is not dualism that is at the heart of things here, but the hierarchical relation of bottom-up constructive actions and top-down limiting constraints. That is how systems thinkers would read Aristotle.

As to what constructs or constrains a substance, the answer on a hylomorphic view is: other substances. There is no formless matter or immaterial form lurking in the background. — Andrew M

And yet Aristotle was concerned with the reality of prime matter and prime movers. -

Akanthinos

1kStep 2: Proof that info is one thing in two separate containers.

Akanthinos

1kStep 2: Proof that info is one thing in two separate containers.

P2.1: The law of identity says that if "two" things have the exact same properties, then they are one and the same thing.

P2.2: Information A, separate from its container, is identical in container B and container C.

C2: Information A in both containers is one and the same, as opposed to being mere duplicates. — Samuel Lacrampe

Thank you for the well thought out reply. I could go through each propositions of part 2 and 3, but honestly, I think P2.1 leaves enough of an opening for me to try and go for a quick kill.

Regarding P2.1 : Epp means each thing is identical to itself. You equivocate here if you push this to means that objects with identical properties are the same object. This is much above the level of foundational premises where Epp is located. And it happens to be false, because we happen to be in a universe filled with multiplicity. -

Andrew M

1.6kBut that is just a modern atomist/reductionist notion of causality. — apokrisis

Andrew M

1.6kBut that is just a modern atomist/reductionist notion of causality. — apokrisis

No, Democritus' atoms and the void it is not. It's instead the recognition that causality applies to hylomorphic particulars, not to mysterious immaterial forms or formless matter.

Again, I would say the sensible understanding of hylomorphism is triadic. So it is the intersection of formal and material causes that produces the third thing of substantial being.

It is not dualism that is at the heart of things here, but the hierarchical relation of bottom-up constructive actions and top-down limiting constraints. — apokrisis

What is doing the acting? Or constraining? What, on your view, would be an example of a formal cause and a material cause that does not originate in a hylomorphic substance?

And yet Aristotle was concerned with the reality of prime matter and prime movers. — apokrisis

Yes, but that is not hylomorphism, it is remnant Platonism. -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

My understanding is that experience is fundamental. All that is is relation, and substance is merely a convenient idea for understanding the dynamic-as-static. Physicality would be seen as energy, but not as 'blind' energy; so there would be no difference in ontological kind between a rational process and, for example, a chemical reaction. There would be nothing transcendent and unchanging, but all. including God, is immanent in the World. 'World' here taken to refer to the 'living world', not the the empirical world; which is merely an idea of the living world conceived as a realm of static entities. (The empirical world is of course conceived as changing but the changes are from one state to another, and the 'living' character of trans-formation itself cannot be captured). -

apokrisis

7.8kWhat is doing the acting? Or constraining? What, on your view, would be an example of a formal cause and a material cause that does not originate in a hylomorphic substance? — Andrew M

apokrisis

7.8kWhat is doing the acting? Or constraining? What, on your view, would be an example of a formal cause and a material cause that does not originate in a hylomorphic substance? — Andrew M

That's a good reply. Clearly when we are talking about actuality or being, it is always concretely substantial, always in-formed materiality. So material and formal cause can't be said to exist in some isolated, non-incarnated, way.

Yet still, the ontological question is what is the cause of being. And it is an important point that being must always be already hylomorphically developed. Two things - material and formal cause - have come together with a result, implying that those two things exist separately in their own right, and yet they can't in any proper sense exist that way.

So there is a logical bind when you get down to the root question of what causes being itself.

My triadic approach accepts that bind. That is why I say reality/being/existence is irreducibly complex. You can't dissolve what is really a process, a relation, into some simpler set of components - either a material (or idealistic) monism, or even a dualism of prime matter plus prime mover, or whatever. Bottom level is a three way hierarchical knot, a self-making process.

To make sense of that requires a further ontic dimension - the vague~crisp - which can allow existence to start off with an ultimate tentativeness yet swell and grow a definite substantiality as its own limit.

This would be the Peircean improvement on Aristotelean metaphysics. And of course it is not a well understood argument.

But you are right that the very first scrap of being would have to be already hylomorphically substantial, in some way a particular. Yet also the most general possible kind of particular. And in being the most general of all particulars, it would be the vaguest or most indeterminate state of being.

That is the logical argument. And then we can imagine this most general hylomorphic particular as "a fluctuation" - an action with a direction. So the most general notion of materiality - an action - coupled to the most general notion of a formal cause, or a constraint, which is the having of a direction.

So we can wind the clock backwards from where we stand - in a world of concrete particulars - to imagine the least concrete/most general initial conditions of hylomorphic being. A fluctuation is our best intuitive picture of this primal undeveloped state.

The very idea of an action implies a direction, and so should the very idea of a direction imply an action. We can see that each arises from the other - or at least this should be obvious since quantum mechanics showed it to be the case.

Anyway, I agree with your point - being is always already hylomorphically particular. We can't claim that material and formal cause somehow existed separately before being brought together. That's not the way it works.

But then the triadic approach says we can understand the genesis of substantial being by seeking the most generalised image of its particularity. The ontic question becomes what is the most primal incarnation of hylomorphic being? The best answer would be a fluctuation - an action~direction. That is still "a particular something" from one point of view, but it is also the most generalised, or rather the vaguest possible, particular something.

Again, if this seems a weird metaphysical claim, comfort can be found that this is just how modern physical "theories of everything" are having to imagine the creation of the Cosmos.

Loop quantum gravity approaches in particular have been finding that they all wind up back at this position of positing "bare actions" as their foundation. For mathematical reasons, attempts like causal dynamical triangulation to weave 4-dimensional models of evolving spacetimes out of "pure relations" all arrived at having to presume the notion of a bare action with a single direction. Spacetime dissolves into causal 2D shards at the primal level.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum