-

Wayfarer

26.1kTopic split from here.

Wayfarer

26.1kTopic split from here.

There's an article by Robert M. Wallace, Hegel's God, although some of it is pretty murky, in my opinion. But it is introduced with the statement that ' 'Large numbers of people both within traditional religions and outside them are looking for non-dogmatic ways of thinking about transcendent reality', of which Hegel's philosophy of religion is given as an example. — Wayfarer

Is it "murky" because it doesn't accord with the interpretation you have arrived through you own readings of Hegel's works? — Janus

No. The aspect of the argument I'm dubious about is the passage referring to the 'times when we are more fully real'. I agree with the sentiment, but I don't know if I am persuaded by the argument.

From the article you cited:

"Hegel begins with a radical critique of conventional ways of thinking about God. God is commonly described as a being who is omniscient, omnipotent, and so forth. Hegel says this is already a mistake. If God is to be truly infinite, truly unlimited, then God cannot be ‘a being’, because ‘a being’, that is, one being (however powerful) among others, is already limited by its relations to the others. It’s limited by not being X, not being Y, and so forth. But then it’s clearly not unlimited, not infinite! To think of God as ‘a being’ is to render God finite.

But if God isn’t ‘a being’, what is God? Here Hegel makes two main points. The first is that there’s a sense in which finite things like you and me fail to be as real as we could be, because what we are depends to a large extent on our relations to other finite things. If there were something that depended only on itself to make it what it is, then that something would evidently be more fully itself than we are, and more fully real, as itself. This is why it’s important for God to be infinite: because this makes God more himself (herself, itself) and more fully real, as himself (herself, itself), than anything else is."

According to this Hegel denies that God is a being and that God is "omniscient, omnipotent, and so forth". In fact logically, God cannot be anything at all if he is not a being or is not being at all. But then Wallace goes on to say that God, unlike finite things, does not depend on any relation to anything to be what He is. This is a blatant contradiction.

Process theology sees the God/ world relation as absolutely necessary; God needs the world in order to be what he is, in order to be at all, as much as the world needs God in order to be what it is, in order to be at all. The process God is a God that evolves along with the world, not a changeless transcendence. Hegel's God (as Spirit) is also like this, and I think it is likely that Hegel dissembled in relation to orthodoxy in the interests of his public image (I mean he did live in the late 18th through the early to mid 19th century after all) and quite probably also his due to a desire to support what he saw as the socially necessary institution of Christianity. — Janus

I don't read this as saying that Hegel is denying the omniscience and omnipotence of God, but of a God. As soon as you attach the indefinite article to 'God', then you have 'objectified' God - declared Him to be 'this as distinct from that'. But he says, if God is a being, then God can't be God. And that is actually quite consistent with classical philosophical theology.

This is very similar to Paul Tillich's negative theology, about which there's a brief article here. The point that Tillich frequently makes is that it is wrong to say that 'God exists', and that this is a mistake that leads towards atheism. But it's not because God doesn't exist, but is 'beyond existence and non-existence':

"Existence' - Existence refers to what is finite and fallen and cut of from its true being. Within the finite realm issues of conflict between, for example, autonomy (Greek: 'autos' - self, 'nomos' - law) and heteronomy (Greek: 'heteros' - other, 'nomos' - law) abound (there are also conflicts between the formal/emotional and static/dynamic). Resolution of these conflicts lies in the essential realm (the Ground of Meaning/the Ground of Being) which humans are cut off from yet also dependent upon ('In existence man is that finite being who is aware both of his belonging to and separation from the infinite'. Therefore existence is estrangement."

I think both Hegel's and Tillich's approaches here are 'apophatic', i.e. negative, in the sense that 'nothing can properly be said' as language itself depends on objectification and 'naming' and therefore is inadequate to deal with the scope of the matter.

Beware of the confusion that often surrounds the term 'beyond being'. What I think this term really denotes is 'beyond existence', i.e. beyond the realm of birth and death (to put it in rather Eastern terms). Which is again a reference to the transcendence or 'otherness' of deity.

As for 'God needing the world', I think any Christian would say, of course He does - why else did He wish to 'save' it? -

Cavacava

2.4kHegel's concept of alienation has to do with human powers, and needs, which form reality for a man who finds himself in a certain context or history.

Man takes needs which he can't realize, which in fact disappoint him and he posits these needs to a fictional entity which has them in abundance, and he gives that entity power over what he ought to do, thereby alienating himself from his own power. As man develops his technology and rationally, it enables him to satisfy the needs the aspects which he initally posited to god. which are overcome enabling man to now get back the powers he posited in god. God then becomes more abstract, god is love, justice and so on.

It is part of Hegel analytical method...initial meanings, a state of alienation, and then overcoming of alienation asserting new meanings. Marx adopts this schema.

His treatment of god in his aesthetic theory is different. He says (SEP):

In religion—above all in Christianity—spirit gives expression to the same understanding of reason and of itself as philosophy. In religion, however, the process whereby the Idea becomes self-conscious spirit is represented—in images and metaphors—as the process whereby “God” becomes the “Holy Spirit” dwelling in humanity. Furthermore, this process is one in which we put our faith and trust: it is the object of feeling and belief, rather than conceptual understanding. -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

If God is omniscient then he must first be, right? You can't be omniscient unless you can first be. You commit your own error of saying "he is this rather than that" by saying he is transcendent; that he is not the world or in the world. God is an infinite being; or, better, God is infinite being, but there is also a sense in which what we think of as finite beings are in-finite insofar as they are not precisely bounded or determinate. -

Wayfarer

26.1kMarx adopts this schema. — Cavacava

Wayfarer

26.1kMarx adopts this schema. — Cavacava

Only to turn it upside down.

If God is omniscient then he must first be, right? — Janus

The distinction being made here is between 'being' and 'existing'.

You might say of 'the first principle', that it IS, but not that it exists. The reason is given in that passage I quoted - 'to exist' is to be separate, to be this as distinct from that. The 'realm of existence' is the 'phenomenal realm' or, in traditional philosophical theology, 'the world' or even 'the fallen world'.

Furthermore, all finite things ('here below') are composed of parts and have a beginning and end in time - there is no particular thing to which this does not apply. So to all intents, that applies to everything that exists, every phenomenal thing ('all beings' or 'the ten thousand things' etc).

Whereas, if the first principle is not composed of parts, and doesn't begin and end in time, then how can you say of it that 'it exists'?

I think this type of understanding goes back to origins of Western metaphysics, the Parmenides: 'What is real, cannot not be, and what is not real, cannot come to be'. That began the 'dialectic of the nature of being and becoming' which was then elaborated over the subsequent centuries in theological philosophy.

there is also a sense in which what we think of as finite beings are in-finite insofar as they are not precisely bounded or determinate. — Janus

In this schema, particular beings - individuals - are created and therefore finite. In Christian doctrine, the soul might be immortal (although the details are somewhat mysterious) but the corporeal form is mortal.

This is a particular idea, with a particular history. You can find allusions to it in various philosophers and in philosophical theology. There's another OP I often link to, God Does Not Exist, by Bishop (!) Pierre Whalon. But it's hard to get the idea of apophatic theology, I do admit. -

Janus

17.9kYou might say of 'the first principle', that it IS, but not that it exists. — Wayfarer

Janus

17.9kYou might say of 'the first principle', that it IS, but not that it exists. — Wayfarer

Sure, but I didn't say God must exist, I said he must be. If God is, then God must be,which means that God is a being (albeit not a finite being). This is just a matter of the logic of the ideas; we must stick to that or we are simply talking nonsense. Of course God does cannot exist as an empirical being, that much is obvious.

But it's hard to get the idea of apophatic theology, I do admit. — Wayfarer

I am familiar enough with apophatic theology, so there's no need to be patronizing. Nothing at all can be said of God if you take the apophatic approach seriously; other than what God is not. This means we cannot say God is transcendent, immanent, omniscient, omnibenevolent, omnipotent or anything else at all. What use is such a notion of God? It constitutes a non-notion.

On the other hand its fine if you say that God cannot be known discursively, but only experientially, through affect. God then is a kind of human feeling. And Hegel does say something like this if I am not mistaken.

As for 'God needing the world', I think any Christian would say, of course He does - why else did He wish to 'save' it? — Wayfarer

I don't believe an orthodox Cristian would say that God needs the world. They might say God loves the world or cares about the world, but it is generally thought that, being omnipotent God could end the world in a heartbeat if He so willed. Of course there is an inherent contradiction involved in attributing any desire or emotion to an infinite, changeless, transcendent being. -

Noble Dust

8.1kGod then is a kind of human feeling. — Janus

Noble Dust

8.1kGod then is a kind of human feeling. — Janus

God isn't so much a human feeling in this view (the experiential view), but rather the human feeling is pointing to the reality of God. By drawing the conclusion that "God is a kind of human feeling", you're beginning with the abstract concept of God and assigning it to "human feeling" instead of actually beginning with that feeling and experientially exploring whether it leads to "God". In other words, you (I think unintentionally) are setting up a straw man in which a God only accessible via experience can't actually exist in the first place.

I don't believe an orthodox Cristian would say that God needs the world. — Janus

You're correct, they wouldn't. The theology of sin, punishment, heaven and hell all prevent this concept from being acceptable.

Actually, it's fascinating to apply the concept of "need" to God. God is said to be Love itself, for instance; perfect, unconditional love. How do Love and Need interact?

being omnipotent God could end the world in a heartbeat if He so willed. — Janus

I've never understood the point of these hypotheticals about God. What's so compelling about this idea? If he did in fact end the world in a heartbeat, we wouldn't even be around to figure out what's so compelling... :-d

I think the idea that the world is a gratuitous creation is liberating, somehow. — Wayfarer

How so? -

Wayfarer

26.1kThis might be because it is never explained to them what's the difference between "existing" and "being". — Πετροκότσυφας

Wayfarer

26.1kThis might be because it is never explained to them what's the difference between "existing" and "being". — Πετροκότσυφας

Not an easy distinction to explain, I will admit. -

Noble Dust

8.1kI guess it is supposed to explain the contingency of the world's existence by identifying God's existence with his essence, whereas our existence and essence are distinct. — Πετροκότσυφας

Noble Dust

8.1kI guess it is supposed to explain the contingency of the world's existence by identifying God's existence with his essence, whereas our existence and essence are distinct. — Πετροκότσυφας

I would re-order those terms to say that: God is essence; existence emanates from God (essence). The physical world, and we humans, are existenants; emanations.

So I wouldn't assign existence and essence as separate concepts that apply to both God and us, but in apparently different ways. Rather, essence (God) -> existence (world). -

Noble Dust

8.1k

Noble Dust

8.1k

Sure, the issue is actually that we're dealing with the most fundamental of fundamentals. But that's not begging the question; I'm not using a premise to support itself, for instance. What's actually happening is that language begins to fail here.

I'll offer a possible definition of essence: Ultimate Reality; the thing itself.

And a definition of existence: the creative emanation form essence. Our experience of existence, then, is largely an experience of the physical world, which is the creative emanation from essence.

Of course, then I would need to define "creative". -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe key is ‘the way of negation’. That is something known in both Christian and Buddhist philosophy. It sounds very complicated when you try and articulate it verbally, but that’s because it arises from non-verbal understanding, which is of course central to the contemplative practice of monks from both traditions.

Wayfarer

26.1kThe key is ‘the way of negation’. That is something known in both Christian and Buddhist philosophy. It sounds very complicated when you try and articulate it verbally, but that’s because it arises from non-verbal understanding, which is of course central to the contemplative practice of monks from both traditions.

The problem we have is that we mostly reside in the verbal/discursive layer or level of mind. That is perfectly OK as far as it goes but when it comes to dealing with ‘the fundamental principle’ it is not particularly useful. It takes meditation, but in the Eastern sense of ‘dhyana’ rather than verbally thinking something over.

Here’s an example from Buddhism. There was a series of scriptures called Prajñāpāramitā which were the initial Mahāyāna sutras. Some of them were extremely lengthy, for instance comprising 108,000 stanzas containing many abstruse philosophical distinctions. However, there is one particular form of the Prajñāpāramitā which is called ‘Prajñāpāramitā in One Letter’, that letter being the Sanskrit letter ‘A’ (अ). This is the negative particle, approximately equal to the English particle ‘un-‘ (as in unknown, unmade, etc.) That is the ‘way of negation in a single syllable’. There’s an equivalent in Zen, the Chinese character Mu, 无, which carries the same meaning.

In Western spiritual traditions, there are parallels, although of course the liturgical and dogmatic backgrounds are very different. Although, as one Zen teacher once remarked, languages are different everywhere, but hearts and lungs all work the same. ;-) -

Noble Dust

8.1kI used "begs the question", not with its logical fallacy meaning, but as an idiomatic phrase which means that a specific claim leads to a specific question. I'm not a native speaker, so if that's not really an acceptable phrase, my apologies. — Πετροκότσυφας

Noble Dust

8.1kI used "begs the question", not with its logical fallacy meaning, but as an idiomatic phrase which means that a specific claim leads to a specific question. I'm not a native speaker, so if that's not really an acceptable phrase, my apologies. — Πετροκότσυφας

No problem, I just assumed you meant the logical fallacy. But, what you're describing instead just sounds like a request for a definition of terms, which I tentatively offered.

This seems more like another name, not as a definition which explains the term by description. — Πετροκότσυφας

Ah, but now you seem to be "begging the question" by your own definition of that phrase. :) How would you go about defining "essence"? And if you have no definition, why critique mine? I ask that in good faith. In other words, you seem to either have a definition in mind yourself, or you have a reason for why you're interested in the question itself, despite not having a definition in mind. I'd like to hear either one, whichever it is. It would probably bring some clarity.

Surely, it seems like the category of existence can't apply to it, since it is prior to existence, but "prior" seems to be commonsensically understood in relation to existence. — Πετροκότσυφας

I don't use the word "prior" because it erroneously suggests that time is a component of the relationship between essence and existence. The problem here is that we have trouble imagining existence as an emanation from essence without conceptualizing "emanation" as an action; thus something that happens within time. But if we imagine that essence gives birth to the entire physical universe as we know it (3 dimensions, plus time as the so-called 4th dimension), then the problem doesn't exist; existence is, then, the given reality of the physical world.

So, it seems to me that, either this emanation you talk about is nonsensical (i.e. language fails) — Πετροκότσυφας

No; I don't equate the failure of language with "nonsense". The failure of language points to the metaphysical reality that I'm describing above.

or emanation is not temporal or causal in any way, but rather essence is a logical category immanent to the empirical world — Πετροκότσυφας

Yes, as I argued above, emanation isn't temporal or casual; however, because I don't understand your conflation of "language failing" and "nonsense", I'm not sure how "essence" as a "logical category immanent to the empirical world" follows, although it sounds interesting. -

Noble Dust

8.1k

Noble Dust

8.1k

No; the gap between philosophy and religion/mysticism needs to be bridged; tell the kids to keep off your lawn, and nothing will ever change. -

Wayfarer

26.1kWell, beg to differ. I've worked an eight-hour day all my life (although currently I'm between contracts). There are times when I don't seem connected to the teaching, but I've been practicing zazen (meditation) for most of my adult life, and it's had a big impact overall.

Wayfarer

26.1kWell, beg to differ. I've worked an eight-hour day all my life (although currently I'm between contracts). There are times when I don't seem connected to the teaching, but I've been practicing zazen (meditation) for most of my adult life, and it's had a big impact overall.

I quite admire Hegel but the German idealists, generally, were exceedingly verbose. Really after Hegel, the whole grand tradition of idealism tended to collapse under its own weight. But that article I linked to, about Hegel's philosophy of religion, resonated with me, because it is informed by a certain kind of mystical sensibility. Hence my segue into Buddhist philosophy - because that's the practice that I have found is means to realise such an understanding in day-to-day life. But also because the 'way of negation' really is a universal teaching, and I can see the connection between that, and Hegel's philosophy of religion.

And also because one of the formative books in my philosophical development was The Central Philosophy of Buddhism by T R V Murti. This was published in 1955, written by an Oxford-educated Indian scholar, who drew many parallels between Buddhism and Western idealism, particularly Hegel, Kant, and Bradley. I read it in the late 70's when I first encountered Buddhism. Indeed, his book has rather fallen out of favour as it's regarded as rather romantic and overly influenced by Kant by the current Buddhist studies academics. But I discovered Kant through it, and a connection between Kant and Madhyamika which has stayed with me ever since. -

Noble Dust

8.1kThe only definition of "essense" that I have in the back of my mind is that of the aristotelian tradition, since that's where Wayfarer takes it from. In short, it's definition usually comes in the form of: "that by which something is what it is". — Πετροκότσυφας

Noble Dust

8.1kThe only definition of "essense" that I have in the back of my mind is that of the aristotelian tradition, since that's where Wayfarer takes it from. In short, it's definition usually comes in the form of: "that by which something is what it is". — Πετροκότσυφας

Right. For my own conception, I would take it further and say that essence is Being itself. See how language becomes inadequate here? Now we're moving unto Wittgenstein's slippery ice, which is the same as the Christian Mystic's "ungrund", etc...

But what you do here is substitute "emanates from" with "gives birth to", so the problem does exist, because we conceptualise birth as action too. — Πετροκότσυφας

What? Nowhere in that quote did I substitute "emanates from" with "gives birth to".

For it to point there you have to already be aware of this metaphysical reality somehow. — Πετροκότσυφας

Right; see my comments to John about an experiential apprehension of God. I've argued nothing else. -

Noble Dust

8.1kTo be honest, I'm not sure if it's language that becomes inadequate or if it's just inadequate use of language. — Πετροκότσυφας

Noble Dust

8.1kTo be honest, I'm not sure if it's language that becomes inadequate or if it's just inadequate use of language. — Πετροκότσυφας

Can you describe why you think that?

According to you, existence emanates from being itself. Can you describe what that means? — Πετροκότσυφας

God (Being) creates (emanates) existence (the universe).

You wrote "The problem here is that we have trouble imagining existence as an emanation from essence without conceptualizing "emanation" as an action; thus something that happens within time. But if we imagine that essence gives birth to the entire physical universe as we know". — Πετροκότσυφας

Right, that wasn't consisent; "gives birth to" is a metaphor though; it can still work. What I was illustrating is that language here always presupposes a physical apparatus when trying to describe existence emanating from being. All that's needed is to acknowledge the limitation and be conscious of it; that's why "gives birth to" is a valid metaphor, but only if we're both aware that its only a metaphor. The limits of language, again.

But it doesn't seem to work. You can only find out if "it leads to "God"", if you assume the abstract concept of God in the first place. — Πετροκότσυφας

Why?

Then, there is another problem. Your last sentence, which refers to God's existence — Πετροκότσυφας

An inconsistency of terms, yes. -

Michael Ossipoff

1.7kYou people have read more theology, and authors like Hegel and Tillich, than I have, but what's been said here, in the quotes and in the discussion, makes sense to me. It seems that nothing can be said about God, other than as the possessor of the universal benevolence, good intent, that is evident behind the world.

Michael Ossipoff

1.7kYou people have read more theology, and authors like Hegel and Tillich, than I have, but what's been said here, in the quotes and in the discussion, makes sense to me. It seems that nothing can be said about God, other than as the possessor of the universal benevolence, good intent, that is evident behind the world.

Likewise the notion of God not being subject to the distinction of "existing" or "not existing".. I've been wording that by saying that God isn't an element of metaphysics.

I use the word "Reality" broadly, to include God. As for the word "is", I think it's right to say that it makes sense to distinguish it from "exists", and to only apply "exists" to elements of metaphysics.

I avoid the word "create" because it seems anthropormorphic.

Michael Ossipoff -

Janus

17.9kI wasn’t meaning to patronize, but not a lot of people get that there can be ‘non-empirical beings’. — Wayfarer

Janus

17.9kI wasn’t meaning to patronize, but not a lot of people get that there can be ‘non-empirical beings’. — Wayfarer

OK, it seemed you were implying that I was one of them, but if not then I misread you.

I think the idea that the world is a gratuitous creation is liberating, somehow. — Wayfarer

It could seem liberating in an arbitrary kind of way I suppose. That view of God holds no appeal for me. I think when we think about God, transcendence, and the like, we can only follow our imaginations and the logic of what we can, however vaguely, imagine. Or we can use poetic language to evoke the numinous. Is there another alternative? -

Janus

17.9kGod isn't so much a human feeling in this view (the experiential view), but rather the human feeling is pointing to the reality of God. By drawing the conclusion that "God is a kind of human feeling", you're beginning with the abstract concept of God and assigning it to "human feeling" instead of actually beginning with that feeling and experientially exploring whether it leads to "God". In other words, you (I think unintentionally) are setting up a straw man in which a God only accessible via experience can't actually exist in the first place. — Noble Dust

Janus

17.9kGod isn't so much a human feeling in this view (the experiential view), but rather the human feeling is pointing to the reality of God. By drawing the conclusion that "God is a kind of human feeling", you're beginning with the abstract concept of God and assigning it to "human feeling" instead of actually beginning with that feeling and experientially exploring whether it leads to "God". In other words, you (I think unintentionally) are setting up a straw man in which a God only accessible via experience can't actually exist in the first place. — Noble Dust

You have misunderstood what I said very well here!

God is known to us only as a feeling, however faint or profound. and an imagining or intuition, however vague or vivid. We develop our ideas about God from our feelings, imagination and intuitions and they can only be assessed in terms of their logical consistency. So, I think that, for example, purported logical proofs of God's existence are hopeless.

So, I am not saying that God is thought to be a "kind of human feeling", but that he is, for us, a kind of feeling. That is, if we don't feel his presence then there is no God for us. We cannot conclude anything about God's purportedly actual existence or attributes , from feeling his presence, except that he is a much greater being that we are connected with, although that doesn't prevent people from trying to.

So, you have it quite the wrong way around here, I'm not beginning from an abstract concept at all. but from the feeling of the presence of God. A God accessible only via experience may or may not "exist" or better, be, but this is not something discursively decidable in any case; rather it is something we either feel or do not, and thus have faith in or do not.

How do Love and Need interact? — Noble Dust

Somehow, it doesn't seem odd to say that God loves us, but it does to say that he needs us. I think this is a bias due to our Christian heritage. From a quite different perspective Spinoza denied that God loves the world, because his God is eternal and changeless; and it would be a mistake to impute any emotion to such a being. On the other hand, Spinoza's God in a certain sense needs us (insofar as he must have us), because the world and everything in it just as it is, is as necessary as God is. I mean in one sense of course God is a necessary being and we are merely contingent beings; but that is the purely logical sense. Ontologically speaking, because God's nature is necessary every manifestation of it is equally necessary; everything is utterly determined by that necessity, and Spinoza sees God not as possessing free will in the "absolute fiat" sense any more than he sees us as possessing free will in that sense.

I'm not arguing for Spinoza's conception of God, though; I think it is too much based on logic and not enough on affect.

I've never understood the point of these hypotheticals about God. What's so compelling about this idea? If he did in fact end the world in a heartbeat, we wouldn't even be around to figure out what's so compelling... :-d — Noble Dust

I was just pointing out that it is a common Christian conception that follows from the idea that God is omnipotent, that he doesn't need the world at all, and that the world is a gift of divine fiat and grace. I don't think God is omnipotent at all; the idea leads to too many contradictions, and also it is not something we could ever feel in any case. -

apokrisis

7.8k

apokrisis

7.8k

I was reading a nice article on Peirce/Schelling/Hegel/Emerson that you guys might appreciate. It says something deep about a "philosopher's" notion of the divine.

Returning to the Unformed: Emerson and Peirce on the “Law of Mind”, John Kaag

http://www.pucsp.br/pragmatismo/dowloads/lectures_papers/kaag-paper-04-10-12.pdf

The gist is that Hegel is like all those who make ontological arguments that presume the intelligibility of the world must reflect the already existing intelligibilty of a comprehending and reasoning mind.

But really, ontology has to start by facing the "monstrous ground" of the unformed. Pure indeterminancy or spontaneity.

Any creation story has to begin with uncomprending irrationality as its basis.

At the beginning of Peirce’s “Law of Mind,” he makes a statement that all of us know: “I have begun by showing that tychism must give birth to an evolutionary cosmology, in which all the regularities of nature and of mind are regarded as products of growth, and a Schelling-fashioned idealism which holds matter to be mere specialized and partially deadened mind." Perhaps we are less familiar with Emerson’s comment at the beginning of his “Laws of Mind” in 1870 when he states that, “I am of the oldest religion.

Leaving aside the question which was prior, egg or bird, I believe the mind is the creator of the world, and is ever creating; - that at last Matter is dead Mind.” Peirce suggests that this intellectual overlap between himself and Emerson – about matter being “deadened mind” – was a function of their shared indebtedness to German idealism, and I would argue, particularly to Schelling.

...For Schelling, they were meant to signal a break from the idealism of Hegel, which involved the working out of a well-articulated notion of reason. Schelling’s positive philosophy sought to systematically describe the relationship between the self and the objective world, like most idealist writings of his time, but it also required an account freedom that was not found in Hegel. For Schelling, as opposed to many other idealists of the time, the “alpha and the omega of philosophy was freedom.” Freedom depended on a type of existential contingency that could not be reduced to Hegelian self-mediation.

...For Schelling, as opposed to Hegel, one of these preconditions of freedom is difficult to articulate because it is the “unformed,” or what Schelling often calls the abyss or Abgrund. It is this abyss of the

unformed that serves as the curious ground, or more literally, the groundless ground, of freedom for Schelling.

...Here we begin to get a sense of what Peirce meant by “being stricken” by the “monstrous mysticism of the East.” With these eastern traditions comes a monster: the unspeakable notion that appears in Schelling’s Essay on Human Freedom, namely the idea of the Abgrund. Commentators of Peirce, such as Niemoczynski brush up against the meaning of the Abgrund (which I think he accurately identifies, following Heidgegger, as the ontological difference between nature natured and nature naturing), but he then quickly turn to the closely related concept of Firstness, which he defines as the “potentiating ground” of existence.

A surprisingly large amount is then said about Firstness – how it is possibility, potentiality, “an infinitude that sustains, enables, and empowers all else” (124) By the time we return to the topic of the Abgrund, we find, according to Niemoczynski, that “like Firstness, it remains a pre-rational ground of feeling and possibility lying incomprehensibly at the basis of all thing.”

But then he goes one step further, and perhaps one step too far: the Abgrund is the place “where the life of God swells and surges forth from within ontological difference.” I believe that this theistic reading of the Abgrund, which is certainly consonant with Boehm and Schelling, is misleading if attributed to Peirce.

Certainly, Peirce writes the “Law of Mind” on the heels of his often-cited mystical experience, at a point where he even self-identifies as a religious man, perhaps for the first time. That being said, I am uncomfortable, deeply uncomfortable, with something about this reading, namely that it invites to us rest in rather comfortable philosophical conclusion, to develop a system of religious naturalism with clean hands.

Peirce was many things, but he was not restful, and he did not have clean hands. Indeed, a quick look at his papers at Houghton Library makes one thing perfectly clear: his hands were always dirty and always moving. Approaching, experiencing, recoiling from the Abgrund, the name of the unnamable. Repeatedly. Ceaselessly. If Peirce regarded the Abgrund as the locus of God’s life, this fact did not translate into his development of a well articulated religious naturalism (like Robert Corrington’s) or a systematic philosophy (like Robert Neville’s). No, the Abgrund remained, for Peirce at least, necessarily monstrous. It repels and repels repeatedly.

This explains why Peirce and Emerson remained unwilling to systematize existence. They believed that the “unformed” of existence called for a particular kind of response. Emerson writes that “To Be is the unsolved, unsolvable wonder. To Be, in its two connections of inward and outward, the mind and nature. The wonder subsists, and age, though of eternity, could not approach a solution.” Analysis is not sufficient to approach a solution. The best that one can do is dwell in the problem.

...Figuratively speaking, a monster can be any object of dread or awe, anything with a repulsive character. The Abgrund, however, is no object. In fact, it is no-thing at all. How can no-thing at all be

monstrous?

Perhaps a word from Emerson in 1870 might help us understand: “Silent…Nature offers every morning her wealth to Man. She is immensely rich; he is welcome to her entire goods. But she speaks no word, will not as much as beckon or cough only this – she is careful to leave all her doors ajar, - towers, hall, storeroom, and cellar. If he takes her hint, and uses her goods, she speaks no word. If he blunders and starves she says nothing” (bMS Am 1280 212 (1) Harvard Lectures. Introduction “In Praise of Knowledge”).

To one that listens with all ears (to a listener like Peirce) “saying nothing” and being-silent is truly monstrous.

...For Peirce, the groundless ground, the Abgrund, serves as a warning and reminder to those that would like to tell exhaustive and determinate stories about existence, human or otherwise. It poses an unshakable question to those in search of hard and fast answers. -

Wayfarer

26.1kwhy can't we just claim that there are multiple gods or that the universe is eternal, self-caused, necessary or some such? — Πετροκότσυφας

Wayfarer

26.1kwhy can't we just claim that there are multiple gods or that the universe is eternal, self-caused, necessary or some such? — Πετροκότσυφας

Or, orbiting teapots, or the flying spaghetti monster, or....

I think when we think about God, transcendence, and the like, we can only follow our imaginations and the logic of what we can, however vaguely, imagine. Or we can use poetic language to evoke the numinous. Is there another alternative? — Janus

To discuss it under the heading 'philosophy of religion'?

Here we begin to get a sense of what Peirce meant by “being stricken” by the “monstrous mysticism of the East.” With these eastern traditions comes a monster: the unspeakable notion that appears in Schelling’s Essay on Human Freedom, namely the idea of the Abgrund.

Perhaps it's really 'the unconscious' - we become aware that we ourselves are very strange and unknown creatures. Although in Peirce's day, almost nothing was known of actual Eastern mystics -that wouldn't occur until the World Parliament of Religions, in (let's see) 1890 or so, associated with the Chicago World Fair. There, the three leading representative of the 'monstrous mysticism of the East', were Swami Vivekananda, a Vedantin, who spoke eloquently and subsequently toured the US by railroad, giving many addresses, and published a set of six books on 'the science of Yoga' which are still in circulation; Soyen Shaku Roshi, a Rinzai Zen monk who also went on to spend some time in America and arguably initiated Zen Buddhism in North America; and Dharmapala, a Sri Lankan Buddhist reformer. All unspeakable formless monsters, doubtlessly ;-)

I believe the mind is the creator of the world, and is ever creating — Emerson

In Plotinus, Nous is described as God, or more precisely an image of God, often referred to as the Demiurge. It thinks its own contents, which are thoughts, equated to the Platonic ideas or forms (eide). The thinking of this Intellect is the highest activity of life. The actualization (energeia) of this thinking is the being of the forms. This Intellect is the first principle or foundation of existence.

I'm pretty sure that is the source of the Emerson quote.

The first verse of the Dhammapada says 'what we are today comes from our thoughts of yesterday, and our present thoughts build our life of tomorrow: our life is the creation of our mind' (Mascaro translation).

There is a similarity, but also a difference. The dhammapada is not proposing an ontology - 'our life is the creation of our mind'. Whereas, in Western philosophy, to speak of 'creating the world' is about the origin of the actual cosmos.

But then, 'the world' is in some sense always 'the world as it's known by us'; we're not able to get outside of that (per Kant).

Hegel is like all those who make ontological arguments that presume the intelligibility of the world must reflect the already existing intelligibilty of a comprehending and reasoning mind. — apokrisis

But 'synthetic a priori judgements' are possible. In other words, certain predictions can be made infallibly, on the basis of premises that don't necessarily entail that conclusion by logic alone. The mind has the ability to penetrate, to some extent, the nature of things, purely on the basis of reason alone. The whole history of science is evidence of that.

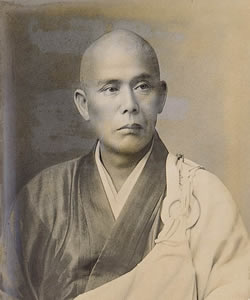

But that whole debate between Schelling and Hegel, and what Emerson and Peirce make of it, bespeaks great confusion as far as I am concerned. I think on such matters I prefer Soyen Shaku, whose book of lectures given after the World Parliament of Religions is still in print, and a model of lucid philosophical and religious reasoning.

Soyen Shaku Roshi. -

Noble Dust

8.1kBecause of the seemingly unnecessary identification of otherwise distinct concepts (essence-being), which could perform different functions in the argument. — Πετροκότσυφας

Noble Dust

8.1kBecause of the seemingly unnecessary identification of otherwise distinct concepts (essence-being), which could perform different functions in the argument. — Πετροκότσυφας

Unnecessary identification with what? I don't understand this sentence. "Essence-being" is (are?) otherwise distinct concepts, except for how I'm using them? Are you saying my usage is blurring the distinction? I honestly can't tell.

And why can't we just claim that there are multiple gods or that the universe is eternal, self-caused, necessary or some such? — Πετροκότσυφας

I don't know; why not?

What does your version of God (Being) explains that can't be explained by the other options? — Πετροκότσυφας

It's robust, as ol' VagabondSpectre would say. A single, infinite, eternal, primordial, free, un-grounded Being which is the emanator of existence. It's actually a deceptively simple idea. Our Western obsession with categorization, definition, and splintering of abstract concepts gets in the way of experiencing how "omni" the concept is.

Or maybe what we have is use of language in a context where it's not meant to be used. — Πετροκότσυφας

Right...the limits of language...

But even if we accept that it's a metaphor, what is it a metaphor for? — Πετροκότσυφας

For how the known universe came into existence. Clearly...

If the metaphor is all we have, we don't seem to have much. — Πετροκότσυφας

No; metaphor is the basis and structure of language itself. That means it's the structure of how we perceive the world through experience. -

Wayfarer

26.1kwhich is the emanation of existence — Noble Dust

Wayfarer

26.1kwhich is the emanation of existence — Noble Dust

emanator, I would have thought, i.e. 'existence' emanates from this, not vice versa. -

Noble Dust

8.1kGod is known to us only as a feeling, however faint or profound. — Janus

Noble Dust

8.1kGod is known to us only as a feeling, however faint or profound. — Janus

Ok, I hate to play this card, but, in good faith, can you define "feeling" here? It would be helpful.

We develop our ideas about God from our feelings, imagination and intuitions and they can only be assessed in terms of their logical consistency. So, I think that, for example, purported logical proofs of God's existence are hopeless. — Janus

First, I don't quite agree, because I don't rule out the possibility of actual, real, connection with and/or direct experience of God. I'm reading Evelyn Underhill's "Mysticism" currently (thanks to 's rec), and am feeling quite at home. But of course, it's hard to make a philosophical argument for the reality of direct experience of God...

But, that's exactly the reason why I agree with your second statement; logical proofs don't do much for me either, but for the reasons stated above.

So, I am not saying that God is thought to be a "kind of human feeling", but that he is, for us, a kind of feeling. — Janus

That's the same thing still. Look at those two phrases: "a kind of human feeling" and "he is, for us, a kind of feeling".

So, you have it quite the wrong way around here, I'm not beginning from an abstract concept at all. — Janus

Ok, I see that now, yes.

A God accessible only via experience may or may not "exist" or better, be, but this is not something discursively decidable in any case; rather it is something we either feel or do not, and thus have faith in or do not. — Janus

I agree, except that I always place priority on experience. Because, as I've attempted to argue many times, experience is reality. Nothing escapes the realm of experience, not even logical proofs for or against God's existence; not even discursive reasoning to bolster an argument for or against. The strongest logical proofs from the most brilliant minds are still mere moments in the constant stream of experience.

Somehow, it doesn't seem odd to say that God loves us, but it does to say that he needs us. I think this is a bias due to our Christian heritage. — Janus

It is. It took me quite awhile to accept my nagging intuition that God has need for man.

I'm not arguing for Spinoza's conception of God, though; I think it is too much based on logic and not enough on affect. — Janus

I agree. It's murky territory, though. Viewing God as Being which emanates existence (of which we are a part), it's easier to imagine not that God needs us and us him/her (logically), but rather that we are literally a generative aspect of the divine, thus inseparable. So the concept of "need" sort of falls flat, and it's rather an inexorable teleological movement towards irresistible future Union. Love isn't so much the mechanism of that movement, then, but rather a description of that irresistible movement. -

Janus

17.9kI think when we think about God, transcendence, and the like, we can only follow our imaginations and the logic of what we can, however vaguely, imagine. Or we can use poetic language to evoke the numinous. Is there another alternative? — Janus

Janus

17.9kI think when we think about God, transcendence, and the like, we can only follow our imaginations and the logic of what we can, however vaguely, imagine. Or we can use poetic language to evoke the numinous. Is there another alternative? — Janus

To discuss it under the heading 'philosophy of religion'? — Wayfarer

It seems to be irrelevant what heading we discuss it under. How would we discuss it "under the heading of philosophy of religion" other than by thinking "about God, transcendence and the like" by following "our imaginations and the logic of whatever we can, however vaguely, imagine."? Is there another methodology separate from imagination and logic when it comes to metaphysics or philosophy of religion or whatever you want to call it, and if so what do you think it is? -

Noble Dust

8.1kYou wrote "God is essence". Then you gave it other names too, Being, Being Itself, Thing In itself, Ultimate reality etc. So, I took it that you identified them. For example, a thomist would not do that, he would identify essence as that by which something is what it is, so that he could argue, among lots of other things, that the world's essence is distinct from its existence, that is to say its existence is contingent, while God's essence is identical with Its existence, that is to say, God is His act of existence, Being itself, ipsum esse subsistens. To do that, he needed not just the concept of existence but that of essence as well. An option which is not open to you if you're going to use "essence" as just another name for Being. — Πετροκότσυφας

Noble Dust

8.1kYou wrote "God is essence". Then you gave it other names too, Being, Being Itself, Thing In itself, Ultimate reality etc. So, I took it that you identified them. For example, a thomist would not do that, he would identify essence as that by which something is what it is, so that he could argue, among lots of other things, that the world's essence is distinct from its existence, that is to say its existence is contingent, while God's essence is identical with Its existence, that is to say, God is His act of existence, Being itself, ipsum esse subsistens. To do that, he needed not just the concept of existence but that of essence as well. An option which is not open to you if you're going to use "essence" as just another name for Being. — Πετροκότσυφας

I'm not a Thomist, so...I don't know. My concept still stands against what you're saying here, as far as I can see.

Why not what? — Πετροκότσυφας

You asked "why not" originally here, so you tell me.

but the difficult thing to do is to explain in understandable language (since you express these properties in language as well) what they mean and show why they apply to A and not to B. — Πετροκότσυφας

Right, it's difficult because it's impossible, because logic isn't the correct tool to use to apprehend the concept.

Or its bad usage. — Πετροκότσυφας

No, don't misquote. You said:

Or maybe what we have is use of language in a context where it's not meant to be used. — Πετροκότσυφας

To which I said:

Right...the limits of language... — Noble Dust

Clearly that is a generality and as such is not informative in the least. A doctor can tell you the exact process of human birth. That is to say, when he uses the name "birth" there's something specific this name refers to. So, if he uses a metaphor for "birth", I know where this metaphor ultimately refers to because I know where "birth" refers to. It's not referring just to another name (i.e how babies exit the womb), it refers to a specific process. — Πετροκότσυφας

What??? A metaphor describes a concept in non-literal terms, via equating two otherwise disparate concepts or objects. You're literally describing to me right now how a doctor can literally describe birth as a literal process. That has nothing to do with metaphor.

No, it's not. Unless you were using "metaphor" metaphorically. — Πετροκότσυφας

Existence, being, and metaphor all disagree with you, and that just based on a shallow Google search. -

Janus

17.9kOk, I hate to play this card, but, in good faith, can you define "feeling" here? It would be helpful. — Noble Dust

Janus

17.9kOk, I hate to play this card, but, in good faith, can you define "feeling" here? It would be helpful. — Noble Dust

Don't we all know what feeling is? An emotion that moves us? For example do you know love if you have not felt it? Why should it be different with God?

First, I don't quite agree, because I don't rule out the possibility of actual, real, connection with and/or direct experience of God. — Noble Dust

How do you think we would experience that other than as a feeling? It cannot be merely an idea, no?

But of course, it's hard to make a philosophical argument for the reality of direct experience of God... — Noble Dust

The reality of the experience is in the reality of the feeling, isn't it? Where else? Of course you can have faith that the reality of the feeling shows you that God is a reality, but we don't even know what God's independent reality could mean, any more than we know what the independent reality of anything we experience could mean.

That's the same thing still. Look at those two phrases: "a kind of human feeling" and "he is, for us, a kind of feeling". — Noble Dust

There is a logical distinction between how we experience God (as a feeling) and how we think of God (as something beyond, and yet co-originary of, our feeling, for one possible example)

I agree, except that I always place priority on experience. Because, as I've attempted to argue many times, experience is reality. Nothing escapes the realm of experience, not even logical proofs for or against God's existence; not even discursive reasoning to bolster an argument for or against. The strongest logical proofs from the most brilliant minds are still mere moments in the constant stream of experience. — Noble Dust

So, for you God cannot be both in and beyond our experience? If God cannot "escape the realm of experience" then he cannot be an independent entity at all, but would remain confined to the human feeling of his presence.

it's easier to imagine not that God needs us and us him/her (logically), but rather that we are literally a generative aspect of the divine, thus inseparable. — Noble Dust

If we think of God as the origin of our experience, of our very selves, then logically in that sense we need him more than he needs us. He is a necessary being whose essence it is to exist, and we are contingent beings, whose essence does not entail existence, as per Spinoza.

.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum