-

BC

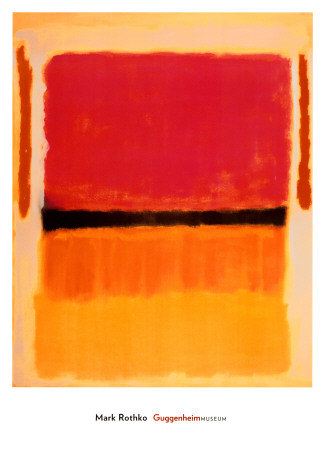

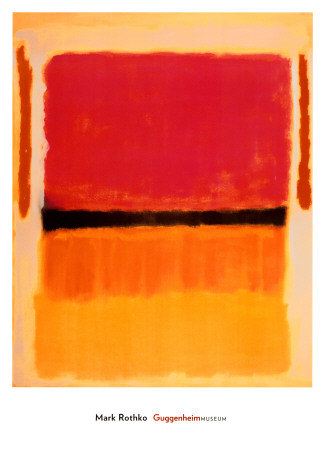

14.2kFrom one angle I find works by Rothko and Pollock visually pleasing, but from other angles they can seem empty and dull. They attract considerable loathing.

BC

14.2kFrom one angle I find works by Rothko and Pollock visually pleasing, but from other angles they can seem empty and dull. They attract considerable loathing.

Abstract expressionism (A.E.) has a history, of course, just like impressionism or any other movement in art has. A.E. loathers think it is all shit, but it seems to me that there is a real difference between "the established artists" whose works sell for $$$$ (like Pollock) and slap-dash stuff that would-be A.E. artists and opportunists put up on sites like Tumblr or local art fairs.

What makes your paint dribbling experiments better than mine, or either less than Pollock's? If we paint 3 colored squares, why isn't that as good as Rothko?

One reason why my A.E. messes are nothing more than decoration is that "the moment" of abstract expressionism has passed. Dribbling paint can't be a statement in 2015, it can only be a shallow, derivative 'trick'.

What is the movement of the moment?

-

Moliere

6.5kIt's actually extremely difficult to replicate A.E. works of art. Just imagine trying to get even that Rothko painting exactly correct.

Moliere

6.5kIt's actually extremely difficult to replicate A.E. works of art. Just imagine trying to get even that Rothko painting exactly correct.

And then, there's something to be said about having an artist create A. E. and having your Uncle say that he can do that too. One, I bet the Uncle didn't do that. They just feel like they could. I'd encourage them to try. Two, the artists we are familiar with tend to create better A.E. pieces than someone who is just trying it out. They are more visually pleasing, on the whole -- because the artist is trained in the principles of art, and practiced too.

In addition there's the originality of the works, as you note. But I see no reason why a modern A.E. couldn't do well, insofar that they just did something different with it. I rather like the paintings, personally. I spent a whole day in MOMA once, just looking. I was drawn into the abstract works more than the "explicit" works. -

Mayor of Simpleton

661I can't explain it.

Mayor of Simpleton

661I can't explain it.

I could just as well say that I can actually visually 'feel the texture and temperature', 'taste the flavor of colors', 'hear the movement just hanging there' and 'smell the depth and perspective' of the painting of Jasper Johns or Pollock or Rauschenberg. :B

My main criteria of art is 'does it appeal to me'. How it appeals depends upon when and where you ask me. It just works.

I have an apartment full of various works of art. Some of the artists are known and others not. I just simply collected what appealed to my senses. (My wife recently talked me out of buying a Rauschenberg when In Nizza... gee whiz! It was rather inexpensive... oh well.)

As for why your drippings and droppings are not as valued by me...

... I've never seen them, so I can't say for sure.

Meow!

GREG -

BC

14.2kTo draw a comparison in music: I listen to a lot of baroque music. the Bachs, Buxtehudes, et al. Sometimes at concerts I will doze off, waking up for the applause.

BC

14.2kTo draw a comparison in music: I listen to a lot of baroque music. the Bachs, Buxtehudes, et al. Sometimes at concerts I will doze off, waking up for the applause.

I don't care for a lot of contemporary orchestra or voice music (though I love some of it). But I rarely doze off during contemporary music. This stuff often requires considerable intellectual engagement. One may get up and walk out, or listen raptly, but one won't fall asleep. -

Mongrel

3kWhat is the movement of the moment? — Bitter Crank

Mongrel

3kWhat is the movement of the moment? — Bitter Crank

There's a PBS show called Art21 which presents various contemporary artists and their work. A lot of it is about artists creating environments.. like sculptures the public walks through... lots of videos.. one lady sits members of the public down and just stares into their eyes. Weird, but fun. -

Sentient

49I always saw A.E as a counter-reaction to the Impressionists. The ultimate rebellion, if you will and I've never cared for either movement. If you accept that Art moves in cycles (or used to before smart phones) then it's the minimalistic version of Daidism, they in turn are attempting a crude form of Surrealism, in my opinion.

Sentient

49I always saw A.E as a counter-reaction to the Impressionists. The ultimate rebellion, if you will and I've never cared for either movement. If you accept that Art moves in cycles (or used to before smart phones) then it's the minimalistic version of Daidism, they in turn are attempting a crude form of Surrealism, in my opinion. -

BC

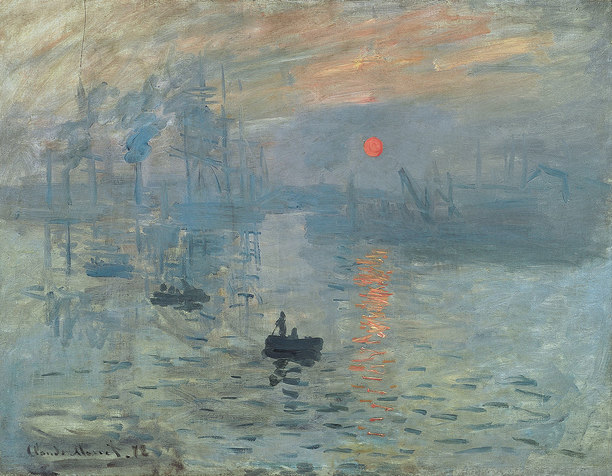

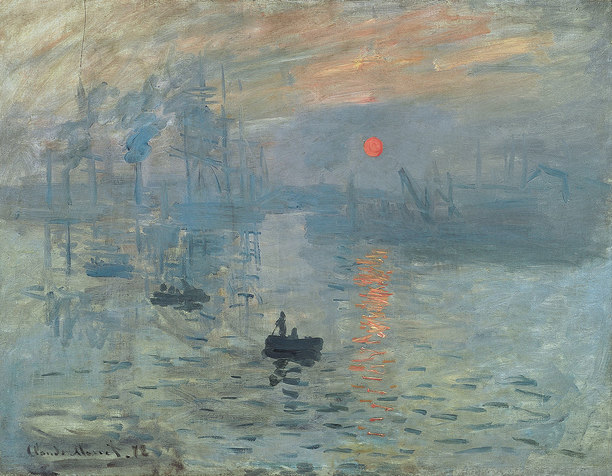

14.2kClaude Monet, Impression, soleil levant

BC

14.2kClaude Monet, Impression, soleil levant

The term, "impressionism" was initially used satirically in a review of Soleil Levant (Sunrise).

-

Dada was an informal international movement, with participants in Europe and North America. The beginnings of Dada correspond to the outbreak of World War I. For many participants, the movement was a protest against the bourgeois nationalist and colonialist interests, which many Dadaists believed were the root cause of the war, and against the cultural and intellectual conformity—in art and more broadly in society—that corresponded to the war.[7]

Many Dadaists believed that the 'reason' and 'logic' of bourgeoisie capitalist society had led people into war. They expressed their rejection of that ideology in artistic expression that appeared to reject logic and embrace chaos and irrationality. For example, George Grosz later recalled that his Dadaist art was intended as a protest "against this world of mutual destruction."[8]

According to Hans Richter Dada was not art: it was "anti-art."[7] Dada represented the opposite of everything which art stood for. Where art was concerned with traditional aesthetics, Dada ignored aesthetics. If art was to appeal to sensibilities, Dada was intended to offend.

As Hugo Ball expressed it, "For us, art is not an end in itself ... but it is an opportunity for the true perception and criticism of the times we live in."[9]

A reviewer from the American Art News stated at the time that "Dada philosophy is the sickest, most paralyzing and most destructive thing that has ever originated from the brain of man." Art historians have described Dada as being, in large part, a "reaction to what many of these artists saw as nothing more than an insane spectacle of collective homicide."[10]

Years later, Dada artists described the movement as "a phenomenon bursting forth in the midst of the postwar economic and moral crisis, a savior, a monster, which would lay waste to everything in its path... [It was] a systematic work of destruction and demoralization... In the end it became nothing but an act of sacrilege."[10]

To quote Dona Budd's The Language of Art Knowledge,

Dada was born out of negative reaction to the horrors of the First World War. This international movement was begun by a group of artists and poets associated with the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. Dada rejected reason and logic, prizing nonsense, irrationality and intuition. The origin of the name Dada is unclear; some believe that it is a nonsensical word. Others maintain that it originates from the Romanian artists Tristan Tzara's and Marcel Janco's frequent use of the words "da, da," meaning "yes, yes" in the Romanian language. Another theory says that the name "Dada" came during a meeting of the group when a paper knife stuck into a French-German dictionary happened to point to 'dada', a French word for 'hobbyhorse'. (Wikipedia) -

BC

14.2kSometimes one can see a nice historical progression in art, sometimes not. I used to think "Modern Art" was stuff that had been painted since WWII. I was shocked (shocked!) to discover it had begun roughly 60 years earlier when precise figure, or representational art, was pretty much abandoned by "serious artists".

BC

14.2kSometimes one can see a nice historical progression in art, sometimes not. I used to think "Modern Art" was stuff that had been painted since WWII. I was shocked (shocked!) to discover it had begun roughly 60 years earlier when precise figure, or representational art, was pretty much abandoned by "serious artists".

Wassily Kandinsky started out as an approximately figurative artist (1908), but over the course of a decade or so developed a style (1923) that predates abstract expression by a world wide depression and another world war IWWII). Dada too seems to prefigure abstract expressionism too. (I'm not suggesting Kandinsky was a Dadaist.)

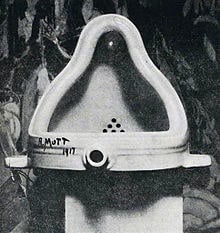

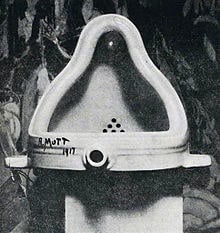

Duchamp's Urinal is as good an example of Dada as any. I don't take it as ridiculous or stupid, but context is very important, in any art evaluation.

"Everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics" applies to art and philosophy. The alleged nihilism of the current young generation didn't just happen. It's a political/philosophical/artistic/social phenomenon.

-

Thorongil

3.2kI think in some ways the question is inapplicable to these creations. I tend to think the point, perhaps, is that there isn't anything to necessarily think about.

Thorongil

3.2kI think in some ways the question is inapplicable to these creations. I tend to think the point, perhaps, is that there isn't anything to necessarily think about.

A painting of, say, the crucifixion from some Renaissance master is pretty straight forward in terms of what it's conveying and what we are to think and feel about it. But a lot of modern art is deliberately un-straight forward in terms of what it's trying to convey and how we are to react to it. Take Duchamp's Fountain, as you show us above. What the hell am I supposed to think when seeing some New York urinal? Who knows. Maybe even Duchamp doesn't know.

This is actually the reason why I don't like this kind of "art." It strikes me as a pointless waste of time, since art for me is transportative - it takes me out of myself for a short while - whereas staring at a urinal or some paint splotches on a canvas do not have such an effect. They mostly make me irritated. There are exceptions, of course, but modern art has always rubbed me the wrong way. -

Sentient

49Interesting points about pessimism and art, Bitter Crank. What does this mean in a world where art is all but a goner? Unless you want to count deviantart and instagram as 'art'.

Sentient

49Interesting points about pessimism and art, Bitter Crank. What does this mean in a world where art is all but a goner? Unless you want to count deviantart and instagram as 'art'.

Thorongil, I sympathize with your stance on modern art although I always promised myself not to judge others' taste in art. -

Sentient

49@Thorongil Ha! It's easy to embrace one's cynicism and that much harder to embrace one's joy, I've found. An interesting dichotomy when considering you're in agreement with Plato that 'the good attracts the good'. This I'd question after having read little red riding hood a few times. ;)

Sentient

49@Thorongil Ha! It's easy to embrace one's cynicism and that much harder to embrace one's joy, I've found. An interesting dichotomy when considering you're in agreement with Plato that 'the good attracts the good'. This I'd question after having read little red riding hood a few times. ;) -

Moliere

6.5kKant's aesthetics -- formally speaking -- are actually really excellent for judging abstract works of art.

Moliere

6.5kKant's aesthetics -- formally speaking -- are actually really excellent for judging abstract works of art.

That is, it is you who should appreciate them on purely normative grounds, whatever your particular enjoyments might be. ;) -

Sentient

49@Thorongil, I have never been too sure of this because it wouldn't explain the interplay of magnetism and poles or most (though not all) mathematical models.

Sentient

49@Thorongil, I have never been too sure of this because it wouldn't explain the interplay of magnetism and poles or most (though not all) mathematical models.

It has always seemed an unsolvable dichotomy from where I stand. -

Jamal

11.6kI think in some ways the question is inapplicable to these creations. I tend to think the point, perhaps, is that there isn't anything to necessarily think about.

Jamal

11.6kI think in some ways the question is inapplicable to these creations. I tend to think the point, perhaps, is that there isn't anything to necessarily think about.

A painting of, say, the crucifixion from some Renaissance master is pretty straight forward in terms of what it's conveying and what we are to think and feel about it. But a lot of modern art is deliberately un-straight forward in terms of what it's trying to convey and how we are to react to it. Take Duchamp's Fountain, as you show us above. What the hell am I supposed to think when seeing some New York urinal? Who knows. Maybe even Duchamp doesn't know.

This is actually the reason why I don't like this kind of "art." It strikes me as a pointless waste of time, since art for me is transportative - it takes me out of myself for a short while - whereas staring at a urinal or some paint splotches on a canvas do not have such an effect. They mostly make me irritated. There are exceptions, of course, but modern art has always rubbed me the wrong way. — Thorongil

You seem to be lumping together abstract paintings with Duchamp's urinal, all under the category of "modern art". In doing so, there's a lot you will miss. Duchamp's urinal is one of the first examples of what we now call conceptual art. This is art that mocks artistry, skill, training and mastery, and renounces what was always fundamental in art: the artist as maker, applying his or her hand to a material. Many conceptual works, like those of Damien Hirst, are not actually made by the artist; they are assembled by assistants or gallery staff according to the artist's instructions. When challenged on this practice Hirst speaks with contempt about those who apply their own artistry: "A man who is great with his hands might as well make macramé." Apparently it is the job of artists to create concepts. The true artist then, for Hirst, is now a kind of stunt philosopher.

When you complain about "modern art" what you don't see is that this conceptual stuff is a world away from what painters such as Rothko, Pollock, Kandinsky, and Picasso were doing. These were brilliant, immensely skilled people who were driven to stand in front of a canvas and make things (Picasso for instance is widely considered to be one of the most technically accomplished painters of the twentieth century). I would say, that is, that they were true artists.

I am not seeking to change your taste—there is no special reason why you should be interested in looking at colours and shapes and textures arranged in certain ways—but I would like you to consider a different way of looking at abstract paintings, and at least recognize that, unlike charlatans such as Damien Hirst, these painters were doing something eminently, even traditionally artistic. They were making objects for people to look at, with their own hands, struggling to capture or explore aspects of nature and perceptual experience. These objects didn't usually have a message. They didn't usually try to tell stories. Rather, they invited people just to use their eyes, for the hell of it. What can be more straightforward than that?

Skilled, trained, and dedicated painters, who wanted to make a mark on the world, and who a hundred years before would have painted figuratively, wanted to try different ways of representing reality, or they wanted to explore, among many other things, the beauty, balance, and sense of energy, space, or movement that is achievable by the manipulation of basic forms and colours and textures. These paintings don't have to mean anything. Even so, I would class these artists as maintaining a millennia-long tradition, one of personal mastery and creativity.

It's easy to dismiss Pollock, but he didn't apply the paint randomly. His paintings were made with utmost care, and the result is expanses of paint with a buzzing sense of both harmony and chaos, fascinating to look at. And the Rothko, just look at it! Imagine the sheer optical pleasure of standing in front of that towering glowing canvas, and the intellectual satisfaction inherent in the experience of being confronted with one's own perception. People want to make such things because they see how deeply beauty runs through the world, right down to its basic constituents, and they have an urge to make things nobody has seen before, to extend the field of what can be made.

Even if you think abstraction is a blind alley, that a painting cannot be transportative without being figurative, it is really quite unfair on these painters to associate them with conceptual art.

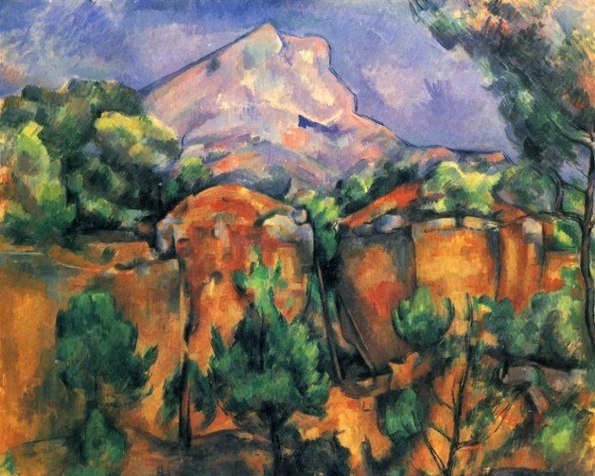

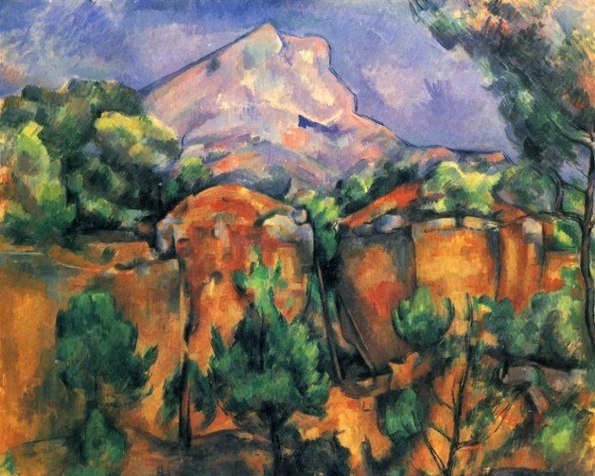

And just where do you draw the line between the figurative and the abstract? What do you think of these landscapes by Turner, Cézanne, and Strindberg?

Maybe I can disarm you with an appeal to Schopenhauer. As you know, for him music was the highest art, and within the realm of music he placed absolute music, which is not about anything in particular, above program music, which is tied to a non-musical narrative (a love affair, the seasons of the year, and so on). Music, when done right...

...does not express this or that individual or particular joy, this or that sorrow or pain or horror or exaltation or cheerfulness or peace of mind, but rather joy, sorrow, pain, horror, exaltation, cheerfulness and peace of mind as such in themselves, abstractly… — Schopenhauer, WWR 289

If abstraction is so good in music, then why not in visual art? I'm not saying that it is equal to music in its range and depth, and it is true that abstract art cannot evoke the emotions as music can, but there is much it can do without the burden of narrative and representation. If Schopenhauer had lived later and been less temperamentally conservative I think he might have approved of abstract painting.

And perhaps, @Bitter Crank, some of the above goes a way towards responding to your questions in the OP. I think I know what you mean when you say these works can seem, under a certain aspect, "empty and dull", though I don't think I agree.

There's something wonderful that John Cage once said:

When I hear what we call “music”, it seems to me like someone is talking; and talking about his feelings or about his ideas or relationships. But when I hear traffic, the sound of traffic, here on Sixth Avenue for instance, I don’t have the feeling that anyone is talking. I have the feeling that sound is acting. And I love the activity of sound. I don't need sound to talk to me, I'm completely satisfied with it by itself.

If I say that abstract art is somewhat akin to this attitude—for example I might say that painters no longer wanted their paintings to chatter at the spectator but instead allow space and colour to act—then it might be asked, "so what?" Isn't this a bit vacuous, a bit non-committal? A bit empty and dull? My answer, other than "not really", will have to wait. -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

From: http://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-arts-and-culture/books/101723/a-philosopher-of-small-thingsThe best example of anti-art, Groys writes, is Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 “Readymade Fountain.” Duchamp signed (under the name R. Mutt) and dated a store-bought, mass-made, porcelain urinal and then exhibited it. Is the urinal art? Does it do what art is supposed to do? Once it’s been moved into a gallery space, Duchamp suggests, the answer is decisively yes. And what is art supposed to do, anyway? If a viewer gives the urinal—or fountain, rather—the same kind of concentrated attention one gives a work by Monet, is it any less of an aesthetic experience? Duchamp seems to be saying that the creativity and craftsmanship one sees in excellent works of fine art can be found lining the walls of public restrooms, if only one is able to look at those urinals in a certain way. Beauty is not just in the eye of the beholder, anti-art points out, but is invented in the eye of the beholder.

Anti-art’s aim is not to rob art of its purpose but to democratize it, to make it clear that the bathroom has as much aesthetic interest as the gallery if only one is able to change one’s mindset.

That's just some interesting stuff I came upon these last few days that I just got reminded of when I saw the picture of the "Readymade Fountain" here. Not that I agree with it; personally I don't like the urinal, and I do agree with Thorongil that it does not give me an aesthetic experience which makes my mind come to a halt and become fully present, with no will, passions, or desires left. -

Thorongil

3.2kYou seem to be lumping together abstract paintings with Duchamp's urinal, all under the category of "modern art". — jamalrob

Thorongil

3.2kYou seem to be lumping together abstract paintings with Duchamp's urinal, all under the category of "modern art". — jamalrob

I probably am. I like Western art up until about the year 1920 or so. Most of the art created after this date irritates me. So I freely admit my knowledge of art history is largely determined by the art I like.

Duchamp's urinal is one of the first examples of what we now call conceptual art. This is art that mocks artistry, skill, training and mastery, and renounces what was always fundamental in art: the artist as maker, applying his or her hand to a material. Many conceptual works, like those of Damien Hirst, are not actually made by the artist; they are assembled by assistants or gallery staff according to the artist's instructions. When challenged on this practice Hirst speaks with contempt about those who apply their own artistry: "A man who is great with his hands might as well make macramé." Apparently it is the job of artists to create concepts. The true artist then, for Hirst, is now a kind of stunt philosopher. — jamalrob

They ought to have written books, then. What they're doing is not art. But if they freely admit to being unskilled smartasses, then nothing more needs to be said.

They were making objects for people to look at, with their own hands, struggling to capture or explore aspects of nature and perceptual experience. These objects didn't usually have a message. They didn't usually try to tell stories. Rather, they invited people just to use their eyes, for the hell of it. What can be more straightforward than that? — jamalrob

Yeah, I don't have a problem with this at all.

What do you think of these landscapes by Turner, Cézanne, and Strindberg? — jamalrob

I don't mind them. I especially like the third painting, actually, despite my comment earlier about paint splotches. By contrast, though, the two paintings BC linked in the OP I think are horrid, along with Duchamp's Fountain. But notice how all three artists (Rothko, Pollock, and Duchamp) were primarily active well after my 1920 cut off date. If "modern art" includes the paintings you linked, the impressionists, and the symbolists, then I can say I do like modern art. Whatever one uses to call the predominant forms of "art" after about 1920 is what I am almost universally repelled by. Is there a term for that or is it just "conceptual art" as you mentioned above? -

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1kIf "modern art" includes the paintings you linked, the impressionists, and the symbolists, then I can say I do like modern art. Whatever one uses to call the predominant forms of "art" after about 1920 is what I am almost universally repelled by. Is there a term for that or is it just "conceptual art" as you mentioned above? — Thorongil

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1kIf "modern art" includes the paintings you linked, the impressionists, and the symbolists, then I can say I do like modern art. Whatever one uses to call the predominant forms of "art" after about 1920 is what I am almost universally repelled by. Is there a term for that or is it just "conceptual art" as you mentioned above? — Thorongil

I think you are most concerned about the lack of representation in art more than anything. Seems to me you want you art to say something, to look like something, to show us something of the world, even if it is highly stylised. The sense I get from your posts here is: "If art is not trying to clearly show meaning, through representation built by the artist, what is the point? How can something without such work, such effort towards promoting and showing a standard of perfection, by worth anything at all?"

In this respect, the earlier comparison of your approach to art as similar to Kant is misplaced (as much as I agree with the idea Kant is a dry stick in the mud who sucks the life out of everything, and that such criticism could also be applied to abstract expressionism, it's the lack of stated perfection which you struggle with in non-representation art). You hate non-representation art precisely because of how is an anti-thesis of a Kantian approach. Non-representation art functions in a very immediate sense; it is not about displaying some obvious or clear representation through the painstaking work of the artist towards perfection, but rather living the moment of the artwork itself. It is a celebration of not seeking more than the immediate affect of a work.

Appreciating Duchamp's Urinal, for example, has nothing to do with a message it shows in representation. It's all about the beauty of the object itself (if one would call it that), of experiencing its shape and environmental position, and other meanings (e.g. what constitute "Art") which are associated with it but (critically) are not found in the representation of the work. It seems to me it is this (very anti-Kantian) lack of normative prescription which you despise about "modern art."

What is art meant to be saying? Non-representational art tends to say: "Nothing in particular. This art is not for demonstrating any valued state of "perfection" in representation. It isn't a showing of any sort of better life we are meant to aspire to. Everything is (for the given art work) already "perfect." Nothing needs to be changed or made better."

(it isn't a coincidence that our art criticism mirrors the philosophical shift away from the Nihilism of theism - "we need the perfection of God for life to be worthwhile"- to the idea of life being valuable in-itself- "What does my red and orange blotch need to say? Nothing. It is worthwhile just being its own thing).

As such, I don't think it is "modern," "conceptual" or even "abstract expressionism" which you despise (though works labeled as such may more frequently be non-representational in nature). Many works which fall into those categories have some sort of representation to them. It's the expanding of art from a painstakingly and laboriously constructed demonstration of what we should aspire to, to a more accessible moment which is wholly worthwhile in itself. -

Jamal

11.6kNote that Malevich, Kandinsky and others went abstract well before 1920.

Jamal

11.6kNote that Malevich, Kandinsky and others went abstract well before 1920.

Whatever one uses to call the predominant forms of "art" after about 1920 is what I am almost universally repelled by. Is there a term for that or is it just "conceptual art" as you mentioned above? — Thorongil

No, or only if it's actually conceptual art as I described, in which artistry is unimportant. This is certainly not the case with Rothko and Pollock. I think maybe you should rethink your 1920s cut-off. I'm not sure it corresponds to anything. You'd be better off identifying conceptual art, which you will say--and I will only very partially and mildly dispute--is wholly crap, and not even art; and distinguishing it from completely abstract painting and sculpture, which, though you can recognize a certain artistry, you just don't like.

They ought to have written books, then. — Thorongil

Yes, I agree. What they're doing is, I often feel, a bad way of doing philosophy as well as a bad way of doing art. -

Jamal

11.6kYou can paint a picture badly just as you can make a chair badly. Judgment takes a bit more effort though, because unlike bad chairs, there are no practical consequences, at least not in the relevant way. But I'm going to chicken out of answering more fully. It would be better as a separate discussion, so go ahead and create one if you feel like it.

Jamal

11.6kYou can paint a picture badly just as you can make a chair badly. Judgment takes a bit more effort though, because unlike bad chairs, there are no practical consequences, at least not in the relevant way. But I'm going to chicken out of answering more fully. It would be better as a separate discussion, so go ahead and create one if you feel like it. -

Thorongil

3.2kYou may be right, Willow. Thanks for the post. I do tend to think "non-representational art" is an oxymoron.

Thorongil

3.2kYou may be right, Willow. Thanks for the post. I do tend to think "non-representational art" is an oxymoron.

However, I don't agree with the following distinction:

Non-representation art functions in a very immediate sense; it is not about displaying some obvious or clear representation through the painstaking work of the artist towards perfection, but rather living the moment of the artwork itself. — TheWillowOfDarkness

I think representational art is immediate, in that it transports us into a timeless realm of Ideas. The particular scene on the canvas is a means of communicating something universal.

As a general comment, since jamalrob brought up my favorite cantankerous bachelor from Frankfurt, I would be willing to admit that what is called "conceptual art" (and literally everything) theoretically has the possibility to affect the aforementioned transportative experience, but all I'm saying is that it doesn't do this for me and that it is a mistake to call it art. -

Jamal

11.6kAs a general comment, since jamalrob brought up my favorite cantankerous bachelor from Frankfurt, I would be willing to admit that what is called "conceptual art" (and literally everything) theoretically has the possibility to affect the aforementioned transportative experience, but all I'm saying is that it doesn't do this for me and that it is a mistake to call it art. — Thorongil

Jamal

11.6kAs a general comment, since jamalrob brought up my favorite cantankerous bachelor from Frankfurt, I would be willing to admit that what is called "conceptual art" (and literally everything) theoretically has the possibility to affect the aforementioned transportative experience, but all I'm saying is that it doesn't do this for me and that it is a mistake to call it art. — Thorongil

Just a quick note to again emphasize that abstract painting and sculpture, including the examples in the OP, are not conceptual art and have very little in common with it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conceptual_art -

Mayor of Simpleton

661They ought to have written books, then. What they're doing is not art. But if they freely admit to being unskilled smartasses, then nothing more needs to be said. — Thorongil

Mayor of Simpleton

661They ought to have written books, then. What they're doing is not art. But if they freely admit to being unskilled smartasses, then nothing more needs to be said. — Thorongil

I'm curious...

... what exactly did the artist prior to this time do?

Did they (as I have sort of always supposed) try to 'communicate' via their art at all and if so... why didn't they simply write a book or just say what they had in mind rather than to go to all the trouble of making us sort of 'feel their intentions' via paint of a canvas?

Maybe I'm off here, but I would say that the reasons as to why the artists of the time you seem to detest painted and choose to 'communicate' as they did was that the past options of 'vocabulary' just did not fit what they wished to expressed in the context of the time in which they lived. In short... the 'vocabulary was old' and simply did not speak to their new ideas.

Instead of living in the stagnation of past rules and constraints to become a 'master of what indeed has been done many many time before' they chose the expand the vocabulary of art and chose to take a risk and pursue a new vocabulary that would question the very establishments they felt kept and maintained stagnation.

New techniques and new technical advances occurred resulting in an expanded vocabulary of art...

... exactly how is that bad?

Perhaps these unskilled smartasses were simply exposing the limitations and lack of continuation of creativity the establishment of smartasses had established as the standard of measure for all upon their own self-assumed authority?

I don't know... perhaps it would be good to inquire and who knows.... maybe they really aren't as much smartasses as one might assume?

Not all art is for everyone...

... I can live with that.

Can you?

At the moment, I'd assume you can't live with that, but I'll ask you first.

"They ought to have written books, then."

To be fair...

... any realist after the invention of the camera should have just take an photo and saved us the effort of bothering to look at their efforts of representation, eh?

Meow!

GREG -

_db

3.6kArt has become a commercial commodity instead of an exploration. It is now, more than ever (even the Renaissance), all about who can keep the attention of potential wealthy buyers. It doesn't even have to be "good" art. It just has to be attention-grabbing, different, unique, odd, or any other quality that sets it apart from other pieces. Now we have consultants that tell you which pieces of art were good, instead of judging the piece of art by how well it resonates with you.

_db

3.6kArt has become a commercial commodity instead of an exploration. It is now, more than ever (even the Renaissance), all about who can keep the attention of potential wealthy buyers. It doesn't even have to be "good" art. It just has to be attention-grabbing, different, unique, odd, or any other quality that sets it apart from other pieces. Now we have consultants that tell you which pieces of art were good, instead of judging the piece of art by how well it resonates with you.

Sometimes I enjoy modern art. But I can't stand it when someone tries to shove a stupid explanation behind it (the gray was chosen for its neutrality - bah), let me decide what I think it is about. I think the worst part about modern art is that it is impossible to tell the difference between an artist and a con artist, and you end up leaving the gallery wondering if you actually liked the piece or were influenced by a description below the piece. Or you leave the gallery wondering if you either hated the piece, or were just too skeptical to open up to the possibility that the artist was actually committed to doing art and not just money and fame.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Epistemology; Pure Abstract and Anchored Abstract

- The Problem of Universals, Abstract Objects, and Generalizations in Politics

- Abstract and concret objects

- Union of abstract metaphysical and personal anthropomorphic God concepts

- Is philosophical belief contingent to psychological causes and conditions or is it purely abstract?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum