-

Streetlight

9.1kThere are few ideas as regularly abused as 'laws of nature'. The source of this abuse stems from treating such laws as what are called 'covering laws': laws that cover each and every case of action, no matter how minute or detailed. Crudely put, the idea is that for everything that happens in nature, there is law or laws that corresponds to it. But laws of nature are not of this kind. In fact, no law at all is of this kind. Why? Because laws - natural or otherwise - are, at best, limits on action, they specify the bounds within which action takes place. While nothing can 'violate' the laws (this is what lends them their universality), there is no sense in which the laws are always applicable.

Streetlight

9.1kThere are few ideas as regularly abused as 'laws of nature'. The source of this abuse stems from treating such laws as what are called 'covering laws': laws that cover each and every case of action, no matter how minute or detailed. Crudely put, the idea is that for everything that happens in nature, there is law or laws that corresponds to it. But laws of nature are not of this kind. In fact, no law at all is of this kind. Why? Because laws - natural or otherwise - are, at best, limits on action, they specify the bounds within which action takes place. While nothing can 'violate' the laws (this is what lends them their universality), there is no sense in which the laws are always applicable.

The philosopher of science Nancy Cartwright explains this idea best: "Covering-law theorists tend to think that nature is well-regulated; in the extreme, that there is a law to cover every case. I do not. I imagine that natural objects are much like people in societies. Their behaviour is constrained by some specific laws and by a handful of general principles, but it is not determined in detail, even statistically. What happens on most occasions is dictated by no law at all.... God may have written just a few laws and grown tired." (Cartwright, How The Laws of Physics Lie).

The line in bold is worth emphasising: for the vast majority of action, the laws are simply silent: they neither specify anything positive nor negative. Bike riding laws for example, while universal in whichever state they apply, simply have nothing to say about spheres of action that have nothing to do with bike riding. The same is true of the 'laws of nature', which while universal and inviolable, are for the vast majority of phenomena simply inapplicable. The point here is to affirm the universality of laws of nature, while denying that they function as covering-laws.

One prominent field in which covering-law error is most apparent is in popular - and wrong - (mis)understandings of evolution, where is it often said that, for example, '(the laws of) natural selection govern all of evolution'. While it is true that nothing can violate natural selection (maladaptions will likely lead to extinction), it is also the case that most biological variation is 'adaptively neutral': there are variations - perhaps the majority of them - that are neither adaptive nor maladaptive, and to which natural selection remains 'blind'. Again, the point is that while natural selection is both universal and inviolable in biology, nothing about this universality or inviolability means that natural selections 'governs' each and every aspect of a species. Laws in this sense are more 'negative' than they are 'positive': they say what cannot be done, not 'determine' what can be; like natural selection, such laws are simply 'blind' to most of what happens in the universe.

--

It's also possible to deny that laws of nature have any place in science whatsoever, insofar as they might simply be considered as residues of theology [pdf], as Cartwright actually does, but I'm more interested in circumscribing the scope of such laws than denying them outright. -

Wayfarer

26.1kSo would you be inclined to agree that the below is an example of this kind of misunderstanding?

Wayfarer

26.1kSo would you be inclined to agree that the below is an example of this kind of misunderstanding?

One could argue that happiness has evolved into life as a survival mechanism. In a general sense, the things that make us happy revolve around concepts that are central to our survival. Essentially, that pleasure and pain are the only motivators of our species and they have evolved in ways that increase our chances of surviving. — MonfortS26

Because, if so, I perfectly agree with you. However, there are many threads, and many posts, that argue along these lines, with respect to how evolution does mandate, or at least favour, particular kinds of attributes or elements of human nature. In fact they’re writ large in a great deal of popular philosophy and evolutionary biology. -

Streetlight

9.1kIt could be an example of such an misunderstanding: the question after all is an empirical one - is there evidence to show that happiness evolved into life as a survival mechanism? And, even if there was, is there evidence to show that it remains a survival mechanism? It is well known that products of evolution - by whatever mechanism - have a knack of being coopted by other processes, for other ends than that which they were originally evolved for, which can in turn feed-back upon the evolution of that trait. Certainly, any a priori attribution of such and such a trait to survival and only survival is bad science through and through - which is to say, not a fault of the science, but of certain of its interpreters. And note that the way to correct this is through the science itself, not through anti-scientific screeds.

Streetlight

9.1kIt could be an example of such an misunderstanding: the question after all is an empirical one - is there evidence to show that happiness evolved into life as a survival mechanism? And, even if there was, is there evidence to show that it remains a survival mechanism? It is well known that products of evolution - by whatever mechanism - have a knack of being coopted by other processes, for other ends than that which they were originally evolved for, which can in turn feed-back upon the evolution of that trait. Certainly, any a priori attribution of such and such a trait to survival and only survival is bad science through and through - which is to say, not a fault of the science, but of certain of its interpreters. And note that the way to correct this is through the science itself, not through anti-scientific screeds. -

Wayfarer

26.1kFair enough. Although one wonders what kind of analysis might yield information that validates, or falsifies, the hypothesis that ‘the propensity for happiness is determined by evolutionary factors’.

Wayfarer

26.1kFair enough. Although one wonders what kind of analysis might yield information that validates, or falsifies, the hypothesis that ‘the propensity for happiness is determined by evolutionary factors’. -

T Clark

16.1kThere are few ideas as regularly abused as 'laws of nature'. — StreetlightX

T Clark

16.1kThere are few ideas as regularly abused as 'laws of nature'. — StreetlightX

First, of course, there are no "laws of nature." There are only general descriptions of how things behave.

The philosopher of science Nancy Cartwright explains this idea best: "Covering-law theorists tend to think that nature is well-regulated; in the extreme, that there is a law to cover every case. I do not. I imagine that natural objects are much like people in societies. Their behaviour is constrained by some specific laws and by a handful of general principles, but it is not determined in detail, even statistically. What happens on most occasions is dictated by no law at all." (Cartwright, How The Laws of Physics Lie). — StreetlightX

Wouldn't a materialist say that everything - from the behavior of subatomic particles, to consciousness, to the behavior of galaxies - is covered by, controlled by, the laws of physics? Even discounting that, can we say that, even though a particular phenomenon may not be controlled by a particular law of nature, everything is controlled by some law of nature? -

Streetlight

9.1kThere are only general descriptions of how things behave. — T Clark

Streetlight

9.1kThere are only general descriptions of how things behave. — T Clark

The curious thing about the laws is that they are almost entirely undescriptive. In fact, one of the most interesting things that Cartwirght demonstrates is that there is an inverse relation to how true a law is, and how much explanatory power it has. Her discussion of this point is worth quoting at length:

"The laws of physics do not provide true descriptions of reality. ... [Consider] the the law of universal gravitation [F=Gmm′/r^2] ... Does this law truly describe how bodies behave? Assuredly not. It is not true that for any two bodies the force between them is given by the law of gravitation. Some bodies are charged bodies, and the force between them is not Gmm′/r^2. For bodies which are both massive and charged, the law of universal gravitation and Coulomb's law (the law that gives the force between two charges) interact to determine the final force. But neither law by itself truly describes how the bodies behave. No charged objects will behave just as the law of universal gravitation says; and any massive objects will constitute a counterexample to Coulomb's law.

These two laws are not true; worse, they are not even approximately true. In the interaction between the electrons and the protons of an atom, for example, the Coulomb effect swamps the gravitational one, and the force that actually occurs is very different from that described by the law of gravity. There is an obvious rejoinder: I have not given a complete statement of these two laws, only a shorthand version. [There ought to be] an implicit ceteris paribus ('all things equal') modifier in front, which I have suppressed. Speaking more carefully ... If there are no forces other than gravitational forces at work, then two bodies exert a force between each other which varies inversely as the square of the distance between them, and varies directly as the product of their masses

I will allow that this law is a true law, or at least one that is held true within a given theory. But it is not a very useful law. One of the chief jobs of the law of gravity is to help explain the forces that objects experience in various complex circumstances. This law can explain in only very simple, or ideal, circumstances. It can account for why the force is as it is when just gravity is at work; but it is of no help for cases in which both gravity and electricity matter. Once the ceteris paribus modifier has been attached, the law of gravity is irrelevant to the more complex and interesting situations." (How the Laws of Physics Lie.

Wouldn't a materialist say that everything - from the behavior of subatomic particles, to consciousness, to the behavior of galaxies - is covered by, controlled by, the laws of physics? — T Clark

A vulgar, unreflective materialism, maybe. But I can imagine few things more theologically charged than the idea that 'there is a law that covers everything'; Materialism ought to - and can do - better than such vulgarities. The physicist Paul Davis writes nicely on this: "The very notion of physical law has its origins in theology. The idea of absolute, universal, perfect, immutable laws comes straight out of monotheism, which was the dominant influence in Europe at the time science as we know it was being formulated by Isaac Newton and his contemporaries. Just as classical Christianity presents God as upholding the natural order from beyond the universe, so physicists envisage their laws as inhabiting an abstract transcendent realm of perfect mathematical relationships. Furthermore, Christians believe the world depends utterly on God for its existence, while the converse is not the case. Correspondingly, physicists declare that the universe is governed by eternal laws, but the laws remain impervious to events in the universe. I think this entire line of reasoning is now outdated and simplistic".

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2007/jun/26/spaceexploration.comment

The paper I mentioned and linked to in the OP at the end by Cartwright ("No Gods, No Laws") similarly makes the case that physical laws can only make sense with the invocation of a God, which is all the more reason to treat physical laws with extreme prejudice. -

T Clark

16.1kThe laws of physics do not provide true descriptions of reality. ... [Consider] the the law of universal gravitation [F=Gmm′/r^2] ... Does this law truly describe how bodies behave? Assuredly not. It is not true that for any two bodies the force between them is given by the law of gravitation. — StreetlightX

T Clark

16.1kThe laws of physics do not provide true descriptions of reality. ... [Consider] the the law of universal gravitation [F=Gmm′/r^2] ... Does this law truly describe how bodies behave? Assuredly not. It is not true that for any two bodies the force between them is given by the law of gravitation. — StreetlightX

Boy, this, along with the rest of the quoted text, is really wrong, or at least trivially correct. A quibble about language. As I implied in the first line of my post, I don't find the idea of a law of nature a very useful one, and I agree it's misleading, but once we've decided to discuss things in those terms, I, and most other people with an interest in science, have no problem applying the concept. Come on - just because the law of universal gravitation doesn't necessarily describe all the forces on a massive object, doesn't mean it doesn't tell us something important about how matter behaves. I'm guessing you disagree. Please explain. -

Jamal

11.7kJust on the subject of descriptiveness (and sorry if I'm inappropriately fisking here)...

Jamal

11.7kJust on the subject of descriptiveness (and sorry if I'm inappropriately fisking here)...

It can account for why the force is as it is when just gravity is at work; but it is of no help for cases in which both gravity and electricity matter — Cartwright

Didn't she already supply the solution here:

For bodies which are both massive and charged, the law of universal gravitation and Coulomb's law (the law that gives the force between two charges) interact to determine the final force — Cartwright

That is, the laws of physics together describe how things behave. Which means that this is wrong:

Once the ceteris paribus modifier has been attached, the law of gravity is irrelevant to the more complex and interesting situations — StreetlightX

Surely we can, and do, apply multiple laws? -

Streetlight

9.1kCome on - just because the law of universal gravitation doesn't necessarily describe all the forces on a massive object, doesn't mean it doesn't tell us something important about how matter behaves. I'm guessing you disagree. — T Clark

Streetlight

9.1kCome on - just because the law of universal gravitation doesn't necessarily describe all the forces on a massive object, doesn't mean it doesn't tell us something important about how matter behaves. I'm guessing you disagree. — T Clark

There's not really much to disagree - or agree - with though. "Tells us something important". Sure, Ok, as far as a vague 'something important' goes. -

T Clark

16.1k"Tells us something important". Sure, Ok, as far as a vague 'something important' goes. — StreetlightX

T Clark

16.1k"Tells us something important". Sure, Ok, as far as a vague 'something important' goes. — StreetlightX

How is the something important that the law of universal gravitation describes vague? Two bodies with the property we call "mass" tend to move towards each other in a regular way which can be quantified, whether we describe that tendency as a force or a bending of space-time. -

Wayfarer

26.1kCertainly, anya priori attribution of such and such a trait to survival and only survival is bad science through and through - which is to say, not a fault of the science, but of certain of its interpreters. And note that the way to correct this is through the science itself, not through anti-scientific screeds. — StreetlightX

Wayfarer

26.1kCertainly, anya priori attribution of such and such a trait to survival and only survival is bad science through and through - which is to say, not a fault of the science, but of certain of its interpreters. And note that the way to correct this is through the science itself, not through anti-scientific screeds. — StreetlightX

What prompted this thread was one of my frequent criticisms of what I refer to as 'Darwinian rationalism' - that is on of the 'anti-science screed' you're referring to. And what I said to prompt it was a remark about how evolutionary theory tends to rationalise every human attribute in terms of 'what enhances survival'. You see posts all the time about this - the one I quoted was an example, but there are countless more. And it's because it's the 'scientific' way of understanding human nature, right? None of this religious nonsense - we're for Scientific Facts. So let's not try and drag it into abstruse metaphysics.

Actually one of the better commentators on this is the very prim and proper English philosopher, Mary Midgley - a personal favourite of Dawkins! - whose book Evolution as a Religion lays it out rather nicely. Helped by the fact that she is at least a 'non-theist', at least certainly has no ID ax to grind. She just knows scientistic nonsense when she sees it, and she sees a lot of it in pop darwinian philosophizing, which is endemic in the Academy nowadays. -

Streetlight

9.1kSurely we can, and do, apply multiple laws? — jamalrob

Streetlight

9.1kSurely we can, and do, apply multiple laws? — jamalrob

Heh, I was waiting for this rejoinder, but didn't want to drop an even bigger quote than I did, because this is exactly what she addresses in the section right after (sorry for the long quote but it's just easier this way and I'm lazy):

"The vector addition story is, I admit, a nice one. But it is just a metaphor. We add forces (or the numbers that represent forces) when we do calculations. Nature does not ‘add’ forces. ... [On the vector addition account], Coulomb's law and the law of gravity come out true because they correctly describe what influences are produced—here, the force due to gravity and the force due to electricity. The vector addition law then combines the separate influences to predict what motions will occur. This seems to me to be a plausible account of how a lot of causal explanation is structured. But as a defence of the truth of fundamental laws, it has two important drawbacks.

First, in many cases there are no general laws of interaction. Dynamics, with its vector addition law, is quite special in this respect. This is not to say that there are no truths about how this specific kind of cause combines with that, but rather that theories can seldom specify a procedure that works from one case to another. Without that, the collection of fundamental laws loses the generality of application which [vector addition] hopes to secure.

In practice engineers handle irreversible processes with old fashioned phenomenological laws describing the flow (or flux) of the quantity under study. Most of these laws have been known for quite a long time. For example there is Fick's law... Equally simple laws describe other processes: Fourier's law for heat flow, Newton's law for sheering force (momentum flux) and Ohm's law for electric current. Each of these is a linear differential equation in t, giving the time rate of change of the desired quantity (in the case of Fick's law, the mass). Hence a solution at one time completely determines the quantity at any other time. Given that the quantity can be controlled at some point in a process, these equations should be perfect for determining the future evolution of the process. They are not.

The trouble is that each equation is a ceteris paribus law. It describes the flux only so long as just one kind of cause is operating. [Vector addition] if it works, buys facticity, but it is of little benefit to (law) realists who believe that the phenomena of nature flow from a small number of abstract, fundamental laws. The fundamental laws will be severely limited in scope. Where the laws of action go case by case and do not fit a general scheme, basic laws of influence, like Coulomb's law and the law of gravity, may give true accounts of the influences that are produced; but the work of describing what the influences do, and what behaviour results, will be done by the variety of complex and ill-organized laws of action." -

Streetlight

9.1kTwo bodies with the property we call "mass" tend to move towards each other in a regular way which can be quantified, — T Clark

Streetlight

9.1kTwo bodies with the property we call "mass" tend to move towards each other in a regular way which can be quantified, — T Clark

But the point is they don't, except in highly idealised situations, 'do so in a regular way that can be quantified'. Your statement is literally untrue for all but a very, very small number of situations, and situations almost definitely artificial at that. -

Streetlight

9.1kAnd it's because it's the 'scientific' way of understanding human nature, right? — Wayfarer

Streetlight

9.1kAnd it's because it's the 'scientific' way of understanding human nature, right? — Wayfarer

But it is not the scientific way of understanding nature. That's the point. You'd like it to be the 'scientific way' of understanding nature, because it provides more fuel for your anti-science proclivities. But so much the worse for those proclivities - and the pseudo-science it militates against. A pox on both houses. -

Jamal

11.7k[Vector addition] if it works, buys facticity, but it is of little benefit to (law) realists who believe that the phenomena of nature flow from a small number of abstract, fundamental laws. — Cartwright

Jamal

11.7k[Vector addition] if it works, buys facticity, but it is of little benefit to (law) realists who believe that the phenomena of nature flow from a small number of abstract, fundamental laws. — Cartwright

I guess I was thinking that facticity--which the laws give us, or can give us--does amount to descriptiveness, even if they don't amount to the metaphysical grounding that the law realists claim for them. -

Streetlight

9.1kYeah, it's a careful line to tread. Cartwright's position - which makes alot of sense to me, is anti-realism about laws, but realism about (scientific) entities. The case for entity realism is perhaps another topic in itself, but as far as the status of laws goes, their usefulness is, on her account, largely epistemic: "I think that the basic laws and equations of our fundamental theories organise and classify our knowledge in an elegant and efficient manner, a manner that allows us to make very precise calculations and predictions. The great explanatory and predictive powers of our theories lies in their fundamental laws. Nevertheless the content of our scientific knowledge is expressed in the phenomenological laws" [which differ from 'fundamental laws', in their being context specific - SX].

Streetlight

9.1kYeah, it's a careful line to tread. Cartwright's position - which makes alot of sense to me, is anti-realism about laws, but realism about (scientific) entities. The case for entity realism is perhaps another topic in itself, but as far as the status of laws goes, their usefulness is, on her account, largely epistemic: "I think that the basic laws and equations of our fundamental theories organise and classify our knowledge in an elegant and efficient manner, a manner that allows us to make very precise calculations and predictions. The great explanatory and predictive powers of our theories lies in their fundamental laws. Nevertheless the content of our scientific knowledge is expressed in the phenomenological laws" [which differ from 'fundamental laws', in their being context specific - SX].

She comes close to the famous scientific anti-realism of Bas van Fraassen, who is an anti-realist about entities, precisely because he believes that it's all just a case of organising and classifying our knowledge. But Cartwright's point is that if you pay attention to the peculiar status of laws, one can admit this without being an anti-realist about entities. @Banno put it once nicely in a post long ago - something like: the point of scientific equations is to add up nicely. It struck me as barbarous at the time, but I've come to see it as making a great deal of sense. -

fdrake

7.2kThere are things about force as a concept -as a real abstraction- which make it highly amenable to analysis with vectors. Fundamentally, this comes down to motion having a direction as well as a magnitude. A vector just is a quantity with a direction and a magnitude, and a force describes a propensity to shunt with a given strength in a given direction - the same is true of the more abstract force fields which ascribe a strength of movement and a direction to points in space.

fdrake

7.2kThere are things about force as a concept -as a real abstraction- which make it highly amenable to analysis with vectors. Fundamentally, this comes down to motion having a direction as well as a magnitude. A vector just is a quantity with a direction and a magnitude, and a force describes a propensity to shunt with a given strength in a given direction - the same is true of the more abstract force fields which ascribe a strength of movement and a direction to points in space.

If changes in motion are equivalent to changes in direction and changes in a magnitude, is it then surprising that a mathematical language that allows us to relate changes in direction and changes in magnitude to other changes in direction and changes in magnitude allows for the description of motions in general?

Forces enter the picture as what drives changes in motion. This is a restatement of Newton's first law.

Forces add as vectors - changes in direction and changes in magnitude interact together as vector changes - this is essentially Newton's second law - multiply the changes induced in motion by vectors (see law 1) by the mass of the changing thing (or the mass as a function of time, or the mass as a function of momentum and energy) and you get the full statement of it.

Newton's third law is what interprets forces as body-body interactions, specifically a force projecting from A to B induces/is equivalent (in magnitude but opposite direction) from a force projecting from B to A. This is the same as saying that the relative position vector from A to B, is equal to

Newton's laws aren't just formal predictive apparatuses like (most) statistical models, they're based on physical understanding. They aren't just mathematical abstractions either, the use of mathematics in physics is constrained by (as physicists put it) 'physical meaning'.

The mathematics doesn't care that the Coulomb Force law (alone) predicts that electrons spiral towards nuclei. The physics does. -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Laws are models of the way things are. If there are limits in the laws, then that is a representation of the limits in nature.Because laws - natural or otherwise - are, at best, limits on action, they specify the bounds within which action takes place. While nothing can 'violate' the laws (this is what lends them their universality), there is no sense in which the laws are always applicable. — StreetlightX

So people don't have any reason for what they do outside of some specific laws and a handful of general principles? Nonsense.The philosopher of science Nancy Cartwright explains this idea best: "Covering-law theorists tend to think that nature is well-regulated; in the extreme, that there is a law to cover every case. I do not. I imagine that natural objects are much like people in societies. Their behaviour is constrained by some specific laws and by a handful of general principles, but it is not determined in detail, even statistically. What happens on most occasions is dictated by no law at all.... God may have written just a few laws and grown tired." (Cartwright, How The Laws of Physics Lie). — StreetlightX

Their behavior is constrained by the shape and size of their body and the scope of their memory. What happens in every occasion is dictated by the causes that came before any said occasion. We just haven't explained every natural causal force and its related effect - so it can seem like there aren't any laws for certain occasions. We just haven't gotten around to explaining every causal relationship. Be patient. -

ssu

9.8kI would say that we use models to understand reality usually for some purpose. And some models appear to be so obvious and are so useful that we define them as to be laws.

ssu

9.8kI would say that we use models to understand reality usually for some purpose. And some models appear to be so obvious and are so useful that we define them as to be laws.

Of course these laws just abide to their context. Newtonian physics works just fine for nearly all questions, but not for everything, and hence we have to have things like relativity.

Now could our understanding change from the present? Of course! Some even more neat and useful theory could replace the existing ones, but it likely wouldn't be proving the earlier "laws" false or erroneous, but that the earlier theories said to be laws haven't covered everything and that there's simply a different point of view. -

Rich

3.2kBecause laws - natural or otherwise - are, at best, limits on action, they specify the bounds within which action takes place. — StreetlightX

Rich

3.2kBecause laws - natural or otherwise - are, at best, limits on action, they specify the bounds within which action takes place. — StreetlightX

Really? No way, unless infinity is considered a boundary.The same is true of the 'laws of nature', which while universal and inviolable, — StreetlightX

And you know this how?'. While it is true that nothing can violate natural selection (maladaptions will likely lead to extinction), — StreetlightX

And the proof is?Again, the point is that while natural selection is both universal and inviolable in biology, nothing about this universality or inviolability means that natural selections 'governs' each and every aspect of a species. — StreetlightX

I guess this means that the universal and inviolable can be violated?

It seems that the Laws of Nature is completely fabricated. They are just sweeping statements that are thrown around to justify some particular point of view. There is zero evidence of any sort that there are any laws governing the completely unpredictable behavior of life, yet science loves to extend some simple models of matter to the behavior of life. -

T Clark

16.1kI guess this means that the universal and inviolable can be violated?

T Clark

16.1kI guess this means that the universal and inviolable can be violated?

It seems that the Laws of Nature is completely fabricated. They are just sweeping statements that are thrown around to justify some particular point of view. There is zero evidence of any sort that there are any laws governing the completely unpredictable behavior of life, yet science loves to extend some simple models of matter to the behavior of life. — Rich

So, in addition to denying the validity of quantum mechanics and relativity, you also deny the validity of Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection. Is that correct? Do you also deny the fact of evolution, whatever the mechanism? Do you believe that all life on earth shares a common genetic heritage because all of it, all of us, share a common ancestor? -

T Clark

16.1k"The vector addition story is, I admit, a nice one. But it is just a metaphor. We add forces (or the numbers that represent forces) when we do calculations. Nature does not ‘add’ forces. ... — StreetlightX

T Clark

16.1k"The vector addition story is, I admit, a nice one. But it is just a metaphor. We add forces (or the numbers that represent forces) when we do calculations. Nature does not ‘add’ forces. ... — StreetlightX

All scientific generalization and abstraction, all generalization and abstraction of any kind, is "just a metaphor." Except at the most simplistic level, humans interact with the universe through metaphor.

In practice engineers handle irreversible processes with old fashioned phenomenological laws describing the flow (or flux) of the quantity under study. — StreetlightX

Can you explain what you mean by "phenomenological laws." I looked it up online and the only reference was Cartwright. Does it just mean more concrete, more restricted to a smaller set of phenomena than a universal law? More empirical, ad hoc? Is that what you mean by:

...the laws of action go case by case and do not fit a general scheme, — StreetlightX

The trouble is that each equation is a ceteris paribus law. It describes the flux only so long as just one kind of cause is operating. [Vector addition] if it works, buys facticity, but it is of little benefit to (law) realists who believe that the phenomena of nature flow from a small number of abstract, fundamental laws. — StreetlightX

Is that a bad thing? We have a tool box full of laws we bring out when we need them. That's basically what engineers do all the time. Or is that what you've been saying? Are there really "law realists" who don't acknowledge the day-to-dayness of the scientific process, even at a practical level? If that's what we're talking about, maybe we don't have a disagreement. Or maybe we still do. I'll think about it.

Final question - is the way I've responded to your post Fisking? Is that a problem? -

Streetlight

9.1kI would say that we use models to understand reality usually for some purpose. And some models appear to be so obvious and are so useful that we define them as to be laws. — ssu

Streetlight

9.1kI would say that we use models to understand reality usually for some purpose. And some models appear to be so obvious and are so useful that we define them as to be laws. — ssu

I largely agree with this, as does Cartwright, for whom fundamental laws are indeed useful as explanatory tools, with the caveat that their explanatory power does not imply their truth, where truth is simply understood in the naive sense of corresponding to the facts of a phenomenon (what she refers to as their 'facticity'). Again the simple idea is that for the most part, F=Gmm′/r^2 - for example - simply is untrue as a description for almost all but a very small set of artificial behaviour.

To crystallize debate, perhaps a simple yes and no question can be asked: do fundamental laws provide accurate, true descriptions of most physical phenomena? It seems to me that the straightforward answer is no. And not even because of issues like Newtonian physics not taking into account quantum physics: on its own terms Netownian mechanics do not accurately describe phenomena. F=ma is almost universally untrue for any moving body one might care to measure in the real world. Which is again not to detract from it's explanatory power. -

schopenhauer1

11kBecause, if so, I perfectly agree with you. However, there are many threads, and many posts, that argue along these lines, with respect to how evolution does mandate, or at least favour, particular kinds of attributes or elements of human nature. In fact they’re writ large in a great deal of popular philosophy and evolutionary biology. — Wayfarer

schopenhauer1

11kBecause, if so, I perfectly agree with you. However, there are many threads, and many posts, that argue along these lines, with respect to how evolution does mandate, or at least favour, particular kinds of attributes or elements of human nature. In fact they’re writ large in a great deal of popular philosophy and evolutionary biology. — Wayfarer

Agreed. I was trying to argue against the overreach of natural selection/instinct on all human behavior for example in a couple threads. -

Moliere

6.5kShe comes close to the famous scientific anti-realism of Bas van Fraassen, who is an anti-realist about entities, precisely because he believes that it's all just a case of organising and classifying our knowledge. But Cartwright's point is that if you pay attention to the peculiar status of laws, one can admit this without being an anti-realist about entities. — StreetlightX

Moliere

6.5kShe comes close to the famous scientific anti-realism of Bas van Fraassen, who is an anti-realist about entities, precisely because he believes that it's all just a case of organising and classifying our knowledge. But Cartwright's point is that if you pay attention to the peculiar status of laws, one can admit this without being an anti-realist about entities. — StreetlightX

Interesting thread!

How would you differentiate entities from theories?

I ask because, as an old hack of a chemist, it seems that positing entities were part and parcel to theory.

Also, how would this analysis fair when considering thermodynamics? I have in mind the 2nd law, in particular. It's extremely abstract, but doesn't really deal with entities as much (as I understand it), but does seem quite universal ((edit: I should use your terminology better. Not universal, but rather a cover-law)) in that it's often linked to the arrow of time. -

Streetlight

9.1kAll scientific generalization and abstraction, all generalization and abstraction of any kind, is "just a metaphor." Except at the most simplistic level, humans interact with the universe through metaphor. — T Clark

Streetlight

9.1kAll scientific generalization and abstraction, all generalization and abstraction of any kind, is "just a metaphor." Except at the most simplistic level, humans interact with the universe through metaphor. — T Clark

I disagree. Scientific modelling is a very specific process in which a system of inferences available in a formal system (the model) can be made to/ought to match the system of causal relations in a natural system. Cf. Robert Rosen's modelling relation:

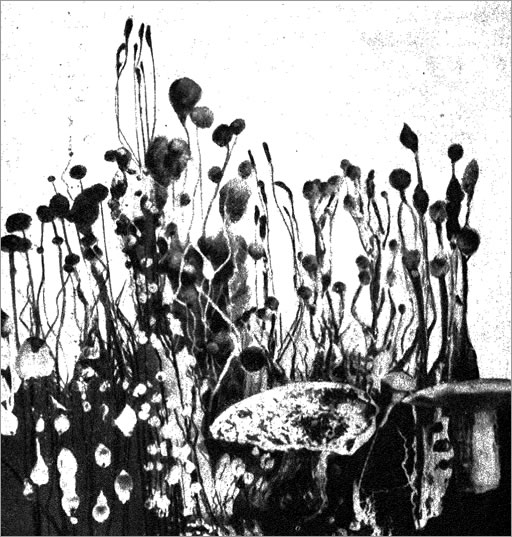

Note that Rosen distinguishes a model from a simulation: whereas a model specifically aims to redouble causal relations by means of formal entailments, a simulation does not (the entailment relations in a simulation are a 'black box', one simply tinkers with the knobs until the simulation 'looks right'). Conway's 'game of life' would be one such example of a simulation. Or else something like Stéphane Leduc's famous 'models' of life (created using some clever chemistry) which look and sometimes even act like living things, are also mere simulations, and not models of life, and they are simulations because they do not replicate the causal relations involved in living things. Their 'parameters of change' are entirely different. An example of Ludec's work (which was a scientific bombshell when he published, although his name is forgotten today):

(Evelyn Fox Keller describes Leduc's work: "by employing a variety of metallic salts and alkaline silicates (for example, ferrocyanide of copper, potash, and sodium phosphate) and adjusting their proportions and the stage of “growth” at which they were added, Leduc was able to produce a number of spectacular effects—inorganic structures exhibiting a quite dramatic similitude to the growth and form of ordinary vegetable and marine life . By “appropriate means,” it proved possible to produce “terminal organs resembling flowers and seed-capsules,” “corral-like forms,” and “remarkable fungus-like forms.” (Fox-Keller, Making Sense of Life)

Rosen has a more mathematically rigorous way to distinguish between models and simulations, but the gist is conveyed I hope. The larger point is that to call scientific modelling a 'metaphor' severely understates what is involved in modelling, with metaphors being more akin to simulations.

Can you explain what you mean by "phenomenological laws." — T Clark

A quick example from Cartwright because I've written too much already: "Francis Everitt, a distinguished experimental physicist and biographer of James Clerk Maxwell, picks Airy's law of Faraday's magneto-optical effect as a characteristic phenomenological law. In a paper with Ian Hacking, he reports, ‘Faraday had no mathematical theory of the effect, but in 1846 George Biddell Airy (1801–92), the English Astronomer Royal, pointed out that it could be represented analytically in the wave theory of light by adding to the wave equations, which contain second derivatives of the displacement with respect to time, other ad hoc terms, either first or third derivatives of the displacement.’ Everitt and Hacking contrast Airy's law with other levels of theoretical statement—‘physical models based on mechanical hypotheses,... formal analysis within electromagnetic theory based on symmetry arguments’, and finally, ‘a physical explanation in terms of electron theory’ given by Lorentz, which is ‘essentially the theory we accept today’.

Everitt distinguishes Airy's phenomenological law from the later theoretical treatment of Lorentz, not because Lorentz employs the unobservable electron, but rather because the electron theory explains the magneto-optical effect and Airy's does not. Phenomenological laws describe what happens. They describe what happens in superfluids or meson-nucleon scattering as well as the more readily observed changes in Faraday's dense borosilicate glass, where magnetic fields rotate the plane of polarization"; [ Example of Airy modelling ]

The point of the distinction being that "In modern physics, and I think in other exact sciences as well, phenomenological laws are meant to describe, and they often succeed reasonably well. But fundamental equations are meant to explain, and paradoxically enough the cost of explanatory power is descriptive adequacy. Really powerful explanatory laws of the sort found in theoretical physics do not state the truth." -

MonfortS26

256Although one wonders what kind of analysis might yield information that validates, or falsifies, the hypothesis that ‘the propensity for happiness is determined by evolutionary factors’. — Wayfarer

MonfortS26

256Although one wonders what kind of analysis might yield information that validates, or falsifies, the hypothesis that ‘the propensity for happiness is determined by evolutionary factors’. — Wayfarer

If you view it from the perspective of psychological hedonism, that all motivation is dictated by pain and pleasure, then even if there is an amount of neutral selection in what makes humans happy there still have to be positive and negative traits associated with that motivation as well. Psychological hedonism is definitely falsifiable and if it is true, the only place those motivations can come from is evolution. -

T Clark

16.1kThe point of the distinction being that "In modern physics, and I think in other exact sciences as well, phenomenological laws are meant to describe, and they often succeed reasonably well. But fundamental equations are meant to explain, and paradoxically enough the cost of explanatory power is descriptive adequacy. Really powerful explanatory laws of the sort found in theoretical physics do not state the truth." — StreetlightX

T Clark

16.1kThe point of the distinction being that "In modern physics, and I think in other exact sciences as well, phenomenological laws are meant to describe, and they often succeed reasonably well. But fundamental equations are meant to explain, and paradoxically enough the cost of explanatory power is descriptive adequacy. Really powerful explanatory laws of the sort found in theoretical physics do not state the truth." — StreetlightX

Very helpful, interesting post. This whole thread is interesting and makes me ask myself questions I hadn't before. I like and think I understand the distinction between models and simulations. As for metaphors, I disagree, but we can save that for another discussion. I will say - I think models are metaphors while simulations probably aren't. -

apokrisis

7.8kReally powerful explanatory laws of the sort found in theoretical physics do not state the truth." — Cartwright

apokrisis

7.8kReally powerful explanatory laws of the sort found in theoretical physics do not state the truth." — Cartwright

Fundamental laws abstract away all initial conditions. They are absolutely general because they carry no history and you get to plug that into the equations as some set of measurements.

Cartwright is making the point that laws are descriptions of constraints. They describe the physical context that impinges on material locales to give them shape as objects or events. And every material locale may have a complex history. The past will have built up a lot of surrounding information in the neighbouring environment which bears causally on what happens next.

A ball will run down a slope. That is a fairly simple example of a set of initial conditions. You could have a law of nature that describes this single situation. The law describes a certain ball, a certain slope, and a certain outcome that must always be seen if the situation is repeated. So the law is absolutely specific, but overloaded with that specificity. It is full of initial conditions descriptions. Physics wants to abstract away everything that is particular about this situation and simply have general laws of motion and gravity - the universal constraints on events - and let you then plug in all the locally special information about some specific history, some specific set of material constraints. Like the locations and characteristics of some ball, some slope.

So every event or object is embedded in a structure of causal relations. The whole thing has a history that individuated it. We then come along and analyse that using our dichotomy of model and measurement. We separate what is going on into general laws or the universe’s most general constraints, and initial conditions, or the universe’s most individual and particular constraints. Some ball and slope is understood as being general in having to be ruled by Newtonian laws, and particular in having their own angles and weights.

However Cartwright is getting carried away in saying the big laws don’t tell truths. That is philosophy of science rhetoric to get her distinctive position noticed.

But then neither is she the first to realise that this is how the “laws of nature” work.

The actual world is the sedimentation of all the symmetry breakings that create some actual state of history. We then need to unwind that context of constraints that impinges to individuate every material locale by making our rather artificial distinction between the most general possible universal rules and the most particular possible locally measured qualities.

The ideal physical theory is an equation that describes a universal symmetry in a state of brokenness - so like, E = mc^2. Then we go measure the particular mass, or energy, to see how it this constraint would relate it.

And to measure the mass of an object or event becomes a further story of constraints. We have to confine or isolate the supposed individual thing somehow. We have to decide when the measurement is accurate enough to give us all the information.

It is constraints all the way down. And measurement becomes an informal art, a matter of judgement and experience we learn to apply to individual cases. The human modeller with his abstracts laws has to re-enter the picture as a constructor or the constraints that fix the initial conditions.

This is where things get tricky in quantum mechanics, nonlinear mechanics, and anything dealing with emergent properties. -

Streetlight

9.1kA word on truth: I've been somewhat carried away by the discussion on truth even through the OP wasn't about the truth of the fundamendal laws as such. Nonetheless: I think one can grant Cartwright's point - that the laws in general are 'untrue' in the vast majority of cases - without for all that claiming that the laws themselves are 'false'. At stake basically are two different language games, one in which truth is indexed to descriptive veracity (Cartwright's), and another in which truth is indexed to contingency, or being-otherwise.

Streetlight

9.1kA word on truth: I've been somewhat carried away by the discussion on truth even through the OP wasn't about the truth of the fundamendal laws as such. Nonetheless: I think one can grant Cartwright's point - that the laws in general are 'untrue' in the vast majority of cases - without for all that claiming that the laws themselves are 'false'. At stake basically are two different language games, one in which truth is indexed to descriptive veracity (Cartwright's), and another in which truth is indexed to contingency, or being-otherwise.

In the second sense of truth is basically this: are the laws otherwise than what we have discovered? The answer is no. It is true that F=ma, and not F=ma^2. On the other hand, it is not true that F=ma accurately and precisely describes the bahaviour of most moving bodies. These senses of truth are not in contradiction, because they bear on different domains, or rather, they attempt to respond to different questions (It is an accurate description vs. Is the law otherwise than stated?). The strangeness and unease which might accompany Cartwright's insistence on the 'untruth' of the laws stems from conflating - in a way Cartwright does not - these two uses of truth.

There's a point to be made about how this very nicely captures a Wittgenstienian take on truth - in which truth is what we do with it - but that's perhaps for another thread. -

apokrisis

7.8kNonetheless: I think one can grant Cartwright's point - that the laws in general are 'untrue' in the vast majority of cases - without for all that claiming that the laws themselves are 'false'. — StreetlightX

apokrisis

7.8kNonetheless: I think one can grant Cartwright's point - that the laws in general are 'untrue' in the vast majority of cases - without for all that claiming that the laws themselves are 'false'. — StreetlightX

Still an attention getting move more than a reasonable stance. But then outside of philosophy of science, many might think science tells the transcendent truths of reality.

It's a difficult one. :)

In the second sense of truth is basically this: are the laws otherwise than what we have discovered? The answer is no. It is true that F=ma, and not F=ma^2. On the other hand, it is not true that F=ma accurately and precisely describes the bahaviour of most moving bodies. These senses of truth are not in contradiction, because they bear on different domains, or rather, they attempt to respond to different questions (It is an accurate description vs. Is the law otherwise than stated?). The strangeness and unease which might accompany Cartwright's insistence on the 'untruth' of the laws stems from conflating - in a way Cartwright does not - these two uses of truth. — StreetlightX

I don't think that is it at all.

The point - as you said - is that laws are simply descriptions of prevailing constraints. They don't need to be exception-less. Indeed, if reality itself is inherently probabilistic at a fundamental level, then they couldn't be. The laws themselves could only capture the strong probabilities of a Universe that has been around long enough to develop a history of well-regulated habit.

So a law like F=ma is a limit state expression. In an ideal world with nothing to individuate the circumstance, it would apply. But every actual situation is a mess of some particular local history. There are all sorts of other causal influences that could impact on the behaviour of things - create the apparent exceptions.

Newton's laws of course themselves presumed an already constrained world - one that was geometrically flat and where energy scale did not affect the picture. New even more abstract laws were framed to allow the Newtonian cosmos to be viewed as now the special case - flat rather than curved, with its tendency to fluctuations suppressed by it having become so classically cold and expanded.

So the truth-telling is about a hierarchy of constraints. What it gets right is how much of the backdrop that gets taken for granted as the frame of reference is itself turned into a model with fewer constraints and so a need for more symmetry-breaking measurements.

Science is an art that balances the two kinds of information - the modelling and the measuring, the laws and the initial conditions. There is no truth to be discovered so much as that we have to make some pragmatic trade-off which works.

So I disagree with your account in this regard. What you are saying amounts to having to decide if an "accurate description" is to be found in the theory or its measurements? Clearly, the accuracy is a combination of some appropriate level of trade-off. It is how the two work together in practice. This is what needs to be emphasised.

Both cost us an effort. We want to strike the balance that describes the world with the least information. And while you can write F=ma on a t-shirt, do you want to have to measure the state of every individual particle to know what is going on in a complex system?

So "untruth" is really only ever "unefficiency". Even a really bad theory could be acceptable if we are willing to treat every exception as something to be individually explained by some excuse. That's how religion deals with the irregularity of miracles, or psychics with the erratic nature of their forecasts.

In other words, this harking on about truth or veracity shows the grip of another age. We should be more use to pragmatism by now. However that in turn - in being based on a hierarchically-organised constraints-based logic - stands against certain other philosophical leanings.

It is just as wrong to say laws are merely convenient descriptions as to say they are actual truths. That way lies an argument for strong social constructionism.

Pragmatism has to stand in the tricky space between these two extremes. Laws may be just descriptions, but they are also optimal in some way that actually reflects the hierarchical and constraints-based facts of the world. The structure of existence is out there. The exceptionality of nature is being suppressed by its own accumulating history. And science - as an epistemic structure - works best when it adopts the same logic.

There's a point to be made about how this very nicely captures a Wittgenstienian take on truth - in which truth is what we do with it - but that's perhaps for another thread. — StreetlightX

Exactly what I fear. All this is slanted towards the support of strong PoMo relativism. Out goes the baby with the bathwater as usual.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum