-

Moliere

6.5kThe thought experiment using the deck of cards, is firstly about the order of the deck of cards. When one observes something that seems ordered, and given options as to how such order came to happen between design and randomness most would view design more likely. FTA proposes the that the universe is ordered for embodied, sentient beings like us to exist. — Rank Amateur

Moliere

6.5kThe thought experiment using the deck of cards, is firstly about the order of the deck of cards. When one observes something that seems ordered, and given options as to how such order came to happen between design and randomness most would view design more likely. FTA proposes the that the universe is ordered for embodied, sentient beings like us to exist. — Rank Amateur

Right. But it does so on the basis of your next sentence:

Even vary minor differences in many different criteria ( all of these are easily looked up) would make it impossible for beings like us to exist.

But what if a difference, however minor, isn't possible at all? How do we infer that these minor differences could have been the case?

Conceptually, sure. I can conceive of them being different.

But physically?

When facing such an ordered system FTA proposed design and the most probable hypothesis as to why.

I am not sure what the difference is between your point that there may have been no other options for all these varied criteria than there is than, it was designed. Sounds like a round about way of saying the same thing.

To me it's just like stating a fact. So it is physically possible that Washington, DC is not the capital of the United States. But it is not possible in reality (earmarked to a certain time) -- it is a simple fact.

A bit more abstractly, it is metaphysically possible that the gravitational constant could differ, where all other laws and constants of the universe remain the same. But it may not be physically possible, earmarked to the universe we happen to inhabit. It could just be a simple fact that has no major significance, since it could not have been otherwise.

If it could not have been otherwise, then there's no need to posit that someone made it that way. It's just the way things are. -

Rank Amateur

1.5kIf it could not have been otherwise, then there's no need to posit that someone made it that way. It's just the way things are — Moliere

Rank Amateur

1.5kIf it could not have been otherwise, then there's no need to posit that someone made it that way. It's just the way things are — Moliere

My point is, if the gravitational constant could only be what it is, and the weak force could only be what it is, and the strong force could only be what its, and on and on for a bunch of other constraints could only be what they are. And if any of those was even marginally different. Life could not exist. That sure sounds like they were designed for that purpose to me. I see no difference is saying things are as the are because they were designed as such , or there was no other alternatives. You are just moving the question up one level - why are there no other alternatives. -

Moliere

6.5kMy point is, if the gravitational constant could only be what it is, and the weak force could only be what it is, and the strong force could only be what its, and on and on for a bunch of other constraints could only be what they are. And if any of those was even marginally different. Life could not exist. That sure sounds like they were designed for that purpose to me. — Rank Amateur

Moliere

6.5kMy point is, if the gravitational constant could only be what it is, and the weak force could only be what it is, and the strong force could only be what its, and on and on for a bunch of other constraints could only be what they are. And if any of those was even marginally different. Life could not exist. That sure sounds like they were designed for that purpose to me. — Rank Amateur

To me it just looks like a fact, because I see no reason to believe they could have been otherwise -- in a physical sense.

I see no difference is saying things are as the are because they were designed as such , or there was no other alternatives. You are just moving the question up one level - why are there no other alternatives.

Well, strictly speaking I'm only posting another possibility. Strictly speaking I don't think you can rule out a designer. In a looser sense I have my beliefs and find them reasonable enough, but I can acknowledge others -- on those same looser standards -- as being reasonable enough with different conclusions.

For this particular possibility the reason the constants don't vary is because they are constant. It's just a simple fact, in the same manner that Washington DC is the capital of the United States in 2018 doesn't vary, or that when you mix yellow with red paint you getgreenorange (EDIT: lol. Temporarily forgot the actual fact. Sorry) paint. There may be more to explain than that -- Washington DC became the capital because of such and such history, or red and yellow paint makegreenorange paint because they absord such and such frequencies in the visible light spectrum -- but that explanation doesn't change the very basic fact that the gravitational constant, that the capital of the United States, and that the color combination of paints are what they are.

I suppose I should say that I don't think every fact has an explanation, either. I don't think the entirity of everything that exists has some kind of cohesive explanation. It could, but it doesn't need to. Sometimes a fact is just a fact.

To reiterate, I'm saying this is a possibility. It's one that I find more congenial than positing extra-planar beings choosing what the physical constants are, but I merely find it congenial and know that even an extra-planar being is possible, and can recognize why others might find it so even if I do not.

It could also be possible -- to give the other two examples I said -- that there is a multiverse engine creating universes, and that there is some other physical theory we do not yet know (just as we did not yet know how color worked at one point, though we still knew what color combinations would bring about which colors). -

Rank Amateur

1.5kI'm sure you'll understand why nobody would take such a proposition seriously. I'm guessing that's not exactly what you meant. Perhaps you can restate it if that's the case, so we can understand what it did mean. — andrewk

Rank Amateur

1.5kI'm sure you'll understand why nobody would take such a proposition seriously. I'm guessing that's not exactly what you meant. Perhaps you can restate it if that's the case, so we can understand what it did mean. — andrewk

Is this better -

http://commonsenseatheism.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/Collins-How-to-Rigorously-Define-Fine-Tuning.pdf -

SophistiCat

2.4kThis is exactly the point I have been trying to make. — Rank Amateur

SophistiCat

2.4kThis is exactly the point I have been trying to make. — Rank Amateur

No, not even close. The only point that you've managed to make in this discussion, and which you keep repeating over and over, as if it wasn't stupidly obvious, is that you know that you are right, and those who disagree do so only because they are prejudiced. We get it. You can stop repeating it and leave, since it is obvious that you have nothing else to say. Take Wayfarer with you, too. -

andrewk

2.1k

andrewk

2.1k

Making presumptive, and completely wrong, assumptions like that reveals the emptiness of your argument.Which is the point. You don’t have an issue with FTA because of the issue of probability, you have an issue with FTA, because you have an issue with any answer that allows for a supernatural designer. — Rank Amateur

I am completely open to theism, and have no objection to designer-based spiritualities. My only objection is to when people who, because they lack faith in the designer-based spirituality to which they try to adhere, make up silly arguments to try to prove to themselves that it's the right one.

I respect faith. I don't respect faux logic. -

Rank Amateur

1.5k

Rank Amateur

1.5k

My point is very easy to argue against. Show me another complex system where you believe chance was more probable than design, and I will readily admit I was in error.

Secondly, I do not understand the angst. Believing that a supernatural designer does not exist is completely reasonable. The atheist position that FTA is false because the probability of a supernatural designer is 0, or the strong agnostic position that it is very near zero therefore it is something else is a completely reasonable position. -

andrewk

2.1k

andrewk

2.1k

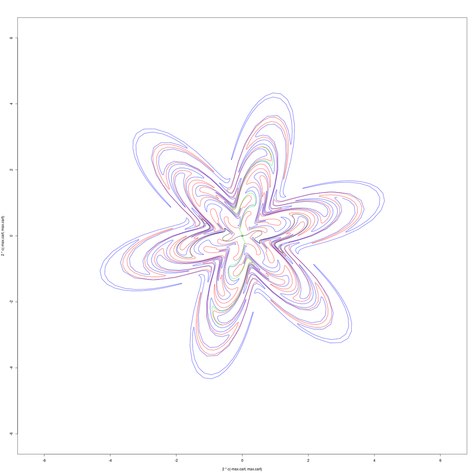

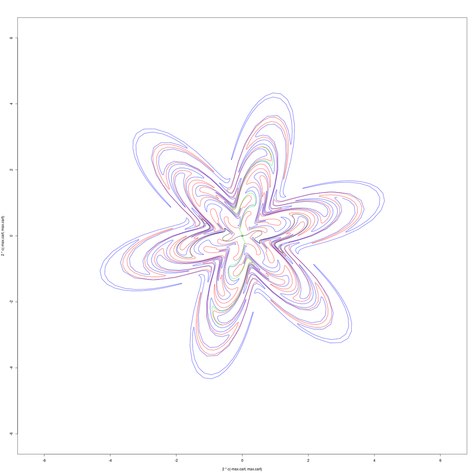

I don't know what you mean by 'chance was more probable than design', but there are plenty of systems with simple or disorganised inputs that have complex, organised-seeming outputs. Three examples that pop to mind are Conway's game of Life, Mandelbrot sets and interference patterns. I have recently been playing around with continuous endomorphisms of the number plane and found a very simple function that, to my surprise and delight, gave a lovely flower pattern as output. I have attached it below. The alternating red and blue lines are the transformed images of concentric circles.Show me another complex system where you believe chance was more probable than design — Rank Amateur

-

SophistiCat

2.4kI've been reading Robin Collins's extended treatment of the FTA in his 2009 The teleological argument: An exploration of the fine-tuning of the universe. For fairness's sake, I would like to revisit the nomalizability and the coarse-tuning objections to the probabilistic FTA, which I have talked about here, and which Collins addresses head-on.

SophistiCat

2.4kI've been reading Robin Collins's extended treatment of the FTA in his 2009 The teleological argument: An exploration of the fine-tuning of the universe. For fairness's sake, I would like to revisit the nomalizability and the coarse-tuning objections to the probabilistic FTA, which I have talked about here, and which Collins addresses head-on.

To recoup, the nomalizability objection draws attention to the fact that a uniform probability distribution, which the Principle of Indifference compels us to adopt, is undefined on an infinite domain; thus, for those fine-tuned parameters for which the range of epistemically possible values is unbounded, we cannot even have prior probabilities (this objection has been made by a number of critics of the FTA). The coarse-tuning objection points out that, even if the nomalizability problem was somehow dealt with, we would end up in a strange situation, where the width of the life-permitting region of a "fine-tuned" parameter doesn't actually matter, as long as it is finite; it could be 101010 times as wide, and this would not make any difference to the argument. (@andrewk has pointed out that the metaphor of "fine-tuning," which comes from analogue radio and instrument dials, breaks down here.)

Collins makes a number of arguments in favor of considering finite ranges in parameter space. I have already mentioned his concept of an "epistemically illuminated" (EI) region, which has an affinity with intuitive arguments made, for example, by John Leslie in his 1989 book "Universes," who at one point compares fine-tuning with a bullet hitting a lone fly on the wall: even if other, remote areas of the wall were thick with flies, he says, this would not make the pin-point precision of the hit any less surprising. I am not convinced by such analogies; I suspect that they trade on intuitions that work in familiar human surroundings, but break down in the vastness and strangeness of modern physics, especially when it comes to highly counterintuitive infinities. (For example, when we imagine bullets randomly hitting broad targets, we don't really imagine infinite targets with uniformly distributed probability; rather, we probably have in mind something like a very wide normal distribution, which is nearly flat within a finite region in front of us, but drops off to virtually zero far away from us.) In any case, if the analogy is justified, there ought to be a rigorous statement of the argument that vindicates it, and I still haven't seen any, which makes me distrustful.

Perhaps the most interesting argument that Collins makes is that we are not justified in considering unbounded ranges for physical constants, because all our scientific theories have a limited domain of applicability (for fundamental physics it is mostly the energy scale; our current theories are low-energy effective field theories). If we deviate too far from the actual values of physical constants, the very models where these constants appear break down; in those remote parameter regions we will need some different physics with different constants. This is a good point that I haven't considered in relation to the FTA, nor have I seen it addressed by FTA critics. However, my objection to this argument, as well as the less formal arguments for EI regions, is that limiting the range of epistemically possible values cannot be justified from within the Bayesian epistemic model used in the probabilistic FTA. In particular, this move doesn't sit well with already highly problematic indifference priors, which are inversely related to the size of the range. It follows that specific, finite probabilities with which we operate depend on these squishy, ill-defined choices of EI regions. Moreover, the limitations of EFTs are only contingent, and only apply to their boundary conditions and perhaps constants, but not to the mathematical form of their laws.

Although he puts the most effort into defending the idea that the size of epistemic parameter ranges is necessarily limited, Collins also considers the possibility of using non-standard probability theories, perhaps those without the requirement of the so-called finite additivity, and thus not suffering from paradoxes of uniform distributions over infinite domains*. As I said earlier, I am generally sympathetic to this idea: I am not a dogmatic Bayesian; I recognize that Bayesian epistemology is not a perfect fit to the way we actually reason, not is it a given that Bayesianism is the perfect reasoning model to which we must aspire. An epistemic model based on something other than classical Kolmogorov probability? Sure, why not? However, such a model first has to be developed and justified. And the justification had better be based on a large number and variety of uncontroversial examples, which is going to be highly problematic, because we simply lack intuitions for dealing with infinities and infinitesimals.

And that is a general problem for arguments of this type, which also include Cosmological arguments: at some point they have to appeal to our intuitions, be they epistemic or metaphysical. But the contexts in which these arguments are invoked are so far removed from our experiences that intuitions become unreliable there.

* I have also thought of another solution that he could propose to address the challenge of infinite domains, along the lines of his epistemically illuminated regions: epistemically illuminated probability distributions, which, he could argue, would be non-uniform (most likely, Gaussian). -

andrewk

2.1k

andrewk

2.1k

I would be interested to hear more about this. I'm having trouble relating it to a statement that says something about the constants.because all our scientific theories have a limited domain of applicability (for fundamental physics it is mostly the energy scale; our current theories are low-energy effective field theories). — SophistiCat

GR and QM both have limited domains of applicability. QM doesn't work in the presence of very strong gravitational fields and GR doesn't work on a very small scale, so there is an overlap region where the two contradict one another. But I can't see any way of going from that to saying something about limits for what the constants could be. Different constants may make that overlap region larger or smaller, but that seems to me to just tell us something about the approximate nature of our current theories, rather than something fundamental about the universe. That doubt seems to parallel the point you make about EFTs being contingent on a particular form of the laws. -

SophistiCat

2.4kYes, after I posted this I thought about it a bit more and realized that this wasn't actually making sense. I think I understand where Collins is coming from. Fine-tuning comes up in the context of model selection in particle physics and cosmology, but the logic there is somewhat different from that in the FTA. What happens, roughly, is that we start with a general mathematical form of the action or dynamical equations, based on general symmetry considerations or some such, in which the constants and boundary values are free parameters. This is where the problem of distributions over potentially infinite domains comes up as well. Various best-fit estimates involve marginalizing over parameters, which often results in integrals or sums over infinite domains, such as

SophistiCat

2.4kYes, after I posted this I thought about it a bit more and realized that this wasn't actually making sense. I think I understand where Collins is coming from. Fine-tuning comes up in the context of model selection in particle physics and cosmology, but the logic there is somewhat different from that in the FTA. What happens, roughly, is that we start with a general mathematical form of the action or dynamical equations, based on general symmetry considerations or some such, in which the constants and boundary values are free parameters. This is where the problem of distributions over potentially infinite domains comes up as well. Various best-fit estimates involve marginalizing over parameters, which often results in integrals or sums over infinite domains, such as

The normalizability challenge can then be answered with considerations such as that the applicability of the model is limited to a finite range of parameter values (e.g. the Planck scale), as well as considerations of "naturalness" (which present another can of worms that we need not get into.)

The bottom line is that in physics we are not agnostic about at least some general physical principles, and more often we are working with quite specific models with known properties and limitations, which can inform the choice of probability distributions. Whereas in the most general case of the FTA we are agnostic about all that. Any form of a physical law, any value of a fundamental constant represents an epistemically possible world, which we cannot discount from consideration. -

SophistiCat

2.4kI've been reading some more on the topic. An extensive review of fine-tuning for life in fundamental physics and cosmology is given by the young cosmologist Luke Barnes: The fine-tuning of the universe for intelligent life (2012) (this rather technical article served as a basis of a popular book coauthored by Barnes). He frames his article as a polemic with Victor Stenger's popular book The Fallacy of Fine-tuning: Why the Universe Is Not Designed for Us (2011), which goes beyond the ostensible thesis of its title and argues that the purported fine-tuning of the universe is not all it's cracked up to be. Barnes is a theist (as far as I know), and Stenger was, of course, one of the crop of the New Atheists, so there may be an ideological aspect to this debate. But in his academic writing, at least, Barnes stops short of making an argument for God, and having read this article (and Stenger's response), I am more persuaded by his case - as far as it goes.

SophistiCat

2.4kI've been reading some more on the topic. An extensive review of fine-tuning for life in fundamental physics and cosmology is given by the young cosmologist Luke Barnes: The fine-tuning of the universe for intelligent life (2012) (this rather technical article served as a basis of a popular book coauthored by Barnes). He frames his article as a polemic with Victor Stenger's popular book The Fallacy of Fine-tuning: Why the Universe Is Not Designed for Us (2011), which goes beyond the ostensible thesis of its title and argues that the purported fine-tuning of the universe is not all it's cracked up to be. Barnes is a theist (as far as I know), and Stenger was, of course, one of the crop of the New Atheists, so there may be an ideological aspect to this debate. But in his academic writing, at least, Barnes stops short of making an argument for God, and having read this article (and Stenger's response), I am more persuaded by his case - as far as it goes.

One thing caught my attention though. While discussing the fine-tuning of stars - their stability and the nucleosynthesis that produces chemical elements necessary for life - Barnes writes:

One of the most famous examples of fine-tuning is the Hoyle resonance in carbon. Hoyle reasoned that if such a resonance level did not exist at just the right place, then stars would be unable to produce the carbon required by life. — Barnes (2012), p. 547

He then includes this curious footnote:

Hoyle’s prediction is not an ‘anthropic prediction’. As Smolin (2007) explains, the prediction can be formulated as follows: a.) Carbon is necessary for life. b.) There are substantial amounts of carbon in our universe. c.) If stars are to produce substantial amounts of carbon, then there must be a specific resonance level in carbon. d.) Thus, the specific resonance level in carbon exists. The conclusion does not depend in any way on the first, ‘anthropic’ premise. The argument would work just as well if the element in question were the inert gas neon, for which the first premise is (probably) false. — Barnes (2012), p. 547

Barnes credits this insight to Smolin's article in the anthology Universe or Multiverse? (2007). Oddly, he himself does not make the obvious wider connection: the same argument could be just as easily applied to every other case of cosmic fine-tuning. For example, it could be similarly argued that the lower bound of the permissible values of the cosmological constant is to avoid a re-collapse of the universe shortly after the Big Bang. We know that the universe did not collapse; the additional observation that, as a consequence, intelligent life had a chance to emerge at a much later time is unnecessary to reach the conclusion with regard to the cosmological constant. And yet, in this and other publications Barnes insists on referring to every case of fine-tuning (except for carbon resonance, for some reason) as fine-tuning for life.

So why talk about life in connection with cosmic fine-tuning? Why would someone who objectively evaluates the implications of varying fundamental laws and constants of the universe - which is what Barnes ostensibly sets out to do - single out fine-tuning for life as a remarkable finding that cries out for an explanation? Well, one could argue that life is the one thing all these diverse cases of fine-tuning have in common. And the fact that the universe is fine-tuned for some feature (in the sense that this feature exhibits a sensitive dependence on fundamental parameters) to such a great extent is inherently interesting and demands an explanation.

To this it could be objected that the target seems to be picked arbitrarily. Picking a different target, one could produce a different set of (possibly fine-tuned) constraints. Indeed, in the limit, when the target is this specific universe, the constraints are going to be as tight as they could possibly be: all parameters are fine-tuned, and all bounds are reduced to zero. Is this surprising? Does this extreme fine-tuning cry out for an explanation? Certainly not! Such "fine-tuning" is a matter of necessity. Moreover, even excluding edge cases, one could always pick as small a target in the parameter space as one wishes; it then becomes a game of Texas Sharpshooting ().

Another objection is that life, being a high-level complex structure, is going to be fine-tuned (again, in the sense of being sensitive to variations of low-level parameters) no matter what. In fact, any such complex structure is bound to be fine-tuned. (Physicist R. A. W. Bradford demonstrates this mathematically in The Inevitability of Fine Tuning in a Complex Universe (2011), using sequential local entropy reduction as a proxy for emerging complexity.) So if there is something generically surprising here, it is that the universe is fine-tuned to produce any complex structures.

It seems then that, objectively speaking, whatever it is that the universe is trying to tell us, it is not that it is fine-tuned for life. What then would be a legitimate motivation for framing the problem in such a way? One such motivation can be found in the observer selection effect in the context of model selection in cosmology, where it is also known as the weak anthropic principle: out of all possible universes, we - observers - are bound to find ourselves in a universe that can support observers. Thus fine-tuning for life (or more specifically, for observers) is offered as a solution, rather than a problem. Of course, this requires a scenario with a multitude of actual universes - in other words, a multiverse. Barnes considers existing multiverse cosmological models in his paper and finds that, whatever their merits, they don't solve the fine-tuning problem; if anything, he contends, such models make the problem worse by being fine-tuned to an even greater extent.

So we come back to the question: Why do people like Barnes consider fine-tuning for life to be a problem in need of a solution? I think that theologian Richard Swinburne, who was perhaps the first to formulate a modern FTA, gave a plausible answer: we find something to be surprising and in need of an explanation when we already have a candidate explanation in mind - an explanation that makes the thing less surprising and more likely. And God, according to Swinburne, presents such an explanation in the case of intelligent life. So there is our answer: the only plausible reason to present fine-tuning for life as a problem is to make an argument for the existence of God (or something like it), and anyone who does so should deliver on that promise or risk appearing disingenuous. -

Ben Hancock

14In Robin Collins’ The Fine Tuning Argument: A Scientific Argument for the Existence of God, he mentions that one of the objections that challenges the core version of fine-tuning argument is the “Who Designed God” objection. The version from George Smith is:

Ben Hancock

14In Robin Collins’ The Fine Tuning Argument: A Scientific Argument for the Existence of God, he mentions that one of the objections that challenges the core version of fine-tuning argument is the “Who Designed God” objection. The version from George Smith is:

If the universe is wonderfully designed, surely God is even more wonderfully designed. He must, therefore, have had a designer even more wonderful than He is. If God did not require a designer, then there is no reason why such a relatively less wonderful thing as the universe needed one. (1980, p. 56.)

To put it in an argument form:

1. If the universe is designed by God, then God is more wonderfully designed than the universe.

2. If God is wonderfully designed, then he must have had a designer even more wonderful than He is.

3. If God does not have a designer even more wonderful than He is, then God is not more wonderfully designed than the universe.

4. God did not require a designer.

5. Then God is not more wonderfully designed than the universe. (3,4 MP)

6. It is not the case that the universe is wonderfully designed by God. (1,5 MT)

My response is only applicable to the version of “who designed the designer” objection above. I would like to object premise 1 by arguing that even God is the designer of the universe, he does not necessarily need a designer. To lay out my argument:

1. If God who designed the universe needs a designer, then either the designing of intelligent beings is an infinite set of successive events, or there is an Ultimate Designer who is not designed.

2. The designing of intelligent beings is not an infinite set of successive events.

3. It is not the case that there is an Ultimate Designer.

4. Therefore, it is not the case that God who designed the universe needs a designer.

If the designing of intelligent beings is an infinite set of successive events, then the following must be true:

God, who designed the universe has a designer;

God’s designer, who designed God, has a designer;

God’s designer’s designer, who designed God’s designer, has a designer;

…

Consider each level of designing as an event, it is impossible to traverse to the infinite many events before God’s creation and still have God be designed by His designer, and then designed the universe for us to live in. If we were to put the series of event on a time line, and use the designing of the universe as point 0 on the line, the designing of God as -1, and the designing of God’s designer as -2. If it is impossible to trace back to -∞ from 0, how is possible for a series of successive events started from -∞ to progress to 0. Therefore it is impossible for the designing of intelligent beings to be an infinite set of successive events.

If instead of an infinite set of successive events, there is an Ultimate Designer to trace back to, who is not designed and whose existence is necessary rather than contingent. Since the Ultimate Designer has designed the designer who is just relatively less wonderful than him, eventually this will progress to the designing of God, who is the designer of the universe. However, it seems like each designer that is between the Ultimate Designer and God only exist to design what is relatively less wonderful than himself. If the Ultimate Designer is able to design a designer who is relatively more wonderful than God, he is certainly able to design God, who is the designer of the Universe; then all the levels of designers in between the Ultimate Designer and God do not need to exist. In fact, the Ultimate Designer, who is not designed and whose existence is necessary rather than contingent, can just design the universe himself. Then we can simply refer to this Ultimate Designer as God and avoid the issue of who designed the designer. Therefore, even if the universe is designed by God, it doesn’t necessarily follow that God needs to be more wonderfully designed.

Thoughts? — CYU-5

If I understand correctly, you seem to be challenging premise 3 of Collins argument by changing the order in which we view the Big Bang. Instead of wondering how the Big Bang shaped a world so specific that humans emerged, you say that the pre-conditions to the Big Bang are irrelevant to the existence of God in that the Big Bang simply set the world in order and humans are a product of that, not a design element. In formal writing:

1. There are no required conditions for the Big Bang

2. If there are no required conditions for the Big Bang, then the outcome of the Big Bang is essentially random

3. If the outcome is random, it cannot be designed

4. Our existence naturally fits into the laws of the universe established by the outcome of the Big Bang

5. The existence of specific laws of the Universe is irrelevant to the design argument (theism)

My objection to that argument (hopefully I have represented you honestly) lies on premise 1. The idea that there are no required conditions for the big bang falls into the logical fallacy of producing something from nothing. In physics (and I am no physicist) there is the law of conservation of energy which states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed. Thomas Aquinas describes this concept in his “Argument from Motion” (https://philosophy.lander.edu/intro/motion.shtml). While a little elementary in his knowledge of physics, the thought-concept is the same. Something cannot come out of nothing, as something cannot be moved without a mover. In this way, it seems implausible to reject the idea of some sort of Creator to establish conditions for the Big Bang for it to happen (especially considering the results!). If there is a Creator, it follows that the argument of fine-tuning is relevant once more. -

Brillig

111. There are no required conditions for the Big Bang

Brillig

111. There are no required conditions for the Big Bang

2. If there are no required conditions for the Big Bang, then the outcome of the Big Bang is essentially random

3. If the outcome is random, it cannot be designed

4. Our existence naturally fits into the laws of the universe established by the outcome of the Big Bang

5. The existence of specific laws of the Universe is irrelevant to the design argument (theism) — Ben Hancock

I'm not necessarily implying that the Big Bang was random, or that randomness would necessitate lack of design. Specifically, I'm saying that new information and calculations do not support the argument for a creative designer. That was the main point I tried to illustrate in my example.

If we want to broaden the discussion to the entire argument from design, then I can provide my thoughts there as well. Firstly, "producing something from nothing" is not a type of logical fallacy. I can see why some people would take issue with the idea, but it's not a logical fallacy in the way that equivocation or appeal to authority are.

Secondly, the idea of the universe requiring an Unmoved Mover does not convince me. If the universe cannot arise from nothing, we can ask the same question about God. Who would have designed God? If God does not need a designer, then why does the universe? Collins attempts to address this in his essay, but he does not answer the question. Instead, he contends that the universe as we know it is more likely to occur under the guidance of a god-designer than out of nothing. But if that god-designer came from nothing, then I don't think we've made any real progress. We still face the same question - how can something come from nothing? God does not answer that.

And to briefly consider your example, it is true that energy cannot be created or destroyed. However, it can be transformed. Einstein's famous E = mc(^2) is an equation for converting energy into mass. I'm purely speculating here, but perhaps there was something before our universe that energy and mass came out of. Or perhaps there was nothing. I do not think the argument from design solves this problem. -

Brillig

11The trick is in the title. It should read, "A Sophistic Argument for the Existence of God," — tim wood

Brillig

11The trick is in the title. It should read, "A Sophistic Argument for the Existence of God," — tim wood

I'm not quite sure I understand what you're saying here. Do you mean that you agree with my assessment that the science does not support his argument? But that you disagree with my belief that the argument overall doesn't succeed?

It's from the same family of reasoning that proves a ham sandwich is better than God. (A ham sandwich is better than nothing,,,,) — tim wood

I realize that this was meant to be a silly example, but a ham sandwich is not better than nothing as an explanation for the universe. A ham sandwich that preceded the Big Bang would raise more questions than we already deal with. If you read my response to Ben Hancock, you'll see that I believe the idea of God does not provide us with a solution to our problem, and therefore is not better than nothing. -

Ben Hancock

14new information and calculations do not support the argument for a creative designer — Brillig

Ben Hancock

14new information and calculations do not support the argument for a creative designer — Brillig

Thank you for clarifying. The illustration you used in the first example seems to suggest that the reason the new information and calculations do not support the argument for a creative designer is because the Big Bang came first, and so human's development afterward is in relation to the 'rules' that were established at the Big Bang. However, if we look at the Big Bang first, we are still left with no answer to the question why we are here. Us being here certainly does entail that the necessary requirements for us being here were met, but offers no answer to why. Richard Dawkins responded to this objection called the anthropic principle here: (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hXpX-jLofpM). Dawkins uses and example from John Leslie quoted here: "If fifty sharp shooters all miss me, the response "if they had not missed me I wouldn't be here to consider the fact" is not adequate. Instead, I would naturally conclude that there was some reason why they all missed, such as that they never really intended to kill me. Why would I conclude this? Because my continued existence would be very improbable under the hypothesis thatthey missed me by chance, but not improbable under the hypothesis that there was some reason why they missed me. This question of why would persist no matter what the preconditions of the universe in discussion was. Observing those preconditions, and finding them to be incredibly specific, it is quite rational to then apply those statistics to a Design argument, because it is more likely that those entailing requirements would be so specific if there was an end in mind than by a random generator.

To respond to the idea that a God simply elevates the problem of intelligent design up a level, I propose that this is only a problem if we understand God as something created. If God is the greatest of all possible beings, He must be self-created and self-sustaining. The Universe is evidently not the greatest of all possible beings, as we can, in our own minds, imagine a Universe that is perfect. God, however, is not dependent on any other if He is the greatest of all possible beings, and so is created and sustained within himself. -

Grey Vs Gray

29The pont of the "who designed the designer argument" is not to ask who designed the designer but to simplify Occam's Razor. It is simpler to say the universe IS than to state the universe was created, because that is what we know. To say "God is and thus the universe is" is more complex than "the universe is." You get the drift. -

Devans99

2.7kI think if we drop time/causality and assume a timeless god with permanent existence outside time, the need for god's designer lessens: God just exists. Never created. Just is. Also, the universe is not perfect, so god cannot be perfect, so God may not have been designed.

Devans99

2.7kI think if we drop time/causality and assume a timeless god with permanent existence outside time, the need for god's designer lessens: God just exists. Never created. Just is. Also, the universe is not perfect, so god cannot be perfect, so God may not have been designed.

That does leave the question of 'why does a timeless god exist?'. Similar to the question to 'why does anything exist?'. We have the Anthropic principle to provide a pseudo-answer to 'why does anything exist?': 'we are here so it must'. Could be argued that triggering the Big Bang required an intelligence, hence a god, so the Anthropic principle would apply also: 'we are here so there must be a god'.

If there is a god and I ever meet him, I will ask why he exists. If he does not know, I will throw my hands up in disgust at the meaningless nature of existence. -

Harry Hindu

5.9k1. If God who designed the universe needs a designer, then either the designing of intelligent beings is an infinite set of successive events, or there is an Ultimate Designer who is not designed.

Harry Hindu

5.9k1. If God who designed the universe needs a designer, then either the designing of intelligent beings is an infinite set of successive events, or there is an Ultimate Designer who is not designed.

2. The designing of intelligent beings is not an infinite set of successive events.

3. It is not the case that there is an Ultimate Designer.

4. Therefore, it is not the case that God who designed the universe needs a designer. — CYU-5

The whole point to why theists claim that a Designer is necessary is because of the beautiful and complex "design" of the universe. So it would be a contradiction to then say that God is beautiful and complex but it doesn't need a designer.

What it comes down to is that the universe wasn't designed at all. That is why it doesn't need a designer. -

Dfpolis

1.3kThe pont of the "who designed the designer argument" is not to ask who designed the designer but to simplify Occam's Razor. It is simpler to say the universe IS than to state the universe was created, — Grey Vs Gray

Dfpolis

1.3kThe pont of the "who designed the designer argument" is not to ask who designed the designer but to simplify Occam's Razor. It is simpler to say the universe IS than to state the universe was created, — Grey Vs Gray

This is to misunderstand Ockham. His principle is that we are not to multiply causes without necessity. It is not, as you suggest, that we have no need for causes. -

Dfpolis

1.3kSo it would be a contradiction to then say that God is beautiful and complex but it doesn't need a designer. — Harry Hindu

Dfpolis

1.3kSo it would be a contradiction to then say that God is beautiful and complex but it doesn't need a designer. — Harry Hindu

The standard theist claim is that God is ultimately simple -- not that He is complex -

Brillig

11Again, the specific point I would like to make is that Collins' "rigorous support" for the argument from design does nothing to advance the core debate. When we ask why the Big Bang occurred, we are veering away from that point. To me, it seems that in saying

Brillig

11Again, the specific point I would like to make is that Collins' "rigorous support" for the argument from design does nothing to advance the core debate. When we ask why the Big Bang occurred, we are veering away from that point. To me, it seems that in saying

that you agree with my original point. Am I understanding you incorrectly?This question of why would persist no matter what the preconditions of the universe — Ben Hancock

Separately, I can understand why it seemed as though I was invoking a version of the anthropic principle in my original post. I was not attempting to do so, and perhaps my example could have been more clear. I fully agree with the story about the sharp shooters.

However, to broaden our discussion again, I disagree with many points in your final paragraph. It also seems as though you are drawing on the ontological argument, which is a separate line of reasoning from the design argument. I'll attempt to address both briefly.

I could also contend that this is only a problem if we understand the universe as something created. The Big Bang implies a beginning, not a creation. And to put on my (very inadequate) speculative astrophysicist hat, perhaps the Big Bang is not even a beginning, but simply the start of a form that we recognize. We do not know what came before.this is only a problem if we understand God as something created — Ben Hancock

Is it true that we can imagine a perfect universe? What are the specific requirements? I find it hard to imagine a concrete list of attributes that compose a perfect universe. Perhaps I could suggest a few improvements, but by no means does that imply a finite list of steps to take to reach perfection. So, in fact, I'd say we can't really imagine a perfect universe.The Universe is evidently not the greatest of all possible beings, as we can, in our own minds, imagine a Universe that is perfect. God, however, is not dependent on any other if He is the greatest of all possible beings — Ben Hancock

Similarly, I find it difficult to imagine what a greatest of all possible beings would look like. I can easily attach adjectives to this being -- omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent -- but these attributes raise intricate questions that the Big Bang does not. When we first engage the origins of the universe, we ask one complex question: is there a cause for the Big Bang? When we arrive at the solution of a self-creating God, we must ask many complex questions. Personally, I do not find it satisfying to trade one mystery for several.

To clarify, I am not implying that an atheistic view of the universe offers more answers than a theistic one. I am saying that when we wonder about the Cause of Everything, our current notions of God should not satisfy us. -

Grey Vs Gray

29This is to misunderstand Ockham. His principle is that we are not to multiply causes without necessity. It is not, as you suggest, that we have no need for causes. — Dfpolis

Occam's point is to pick the simplest solution when given a choice. We see the universe but we don't see god. The simplest deduction is the universe is and god is not. That does not mean there is no god, it's simply one of the methods I use to justify my opinion.

The purpose of who designed the designer is for atheists to point out the added complexity of a designed universe. If god can just be, so can the universe. -

Devans99

2.7kWe see the universe but we don't see god. The simplest deduction is the universe is and god is not. That does not mean there is no god, it's simply one of the methods I use to justify my opinion. — Grey Vs Gray

Devans99

2.7kWe see the universe but we don't see god. The simplest deduction is the universe is and god is not. That does not mean there is no god, it's simply one of the methods I use to justify my opinion. — Grey Vs Gray

If we expect to see God, we will be disappointed; the universe is too large and too young for God to have had time to see us:

- 1 x 10^24 estimated stars in observable universe

- 5.1 x 10^12 days since start of universe

- God must visit 195,694,716,242 star systems a day for God to have visited all star systems in the observable universe by today.

Talk about a hectic schedule. Lack of communication from God can't be taken as strong evidence for his non-existence. -

Grey Vs Gray

29Devans99

You'll get no argument from me that there is a possibility of a god. My only certainty is that god's of human invention are just that, inventions. I personally think a non-created universe is more likely but not a certainty. -

Devans99

2.7k

Devans99

2.7k

Yes, it strikes me as strange no-one tries to formulate a more believable religion than the ones we have currently. A Religion with a creation story rooted in arguments from physics and metaphysics. A religion that would appeal to the rational thinker.My only certainty is that god's of human invention are just that, inventions — Grey Vs Gray

I personally think a non-created universe is more likely but not a certainty. — Grey Vs Gray

I mess with probability a lot trying to work out the likelihood of God. I'm coming out more positive than you but who knows... -

Dfpolis

1.3kOccam's point is to pick the simplest solution when given a choice — Grey Vs Gray

Dfpolis

1.3kOccam's point is to pick the simplest solution when given a choice — Grey Vs Gray

A non-explanation is not a solution. It is a cop out.

We see the universe but we don't see god. The simplest deduction is the universe is and god is not. — Grey Vs Gray

You seem not to understand how deduction works. It is far different from jumping to conclusions. We can see rainbows, but we cannot see the law of conservation of mass-energy. Does that mean that there are colored structures in the sky, but no laws of nature? Not to a rational mind.

If god can just be, so can the universe. — Grey Vs Gray

No, not if you want to think rationally. For science to work, everything must have an adequate explanation, even if we do not know it. If you admit exceptions, then any new phenomena could "just be." It is only because we know this is not so, that science seeks adequate explanations. Thus, everything, including God must have an adequate explanation. The distinguishing things about God is that, as the end of the line of explanation, God cannot be explained by something else (or he would not be the end of the line). So, God must be self-explaining.

Not just anything can be self explaining. If A explains B, the nature of A is sufficient to account for B. That means that if God is self-explaining, what God is must entail that God is.

Let's reflect on that. As intimated by Plato in the Sophist, anything that can act in any way in any way exists. Conversely, some "thing" that can do absolutely nothing, cannot evoke the concept of existence in us and so does not exist. So, existence is convertible with the capacity to act. Existence is not the ability to act in this way or that way, but the unspecified ability to act.

Extending this line of thought, if we knew everything that an object could do, we would have an exhaustive knowledge of what it is. If something can do everything a duck can do, and noting a duck cant do, it is a duck. Thus, essences, what things are, are specifications of an object's possible acts.

Putting these pieces together, if a being is to be self-explaining, its essence (the specification of its possible acts) must entail its existence (the unspecified ability to act). That means that the range of its possible acts cannot be limited, for then it would not entail the unspecified ability to act. So, a being can only be self-explaining if it can do any possible act. The universe cannot do any logically possible act.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum