-

ADG

1The debate between Norton and Brown regarding whether thought experiments transcend empiricism is interesting with Norton suggesting that thought experiments do not transcend empiricism.

ADG

1The debate between Norton and Brown regarding whether thought experiments transcend empiricism is interesting with Norton suggesting that thought experiments do not transcend empiricism.

If one had to choose a thought experiment to defend Norton's view, would Galileo's thought experiment that two falling bodies fall with the same acceleration be a suitable thought experiment since it can be empirically tested and it also can be written in a premise and conclusion argument form. I am not sure whether this would be a deductive argument though.

Also, wouldn't the assumption that connecting the heavier (H) and lighter ( L ) body makes one body of weight (H + L) mean that one of the premises of the argument would be false.

Thank you for your help! -

SophistiCat

2.4kThis post would benefit from some background reading suggestions for those who do not know what you are talking about.

SophistiCat

2.4kThis post would benefit from some background reading suggestions for those who do not know what you are talking about.

John Norton, Why thought experiments do not transcend empiricism (2002)

James Brown, Why thought experiments transcend empiricism (2004)

John Norton's other publications on the topic.

SEP Thought Experiments -

Terrapin Station

13.8kIt was never clear to me just what the claim was supposed to be here anyway re "transcending empiricism." Did Brown ever precisely define just what "transcending empiricism" was supposed to amount to?

Terrapin Station

13.8kIt was never clear to me just what the claim was supposed to be here anyway re "transcending empiricism." Did Brown ever precisely define just what "transcending empiricism" was supposed to amount to? -

Josh Alfred

225I think all thought experiments, if they are to be totally used for verification of a theory, should be able to be put into a real experiment/demonstrated.

Josh Alfred

225I think all thought experiments, if they are to be totally used for verification of a theory, should be able to be put into a real experiment/demonstrated.

Einstein is famous for his thought experiments. One such experiment is "riding a wave of light", what would that be like, how fast would you be moving, how does it related back to relativity, etc.. Does the thought experiment help to predict any real instances of light (having velocity)? And does the experiment itself transcend the empirical? -

sime

1.2kDrawing upon Wittgenstein, one might say that the meaning of a thought experiment is how it is used. Hence thoughts 'in themselves' do not express impossibility.

sime

1.2kDrawing upon Wittgenstein, one might say that the meaning of a thought experiment is how it is used. Hence thoughts 'in themselves' do not express impossibility.

Impossibility refers to the expression of a thought that isn't usable within in the context of a given language-game. For example, if somebody claims to imagine a heavy object travelling at or beyond the speed of light, they aren't wrong in terms of *what* they imagine, rather the contents of their imagination isn't a model of relativity; but their imagination will be a model of some other theory. -

Arkady

768

Arkady

768

I've never understood how Aristotelian physics (specifically, the claim that heavier bodies fall faster than light ones) is supposedly disproven a priori from the paradox about falling bodies which is ascribed to it.

It is perfectly reasonable to assume that, when a lighter mass is yoked to a heavier mass, they thereby become one object, which is heavier than either alone (and therefore would fall faster than the heavier object alone). Therefore, the theory does not imply that the composite object would somehow both fall faster and slower than the heavier object alone.

Aristotelian physics has been thoroughly empirically falsified, of course, in part by experiments that Galileo himself performed, but this is a different matter from claiming that its tenets lead to a contradiction, and thus that it can be disproven a priori. -

Inis

243The debate between Norton and Brown regarding whether thought experiments transcend empiricism is interesting with Norton suggesting that thought experiments do not transcend empiricism. — ADG

Inis

243The debate between Norton and Brown regarding whether thought experiments transcend empiricism is interesting with Norton suggesting that thought experiments do not transcend empiricism. — ADG

Given that Empiricism, the doctrine that knowledge is derived from the senses, is objectively false, I would hope we could get beyond it, if not transcend it.

If one had to choose a thought experiment to defend Norton's view, would Galileo's thought experiment that two falling bodies fall with the same acceleration be a suitable thought experiment since it can be empirically tested and it also can be written in a premise and conclusion argument form. I am not sure whether this would be a deductive argument though. — ADG

Inconsistencies are the greatest flaw in any theory, rendering them immediately problematic. Famously, right now, we have inconsistencies between theories, rendering each problematic, despite there being zero empirical evidence that either theory has problems, and no one can even come up with a suitable thought experiment.

But thought experiments cut both ways. The famous EPR paradox was supposed to render quantum mechanics problematic, by claiming certain predictions of QM were absurd. Instead it discovered an unexpected feature of Reality that may turn out to be the most technologically significant of all time.

Also, wouldn't the assumption that connecting the heavier (H) and lighter ( L ) body makes one body of weight (H + L) mean that one of the premises of the argument would be false. — ADG

No. Connect them with a very long piece of weightless, inelastic string (as you might do in a thought experiment). -

MindForged

731Given that Empiricism, the doctrine that knowledge is derived from the senses, is objectively false, I would hope we could get beyond it, if not transcend it. — Inis

MindForged

731Given that Empiricism, the doctrine that knowledge is derived from the senses, is objectively false, I would hope we could get beyond it, if not transcend it. — Inis

This kind of statement sounds really unthinking. Making such grandiose statements as if they were trivialities is not a very good way to argue. If empiricism were objecrively false one would expect this to be represented amongst philosophers views. But the opposite is true, according to the PhilPapers survey more philosophers are empiricists than rationalists by a decent margin(8-9%), and those who are neither strictly empiricist nor rationalists out number both the rationalists and the empiricists. If this does this at all sway you to speak less assuredly I'd be rather surprised. No one would talk about views in, say, quantum mechanical interpretations this way so doing so here frankly sounds stupid.

Inconsistencies are the greatest flaw in any theory, rendering them immediately problematic. Famously, right now, we have inconsistencies between theories, rendering each problematic, despite there being zero empirical evidence that either theory has problems, and no one can even come up with a suitable thought experiment. — Inis

This doesn't seem quite true. Several inconsistencies between the theories results in false predictions when applied in each other's domains, yes? Applying general relativity at quantum scales results in infinities we can't renormalize and applying quantum mechanics as cosmological scales predicts fields with energy levels that would result in enormous black holes, and neither of these are observed. -

Inis

243This kind of statement sounds really unthinking. Making such grandiose statements as if they were trivialities is not a very good way to argue. If empiricism were objecrively false one would expect this to be represented amongst philosophers views — MindForged

Inis

243This kind of statement sounds really unthinking. Making such grandiose statements as if they were trivialities is not a very good way to argue. If empiricism were objecrively false one would expect this to be represented amongst philosophers views — MindForged

You mean philosophers like Popper, who wrote literally books refuting empiricism? - see Logic of Scientific Discovery, and Conjectures and Refutations. Kuhn and Feyerabend also refuted empiricism, and let's not forget the venerable Quine-Duhem thesis (it's not a problem since Popper solved it).

There was also Kant, of course, and all the "rationalist" philosophers you care to name.

I would also like to give an honourable mention to Hume. While he is generally regarded as an empiricist, he set up the problems that brought empiricism down.

So, the doctrine that "knowledge is derived from the senses" is well and truly a dead doctrine, and I am thoroughly surprised if anyone is wasting their time on it.

No one would talk about views in, say, quantum mechanical interpretations this way so doing so here frankly sounds stupid. — MindForged

GRW is not quantum mechanics, Bohm has been refuted so many times it's getting boring, Copenhagen is psychology. These are all standard views in foundations of QM.

And, you call me "stupid"?

This doesn't seem quite true. Several inconsistencies between the theories results in false predictions when applied in each other's domains, yes? Applying general relativity at quantum scales results in infinities we can't renormalize and applying quantum mechanics as cosmological scales predicts fields with energy levels that would result in enormous black holes, and neither of these are observed. — MindForged

I hope you appreciate the irony in your appeal to thought experiments to defend empiricism!

You are confusing the two theories, for which there is zero empirical evidence against, with theoretical problems encountered in the attempts to unify them. Empirical evidence is literally irrelevant at this point, it's all about theoretical consistency. Ask a String theorist. -

MindForged

731You mean philosophers like Popper, who wrote literally books refuting empiricism? - — Inis

MindForged

731You mean philosophers like Popper, who wrote literally books refuting empiricism? - — Inis

It's strange, it's as if you think philosophy is done by a few major names whilst ignoring progress in the field in the more than 50 years since Popper (and far longer for Kant) were anything like representative of the current state of the debate. This is absurd.

GRW is not quantum mechanics, Bohm has been refuted so many times it's getting boring, Copenhagen is psychology. These are all standard views in foundations of QM. — Inis

Bohm hasn't been refuted, Copenhagen isn't psychology (no matter what you think about wave function collapse you're misrepresenting it) and neither is, in terms of empirical support, any better than the other currently. But all of that is besides the point (which you ignored) that no one short of an outright ideologue talks like this innthe actual debate about these views.

I hope you appreciate the irony in your appeal to thought experiments to defend empiricism! — Inis

I didn't mention or use any thought experiments at all. A prediction made by a model is not a thought experiment. The models say X will be seen under Y conditions, but we don't see those in the cases where we apply Relativity and QM models outside the domain they've been successful.

You are confusing the two theories, for which there is zero empirical evidence against, with theoretical problems encountered in the attempts to unify them. Empirical evidence is literally irrelevant at this point, it's all about theoretical consistency. Ask a String theorist. — Inis

Can you keep track of your own points? You mentioned the inconsistencies between QM and Relativity and claimed there was no empirical evidence against either but that's not true. The empirical evidence against them isn't even up for debate in the domains they weren't made for (Relativity for quantum scale events and QM for macroscopic events). This point had nothing to do with QM interpretations, that was the previous point regarding your ridiculous way of speaking and dismissing other theories (or interpretations) in a way no professional would. That's on the level of ideological attachment (or rejection, in this case). -

TheMadFool

13.8kWhy does anything have to ''transcend'' anything else. Everything has its merits and demerits.

I think the thought experiments and empericism complement each other and I see a friendly handshake instead of fisticuffs if you know what I mean.

Perhaps it's about truth and which of the two gets us there with better accuracy.

Well, I just read the link and Galileo's thought experiment with his two balls:grin: won out on Aristotle's empericism.

Yet, one must point out that had Aristotle some means to a vacuum his actual physical experiment would've produced the same result as Galileo's.

I guess one tests the othe and they must be used in conjunction rather than having to prefer one over the other. -

SophistiCat

2.4kSo, the doctrine that "knowledge is derived from the senses" is well and truly a dead doctrine, and I am thoroughly surprised if anyone is wasting their time on it. — Inis

SophistiCat

2.4kSo, the doctrine that "knowledge is derived from the senses" is well and truly a dead doctrine, and I am thoroughly surprised if anyone is wasting their time on it. — Inis

Is this literally the doctrine with which Norton, Brown, et al. are concerned? Have you actually looked at any of the literature? Do you think it reasonable to believe that these and a sizable proportion of other contemporary philosophers would be "wasting their time" on something that is "objectively false" and "well and truly a dead"?

GRW is not quantum mechanics, Bohm has been refuted so many times it's getting boring, Copenhagen is psychology. These are all standard views in foundations of QM.

And, you call me "stupid"? — Inis

I have to say, you leave me little choice. -

sime

1.2kThought experiments are nothing but a form of empirical simulation. For any thought experiment can be substituted for a publicly demonstrable virtual reality simulation. But a simulation isn't a simulation of anything until it is actively compared against some other empirical process by using some measure of similarity.

sime

1.2kThought experiments are nothing but a form of empirical simulation. For any thought experiment can be substituted for a publicly demonstrable virtual reality simulation. But a simulation isn't a simulation of anything until it is actively compared against some other empirical process by using some measure of similarity.

Once this is grasped it is trivial to understand, for instance, how Zeno's paradoxes fail as thought experiments concerning motion. The lunacy becomes clear when a proponent of the argument is forced to demonstrate the paradox with an actual arrow.

Zeno's arguments are better understood to be a thought experiments for Heisenberg's uncertainty principle. You can analyse the arrow's exact position at any given time, but in order to do so you first have to stop the arrow and thereby destroy it's actual motion. But these argument's are still not a priori or "non-empirical" whatever that means, rather they are phenomenological and involve memories and imagined possibilities. -

MindForged

731Ehh, that's not a correct representation of what's wrong with Zeno's paradoxes. The fact that an actual arrow may be fired (or one may outrin a tortoise) shows that something is wrong but it doesn't tell you what is wrong. Aristotle claimed the problem was the idea that an actual infinity (the division of space infinitely) was possible was the false assumption in the argument. However, we know believe Aristotle to have been very wrong. Distance can be infinitely divided, but the time it takes to cross that each segment decreases appropriately so it sort of cancels out.

MindForged

731Ehh, that's not a correct representation of what's wrong with Zeno's paradoxes. The fact that an actual arrow may be fired (or one may outrin a tortoise) shows that something is wrong but it doesn't tell you what is wrong. Aristotle claimed the problem was the idea that an actual infinity (the division of space infinitely) was possible was the false assumption in the argument. However, we know believe Aristotle to have been very wrong. Distance can be infinitely divided, but the time it takes to cross that each segment decreases appropriately so it sort of cancels out.

This wasn't understood until we had calculus and developed a formal understanding of infinity via Cantor, Dedekind, Balzano and co., so it's definitely not a trivial discovery. -

sime

1.2k

sime

1.2k

Sadly one cannot appeal to mathematics without begging the question. Sure, a normalised infinite geometric series equals 1, which is to say that it is the upper and lower bound of any finitely extended geometric series. But the only way of assigning time intervals to each term of the associated geometric sequence, say {0.5,0.25,0.125...} is to ignore the application of zeno's argument to each and every term.

And the only way to reach the value of the bound is to literally sum an infinite number of terms, which assumes the existence of a hyper-task that mathematicians do not possess -unless , say, motion is considered to represent such a hyper-task, which is precisely what Zeno's argument calls into question. -

sime

1.2kZeno's paradox even applies to each of the infinitesimally small elements of a supposed hyper-task. Suppose we use a non-standard calculus that defines a "hyper-real" number 'epsilon' that is both positive and yet infinitely smaller than every positive real number such that it's value when multiplied by the 'number' of natural numbers equals 1.

sime

1.2kZeno's paradox even applies to each of the infinitesimally small elements of a supposed hyper-task. Suppose we use a non-standard calculus that defines a "hyper-real" number 'epsilon' that is both positive and yet infinitely smaller than every positive real number such that it's value when multiplied by the 'number' of natural numbers equals 1.

If you are prepared to swallow arguments of classical logic that permit such a thing , then as I recall, it can also be shown that the logic permits models of "hyper-hyper-real" numbers that are infinitesimally smaller than epsilon, and so on, without bottom. So one cannot appeal to the notion of infinitesimals and hyper-tasks without running into "higher-order" zeno's paradoxes. -

Inis

243Thought experiments are nothing but a form of empirical simulation. For any thought experiment can be substituted for a publicly demonstrable virtual reality simulation. But a simulation isn't a simulation of anything until it is actively compared against some other empirical process by using some measure of similarity. — sime

Inis

243Thought experiments are nothing but a form of empirical simulation. For any thought experiment can be substituted for a publicly demonstrable virtual reality simulation. But a simulation isn't a simulation of anything until it is actively compared against some other empirical process by using some measure of similarity. — sime

Your point about VR is interesting, because in the case of Galileo's paradox, you cant' do it. You can't program a logically inconsistent physical situation under any laws of physics, and you can't render the inconsistency as VR. Not many thought-experiments are this devastating, and empiricism strictly not required!

Once this is grasped it is trivial to understand, for instance, how Zeno's paradoxes fail as thought experiments concerning motion. The lunacy becomes clear when a proponent of the argument is forced to demonstrate the paradox with an actual arrow. — sime

I think Zeno is a bit of a red-herring. The arrow behaves according to the laws of physics, which disagree with Zeno's purported analysis of the motion.

Zeno's arguments are better understood to be a thought experiments for Heisenberg's uncertainty principle. You can analyse the arrow's exact position at any given time, but in order to do so you first have to stop the arrow and thereby destroy it's actual motion. But these argument's are still not a priori or "non-empirical" whatever that means, rather they are phenomenological and involve memories and imagined possibilities. — sime

I wonder from which particular sensory perceptions, Heisenberg derived his uncertainty principle? -

aletheist

1.5k

aletheist

1.5k

The paradox arises from treating space and time as composed of discrete elements of any kind, rather than recognizing space-time as a true continuum, such that motion is the fundamental reality--not positions or instants, which we arbitrarily mark for the purpose of measurement and analysis.Zeno's paradox even applies to each of the infinitesimally small elements of a supposed hyper-task. — sime -

SophistiCat

2.4kThought experiments are nothing but a form of empirical simulation. For any thought experiment can be substituted for a publicly demonstrable virtual reality simulation. — sime

SophistiCat

2.4kThought experiments are nothing but a form of empirical simulation. For any thought experiment can be substituted for a publicly demonstrable virtual reality simulation. — sime

Thought experiments can be more than that. Some thought experiments explicitly assume counterfactual conditions, unphysical idealizations, etc. The interpretation, the lessons and the value of such gedanken are often controversial. -

Inis

243Can you keep track of your own points? You mentioned the inconsistencies between QM and Relativity and claimed there was no empirical evidence against either but that's not true. The empirical evidence against them isn't even up for debate in the domains they weren't made for (Relativity for quantum scale events and QM for macroscopic events). This point had nothing to do with QM interpretations, that was the previous point regarding your ridiculous way of speaking and dismissing other theories (or interpretations) in a way no professional would. That's on the level of ideological attachment (or rejection, in this case). — MindForged

Inis

243Can you keep track of your own points? You mentioned the inconsistencies between QM and Relativity and claimed there was no empirical evidence against either but that's not true. The empirical evidence against them isn't even up for debate in the domains they weren't made for (Relativity for quantum scale events and QM for macroscopic events). This point had nothing to do with QM interpretations, that was the previous point regarding your ridiculous way of speaking and dismissing other theories (or interpretations) in a way no professional would. That's on the level of ideological attachment (or rejection, in this case). — MindForged

There is no empirical evidence that QM or GR are problematic at any scale.

You are still confusing the respective theories with theories of how they might be unified. -

MindForged

731Sadly one cannot appeal to mathematics without begging the question — sime

MindForged

731Sadly one cannot appeal to mathematics without begging the question — sime

Unless you can actually provide an alternative mathematical formalism that is as credible and useful as standard classical mathematics this is a nonsense claim. Alternatives exist but with rare exception they are of philosophical interest as opposed to mathematical ones. It's not begging the question to use the most accepted and applicable theory in the relevant details. It's quite literally the opposite.

But the only way of assigning time intervals to each term of the associated geometric sequence, say {0.5,0.25,0.125...} is to ignore the application of zeno's argument to each and every term. — sime

How does it ignore it? Doing calculations with infinities (even the continuum) is old hat now, real analysis and calculus exist. You can argue whether or not this model is the best model for real space, but currently all dominant and used models of spacetime treat it as a continuum and is understood by classical mathematics just as the rest of science has it's underlying math understood via ZFC.

And the only way to reach the value of the bound is to literally sum an infinite number of terms, which assumes the existence of a hyper-task that mathematicians do not possess -unless , say, motion is considered to represent such a hyper-task, which is precisely what Zeno's argument calls into question. — sime

Again, if you just object (sans argument) to the most useful mathematics in history that's on you. But summing an infinite number of terms can be done in calculus. It isn't even clear that the base assumptions that go into Zeno's paradoxes are true. You haven't argued for them, and most of the time their justification is just treated as somehow obvious despite the conclusion being demonstrably false.

I mean let's just make it fun. If a hypertask were impossible, there would be no motion or change. There is motion and change. Therefore hypertasks are not impossible. And given our best models of spacetime characterize space consistently with this conclusion, it's not like you're presenting a serious empirical issue with infinitely divisible space. You either have to point out a logical impossibility with infinity (but no contradictions exist), explain why infinity is perfectly acceptable in math but not in models of the physical world or you need to show what observations ought to make us change our models of spacetime as a continuum. Otherwise I don't see how your position is supposed to hold any merit over the standard one. -

sime

1.2k

sime

1.2k

You are free to call a hypertask the motion of an arrow by saying "this moving arrow is a hypertask", which says nothing other than "this is a moving arrow", but you cannot derive the conclusion that motion is a hypertask through summation of individual terms of a series. For there is no notion of "infinite summation" in standard calculus except as a figure speech referring to a bound of the sum of finitely extended finite series that is defined via the principle of induction. You are possibly mistaking the principle of mathematical induction for a proof that a hypertask summation can terminate at a finite value, when mathematical induction is merely a definition for what "infinite series" means in the sense of a bound with respect to finite series. -

SophistiCat

2.4kSo, turning back to the OP for a change :)

SophistiCat

2.4kSo, turning back to the OP for a change :)

If one had to choose a thought experiment to defend Norton's view, would Galileo's thought experiment that two falling bodies fall with the same acceleration be a suitable thought experiment since it can be empirically tested and it also can be written in a premise and conclusion argument form. I am not sure whether this would be a deductive argument though.

Also, wouldn't the assumption that connecting the heavier (H) and lighter ( L ) body makes one body of weight (H + L) mean that one of the premises of the argument would be false. — ADG

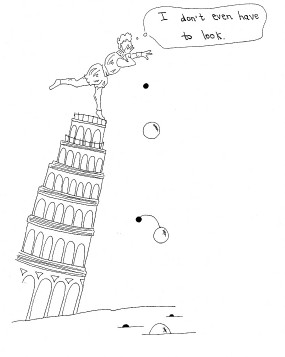

This refers to Galileo's famous argument against the then prevailing Aristotle's theory of falling bodies, according to which "bodies of different weight... move in one and the same medium with different speeds which stand to one another in the same ratio as the weights." While the apocryphal story says that Galileo conducted an actual experiment by dropping weights from the tower of Pisa, there is no evidence that he actually did this. All we have is a fictional dialogue between three characters. While one of the characters in the dialogue claims to have conducted an experiment of some sort, Galileo's stand-in declares that "without experiment, I am sure that the effect will happen as I tell you, because it must happen that way."

Galileo's argument is brilliant in its simplicity: Take two bodies of different weight connected by a string and drop them together. According to Aristotle, the lighter body will tend to fall slower than the heavier body, retarding its motion. Therefore, the two bodies together will fall slower than the heavier of the two would have fallen alone. But the combined weight of the tied bodies is greater than the weight of either of them, so again, according to Aristotle, the two should be falling faster. A contradiction.

However, as is often the case with thought experiments, this proof can be challenged. Galileo's reductio works by treating the two bound bodies as separate bodies in one part of the proof and as one combined body in another. But is it a legitimate move? Aristotle doesn't say anything about how parts of a bound system should move - he only considers separate bodies. Moreover, while he says that "each falling body acquires a definite speed fixed by nature," it would be implausible to suppose that that definite speed is acquired instantaneously - presumably, some acceleration is taken for granted. So a charitable reading would say that when two separate bodies are dropped side by side, at some later time their speeds will "stand to one another in the same ratio as the weights."

Consider Galileo's setup: two bodies of unequal weight tied by a light string and dropped from a height. If at first the string is loose, the two bodies behave as separate bodies (notice how we are already importing our physical intuitions into the thought experiment!) If that's the case, then according to Aristotle, the heavier body will be falling faster than the lighter one, but that cannot go on forever: at some point the string will go taught. At that point we can treat the two bodies as one (again, a physical intuition). This combined body, if it stays whole (which it won't, but let's disregard that) will, according to Aristotle, eventually acquire a higher speed than either of the two separate bodies had before they combined. But as long as it behaves as one body, we cannot compare its motion to the motion of its parts, since the parts are not separate and independent, nor have they been falling side by side with the combined body: there was a discontinuous transition from two falling bodies to one.

So my conclusion is that Galileo's thought experiment, while suggestive (it seems implausible that the two bodies will lurch forward as soon as they come in contact with each other), doesn't constitute a reductio against Aristotle. -

Inis

243At that point we can treat the two bodies as one (again, a physical intuition). This combined body, if it stays whole (which it won't, but let's disregard that) will, according to Aristotle, eventually acquire a higher speed than either of the two separate bodies had before they combined. But as long as it behaves as one body, we cannot compare its motion to the motion of its parts, since the parts are not separate and independent, nor have they been falling side by side with the combined body: there was a discontinuous transition from two falling bodies to one. — SophistiCat

Inis

243At that point we can treat the two bodies as one (again, a physical intuition). This combined body, if it stays whole (which it won't, but let's disregard that) will, according to Aristotle, eventually acquire a higher speed than either of the two separate bodies had before they combined. But as long as it behaves as one body, we cannot compare its motion to the motion of its parts, since the parts are not separate and independent, nor have they been falling side by side with the combined body: there was a discontinuous transition from two falling bodies to one. — SophistiCat

It seems you have missed the point entirely. According to Aristotle:

1. The tension in the string is caused by the smaller body slowing down the larger body.

2. The tension in the string causes the smaller body to speed up the larger body.

If you don't see the glaringly obvious logical contradiction, then you just need to accept that everyone else does.

And as for your snark:

(notice how we are already importing our physical intuitions into the thought experiment!) — SophistiCat

Yes, no observation, no experiment, and no thought experiment can ever be free of background knowledge including a plethora of ideas and theories. Hence empiricism is false. -

SophistiCat

2.4kIt seems you have missed the point entirely. According to Aristotle: — Inis

SophistiCat

2.4kIt seems you have missed the point entirely. According to Aristotle: — Inis

Right back at you. As I said right before the paragraph that you quoted, Aristotle (as per Galileo) does not treat of bound systems - his law concerns separate bodies. Galileo wants to stretch Aristotle's premises in a way that is, admittedly, physically intuitive, but strictly speaking, he cannot trap Aristotle in a contradiction by changing his premises. -

Inis

243Right back at you. As I said right before the paragraph that you quoted, Aristotle (as per Galileo) does not treat of bound systems - his law concerns separate bodies. Galileo wants to stretch Aristotle's premises in a way that is, admittedly, physically intuitive, but strictly speaking, he cannot trap Aristotle in a contradiction by changing his premises. — SophistiCat

Inis

243Right back at you. As I said right before the paragraph that you quoted, Aristotle (as per Galileo) does not treat of bound systems - his law concerns separate bodies. Galileo wants to stretch Aristotle's premises in a way that is, admittedly, physically intuitive, but strictly speaking, he cannot trap Aristotle in a contradiction by changing his premises. — SophistiCat

Sure, tension, acting upwards, both slows down and speeds up the larger mass. It's a logical contradiction, really it is. -

Arkady

768

Arkady

768

I largely agree with your treatment of this question, Sophisticat. However, the above assumption (i.e. that the falling bodies behave as if they're separate bodies until the string is taut) seems debatable to me: as the weights were connected by the tether prior to their being dropped, they've always been "one body," and thus it could be argued that the composite body comprising the two weights plus tether would always fall faster than either body alone, given that they've always been one object for the purposes of this experiment. (I am familiar with this thought experiment, but not well-versed in its detailed treatment in the literature. I wonder how much of a point of contention this particular issue is.)Consider Galileo's setup: two bodies of unequal weight tied by a light string and dropped from a height. If at first the string is loose, the two bodies behave as separate bodies (notice how we are already importing our physical intuitions into the thought experiment!) — SophistiCat

An interesting side note to all of this is that, if Aristotelian physics (or, at least the part of the theory which posits that heavier objects fall faster than light ones) really does imply a contradiction, one must reach the modal conclusion that there are no possible worlds in which heavier objects accelerate faster than light ones under the force of gravity alone! Intuitively speaking (for my intuition, anyway), it seems odd to put such a seemingly contingent physical fact on par with blatant contradictions such as square circles, or objects which are both red all over and green all over, etc. -

Inis

243I largely agree with your treatment of this question, Sophisticat. However, the above assumption (i.e. that the falling bodies behave as if they're separate bodies until the string is taut) seems debatable to me: — Arkady

Inis

243I largely agree with your treatment of this question, Sophisticat. However, the above assumption (i.e. that the falling bodies behave as if they're separate bodies until the string is taut) seems debatable to me: — Arkady

As I made explicit earlier, the tension only exists when the bodies are separate. When they begin falling at the same rate, the tension is zero, to they are not composite.

It's a blatantly obvious contradiction.

An interesting side note to all of this is that, if Aristotelian physics (or, at least the part of the theory which posits that heavier objects fall faster than light ones) really does imply a contradiction, one must reach the modal conclusion that there are no possible worlds in which heavier objects accelerate faster than light ones under the force of gravity alone! — Arkady

As was also mentioned earlier, it is not even possible to render a virtual reality simulation of such an environment, because it is inconsistent.

I also mentioned empiricism is false. -

Arkady

768

Arkady

768

You are only insistently repeating things you've already said, while passing them off as indubitable conclusions. I get that you are very convinced of your beliefs, but perhaps the rest of us don't necessarily share them. If you have nothing new to add, perhaps seek a different thread. -

Inis

243You are only insistently repeating things you've already said, while passing them off as indubitable conclusions. I get that you are very convinced of your beliefs, but perhaps the rest of us don't necessarily share them. If you have nothing new to add, perhaps seek a different thread. — Arkady

Inis

243You are only insistently repeating things you've already said, while passing them off as indubitable conclusions. I get that you are very convinced of your beliefs, but perhaps the rest of us don't necessarily share them. If you have nothing new to add, perhaps seek a different thread. — Arkady

Nevertheless, you cannot weasel your way round the "unconnected-tension, connected-no-tension" contradiction, and you can't imagine how that contradiction precludes such a logically inconsistent environment be programmed (a sure sign you don't understand it).

A deep irony, though, is that this thread is like the Duhem-Quine Thesis for thought experiments. If your auxiliary hypotheses are at fault (I suspect they are absent) then your thought experiment doesn't work. It also refutes empiricism.

But sure, I'll go away as you command. Have been called "stupid" often enough here.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum