-

Inis

243No one would talk about views in, say, quantum mechanical interpretations this way so doing so here frankly sounds stupid. — MindForged

Inis

243No one would talk about views in, say, quantum mechanical interpretations this way so doing so here frankly sounds stupid. — MindForged

And, you call me "stupid"?

— Inis

— SophistiCatI have to say, you leave me little choice. — SophistiCat

If you have nothing new to add, perhaps seek a different thread. — Arkady

Yes indeed, people who can't comprehend Galileo's thought experiment, call me "stupid" and tell me to "seek a different thread".

Oh, to be in the presence of those with bigger brains than Galileo! -

MindForged

731I didn't at all comment in Galileo. What I called stupid was your insistence in childishly declaring the most held philosophical position on the matter as being "objectively" false as if it were just an obvious and incontestable thing to say. You are proving yourself not to be a serious person.

MindForged

731I didn't at all comment in Galileo. What I called stupid was your insistence in childishly declaring the most held philosophical position on the matter as being "objectively" false as if it were just an obvious and incontestable thing to say. You are proving yourself not to be a serious person. -

Arkady

768

Arkady

768

Not something I ever claimed. But the mere fact that we're discussing the wrongness of Aristotelian physics means that very smart people can sometimes go wrong. And I'll say one last time: just because someone disagrees, it doesn't mean they don't comprehend. You can stamp your feet all you want, but all you're doing is coming across as looking very juvenile. So, I'm done with you.Oh, to be in the presence of those with bigger brains than Galileo! — Inis -

SophistiCat

2.4kI largely agree with your treatment of this question, Sophisticat. However, the above assumption (i.e. that the falling bodies behave as if they're separate bodies until the string is taut) seems debatable to me: as the weights were connected by the tether prior to their being dropped, they've always been "one body," and thus it could be argued that the composite body comprising the two weights plus tether would always fall faster than either body alone, given that they've always been one object for the purposes of this experiment. — Arkady

SophistiCat

2.4kI largely agree with your treatment of this question, Sophisticat. However, the above assumption (i.e. that the falling bodies behave as if they're separate bodies until the string is taut) seems debatable to me: as the weights were connected by the tether prior to their being dropped, they've always been "one body," and thus it could be argued that the composite body comprising the two weights plus tether would always fall faster than either body alone, given that they've always been one object for the purposes of this experiment. — Arkady

Aristotle, even as Galileo presents him in his dialogue, talks about "natural motion," which apparently is a free fall through some medium, such as air or water (neither Aristotle nor Galileo would contemplate vacuum). But in Galileo's setup, whenever the two bodies interact (the lighter body retards the motion of the heavier body), each body, when considered individually, is being acted upon by the other, and therefore is not in "natural motion." The entire system of two tethered bodies can (in Newtonian hindsight) be seen as one body in free fall, but neither one of the two bodies is in free fall when they interact.

So we can quibble over whether tethered bodies constitute one body, but the important thing is whether they constitute two independently falling bodies. If they don't, as Galileo's thought experiment requires, then Aristotle's law does not apply.

An interesting side note to all of this is that, if Aristotelian physics (or, at least the part of the theory which posits that heavier objects fall faster than light ones) really does imply a contradiction, one must reach the modal conclusion that there are no possible worlds in which heavier objects accelerate faster than light ones under the force of gravity alone! Intuitively speaking (for my intuition, anyway), it seems odd to put such a seemingly contingent physical fact on par with blatant contradictions such as square circles, or objects which are both red all over and green all over, etc. — Arkady

We don't even have to consider alternative physics, because Galileo gets the actual physics wrong. Bodies falling in a medium do not fall with the same speed. Now, Galileo surely realized this (as did Aristotle - he has a number of formulations of his law, some of which account for and even appeal to this fact), so he inserts a proviso that the bodies should be of the same material or the same specific weight. But this doesn't quite salvage his argument: a wood chip will fall slower than a log. And besides, this proviso does no work in the logic of his thought experiment, so it is irrelevant.

Galileo obtains the right result in a vacuum, in uniform gravity - thanks to the fact that gravitational mass is the same as inertial mass. But I don't see how this result can be obtained from a priori considerations. It was considered contingent enough for scientists in the 20th century to conduct sensitive experiments in order to test it. It is a generic consequence of Einstein's General Relativity, but that theory is not a priori either. -

SophistiCat

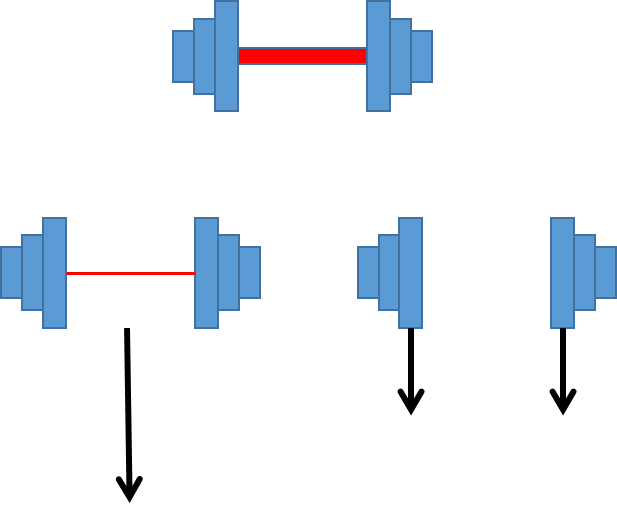

2.4kHere is a better (IMHO) refutation of Aristotle through thought experiment. Consider a dumbbell:

SophistiCat

2.4kHere is a better (IMHO) refutation of Aristotle through thought experiment. Consider a dumbbell:

Let's take two such dumbbells. On one of them we will replace the connecting rod with a hair-thin wire, and on the other we will remove the rod altogether. Now let's drop these two "dumbbells" side by side. According to Aristotle, the two unconnected weights should drop with the same speed - so far so good. But the still connected dumbbell, simply by virtue of being individuated as one body with twice as much weight as either of the free weights, should drop much faster - twice as fast, if we take Aristotle's strongest formulation of his law*.

Unlike in Galileo's thought experiment, there is no logical reductio here. But the situation is physically implausible, because as long as the connecting wire is not stressed (and it need not be in this experiment), there is practically no difference between a "dumbbell" connected with a wire and a pair of identical unconnected weights.

* This is somewhat unfair to Aristotle, because in one of his more careful formulations, he says basically that ceteris paribus, the heavier body falls faster than the lighter. Here ceteris is most definitely not paribus. -

Arkady

768

Arkady

768

In thinking about this topic recently, an ill-formed thought has been niggling in the back of my mind that there is something logically suspect about being able to disprove a supposedly contradictory statement (or a statement which implies a contradiction) through empirical means. Even if one holds the view that Artistotelian physics can be disproven a priori through thought experimentation, I doubt anyone would object that it can also be experimentally disconfirmed. So, empiricism and pure rationality would each be sufficient, but unnecessary, for such a disproof.Unlike in Galileo's thought experiment, there is no logical reductio here. — SophistiCat

Prima facie, this seems an unseemly mixing of the logically necessary (which would pertain to contradictions) and the logically contingent (which would pertain to empiricism). Are there any other logically necessary statements which are subject to empirical testing? -

SophistiCat

2.4kI don't know. It seems to me that only a defeasible statement can be meaningfully tested. How do you test a tautology (or a contradiction)?

SophistiCat

2.4kI don't know. It seems to me that only a defeasible statement can be meaningfully tested. How do you test a tautology (or a contradiction)?

I am familiar with this thought experiment, but not well-versed in its detailed treatment in the literature. I wonder how much of a point of contention this particular issue is. — Arkady

There seem to be quite a lot of references to the thought experiment in the literature - mostly it is (quite extensive) literature on thought experiments in general, but there are some specific examinations of Galileo's thought experiments, including some critical ones.

I found this paper interesting: D Atkinson, J Peijnenburg, Galileo and prior philosophy (2004)

They argue against the idea that Galileo succeeded in giving, in J. Brown's words, a "destructive" (against Aristotle's law of motion) and a "constructive" (in favor of Galileo's alternative) logical argument. Interestingly, they point to case where Aristotle happens to be right! It is the case of terminal velocity, which, under some conditions and idealizations, is directly proportional to the mass of the falling body. And yet Galileo would have it that this is logically impossible. How could that be?... -

Arkady

768

Arkady

768

I agree. It would be a peculiar situation, to say the least, if a logical truth could be put to an empirical test (as Aristotelian physics can be).I don't know. It seems to me that only a defeasible statement can be meaningfully tested. How do you test a tautology (or a contradiction)? — SophistiCat

Oh, I know...I was referring specifically to the one object/two object dispute, and how the nature of the tether (e.g. rigid vs. slack) affects the parameters of the thought experiment.There seem to be quite a lot of references to the thought experiment in the literature — SophistiCat

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum