-

fdrake

7.2kCalling the ready to hand 'autopilot' or flow implies suggests, even if you dont mean it that way, that objects 'in themselves' are there and we are simply not paying attention to them when we are focusing on a task. But this isn't how Heidegger understands the distinction between ready to hand and present to hand. The present to hand does not stand on equal ontological footing with the ready to hand. It's a derivative and impoverished mode of the ready to hand for Heidegger. . It s not that in pointing out an object we are attending to something extra, something we ignored during our labors. The opposite is the case. In moving from the ready to hand to the present to hand mode, we are ossifying, freezing , flattening and distorting the beings we are involved with. — Joshs

fdrake

7.2kCalling the ready to hand 'autopilot' or flow implies suggests, even if you dont mean it that way, that objects 'in themselves' are there and we are simply not paying attention to them when we are focusing on a task. But this isn't how Heidegger understands the distinction between ready to hand and present to hand. The present to hand does not stand on equal ontological footing with the ready to hand. It's a derivative and impoverished mode of the ready to hand for Heidegger. . It s not that in pointing out an object we are attending to something extra, something we ignored during our labors. The opposite is the case. In moving from the ready to hand to the present to hand mode, we are ossifying, freezing , flattening and distorting the beings we are involved with. — Joshs

Well of course the objects in themselves are there. And in Heidegger's analysis the present at hand is a degenerate case of the ready to hand. For the average kind of being that Dasein is supposed to represent, it's an appropriate move. But when specifically you're talking about contemplative labour, requiring that:

The present to hand does not stand on equal ontological footing with the ready to hand.

Doesn't make much sense. The transcendental priority of the ready to hand is legitimised through an appeal to everyday Dasein, not to specific modes of comportment. Dasein is a poor description of someone staring at a screen, someone feeling lactic acid in their muscles, someone contemplating the mysteries of life. -

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k

I forgot to say, I found an interesting paper recently here. It's quite a comprehensive 4E behavioural theory of consciousness. Though I have a sneaking suspicion it was written by @apokrisis.

Edit: the discussion about the agent 'factoring out' in tool use is very similar to how Heidegger's notion of the equipmental totality being 'free' or having its being 'freed' through circumspective concern (or intentionality in the diffuse sense) undermines the subject object distinction. It's also an interesting phenomenological corrective to correlationism 'putting the transcendental subject in the way of the world', so to speak. -

Joshs

6.6kWell of course the objects in themselves are there. — fdrake

Joshs

6.6kWell of course the objects in themselves are there. — fdrake

Let me flesh out what I mean by 'object in itself'. Forgive for quoting myself from an earlier comment on this thread.

I wrote " I read Heidegger as saying that that the idea of the present to hand object is a contrivance. In 'What is a thing' he talks about how it has become ingrained among people in the modern era to assume that self-identical persisting objects with attributes and properties exist , independent of the activities, thinking and purposes of individuals who encounter them. He calls this the "natural conception of the world". He goes on to say that what people today assume as natural and universal was in fact an invention of the West , beginning with the Greeks, and would have been considered an alien notion to many cultures. Heideger argues that RAH (ready at hand) underlies the PAH(present at hand) conceptualization, as well as all other possible variations of it. Why can there not be an 'object in itself? Because the notion of 'in itself' for Heidegger already implies a self-transcendence. His whole project begins from rethinking the 'is', attempting to show us that the simple copula is not just an inert glue between subjects and objects, but transforms what it articulates. This is a strange notion, but the upshot is that to experience is to alter. The meaning of anything is in the way in which it is an alteration with respect to our current situation. To point to a moment of experience and say 'object' is to do violence to this dynamism at the heart of meaning by attempting to freeze what was mobile, and thus actively significant and relevant, and make it inert , dead, meaningless. This PAH thinking which underlies our logic and empirical science allows us to do many things, but runs the risk of making us forget its basis in pragmatic involvement with the world."

The transcendental priority of the ready to hand is legitimised through an appeal to everyday Dasein, not to specific modes of comportment. — fdrake

But all inauthentic modes of comportment for Heidegger belong to average everydayness, and there is no room for the present to hand in authentic Dasein.

Dasein is a poor description of someone staring at a screen, someone feeling lactic acid in their muscles, someone contemplating the mysteries of life. — fdrake

Why would contemplation, reflection, feeling be modes that require the notion of self-identical object-things for their unfolding? I should add that for Heidegger, in doing something like performing a formal logical proof it isnt even a question of abandoning heedfully concernful relevant comportment. There simply is no activity that doesnt presuppose such relevant relating to beings.

Heidegger talks about what it means to see something 'as' something: "In the first and authentic instance, this “as” is not the “as” of predication qua predication but is prior to it in such a way that it makes possible the very structure of predication at all. Predication has the as-structure, but in a derived way, and it has it only because the as-structure is predication within a [wider] experience. But why is it that this as-structure is already present in a direct act of dealing with something? The most immediate state of affairs is, in fact, that we simply see and take things as they are: board, bench, house, policeman. Yes, of course. However, this taking is always a taking within the context of dealing-with something, and therefore is always a taking-as, but in such a way that the as-character does not become explicit in the act. The non-explicitness of this “as” is precisely what constitutes the act’s so-called directness. Yes, the thing that is understood can be apprehended directly as it is in itself. But this directness regarding the thing apprehended does not inhibit the act from having a developed structure. Moreover, what is structural and necessary in the act of [direct] understanding need not be

found, or co-apprehended, or expressly named in the thing understood.

I repeat: The [primary] as-structure does not belong to something thematically understood. It certainly can be understood, but not directly in the process of focally understanding a table, a chair, or the like.

Acts of directly taking something, having something, dealing with it “as something,” are so

original that trying to understand anything without employing the “as” requires (if it’s possible at

all) a peculiar inversion of the natural order. Understanding something without the “as”—in a

pure sensation, for example—can be carried out only “reductively,” by “pulling back” from an

as-structured experience. And we must say: far from being primordial, we have to designate it as

an artificially worked-up act. Most important, such an experience is per se possible only as the

privation of an as-structured experience. It occurs only within an as-structured experience and by

prescinding from the “as”— which is the same as admitting that as-structured experience is

primary, since it is what one must first of all prescind from."(Logic,The Question of Truth,p.122)

And as Derrida showed better than Heidegger did, in the midst of our pointing at, labeling, formalizing the world into thingly objects(res extensia) that we say are 'simply there', we are unknowingly remaining within radically contextual relating. This doesnt make the concept of an object 'false', it makes it a notion that doesn't fully understand the dynamics of its structuration with respect to the phenomenal unfolding of experience.

IS there such a thing as a hammer? Yes, but not as a meaning that adheres in itself independent of what we are doing with it, why we are accessing it. And furthermore, just staring at it amounts to staring at something that only remains the same by transforming its specific sense for us in subtle ways every moment of our apprehension of it. To be an 'it' of any kind is always to be a certain kind of change. To continue to be that 'it is to continue to change in a certain subtle kind of way that we naively call 'self-identical persisting'. -

Joshs

6.6kWhat is an example of this "not as good" way of thinking he labels "present-at-hand"? Is it literally just Descartes sitting in his room, ruminating about metaphysical matters a priori? Does it have to touch a "real world application" for it to be considered the "good" ready-at-hand? — schopenhauer1

Joshs

6.6kWhat is an example of this "not as good" way of thinking he labels "present-at-hand"? Is it literally just Descartes sitting in his room, ruminating about metaphysical matters a priori? Does it have to touch a "real world application" for it to be considered the "good" ready-at-hand? — schopenhauer1

In my view, there are lots of things Heidegger didn't make clear about the limits of science with regard to his notion of the present to hand. For one thing, his critique of science should really have clarified itself as a critique of a certain era of scientific thinking that most scientists, especially those in the hard sciences, remain within. But science's understanding of itself changes over the centuries.

This brings up a number of questions. In what ways does one's philosophical understanding of the nature and genesis of mathematics and logic affect how one uses such tools?There are mathematical platonists(Roger Penrose) and social constructionists(Arthur Fine) within the scientific community these days, yet both groups continue to rely on logic and mathematics. I think the difference between these groups is in how they interpret the meaning of their empirical results, as well as how s scientific method operates.The social constructionist will argue that mathematics doesnt give us a mirror of nature, and that it wasn't divinely ordained to fit the world. It is, instead, just a useful tool of language. Heidegger would mostly agree with the social constructionist.

As a semi-Heideggerian myself, the way I see present to hand theoretical concepts and mathematical schemes is that they are abstract devices whcih are designed to be general enough in their meaning as to mask the differences from person to person, and from moment to moment, in the meaningful sense that we get from them. Planes stay up in the air despite the fact that there is a certain play in the engineering language we rely on to build them.

As I write these lines on this page right now I could treat the letters and words in a present to hand way by believing that I perceive the meaning of each of them as bits of self-contained data, If I'm a Kantian I will believe that the data in and of itself doesnt form conceptual meaning until I as subject construct such meaning out of the data, but this would remain present to hand for Heidegger. Understanding the text in a ready to hand way, I perceive each letter and word as framed by and emerging out of the context of the ongoing meaningful thematical background, in Wittgensteinian fashion to some extent. So I don't first register the words in terms of some general dictionary definition and then connect them to the current narrative, Accessing some generic present to hand definition of the words would be a secondary, derived act. And in reading the same word over and over again, it is not the identical meaning that comes back to me but a meaning that is very subtly changing its sense in accordance with the subtle changes in the context of my activity of thought.( the major challenge here is to understand how something we perceive or think can appear to remain identical to itself over time not just in spite of, but because of its moment to moment changes in meaningful sense)

Basically, converting the present to hand back to the ready to hand doesn't require that we abandon logic, math and theory. It is a matter of enriching our thinking in the following way.

Whenever we are tempted to perceive a meaning as a 'thing-object' , a persisting self-identity,

we can make note to ourselves that what we are really encountering when we take something 'as' something-in-itself is a "confrontation that understands, interprets, and articulates, [and] at the same time takes apart what has been put together." Transcendence locates itself in this way within the very heart of the theoretical concept. Simply determining something AS something is a transforming-performing. It "understands, interprets, and articulates", and thereby "takes apart" and changes what it affirms by merely pointing at it, by merely having it happen to continue to 'BE' itself from one moment to the next.

In a way, this is a subtle modification of the usual way of treating objects. For everyday purposes it wont alter our comportment toward the world very much. Realizing that the allegedly persistng self-identicality of a thing only remains the 'same' by very slightly changing its sense in alignment with our unfoldling context of activity and purposes wont make the apparent moment to moment intelligible stability of our world collapse into chaos. But it may make the world appear a bit less arbitrary than it otherwise would. It reminds us that what we really want when we reflect creatively is not to nail down a self-identical content, but to find in the ongoing and unceasing flow of experiential change thematic unities and regularities -

ghost

109To point to a moment of experience and say 'object' is to do violence to this dynamism at the heart of meaning by attempting to freeze what was mobile, and thus actively significant and relevant, and make it inert , dead, meaningless. — Joshs

ghost

109To point to a moment of experience and say 'object' is to do violence to this dynamism at the heart of meaning by attempting to freeze what was mobile, and thus actively significant and relevant, and make it inert , dead, meaningless. — Joshs

This ignores why we evolved to do such a thing in the first place. Such 'violence' is necessary for our survival and sanity. Who's willing to deny that our thinking is an organization of chaos? Some philosophers want to call the organizing concepts 'real' and others want to call the chaos 'real.' Still others prefer to call the mundane organized chaos 'real.' Yet others question the importance of the game of deciding what is 'real' in some lusted-after context-independent sense of 'real.'

The penultimate perspective is great for practical life. The last perspective is good for chatting with philosophers. -

fdrake

7.2kHeidegger talks about what it means to see something 'as' something: "In the first and authentic instance, this “as” is not the “as” of predication qua predication but is prior to it in such a way that it makes possible the very structure of predication at all. Predication has the as-structure, but in a derived way, and it has it only because the as-structure is predication within a [wider] experience. But why is it that this as-structure is already present in a direct act of dealing with something? The most immediate state of affairs is, in fact, that we simply see and take things as they are: board, bench, house, policeman. Yes, of course. However, this taking is always a taking within the context of dealing-with something, and therefore is always a taking-as, but in such a way that the as-character does not become explicit in the act. The non-explicitness of this “as” is precisely what constitutes the act’s so-called directness. Yes, the thing that is understood can be apprehended directly as it is in itself. But this directness regarding the thing apprehended does not inhibit the act from having a developed structure. Moreover, what is structural and necessary in the act of [direct] understanding need not be — Joshs

fdrake

7.2kHeidegger talks about what it means to see something 'as' something: "In the first and authentic instance, this “as” is not the “as” of predication qua predication but is prior to it in such a way that it makes possible the very structure of predication at all. Predication has the as-structure, but in a derived way, and it has it only because the as-structure is predication within a [wider] experience. But why is it that this as-structure is already present in a direct act of dealing with something? The most immediate state of affairs is, in fact, that we simply see and take things as they are: board, bench, house, policeman. Yes, of course. However, this taking is always a taking within the context of dealing-with something, and therefore is always a taking-as, but in such a way that the as-character does not become explicit in the act. The non-explicitness of this “as” is precisely what constitutes the act’s so-called directness. Yes, the thing that is understood can be apprehended directly as it is in itself. But this directness regarding the thing apprehended does not inhibit the act from having a developed structure. Moreover, what is structural and necessary in the act of [direct] understanding need not be — Joshs

Yes. There is a distinction in Heidegger between propositional/predicative/apophantic as-structures and primordial/hermeneutic as structures. I know why Heidegger wants to move from the propositional as-structure to the hermeneutic as-structure, because one is transcendentally prior to the other; in the sense of existential understanding. Taking the categories and applying them to an existentielle understanding; an actual self aware comportment rather than a formally indicated synthesis of the transcendental structure of the self aware comportment; I think you'll see that it whether it makes sense to emphasise the transcendental priority of the hermeneutic-as structure and thus treat the apophantic as structure as a degenerate case turns on whether one is considering the coupled operation of the two in a self aware (reflective) comportment; when the comportment itself is thematised; or whether the transcendental structure of Dasein is thematised. Transcendental hierarchies don't remove ontic feedback loops.

Or, prosaically, forum Heideggerians (sorry, you included in these posts) never learn to apply the methodology to other things. This is why everything ends up in a discussion of the transcendental constitution of the subject in Heidegger, rather than... y'know. Talking about reflection on its own terms.

You will say 'but I am talking about reflection on its own terms! Because the formal structure implicates...' - take off the Heidigoggles for a second and constrain the space of inquiry. Be inspired by his methodology and terms rather than his conclusions.

Another way of putting it; the present at hand has interesting ontical relations with the ready to hand. Instances of the apophantic-as relating to the hermeneutic-as can have much different ontic structures; they can be in a feedback loop, one can pivot from one to the other giving life to 'ossified flesh'; except it was never ossified to begin with. The emaciated skeletal structure of the subject Dasein is is not a full account of human being; it falls silent on the specifics by design. -

ghost

109

ghost

109

I repeat: The [primary] as-structure does not belong to something thematically understood. It certainly can be understood, but not directly in the process of focally understanding a table, a chair, or the like.

Acts of directly taking something, having something, dealing with it “as something,” are so

original that trying to understand anything without employing the “as” requires (if it’s possible at

all) a peculiar inversion of the natural order. Understanding something without the “as”—in a

pure sensation, for example—can be carried out only “reductively,” by “pulling back” from an

as-structured experience. — Joshs

Great quote. I agree, and it's great to point out that pure color or pure tone are constructions. But we can also defend the utility of such choices. They weren't a madman's ravings. They were presumably inspired by noticing that humans have eyes and ears. Let experts jump in, but even a non-expert like myself can pretty safely assume that the brain synthesizes messages from the sense-organs into the world as we experience it.

[EDIT]

Those who started talking in terms of pure sensation were self-consciously analyzing 'being-in-the-world' with a particular purpose in mind. They didn't need to emphasize 'being-in-the-world.' I'm not saying that they noticed everything that Heidegger pointed out in his works, but I am saying that they had some version of pre-theoretical experience. They knew that their constructions were artificial. They came up with them in the first place. -

Joshs

6.6kThis ignores why we evolved to do such a thing in the first place. — ghost

Joshs

6.6kThis ignores why we evolved to do such a thing in the first place. — ghost

What do practical engagement . usefulness and achievement require? It used to be believed by most philosophers and scientists that the universe was a puzzle with fixed rules to be solved. More recently, we came to believe that knowledge of the world was not a matching of inner theory with outer independent reality, but a co-construction of a self-transforming universe. To discover the rules of the world was to invent a means of interacting with the world in adaptive ways. In this view, objects are contingent and temporary products of subject-object interaction.Heidegger is not far from this view. He just wants to clarify that they are even more temporary than we think. His approach doesn't abandon us to chaos. On the contrary, it show the arbitrariness in fixing objects as self-identities with attributes and properties, and offers a less arbitrary alternative thinking .

. -

ghost

109

ghost

109

Heidegger is a great philosopher. But like many great philosophers he emphasizes one important theme at the expense of other important themes.

FWIW, the 'co-construction of a self-transforming universe' is something I understand pretty well. I've argued for that myself in more metaphysical moods. We can even call that the 'speculative' truth.

...everything depends on grasping and expressing the ultimate truth not as Substance but as Subject as well.

The living substance, further, is that being which is truly subject, or, what is the same thing, is truly realised and actual (wirklich) solely in the process of positing itself, or in mediating with its own self its transitions from one state or position to the opposite. As subject it is pure and simple negativity, and just on that account a process of splitting up what is simple and undifferentiated, a process of duplicating and setting factors in opposition, which [process] in turn is the negation of this indifferent diversity and of the opposition of factors it entails. True reality is merely this process of reinstating self-identity, of reflecting into its own self in and from its other, and is not an original and primal unity as such, not an immediate unity as such. It is the process of its own becoming, the circle which presupposes its end as its purpose, and has its end for its beginning; it becomes concrete and actual only by being carried out, and by the end it involves.

...

What has been said may also be expressed by saying that reason is purposive activity. — Hegel

Note the repetition in our 'speculative truth' of metaphysics at its most grandiose. And what was Hegel concerned with? Basically religion. Philosophy is just religion done scientifically for Hegel.

Now maybe we have a twist where history never goes anywhere to die but just keeps leaping into the unknown. And I find it plausible that 'forms of life' are neither predictable nor stable.

Note also the for-dummies version: reason is activity with a purpose. It is a directed doing. Is that what's left when the holy smoke clears?

It's not that the speculative truth of Heidegger/Hegel can't be defended. But it's a questionable leap from phenomenology to newfangled Hegel. If we criticize artificial constructions with even more grandiose artificial constructions, ...

Finally I admit that this is largely a matter of taste or fashion. Maybe I've put my velvet sportcoat in the closet for now and grabbed my Carharrt chore coat for some variety.

Note for wearers of the chore coat who are curious about Heidegger:

Ontology : Hermeneutics of Facticity is a genuine pleasure to read. It's short, focused on the good stuff, and beautifully translated.

https://books.google.com/books?id=I9vsCQAAQBAJ -

Janus

17.9kPut differently, isnt it possible to to talk philosophically about the way that our moment to moment relation to the world and to our self transforms the nature of both the subjective and objective side of experience, without having to be accused of falling back into the same trap one is trying to critique? — Joshs

Janus

17.9kPut differently, isnt it possible to to talk philosophically about the way that our moment to moment relation to the world and to our self transforms the nature of both the subjective and objective side of experience, without having to be accused of falling back into the same trap one is trying to critique? — Joshs

You seem to be referring here to phenomenological practice The best we can do is to articulate how our lives seem to us, in the most open and general sense we can discover. The "traps" are to be found along the two opposite vectors of over-objectivification and over-subjectivification. I see it as an ultimately pragmatic endeavour; the only "truths" consist in the most-informed individual reasonableness and responsibility and the inter-subjective consensus they may lead to.

I see the the articulations of thinkers like Husserl and Heidegger as the direct continuation of the tradition of mathematical thought. Their formulations ARE a form of mathematics in the most sweeping sense. They are what mathematics had to become. — Joshs

I don't think this is a good analogy since mathematics is strictly rule-based and phenomenological inquiry is not. There are elements of art in mathematics but it is ultimately a science, just as there are elements of science in phenomenology, but it is ultimately an art, as Heidegger came to realize. -

ghost

109This doesnt make the concept of an object 'false', it makes it a notion that doesn't fully understand the dynamics of its structuration with respect to the phenomenal unfolding of experience. — Joshs

ghost

109This doesnt make the concept of an object 'false', it makes it a notion that doesn't fully understand the dynamics of its structuration with respect to the phenomenal unfolding of experience. — Joshs

Let's zoom in on this. When will we know that we have fully understood such a glorious thing as 'the dynamics of its structuration with respect to the phenomenal unfolding of experience'? Why would we need to know? This too would be scooped up in our directed doings. Or/also it would be the old metaphysickal seduction. The 'cool' teacher can wow his young students. They can slap some pseudo-scientific jargon on their preferences.

Attacks on science and correspondence are like attacks on dad for not actually being God but only a reliable, imperfect dad. It's not the the stoner son is talking nonsense. He's just mostly arguing against his own misunderstandings of pop. Pop never promised him a rose garden. To be fairer, I have seen some scientism. Some thinkers go too far in the other direction. -

Joshs

6.6kiWhen will we know that we have fully understood such a glorious thing as 'the dynamics of its structuration with respect to the phenomenal unfolding of experience.' Why would we need to know? — ghost

Joshs

6.6kiWhen will we know that we have fully understood such a glorious thing as 'the dynamics of its structuration with respect to the phenomenal unfolding of experience.' Why would we need to know? — ghost

I apologize for being lazy, but I've linked to an article I wrote in which I explain why I care about all this arcane stuff, and what relevance I think it has to the understanding of psychological phenomena such as affectivty , empathy, metaphor and social conditioning. https://www.academia.edu/38392024/Heidegger_Against_Embodied_Cognition -

Joshs

6.6k

Joshs

6.6k

So what is your definition of science that differentiates it from phenomenology? Here's my definition. Science is a name with changing meanings over time. It can be traced genealogically through cultural history in terms of these changing self-understandings which transform themselves in parallel with changes in philosophical worldviews over the past centuries . There is Greek science and philosophy, Scholastic science and philosophy, Enlightenment science and philosophy, Modernist science and philosophy, and post-modern science and philosophy. The difference within any era between the two is nothing that exists outside of that era, not science's understanding of its method, goals, tools, language. All of these are contingent. All that differentiates it from philosophy in any trans-historical sense is that it is more 'pragmatic'. And what does that mean? It uses a vocabulary that is less comprehensively self-examining. In one era that means it has privileged access to 'truth', in another that means it is a social construction which is as much art and politics as it is fact.there are elements of science in phenomenology, but it is ultimately an art. — Janus

mathematics is strictly rule-based and phenomenological inquiry is not. — Janus

Yes, but the reason that the rule-based nature of mathematics was so central to the philosophical projects of Aristotle, Descartes and Leibnitz was becasue the metaphysical grounding of logic and math was considered by them to also be 'rule-based'. They believed in a world that was grounded in such a way that it could be described as consisting of precisely defined rules of relationship.

Most philosophers no longer believe that the rules of relationship that ground ontology have fixed content. So the role that mathematics once served to model the metaphysical grounding of philosophy has been taken over by verbal description. Even when mathematical description is used, it is recognized as just being a species of language( all language implies a rule-based function) rather than a platonic essence. There is no longer agreement on the role of proof.

Husserlian phenomenology is very much rule -based, in that it consists of apodictic certainties. But these are no longer certainties of specific content, but certainties of the structural nature of temporal change. Husserl had no need to make use of mathematical description to model his grounding of phenomenology, since for him the mathematical, as a product of logic, is secondary to what grounds meaning.So my point is that the role that mathematics used to play in philosophy has been taken over

by a form of description that reflects the new way that ultimate precision is now understood. In that sense phenomenology, Nietzschean polemics, post structuralism , hermeneutics and pragmatism carry forward the tradition of mathemtics as the language of ultimate precision, but via a new type of discourse. -

ghost

109

ghost

109

I skimmed the paper. It's well written, and (FWIW ) I get the impression that you know what you are talking about. It is indeed thick with Heidegger and Derrida.

The paper does live at a high level abstraction. It'd be nice to hear how you'd apply your ideas to contemporary AI, just as Dreyfus once did.

Dreyfus claims that the plausibility of the psychological assumption rests on two others: the epistemological and ontological assumptions. The epistemological assumption is that all activity (either by animate or inanimate objects) can be formalised (mathematically) in the form of predictive rules or laws. The ontological assumption is that reality consists entirely of a set of mutually independent, atomic (indivisible) facts. It's because of the epistemological assumption that workers in the field argue that intelligence is the same as formal rule-following, and it's because of the ontological one that they argue that human knowledge consists entirely of internal representations of reality. — Wiki

It seems that Dreyfus was right. Or that Heidegger/Wittgenstein were right. Or that Hegel was right. Or that some 'idealist' was right.... -

ghost

109All that differentiates it from philosophy in any trans-historical sense is that it is more 'pragmatic'. And what does that mean? It uses a vocabulary that is less comprehensively self-examining. — Joshs

ghost

109All that differentiates it from philosophy in any trans-historical sense is that it is more 'pragmatic'. And what does that mean? It uses a vocabulary that is less comprehensively self-examining. — Joshs

Is that really the gist of 'pragmatic'? Why would people trust scientists more on certain issues? Certainly not because they are less comprehensively self-examining. They are reliable prophets and good at making stuff that gives us what we want.

If the distinction between philosophy and science is illusory or merely a useful fiction, then fine. But we can accuse any distinction of being a useful fiction. Unless the utility vanishes, the distinction won't either. -

ghost

109In that sense phenomenology, Nietzschean polemics, post structuralism , hermeneutics and pragmatism carry forward the tradition of mathemtics as the language of ultimate precision, but via a new type of discourse. — Joshs

ghost

109In that sense phenomenology, Nietzschean polemics, post structuralism , hermeneutics and pragmatism carry forward the tradition of mathemtics as the language of ultimate precision, but via a new type of discourse. — Joshs

I see what you mean. Our pragmatic, mundane ways of talking are cheap models, good enough for government work. But this is a stretched metaphor! Actual applied math is going nowhere. I think only someone who doesn't have their hands in the numbers would use that metaphor. -

Janus

17.9kSo what is your definition of science that differentiates it from phenomenology? — Joshs

Janus

17.9kSo what is your definition of science that differentiates it from phenomenology? — Joshs

All human disciplines and activities have their own methods and concerns and their unique evolutions of those and historical origins. Science, in its various guises, is concerned with understanding the cosmos, the natural world. Phenomenology is concerned with understanding the nature of human experience as such.

Regarding what you say about the reasons for mathematics being rule-based: I don't think it matters to the practice of mathematics whether you are a Platonist (as apparently many mathematicians still are) or a formalist or a contructivist or whatever. The practice of mathematics is rule-based; it is the rule-based discipline par excellence. You can't dispense with the rules and still claim to be doing mathematics.

Phenomenology, on the other hand, may be thought of as, and practiced as if it were, rule-based or it may not. I see poetry and literature, for example, or even the visual arts, as pursuits which it is possible to consider as forms of phenomenology. I don't see any reason to think that there are apodeictic certainties of the "structural nature of temporal change"; it all depends on perspective, unlike mathematics, which does not, as far as can see.

I mean, I suppose it could be said that sciences are phenomenological inasmuch as they study various kinds of phenomena; but phenomenology itself is concerned with human experience, with life as it is lived, specifically. -

Wayfarer

26kthe reason that the rule-based nature of mathematics was so central to the philosophical projects of Aristotle, Descartes and Leibniz was because the metaphysical grounding of logic and math was considered by them to also be 'rule-based'. They believed in a world that was grounded in such a way that it could be described as consisting of precisely defined rules of relationship.

Wayfarer

26kthe reason that the rule-based nature of mathematics was so central to the philosophical projects of Aristotle, Descartes and Leibniz was because the metaphysical grounding of logic and math was considered by them to also be 'rule-based'. They believed in a world that was grounded in such a way that it could be described as consisting of precisely defined rules of relationship.

Most philosophers no longer believe that the rules of relationship that ground ontology have fixed content. — Joshs

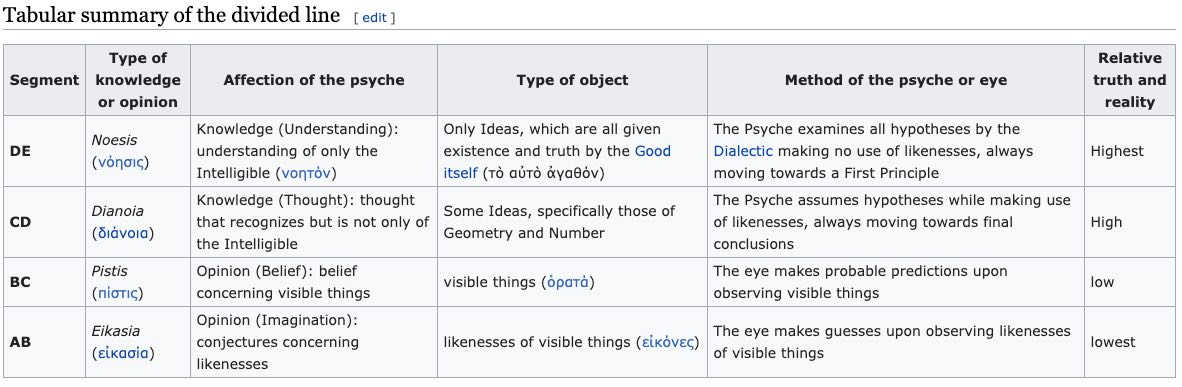

That's true, but consider it in the context of the Platonic epistemology of the Divided Line, from The Republic (reproduced here from Wikipedia):

I think the underlying motivation was the search for what is not contingent - necessary, or, if you like, eternal truths, as distinct from knowledge of the sensory domain, which was deprecated by the rationalist tradition. And that search or quest was in some important sense spiritual-religious - not in the sense of 'dogmatic belief' which likewise was classified by the philosophers as the domain of 'pistis' or 'doxa', but nearer to 'noesis', which is direct intuition or vision of the fundamental nature of reality. About which Thomas Nagel says:

Plato’s metaphysics was not intended to produce merely a detached understanding of reality. His motivation in philosophy was in part to achieve a kind of understanding that would connect him (and therefore every human being) to the whole of reality – intelligibly and if possible satisfyingly. He even seems to have suffered from a version of the more characteristically Judaeo-Christian conviction that we are all miserable sinners, and to have hoped for some form of redemption from philosophy.

So in the Platonic view, mathematical certainty was valuable, because less subject to change, so, further from the temporal, and nearer the eternal. And I think that's true of the classical or pre-modern tradition of philosophy, generally - that the truths of mathematics and logic were of a higher order than sensory truth, but not as of high an order as metaphysics, the 'first philosophy'. Whereas, since Galileo, the presumption of philosophy has shifted precisely to a 'detached understanding' in the sense of 'objectively absolute' - or as near to it as possible - and the 'reign of quantity'. But what has entirely gone, is the sense of there being a vertical dimension, some axis along which the judgement of what is 'higher', in a qualitative sense, is intelligible. -

Janus

17.9kWhat you say here is irrelevant to the point that @Joshs and I are discussing as I think is the remark by him that probably motivated your unnecessary didactic interjection:

Janus

17.9kWhat you say here is irrelevant to the point that @Joshs and I are discussing as I think is the remark by him that probably motivated your unnecessary didactic interjection:

Most philosophers no longer believe that the rules of relationship that ground ontology have fixed content. — Joshs

My point has been simply that mathematics, and science in general, considered as disciplines, are necessarily rule or procedure-based in ways that phenomenology is not. -

ghost

109Can anyone link the essay mentioned by OP? Or a synopsis of it. — Forgottenticket

ghost

109Can anyone link the essay mentioned by OP? Or a synopsis of it. — Forgottenticket

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Question_Concerning_Technology -

Joshs

6.6kScience, in its various guises, is concerned with understanding the cosmos, the natural world. Phenomenology is concerned with understanding the nature of human experience as such, with life as it is lived, specifically. — Janus

Joshs

6.6kScience, in its various guises, is concerned with understanding the cosmos, the natural world. Phenomenology is concerned with understanding the nature of human experience as such, with life as it is lived, specifically. — Janus

it sounds like you're saying there is a real realm of physical nature and a real realm of human subjective experience, or what we colloquially call 'phenomenological', and that the two are different in their contents and methods of study but equally primordial. We can study the nature of human experience naturalistically, using objective empirical methods of the social sciences, or phenomenologically, via non-empirical philosophical modes of inquiry.

The meaning of Husserl's phenomenology, which served as the jumping off point for Sartre, Merleau-Ponty and Heidegger, among others, is quite different from this colloquial understanding of phenomenological. As Dan Zahavi puts it " Husserl is not concerned with finding room for consciousness within an already well established materialistic or naturalistic framework. The attempt to do the latter assumes that consciousness is merely yet another object in the world. For Husserl, the problem of consciousness should not be addressed on the background of an unquestioned objectivism. Frequently, the assumption has been that a better understanding of the physical world will allow us to understand consciousness better and rarely, that a better understanding of consciousness might allow for a better understanding of what it means for something to be real.

The positive sciences are so absorbed in their investigation of the natural (or social/cultural) world that they do not pause to reflect upon their own presuppositions and conditions of possibility. For Husserl, natural science is (philosophically) naive. Its subject matter, nature, is simply taken for granted. Reality is assumed to be out there, waiting to be discovered and investigated. And the aim of natural science is to acquire a strict and objectively valid knowledge about this given realm. But this attitude must be contrasted with the properly philosophical attitude, which critically questions the very foundation of experience and scientific thought."

As Evan Thompson concurs "I follow the trajectory that arises in the later Husserl and continues in Merleau-Ponty, and that calls for a rethinking of the concept of “nature” in a post-physicalist way—one that doesn’t conceive of fundamental nature or physical being in a way that builds in the objectivist idea that such being is intrinsically or essentially non-experiential. We can see historically how

the concept of nature as physical being got constructed in an objectivist way, while at the same

time we can begin to conceive of the possibility of a different kind of construction that would be

post-physicalist and post-dualist–that is, beyond the divide between the “mental” (understood as

not conceptually involving the physical) and the “physical” (understood as not conceptually

involving the mental)."

So I would correct your claim that science is concerned with studying the natural world and phenomenology with the inner world of experience. Scientific approaches which are ensconced within a naive realist worldview believe that what they do is study the natural world. Empirical perspectives, such as 4ea(enactive, embodied, embedded extended affective), which have absorbed Husserl's lessons, do not make such claims for studying something called nature that can be thought independently of how the world appears for a subject. They don't study a natural world but an intersubjectively enacted world. And this isn't just psychologists I'm talking about but also biologists and physicists.

The practice of mathematics is rule-based; it is the rule-based discipline par excellence. You can't dispense with the rules and still claim to be doing mathematics. — Janus

How is mathematics rule-based? A mathematical operation assigns a procedure.These procedures organize actions in a particular way. That is how they act as rules. But constructivist mathematicians know that we cannot logically derive one procedure from another in terms of formal proof. Addition, multiplication and more sophisticated procedures ,therefore, act as all other linguistic concepts. They are formal abstractions. Their precision and power resides not in their being rules, because a rule in its essence is simply a way of proceeding. What give them their usefulness is the fact that they are supposedly unambiguously understood. The command 'move to your left' is a rule, but it is imprecise, subject to interpretation. What gives the meaning of a mathematical rule its suppose freedom from ambiguity? Mathematics, resting on logic, begins from the thought of a pure, ideal object , devoid of all content but that it exists in itself as object. This would seem to be obvious but the idea of pure object had to be formulated as such by the Greeks. Once the idea of ideal object was established , the possibility of calculation became possible. Calculation makes no sense without objectivity. Mathematical rules are operations on ideal objects. One counts two or three or four of 'this' . IF there is no self-identical 'this' to remain itself , then there is no basis for calculation. Even if one counts different things, one is abstracting a common property to be counted..

Husserl argues that what we actually experience are continuous flowing adumbartions of perceptual modifications, aspects, variations, not objects in themselves. We synthesize the idea of an object out of this constantly changing flow of experience, but we never end up with a simple conceptual form, because it is in the nature of experiencing to continually modify itself. Our objects are relative , always incomplete , ongoing syntheses, They are ongoing activities of consciousness.

The supposed pure self-identicality of objects, the basis of the power and precision of math, is in fact a self-changing process instead of a solid fact.. Thus means that the rule-bound nature of math amounts to the assignment of a procedure of action whose dependability is no more assured than the stability of meaning of the objects it seeks to organize via its rule. so the most fundamental precision grounding phenomena of experience(including 'nature') inheres in a discourse that is indeed rule-bound(in that it prescribes a procedure of thought) but a rule that takes into account self-reflexively the self-transfomational nature of nature. That is to say, such a rule takes into acdcount that the irreducible basis of the world is not objects in themselves, but intentional activities of subject-object correlation. So we can see why recent philosophers are no longer interested in grounding or buttessing their theories in formal logic/mathematics.

They have found more clarifying discursive rules. -

Joshs

6.6kSince Galileo, the presumption of philosophy has shifted precisely to a 'detached understanding' in the sense of 'objectively absolute' - or as near to it as possible - and the 'reign of quantity'. But what has entirely gone, is the sense of there being a vertical dimension, some axis along which the judgement of what is 'higher', in a qualitative sense, is intelligible. — Wayfarer

Joshs

6.6kSince Galileo, the presumption of philosophy has shifted precisely to a 'detached understanding' in the sense of 'objectively absolute' - or as near to it as possible - and the 'reign of quantity'. But what has entirely gone, is the sense of there being a vertical dimension, some axis along which the judgement of what is 'higher', in a qualitative sense, is intelligible. — Wayfarer

Wouldn't that higher dimension still be operative for a Kantian and neo-Kantian empiricism? The 'reign of quantity' needs its proper form to organize it, otherwise it becomes blind. We laugh at the idea that the secret to the universe is the number 44, because it points to no organization, no gestalt to animate it meaningfully. Unlike classical and scholastic Platonism, Kantianism doesnt believe in an eternal content that mathematics can reveal to us, but it does believe in eternal form. In a way this leaves mathematics in a more subservient role than it played in earlier philosophical eras. For the eternal form that represents the Kantian ideal, and is manifested in the transcendental categories, is not something that any given mathematical structure can approximate. It is simply the formal idea of mathematical objectivity itself. -

waarala

97I think that for Heidegger ready-to-hand (worldhood) is l i f e, it is the Being of life. It is the basic or fundamental reality. It is like sense data for sensualists. It is something fundamental which is given to us. It is Heidegger's version of "historical materialism"? But just experiencing this given is not yet philosophy or philosophical reflection. Dasein/existence with its "sight" moving among ready-to-hand significances is the practical subject of life but it is not the philosophical subject (of life or Being and Time). "Ready-to-hand" is phenomenological-ontological existential-category, not anything that Dasein/existence encounters as such in the world. Existence encounters only "this table here to ..." and "that book there to ...", it doesn't encounter philosophical categories like "ready-to-hand", "concern", "temporality". I think this distinction (between ontical and ontological) is often forgotten (as though some (naive) "absorption" or "autopilot" or "flow" would be some ideal true authentic life experience, even though it could mostly be just blind and dull routine). Being and Time is about the whole structure of the "life", ready-to-hand-being is "only " the basic cell of this structure. It is the last analytical unit that can't be reduced any further ("I am therefore I think"). Unreflective practical dasein/existence is operating in this basic unit of life without being "conscious" (without being interested in) of various kinds of Beings and their phenomenal structures. For practical existence all Being is the same pragmatic-technical being.

waarala

97I think that for Heidegger ready-to-hand (worldhood) is l i f e, it is the Being of life. It is the basic or fundamental reality. It is like sense data for sensualists. It is something fundamental which is given to us. It is Heidegger's version of "historical materialism"? But just experiencing this given is not yet philosophy or philosophical reflection. Dasein/existence with its "sight" moving among ready-to-hand significances is the practical subject of life but it is not the philosophical subject (of life or Being and Time). "Ready-to-hand" is phenomenological-ontological existential-category, not anything that Dasein/existence encounters as such in the world. Existence encounters only "this table here to ..." and "that book there to ...", it doesn't encounter philosophical categories like "ready-to-hand", "concern", "temporality". I think this distinction (between ontical and ontological) is often forgotten (as though some (naive) "absorption" or "autopilot" or "flow" would be some ideal true authentic life experience, even though it could mostly be just blind and dull routine). Being and Time is about the whole structure of the "life", ready-to-hand-being is "only " the basic cell of this structure. It is the last analytical unit that can't be reduced any further ("I am therefore I think"). Unreflective practical dasein/existence is operating in this basic unit of life without being "conscious" (without being interested in) of various kinds of Beings and their phenomenal structures. For practical existence all Being is the same pragmatic-technical being.

The present-at-hand could be seen only as an extension of ready-to-hand. (Prior it has become pure theory of what is this? Thing is seen as fallen from the sky.) Present-at-hand has often its roots still in pragmatic-technical-being and it merely theorizes some ready-to-hand relations so that theoretical relations are consequently embedded as ready-to-hand relations. For example, (in our hyper modernized global world) "improving" some tool requires that its properties are analyzed "abstractly" so that the device would work optimally in so general circumstances as possible. Here some general abstract properties tend to replace the adaptation or customization to individual situations. When this new improved device is commonly deployed we have ready-to-hand-being which is actually in part orientating itself according to present-at-hand-being. The more some thing or "state of affairs" in general is adequate or "closer" (intrinsic) to some other, the more there is authentic ready-to-hand-being and the less there is abstract present-at-handness. Abstract generalization means the estrangement from the concrete self-hood i.e. being as appropriate as possible in its own context. Abstraction/generalization broadens (or eventually destroys) the context so that the "fulfillment of the sense" (phenomenological concept) is experienced only with regard to some general properties. Dasein/existence orients itself towards property-significance as present-at-hand theoretical reality. New model of hammer with new improved properties makes Dasein/Existence hammering in a certain way in all situations. -

Joshs

6.6kAbstraction/generalization broadens (or eventually destroys) the context so that the "fulfillment of the sense" (phenomenological concept) is experienced only with regard to some general properties. — waarala

Joshs

6.6kAbstraction/generalization broadens (or eventually destroys) the context so that the "fulfillment of the sense" (phenomenological concept) is experienced only with regard to some general properties. — waarala

But can generalization ever really destroy context?(I think of Derrida's famous adage 'there is nothing outside context'). Even if a concept is experienced only with regard to some general properties,

aren't these so-called general properties made relevant for an individual in relation to their particular contextual situation, without their being explicitly aware of this? In other words, is there any way to ever escape the particularizing effect of context, even when we lose sight of this? -

Wayfarer

26kMathematics, resting on logic, begins from the thought of a pure, ideal object , devoid of all content but that it exists in itself as object. This would seem to be obvious but the idea of pure object had to be formulated as such by the Greeks. Once the idea of ideal object was established, the possibility of calculation became possible. — Joshs

Wayfarer

26kMathematics, resting on logic, begins from the thought of a pure, ideal object , devoid of all content but that it exists in itself as object. This would seem to be obvious but the idea of pure object had to be formulated as such by the Greeks. Once the idea of ideal object was established, the possibility of calculation became possible. — Joshs

Indeed, and again, to refer to the Platonic epistemology, this is because mathematical and logical proofs are apodictic, immediately evident to the intellect, without reference to sensory perception. That was the reason why, for Greek philosophers, they belonged to a higher or different order to the sensible. And, as you imply, the contribution of Greek philosophy here is seminal.

A footnote, however, is the way in which Galileo interpreted the significance of dianoia. He too understood the sense in which mathematics captured a higher level of truth - 'the book of nature is written in mathematics' - but regrettably, the other, more noetic and aesthetic elements of Platonic philosophy were relegated to the domain of the 'secondary qualities' by virtue of their association with the mind.

Unlike classical and scholastic Platonism, Kantianism doesn't believe in an eternal content that mathematics can reveal to us, but it does believe in eternal form — Joshs

Does it? The categories, according to IETP, were adapted pretty well wholesale from Aristotle. I am interested in your comment that they can be equated with the forms.

Reality is assumed to be out there, waiting to be discovered and investigated. And the aim of natural science is to acquire a strict and objectively valid knowledge about this given realm. But this attitude must be contrasted with the properly philosophical attitude, which critically questions the very foundation of experience and scientific thought." — Joshs

:clap: :clap: :clap:

Naturalism: 'what you see out the window'. Phenomenology: 'you looking out the window'.

Great post, by the way. I really like the way you're developing these ideas. I have the Kindle preview of the Thomson book and am going to buy. -

waarala

97But can generalization ever really destroy context?(I think of Derrida's famous adage 'there is nothing outside context'). Even if a concept is experienced only with regard to some general properties, aren't these so-called general properties made relevant for an individual in relation to their particular contextual situation, without their being explicitly aware of this? In other words, is there any way to ever escape the particularizing effect of context, even when we lose sight of this? — Joshs

waarala

97But can generalization ever really destroy context?(I think of Derrida's famous adage 'there is nothing outside context'). Even if a concept is experienced only with regard to some general properties, aren't these so-called general properties made relevant for an individual in relation to their particular contextual situation, without their being explicitly aware of this? In other words, is there any way to ever escape the particularizing effect of context, even when we lose sight of this? — Joshs

This is precisely the problem here, it could be the problem of "fallenness". To be as close or adequate as possible to the matter or case itself. What is the true experience or description of something? Differentiation, not unification, would make something appear as itself. Nature of natural sciences would be the realm of the technical unification though. After all, Dasein/existence has a physiological body which is often a technical object. Here Dasein is in principle exchangeable with any other Dasein.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum