-

Terrapin Station

13.8kIn my experience in school, science and mathematics contexts often had no time for philosophy because a common approach was to simply not care about those sorts of issues. There was a purely pragmatic, instrumental approach most of the time--they were merely concerned with whatever worked, whatever accounted for data/observations, and whatever produced results in applied settings. Focusing on what was "really the case ontologically," how we could know certain things, etc. was seen as a waste of time that had no practical upshot.

Terrapin Station

13.8kIn my experience in school, science and mathematics contexts often had no time for philosophy because a common approach was to simply not care about those sorts of issues. There was a purely pragmatic, instrumental approach most of the time--they were merely concerned with whatever worked, whatever accounted for data/observations, and whatever produced results in applied settings. Focusing on what was "really the case ontologically," how we could know certain things, etc. was seen as a waste of time that had no practical upshot. -

Terrapin Station

13.8kThe etymology of "metaphysics," by the way, is simply that it was an untitled book placed after the book entitled "Physics" in Aristotle anthologies (this is going back to the first century CE or even the last century BCE). The subject matter was conventionally the subject matter of that book, the bulk of which was what we know call ontology, as well as "first principles."

Terrapin Station

13.8kThe etymology of "metaphysics," by the way, is simply that it was an untitled book placed after the book entitled "Physics" in Aristotle anthologies (this is going back to the first century CE or even the last century BCE). The subject matter was conventionally the subject matter of that book, the bulk of which was what we know call ontology, as well as "first principles." -

T_Clark

16.1kThat said, you'll occasionally get a science popularizer like Massimo Pigluicii or a Carlo Rovelli who argue for the necessity of philosophy in science, which is nice. — StreetlightX

T_Clark

16.1kThat said, you'll occasionally get a science popularizer like Massimo Pigluicii or a Carlo Rovelli who argue for the necessity of philosophy in science, which is nice. — StreetlightX

Carlo Rovelli has a great interview on "The Philosopher's Zone," a program from the Australian Broadcast Company. It was a couple of years ago. There was also a follow up interview by Tibor Molnar, an Australian philosopher. Here's a link to the Molnar interview. Down the page is also a link to the Rovelli one. About 30 minutes.

https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/philosopherszone/an-answer-for-carlo-rovelli-and-his-quantum-problem/8659546

Gregory Bateson put it best: "The would-be behavioural scientist who knows nothing of the basic structure of science and nothing of the 3000 years of careful philosophic and humanistic thought about man - who can define neither entropy nor sacrament - had better hold his peace rather than add to the existing jungle of half-baked hypothesis". How many here can talk of both entropy and sacrament? — StreetlightX

Agree completely about half-baked philosophy and how it undermines credibility, but Bateson's statement is bologna. I don't have to study 3,000 years of philosophy to understand humanity. -

T_Clark

16.1kWell, if you want to include epistemology in metaphysics then it is completely and utterly true, without controversy, that science has metaphysics, which was my original assertion in this thread. It seemed like, though I could be wrong, he took associating metaphysics with science as religious. (I am not quite sure what was going on there, since he didn't quite respond to me). But if he is taking epistemology to be a part of metaphysics, I can't see how metaphysics could possibly be problematic when associated with science.. — Coben

T_Clark

16.1kWell, if you want to include epistemology in metaphysics then it is completely and utterly true, without controversy, that science has metaphysics, which was my original assertion in this thread. It seemed like, though I could be wrong, he took associating metaphysics with science as religious. (I am not quite sure what was going on there, since he didn't quite respond to me). But if he is taking epistemology to be a part of metaphysics, I can't see how metaphysics could possibly be problematic when associated with science.. — Coben

Whether or not you include epistemology in metaphysics, it is still philosophy and it's at the heart of science. -

T_Clark

16.1kPeople tend to learn things in the wrong order. Theory follows practice, and not the other way around. That is why you better get lots of work experience in your field first, before even getting a degree. The other way around will often make you sound like an arrogant prick who seeks to "skip the hard part". — alcontali

T_Clark

16.1kPeople tend to learn things in the wrong order. Theory follows practice, and not the other way around. That is why you better get lots of work experience in your field first, before even getting a degree. The other way around will often make you sound like an arrogant prick who seeks to "skip the hard part". — alcontali

Good post. -

T_Clark

16.1kwhen while studying general relativity we are told that matter tells spacetime how to curve and the curvature of spacetime tells matter how to move, it's very easy to start reifying spacetime as a concrete entity — leo

T_Clark

16.1kwhen while studying general relativity we are told that matter tells spacetime how to curve and the curvature of spacetime tells matter how to move, it's very easy to start reifying spacetime as a concrete entity — leo

People often call things "reification" as a way of undermining the legitimacy of an idea. Spacetime is as real as gravity, electrons, and dog hair. There's a good argument to be made that calling something "dog hair" is also reification, but that will just make scientists even surer we are all boneheads. -

Streetlight

9.1k. I don't have to study 3,000 years of philosophy to understand humanity. — T Clark

Streetlight

9.1k. I don't have to study 3,000 years of philosophy to understand humanity. — T Clark

He didn't say you have to study all of it; just that you ought to know more than nothing about it. So some of it will do. Will try listen to the podcast when I have a moment; the Phil Zone stuff is usually pretty good. -

leo

882People often call things "reification" as a way of undermining the legitimacy of an idea. Spacetime is as real as gravity, electrons, and dog hair. There's a good argument to be made that calling something "dog hair" is also reification, but that will just make scientists even surer we are all boneheads. — T Clark

leo

882People often call things "reification" as a way of undermining the legitimacy of an idea. Spacetime is as real as gravity, electrons, and dog hair. There's a good argument to be made that calling something "dog hair" is also reification, but that will just make scientists even surer we are all boneheads. — T Clark

Sorry no, if I can make predictions as accurate as general relativity without using the concept of curved spacetime, I'm not gonna say that curved spacetime is as concrete as dog hair I feel with my hands. If I let a ball fall to the ground, I'm not gonna say it accelerates because it contains some substance called potential energy that gets converted into another substance called kinetic energy, cause I can't feel these substances either. Otherwise by that logic I can just say that unicorns are as real as dog hair because I can think about unicorns, it's just a matter of thinking about them and they become concrete, they exist! But then let's stop disrespecting or ridiculing people who believe in ghosts or in the afterlife, because it's concrete to them just like curved spacetime is to you. -

T_Clark

16.1kOtherwise by that logic I can just say that unicorns are as real as dog hair because I can think about unicorns, it's just a matter of thinking about them and they become concrete, they exist! But then let's stop disrespecting or ridiculing people who believe in ghosts or in the afterlife, because it's concrete to them just like curved spacetime is to you. — leo

T_Clark

16.1kOtherwise by that logic I can just say that unicorns are as real as dog hair because I can think about unicorns, it's just a matter of thinking about them and they become concrete, they exist! But then let's stop disrespecting or ridiculing people who believe in ghosts or in the afterlife, because it's concrete to them just like curved spacetime is to you. — leo

Are you saying that unicorns and ghosts are as real as spacetime? Also, I don't understand why you would feel the need to ridicule people who believe in ghosts or the afterlife anyway. Here we are whining about how scientists ridicule us about our beliefs. -

Deleted User

0Whether or not you include epistemology in metaphysics, it is still philosophy and it's at the heart of science. — T Clark

Deleted User

0Whether or not you include epistemology in metaphysics, it is still philosophy and it's at the heart of science. — T Clark

Agreed. I think there are a number of ways metaphysics is a part of science- in theory and practice. -

SophistiCat

2.4kDo scientists have an irrational bias against philosophy, specifically philosophy of science? Or am I not understanding an obvious truth, such as that science doesn't seem to have anything to do with philsophy of science? — Shushi

SophistiCat

2.4kDo scientists have an irrational bias against philosophy, specifically philosophy of science? Or am I not understanding an obvious truth, such as that science doesn't seem to have anything to do with philsophy of science? — Shushi

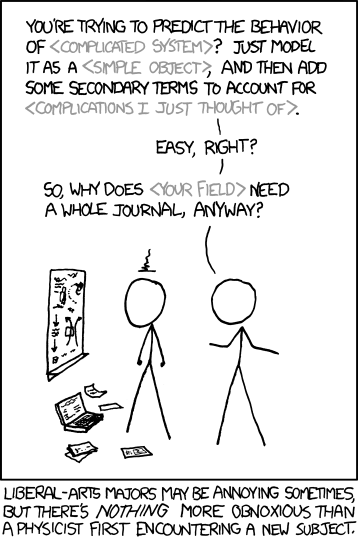

Well, Science Forums has an explicitly stated narrow focus and tight moderation, so the fact that your thread was closed immediately and the earlier thread was short-lived as well is not an indication of anything. However, it has been my experience that people with scientific and engineering background do often display little patience for and a good deal of prejudice against philosophy. Unsurprisingly, this is mainly seen among those who know little about the field, or worse, have distorted ideas about it.

For example, outside of its specialized usage, the word "metaphysics" can mean "abstract theory with no basis in reality" (OED), and historically it has often been associated with the irrational and the occult. Is it surprising that people who are into natural sciences would tend to be allergic to such a notion? You yourself have confessed to thinking that "it was just pure speculative talk and nonsense that anyone could make up" - before you learned a little more about what philosophy was really about. And, to be fair, a good deal of philosophy has been and still is "speculative talk and nonsense" - but not all of it, as you and I agree (although to my mind, Penrose and Polkinghorne offer examples of the more disreputable kind of "metaphysics").

No doubt, some of the prejudice comes from ignorance and the sort of arrogance that people who are accomplished in their field often display for other fields (here, of course, I am talking about people like Hawking and Krauss, not just random Science Forum posters, most of whom are not even scientists). Physicists might be especially guilty of this:

There have always been scientists with an interest in and a respect for philosophy. Off the top of my head, a few of the prominent working scientists are George Ellis, Sean Carroll, Anthony Aguirre - perhaps not surprisingly, all cosmologists. I could also think of some theoretical physicists. But it used to be - I don't know if things have changed in the recent decades - that philosophy was almost a taboo subject in science departments. David Albert, who earned his Ph.D. in theoretical physics in 1981, says that after he developed an interest in philosophy he almost got kicked out of the grad school when he said that he wanted to write his thesis on foundations of physics. In the end he was forced to do a thesis on a very technical, calculation-heavy subject picked for him by the department, but eventually, after working with Aharonov at the Tel Aviv University, he became one of the more prominent philosophers of physics. -

leo

882Are you saying that unicorns and ghosts are as real as spacetime? Also, I don't understand why you would feel the need to ridicule people who believe in ghosts or the afterlife anyway. Here we are whining about how scientists ridicule us about our beliefs. — T Clark

leo

882Are you saying that unicorns and ghosts are as real as spacetime? Also, I don't understand why you would feel the need to ridicule people who believe in ghosts or the afterlife anyway. Here we are whining about how scientists ridicule us about our beliefs. — T Clark

I don't ridicule people who believe in ghosts or the afterlife, but it's often what scientists do.

I'm saying that if you believe in curved spacetime, curved spacetime is as real to you as unicorns and ghosts are real to people who believe in them. While if you don't believe in unicorns or ghosts, they exist to you as an idea, just like curved spacetime exists to me as an idea.

It's also somewhat the way Einstein viewed it:

we have attempted to describe how the concepts space, time and event can be put psychologically into relation with experiences. Considered logically, they are free creations of the human intelligence, tools of thought, which are to serve the purpose of bringing experiences into relation with each other, so that in this way they can be better surveyed.

(in his book Relativity and the Problem of Space)

The only justification for our concepts and system of concepts is that they serve to represent the complex of our experiences; beyond this they have no legitimacy.

(in The Meaning of Relativity)

You imagine that I look back on my life's work with calm satisfaction. But from nearby it looks quite different. There is not a single concept of which I am convinced that it will stand firm, and I feel uncertain whether I am in general on the right track.

(in a letter to a friend in 1949)

He saw curved spacetime as a tool of thought, whose only legitimacy is to "represent the complex of our experiences". He didn't assume that curved spacetime was necessary to account for observations.

The geometry of space is not something that can be tested experimentally. For instance you can account for gravitational lensing by assuming that light travels in straight lines in curved space, or by assuming that light has a curved trajectory in flat space.

Poincaré understood that over a century ago already, here is what he said in his book Science and Hypothesis:

we could give up Euclidean geometry, or modify the laws of optics, and suppose that light is not rigorously propagated in a straight line. Euclidean geometry, therefore, has nothing to fear from fresh experiments.

no experiment will ever be in contradiction with Euclid's postulate; but, on the other hand, no experiment will ever be in contradiction with Lobachevsky's postulate.

It's a bit sad that these insights aren't found in the minds of most physicists and science enthusiasts today. -

leo

882I mean, a century ago scientists-philosophers like Einstein and Poincaré understood fundamental ideas about science and the concepts it uses that many scientists and teachers today do not understand, and then people who are curious about science do not understand them either. There are so many fallacies and misconceptions in recent educational materials, it took myself a great deal of time and effort to see through them and all the confusion it generates.

leo

882I mean, a century ago scientists-philosophers like Einstein and Poincaré understood fundamental ideas about science and the concepts it uses that many scientists and teachers today do not understand, and then people who are curious about science do not understand them either. There are so many fallacies and misconceptions in recent educational materials, it took myself a great deal of time and effort to see through them and all the confusion it generates.

Something has gone terribly wrong since then, my view is that in preferring mathematical elegance over intuitive simplicity, physicists of the 20th century have built theories that are much more complex than they need to be, and instead of rethinking the foundations they keep building on top of them and they have created a monster which has become almost inscrutable to philosophers, in which the motto is "shut up and calculate". So physics students have no time to philosophize, they have to learn all the intricacies to shut up and calculate properly, and by the time they become professional researchers they keep on making the monster grow, trying to unify its different parts by coming up with ever more complex concepts that encompass them.

I think most if not all of the great advances in science came from scientists who were also philosophers, or from chance discoveries. There is probably more to gain by thinking about and rethinking the foundations of fundamental physics that by continuing to develop the current theories, which in my view are stuck in an impasse of growing complexity and diminishing returns. -

T_Clark

16.1kI'm saying that if you believe in curved spacetime, curved spacetime is as real to you as unicorns and ghosts are real to people who believe in them. While if you don't believe in unicorns or ghosts, they exist to you as an idea, just like curved spacetime exists to me as an idea. — leo

T_Clark

16.1kI'm saying that if you believe in curved spacetime, curved spacetime is as real to you as unicorns and ghosts are real to people who believe in them. While if you don't believe in unicorns or ghosts, they exist to you as an idea, just like curved spacetime exists to me as an idea. — leo

Everything we know, everything we think is metaphorical. Spacetime is as real as gravity, inertia, atoms, countries, oceans, dog hair, and so on and so on. The world isn't split up into anything until we come along and do it. Everything is a reification. Why pick on spacetime? -

TogetherTurtle

353There would be no issue if they didn't make metaphysical claims about what's possible and what's not possible, what the world is and what it isn't, what we are and what we aren't, where we come from, where we are going, and then ridicule or attack people who disagree with their metaphysical claims because supposedly these people don't understand 'physics'. If they don't know about things outside of their area of expertise, it might be better if they didn't claim to know about them no? The worst part is they aren't even aware they're doing it, so fundamentally they don't even know the limits of their supposed area of expertise, and so they aren't experts about physics either, but they believe they are, and that cult is widespread. — leo

TogetherTurtle

353There would be no issue if they didn't make metaphysical claims about what's possible and what's not possible, what the world is and what it isn't, what we are and what we aren't, where we come from, where we are going, and then ridicule or attack people who disagree with their metaphysical claims because supposedly these people don't understand 'physics'. If they don't know about things outside of their area of expertise, it might be better if they didn't claim to know about them no? The worst part is they aren't even aware they're doing it, so fundamentally they don't even know the limits of their supposed area of expertise, and so they aren't experts about physics either, but they believe they are, and that cult is widespread. — leo

This sounds like more of a critique on human hypocrisy than a single group. I think it's inevitable for people to have misconceptions on ideas they don't know of or understand, especially when the outstanding members of a community misrepresent the actual ideals of a community.

I think @StreetlightX said it best-

It is really any surprise? Science forums regularly get inundated with hacks trying to use 'philosophy' to prove whatever pet theories they have about the universe, or else prove [major and well-acceped scientific theory] wrong in some manner or another. 'Philosophy' being whatever tripe said person thought of in the shower 20 mins ago. We get that shit on a semi-regular basis. Not to mention that philosophers - professional and amateur - are notoriously undereducated with respect to science. Science is right to be weary of philosophy. That said, you'll occasionally get a science popularizer like Massimo Pigluicii or a Carlo Rovelli who argue for the necessity of philosophy in science, which is nice. — StreetlightX

I think if we want to be respected, it's up to us to gain that respect. We can't count on outsiders to just give us the benefit of the doubt when everything they see says otherwise.

For a long time Philosophy has been cast aside by most. At least in America, they don't even teach it in school. (outside of the occasional reference to philosophers that may have inspired the founding fathers, of course.) If we want to change that, we have to prove that it's worth it to change that. We have to present what our findings contribute to humanity and show that we don't agree with those who would manipulate our work to accommodate their delusional world view.

It is hypocritical to have physics without metaphysics, but those who live hypocrisy don't realize they're living it. I would assume even you and I live some sort of hypocrisy. We have to rely on others to make us question things we take for granted. -

leo

882Everything we know, everything we think is metaphorical. Spacetime is as real as gravity, inertia, atoms, countries, oceans, dog hair, and so on and so on. The world isn't split up into anything until we come along and do it. Everything is a reification. Why pick on spacetime? — T Clark

leo

882Everything we know, everything we think is metaphorical. Spacetime is as real as gravity, inertia, atoms, countries, oceans, dog hair, and so on and so on. The world isn't split up into anything until we come along and do it. Everything is a reification. Why pick on spacetime? — T Clark

If that's the way you see it, then again by that logic unicorns and ghosts are as real as oceans and dog hair, just because we can think about them.

Reification is defined as treating an idea as a concrete thing. For instance a rock is a concrete thing, you can see it, you can touch it, even smell it or taste it. You can do that with dog hair too, and with ocean water. You can't do that with a country, but you can do it with concrete things that you define as part of a country, or with a part of a concrete map that you define as a country. You can't do that with inertia, or gravity, or spacetime. That's the distinction.

And when we talk of spacetime really curving, and when we say that planets (which are concrete things, we can at least see them) move the way they do because spacetime is curved, we're treating spacetime as a concrete thing, as if it was some concrete entity really curving, but spacetime is nowhere to be seen or touched, it's an idea that is defined from concrete things, or as Einstein put it it's a free creation of the human intelligence, a tool of thought, as opposed to, say, a rock.

If you don't want to make a distinction and remain consistent, you either have to treat every idea as a concrete thing (so a ghost is concrete like a rock because you think about it), or you have to treat every concrete thing as an idea (so a rock is an idea just like a ghost or a unicorn is). Otherwise if you want to make a distinction and you're treating an idea as a concrete thing then you're making the fallacy of reification.

I'm not necessarily picking on spacetime, I just think it's a good example, because it's a concept I struggled with for a long time precisely because teachers and physicists talked of it as if it was a concrete thing, precisely because they made that fallacy of reification, and I see that as a sign that philosophy is sorely needed in physics and more generally in science. But besides spacetime I could also pick gravity or energy or force or plenty of others.

To say for instance that gravity isn't a concrete thing isn't to say that we don't observe things falling to the ground, but it's a fallacy to say that things fall because of gravity: gravity is a summary or model of observations of concrete things, a thing falling to the ground is just an instance of what we call gravity, it is not caused by gravity, gravity isn't a concrete thing we have identified independently. Whereas if we see you pick up a stick and cut it in half, we can say the stick being cut in half was caused by you, since you are a concrete entity, you aren't just an idea. -

leo

882For a long time Philosophy has been cast aside by most. At least in America, they don't even teach it in school. (outside of the occasional reference to philosophers that may have inspired the founding fathers, of course.) If we want to change that, we have to prove that it's worth it to change that. We have to present what our findings contribute to humanity and show that we don't agree with those who would manipulate our work to accommodate their delusional world view. — TogetherTurtle

leo

882For a long time Philosophy has been cast aside by most. At least in America, they don't even teach it in school. (outside of the occasional reference to philosophers that may have inspired the founding fathers, of course.) If we want to change that, we have to prove that it's worth it to change that. We have to present what our findings contribute to humanity and show that we don't agree with those who would manipulate our work to accommodate their delusional world view. — TogetherTurtle

At some point people need to have a bit of intellectual integrity, they just have to look at the history of science and read papers of renowned scientists of the past to see that these scientists were also philosophers, and that philosophizing led them to their path of discovery. People keep talking about "the scientific method", "the scientific method" doesn't say what hypothesis ought to be formulated or how it ought to be tested, at that point philosophy enters the stage. Bridgman used to say there are as many scientific methods as there are individual scientists. If people won't acknowledge that, if they are not willing to make the effort to see the importance of philosophy in science, what do we have to prove and what can we prove to them? They are not willing to accept the proofs, they just want to stay in their ivory tower and think they are better than everyone else while they are actually poor scientists and more like parrots who regurgitate what they have rote-learned. -

TogetherTurtle

353If people won't acknowledge that, if they are not willing to make the effort to see the importance of philosophy in science, what do we have to prove and what can we prove to them? They are not willing to accept the proofs, they just want to stay in their ivory tower and think they are better than everyone else while they are actually poor scientists and more like parrots who regurgitate what they have rote-learned. — leo

TogetherTurtle

353If people won't acknowledge that, if they are not willing to make the effort to see the importance of philosophy in science, what do we have to prove and what can we prove to them? They are not willing to accept the proofs, they just want to stay in their ivory tower and think they are better than everyone else while they are actually poor scientists and more like parrots who regurgitate what they have rote-learned. — leo

This sounds, at least to me, like an "us versus them" argument. I think it may be time to step back and realize what team we're on.

We rely on the progress science makes to improve our lives. If that progress slows or even halts because of a flaw in their ideology, we will suffer. All mankind will suffer. Under the right circumstances, it could even result in the regression or even extinction of our species.

This, civilization, is a collaborative effort. We must all bring to the table what we have, because if everyone does, the rewards will be greater than anything we've given up. If we can fix something now that may cause problems later, it is our very purpose to do so. Even if you refuse to accept an apology, even if your disgust towards these people never fades, you must at least acknowledge that a world without them is a world you don't want to live in. -

Pattern-chaser

1.8kThat's where science leaves off in time.... :joke: — Coben

Pattern-chaser

1.8kThat's where science leaves off in time.... :joke: — Coben

Parsing error. No meaning detected. :confused: -

Constrained Maximizer

10"I do not like to suffer at all from what I call the German disease, an interest in philosophy"

Constrained Maximizer

10"I do not like to suffer at all from what I call the German disease, an interest in philosophy"

- James Watson -

Shushi

41This sounds, at least to me, like an "us versus them" argument. I think it may be time to step back and realize what team we're on. — TogetherTurtle

Shushi

41This sounds, at least to me, like an "us versus them" argument. I think it may be time to step back and realize what team we're on. — TogetherTurtle

Hi TogetherTurtle,

I think at this point of the discussion you seem to insinuate a belief that there aren't major issues with science, in that the philosophy community needs to do a better job at contributing to mankind, which philosophy hasn't been doing a good job in recent year which is why it has garnered a sort of status as a trivial discipline that is dead for the most part, which either philosophy has to be more like science in that it makes contributions that are equivalent to it (the sort contributions that science makes) or something else (which I'm trying to guess from your perspective at this point). Is this sort of accurate to your view? If not please correct me, and I do apologize if I am inaccurately portraying/strawmanning your position.

If that is your position, I think there is a sort of "talking past each other" going on here. Let me explain. The main focus on this thread is the recognition of something lacking in the scientific community, which examples of problems plaguing this community like pseudoscience and deceptive practices infiltrating scientific journals where there is an irreproducibility crises affecting the community, much of which simple tools of philosophy would take care of,

(such as scientists being formally trained to recognized the distinctions between the ethos, pathos and logos of an argument, the distinction between ontology and epistemology, the differences between inductive, deductive, and abductive arguments, or a valid or sound deductive argument or a strong or cogent inductive argument [which is essential when examining causation/correlation] knowing what the limits are of the scientific method, and learning simple epistemological tools [which is examining the theory behind and the making of the scientific method] such as Analytic A Priori [logical], A Priori Synthetic, A Posteriori Analytic [hypothetical], and A Posteriori Synthetic [empirical], and simple epistemological positions like evidentialism, reliabilism, pragmatism, presuppositionalism, fideism, positivism)

[which, having started off as a science major myself, I had originally pursued physics thinking that it was the best tool that described the world, as well as describe ultimate truth and reality, which after I have taken a side course in philosophy [mainly because thought that it would have been a free B], I had come to realize that I was mistaken in my initial belief, that what I was truly aiming for was not necessarily in physics, but it was in philosophy, which I found to be the case with many who do science, which is why I believe a basic 101 course of philosophy is important to all of those who want to do science, mainly so that many can recognize these distinctions between science and philosophy as well as the limits of science, in what it says and what it doesn't say, like the difference between a scientific fact vs a fact vs a concrete ontic object, or the distinctions between what a theory, scientific theory, hypothesis and a philosophical belief are]

Now, what is see Leo is arguing about, is also another problem that has been plaguing the scientific community (which has also affected his ability to be effective in science) which a large portion of the scientific community dogmatically impose a sort of perspective onto others in order for one to be accepted in the community and to receive tenor and recognition. This sort of view that Leo has an issue with is this sort of (epistemological) scientism and ontological naturalism (realism) perspective on what science is [which science just is the search for natural causes or explanations of phenomena which what is natural and physical are realities that are verifiable empirically with real world effects], as well as the inability for anyone to question some mechanisms that have been instituted ever since the mid 20th century. The issue is that much of these instituted limits are metaphysical arguments or philosophical in nature, and there is this sort of allergic reaction to philosophy, most in part due to the ignorance of what philosophy and metaphysics are, as SophistiCat has mentioned.

That's not to deny that there have been many who have questioned it for the wrong reasons such as trying to make science accept or include many ideas such as astrology, or ideas that aren't grounded in either empirical verification as well as being logically consistent, which what comes to my mind is the Kosol's Metaphysics thing. So to summarize, the scientific community does not need to throw away the baby with the bathwater, in that the baby, which is philosophy is actually essential to the growth of science, and although certain knowledge or expertise does not seem to necessary at all levels of science, (such as associates or bachelors undergrads in engineering, or basic physics or astronomy [who may be focused more on areas that require measurements and calculations and knowing some theories that are general to the work they do] vs post grad systems engineering, information expert analysts, theoretical physicists, cosmologists, etc)

Philosophy has made progress and continues to do progress such as the old guard that used to champion some forms of positivism or the verificationist principle, have in recent years been dispelled with from the works of Paul Benacerraf (significantly in the area of philosophy of mathematics in philosophy and science) or Alvin Plantinga.

Here are some neat videos that go more in depth on the progress of philosophy and if you're a visual learner like I am, a neat presentation on the importance/defense of philosophy.

and a sort of general overview of philosophy and science

-

unenlightened

10kBuilders also have a disdain for Architects, with their airy-fairy notions of form and function and beauty, and no proper understanding of brickwork. Let the brickies discuss trowel size and pointing finishes in peace, and the architects can discuss their rarified and impractical concerns amongst themselves elsewhere. Just don't expect a bricky to design your new house, even if he thinks he can.

unenlightened

10kBuilders also have a disdain for Architects, with their airy-fairy notions of form and function and beauty, and no proper understanding of brickwork. Let the brickies discuss trowel size and pointing finishes in peace, and the architects can discuss their rarified and impractical concerns amongst themselves elsewhere. Just don't expect a bricky to design your new house, even if he thinks he can. -

leo

882This sounds, at least to me, like an "us versus them" argument. I think it may be time to step back and realize what team we're on.

leo

882This sounds, at least to me, like an "us versus them" argument. I think it may be time to step back and realize what team we're on.

We rely on the progress science makes to improve our lives. If that progress slows or even halts because of a flaw in their ideology, we will suffer. All mankind will suffer. Under the right circumstances, it could even result in the regression or even extinction of our species. — TogetherTurtle

I don't see it as an us vs. them, to me science and philosophy are inseparable, and trying to separate them makes science a religion and philosophy something irrelevant to most people. I see the whole endeavor of making observations and thinking about them and interpreting them and comparing them and connecting them as both science and philosophy, they didn't use to be separate in the minds of people, but now they are for no good reason in my view, simply because of confusions and misconceptions.

So whatever progress is a result of what I would call science-philosophy, even scientists who say they despise philosophy make use of it in their research, they just don't realize it, but that means they are often not aware of their beliefs underlying their research. Also I disagree that what we call 'progress' necessarily improve our lives, it seems to me we're on a course towards destroying life on Earth all while reveling in the idea that we're making progress. Maybe if we thought more about what we are doing, rather than just keep on doing whatever we're doing, we wouldn't be going that way.

This, civilization, is a collaborative effort. We must all bring to the table what we have, because if everyone does, the rewards will be greater than anything we've given up. If we can fix something now that may cause problems later, it is our very purpose to do so. Even if you refuse to accept an apology, even if your disgust towards these people never fades, you must at least acknowledge that a world without them is a world you don't want to live in. — TogetherTurtle

I don't have a disgust for scientists, I have a disgust for the idea that thinking about what we are doing is useless, that it's useless to think about the meaning of what we're doing, to think about how certain the results we get are, to think about the beliefs and assumptions underlying what we do, to think about other world views we would get by picking other beliefs or assumptions, to think about the consequences of what we do. The idea that the only thing that's useful is to keep doing whatever we're doing because supposedly we're making Progress and supposedly we're getting closer to Truth and supposedly Science will solve all our problems. We might very well go on to destroy the world while being stuck in that cult. -

Terrapin Station

13.8k

Terrapin Station

13.8k -

leo

882"I do not like to suffer at all from what I call the German disease, an interest in philosophy"

leo

882"I do not like to suffer at all from what I call the German disease, an interest in philosophy"

- James Watson — Constrained Maximizer

That quote is from his paper "Biology: A Necessarily Limitless Vista".

I find it quite funny that in the very next paragraph James Watson engages in philosophy:

I should begin by saying what I mean by science. It is simply a method of trying to explain the animate and inanimate objects around us – or at least their reproducible parts, how the world works, and what it is made of. That is, what are sometimes called the laws of nature.

Then

A question I find more interesting than the abstract discussion of the limits to scientific knowledge is how far can you limit human curiosity? Are there ways of prescribing what humans think about?

then

life is organized solely around molecular structures that initially spontaneously came together to create the first form of life and which later evolved using natural selection into the extraordinary diversity of living organisms that now populate our planet.

We should thus accept the fact that we alone, without any help from the heavens, must organize our futures to the best of our abilities.

I guess he did suffer from that disease too, and the worst part is he didn't even know it. -

Shushi

41I wanted to just add this video on this recent movement that's been happening within science, that's looking to add and create new maths in order to better describe quantum mechanics and solve a lot of issues that have stagnated science (which I would include philosophy as not not just another factor to add, but the most important one as far as I can tell, since one would need to think between new and different mathematical models and approaches which may be informed by both epistemic and analytic inferences). Its provides interesting insights to the main subject of this thread esspecially since a lot of scientists today would call all these new mathematics and different metaphysical assumptions as too philosophical and off-putting,

Shushi

41I wanted to just add this video on this recent movement that's been happening within science, that's looking to add and create new maths in order to better describe quantum mechanics and solve a lot of issues that have stagnated science (which I would include philosophy as not not just another factor to add, but the most important one as far as I can tell, since one would need to think between new and different mathematical models and approaches which may be informed by both epistemic and analytic inferences). Its provides interesting insights to the main subject of this thread esspecially since a lot of scientists today would call all these new mathematics and different metaphysical assumptions as too philosophical and off-putting,

And this presentation from Sir Roger Penrose on the limitations of science in computations, current arithmetic and mathematic induction (and the relationship between mathematics, logic and philosophy and how advancements in those provides a proper metaphysical framework and tools through which new progress could be made in science, which current scientists are dogmatic about their current metaphysics)

(particularly between 16:27-25:55 but the entire video is worth a watch)

Btw I'm not saying that they are completely correct, but rather these are interesting insights that point out some of the issues of progress in science (since they are metaphysical in nature) and plausible solutions that may be true to some degree. -

T_Clark

16.1kReification is defined as treating an idea as a concrete thing. For instance a rock is a concrete thing, you can see it, you can touch it, even smell it or taste it. You can do that with dog hair too, and with ocean water. You can't do that with a country, but you can do it with concrete things that you define as part of a country, or with a part of a concrete map that you define as a country. You can't do that with inertia, or gravity, or spacetime. That's the distinction. — leo

T_Clark

16.1kReification is defined as treating an idea as a concrete thing. For instance a rock is a concrete thing, you can see it, you can touch it, even smell it or taste it. You can do that with dog hair too, and with ocean water. You can't do that with a country, but you can do it with concrete things that you define as part of a country, or with a part of a concrete map that you define as a country. You can't do that with inertia, or gravity, or spacetime. That's the distinction. — leo

So gravity and spacetime are reifications. What about electromagnetic radiation, subatomic particles, the universe, galaxies, forests, black holes. I'll go back to oceans again. Salt water is concrete, but I don't see how an ocean is. We know space time using the same general techniques as we use to know stars - indirectly through observations of radiation which has been travelling for millions or billions are years. -

TogetherTurtle

353I think at this point of the discussion you seem to insinuate a belief that there aren't major issues with science, in that the philosophy community needs to do a better job at contributing to mankind, which philosophy hasn't been doing a good job in recent year which is why it has garnered a sort of status as a trivial discipline that is dead for the most part, which either philosophy has to be more like science in that it makes contributions that are equivalent to it (the sort contributions that science makes) or something else (which I'm trying to guess from your perspective at this point). Is this sort of accurate to your view? If not please correct me, and I do apologize if I am inaccurately portraying/strawmanning your position. — Shushi

TogetherTurtle

353I think at this point of the discussion you seem to insinuate a belief that there aren't major issues with science, in that the philosophy community needs to do a better job at contributing to mankind, which philosophy hasn't been doing a good job in recent year which is why it has garnered a sort of status as a trivial discipline that is dead for the most part, which either philosophy has to be more like science in that it makes contributions that are equivalent to it (the sort contributions that science makes) or something else (which I'm trying to guess from your perspective at this point). Is this sort of accurate to your view? If not please correct me, and I do apologize if I am inaccurately portraying/strawmanning your position. — Shushi

I apologize if it came out this way. I meant almost the opposite. My point Is that there are major issues with science, (as well as most everything else) and the responsible thing for anyone to do (a philosopher or not) is to fix something when they can instead of dealing with it when the problem becomes larger.

I believe very much so that philosophy contributes to the world. I think that particularly philosophy helps us solve problems in systems we create but can't live without. The Theseus' Ship problem for example, of course a ship is just molecules assembled into a shape, but it isn't useful for us to think of the entire universe like that. We have to make decisions about when one thing becomes another and back up our thinking with philosophical arguments. These same man-made systems make up science itself.

If there was/is a fundamental problem with philosophy that we couldn't acknowledge, I would hope that someone somewhere would point it out before our discussions become too incompatible with reality, because that benefits everyone. We all rely on each other for this. -

thewonder

1.4k

thewonder

1.4k

As much as I actually have somewhat of a bias against the preference for "logic" within scientific reasoning, I actually don't think that scientists have much of a use for Metaphysics or that Metaphysics has much of use in general. Metaphysics asks, "What is?" Scientific reasoning is better suited to the task in most regards. The whole theory and method can be better applied to everything corporeal, which I would argue is all that anything is comprised of. Nothing exists except for atoms and the void and all.

"Science" has replaced Metaphysics. Because the reasoning is better suited to task, this is not necessarily negative.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5701695-1400942436-1768.jpeg.jpg)