-

Maureen

53I presented an argument that God may not exist, or likely does not exist since He was undefined in the absence of religion. That is, at a time when there was no religion, there was also no God to speak of, and therefore God is likely only defined by religion. Of course there is always the off chance that God has always existed, even before any religion came about, but no human would know this to be the case. At any rate, in response to my initial argument, someone else replied that humans would likely still feel a sensation, or some type of presence even if there was no religion and no so-called God, and even if these things don't and never existed as we know it.

Maureen

53I presented an argument that God may not exist, or likely does not exist since He was undefined in the absence of religion. That is, at a time when there was no religion, there was also no God to speak of, and therefore God is likely only defined by religion. Of course there is always the off chance that God has always existed, even before any religion came about, but no human would know this to be the case. At any rate, in response to my initial argument, someone else replied that humans would likely still feel a sensation, or some type of presence even if there was no religion and no so-called God, and even if these things don't and never existed as we know it.

So with that said, I believe that this offers no doubt that the first humans ever to form any religion were feeling the God-like "sensation" that it is said to encompass humans even in the absence of any religion or anything like it. Moreover, these very first humans clearly used the concept of a "God" to explain this "sensation" that they were feeling without even knowing that this sensation is apparently a natural human experience, and things took off from there. What this means, therefore, is that there is effectively no "God", except as an idea that accompanies a sensation or a feeling of a presence which all humans would experience anyway. This "sensation" in effect was only given something to define it (God), which therefore indicates that this is what is to account for the concept of God. Granted anything is possible, and I realize that what I have just described isn't necessarily the case, but it does seem to make the most sense of anything given all of the information and evidence that is present. -

jorndoe

4.2kI once asked a similar question, except more "symmetrical" if you will:

jorndoe

4.2kI once asked a similar question, except more "symmetrical" if you will:

- In case one of the common religions is right (about their deity), then what would it take to think otherwise?

- Conversely, in case they're wrong and there aren't such deities, then what would it take to believe otherwise?

What does it take to be wrong about deities? -

Janus

17.9kIf you grant that God really existed after religion, then by definition God really existed before religion. If God did not really exist (as opposed to being merely imagined to exist) after religion, then he obviously did not really exist before religion either. So the advent of religion would seem to have no bearing whatsoever on the question of whether God really exists or not.

Janus

17.9kIf you grant that God really existed after religion, then by definition God really existed before religion. If God did not really exist (as opposed to being merely imagined to exist) after religion, then he obviously did not really exist before religion either. So the advent of religion would seem to have no bearing whatsoever on the question of whether God really exists or not. -

Maureen

53I once asked a similar question, except more "symmetrical" if you will:

Maureen

53I once asked a similar question, except more "symmetrical" if you will:

In case one of the common religions is right (about their deity), then what would it take to think otherwise?

Conversely, in case they're wrong and there aren't such deities, then what would it take to believe otherwise?

I feel like the answer to this is already made apparent by the fact that any one person has their own set of beliefs, and likely still will unless they can be proven wrong. So in the event that the Christian deity actually does exist but we don't know it, those who do not currently believe that deity exists would more than likely require physical proof of His existence in order to develop a belief in Him, and vice versa.

My point for this post was simply to indicate what probably brought about the concept of God as we know Him, and I believe that it is true since it makes sense on so many levels. For instance, the first people to experience the natural human sensation that I described probably first used the term "God" to define this sensation, and they ultimately decided to give praise for it since they did not realize that the sensation was perfectly natural and happens to all people. This likely led to the first semblance of a religion, and others likely followed.

This is actually the very first time that I have had a concept make perfect sense to me, and I believe that the problem up until now was that I wasn't aware that people would feel any instinctive sensation or presence if there was no such thing as religion, probably because religion has pretty much always been a part of my life since I was a child. But now that I know what I know, the idea that I have described does in fact make perfect sense to me, and I also feel like it solves the question that I have been trying to answer for so long regarding whether "God" exists. You don't have to agree with what I have said here, but I feel like it is irrefutable and makes perfect sense given the premise. -

S

11.7kIt would more likely be gods, not just a single "God". But yes, at that very early stage of humanity, where we would be really dumb compared to now, we would come up with really dumb explanations compared to current explanations. Even now, lots of people still cling to really dumb explanations, even though there are much better ones. They tell themselves and others myths, like this imagined "knowledge of God" that it is said is "lost to the sands". It's all a load of baloney, but apparently it makes some people feel better. The opium of the masses.

S

11.7kIt would more likely be gods, not just a single "God". But yes, at that very early stage of humanity, where we would be really dumb compared to now, we would come up with really dumb explanations compared to current explanations. Even now, lots of people still cling to really dumb explanations, even though there are much better ones. They tell themselves and others myths, like this imagined "knowledge of God" that it is said is "lost to the sands". It's all a load of baloney, but apparently it makes some people feel better. The opium of the masses. -

iolo

226My own notion is that early hunter-gatherer peoples got the idea that a pre-enactment of a hunt would help the real one, giving rise to the concept of a magic ritual. Rituals do catch on, and when people changed over to farming, the purpose of these dances were no longer obvious. People had dressed up as animals for the ritual dance, and to make sense of what was done, they gradually turned into some sort of magic beings, the early 'gods,' who are also animals. I think they probably produced the 'god-sensation', and people like Jesus, people with sensible proposals for human development, used that sensation to move us on.

iolo

226My own notion is that early hunter-gatherer peoples got the idea that a pre-enactment of a hunt would help the real one, giving rise to the concept of a magic ritual. Rituals do catch on, and when people changed over to farming, the purpose of these dances were no longer obvious. People had dressed up as animals for the ritual dance, and to make sense of what was done, they gradually turned into some sort of magic beings, the early 'gods,' who are also animals. I think they probably produced the 'god-sensation', and people like Jesus, people with sensible proposals for human development, used that sensation to move us on. -

Harry Hindu

5.9kHumans are inherently self-centered. Without logic and reason to check our special view of ourselves we usually invest in ideas that make us special, or the purpose of creation. It is no wonder that our ancient ancestors would contrive a story where humans are specially made by some super-human(s). Once you believe the story, then you will believe that the world is filled with the signs and symbols of the super-human(s). The special powers of the super-human(s) would be the reason you feel or sense anything.

Harry Hindu

5.9kHumans are inherently self-centered. Without logic and reason to check our special view of ourselves we usually invest in ideas that make us special, or the purpose of creation. It is no wonder that our ancient ancestors would contrive a story where humans are specially made by some super-human(s). Once you believe the story, then you will believe that the world is filled with the signs and symbols of the super-human(s). The special powers of the super-human(s) would be the reason you feel or sense anything. -

Deleted User

0Except if core drive is to feel special would you make up the existence of entities more powerful than you are. And 'specially made' fits, in some ways the Abrahamic view, but I don't think it fit, indigenous, animistic, pantheistic types of beliefs very well, since these groups tended to view themselves as one amongst many created creatures of all sort of types:spirits, minor deities, animals, plants (which were considered conscious). Humans were just one amongst many special beings, and less powerful and special than some.

Deleted User

0Except if core drive is to feel special would you make up the existence of entities more powerful than you are. And 'specially made' fits, in some ways the Abrahamic view, but I don't think it fit, indigenous, animistic, pantheistic types of beliefs very well, since these groups tended to view themselves as one amongst many created creatures of all sort of types:spirits, minor deities, animals, plants (which were considered conscious). Humans were just one amongst many special beings, and less powerful and special than some. -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

How else could they explain their existence? They certainly couldnt have thought that they came about by "random" or purposeless forces. Most people can't come to accept that idea even today.Except if core drive is to feel special would you make up the existence of entities more powerful than you are. — Coben -

Deleted User

01) I am pointing out that the story is actually humbling, since it is based on the idea that they are not the center of the universe, generally, it is the deity, in those religions that are like that. 2) Your hypothesis also does not explain why so many of the original religions did not involve people being special, they were one type amongst many others, with specialness all over the place.

Deleted User

01) I am pointing out that the story is actually humbling, since it is based on the idea that they are not the center of the universe, generally, it is the deity, in those religions that are like that. 2) Your hypothesis also does not explain why so many of the original religions did not involve people being special, they were one type amongst many others, with specialness all over the place. -

Valentinus

1.6kIt is easy enough to explain experiences by a narrative of circumstances that bring them about.

Valentinus

1.6kIt is easy enough to explain experiences by a narrative of circumstances that bring them about.

Unless, of course, the explanation is troubling in itself or requires much work on the part of the listener.

Whatever is the foundation of our appearance, it is only available for discussion through a story. We weren't there then.

So I am skeptical of the notion we have advanced much further than our ancestors did. My ancestors told me to be careful about this sort of thing. But now I have my own reasons to carry a stick on walks. -

Jesse

8I think this argument makes sense and I can see where your coming from with this logic. however, I might have to disagree and question certain points in this argument. I believe that it is fully correct to claim that perhaps the first humans to feel the god sensation probably ascribed it to there being a god and not to the fact that it is a natural human experience.

Jesse

8I think this argument makes sense and I can see where your coming from with this logic. however, I might have to disagree and question certain points in this argument. I believe that it is fully correct to claim that perhaps the first humans to feel the god sensation probably ascribed it to there being a god and not to the fact that it is a natural human experience.

However i would object to the premise that “God is likely only defined by religion”. I don't think it follows from your other premises in the argument. I agree with the first premise, In a time before religion, there was no God to speak of, however I don't think it follows that God's definition is defined by religion. I think its wrong to say that because religion began to exist, then God began to exist. I think “God” and the human concept of “God” are two different things. Perhaps the human concept of a god only began to exist when religion began, but that isn't to say that God exists only within religion. God is not defined by religion and religion is not defined by God. -

3017amen

3.1kwith that said, I believe that this offers no doubt that the first humans ever to form any religion were feeling the God-like "sensation" that it is said to encompass humans even in the absence of any religion or anything like it. — Maureen

3017amen

3.1kwith that said, I believe that this offers no doubt that the first humans ever to form any religion were feeling the God-like "sensation" that it is said to encompass humans even in the absence of any religion or anything like it. — Maureen

This might speak to your concern (s)

From Religion, Values, and Peak-Experiences:

“Most people lose or forget the subjectively religious experience, and redefine Religion [1] as a set of habits, behaviors, dogmas, forms, which at the extreme becomes entirely legalistic and bureaucratic, conventional, empty, and in the truest meaning of the word, antireligious. The mystic experience, the illumination, the great awakening, along with the charismatic seer who started the whole thing, are forgotten, lost, or transformed into their opposites. Organized Religion, the churches, finally may become the major enemies of the religious experience and the religious experiencer. This is a main thesis of this book.”

He supports this by dividing people into two categories: people (peakers) who experience “peak experiences and those who don’t (non-peakers.) The peakers are the ones who were mystics, who experienced a state of being revealed the world in a nonjudgemental ecstasy and whose descriptions became the founding of religions. This peak experience is entirely internal to the person experiencing it. The non-peakers either haven’t experienced this or have repressed it. The two types of people really do not understand each other according to Maslow.

Then Maslow goes on to say that believes the dichotomy between science and religion has become too wide. He believes that a scientist needs values, values provided by religion, to be good scientists. If they do not have these values, then they are no better than the scientists working for Adolf Hitler, experimenting on other humans and those producing weapons of war. On the other hand, religions need to accept science and realize that religion is not fixed by ritual and canonical law. By becoming fixed, they deny the peak experience and in fact become antithesis of what they profess as religion. Such religion produces sheep rather than men as the religion becomes rigid and authoritarian. Maslow believes that religious questions should be scientifically examined and discovered.

A particularly interesting passage to me is, “It has sometimes seemed to me as I interviewed “nontheistic religious people” that they had more religious (or transcendent) experiences than conventionally religious people. (This is, so far, only an impression but it would obviously be a worthwhile research project.) Partly this may have been because they were more often “serious” about values, ethics, life-philosophy, because they have had to struggle away from conventional beliefs and have had to create a system of faith for themselves individually.” As I personally searched for the origins of morals, I too have had to shed conventional beliefs about morals and observe that religions seem to follow morals rather than precede them. In other words, morals tend to create religions rather than religions create morals. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kFor much of my life I found this search for "meaning" in this sense incomprehensible. I understood the quests for truth, and for goodness, for knowledge and justice, and for means of pursuing those ends. But even in the kind of empirical, hedonic, rationalist worldview that I have long since held — which many writers on the Absurd find to be the prompt for their feelings of meaninglessness (in contrast to transcendent, fideistic, religious worldviews) — I saw the obvious potential for answering those kinds of questions about reality and morality, and couldn't comprehend what more besides that anybody wanted. "Meaning", in this sense, was, to me, meaningless.

Pfhorrest

4.6kFor much of my life I found this search for "meaning" in this sense incomprehensible. I understood the quests for truth, and for goodness, for knowledge and justice, and for means of pursuing those ends. But even in the kind of empirical, hedonic, rationalist worldview that I have long since held — which many writers on the Absurd find to be the prompt for their feelings of meaninglessness (in contrast to transcendent, fideistic, religious worldviews) — I saw the obvious potential for answering those kinds of questions about reality and morality, and couldn't comprehend what more besides that anybody wanted. "Meaning", in this sense, was, to me, meaningless.

Meanwhile however, throughout my life, I had experienced now and then times of intense positive emotion, feelings of inspiration, of enlightenment and empowerment, of a kind of oneness and connection to the universe, where it seemed to me that the whole world was eminently reasonable, that it was all so perfectly understandable even with its yet-unanswered questions and it was all beautiful and acceptable even with its many flaws. I greatly enjoyed these states of mind, and I did find that they were also practically useful both in motivating me to get things done, even just mundane chores and tasks, and also in filling me with creative thoughts, novel ideas and new solutions to problems. But although I eventually learned that these were the kinds of mental states often called "mystical" or "religious" experiences, I never took them to be in any way magical or mysterious. I saw them as just a kind of emotional high, with both experiential and behavioral benefits. Friends who had experience with drugs like LSD would even describe my recounting of such experiences as sounding like a "really good trip", further enforcing my view that these were just biochemical states of my brain (even while some of those friends conversely took their own LSD trips and such to be of genuinely mystical significance). While in such states, some things would sometimes seem "meaningful", in the sense of "important", even when I could see no rational reason why, and I always just dismissed this as a pleasantly bizarre mental artifact of the emotional high I was on. It never occurred to me to connect that sense of abstract emotional "meaning" with the thing that writers on the Absurd were seeking.

It wasn't until decades into my adult life that I first experienced clearly identifiable existential angst like had prompted the many writers on the Absurd for so long. I had long suffered with depression and anxiety, but always fixated on mundane problems in my life (though in retrospect I wonder if it wasn't those problems prompting the feelings but rather the feelings finding those problems to dwell on), and I had already philosophized a way to tackle such mundane problems despite that emotional overwhelm, which will be detailed by the end of this essay. But after many years of working extremely hard to get my life to a point where such practical problems weren't constantly besieging me, I found myself suddenly beset with what at first I thought was a physical illness, noticing first problems with my digestion, side-effects from that on my sinuses, then numbness in my face and limbs, lightheadedness, cold sweats, rapid heartbeat and breathing, and eventually total sleeplessness. Thinking I was dying of something, I saw a doctor, who told me that those are all symptoms of anxiety, nothing more. But it was an anxiety unlike any I had ever suffered before, and I had nothing going on in my life to feel anxious about now. Because of that, at first I dismissed the anxiety diagnosis and tried to physically alleviate my symptoms various ways, but as it wore on for many months, I found things to feel anxious about, facts about the universe I had already known for decades (many of which I detail later in this essay) but never emotionally worried about, which I found suddenly filling me with an existential horror or dread, a sense that any sentient being ever existing at all was like condemning it to being born already in freefall into a great cosmic meat grinder, and that reality could not possibly have been any different. Mortified, I searched in desperation for some kind of philosophical solution to that problem, something to think about that would make me stop feeling that, even trying unsuccessfully to abandon my philosophical principles and turn to religion just for the emotional relief, growing much more sympathetic to the many people who turn to religions for such relief, even as I continued to see the claims thereof as false and many of their practices as bad.

As a year of that wore on, brief moments of respite from that existential angst, dread, or horror grew mercifully longer and more frequent, often being prompted by a smaller more practical problem in my life springing up and then being resolved, distracting me from these intractable cosmic problems, at least for a time. In those moments of respite, I would often feel like I had figured out a philosophical solution to the problem: I saw my patterns of thinking while experiencing that dread as having been flawed, and the patterns of thinking I now had in this clearer state of mind as more correct. But when the dread returned, I felt like I could not remember what it was that I had thought of to solve the problem, and any attempt to get out of that state of mind simply to not feel like that any more felt like hiding from an important problem that I ought to keep dwelling on until I figured out a solution to it, even though it seemed equally clear that no solution to it was even theoretically possible. It wasn't until nearly a year of this vacillating between normalcy and existential dread had passed that the insight finally stuck me: the existential dread was just the opposite of the kind of "mysterical experiences" I had occasionally had and attached no rational significance too for my entire life. Just as, during those experiences, some things sometimes seemed non-rationally meaningful, just an ordinary experience of some scene of ordinary life with a profound feeling of "this is meaningful" attached to it, so too this feeling of existential dread was just my experience of ordinary life with a non-rational feeling of profound meaninglessness attached to it. The problem that I found myself futilely struggling to solve, I realized, was entirely illusory, and it was not irrational cowardice to hide from the "problem", but rather entirely the rational thing to do to ignore the illusory sense that there was a problem, and do whatever I could to pull my mind out of that crippling state of dread, wherein I had painfully little clarity of thought or motivational energy, and get myself back into a clearer, more productive state of mind.

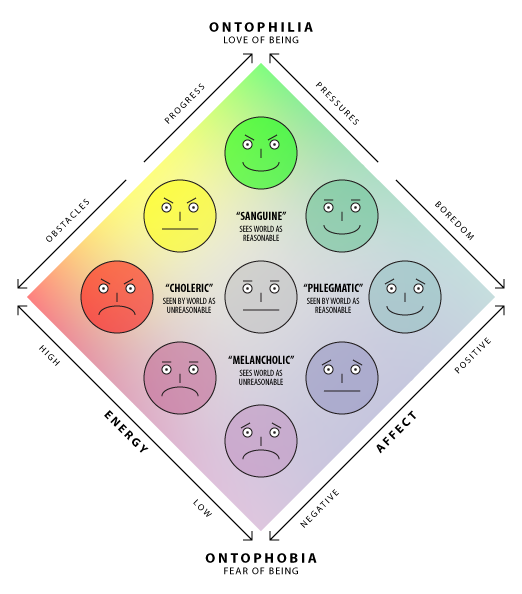

I have since dubbed that feeling of existential angst, dread, or horror "ontophobia", Greek for the fear of being, where "being" here means both the existence of the whole world generally, and of one's own personal existence; and its opposite, that experience of cosmic oneness, understanding, and acceptance, "ontophilia", Greek for the love of being, in the same sense as above. I am now of the opinion that many if not all of the writers on the Absurd, and generally anyone suffering from a feeling of meaningless in life, are not confronting a genuine philosophical problem, but merely an illusory philosophical problem stemming from a very real emotional one. Ontophobia generates the feeling of needing to find meaning in life, not the other way around. Conversely, ontophilia generates a feeling of inherent meaningfulness. Neither feeling is rationally correct or incorrect about any actual philosophical question about meaningfulness, but ontophilia is clearly the better state of mind, both for its intrinsic experiential enjoyability, but also for the practical benefits it confers of enlightening the mind and empowering the will, in the ways discussed in my previous essays on enlightenment and empowerment.

Ontophobia's illusory demand for meaning is essentially a craving for validation, for a sense that one is important and matters in some way. I realize in retrospect that so much of what I thought were mere practical concerns in my life were probably actually manifestations of this ontophobic craving for validation. My youthful longing for romance was all about feeling worthy of a partner; stress about performance at my job was all about feeling worthy as an employee; longing for an appreciative audience for my various private creative works was all about feeling worthy as an author, artist, etc. It was only once those were mostly all satisfied that the bare emotional motive behind them all truly showed itself, the true existential dread being all about craving to feel like it matters whether or not I, or anyone, even live at all.

Ontophilia, on the other hand, can produce equally illusory feelings that nevertheless seem overwhelmingly real and undeniable. Being the quintessential "mystical experience" or "religious experience", it is the supposed source of "revealed" knowledge held to be divinely inspired and infallibly true by many religions. (I am of the opinion that ontophilia is the proper referent of the term "God" as used by theological noncognitivists, who are people that use religious terminology not for describing reality per se, but more for its emotional affect. Most theological noncognitivists do not identify as such and are not aware of this philosophical technicality in their use of language, but it it evident in expressions such as "God is love", whereby "believing in God" does not seem to mean so much a claim about the ontological existence of a particular being, but an expression of good will toward the world and of an expectation that the world generally reciprocates such goodness. It seems also plausibly equatable to the Buddhist concept of "nirvana", or the ancient Greek concept of "eudaimonia", which were the "meanings of life" of those respective traditions). As such, ontophilia still needs to be tempered by more sober reflection; although I have had many seemingly great creative ideas when in such states of mind, not all of them have held up to later scrutiny, though some still have, so not all ideas produced in such states of mind should be dismissed out of hand. Actions motivating by ontophilia can also be manic in their passion and dedication, which if misguided can be dangerous, either to oneself or to others.

I compare ontophilia to mania there deliberately, and likewise I compare ontophobia to depression and of course to anxiety. I consider them to be extremes of one axis of a two-dimensional spectrum of emotions that I devised introspectively to help make sense of my own mental health. I name the four extreme moods of this spectrum after the classical Greek four temperaments, which in turn were named after the four bodily fluids or "humors" that ancient Greek physicians held to be responsible for such temperaments: phlegmatic (after phlegm of course), sanguine (after blood), choleric (after yellow bile), and melancholic (after black bile). I of course don't subscribe to the long-outdated medical theory of these four humors, but the names of the temperaments are useful labels for my purposes here. The model of four temperaments usually casts them as personality types, with an individually being generally more one or the other, but I mean them here as moods, between all of which any one individual may vacillate. I place these four moods in the corners of a two-dimensional axis of emotional energy and emotional affect. Phlegmatic moods are those of low energy and positive affect, a kind of relaxed happiness, what we might call peace. Sanguine moods are those of high energy and positive affect, a kind of excited happiness, what we might call joy. Choleric moods are those of high energy and negative affect, essentially intense anger. And melancholic moods are those of low energy and negative affect, essentially intense sorrow.

I observe in myself that pressure to act increases my energy, while boredom decreases it; and progress in my actions makes my affect more positive, while obstacles make it more negative. I hold that ontophilia is simply an extremely sanguine, high-energy, positive-affect mood, while ontophobia is likewise an extremely melancholic, low-energy, negative affect mood. And just as an ontophilic or generally sanguine mood leads to seeing the world as reasonable, understandable and acceptable, while an ontophobic or generally melancholic mood leads to seeing it as unreasonable, incomprehensible, and terrifying, I likewise observe that other people in the world generally find people in phlegmatic moods to seem reasonable, sane, and safe, while people in choleric moods seem to them unreasonable, crazy, and dangerous. It seems clearly ideal, then, to aim to cycle between ontophilic or at least generally sanguine moods, for the sake of the enlightening and empowering effects they have on the mind and will, and phlegmatic moods for the sake of a more grounded check on how actually true and good the things inspired by the ontophilia are, and to communicate them to others. (This even bears a passing resemblance to the Scholastic philosophers' view of the relation between revelation and reason: they held revelation, which I equate to ontophilic inspiration, to be sufficient to know what was true, with reason there to later investigate further why it was true. I disagree with that on the important point that I don't hold ontophilic inspiration to be infallible, and the role of reason is then to critique the inspired ideas rather than rationalizing justification for them, but I see a resemblance still). Nevertheless, ontophobic or melancholic moods, and even choleric moods, are not entirely without their uses: anger can of course be a useful motivator if properly channelled, and in the depths of the existential dread affecting me I found myself more moved toward compassionate action, both so as not to further contribute to the horrors of reality I perceived all around me, and also as an emotional salve to try to alleviate my own emotional suffering from the same.

On which note, I find that, aside from simply allowing myself to ignore the meaningless craving for meaning that ontophobia brings on, the way to cultivate ontophilia is to practice the very same behaviors that it in turn inspires more of. Doing good things, either for others or just for oneself, and learning or teaching new truths, both seem to generate feelings of empowerment and enlightenment, respectively, and as those ramp up in a positive feedback loop, inspiring further such practices, an ontophilic state of mind can be cultivated. In addition to that practice, I find that it helps to remain at peace and alleviate feelings of anxiety and unworthiness by not only doing all the positive things that I reasonable can do, as above, but also excusing or forgiving myself from blame for not doing things that I reasonably can't do. It is of course very hard to do this sometimes, so it helps also to cultivate a social network of like-minded people who will gently encourage you to do the things you reasonably can, and remind you that it's okay to not do things that you reasonably can't, between the two of which you can hopefully find a restful peace of mind where you feel that you have done all that you can do and nothing more is required of you, allowing you to enjoy simply being. Furthermore, meditative practices are essentially practice at allowing oneself to do nothing and simply be, to help cultivate this state of mind; a popular prayer (that I will revisit again later in these essays) asks for precisely such serenity to accept things one cannot change and courage to change the things one can; and the modern cognitive-behavioral therapy technique called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is also entirely about committing to doing the things that one can do and accepting the things that one cannot do anything about. — The Codex Quaerendae: On Practical Action and the Meaning of Life

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- If there was no God to speak of, would people still feel a spiritual, God-like sensation?

- Does God(s) exist without religion? How is this possible spiritually?

- In what capacity did God exist before religion came about, if at all? How do we know this?

- Peter Kreeft and Ronald K. Tacelli - Twenty Arguments for the Existence of God

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum