-

jorndoe

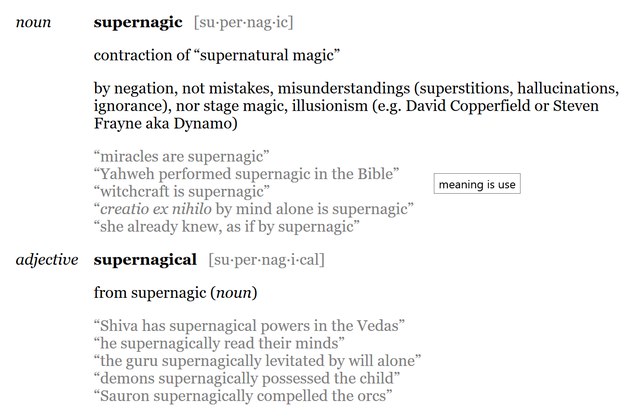

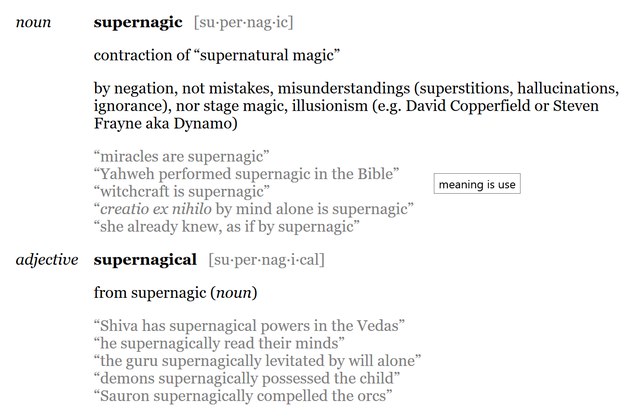

4.2kTo try moving past semantic quibbles I'll go by this definition:

jorndoe

4.2kTo try moving past semantic quibbles I'll go by this definition:

Supernatural magic (supernagic) could (literally) be raised to explain anything, and therefore explains nothing.

Might as well be replaced with "don't know", which incurs no information loss.

Is not itself explicable, cannot readily be exemplified (verified), does not derive anything in particular (or could derive anything), and has been falsified plenty in the past.

Much like an epistemic gap-filler.

A non-explanation.

(Also see Bible Genesis:1, Quran 2:117, ...)

But what do you think?-

Supernagic is ... real50%nonsense50%

-

Supernagic is ...

-

OmniscientNihilist

171supernagic) could (literally) be raised to explain anything, and therefore explains nothing. — jorndoe

OmniscientNihilist

171supernagic) could (literally) be raised to explain anything, and therefore explains nothing. — jorndoe

people may be using he supernatural answer in two different ways:

saying 'i dont know' is different then saying 'i cannot know'

saying 'i dont know' = simply confessing ignorance

saying 'i cannot know' = making a claim that the answer is intrinsically unknowable

using supernatural as an explanation could simply be a temporary gap filler until science answers the question or it would be a statement of fact that the answer is and always will be supernatural(beyond physical science)

hard problem of consciousness for example, is pointing out both. its pointing out that we:

1-currently do not know

2-may never know

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hard_problem_of_consciousness -

jorndoe

4.2kAnother gap, ?

jorndoe

4.2kAnother gap, ?

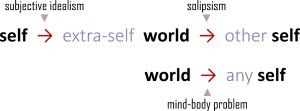

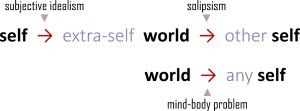

Levine's explanatory gap / Chalmers' consciousness conundrum is a can of worms.

That being said, we do know things, though, both about mind and the world; appeal to supernagic seems a bit ... odd.

We might also be able to account coherently for that gap before trying to bridge it (self-identity, individuation, ...).

-

OmniscientNihilist

171appeal to supernagic seems a bit ... odd. — jorndoe

OmniscientNihilist

171appeal to supernagic seems a bit ... odd. — jorndoe

it's more knowledgeable to be aware of your ignorance then to not be

and its more humble to admit your ignorance then not to

hard problem of consciousness is doing both

meanwhile materialism is just ignorant of the problem and too arrogant to admit it -

jorndoe

4.2kaware of your ignorance — OmniscientNihilist

jorndoe

4.2kaware of your ignorance — OmniscientNihilist

Let's not pretend to know what we don't. :up:

don't know — Opening post -

OmniscientNihilist

171Let's not pretend to know what we don't. — jorndoe

OmniscientNihilist

171Let's not pretend to know what we don't. — jorndoe

good.

lets not pretend we know that the brain creates consciousness

and lets not pretend we know consciousness is even in the brain

and lets not pretend we know consciousness does not survive the death of the brain

and lets not pretend we know the brain even exists when your not looking at it

and all the other assumptions of materialist philosophy peddled as science -

jorndoe

4.2k, I guess, for the purpose here, real can be contrasted by fictional.

jorndoe

4.2k, I guess, for the purpose here, real can be contrasted by fictional.

So, your Harry Potter model is real, and Harry Potter is not. -

Echarmion

2.7k

Echarmion

2.7k

When we say "fictional", we usually mean that something is not physically real, and the method to tell what's physically real is the scientific method. E.g. there is no evidence of a physical Harry Potter living in physical England, and hence we conclude Harry Potter doesn't exist. But "supernatural" means the same as "non-physical", so the answer to your question would have to be "no" by definition. -

Deleted User

0Do words not physically exist? Can we not say Harry Potter physically exists as a word in a book which is attached to our idea of Harry Potter?

Deleted User

0Do words not physically exist? Can we not say Harry Potter physically exists as a word in a book which is attached to our idea of Harry Potter? -

TheMadFool

13.8kI think I "understand".

Supernagic = supernatural + magic.

The supernatural, by itself, can be invoked anytime a known law of nature is violated with religious undertones of course.

Magic requires a magician - a purposeful intender if you will.

Thus supernagic is when there exists (a) person(s) who is/are intentionally or unwittingly performing supernatural acts.

It could be God or his messenger/prophet ( :rofl: ) or Descartes' demon. I sincerely hope it's not the latter. To think of it even the former possibility is laden with difficulties. -

Deleted User

0

Deleted User

0

I think some of what gets classed as supernatural magic is real. I said 'classed as' since I think these phenomena are simply things that science has not (yet) or perhaps cannot confirm or won't in the near future, but they are real phenomena. One could say I consider them natural, in the sense that they are part of the potential processes of reality. Not things that are 'super' to reality. They are not breaking rules, they follow rules or laws or potentials. I have experienced enough of some of these pheneomena to be convinced.But what do you think? — jorndoe -

Echarmion

2.7kDo words not physically exist? Can we not say Harry Potter physically exists as a word in a book which is attached to our idea of Harry Potter? — Mark Dennis

Echarmion

2.7kDo words not physically exist? Can we not say Harry Potter physically exists as a word in a book which is attached to our idea of Harry Potter? — Mark Dennis

That might get us down a rabbit hole concerning where the meaning of words resides. But yes, the Harry Potter books are physically real.

There's also a sense in which Harry Potter is a real character in the books, as opposed to, say, fan fiction. -

Deleted User

0Well I think we need to have that sense else we wouldn’t be able to discuss fiction properly. Outside of books, saying “Harry Potter is a wizard” and saying “Harry Potter is a space Marine” are both equally untrue. However when we enter into fiction, what we are doing is entering into that universe of discourse; thereby making a contract with each other to converse as if the universe of discourse exists so we can make true statements about it.

Deleted User

0Well I think we need to have that sense else we wouldn’t be able to discuss fiction properly. Outside of books, saying “Harry Potter is a wizard” and saying “Harry Potter is a space Marine” are both equally untrue. However when we enter into fiction, what we are doing is entering into that universe of discourse; thereby making a contract with each other to converse as if the universe of discourse exists so we can make true statements about it.

I forget who’s work I’m basing this off; but I believe one of the terms they came up with to describe and differentiate existence with fiction and abstract ideas. I believe the term was subsistence. I exist, Harry Potter Subsists. We can also say God subsists as God has the same amount of influence on existence as Harry Potter does. Well not the same amount but they both share the quality of subsistence as opposed to existence.

With this in mind; Is it possible to get outside of the Human universe of discourse for us? -

Deleted User

0@Echarmion

Deleted User

0@Echarmion

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/possible-objects/#SubVsExi3.1 Subsistence vs. Existence

Alexius Meinong’s theory of objects has had much influence on some contemporary theorists, resulting in a variety of proposals. These proposals are known broadly as Meinongian. According to Meinong, a subject term in any true sentence stands for an object (Meinong 1904). So the subject term in the sentence, ‘The sixth right finger of Julius Caesar is a finger’, stands for an object, assuming that the sentence is true. (Such an assumption is strongly disputed in Salmon 1987.) Even though the exact respects in which contemporary Meinongian proposals are Meinongian and the extent of their Meinongianism differ from one proposal to another, all of them inherit this claim by Meinong in some form. They are thus united in resisting Bertrand Russell’s criticism of Meinong, which mandates analyzing sentences containing a definite description, like the one above concerning the sixth right finger of Julius Caesar, as general statements rather than singular statements (Russell 1905); see 3.1.2 for a particularly famous piece of Russell’s criticism and how two leading Meinongian theories handle it.

Meinong distinguishes two ontological notions: subsistence and existence. Subsistence is a broad ontological category, encompassing both concrete objects and abstract objects. Concrete objects are said to exist and subsist. Abstract objects are said not to exist but to subsist. The talk of abstract objects may be vaguely reminiscent of actualist representationism, which employs representations, which are actual abstract objects. At the same time, for Meinong, the nature of an object does not depend on its being actual. This seems to give objects reality that is independent of actuality. Another interesting feature of Meinong’s theory is that it sanctions the postulation not only of non-actual possible objects but also of impossible objects, for it says that ‘The round square is round’ is a true sentence and therefore its subject term stands for an object. This aspect of Meinong’s theory has been widely pointed out, but non-trivial treatment of impossibility is not confined to Meinongianism (Lycan & Shapiro 1986). For more on Meinong’s theory, see Chisholm 1960, Findlay 1963, Grossmann 1974, Lambert 1983, Zalta 1988: sec.8. For some pioneering work in contemporary Meinongianism, see Castañeda 1974, Rapaport 1978, Routley 1980. We shall examine the theories of two leading Meinongians: Terence Parsons and Edward Zalta. We shall take note of some other Meinongians later in the section on fictional objects, as their focus is primarily on fiction. Parsons and Zalta not only propose accounts of fictional objects but offer comprehensive Meinongian theories of objects in general.

Here it is! It was Meinongianism I was thinking of. -

Deleted User

0Sticking more to the OP; in the sentence “Witchcraft is a type of supernagic” to me is describing not something of supernatural origin. It’s describing a large divide in practical knowledge between the perceived Witch and the perceived non witches.

Deleted User

0Sticking more to the OP; in the sentence “Witchcraft is a type of supernagic” to me is describing not something of supernatural origin. It’s describing a large divide in practical knowledge between the perceived Witch and the perceived non witches.

Supernagic to me is just a way of identifying a huge chasm of ignorance between the entity being described thusly, and the entities doing the describing.

Give me a time Machine, a cigarette lighter, a pressurised can of flammable liquid, a gun and a hoard of modern Anti biotics and I have the power to be perceived as a god in much of the past so long as I keep everyone in the past ignorant of how I am performing these “Miracles”. -

Harry Hindu

5.9kSupernagic is ...

Harry Hindu

5.9kSupernagic is ...

real or nonsense — jorndoe

Supernagic is a real word (it's there on the screen) that refers to a nonsense idea.

What does it mean to be unknowable? Is it that it is knowable to some, but not to others? Or is it that there is nothing to know at all - that we are mistaking imaginary things for real things and then asking questions about those imaginary things as if they were real.saying 'i cannot know' = making a claim that the answer is intrinsically unknowable — OmniscientNihilist -

jorndoe

4.2kGive me a time Machine, a cigarette lighter, a pressurised can of flammable liquid, a gun and a hoard of modern Anti biotics and I have the power to be perceived as a god in much of the past so long as I keep everyone in the past ignorant of how I am performing these “Miracles”. — Mark Dennis

jorndoe

4.2kGive me a time Machine, a cigarette lighter, a pressurised can of flammable liquid, a gun and a hoard of modern Anti biotics and I have the power to be perceived as a god in much of the past so long as I keep everyone in the past ignorant of how I am performing these “Miracles”. — Mark Dennis

Right. This would be ignorance.

Clarke's three laws:

3. Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. -

jorndoe

4.2k[...] It could be God or his messenger/prophet ( :rofl: ) or Descartes' demon. I sincerely hope it's not the latter. To think of it even the former possibility is laden with difficulties. — TheMadFool

jorndoe

4.2k[...] It could be God or his messenger/prophet ( :rofl: ) or Descartes' demon. I sincerely hope it's not the latter. To think of it even the former possibility is laden with difficulties. — TheMadFool

Doesn't this stuff fall under "don't know"? -

jorndoe

4.2kIt was Meinongianism I was thinking of. — Mark Dennis

jorndoe

4.2kIt was Meinongianism I was thinking of. — Mark Dennis

This could turn into a long side-avenue all by itself. :)

@Ying might have some insights on Meinong's jungle. -

Deleted User

0might have some insights on Meinong's jungle. — jorndoe

Deleted User

0might have some insights on Meinong's jungle. — jorndoe

And in the heart of Meinong’s Jungle, lies the little village of Southpark Colorado haha -

Wayfarer

26.1kSo (per Feynman), magic = don't know ? — jorndoe

Wayfarer

26.1kSo (per Feynman), magic = don't know ? — jorndoe

There’s more to it than ‘don’t know’, isn’t there? Quantum mechanics works, it provides the principles underlying much of current science and technology. But it has undertones of voodoo, of spookiness (i.e. ‘spooky action at a distance’) and also magic. -

OmniscientNihilist

171What does it mean to be unknowable? — Harry Hindu

OmniscientNihilist

171What does it mean to be unknowable? — Harry Hindu

it simply means you know that you cannot know. because there is something blocking your limited ability to know.

thing can be temporarily unknowable or permanently unknowable

and you can potential know that

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum