-

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kUnderstanding a complex logical argument results from the associating of its parts, The parts consist of immediately apprehended insights and the associations between them are also direct insights. What else could the associations be but further direct insights ? They cannot be composed of mechanically following rules without any insight, because then you would need further rules to tell you how to follow the rules, creating an infinitely regressive and complex proliferation of rules which would make any understanding or following of logical arguments impossible. — John

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kUnderstanding a complex logical argument results from the associating of its parts, The parts consist of immediately apprehended insights and the associations between them are also direct insights. What else could the associations be but further direct insights ? They cannot be composed of mechanically following rules without any insight, because then you would need further rules to tell you how to follow the rules, creating an infinitely regressive and complex proliferation of rules which would make any understanding or following of logical arguments impossible. — John

So you've rendered all forms of thought as intuitive. There is no distinction for you between things known intuitively and things known by reason?

Whether you draw the general form of the maple leaf or merely imagine it, it cannot be the exact form of any particular maple leaf. It is a kind of 'averaged' form. — John

When you draw a maple leaf, it is a particular form which you have drawn. It is not the general form of the maple leaf.

It appears like you do not distinguish between a particular and a universal. We would need to come to some agreement on this before we could produce any progress in this discussion.I am not going to attempt too address any of the rest of your long post. I think these are the salient points, anyway, and discussion will be much more manageable if we just deal with them. — John

Any particular instance of a maple leaf, whether it is drawn, or growing on a tree, is a particular. On the other hand, there is a class of things which we call maple leaves. "Maple leaf" is the title of that class. So there is a universal which is called "maple leaf". Any individual person has rules or principles which one follows, guiding one to class a particular thing as a maple leaf. When we refer to "the general form" of the maple leaf, we refer to these guiding principles by which we distinguish the class "maple leaf", and we judge particulars as maple leafs. The general form, cannot be any particular instance of a maple leaf, it is the defining features of the class. That is why it is understood that a general form exists by definition. You can see this clearly in geometry, things like "triangle", "square", "right angle", "circle", are all general forms which exist by definition. -

Janus

17.9kSo you've rendered all forms of thought as intuitive. There is no distinction for you between things known intuitively and things known by reason? — Metaphysician Undercover

Janus

17.9kSo you've rendered all forms of thought as intuitive. There is no distinction for you between things known intuitively and things known by reason? — Metaphysician Undercover

Things are known intuitively by means of the senses, or intuitively by means of thought, no? A rational argument could never convince if you didn't 'get' it, right? 'Getting it' is intuitive.

When you draw a maple leaf, it is a particular form which you have drawn. It is not the general form of the maple leaf. — Metaphysician Undercover

Sure every drawing of a maple leaf is a particular form, just as every drawing of an equilateral triangle is really a particular form. But the drawings are particular only in terms of their inevitable imperfections.

Any individual person has rules or principles which one follows, guiding one to class a particular thing as a maple leaf. — Metaphysician Undercover

Yes, one intuitively grasps the general form of the maple leaf, and if one draws it looks something like this:

This is a visual representation of the generalized form of the maple leaf. It is not an image of any particular maple leaf. Probably no maple leaf in existence is so perfectly symmetrical, or has perfectly straight edges. -

Wayfarer

26.1kSure every drawing of a maple leaf is a particular form, just as every drawing of an equilateral triangle is really a particular form. But the drawings are particular only in terms of their inevitable imperfections. — John

Wayfarer

26.1kSure every drawing of a maple leaf is a particular form, just as every drawing of an equilateral triangle is really a particular form. But the drawings are particular only in terms of their inevitable imperfections. — John

We abstract that particular form, and this constitutes our representation of object MLt3 — Metaphysician Undercover

Ed Feser, who describes himself as 'Aristotelean-Thomist', presents the idea that 'the concept of triangle' is neither a visual representation or a particular idea, but a concept.

Consider the most unambiguous symbol of triangularity there could be—a picture of a triangle, such as the one to the right. Now, does this picture represent triangles in general? Or only isosceles triangles? Or only small isosceles triangles drawn in black ink? Or does it really even represent triangles in the first place? Why not take it instead to represent a dinner bell, or an arrowhead? There is nothing in the picture itself that can possibly tell you. Nor would any other picture be any better. Any picture would be susceptible of various interpretations, and so too would anything you might add to the picture in order to explain what the original picture was supposed to represent. In particular, there is nothing in the picture in question or in any other picture that entails any determinate, unambiguous content.

- See more at: http://biologos.org/blogs/archive/rediscovering-human-beings-part-1#sthash.YuCejRSh.dpuf

Consider that when you think about triangularity, as you might when proving a geometrical theorem, it is necessarily perfect triangularity that you are contemplating, not some mere approximation of it. Triangularity as your intellect grasps it is entirely determinate or exact; for example, what you grasp is the notion of a closed plane figure with three perfectly straight sides, rather than that of something which may or may not have straight sides or which may or may not be closed. Of course, your mental image of a triangle might not be exact, but rather indeterminate and fuzzy. But to grasp something with the intellect is not the same as to form a mental image of it. For any mental image of a triangle is necessarily going to be of an isosceles triangle specifically, or of a scalene one, or an equilateral one; but the concept of triangularity that your intellect grasps applies to all triangles alike. Any mental image of a triangle is going to have certain features, such as a particular color, that are no part of the concept of triangularity in general. A mental image is something private and subjective, while the concept of triangularity is objective and grasped by many minds at once.

Feser, Some Brief Arguments for Dualism -

Janus

17.9kBut to grasp something with the intellect is not the same as to form a mental image of it.

Janus

17.9kBut to grasp something with the intellect is not the same as to form a mental image of it.

I'd say that when it comes to visual forms at least, to grasp something just is to form a visual image of it. So, I guess I disagree with Feser.

Also his point that purported representations of triangles could be thought to be representations of arrowheads or whatever seems irrelevant irrelevant since if a representation of a triangle was thought to be a representation of an arrowhead, then arrowheads would be being thought of as triangular. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI'd say that when it comes to visual forms at least, to grasp something just is to form a visual image of it. So, I guess I disagree with Feser. — John

Wayfarer

26.1kI'd say that when it comes to visual forms at least, to grasp something just is to form a visual image of it. So, I guess I disagree with Feser. — John

Well, Feser has answers for that:

mental images are always to some extent vague or indeterminate, while concepts are at least often precise and determinate. To use Descartes’ famous example, a mental image of a chiliagon (a 1,000-sided figure) cannot be clearly distinguished from a mental image of a 1,002-sided figure, or even from a mental image of a circle. But the concept of a chiliagon is clearly distinct from the concept of a 1,002-sided figure or the concept of a circle. I cannot clearly differentiate a mental image of a crowd of one million people from a mental image of a crowd of 900,000 people. But the intellect easily understands the difference between the concept of a crowd of one million people and the concept of a crowd of 900,000 people. And so on. -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

I don't believe we can visualize extremely complex objects except to kind of mentally traverse the charateristic features we are familiar with that make them the uniqely particular objects they are.

So I wouldn't agree with Feser that we can have a mental image of a chiliagon at all, other than kind of vaguely imagining what it might look like by analogy with something we can visualize like a hexagon or octagon.

I am basing what I say on my own experience, on what I find I can and cannot visualize. Others may well be able to do things I cannot. -

Punshhh

3.6kPerhaps this is like try to getting your head around infinity. You just end up imagining a very large quantity or size, then you intellectually multiply it in some way to make it seem larger. But then there is a kind of leap from there to some kind of acceptance of a mathematical axiom. The imagined infinity is never realised. A grasping of an infinity always fails, or a mental representation of infinity always fails and the mind has to side track into a belief about mathematical principles and take it on faith from the math that there is such a thing as infinity. Then the mind goes back to where it tried to mentally represent the infinity in the first place and kind of puts a belief there instead of a mental representation. But then pretends that an infinity has been grasped, understood, a kind of conciet.

Punshhh

3.6kPerhaps this is like try to getting your head around infinity. You just end up imagining a very large quantity or size, then you intellectually multiply it in some way to make it seem larger. But then there is a kind of leap from there to some kind of acceptance of a mathematical axiom. The imagined infinity is never realised. A grasping of an infinity always fails, or a mental representation of infinity always fails and the mind has to side track into a belief about mathematical principles and take it on faith from the math that there is such a thing as infinity. Then the mind goes back to where it tried to mentally represent the infinity in the first place and kind of puts a belief there instead of a mental representation. But then pretends that an infinity has been grasped, understood, a kind of conciet. -

dukkha

206The best argument against subjective idealism is "account for intersubjectivity."

dukkha

206The best argument against subjective idealism is "account for intersubjectivity."

If esse est percipi, then others are exhausted by your perception of them.

Because others aren't exhausted by my perception of them (proof: it is undeniable you are reading this), subjective idealism is false. -

Wayfarer

26.1kEsse est percipe is a phrase that is inexorably connected with Berkeley, who is also the poster boy for subjective idealism. Nothing 'confusing' about that.

Wayfarer

26.1kEsse est percipe is a phrase that is inexorably connected with Berkeley, who is also the poster boy for subjective idealism. Nothing 'confusing' about that.

In any case, the OP is an example of many of the kinds of objections that Berkeley's imagined opponents came up with in his dialogues. He didn't address the 'drugged water pitcher' scenario but I have no doubt, if Hylas had presented it, Philonous would have come up with a convincing rebuttal. -

Terrapin Station

13.8kthe most powerful nation has just elected a liar and charlatan as leader of the free world — Wayfarer

Terrapin Station

13.8kthe most powerful nation has just elected a liar and charlatan as leader of the free world — Wayfarer

"Liar" is a another word for "politician," isn't it? We always elect liars, and we must always, since running for and/or holding office makes one a politician.

Of course I'm being a bit facetious there, but there are serious points in my flippancy, too. I believe that everyone is a liar in some respects, and I believe that it's impossible for anyone to have a viable chance of becoming president of a country like the U.S. without making promises one won't keep for various reasons, without being corrupt in some respects, etc. -

Michael

16.8kIf esse est percipi, then others are exhausted by your perception of them. — dukkha

Michael

16.8kIf esse est percipi, then others are exhausted by your perception of them. — dukkha

I don't know why this fallacy keeps repeating itself. There's a difference between "to be is to be perceived" and "to be is to be perceived by me". You can't go from the former to "others are exhausted by my perception of them".

It's like going from "to be a wife is to be a married woman" to "so-and-so is a wife only if she's married to me". -

Terrapin Station

13.8kI don't know why this fallacy keeps repeating itself. — Michael

Terrapin Station

13.8kI don't know why this fallacy keeps repeating itself. — Michael

It stems either from someone saying they can only know their own mental content or from not explaining how only mental phenomena exist yet nevertheless one can know and or experience other mentalities. -

Michael

16.8kIt stems either from someone saying they can only know their own mental content — Terrapin Station

Michael

16.8kIt stems either from someone saying they can only know their own mental content — Terrapin Station

Then it's a matter of epistemology, not ontology. So I might not know that other minds exist, but it is nonetheless the case that to be is to be perceived and that there are (or may be) other minds. It's no different to the materialist who might say that there are (or may be) unknown material things.

or from not explaining how only mental phenomena exist yet nevertheless one can know and or experience other mentalities.

I don't understand the problem. -

Terrapin Station

13.8kThen it's a matter of epistemology, not ontology. — Michael

Terrapin Station

13.8kThen it's a matter of epistemology, not ontology. — Michael

The idea is that what you're considering a fallacy is stemming from a view that the idealist in question's epistemology can't support the ontological claims they're making.

Realists often do not believe that they can't know externals. For example, I do not believe that.

The other problem is simply that that view seems to always be left unexplained in terms of how it would work. -

dukkha

206In any case, the OP is an example of many of the kinds of objections that Berkeley's imagined opponents came up with in his dialogues. He didn't address the 'drugged water pitcher' scenario — Wayfarer

dukkha

206In any case, the OP is an example of many of the kinds of objections that Berkeley's imagined opponents came up with in his dialogues. He didn't address the 'drugged water pitcher' scenario — Wayfarer

I believe OP is arguing against a subjective idealism where the only minds that exist are human minds (and possibly, some animals). Whereas the drugged water for Berkeley's idealism continues to be 'held' in existence by the mind of god. His whole argument makes no sense if he's arguing against Berkeley. -

dukkha

206I don't know why this fallacy keeps repeating itself. There's a difference between "to be is to be perceived" and "to be is to be perceived by me". You can't go from the former to "others are exhausted by my perception of them". — Michael

dukkha

206I don't know why this fallacy keeps repeating itself. There's a difference between "to be is to be perceived" and "to be is to be perceived by me". You can't go from the former to "others are exhausted by my perception of them". — Michael

Yeah but the default position is realism, and one generally comes to idealsim through epistemic concerns about realism. And so it only seems logical that the epistemic concern will follow a natural progression from external world -> ideal world -> my ideal world. Otherwise you don't have epistemic concerns in general, you just have epistemic concerns about the material world.

I mean sure, a subjective idealist can just dogmatically assert the existence of other minds, even though he does not perceive them himself. But it's kind of non-nonsensical to do this, along with bad philosophy. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k, do you recognize that the drawing of the maple leaf you have presented to me is a particular? You have presented it to me as a representation of the general form of the maple leaf. Therefore it is not the general form of the maple leaf, it is a particular which is intended as a representation of the general form. So if we are talking about the true "general form" of the maple leaf we are talking about something other than such a particular representation.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k, do you recognize that the drawing of the maple leaf you have presented to me is a particular? You have presented it to me as a representation of the general form of the maple leaf. Therefore it is not the general form of the maple leaf, it is a particular which is intended as a representation of the general form. So if we are talking about the true "general form" of the maple leaf we are talking about something other than such a particular representation.

The difficult factor to understand is that each representation such as that, is a particular. The general form is a universal, and therefore cannot be any particular. So it does not matter how many times you try to represent the general form as a particular, what you present to me will always be particular representation, and not the general form.

I don't believe we can visualize extremely complex objects except to kind of mentally traverse the charateristic features we are familiar with that make them the uniqely particular objects they are.

So I wouldn't agree with Feser that we can have a mental image of a chiliagon at all, other than kind of vaguely imagining what it might look like by analogy with something we can visualize like a hexagon or octagon.

I am basing what I say on my own experience, on what I find I can and cannot visualize. Others may well be able to do things I cannot. — John

Do you agree that you can understand the meaning of "chiliagon", as a 1000 sided figure, without having to visualize it? You can understand it by placing it into relationships with other things. You know that it is a 1000 sided figure, that it is different from a 1002 sided figure, and that it is different from circle. Simply by the means of such descriptions, you can understand it. This is how we understand the principles of mathematics, not by picturing 2 items 20 items, 200, or 2000 items, we understand through described relationships, order. The symbols are assigned an order, and the order is understood and maintained. You can understand what a trillion is, not because you can picture it, but because you know that it has a position in a very specific order, and you know that it cannot be otherwise from this very specific position. That order is not represented spatially.

I'm sure you are aware that in modern physics there is a large number of sub-atomic particles. The existence of the particles are understood with mathematics. When speaking to physicists, they will often caution you, not to try to visualize the things which they are telling you about. The words used, such as "particle", tend to bring up certain images, but you are told by the physicists not to refer to these images. The concepts are purely mathematical, and the words in the context of particle physics, refer to these mathematical concepts, rather than any image you can make in your mind. So they have "particles", and the particles have "spin", but these concepts are purely mathematical, and not something you can imagine. The fact that no one cannot imagine these concepts does not indicate that the physicists do not know what the words mean.

By maintaining faith in the numerical order we can come to understand all kinds of wonderful things which we cannot possibly imagine. You may be inclined to question that faith, but it's really not much different from the trust you give to your ability to imagine. You pass me a drawing of a maple leaf, and I trust you, that this is really what a maple leaf looks like. Now I know what a maple leaf looks like, but that knowledge depends on the veracity of that trust. In a similar way, if I multiply 465 X 43, I now know that this makes 19,995. But even after I confirm my ability to multiply, I only know this through my faith in the numerical order. The numerical order is not represented spatially, and this is why mathematical understanding is based in faith rather than visual representation. -

Marchesk

4.6kI believe OP is arguing against a subjective idealism where the only minds that exist are human minds (and possibly, some animals). Whereas the drugged water for Berkeley's idealism continues to be 'held' in existence by the mind of god. His whole argument makes no sense if he's arguing against Berkeley. — dukkha

Marchesk

4.6kI believe OP is arguing against a subjective idealism where the only minds that exist are human minds (and possibly, some animals). Whereas the drugged water for Berkeley's idealism continues to be 'held' in existence by the mind of god. His whole argument makes no sense if he's arguing against Berkeley. — dukkha

That's correct, which is why I mentioned subjective idealism. -

tom

1.5kI'm sure you are aware that in modern physics there is a large number of sub-atomic particles. The existence of the particles are understood with mathematics. When speaking to physicists, they will often caution you, not to try to visualize the things which they are telling you about. The words used, such as "particle", tend to bring up certain images, but you are told by the physicists not to refer to these images. The concepts are purely mathematical, and the words in the context of particle physics, refer to these mathematical concepts, rather than any image you can make in your mind. — Metaphysician Undercover

tom

1.5kI'm sure you are aware that in modern physics there is a large number of sub-atomic particles. The existence of the particles are understood with mathematics. When speaking to physicists, they will often caution you, not to try to visualize the things which they are telling you about. The words used, such as "particle", tend to bring up certain images, but you are told by the physicists not to refer to these images. The concepts are purely mathematical, and the words in the context of particle physics, refer to these mathematical concepts, rather than any image you can make in your mind. — Metaphysician Undercover

Physicists spend a great deal of time and computing power creating images of what they are studying, including new fundamental particles:

-

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kPhysicists spend a great deal of time and computing power creating images of what they are studying, including new fundamental particles: — tom

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kPhysicists spend a great deal of time and computing power creating images of what they are studying, including new fundamental particles: — tom

The problem is, that these images don't adequately represent concepts which cannot be represented by images, so all they're doing is making an appeal to the sensibilities of common people who enjoy such phantasms. That they spend a great deal of time and computing power on this is an indication that they need public funding. -

tom

1.5kThe problem is, that these images don't adequately represent concepts which cannot be represented by images, so all they're doing is making an appeal to the sensibilities of common people who enjoy such phantasms. That they spend a great deal of time and computing power on this is an indication that they need public funding. — Metaphysician Undercover

tom

1.5kThe problem is, that these images don't adequately represent concepts which cannot be represented by images, so all they're doing is making an appeal to the sensibilities of common people who enjoy such phantasms. That they spend a great deal of time and computing power on this is an indication that they need public funding. — Metaphysician Undercover

But that is the actual image which confirmed the discovery of the Higgs boson. -

tom

1.5kHave you ever come across the word "simulation" before? — Metaphysician Undercover

tom

1.5kHave you ever come across the word "simulation" before? — Metaphysician Undercover

Sure, that is HOW scientists create the images and WHAT they use the computing time for.

Because visualisation is such a powerful tool, scientists go to great lengths to visualise aspects of reality they are investigating.

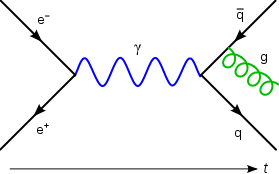

But then again, sometimes they just draw sketches:

-

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kAs I said, these crude visualizations cannot provide one with an understanding of the concepts. These are simply symbols. A depiction of symbols is in no way a visualization of what is meant by the symbols.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kAs I said, these crude visualizations cannot provide one with an understanding of the concepts. These are simply symbols. A depiction of symbols is in no way a visualization of what is meant by the symbols. -

Janus

17.9kdo you recognize that the drawing of the maple leaf you have presented to me is a particular? — Metaphysician Undercover

Janus

17.9kdo you recognize that the drawing of the maple leaf you have presented to me is a particular? — Metaphysician Undercover

Of course it is a particular, but it is not a particular leaf, it is a particular drawing of the generalized form of the maple leaf.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- What is the difference between subjective idealism (e.g. Berkeley) and absolute idealism (e.g. Hegel

- Does Transcendental idealism really imply the concept of noumena?

- Rationalism or Empiricism (or Transcendental Idealism)?

- Idealism and "group solipsism" (why solipsim could still be the case even if there are other minds)

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum