-

ernestm

1koh, well from what you said thats easy to answer. Hypnosis is not possible unless the subject is willing. The deeper question is, why is the subject willing?

ernestm

1koh, well from what you said thats easy to answer. Hypnosis is not possible unless the subject is willing. The deeper question is, why is the subject willing? -

I like sushi

5.4kSo the deeper question is why people are willing to respect authority. I believe I have already outlined my view.

I like sushi

5.4kSo the deeper question is why people are willing to respect authority. I believe I have already outlined my view.

To repeat, if you’re completely subservient to someone then you have little to no responsibility because you’re not making any decisions and therefore nothing is your fault. If you’re in full-blown rebellion then you’re taking on all the responsibility (whether you know it or not) and anything that goes wrong is your fault.

I’m not for a second suggesting reality is anywhere near this black and white, just pointing out that we give up certain ‘freedoms’ to relieve ourselves from the heavy burden of responsibility. We don’t tend to do this willy nilly though, and shift our sense of ‘responsibility’ to an authority figure, or authoritative structure, that we deem more able to cope - our choice is never absent we simply distance ourselves from it in order to ease the stresses and strains of living.

Some people just see an easy option and go for it. Some analyze more. All vary in their attitudes dependent upon the level of import they attach to the circumstances they are in. We never get anything perfectly right, but may see a vision of perfection in ‘what has been’ never in ‘what is’.

The manner in which religious ideas accumulate over time and jump from culture to culture - and/or manifest in the same manner in and of themselves - fascinates me no end.

Maybe we’re not on the same wavelength, either way it is interesting to read your thoughts. -

ernestm

1kwell its the same question, why does someone choose to be totally subservient to someone else? Once theyve chosen so, the results are fairly predictable, but it takes an act of will to choose to give up one's will. Why does someone choose to give up their own will?

ernestm

1kwell its the same question, why does someone choose to be totally subservient to someone else? Once theyve chosen so, the results are fairly predictable, but it takes an act of will to choose to give up one's will. Why does someone choose to give up their own will? -

I like sushi

5.4kOh! You want a different answer to the one I’ve given? Okay ...

I like sushi

5.4kOh! You want a different answer to the one I’ve given? Okay ...

Maybe because they wish to experience something ‘wholly other’. Meaning, as their sense of being and self is essentially tied to their ‘will’ (choices), then absconding and giving themselves over to some ‘other’ may seem appealing. People may do this due to trauma, curiosity and or purely by accident.

Another possible answer ... mmm ...? Do you have any suggestions?

I guess they may have seen someone else do this and they simply like the look of it, or they’ve been living too rigid a life and feel suffocated (there could no end of possible reasons for such a feeling).

However I see it it’s a matter of ‘comfort zones’ and ‘exploration’ and/or the neglect of them. -

ernestm

1kI can see you put alot of effort into writing those, um, 22 words is it? Yes. Well here, let me put the same effort into replying to you as you did reading my first intro post, I know it was long, but if you wish to discuss further, I must ask you actually figure out I already answered your question in my first post.

ernestm

1kI can see you put alot of effort into writing those, um, 22 words is it? Yes. Well here, let me put the same effort into replying to you as you did reading my first intro post, I know it was long, but if you wish to discuss further, I must ask you actually figure out I already answered your question in my first post. -

ernestm

1kI think I need to think about that a while and see what I could say better for you. Could take a day or so )

ernestm

1kI think I need to think about that a while and see what I could say better for you. Could take a day or so ) -

ernestm

1kok. I think I have the right clarification for you. First, here is the current text on the topic which I have improved rather substantially, albeit making it longer:

ernestm

1kok. I think I have the right clarification for you. First, here is the current text on the topic which I have improved rather substantially, albeit making it longer:

(2) Hermeneutic Corroboration

- Hermeneutic: (from Hermes, messenger and soul guide of the Greek Gods): wisdom in interpretation. Hermeneutic theory is "a member of the social subjectivist paradigm where meaning is inter-subjectively created, in contrast to the empirical universe of assumed scientific realism (Berthon et al. 2002). Other approaches within this paradigm are social phenomenology and ethnography. As part of the interpretative research family, hermeneutics focuses on the significance that an aspect of reality takes on for the people under study" (University of Colorado).

In the next section, I will advocate how it is not an unreasonable postulation that Jesus learned of otherwise lost Egyptian medical techniques. First I consider the consequences of Jesus' decision to affect a major change to human spirit, instead of being a doctor in accordance with the talents he displayed. And so it was that Jesus introduced astounding teachings on love and forgiveness that were totally alien to the cultures of the time.

Of Ancient Emotions: Consider for example, in all Roman texts, there was no emotion of guilt. None at all. There was valor, humor, and desires to improve civilization in Stoic manners, but no guilt. It rather surprised me no one observed this before, so I asked a number of knowledgeable friends what they thought. They all expressed, with some surprise, they could think of no example of Romans expressing guilt in all the literature they knew either.

Similarly, the Greeks did not know the emotion of guilt. The Greeks beat their chests and bemoaned the fates they could not escape, but they didn't have any emotional guilt. For the Greeks it was always the fault of other men or Gods, all the way from Helen's abduction to Troy, all the way to Oedipus blinding himself because he did not know he had married his mother and killed his father. The absence of Greek and Roman guilt is one observation I have made which apparently no one has ever thought of before, but on asking my friends knowledgeable in the field, they also cannot remember any examples of Roman or Greek guilt.

Emotional guilt was instead known commonly to the Israelites, who were the first society to attempt a system of rational law based on divine justice (compare to, for example, Draco's tabulation of totally random rules in Athens, 620BCE; and the far more common systems of punishment based solely on opinions of the rulers at the time, without any clear statement at all as to what crimes actually were). Prior to that, there is some idea of guilt in the Egyptian judgment in the afterlife. But it was a very different idea than it is now, based on terror of Gods, whether living or beyond life. When we look back to those eras, we tend to assume everyone had much the same judgments and emotions we have now, but we are looking at an extremely savage time, and the social mechanisms to enable such judgments and emotions to blossom in civilization had not fully evolved.

Of the New Idea of Faith, Hope, and Love: The disparate emotional lives of the various ancient cultures is a frequently ignored fact that circumscribed the doctrines of Jesus. The novelty of his lessons could have been no more than amusing, and simply disappeared, but somehow thew grew with significant alacrity. It remains unclear how his teachings gained so much traction at all, amidst the far louder rhetoric and more powerful means of rich and well-entrenched opponents.

His new ideas resulted in spiritual growth of compassion, and love, together with the positive nature of the afterlife, looked to with hope rather than fear (unlike any other tradition of the time ever). Cultural response of the opponents included Nero's feeding early Christians to lions, because they didn't mind dieing, and the Roman crowds just adored watching it, without any guilt at all. It is impossible to imagine at all how so many people professing faith in Christ would join together in such an apparently defeatist effort, and let themselves be so persecuted. Not only does it beg the question of whether there is no empirical evidence for the Holy Spirit working in the world, but also, regardless that, there must have been some genuine historical antecedence (as perpetuated by the Nicaean council, however one regards the creed they defined). But here, I put aside how much corroboration should be necessary to consider belief in the Holy Spirit as rational too.

New teachings by themselves would not be enough to convince people that another way of life might be better. Even now, people are extremely resistant to changing their mind about virtually anything at all, only scoffing at others being wrong. So it seems to me Jesus'' medical knowledge, described by people of the time as miracles, was totally necessary to affect the change for the better he sought. Some would scorn that as fraudulent, but amidst the ignorance and savagery of the time, I personally do not find it in myself to be so condemnatory.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

So then, now I believe I can pose my thought to you. Why exactly was guilt and forgiveness suddenly so appealing to international cultures which had lived without them for centuries, indeed, over a millennia? If there were not some underlying spiritual force, be it of the human nature or supernatural, guilt and forgiveness would simply have vanished, as unnecessary or unwanted or for whatever reason you may construe, in the panoply of human experience. But those emotions did not disappear, instead they surged with such force that people were fed to lions, when they simply could have left the church. They chose not to. They were so committed to brotherly love they found, that they even let themselves be eaten alive for sport. If there were not some underlying need in the human spirit, whatever that need may actually be, then there would be no reason for such a sudden, dramatic change that swept the Western world. That's how I see it. If it still does not make sense to you, I would be indebted if you would ask for clarification or criticize what I say, because I do feel it is an important observation that has in fact never been made before. -

I like sushi

5.4kI still want to hear your answer/s to the ‘deeper question’ first.

I like sushi

5.4kI still want to hear your answer/s to the ‘deeper question’ first.

You asked why people give up their ‘will’ in reference to people’s ‘respect for authority’ (I removed the ‘religious’ part because I don’t see the importance - authority is authority regardless).

So, why is the subject willing to give up their ‘will’? That’s what you stated as the ‘deeper question,’ so I’d like a direct answer as I’ve given you a few possible answers myself already.

Thanks -

ernestm

1kThe reason I say it is a deeper question is because I cant imagine any way to fully corrobarate any hypotheses as to its answer such that it would be truthful beyond doubt. It seems to me a matter of opinion, and therefore, I ask your opinion on why you think guilt, brotherly love, and forgiveness were so powerful in nature that people let themselves be eaten alive, when they could simply have left the early Christian church.

ernestm

1kThe reason I say it is a deeper question is because I cant imagine any way to fully corrobarate any hypotheses as to its answer such that it would be truthful beyond doubt. It seems to me a matter of opinion, and therefore, I ask your opinion on why you think guilt, brotherly love, and forgiveness were so powerful in nature that people let themselves be eaten alive, when they could simply have left the early Christian church. -

Valentinus

1.6k

Valentinus

1.6k

This is not true. Most of the plays deal with guilt. Plato's Republic chooses culpability over freedom from it.Similarly, the Greeks did not know the emotion of guilt.

You really have no idea what you are talking about. -

I like sushi

5.4kThat’s the opposite of the original question you posed. Christians denied the authority of the Romans willfully. They chose an individual path that opposed the authoritative figure.

I like sushi

5.4kThat’s the opposite of the original question you posed. Christians denied the authority of the Romans willfully. They chose an individual path that opposed the authoritative figure.

Monks set themselves on fire in Vietnam. That is something we do know more about.

Basically you seem to be talking about sacrifice. Maybe ‘Fear and Trembling’ would be a good read for you. I’m not really interested in highly speculative history based solely on religious texts.

As for the ancient Greeks not feeling guilt you’d have to show your thinking more. It is an interesting idea. -

ernestm

1kAdvising me to read 'Fear and Trembling.' lol. Thats really funny. Of course you have not seen 'Christ, the Shit Sponge, and Beyond' so you would not know why it is so funny, but thank you for making me laugh.

ernestm

1kAdvising me to read 'Fear and Trembling.' lol. Thats really funny. Of course you have not seen 'Christ, the Shit Sponge, and Beyond' so you would not know why it is so funny, but thank you for making me laugh.

Maybe it is the opposite of the original question to you. But it is not the opposite of the original question to me. Also monks still set themselves on fire in Tibet. However as you have asked to put aside the issue of religious authority, its not directly pertinent to why people let themselves be eaten alive before there was any religious authority, because, they were doing so in protest that the government had overruled their own religious authorities. The issue of why people would commit themselves so much to brotherly love and forgiveness in a society which previously had not even manifest guilt remains.

I invite you to find an example of guilt in roman and greek texts. As I say, I talked with a number of historians from Oxford, two with PhDs, and they could not think of any example either. -

I like sushi

5.4kThere are plenty of examples in languages new and old where emotional concepts don’t line up on a 1 to 1 basis. To suggest Greeks not having a term specifically for guilt doesn’t mean they didn’t ‘feel’ guilt. Just like lack of the concept of gravity didn’t help them if they fell off a cliff.

I like sushi

5.4kThere are plenty of examples in languages new and old where emotional concepts don’t line up on a 1 to 1 basis. To suggest Greeks not having a term specifically for guilt doesn’t mean they didn’t ‘feel’ guilt. Just like lack of the concept of gravity didn’t help them if they fell off a cliff.

You made an assumption:

On the other hand, it must rely on the fact that people actually want to respect religious authority, which opens a deeper question.

— ernestm

You said ‘must’ and that isn’t necessarily true. It is an assumption. Regardless it boils don’t to the statement that people ‘want to respect religious authority,’ which is again, an assumption without any founding.

Tell me SPECIFICALLY what is the difference between ‘respecting’ religious authority that is intrinsically different from just respecting authority in general. That might help.

Now you’ve switched to Christians and lions. It is not at all difficult to find individual examples (factual or fictional) that align with some original claim. The point being if you make a sweeping statement about humans and religion a singular story doesn’t cut it.

People, humans, are willing to die for a whole host of reasons (revenge, patriotism, god, guilt, etc.,.) That doesn’t mean the reasons they willingly die for are stupid, noble, right, wrong or anything else. As for people dying for a cause they deem worthy, they are making a sacrifice. People, often lovers and parents, have been dying to save others for a long, long time that undoubtedly predates Christianity.

The guilt thing is interesting. References would be useful because some unnamed professors doesn’t give me much to work with. -

Michael Nelson

6I recommend googling Bart Ehrman Vs. Robert Price debate, since they did a debate a few years ago on this very topic. Even though Ehrman is himself agnostic, he has written an entire book arguing that Jesus certainly existed as a person, which, as it happens, is the stance of 99% of 1st century historians.

Michael Nelson

6I recommend googling Bart Ehrman Vs. Robert Price debate, since they did a debate a few years ago on this very topic. Even though Ehrman is himself agnostic, he has written an entire book arguing that Jesus certainly existed as a person, which, as it happens, is the stance of 99% of 1st century historians.

So the idea that Jesus didn't exist doesn't have much scholarly support. But do check out the debate as it contains some good details. -

ernestm

1kWell Im sorry. I thought you wanted to put aside the issue of religious authority. True, even if there is no evidence that Romans or Greeks felt guilt, its possible they did. Nonetheless, in the rather significant volume of literature handed down to us, neither I nor a number of experts in the field have been able to identify one case where someone felt bad about what they did, while thinking it was their own fault. In all cases, it appears always to be the fault of someone else or the Gods, which is in fact, touted as being the truth in the entire body of all Greek tragedy. Considering how much people these days often claim or behave that no criticisms of them are ever their own fault (even extending to the President of the United States now), it does appear this is a topic deserving far more attention than a philosophy forum, so I intend to publish.

ernestm

1kWell Im sorry. I thought you wanted to put aside the issue of religious authority. True, even if there is no evidence that Romans or Greeks felt guilt, its possible they did. Nonetheless, in the rather significant volume of literature handed down to us, neither I nor a number of experts in the field have been able to identify one case where someone felt bad about what they did, while thinking it was their own fault. In all cases, it appears always to be the fault of someone else or the Gods, which is in fact, touted as being the truth in the entire body of all Greek tragedy. Considering how much people these days often claim or behave that no criticisms of them are ever their own fault (even extending to the President of the United States now), it does appear this is a topic deserving far more attention than a philosophy forum, so I intend to publish. -

ernestm

1kWell thank you for the pointer, and perhaps I can add it to references, but really if you will look at my thesis in total, that St. Thomas was an example of a rational skeptic, and there is no room in the church currently for rational skepticism, and instead, huge swaths of ignorant people dismissing the entire story as a myth, AND most people don't even know the gospel of Thomas exists at all; additionally, no one else has even realized, as far as I know, that the sponge offered to Jesus was a shit sponge, nor has anyone noticed the lack of emotional guilt in roman and greek civlizations, and moreover, more points I raise in my other three homiliies have to my knowledge never been discussed either, I have a rather larger issue that simply the likelihood of the texts being about a real person. If anything, I wrote too much on the the comparative quality of the Christian texts, because most people say that part is too long and boring.

ernestm

1kWell thank you for the pointer, and perhaps I can add it to references, but really if you will look at my thesis in total, that St. Thomas was an example of a rational skeptic, and there is no room in the church currently for rational skepticism, and instead, huge swaths of ignorant people dismissing the entire story as a myth, AND most people don't even know the gospel of Thomas exists at all; additionally, no one else has even realized, as far as I know, that the sponge offered to Jesus was a shit sponge, nor has anyone noticed the lack of emotional guilt in roman and greek civlizations, and moreover, more points I raise in my other three homiliies have to my knowledge never been discussed either, I have a rather larger issue that simply the likelihood of the texts being about a real person. If anything, I wrote too much on the the comparative quality of the Christian texts, because most people say that part is too long and boring. -

Michael Nelson

6

Michael Nelson

6

Most people are ignorant about lots of things, not just history so that shouldn't be surprising. However, I don't really think many people doubt that Jesus was at the very least a historical figure. I'd imagine it is a fringe group.

Also your original post made me think of this blog post: https://calumsblog.com/2017/08/11/jesus-secular-sources/

where the guy puts together a nice list of sources and quotes about Jesus from various non-Christian sources. -

ernestm

1kthat may have been true in the past, Michael, but from what I see happening now, with memes and instults so popular in the era of Trump, the sneering minority has become an aggressive majority, per my own experience.

ernestm

1kthat may have been true in the past, Michael, but from what I see happening now, with memes and instults so popular in the era of Trump, the sneering minority has become an aggressive majority, per my own experience. -

I like sushi

5.4kThis sounds very strongly related to themes of ‘guilt’ to me:

I like sushi

5.4kThis sounds very strongly related to themes of ‘guilt’ to me:

... There is nothing more degrading or shameful than a woman who can contemplate and carry out deeds like the hideous crime if murdering the husband of her youth. I had certainly expected a joyful welcome from my children and my servants when I reached home. But now, in the depth of her villainy, she has branded with infamy not herself alone but the whole of her sex, even the virtuous ones, for all time to come.

- The Odyssey, penguin classics, 431

This certainly goes along with your point. It doesn’t really suggest that there was no sense of guilt.

Clearly there is great emphasize on topics like ‘justice’ from both the Romans and the Greek. I could simply argue that people didn’t lie because they had no concept of guilt, but that would be silly.

Guilt, as in a guilty party, clearly existed. If you’re simply saying there was no specific adjective for ‘guilt’ fair enough. If there were crimes, which there were, then there are people who are guilty of such crimes. People would be accused of crimes and claim innocence.

Logically I’d say that ‘to feel guilty’ is a repercussion of common law not something given to humanity from an individual - or ‘guilt’ and ‘remorse’ would be quite alien concepts today.

It is interesting to see that Metanoia meant ‘change of mind’ in Greek.

Note: I’d appreciate it if you gave me some names of the professors you’re referring to. Thanks -

ernestm

1k... There is nothing more degrading or shameful than a woman who can contemplate and carry out deeds like the hideous crime if murdering the husband of her youth. I had certainly expected a joyful welcome from my children and my servants when I reached home. But now, in the depth of her villainy, she has branded with infamy not herself alone but the whole of her sex, even the virtuous ones, for all time to come.

ernestm

1k... There is nothing more degrading or shameful than a woman who can contemplate and carry out deeds like the hideous crime if murdering the husband of her youth. I had certainly expected a joyful welcome from my children and my servants when I reached home. But now, in the depth of her villainy, she has branded with infamy not herself alone but the whole of her sex, even the virtuous ones, for all time to come.

- The Odyssey, penguin classics, 431 — I like sushi

This is exactly what I am saying. Not only is there no record of the Greeks and Romans taking personal responsibility for the things they did wrong themselves and feel bad about it...but now, 2000 years later, a thinking and rational person like yourself cannot even tell when someone is demeaning and degrading their own wife...Instead he blames her for her behavior because of what he did wrong, in this case, if I identify the location of the quote correctly, without even thinking she might be slightly upset about her husband disappearing for seven years to a war she didnt want him to join in the first place. I rest my case. Even today people these days cant tell the difference. YOU can't, lol. Not that I blame you, everyone else does it, but it does show the scale of the problem I am trying to address.

I should actually explain, spell out, and repeat that guilt is not saying someone else is at fault, but taking personal responsibility for a fault. I would also like to include, with your permission, your quote, claiming it is an example of guilt, to illustrate how even now people dont know what it is so well, which may partly explain why no one noticed the absence of guilt in Romans and Greeks before. -

ernestm

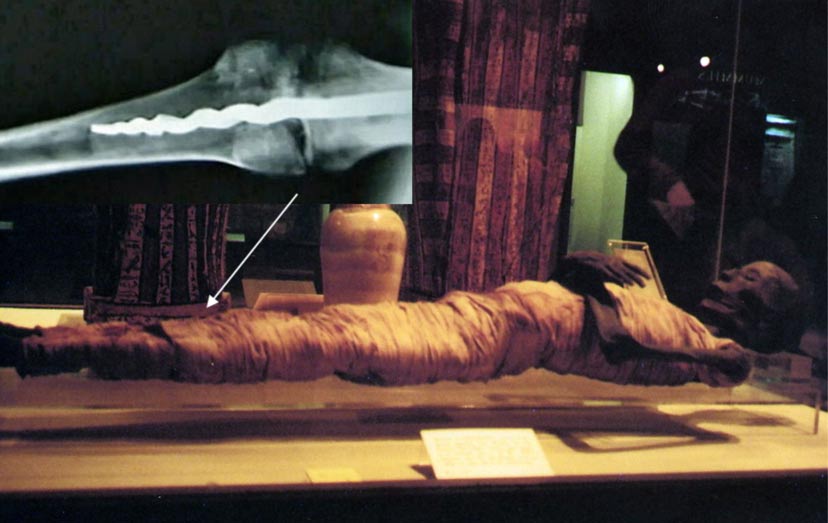

1kCorrection: Ancient Egyptian Surgery was on Knee, not Spine

ernestm

1kCorrection: Ancient Egyptian Surgery was on Knee, not Spine

Apologies my memory since 2003 is off. I had said there is evidence were in posession of many lost advanced medical techniques, which kjesus could have learned from scrolls that his father had obtained from the plundering of the library of Alexandria in the first great fire, 145BCE. So first of all, specifically, the mummy is in the Wikipedia, but the text is currently out of date:

[url=http://]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Usermontu_(mummy)[/url]

Above it states the mummy is from 400BCE, according to carbon darting (I had remembered 1500 BCE). There is a current link on the page to an article stating that a metal pin was used to repair a broken knee before death.

BYU Professor Finds Evidence of Advanced Surgery in Ancient Mummy

[url=http://]https://magazine.byu.edu/article/byu-professor-finds-evidence-of-advanced-surgery-in-ancient-mummy/[/url] BYU Magazine, Brigham Young University, 1996.

And this could be a cause for many's confusion, because the story changed over successive examinations since the first time I heard it. What I remembered was hearing with astonishment that the man lived at least a decade with the pin in his leg. Quote from article:

A BYU professor and a team of specialists discovered an iron pin in the knee of an Egyptian mummy at the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum and Planetarium in San Jose, Calif., evidencing an advanced surgical procedure performed nearly 2,600 years ago.

C. Wilfred Griggs, director of ancient studies at BYU and a professor of ancient scripture, was intrigued by the discovery of the pin in August 1995 when he and a team of experts saw it in the X ray of one of six mummies they were examining at the museum. Griggs was visiting the museum as a precursor to a lecture he was asked to give in San Jose in the fall. When invited to speak, the professor asked if he could first analyze some of the artifacts in their Egyptian museum so he could add a local viewpoint to his talk on the application of science and technology in archaeological field work.

After Griggs’ August visit to the museum, he returned to Provo thinking the 9-inch orthopedic pin was inserted centuries after the death of the mummified body (named Usermontu from an inscription in the coffin in which the body was found). From the X ray taken of the wrapped knee, it was impossible to determine any ancient characteristics of the metal implant.

“I assumed at the time that the pin was modern. I thought we might be able to determine how the pin had been inserted into the leg, and perhaps even guess how recently it had been implanted into the bones,” Griggs says. “I just thought it would be an interesting footnote to say, ‘Somebody got an ancient mummy and put a modern pin in it to hold the leg together.'”

Griggs returned to the museum in November to unwrap the mummy and to determine what he could by visual examination. From this examination of the exposed joint, Griggs and the surgeons who have worked with him now believe the pin was implanted between the time of Usermontu’s death and his burial.

“It didn’t appear to be a modern pin insertion. There were some characteristics of the knee joint, namely some of the ancient fats and textiles, that were still in place and would not have been in place had the leg been separated in modern times,” Griggs says.

Griggs returned to Provo a second time and gathered a team to go to San Jose in February when he and the medical doctors made a full-scale investigation of the mummy, and the team concurred that the pin was ancient and was implanted after Usermontu’s death.

Griggs, Dr. Richard T. Jackson, an orthopedic surgeon from Provo, and Dr. E. Bruce McIff, chief of radiology for Utah Valley Regional Medical Center, drilled the bone containing the pin to try to extract samples of the bone and the metal from the pin.

“We are amazed at the ability to create a pin with biomechanical principles that we still use today—rigid fixation of the bone, for example,” Jackson says. “It is beyond anything we anticipated for that time.”

The pin, says Griggs, tapers into a corkscrew as it enters the femur, or thigh bone, similar to biomechanical methods currently used. The other end of the pin, which is positioned in the tibia, or shin bone, has three flanges extending outward from the core of the pin that prevent rotation of the pin inside the bone.

The cavity for the pin in the tibia also contained a resinous glue that aided in the fixation of the joint, says Griggs, who has excavated in Egypt for more than 15 years and is a historian and ancient texts expert. The team discovered the resin, he says, when a specialist, using a high-tech medical drill, exclaimed that there was wetness inside the bone. The drill bit, moving as fast as 75,000 rpm, had generated enough heat to melt the resinous glue, which is believed to consist of a type of cedar and other organic materials.

The resinous glue also was more advanced than Jackson expected. “It is a precursor of the cement we use these days to secure a total joint.”

Explaining such meticulous effort for a postmortem body, Griggs says Egyptians believed strongly in a physical resurrection. The technician preparing the body, he says, was to make the body appropriate for the reunification of body and spirit.

“How fascinating that the technician took such considerable thought constructing the pin,” he says. “The technician could have just simply wired the leg together and assumed that in the resurrection it would knit back together.”

The pin is a unique find, says Griggs, who has never before encountered anything from the ancient past displaying such advanced surgical understanding or techniques. Griggs says the sophisticated surgery in this mummy suggests that such procedures may have been performed previously on bodies, and the team was fortunate enough to encounter one sample.

In fact, they were fortunate to have access to the mummy. The Rosicrucian Museum acquired Usermontu’s sarcophagus in 1971 when it appeared in a Neiman-Marcus Christmas catalog in a section called “His and Her Gifts for People Who Have Everything.”

The sarcophagus was thought to be empty when a worker heard a rattling from within the sarcophagus during preparation for shipment, museum officials say. The rattling turned out to be an unwrapped ancient mummy inside the coffin. Whether it was originally the body for which the sarcophagus was made cannot be determined. The museum purchased both the mummy and the sarcophagus for $16,000. Before placing the mummy on display, museum curators wrapped the body in ancient linen from other collections in storage.

“It’s a strange story,” Griggs says of Usermontu’s discovery. Griggs believes the sarcophagus was probably not the original tomb used for the burial of Usermontu.

But the story of the mummy’s acquisition may not be as intriguing as the implications of its existence.

“The story tells us how sophisticated ancient people really were,” Griggs says. “Sometimes our cultural arrogance gets in the way of our being able to appreciate how people from other cultures and times were able to also think and act in quite amazing ways.

“The story has so many ramifications for how we look at the past. It also tells us how little we truly know.”

Most bizarrely, a more recent article from 2015 explains more details about the pin, claiming it was inserted after death instead, but quotes the above article as source. -

ernestm

1kOn Thucidides REconstructing Speeches

ernestm

1kOn Thucidides REconstructing Speeches

I did not quite represent this correctly. From Thuc. 1:22:

"As to the various speeches made on the eve of the war, or in its course, I have found it difficult to retain a memory of the precise words which I had heard spoken; and so it was with those who brought me reports. But I have made the persons say what it seemed to me most opportune for them to say in view of each situation; at the same time, I have adhered as closely as possible to the general sense of what was actually said. As to the deeds done in the war, I have not thought myself at liberty to record them on hearsay from the first informant, or on arbitrary conjecture. My account rests either on personal knowledge, or on the closest possible scrutiny of each statement made by others. The process of research was laborious, because conflicting accounts were given by those who had witnessed the several events, as partiality swayed or memory served them."

The specific problem to scholars remains, Thucydides never indicates which speeches he recalled from hearing in person, and which speeches were reported to him. Stucturalist analysis of the speeches could reveal no differences in the prose at all. -

I like sushi

5.4kEven today people these days cant tell the difference. YOU can't, lol. Not that I blame you, everyone else does it, but it does show the scale of the problem I am trying to address. — ernestm

I like sushi

5.4kEven today people these days cant tell the difference. YOU can't, lol. Not that I blame you, everyone else does it, but it does show the scale of the problem I am trying to address. — ernestm

Huh? I literally just pointed out the difference between guilt and being guilty. The Greeks tended to use sorrow. If you think I thought you were just talking about ‘guilt’ in general you’re quite wrong. I mentioned guilt because - obviously - feeling guilty about an action is related to guilt. ‘Feeling guilty’ necessarily requires an appreciation of guilt.

I should actually explain, spell out, and repeat that guilt is not saying someone else is at fault, but taking personal responsibility for a fault. — ernestm

Absolutely no need to. I know exactly what it means. There is a hell of a lot more to feeling guilty than just that.

Note: you’ve still not given me the name of a single professor? I I’d also still like to know what is specifically different about ‘religious authority’ compared to ‘authority’ in general?

If you ‘rest your case’ on this it’s a poor case. It follows, in my mind, that feelings of guilt extend from common law, which extends from natural empathy through the so-called ‘social contract’.

I’m curious, do you believe there are instances where feelings of guilt were presented in cultures not influence by Christian society?

You do realise that no human could walk on that leg? The ‘joint’ certainly wasn’t fixed, unless the meaning of ‘fixed’ was ‘fastened and immobile’. There are records of surgeons in ancient Rome dealing with brain clots quite effectively though - they were capable due to the gladiatorial traditions and centuries of bloody warfare. -

ernestm

1klet me try this addition: "Even when Romans and Greeks were shamed by others, they still did not believe it their own fault. They blamed the Gods or other people for all their faults. They never took personal responsibility for anything they did wrong, and if given the chance, would only complain, extensively if possible, about how they had been wrongly abused at the hands of man and the divine."

ernestm

1klet me try this addition: "Even when Romans and Greeks were shamed by others, they still did not believe it their own fault. They blamed the Gods or other people for all their faults. They never took personal responsibility for anything they did wrong, and if given the chance, would only complain, extensively if possible, about how they had been wrongly abused at the hands of man and the divine."

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum