-

Pfhorrest

4.6kEDIT: This thread was originally supposed to be about systemic philosophical principles generally, but it turned into a discussion about my principles specifically. I do want to talk about that, but I also want to talk about systemic principles generally, so I'm repurposing this thread into one about my own principles, and starting another one about systemic principles generally.

Pfhorrest

4.6kEDIT: This thread was originally supposed to be about systemic philosophical principles generally, but it turned into a discussion about my principles specifically. I do want to talk about that, but I also want to talk about systemic principles generally, so I'm repurposing this thread into one about my own principles, and starting another one about systemic principles generally.

My core principles are:

- That there is such a thing as a correct opinion, in a sense beyond mere subjective agreement. (A position I call "objectivism", and its negation "nihilism".)

- That there is always a question as to which opinion, and whether or to what extent any opinion, is correct. (A position I call "criticism", and its negation "fideism".)

- That the initial state of inquiry is one of several opinions competing as equal candidates, none either winning or losing out by default, but each remaining a live possibility until it is shown to be worse than the others. (A position I call "liberalism", and its negation "cynicism".)

- That such a contest of opinion is settled by comparing and measuring the candidates against a common scale, namely that of the experiential phenomena accessible in common by everyone, and opinions that cannot be thus tested are thereby disqualified. (A position I call "phenomenalism", and its negation "transcendentalism").

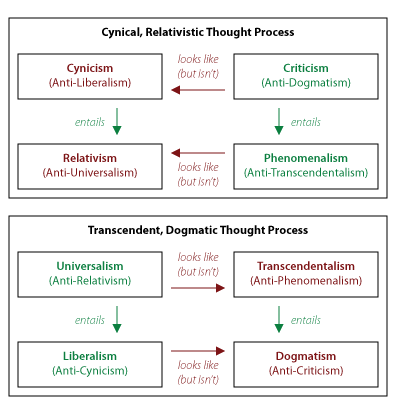

(UPDATE FROM 9MO IN THE FUTURE: I've since revised my terminology, and since the image linked below now reflects that change, I've edited this note in to clarify. Instead of "objectivism vs nihilism", I now use the terms "universalism vs relativism", and consider universalism a type of objectivism alongside transcendentalism, and nihilism a type of relativism as well. Instead of "criticism vs fideism", I now use the terms "criticism vs dogmatism", and consider dogmatism a type of fideism alongside liberalism. Together with the remaining positions, this groups everything into four sets of two:

- Objectivism, which includes both universalism :up: and transcendentalism :down:,

- Subjectivism, which includes both phenomenalism :up: and relativism :down:,

- Fideism, which includes both liberalism :up: and dogmatism :down:, and

- Skepticism, which includes both criticism :up: and cynicism :down:)

I think that these principles necessitate things like:

- An empirical realist ontology

- A functionalist and panpsychist philosophy of mind

- A critical rationalist or falsificationist epistemology

- A freethinking philosophy of education

- A hedonic altruist account of ethical ends

- A compatibilist and pan-libertarian philosophy of will

- A liberal or libertarian account of ethical means

- An anarchic political philosophy

And I see two different common errors that I think underlie all of the positions that I find wrong:

On the one hand, those who reject nihilism, as I do, and correctly adopt its negation, objectivism, but wrongly equate phenomenalism with nihilism and thus objectivism with transcendentalism, then correctly see that transcendentalism entails fideism, and so conclude that the only alternative to nihilism is fideism. If they likewise correctly see that rejecting nihilism entails rejecting cynicism, but wrongly equate criticism with cynicism and thus liberalism with fideism, they will likewise conclude that the only alternative to nihilism is fideism. In either case, from their correct rejection of nihilism, they find themselves seemingly but wrongly compelled to adopt fideism.

I think that this error underlies views like:

- A supernaturalist ontology

- A dualist philosophy of mind

- A fideistic epistemology

- A religious philosophy of education

- A puritanical account of ethical ends

- A metaphysically libertarian philosophy of will

- An absolutist account of ethical means

- An authoritarian political philosophy

On the other hand, those who reject fideism, as I do, and correctly adopt its negation, criticism, but wrongly equate liberalism with fideism and thus criticism with cynicism, then correctly see that cynicism entails nihilism, and so conclude that the only alternative to fideism is nihilism. If they likewise correctly see that rejecting fideism entails rejecting transcendentalism, but wrongly equate objectivism with transcendentalism and thus phenomenalism with nihilism, they will likewise conclude that the only alternative to fideism is nihilism. In either case, from their correct rejection of fideism, they find themselves seemingly but wrongly compelled to adopt nihilism.

I think that this error underlies views like:

- A nihilistic ontology

- An eliminativist philosophy of mind

- A justificationist epistemology

- An "epistemic anarchy" philosophy of education

- An egotistic account of ethical ends

- A hard determinist philosophy of will

- A consequentialist account of ethical means

- An anomic political philosophy

(ALSO UPDATE FROM 9MO IN THE FUTURE: looking back here I realize that because of reasons, a bunch of what was supposed to be in the OP got left out way back when: I've now posted it in a followup comment below, at: https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/513602). -

Isaac

10.3kMy core principles are...

Isaac

10.3kMy core principles are...

That such a contest of opinion is settled by comparing and measuring the candidates against a common scale, namely that of the experiential phenomena accessible in common by everyone, and opinions that cannot be thus tested are thereby disqualified. (A position I call "phenomenalism", and its negation "transcendentalism"). — Pfhorrest

What possible reason could you have to believe that experiential phenomena are a 'common scale', when virtually all the evidence we have seems to point to the contrary with regards to the questions of philosophy.

1. No major philosophical question has been resolved to anyone's satisfaction despite over a thousand years of equally intelligent people attempting to do so. If equally intelligent people maintain these difference despite the longest examination period of any topic in human history, it is blind faith to conclude anything other than that our phenomenal experiences by which we judge the conclusions are actually different in this regard.

2. If (1) wasn't enough, psychological evidence working with neonates shows distinct enculturation of concepts even as simple as object permanence. Something as fundamental as the means by which we navigate 3d space etc might well be hard-wired, but pretty much everything else is an interaction between the child and their social environment.

For someone so opposed to fideism, you seem to have taken a massive leap of faith here, which makes the remainder of your anti-fideism seem rather pointless. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kDo you not understand that what I am advocating there is just basically empiricism? Slightly more abstracted, as on normative questions I also advocate appeal to hedonic experiences in a way analogous to the appeal to empirical experiences on factual questions.

Pfhorrest

4.6kDo you not understand that what I am advocating there is just basically empiricism? Slightly more abstracted, as on normative questions I also advocate appeal to hedonic experiences in a way analogous to the appeal to empirical experiences on factual questions.

I'm not saying that philosophical questions should be settled by appeal to people's intuition from their life experiences, I'm saying that a core philosophical answer (that I'm not presenting an argument for here, just stating that it's the answer I settled on), an answer to a question about how to answer questions, is "answer them by appealing to the phenomenal experiences that people have in common".

Also note that I didn't say "experiential phenomena, which are all accessible in common by everyone", but "[those] experiential phenomena [that are] accessible in common by everyone". Experiences that others don't share are no grounds for answering questions, e.g. observations that aren't repeatable are not admissible evidence. -

Isaac

10.3k

Isaac

10.3k

Well then you're describing science, not philosophy. Science models phenomena and judges those models by their correlation which the sorts of phenomenal experiences we share (mostly sensory perceptions).

I'm not saying that philosophical questions should be settled by appeal to people's intuition from their life experiences, I'm saying that a core philosophical answer (that I'm not presenting an argument for here, just stating that it's the answer I settled on), an answer to a question about how to answer questions, is "answer them by appealing to phenomenal experiences". — Pfhorrest

So you're saying that the answer to the question "how should we settle questions" is "by reference to common phenomenal experience", which is science. Isn't that just positivism? Not that that's a problem, just that it seems a rather long way round of revisiting a prior philosophical tradition. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kWell then you're describing science, not philosophy — Isaac

Pfhorrest

4.6kWell then you're describing science, not philosophy — Isaac

I'm saying that my philosophical position is one that embraces the methods of science... for answering factual or descriptive questions, and analogous methods for answering normative or prescriptive questions.

Science and philosophy don't have to be at odds. In defending why you should do science instead of something else, you're doing philosophy.

So you're saying that the answer to the question "how should we settle questions" is "by reference to common phenomenal experience", which is science. Isn't that just positivism? Not that that's a problem, just that it seems a rather long way round of revisiting a prior philosophical tradition. — Isaac

It's much like positivism, when it comes to descriptive questions. But unlike positivists, I don't take descriptions to be the only meaningful kinds of speech-acts, and I have a whole analogous part of my philosophy that approaches prescriptions in a way analogous to how positivists approach descriptions.

Positivists generally commit the errors I ascribe to "nihilism" (as defined here) when approaching normative or prescriptive questions. My principles are meant to be broader abstractions of ones similar to positivist principles, in a way that doesn't ab initio rule out the possibility of answering ethical questions. -

Isaac

10.3kanalogous methods for answering normative or prescriptive questions. — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kanalogous methods for answering normative or prescriptive questions. — Pfhorrest

In defending why you should do science instead of something else, you're doing philosophy. — Pfhorrest

So by what should the correctness of answers to these questions be judged, if not common phenomenal experience (which we've just established is science)? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo by what should the correctness of answers to these questions be judged, if not common phenomenal experience (which we've just established is science)? — Isaac

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo by what should the correctness of answers to these questions be judged, if not common phenomenal experience (which we've just established is science)? — Isaac

Appeal to common phenomenal experience to answer descriptive questions is (physical) science. But as I already said earlier,

...and in that establish the groundwork for ethical sciences: not physical (empirical) sciences applied to ethical questions, but an analogous kind of investigation, appealing to experiences of things seeming good or bad instead of experiences of things seeming true or false, to put it roughly.on normative questions I also advocate appeal to hedonic experiences in a way analogous to the appeal to empirical experiences on factual questions. — Pfhorrest

I was about to edit this into my previous comment before you responded: Positivists also err (in my view) on some descriptive topics too. They generally don't embrace the principle I called "liberalism" when it comes to descriptive questions, and so fall into a justificationist epistemology; and they also tend to be eliminativists about philosophy of mind. -

Isaac

10.3kan analogous kind of investigation, appealing to experiences of things seeming good or bad — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kan analogous kind of investigation, appealing to experiences of things seeming good or bad — Pfhorrest

It's pretty evident I think that the matter of things 'seeming' some way or other ('good' or 'bad' in this case) is exactly the kind of matter where there is very little by way of shared phenomenal experience. What makes you think you'd find any here? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThere are plenty of cases of shared agreement about things "seeming good or bad" as in sharing the same hedonic experience of the same phenomenon. Many of the same kinds of thing cause pain, hunger, etc, all kinds of hedonic experiences, in most people.

Pfhorrest

4.6kThere are plenty of cases of shared agreement about things "seeming good or bad" as in sharing the same hedonic experience of the same phenomenon. Many of the same kinds of thing cause pain, hunger, etc, all kinds of hedonic experiences, in most people.

There are outliers, of course, but there are also blind and deaf people when it comes to empirical experience, and we can account for that. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kYou get that when I say "seeming good or bad", I don't mean you look at some situation not involving you and "sense" its morality, right? We don't confirm empirical observations by looking at the people making the observation and intuiting whether they seem to have it right or not. We confirm them by standing in the same place as them and seeing if we see the same things. Likewise, you confirm a hedonic experience by standing in the same circumstance as someone who reported having it and seeing if you feel the same way in that circumstance. If so, then that's "ethical data" that needs to be accounted for.

Pfhorrest

4.6kYou get that when I say "seeming good or bad", I don't mean you look at some situation not involving you and "sense" its morality, right? We don't confirm empirical observations by looking at the people making the observation and intuiting whether they seem to have it right or not. We confirm them by standing in the same place as them and seeing if we see the same things. Likewise, you confirm a hedonic experience by standing in the same circumstance as someone who reported having it and seeing if you feel the same way in that circumstance. If so, then that's "ethical data" that needs to be accounted for. -

Isaac

10.3kThere are plenty of cases of shared agreement about things "seeming good or bad" as in sharing the same hedonic experience of the same phenomenon. Many of the same kinds of thing cause pain, hunger, etc, all kinds of hedonic experiences, in most people. — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kThere are plenty of cases of shared agreement about things "seeming good or bad" as in sharing the same hedonic experience of the same phenomenon. Many of the same kinds of thing cause pain, hunger, etc, all kinds of hedonic experiences, in most people. — Pfhorrest

Yes, but there's is not a shared phenomenal experience that pain is 'bad'. Many people seems to expect the use of the term 'bad' to do something other than refer to pain. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kYes, but there's is not a shared phenomenal experience that pain is 'bad'. — Isaac

Pfhorrest

4.6kYes, but there's is not a shared phenomenal experience that pain is 'bad'. — Isaac

If something doesn’t feel bad, how can it be called pain? Pain, or suffering more generally, is a bad-feeling experience.

Many people seems to expect the use of the term 'bad' to do something other than refer to pain. — Isaac

Many people seem to expect the use of the term “real” to do something other than refer to observables. Those people are rejecting empiricism, and I think they’re wrong. Likewise, people who think that things can be bad even though they hurt nobody reject hedonism, and I think they’re wrong.

NB again that I am not arguing for these positions here right now, just stating that they are my positions and clarifying what they are. Of course people who disagree with those positions think differently. I think it can be shown that they are wrong. That’s how disagreement works. -

Isaac

10.3kIf something doesn’t feel bad, how can it be called pain? Pain, or suffering more generally, is a bad-feeling experience. — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kIf something doesn’t feel bad, how can it be called pain? Pain, or suffering more generally, is a bad-feeling experience. — Pfhorrest

Not in the sense 'bad' is used when talking about morals. In that sense, some people think pain is 'good' (retribution, just suffering, self-flagellation...).

people who think that things can be bad even though they hurt nobody reject hedonism, and I think they’re wrong. — Pfhorrest

Fine.

I think it can be shown that they are wrong. That’s how disagreement works. — Pfhorrest

That's circular. We're discussing whether these matters are amenable to judgement by measure against shared phenomenal experience (the measure you proposed for the resolution of conflicting arguments). So you can't then claim that people who have a different phenomenal experience are wrong, that just immunises your argument against any critique.

There are people whose phenomenal experience of what seems 'bad' does not equate with hedonic sensations. They feel (or see) pain and do not feel that it is 'bad', in a moral sense. That's their phenomenal experience. If you're going to start saying they're wrong then you're doing just that which you decried at the beginning. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThey feel (or see) pain and do not feel that it is 'bad', in a moral sense. — Isaac

Pfhorrest

4.6kThey feel (or see) pain and do not feel that it is 'bad', in a moral sense. — Isaac

It seems to me that you are still mistaking what I’m talking about in the way I already clarified here:

You get that when I say "seeming good or bad", I don't mean you look at some situation not involving you and "sense" its morality, right? We don't confirm empirical observations by looking at the people making the observation and intuiting whether they seem to have it right or not. We confirm them by standing in the same place as them and seeing if we see the same things. Likewise, you confirm a hedonic experience by standing in the same circumstance as someone who reported having it and seeing if you feel the same way in that circumstance. If so, then that's "ethical data" that needs to be accounted for. — Pfhorrest -

Isaac

10.3kyou confirm a hedonic experience by standing in the same circumstance as someone who reported having it and seeing if you feel the same way in that circumstance. If so, then that's "ethical data" that needs to be accounted for. — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kyou confirm a hedonic experience by standing in the same circumstance as someone who reported having it and seeing if you feel the same way in that circumstance. If so, then that's "ethical data" that needs to be accounted for. — Pfhorrest

Whether hedonic experience equates to moral 'good' and 'bad' is the matter in dispute. You cannot resolve that issue using the method you outlined because there is no shared phenomenal experience of hedonic experience equating to moral 'good' and 'bad'. The feeling that it does/doesn't varies widely. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhether hedonic experience equates to moral 'goid' and 'bad' is the matter in dispute. You cannot resolve that issue using the method you outlined because there is no shared phenomenal experience of hedonic experience equating to moral 'good' and 'bad'. The feeling that it does/doesn't varies widely. — Isaac

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhether hedonic experience equates to moral 'goid' and 'bad' is the matter in dispute. You cannot resolve that issue using the method you outlined because there is no shared phenomenal experience of hedonic experience equating to moral 'good' and 'bad'. The feeling that it does/doesn't varies widely. — Isaac

You are still conflating two different things here. What you are asking for is like asking to empirically prove that empiricism is correct. I am not saying that you can do that, or that you can hedonically prove that hedonism is correct. I am saying that I take hedonism to be the correct way to tell whether things are normatively correct, in the same way that I take empiricism to be the correct way of telling whether things are factually correct. I haven’t presented arguments for either of those positions here, just said that they are my positions.

This thread isn’t about justifying my philosophical principles, I only gave them as an example of the kind if systemic principles this thread is supposed to be about.

Maybe this will help clarify more what those principles are, if it will settle this tangent down. Those four principles applied specifically to normative or prescriptive questions mean:

Phenomenalism: it’s experiences of pain, pleasure, suffering, enjoyment, etc — things feeling good or feeling bad — that matter in determining whether something is good or bad.

Objectivism: Everyone’s such experiences matter equally, without bias.

Liberalism: All intentions/actions are to be considered permissible by default until they can be shown wrong as above.

Criticism: Any intention/action could in principle be shown wrong like that; none are beyond question.

And again, I’m not saying that these principles can be used to prove themselves. I’m not trying to prove them in this thread, I’m just stating what they are as an example. -

Enrique

845

Enrique

845

Maybe you need to include a cultural dimension also. Reading this, I began to consider that what binds human behavior isn't simply the desire for pleasure or lack of suffering in the individual, but pursuit of collective control along with concessions and compromises to sustain that control in the face of everyone's subcultural weakness, which is what makes the difference between a kinship clan and an institutional framework. Not necessarily a rational social contract, but a pragmatic baseline level of respect for the implications of what contrasting social groups want or do. Perhaps civilization is not even possible without this not hedonic but communal sensibility, no matter how hardnosed the participants are. This communality could be a very tenuous phenomenon at best, but perhaps certain conditions in education and elsewhere can foster its enhancement. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThat sounds like the kind of thing that my principles of objectivism and liberalism would imply: everybody‘s perspective matters equally, and differences are acceptable until they can be shown otherwise. When applied to the topic of political philosophy I end up with something much like you describe.

Pfhorrest

4.6kThat sounds like the kind of thing that my principles of objectivism and liberalism would imply: everybody‘s perspective matters equally, and differences are acceptable until they can be shown otherwise. When applied to the topic of political philosophy I end up with something much like you describe. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI don’t think the principles themselves can show that those who disagree with them are wrong. That would be nonsense and circular. I think that the principles can be shown correct, with arguments that don’t appeal to those principles themselves. Arguments I’m not going into here because this thread isn’t about that.

Pfhorrest

4.6kI don’t think the principles themselves can show that those who disagree with them are wrong. That would be nonsense and circular. I think that the principles can be shown correct, with arguments that don’t appeal to those principles themselves. Arguments I’m not going into here because this thread isn’t about that.

Again, you can’t expect empiricism to prove that empiricism is correct, but that doesn’t mean there can be no arguments that empiricism is correct; and its inability to prove itself solely by appeal to itself is no argument against it. -

Isaac

10.3k

Isaac

10.3k

So another of your core principles is that there's a clandestine second way to resolve conflicts of opinion which you're going to leave out of your core principles because... -

jgill

4kThat there is such a thing as a correct opinion, in a sense beyond mere subjective agreement. (A position I call "objectivism", and its negation "nihilism".) — Pfhorrest

jgill

4kThat there is such a thing as a correct opinion, in a sense beyond mere subjective agreement. (A position I call "objectivism", and its negation "nihilism".) — Pfhorrest

Sorry to intrude. I am not a philosopher, but I am not sure what you mean, here. For example, in the philosophy of morals or ethics, what is the "correct" opinion regarding Sophie's Choice? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThere can possibly be morally intractable situations where every extant possibility is bad. Objectivism with regards to such situations just means that it is objectively correct to say of each option that it is bad: that someone who thinks one (or both) of the options is good is incorrect.

Pfhorrest

4.6kThere can possibly be morally intractable situations where every extant possibility is bad. Objectivism with regards to such situations just means that it is objectively correct to say of each option that it is bad: that someone who thinks one (or both) of the options is good is incorrect.

In the case of the literal Sophie’s Choice from the book, it’s probably the case that either choice of child is a less-bad option than letting both children die, even though all options are bad to some extent. In general, if you can’t save everybody, saving somebody is still better than saving nobody. That doesn’t excuse that not saving some people is still a bad outcome (though not necessarily reflective of bad choices on anybody’s part, if there was nothing anybody could do about it; though in the case in the book, it’s the Nazis who are ultimately at fault, of course). -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kThe first head-scratcher for me is the compatibility of objectivism with phenomonalism. Isn't the acceptance of the phenomological limit rather at odds with the idea that I have direct sensation of reality? And why do I need to even appeal to shared phenomena if my knowledge is objective? And is a philosophy of what's-right-for-me truly compatible with liberalism? For instance, can:

Kenosha Kid

3.2kThe first head-scratcher for me is the compatibility of objectivism with phenomonalism. Isn't the acceptance of the phenomological limit rather at odds with the idea that I have direct sensation of reality? And why do I need to even appeal to shared phenomena if my knowledge is objective? And is a philosophy of what's-right-for-me truly compatible with liberalism? For instance, can:

the initial state of inquiry is one of several opinions competing as equal candidates, none either winning or losing out by default, but each remaining a live possibility until it is shown to be worse than the others — Pfhorrest

be said to be compatible with objectivism? So as for the second "error", I'm sympathetic.

Other than that, I share the same core principles, and notice similar patterns. It strikes me that the first set of converse positions also often share a view that my principles somehow undermine something precious: absolutism, idealism, mysticism. It's always a sense of tearing something down rather than building something up: in a word, conservativism. So I wonder if the seeming error is a symptom rather than a cause. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe first head-scratcher for me is the compatibility of objectivism with phenomonalism. Isn't the acceptance of the phenomological limit rather at odds with the idea that I have direct sensation of reality? And why do I need to even appeal to shared phenomena if my knowledge is objective? — Kenosha Kid

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe first head-scratcher for me is the compatibility of objectivism with phenomonalism. Isn't the acceptance of the phenomological limit rather at odds with the idea that I have direct sensation of reality? And why do I need to even appeal to shared phenomena if my knowledge is objective? — Kenosha Kid

My principle of objectivism isn’t saying that we have direct experience of (the whole of) reality (or morality), or that all our thoughts are objectively correct. Just that there is something that it would be objectively correct to think, as opposed to saying there is no correct or incorrect and every opinion is just as baseless as any other.

Your use of “limit” is apropos here, because on my account objectivity is the limit (in a mathematical sense) of progressively less wrong opinions, what our opinions converge toward as we take more and more experiences into proper account, but which we can never quite reach.

And is a philosophy of what's-right-for-me truly compatible with liberalism? For instance, can:

the initial state of inquiry is one of several opinions competing as equal candidates, none either winning or losing out by default, but each remaining a live possibility until it is shown to be worse than the others

— Pfhorrest

be said to be compatible with objectivism? — Kenosha Kid

I’d say liberalism is actually entailed by objectivism: if you are going to hold that such a thing as a correct opinion is possible, you have to give every opinion the benefit of the doubt that that one might possibly be it, otherwise you would be forced to dismiss all opinions as equally incorrect out of hand, i.e. cynicism. (At least, unless you're willing to also reject criticism for fideism, and say that there are simply some foundational opinions that are beyond question).

Likewise phenomenalism, as anti-transcendentalism, is entailed by criticism: if you are going to hold every opinion open to question, you have to consider only opinions that would make some experiential, phenomenal difference, where you could somehow tell if they were correct or incorrect. (At least, unless you're willing to also reject objectivism for nihilism, and say that there are some questions about things beyond experience that simply can never be answered). -

Isaac

10.3kTell me how you justify empiricism without appeal to empiricism. — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kTell me how you justify empiricism without appeal to empiricism. — Pfhorrest

I don't think I would. I think empiricism about the external world is something which cannot really be doubted, so I don't think it requires a justification. But that's not the point. What you're doing with your meta-ethics is not merely advocating a method (though you phrase it that way), you are making a proposition about the shared world - that the moral sentiments 'good' and 'bad' equate to the physiological sensations 'pleasure' and 'pain' in some exhaustive way. This proposition itself is contrary to your empiricism with regards to facts about what is the case in the shared world. It does not itself form an opinion which can be resolved by reference to shared phenomenal experience, and yet it is a statement about what is the case. So I'm not saying that everything (including your foundational principles) must be justified - that would set up an impossible task. I'm saying that, at the very least, your foundational principles should not be built on a belief which itself contradicts one of those very principles.

Say if I was a radical Christian biblical literalist. It would be unreasonable for anyone to expect me to find proof in the bible that I ought to believe everything in the bible. The decision to believe everything in the bible must come first. But if I were to say "I believe everything in the bible because my version was published by Collins and they're the new Messiah", we could justifiably cry foul. The Bible - the very thing I believe every word of - says the opposite.

You're doing the same with your ethics. You're saying on the one hand that a core principle is that we should dismiss from discussion anything which cannot be adjudicated by reference to a common phenomenal experience, and then on the the other you're presenting something as the case (and claiming to be able to argue for it) that is absolutely not judicable by reference to common phenomenal experience. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2k

Kenosha Kid

3.2k

Ahh phew, not Ayn Rand Objectivism, but Objectivity. This is still an extreme end of a scale for me. For instance, if we take a human moral question, this presumably has an exact and true answer. One would expect, probably rightly, that, all other things being amenable, the consensus-driven progress of actual human answers to that question, as implemented by legislature say, would approach that correct answer, but not necessarily expect them to ever reach it. It would seem odd to me for some alien anthropologists to take a view that, whatever it is, there was a right answer to a human question that did not exist at any time during the lifetime of humanity.

I come from a more relativist, structuralist, pragmatist, and ontologically minimalist angle which, to me anyway, also seems consistent with empiricism and phenomonology. It is not that I disbelieve that some phenomonological thing has an underlying objective reality necessarily, more that it's easier to dismiss false beliefs about that reality than it is to justify good ones. Unlike moral questions, physical questions may have an objective answer but, like moral questions, the meaning is always deferred. And even well-founded moral beliefs such as the golden rule are difficult to justify on a cosmological scale, an example of relativism.

The "errors" I see are in phrasing questions that at best can only have contingent answers and at worst are effectively meaningless, particularly ones in which actual experience and empirical facts are deemed unimportant to the question. Anthropocentricism I think is one of the most the most pernicious errors, underpinning much of the three errors mentioned in my last post, as making a virtue of a human bias is wont. I think these would be alleviated by a healthy dose of relativism, phenomonology, scepticism and pragmatism.

Most of my position comes from my background in science, that great human decenterer and natural relativist and pragmatist. I think the only thing that doesn't, my structuralism, comes from my interests in other sciences such as anthropology, and from my enjoyment of postmodern art, particularly literature and, weirdly in my partner's view, ceramics. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI think empiricism about the external world is something which cannot really be doubted, so I don't think it requires a justification. — Isaac

Pfhorrest

4.6kI think empiricism about the external world is something which cannot really be doubted, so I don't think it requires a justification. — Isaac

And yet plenty of people doubt it. People believe in supernatural things that can’t be empirically tested, and disbelieve things that have stood up to empirical testing, all the time. Most people, probably. But we who advocate for science say that those people are wrong. I think arguments can be given for why they’re wrong; arguments that don’t beg the question by presupposing empiricism.

I’m just applying the exact same process to normative questions and hedonic experiences. Most people agree on some level that pain is bad, just like most people generally believe their eyes. But then they also go on to think that all kinds of things that hurt nobody are bad, and things that do hurt people are okay. I think that’s wrong just like people who disbelieve empiricism are wrong, and that arguments to that effect can be given, arguments that don’t beg the question by presupposing hedonism.

you're presenting something as the case (and claiming to be able to argue for it) that is absolutely not judicable by reference to common phenomenal experience. — Isaac

You keep making this category mistake, here and other times this has come up. Common phenomenal experience doesn’t JUST mean empiricism. I am absolutely not saying that hedonism can be empirically proven. Hedonic experiences are a KIND of phenomenal experience, the prescriptive analogue to the descriptive kind of experience we call empirical. I am saying that appeal to common (shared) experiences of that kind is how to settle normative questions, just like appeal to our common (shared) empirical experiences is how to settle factual questions. Lots of people disagree with both if those “how to”s, but I think they can be shown wrong; without begging the question by assuming either kind of phenomenal appeal. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kIt would seem odd to me for some alien anthropologists to take a view that, whatever it is, there was a right answer to a human question that did not exist at any time during the lifetime of humanity. — Kenosha Kid

Pfhorrest

4.6kIt would seem odd to me for some alien anthropologists to take a view that, whatever it is, there was a right answer to a human question that did not exist at any time during the lifetime of humanity. — Kenosha Kid

At first glance I read this as a comment about there being correct answers to “human questions” that predate the existence of humanity, but on second glance I can’t parse this correctly. Maybe you can rephrase?

If it did mean what I initially took it to mean, then I’d say the only answers that existed to human moral questions prior to humanity itself were conditionals. Like today, we can say that supposing we artificially created some kind of life form vastly different from humanity, such-and-such would be the correct answer to a moral question that might come up in such a species’ culture. But that species doesn’t exist yet. Likewise, it can have been true for all time that if humans do such-and-such to other humans it is bad, even if no actual humans exist yet, or anymore. It’s just kind of a useless truth when there aren’t any humans.

It is not that I disbelieve that some phenomonological thing has an underlying objective reality necessarily, more that it's easier to dismiss false beliefs about that reality than it is to justify good ones. — Kenosha Kid

That is exactly the implications of my principles, both about reality, and about morality. Initially anything goes, but options can be weeded out, by showing them in conflict with experience, and the more options we weed out by accounting for more and more experiences, the more we narrow in on the correct answer. I think you already get what that means for investigating reality. For morally, it roughly means that everything is permissible until it can be shown to hurt someone, and the more and more such hedonic experiences we account for, the narrower and narrower the range of still-permissible options remaining, closing in on (but never reaching) the correct answer to the question of what we should do. -

Isaac

10.3kam absolutely not saying that hedonism can be empirically proven. Hedonic experiences are a KIND of phenomenal experience, the prescriptive analogue to the descriptive kind of experience we call empirical. I am saying that appeal to common (shared) experiences of that kind is how to settle normative questions — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kam absolutely not saying that hedonism can be empirically proven. Hedonic experiences are a KIND of phenomenal experience, the prescriptive analogue to the descriptive kind of experience we call empirical. I am saying that appeal to common (shared) experiences of that kind is how to settle normative questions — Pfhorrest

It's not about whether hedonic experiences are shared, it's about whether the feeling that they relate to 'goodness' and 'badness' is shared, which you skip over with...

Most people agree on some level that pain is bad, just like most people generally believe their eyes. — Pfhorrest

This is not in the least bit true. Virtually everyone in the world believes their eyes (especially if you take as I presume it was rhetorically meant to imply senses in general), only the insane don't. There's nowhere near this level of agreement that pain is bad.

Empiricism about the external world is indubitable because without it one would be unable to simply navigate 3D space. There was a good thread about this recently but I can't remember whose it was, but when you don't focus on the stuff we generally discuss (God, ghosts etc) we agree on the vast majority of stuff, and most of that agreement is about the qualities of what we sense (the other parts being things like the meaning of words and the rules of maths etc).

The relationship between pain and 'badness' does not enjoy anything like this level of agreement. The argument for empiricism is based on this indubitability. So no similar argument can be made for treating moral judgment as measured by hedonic variables.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum