-

Pfhorrest

4.6kMy general position on the nature of reality is empirical realism.

Pfhorrest

4.6kMy general position on the nature of reality is empirical realism.

That is to say, I hold that there definitely is an objective reality, as opposed to any kind of relativism, idealism, or nihilism, which hold either that what is real is relative to some group's beliefs or to someone's subjective experiences, or else (as I consider equivalent to those) that nothing is actually real at all.

But I also hold that the content of that reality is entirely empirical in nature, that there is nothing real that is in principle beyond all observation, that if something exists, there will be some noticeable difference in the reality that we experience compared to what we would experience if it did not exist, and the whole of that thing's existence is the observable differences in reality it makes.

This empirical realism might well also be called physicalist phenomenalism, in that it holds that only physical phenomena exist — which is to say, things that are observable (phenomena) in an objective (physical) way accessible to all observers and not mere figments of any one person's imagination. This kind of view traces back to at least John Stuart Mill, who held the "permanent possibilities of experience" to constitute the entirety of an object's existence.

This is a kind of monism, holding that there is one kind of stuff that exists that all the many things in reality are made up of, in contrast with pluralist ontologies that hold that there are multiple fundamentally different kinds of stuff, especially with dualism as espoused by the likes of Rene Descartes which holds that there are wholly different mental and physical kinds of stuff. It is not quite the usual monism held contrary to that dualism, namely materialism, though as described above it is definitely physicalist; nor is it quite the other usual kind of monism, idealism, though as described above it is definitely phenomenalist.

But neither is it quite neutral monism in the usual sense, as espoused by the likes of Baruch Spinoza, as that holds that there is one kind of stuff that has both mental and material properties; whereas I hold that there are not so much different kinds of properties, much less different kinds of stuff, as there are what could crudely be called mental and material ways of looking at the same properties and the same objects, that are essentially both mind-like and matter-like in different ways, that distinction no longer really properly applying when we really get down to the details.

I would say that the most concrete things that exist are, as Alfred North Whitehead called them, "occasions of experience". These are the things of which we have the most direct, unmediated awareness, and the only things of which we can have no doubt.

Rene Descartes famously attempted to systematically doubt everything he could, including the reliability of experiences of the world, and consequently of the existence of any physical things in particular; which he then took, I think a step too far, as doubting whether anything at all physical existed, but I will return to that in a moment. He found that the only thing he could not possibly doubt was the occurrence of his own doubting, and consequently, his own existence as some kind of thinking thing that is capable of doubting.

But other philosophers such as Pierre Gassendi and Georg Lichtenberg have in the years since argued, as I agree, that the existence of oneself is not strictly warranted by the kind of systemic doubt Descartes engaged in; instead, all that is truly indubitable is that thinking occurs, or at least, that some kind of cognitive or mental activity occurs. I prefer to use the word "thought" in a more narrow sense than merely any mental activity, so what I would say is all that survives such a Cartesian attempt at universal doubt is experience: one cannot doubt that an experience of doubt is being had, and so that some kind of experience is being had.

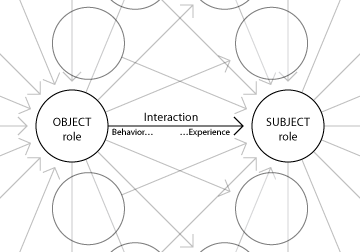

But I then say that the concept of an experience is inherently a relational one: someone has an experience of something. An experience being had by nobody is an experience not being had at all, and an experience being had of nothing is again an experience not being had at all. This indubitable experience thus immediately gives justification to the notion of both a self, which is whoever the someone having the experience is, and also a world, which is whatever the something being experienced is.

One may yet have no idea what the nature of oneself or the world is, in any detail at all, but one can no more doubt that oneself exists to have an experience than that experience is happening, and more still than that, one cannot doubt that something is being experienced, and whatever that something is, in its entirety, that is what one calls the world. So from the moment we are aware of any experience at all, we can conclude that there is some world or another being experienced, and we can then attend to the particulars of those experiences to suss out the particular nature of that world.

The particular occasions of experience are thus the most fundamentally concrete parts of the world, and everything else that we postulate the existence of, including things as elementary as matter, is some abstraction that's only real inasmuch as postulating its existence helps explain the particular occasions of experience that we have.

George Berkeley famously said that "to be is to be perceived", and I don't agree with that entirely, in part because I take perception to be a narrower concept than experience in a broader sense, and because I don't think it is the actual act of being experienced per se that constitutes something's existence, but rather the potential to be experienced. I would instead say not that to be is to be perceived, or that to be is to be experienced, but that to be is to be experienceable.

And I find this adage to combine in very interesting ways with two other famous philosophical adages: Socrates said that "to do is to be", meaning that anything that does something necessarily exists; and more poignantly, Jean-Paul Sartre said that "to be is to do", meaning that what something is is defined by what that something does. Being, existence, can be reduced to the potential for or habit of some set of behaviors: things are, or at least are defined by, what they do, or at least what they tend to do. (Coupled with the association of mass to substance and energy to causation, this notion that to be is to do seems to me a vague predecessor to the notion of mass-energy equivalence).

To combine this with my adaptation of Berkeley's adage, we get concepts like "to do is to be experienced", "to be experienced is to do", "to be done unto is to experience", and "to experience is to be done unto".

This paints experience and behavior as two sides of the same coin, opposite perspectives on the same one thing: an interaction. Our experience of a thing is that thing's behavior upon us. An object is red inasmuch as it appears red, and it appears red inasmuch as it emits light toward us in certain frequencies and not others: the emission of the right frequencies of light, a behavior in a very broad sense, constitutes the property of redness. Every other property of an object is likewise defined by what it does, perhaps in response to something that we must do first: an object's color may be relative to what frequencies of light we shine on it (e.g. something that is red under white light may be black under blue light), the shape of the object as felt by touch is defined by where it pushes back on our nerves when we press them into it, and many other more subtle properties of things discovered by experiments are defined by what that thing does when we do something to it.

We can thus define all objects by their function from their experiences to their behaviors: what they do in response to what it done to them. The specifics of that function, a mathematical concept mapping inputs to outputs, defines the abstract object that is held to be responsible for the concrete experiences we have. Every object's behavior upon other objects constitutes an aspect of those other objects' experience, and every object's experience is composed of the behaviors of the rest of the world upon it.

All of reality can then be seen as a web of these interactions, the interactions themselves being the most concrete constituents of that reality, with the vertices of that web constituting the more abstract objects, in the usual sense, of that reality.

We each find ourselves to be one complex object in that web, and the things we have the most direct, unmediated awareness of are those interactions between our own constituent parts, and between ourselves and the nearest other vertices in that web, those interactions constituting our experience of the world, and also our behavior upon the world. By identifying the patterns in those experiences, we can begin to build an idea of what the rest of the world beyond that is like, inferring the existence and function of other nodes beyond the ones we are directly connected to by their influence in the patterns of behavior of (and thus our experience of) those nearest nodes.

This work is where philosophy ends, as far as investigating reality goes at least, and the physical sciences take over, postulating the existence of abstract objects with functions that would give rise to the concrete experiences we have of the world. Early physics began by identifying the behavior of large complex objects, and the different kinds of stuff that they are made of, "elements" like "earth", "water", and "air". But in time it has found those all to be made of many kinds of smaller particles of a similar nature to each other, molecules, interacting with each other in different ways. Those many diverse molecules have in turn been found to all be composed of a more limited set of still smaller particles, atoms; and those in turn of an even smaller set of smaller particles still, electrons and nucleons like protons and neutrons; the latter in turn made up of triplets of two still smaller and more fundamental particles called up and down quarks.

And I believe that contemporary physics has come far enough along, dug deep enough into the constituent particles of reality, that it has now identified as its most fundamental particles objects that are literally identifiable with the very "occasions of experience" that make up the web of reality described in my ontology above.

For clearest illustration, consider the experience of vision, which is now understood to be mediated by particles of light called photons. Whenever we see anything, all we're actually seeing in the most technical sense is the photons that hit our eyes; the objects we see, in the casual sense most people mean, are only inferred from the patterns in those photons hitting our eyes. Because of the distortion of space and time relative to motion, from the frame of reference of any given photon, the distance that it travels between whatever emitted it and your eye is zero, and the journey takes no time at all; from the photon's perspective, it exists only at a point and only for an instant,the whole of its being constituted entirely by the interaction between whatever emitted it and your eye. Contemporary theories of physics hold that fundamentally, all of the most fundamental particles are essentially like photons in that way, all naturally moving at the speed of light, and so finding themselves, in their own frames of reference, to exist for but an instant at the point where two other objects interact, and their own existence consisting entirely of that interaction between them.

It is only the aggregate patterns of interactions between these particles that gives rise to the appearance of the conventional, slower-moving particles out of which all of the aforementioned structures arise, up to the macroscopic scale we're familiar with. For instance, electrons as we commonly understand them are understood to be an aggregate pattern of two different light-like particles, each similar to an electron and to each other but differing from each other in a property called spin, neither of which is able to travel any measurably large distance in space without immediately interacting with something called the Higgs field. The Higgs field absorbs that particle, and immediately emits another identical to it other than having opposite spin, only for that to be immediately reabsorbed and a particle like the first one emitted again, the overall pattern of those two kinds of particles, oscillating between each other immeasurably quickly as they interact with the Higgs field, constituting the particle that we conventionally think of as an electron.

Those light-like fundamental particles, that I think are identifiable with the interactions or "occasions of experience" that constitute the web of reality as described here in my ontology, thus make up, in a sense, the electrons and quarks that make up the atoms that make up the molecules that make up all of the matter that makes up the entire world, including people like you and me.

-

Kenosha Kid

3.2kBut I then say that the concept of an experience is inherently a relational one: someone has an experience of something. An experience being had by nobody is an experience not being had at all, and an experience being had of nothing is again an experience not being had at all. This indubitable experience thus immediately gives justification to the notion of both a self, which is whoever the someone having the experience is, and also a world, which is whatever the something being experienced is. — Pfhorrest

Kenosha Kid

3.2kBut I then say that the concept of an experience is inherently a relational one: someone has an experience of something. An experience being had by nobody is an experience not being had at all, and an experience being had of nothing is again an experience not being had at all. This indubitable experience thus immediately gives justification to the notion of both a self, which is whoever the someone having the experience is, and also a world, which is whatever the something being experienced is. — Pfhorrest

Does this resolve beyond the cogito? I can doubt whether I exist, which implies the existence of a subject (self) and an object (self) because they are one and the same. But doubting the world exists doesn't imply a world beyond the self, right? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kIt is possible that oneself is the world, sure; that self and world are the same thing. But then you just have solipsism, which is trivial: even if the world just is oneself, there is still a divide between the parts of it that one has direct knowledge and control over, and parts that are beyond ones knowledge and control. Even if that whole world-self is all there is, there is still the same practical reason to investigate into and act upon the parts of it that seem ‘other’ exactly as one would if it were in fact other. In the end, identifying the world with oneself is no different than identifying oneself as just a part of the world, which is uncontroversially true.

Pfhorrest

4.6kIt is possible that oneself is the world, sure; that self and world are the same thing. But then you just have solipsism, which is trivial: even if the world just is oneself, there is still a divide between the parts of it that one has direct knowledge and control over, and parts that are beyond ones knowledge and control. Even if that whole world-self is all there is, there is still the same practical reason to investigate into and act upon the parts of it that seem ‘other’ exactly as one would if it were in fact other. In the end, identifying the world with oneself is no different than identifying oneself as just a part of the world, which is uncontroversially true. -

Pantagruel

3.6kMy general position on the nature of reality is empirical realism. — Pfhorrest

Pantagruel

3.6kMy general position on the nature of reality is empirical realism. — Pfhorrest

If empirical realism is an ontological verus an epistemological stance, then how do you describe the status of subjective experiences, from an empirical realist standpoint? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI’m not completely sure I understand your question, but if this helps answer: it’s a kind of direct realism wherein subjective experiences are just small, incomplete, and possibly distorted views of reality itself (rather than either an infallible complete view of reality, or only some kind of representation of a reality that might be nothing like its representation).

Pfhorrest

4.6kI’m not completely sure I understand your question, but if this helps answer: it’s a kind of direct realism wherein subjective experiences are just small, incomplete, and possibly distorted views of reality itself (rather than either an infallible complete view of reality, or only some kind of representation of a reality that might be nothing like its representation). -

Pantagruel

3.6k

Pantagruel

3.6k

But if these are distinct categories, then would not the concept of "reality" by definition (and usage) have to be expanded to encompass both? Maybe it is an "inflationary" reality(-concept). ie. the representation has a reality also.representation of a reality that might be nothing like its representation — Pfhorrest -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI don’t know, you’d have to ask a representative realist how they account from that. I think their view doesn’t make sense, that’s why I disagree with it.

Pfhorrest

4.6kI don’t know, you’d have to ask a representative realist how they account from that. I think their view doesn’t make sense, that’s why I disagree with it.

I just thought of another way of relating subjective experiences to objective reality in my view. Subjective experience are like partial sums of an infinite series; objective reality is the total sum of that infinite series, which is the limit of the series of partial sums of it. -

Pantagruel

3.6kAs long as the subjective is accounted for. That's why I favour Scientific Realism. There is a strong bridge between the subjective (methodology) and the real. I have found that sociological theories of communicative action take it just that much bit further, to a constituted-constituting reality.

Pantagruel

3.6kAs long as the subjective is accounted for. That's why I favour Scientific Realism. There is a strong bridge between the subjective (methodology) and the real. I have found that sociological theories of communicative action take it just that much bit further, to a constituted-constituting reality.

Just had to ask. It's interesting how you invoked a mathematical concept as the bridge to subjectivity. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kI've read this a few times now and I'm still not sure I grasp the thesis. That is, I'm not sure which you think are the key points. The most peculiar part is the sense in which no time passes for, and no space is traversed by, light: a feature of SR that has always amazed and alarmed me. As you put it, the tick of any clock in a physical reference frame is due to the finite time between trajectories of the Higgs re-emiting particles. (We've discussed this before and as you know I'm not so sure we should take this literally, but I'll put that to one side.)

Kenosha Kid

3.2kI've read this a few times now and I'm still not sure I grasp the thesis. That is, I'm not sure which you think are the key points. The most peculiar part is the sense in which no time passes for, and no space is traversed by, light: a feature of SR that has always amazed and alarmed me. As you put it, the tick of any clock in a physical reference frame is due to the finite time between trajectories of the Higgs re-emiting particles. (We've discussed this before and as you know I'm not so sure we should take this literally, but I'll put that to one side.)

But I'm not clear how this all fits together for you. Is it that there's no effective separation between our seeing and the thing we see, except for a fluke of Higgs fields and reference frames? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe stuff about the Higgs etc is really an addendum to the overall thesis, though I do think it's one of the more interesting things in there.

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe stuff about the Higgs etc is really an addendum to the overall thesis, though I do think it's one of the more interesting things in there.

The overall thesis is that there is nothing to reality besides the observable features of it, nothing hidden behind our experience, of which our experience is merely a representation -- our experience is direct contact with a very small part of reality (the parts that we are literally in direct contact with: the photons hitting our eyes, and mediating the kinetic interaction between air molecules and our ears, or between anything else and our skin, as well as the chemical interactions with our olfactory sensors), and we (intuitively) infer the rest of reality from the behavior of that very small part, in exactly the same way that we can infer wind from the motion of leaves, or infer gravitational waves from the changing interference patterns of two carefully set-up lasers.

It's almost a kind of idealism, except that reality isn't "in" any mind(s), it's just made up of "mind-like stuff"; the actual (e.g. human) minds experiencing it being presumably just the activity of brains, those brains being made up of matter, which is made up of this "mind-like stuff", these "occasions of experience" as Whitehead called them.

It also ties into the mathematicism we were discussing in my other thread. Those "occasions of experience" are equally interpretable as behaviors of thing A upon thing B, as much as they are experiences by thing B of thing A; those are just two ways of looking at the interaction between things A and B. The things themselves in turn are just the bundles of their properties, which are all behaviors, or propensities to behave certain ways in response to certain things that are done unto them, i.e. in response to certain things they experience, i.e. certain other interactions. So every thing is entirely definable by its function from its experiences (inputs into it from its interactions) to its behaviors (outputs from it through its interactions). The interactions/experiences/behaviors are the edges of a complex graph, and the nodes of that graph, the things experiencing and behaving, interacting with each other, the functions mapping the stuff done to them to stuff that they do, are the objects of reality.

The stuff about the Higgs etc is just an interesting observation at the end of all of that, noting that a posteriori empirical science, which began by investigating big compound nodes in that graph (macroscopic objects) and has investigated over time into the smaller and smaller components, seems to have finally arrived a posteriori at components that can be taken as identical with the the very same constituents of reality that we've arrived at through a priori philosophizing here. Massless particles like photons (and the particles that get "blended" into electrons etc by the Higgs) are exactly like the "occasions of experience" that philosophers like Whitehead wrote about, and that in my elaboration upon that (viz the mathematicism stuff above) can be taken as signals passing between the mathematical functions that constitute the abstract object that is our concrete reality. -

Banno

30.6kThis empirical realism might well also be called physicalist phenomenalism, in that it holds that only physical phenomena exist — Pfhorrest

Banno

30.6kThis empirical realism might well also be called physicalist phenomenalism, in that it holds that only physical phenomena exist — Pfhorrest

...and hence the realism reduces to phenomenology.

Why? Because it joins Descartes in the error of following the chimera of certainty, finding oneself in a garden of mere experience and behaviour.

In the very act of setting out this fabulous journey you use, and hence must admit, the language in which it is embedded. Here's a certainty that escapes mere experience. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kIn the very act of setting out this fabulous journey you use, and hence must admit, the language in which it is embedded. Here's a certainty that escapes mere experience. — Banno

Pfhorrest

4.6kIn the very act of setting out this fabulous journey you use, and hence must admit, the language in which it is embedded. Here's a certainty that escapes mere experience. — Banno

How is language something beyond experience, or behavior? It’s something we do to each other, and experience each other doing — as well as something we do to ourselves, and experience ourselves doing. -

Banno

30.6kHow is language something beyond experience — Pfhorrest

Banno

30.6kHow is language something beyond experience — Pfhorrest

It isn't.

But it can't be done without someone else - which is why you are presenting your theses in a public forum.

So you can leave out the bit that deduces stuff from a basis of certainty, and proceed instead from the common sense of the stuff around us. Hence, there is no need to derive only from your own experience in order to justify your belief in chairs and tables and trees and people to talk to. That you are talking to us shows that you are embedded in a world where such things are ubiquitous. -

Banno

30.6kThat was my initial reaction, on reading the phrase empirical realism; there's a distinction between empirical method, a way of finding things out, and realism, a way in which things are; a too-easy slide between what we know and how things are, between epistemology and metaphysics. The same thing shows in the move from Quine's web of belief to a web of reality.

Banno

30.6kThat was my initial reaction, on reading the phrase empirical realism; there's a distinction between empirical method, a way of finding things out, and realism, a way in which things are; a too-easy slide between what we know and how things are, between epistemology and metaphysics. The same thing shows in the move from Quine's web of belief to a web of reality. -

Banno

30.6kThe theory looks to be realism in name only; for all that is supposedly knowable are those interactions that cause phenomena.

Banno

30.6kThe theory looks to be realism in name only; for all that is supposedly knowable are those interactions that cause phenomena.

That puts far to great a restriction on what is knowable; the philosopher's error of seeking certainty.

The antidote is the realisation that not just certainty, but also doubt, may need justification. -

Banno

30.6kIt's almost a kind of idealism, except that reality isn't "in" any mind(s), it's just made up of "mind-like stuff"; the actual (e.g. human) minds experiencing it being presumably just the activity of brains, those brains being made up of matter, which is made up of this "mind-like stuff", these "occasions of experience" as Whitehead called them. — Pfhorrest

Banno

30.6kIt's almost a kind of idealism, except that reality isn't "in" any mind(s), it's just made up of "mind-like stuff"; the actual (e.g. human) minds experiencing it being presumably just the activity of brains, those brains being made up of matter, which is made up of this "mind-like stuff", these "occasions of experience" as Whitehead called them. — Pfhorrest

I don't see how idealism is bypassed here. How can mind-like stuff be just the activity of brains, unless there are indeed brains? But there cannot be brains since all there is, is mind-like stuff, and brains are not mind-like stuff... a vicious little circle if ever there was one.

Pfhorrest is a covert idealist. -

Banno

30.6kThose light-like fundamental particles, that I think are identifiable with the interactions or "occasions of experience" that constitute the web of reality as described here in my ontology, thus make up, in a sense, the electrons and quarks that make up the atoms that make up the molecules that make up all of the matter that makes up the entire world, including people like you and me. — Pfhorrest

Banno

30.6kThose light-like fundamental particles, that I think are identifiable with the interactions or "occasions of experience" that constitute the web of reality as described here in my ontology, thus make up, in a sense, the electrons and quarks that make up the atoms that make up the molecules that make up all of the matter that makes up the entire world, including people like you and me. — Pfhorrest

Further evidence of covert idealism. Are they particles, and hence Pfhorrest is a realist, or are they "occasions of experience", and hence Pfhorrest is an idealist? This is the inevitable result of taking experience as fundamental, to the exclusion of all else. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe antidote is the realisation that not just certainty, but also doubt, requires justification. — Banno

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe antidote is the realisation that not just certainty, but also doubt, requires justification. — Banno

You seem to be arguing here for a critical rationalism, which I also support. But that's an epistemological position (which particular beliefs are justified), not an ontological position (what even is it for something to be real). The two are not in conflict, and are in fact necessitated by the same deeper principles.

Empiricism is necessitated by the same principle that necessitates rationalism more generally: every answer must be questionable, which means not taking anything on faith, which means not entertaining claims about anything that can't be tested.

Meanwhile objectivism is necessitated by the same principle that necessitates critical rationalism specifically: every question has an answer, which directly entails objectivism, but also demands a rejection of justificationism, as that leads via infinite regress to nihilism, leaving only the options of fideism, which we've already ruled out above, or else critical rationalism.

In any case, I'm not arguing for empirical realism from a place of Cartesian doubt. I haven't actually presented much of an argument here at all, merely an exploration of the relation of empirical realism to other threads of philosophical thought, including Spinoza (it's a neutral monism but not like his), Mill (it's much like his ontology), Descartes, Gassendi and Lichtenberg (it's not like Descartes because of the reasons Gassendi and Lichtenberg give), and Whitehead (it's very much like his ontology).

My argument for this position would just be an argument against nihilism (including solipsism, relativism, and subjectivism), and an argument against transcendentalism (meaning in this case basically supernaturalism), leaving us with the position that there are objective answers to questions about reality, but that those answers consist entirely of claims about the kinds of experiences there are available to be had in what circumstances.

How can mind-like stuff be just the activity of brains — Banno

"Mind-like stuff" is not the activity of brains, on my account. Actual minds are. "Mind-like stuff" is a loose way of saying essentially "information": it's the kind of stuff that minds process. Minds, being the behavior of brains, are made of that same stuff, because all physical stuff is. In a computer, every program is made of data, and what those programs act upon is more data. I'm saying reality is analogous to that, or maybe not even so distant as to be an analogy. Reality is made of information, of the kinds that minds process, but information that exists whether or not minds are there to be processing it; minds, being (behaviors of) real physical things like anything else, are made out of that same information, that they then process. The data is first, execution of the data comes later, and only certain data constructs do any interesting data-processing when executed; most just crash. (Which is why not all this information-stuff reality is made of exhibits consciousness like we normally think of it, despite being made of the same stuff as brains that can be conscious; it's not structured correctly, into a thinking machine. It's data that doesn't do anything interesting when executed).

Are they particles, and hence Pfhorrest is a realist, or are they "occasions of experience", and hence Pfhorrest is an idealist? — Banno

a vicious little circle if ever there was one — Banno

"Minds are an action of physical things, but physical stuff is made of ideas in minds"... sure, that's a primitive way I once thought of this line of thought decades ago, when I was tempted by both idealism in ontology class and materialism in philosophy of mind class.

The resolution to that apparent conflict is neutral monism. There isn't mental stuff and material stuff, or just one or the other, but a neutral stuff that's kinda both or neither. Physical stuff is phenomenal stuff, the kind of stuff you can empirically observe, but that isn't dependent on you observing it, that is independent of your particular subjective experience, without being something completely beyond all possibility of being experienced.

One direction away from that position lies supernaturalism, believing in stuff that can't possibly be observed, the existence of which could only be taken on faith, but "it's really objectively real I swear" if you do take it on faith. In the other direction away from it lies some kind of subjectivism, relativism, solipsism, or nihilism, denying that there is any reality to the stuff you experience beyond your experiencing of it, such that it would cease to exist if you did. Carefully avoiding anything like either of those leaves you where I am: empirical realism, or physicalist phenomenalism, or anti-supernaturalist anti-solipsism if you really prefer. -

Banno

30.6kEmpiricism is necessitated by the same principle that necessitates rationalism more generally: every answer must be questionable, which means not taking anything on faith, which means not entertaining claims about anything that can't be tested. — Pfhorrest

Banno

30.6kEmpiricism is necessitated by the same principle that necessitates rationalism more generally: every answer must be questionable, which means not taking anything on faith, which means not entertaining claims about anything that can't be tested. — Pfhorrest

Well, that ain't so. Think of Quine's holism. It's fine to question anything, but absurd to question everything.

There are things in which we needs must be confident in order to participate in doubt. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

You callin' me names?You seem to be arguing here for a critical rationalism... — Pfhorrest

Popper did say similar things, and I'm not in disagreement with much of what he wrote, but he was misled by certainty into thinking too highly of the issue of induction. No, I'm thinking Moore of Quine and Wittgenstein.

I don't see that disembodying ideas by calling them "information" relieves you of the charge of idealism. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThink of Quine's holism — Banno

Pfhorrest

4.6kThink of Quine's holism — Banno

I thought Quine's holism seemed obvious when I first heard about it, but then I was already a falsificationist by that time, and from a falsificationist viewpoint of course you're only ever testing the entirety of all your theoretical assumptions at once and can modify any of those assumptions you want to fit the new observation. Confirmation holism is only novel if you're already a confirmationist, which I'm not.

It's fine to question anything, but absurd to question everything. — Banno

I didn't say to question everything (at once). Like I said, I'm not coming from a place of Cartesian doubt; I only described the relationship of Descartes' thought (and later commentary on it) to mine.

You callin' me names? — Banno

If "critical rationalist" is a name, then it's a good one.

I don't see that disembodying ideas by calling them "information" relieves you of the charge of idealism. — Banno

The disembodiment is the whole crux there. If the "ideas" can exist without there being minds to be thinking them, as they can on my account, then they're not really "ideas" as usually meant by that word, so I don't use that word. -

Banno

30.6kBut gas is just more... I've lost track; is it real, or is it experience, or is it mere phenomena, or is it an idea, or is it information...?

Banno

30.6kBut gas is just more... I've lost track; is it real, or is it experience, or is it mere phenomena, or is it an idea, or is it information...? -

frank

18.9kBut I also hold that the content of that reality is entirely empirical in nature, that there is nothing real that is in principle beyond all observation, that if something exists, there will be some noticeable difference in the reality that we experience compared to what we would experience if it did not exist, and the whole of that thing's existence is the observable differences in reality it makes. — Pfhorrest

frank

18.9kBut I also hold that the content of that reality is entirely empirical in nature, that there is nothing real that is in principle beyond all observation, that if something exists, there will be some noticeable difference in the reality that we experience compared to what we would experience if it did not exist, and the whole of that thing's existence is the observable differences in reality it makes. — Pfhorrest

Isn't "empirical" a property of justifications or knowledge?

So you're saying there are no unstated true propositions? -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThe most peculiar part is the sense in which no time passes for, and no space is traversed by, light: a feature of SR that has always amazed and alarmed me. — Kenosha Kid

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThe most peculiar part is the sense in which no time passes for, and no space is traversed by, light: a feature of SR that has always amazed and alarmed me. — Kenosha Kid

Good reason to be skeptical.

So you can leave out the bit that deduces stuff from a basis of certainty, and proceed instead from the common sense of the stuff around us. — Banno

Yes, follow Banno's advice KK, use your common sense and be skeptical.

It's fine to question anything, but absurd to question everything.

There are things in which we needs must be confident in order to participate in doubt. — Banno

No it isn't absurd to question everything. That's how certainty is produced by questioning things. It's impractical to question everything, because this takes time, but the time it takes to question something, and resolve that doubt with a solution is not infinite. So the person who questions everything is slower (and much more annoying) than someone else, but that person is not incapacitated by such questioning.

There is no infinite regress of questioning unless you assume a relationship between one question and another. But if you question one thing, answer it and proceed, there is no infinite regress. In reality, this idea which you, and so many others profess, that a person "must be confident in order to participate in doubt", is what is absurd. It's just based in a straw man of what "doubt" is. Use your common sense, and recognize that certainty is only produced from questioning things, and therefore could not be necessary for it. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kGood reason to be skeptical. — Metaphysician Undercover

Kenosha Kid

3.2kGood reason to be skeptical. — Metaphysician Undercover

Let's put this in context: it's neither as amazing or alarming as a giant sky lord judging me for masturbating.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Does Art Reflect Reality? - The Real as Surreal in "Twin Peaks: The Return"

- Did the movie SIXTH SENSE destroy the myth that perception is absolute reality?

- Relationship between our perception of things and reality (and what is reality anyway?)

- Is an ontological fundamental [eg,God] really the greatest mystery in reality? Is reality ineffable?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum