-

Gregory

5kSo I wanted to sketch out some ideas on truth and reason (which are obviously very connected).

Gregory

5kSo I wanted to sketch out some ideas on truth and reason (which are obviously very connected).

For me, the whole point of Nietzsche's philosophy was that truth on earth (all he knew) was not clear and beautiful, but was instead dark, mysterious, decadent, and somewhat atonal. Truth is not like a beautiful goddess, but more like a grumpy, idiosyncratic trickster witch. For him, all the truths we can know are only partially true (although it's unavoidable that this claim itself would be absolute); and finally, for Nietzsche, truth is purely related to human psyche.

Then there is Thomism. Aquinas thought the desire of the intellect leads to the beatific vision, where it is more than satisfied. Truths are absolute, good, and beautiful. They are like pieces of God. Aquinas believed reason can lead to mysticism but is completed in it and is the foundation of those mystical experiences.

Now let me turn to Buddhism. Huston Smith writes: "Entering Zen is like stepping through Alice's looking glass. One finds oneself in a topsy-turvy wonderland where everything seems quite mad- charmingly mad for the most part, but mad all the same. It is a world of bewildering dialogues, obscure conundrums, stunning paradoxes, flagrant contradictions, and abrupt non sequiturs".

Thomas Aquinas thought it paramount to prove God's existence. Yet Buddha refused to answer the question, thinking it unnecessary and too connected to desire (tanha). Buddhism says people try to not desire thru desire itself, and so this is a vicious circle. They therefore break the structure of logic and shortcut reason to achieve an alternate state of mind in which everything is flux. In that state of mind even poetry becomes philosophy. Koan use cannot be over emphasized. They scatter the intellect and let Nirvana (or Satori) descend upon them and they see the world as the perfect playground of perfection. Again, Buddhist seem to go around reason and find trans-logical patterns for liberation. Buddha also wanted to change our very sensation of personhood, which would in turn alter our reason.

Catholics have condemned quietism as a "heresy" for its sayings that one must make no effort towards God through always being completely passive. Buddhism isn't quietest however. I thought their "right mindfulness" was a pure letting go, but their very next principle is "right concentration", which is deep action. Be that as it may, Thomas are truly afraid of altered states (a reason they are against drug use, but that that's another topic). John Paul II wrote that a Buddhist frees himself "from this world, necessitating a break with the ties that join us to external reality- ties existing in our human nature, in our psyche, in our bodies." Nevertheless, Buddhist say they achieve a state which seems identical to unity with the "One" spoken of by the Eleatics (Parmenides, Zeno, Melissus). Huston Smith again writes: "Edward Conze has compiled from Buddhist texts a series of attributes that apply to both (nirvana and an impersonal God). We are told 'that Nirvana is permanent, stable, imperishable, immovable, ageless, deathless, unborn, and unbecoming, that it is power, bliss and happiness, the secure refuge, the shelter, and the place of unassailable safety; that it is the real Truth and the supreme Reality; that it is the Good, the supreme goal and the one and only consummation of our life, the eternal, hidden and incomprehensible Peace.'" If you have read about the Greek Eleatics, you'll remember that they achieved just such a goal but via reason, the very tool that the Thomist use to reach a personal Truine God! The world is Maya for the Indian religions in the sense that our filters don't see reality as One. Maya is "magic" in that it tricks us. We mistake the world for many finite things instead of One divine Infinity. So reason seems to lead in many different directions and can be interpreted in various ways.

In conclusion, I would say it's unavoidable that we must use reason at least to a certain extent and in some way. We can't completely get rid of this faculty. But in starting out philosophy, I would like to know peoples' opinions about how to approach reason itself. What kind of a faculty is it? Is it mainly good? Is it mainly reliable? What are we to make of it? Thanks -

Pinprick

957I would like to know peoples' opinions about how to approach reason itself. What kind of a faculty is it? Is it mainly good? Is it mainly reliable? What are we to make of it? Thanks — Gregory

Pinprick

957I would like to know peoples' opinions about how to approach reason itself. What kind of a faculty is it? Is it mainly good? Is it mainly reliable? What are we to make of it? Thanks — Gregory

I like to look at reason through an evolutionary lens. Reason evolved, just like our intellect and other physical traits, because it is useful for survival and reproduction. Accordingly, it’s usefulness can really only extend to what we can sense. What I mean is, we lived for thousands of years only being able to interact with our immediate environment, because we had not yet developed scientific apparatuses to enhance our abilities. So reason necessarily evolved as a way to understand and predict our natural environment. As a result, there are likely aspects of nature that contradict reason, because they are aspects that we never truly encountered in our past (think quantum physics). However, I would posit that had we been able to experience the quantum world on a regular basis, reason would have evolved to look vastly different than it does now. -

Wayfarer

26.1kHave a read of God, Zen and the Intuition of Being. It's the book that first informed me about Jacques Maritain. (I had the paperback, it's now free online.)

Wayfarer

26.1kHave a read of God, Zen and the Intuition of Being. It's the book that first informed me about Jacques Maritain. (I had the paperback, it's now free online.)

Huston Smith on Zen - it says little about the reality of Zen Buddhism as practiced. It's considerably more prosaic and much more regimented in real life. Harold Stewart, an Australian poet and orientalist who lived in Kyoto for the last half of his life, said that in practice, the discipline of Zen is like joining the army! The paradoxes and koans are like distillations from centuries of experience. Sure they're baffling and paradoxical, but if you trace the origin and development of the tradition, they make their own kind of sense; they use reason to point beyond reason. In keeping with the old Eastern aphorism: that spiritual instruction is like a stick used to start the fire, when the fire is established, the stick is thrown into it. (Not something you'd likely hear from a Catholic :-) )

(Nevertheless, there's a healthy sub-culture today of Zen Catholicism which originated with Thomas Merton but now has many more teachers and centers, e.g. Ama Samy, Rueben Habito, Robert Kennedy, and others.)

As for reason - the roots of Western rationalism are much nearer to mysticism. The Parmenides was a mystical text par excellence, which is highly comparable to the contemporaneous texts of non-dualism in the ancient East. 'Reason' in the ancient Greek context was a cosmic philosophy, nothing like today's pragmatic scientific rationalism - it was concerned with reason on every level, the 'why' as well as the (merely) instrumental.

The traditional view in Western philosophy was that reason was higher than sense perception but not as high as noesis, intellectual conversion, or the vision of the Good. It was an heirearchy in which the higher forms of knowledge corresponded with the higher levels of truth (see Plato's Analogy of the Divided Line). Subsequently a good deal of the Platonist philosophy around these points became absorbed in the Christian theology via Christian Platonism but if you study the history of it (which is a deep study) you can still discern the Platonist origins. Jacques Maritain's book The Degrees of Knowledge is about this, but it's a formidable text (I've started it twice, didn't make a lot of headway with it.)

I would like to know peoples' opinions about how to approach reason itself. What kind of a faculty is it? Is it mainly good? Is it mainly reliable? What are we to make of it? Thanks — Gregory

I favor the Aristotelian view of rationality as being the distinctive hallmark of humanity. Again, I think there is 'wisdom beyond reason', but nowadays reason is generally deprecated as per this:

Reason evolved, just like our intellect and other physical traits, because it is useful for survival and reproduction. — Pinprick

As Leon Wieseltier pointed out in his review of Dennett's Breaking the Spell:

Dennett does not believe in reason. He will be outraged to hear this, since he regards himself as a giant of rationalism. But the reason he imputes to the human creatures depicted in his book is merely a creaturely reason. Dennett's natural history does not deny reason, it animalizes reason. It portrays reason in service to natural selection, and as a product of natural selection. But if reason is a product of natural selection, then how much confidence can we have in a rational argument for natural selection? The power of reason is owed to the independence of reason, and to nothing else. (In this respect, rationalism is closer to mysticism than it is to materialism.) Evolutionary biology cannot invoke the power of reason even as it destroys it.

——

(BTW you have a superfluous apostrophe in the title - what it literally spells out is ‘Reason and it is uses’ - it should be ‘its uses’. ) -

Mww

5.4kI would say it's unavoidable that we must use reason at least to a certain extent and in some way. — Gregory

Mww

5.4kI would say it's unavoidable that we must use reason at least to a certain extent and in some way. — Gregory

The conscious and otherwise rational human thinks constantly, and reason is thinking in accordance with rules. Except for pure reflex or sheer accident, reason is unavoidable. What we reason about changes over time; what we reason with, hasn’t changed noticeable since our attaining h. Sapiens evolutionary status.

What kind of a faculty is it? — Gregory

.....is fraught with circularities and inconsistencies, for it is a natural condition of humans to think according to rules, yet it can be none other than human reason which sets the rules to think in accordance with. The human doesn’t even know how his thinking comes about, he has no clue how his own brain operates with respect to his reason, or even that it does. He cannot use Nature as a definitive guide, for he must still think about what he gleans from Nature, again in accordance with the rules he himself constructs for his thinking, while he can, on the other hand, use Nature only to inform him if his self-constructed rules oppose each other. If they do, he must still use his thinking to construct new rules with respect to Nature, but constructing new rules is still thinking according to rules.

We find, then, after the dust of inquiry settles.....reason, not the faculty but rather, the method, is that which seeks for the unconditioned, the irreducible, in effect some semblance of certainty, and thereby that which minimizes the opportunities for rules to oppose each other. Reason the faculty then becomes that which grants that the rules are proper for the use to which they are directed.

Reason....the purely speculative method of rule construction and use.

Or not. Your rules may vary. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe capacity to reason evolved, plainly. But what of the 'furniture of reason' itself - the laws of logic, natural numbers, and so on? They did not come into being as a consequence of evolution. What came in to being was the capacity to understand them.

Wayfarer

26.1kThe capacity to reason evolved, plainly. But what of the 'furniture of reason' itself - the laws of logic, natural numbers, and so on? They did not come into being as a consequence of evolution. What came in to being was the capacity to understand them.

We find, then, after the dust of inquiry settles.....reason, not the faculty but rather, the method, is that which seeks for the unconditioned, the irreducible, in effect some semblance of certainty, and thereby that which minimizes the opportunities for rules to oppose each other. — Mww

Do you think there's much awareness of 'the unconditioned, the irreducible', in most current philosophical discourse? I read a lot more about the 'provisional nature of science'. The idea of 'the unconditioned' seems to me to have been dropped, on the whole. -

Ciceronianus

3.1kIs it mainly good? Is it mainly reliable? — Gregory

Ciceronianus

3.1kIs it mainly good? Is it mainly reliable? — Gregory

"Mainly" is good enough when it comes to reliability, and that reliability is the best we can do in any case when it comes to understanding the environment we're a part of and solving problems we face in interacting with the rest of the world; its primary function. As for the place of reason in ancient philosophy (as opposed to its place in Aquinas and others, where it's reduced to special pleading) it included what I call its primary function though limited by the science of the time, but the ancients were less hesitant than we are to apply it to determining moral conduct -

Olivier5

6.2kThe capacity to reason evolved, plainly. But what of the 'furniture of reason' itself - the laws of logic, natural numbers, and so on? They did not come into being as a consequence of evolution. What came in to being was the capacity to understand them. — Wayfarer

Olivier5

6.2kThe capacity to reason evolved, plainly. But what of the 'furniture of reason' itself - the laws of logic, natural numbers, and so on? They did not come into being as a consequence of evolution. What came in to being was the capacity to understand them. — Wayfarer

Yes, our capacity to hold on or assess logical inferences evolved, but unlike other things that evolved, it seems to touch on universals. For instance, Mathematics are universal. It’s not like some of us humans naturally think of space as having 7 dimensions for instance. We all have a 3D euclidian geometry ‘in mind’, when we drive or move around, or do geometry. And even when geometry tells us that nothing stops us from postulating a 7D space and from calculating motions within it, we still can’t imagine such a 7D space in our mind.

There are other cases of universals in evolution, that always have something mathematical about them: e.g. the DNA/RNA code, quasi universal body symmetry, or the use of folding to create 3D shapes from lines and filaments.

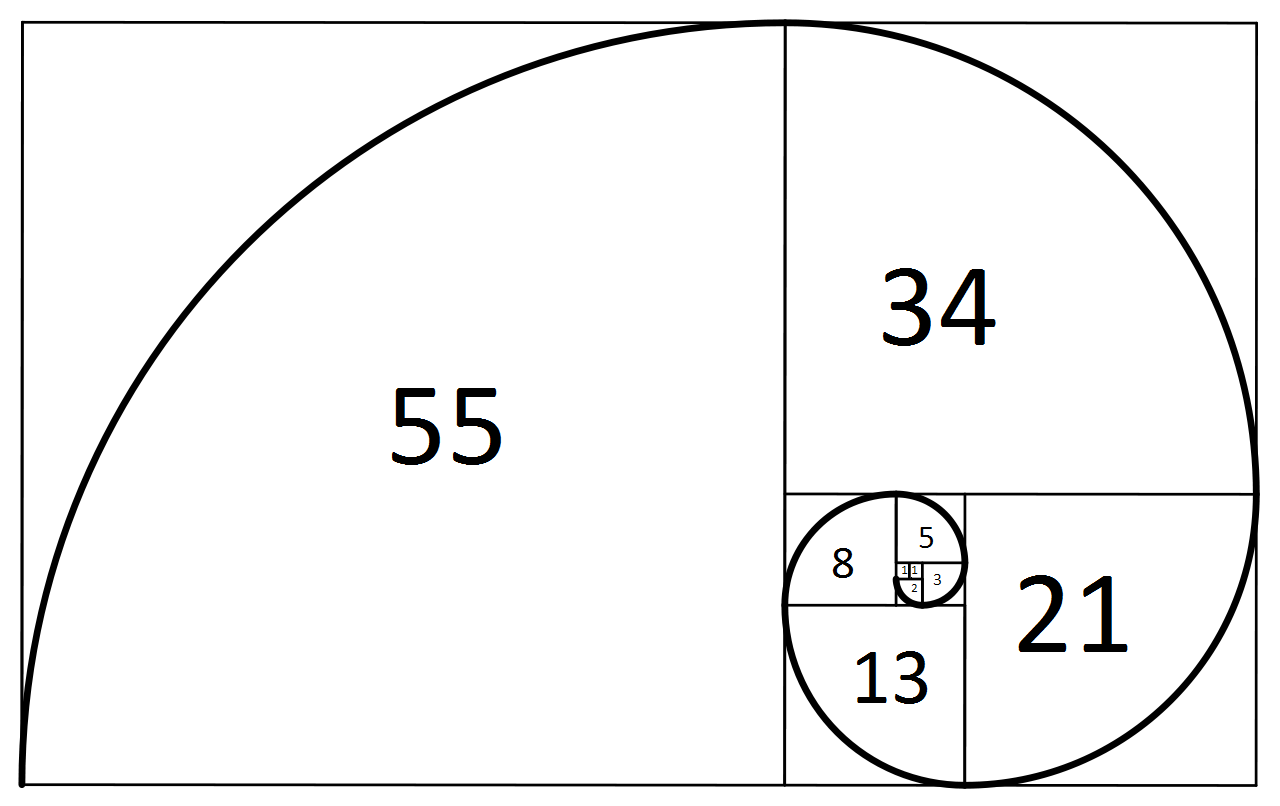

An example of this is helicoidal folding, ubiquitous in DNA, in proteins, or in large scale structures like snail shells, horns or flowers. In flowers and plants, the Fibonacci numbers and spiral seem to appear in countless structures (pine cones and the likes).

There seem to be some advantages to spirals. E.g. the shell of ammonites, and ammonites themselves could grow in size without changing their overall shape. It’s a very economical solution to the equation of growth.

Do you think there's much awareness of 'the unconditioned, the irreducible', in most current philosophical discourse? I read a lot more about the 'provisional nature of science'. The idea of 'the unconditioned' seems to me to have been dropped, on the whole. — Wayfarer

It’s still an ideal I think, an horizon, something we tend to even if we know we might never reach it. -

Wayfarer

26.1kWhere in nature is number or reason? — tim wood

Wayfarer

26.1kWhere in nature is number or reason? — tim wood

The question 'where?' indicates a spatio-temporal location. The nature of logical rules and numbers is such that they give order to thought itself, so they're part of the organisational structure of experience. But it's also a mistake to think they're 'in' the mind, as that is also misleadingly spatio-temporal i.e. 'in here' rather than 'out there'.

Actually there was a recent essay in the Smithsonian magazine, What is Math? But it likewise states that if math is to be considered real, then it must be 'out there'. I think that impulse to situate whatever is said to exist, is from what I would call the 'naturalist habit of thought'. This is to orient ourselves purely in respect of the horizontal dimension - self and other, subject and world. That orientation is a sort of 'master construct' within which questions are interpreted.

But logical laws are not anywhere - that is precisely the sense in which they transcend the temporal. They're kind of like the super-structure of reason. They're not any place, which is why they're universal.

the world itself works irrespective of the presence or absence of reason. — tim wood

It is often suggested nowadays that 'human reason' is a kind of fiction overlaid on an indifferent universe. But the reply to that is that humans have discovered rather a lot through the deployment of reason, specifically reason allied to mathematics, which is the basis of mathematical physics and many other areas of science. Mathematical reason is predictive, it enables us to discover things about the world that we otherwise wouldn't be able to know. Examples sorround all of us, not least the computers on which you and are writing and reading this text. So, how could reason be a contrivance or a convenient fiction? It seems to exert leverage over the world. Indeed, the discovery of leverage by Archimedes, a genius of the ancient world, was an early example of the power of reason, of which he was an exemplar.

(In classical philosophy, it was assumed that there was some kind of correspondence between Euclidean geometry and the divine order. I think that notion was more or less torpedoed by the advent of relativity and non-euclidean geometry. But it's a very difficult question involving mathematics that I can't say I understand. See discussion here.)

There are other cases of universals in evolution, that always have something mathematical about them: — Olivier5

Maybe are certain ways things have to be in order to exist. So, perhaps, as order appears, then it is incipiently mathematical, because there is repetition, and repitition is countable. Just thinking out loud. -

Mww

5.4kDo you think there's much awareness of 'the unconditioned, the irreducible', in most current philosophical discourse? — Wayfarer

Mww

5.4kDo you think there's much awareness of 'the unconditioned, the irreducible', in most current philosophical discourse? — Wayfarer

In philosophical discourse.....not that I know of. But then, I don’t hold a lot of respect for current philosophical discourse anyway, so the idea might be out there somewhere and I never bothered looking for it. Still, the notion is, using your term......archaic. Archaic adjacent, more like.

Everydayman is sort of aware of it, in principle, insofar as he invents a placeholder for the unconditioned, taking the form of transcendent entities of one kind or another. When he isn’t aware of it at all, but the principle still holds, is whenever he asks the why of a thing, followed by the why of whatever answer he just got, etc. Or when he wonders, what if.

I had in mind as irreducible, Aristotle’s logical laws, Kant’s categories, Rene’s sum. I’m sure you might have some irreducible concepts yourself. Be surprised if you didn't, assuming you grant the validity of the idea. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI had in mind as irreducible, Aristotle’s logical laws, Kant’s categories, Rene’s sum. — Mww

Wayfarer

26.1kI had in mind as irreducible, Aristotle’s logical laws, Kant’s categories, Rene’s sum. — Mww

I quite agree that they are examples of irreducibility. I think that this is what the atom came to signify - the atom being 'indivisible' and 'unchangeable' was able to represent 'the unconditioned' but still account for phenomena - hence the intuitive appeal of early atomism. The atom was a form of the unconditioned. I don't think it is tenable in light of modern physics however.

But I think the original concept of 'the unconditioned' is broader than that. '17th century philosophers held that reality comes in degrees—that some things that exist are more or less real than other things that exist. At least part of what dictates a being’s reality, according to these philosophers, is the extent to which its existence is dependent on other things: the less dependent a thing is on other things for its existence, the more real it is.' So the 'unconditioned' was the source of 'the conditioned' - this was the concept of To Hen, the One of Plotinus, which morphed over time into the 'Divine Intellect'.

Far as I know, numbers such as we humans understand them are simply those understandings of ours that we understand as such for our purposes.] — tim wood

I take it that any rational sentient being would discover at least some of the same mathematical principles that we have. That was the assumption behind the Pioneer Plaques and I think it's a sound assumption.

You might object that if they have no existence themselves, is there something, anything, underlying giving them ground out of which they emerge? I think not. Because to think in terms of any order, is to provide that order, and just that is ruled out. — tim wood

I don't say that numbers exist: I say that they are real, as constitutive elements of reason. But they're also not produced by our mind, because they are the same for any mind. Consider this passage from the Cambridge Companion to Aristotle:

1. Intelligible objects must be independent of particular minds because they are common to all who think. In coming to grasp them, an individual mind does not alter them in any way; it cannot convert them into its exclusive possessions or transform them into parts of itself. Moreover, the mind discovers them rather than forming or constructing them, and its grasp of them can be more or less adequate. Augustine concludes from these observations that intelligible objects cannot be part of reason's own nature or be produced by reason out of itself. They must exist independently of individual human minds.

More here.

Again, I understand that this type of Platonist reasoning is generally out of favour, but it seems intuitively sound to me. -

Mww

5.4kBut I think the original concept of 'the unconditioned' is broader than that. — Wayfarer

Mww

5.4kBut I think the original concept of 'the unconditioned' is broader than that. — Wayfarer

Agreed, atomism was the extent of empirical reducibility, the unconditioned having far broader extent than mere individual substance.

So the 'unconditioned' was the source of 'the conditioned' - this was the concept of To Hen, the One of Plotinus, which morphed over time into the 'Divine Intellect'. — Wayfarer

Yep.....just like that. The fundamental principle therein carried over undiminished into 18th century German continental idealism, which relocated the source of the principle while maintaining its authority. It was upon internalizing the subject, that human thought itself could assume the former domain of the external, at least in a logical sense, in that attributes could now be associated with it, just as attributes used to be given to material substances in the world. And attributes imply functionality....and we’re off to the epistemological rodeo.

—————-

”....Augustine concludes from these observations that intelligible objects cannot be part of reason's own nature or be produced by reason out of itself. They must exist independently of individual human minds....”

Again, I understand that this type of Platonist reasoning is generally out of favour, but it seems intuitively sound to me. — Wayfarer

Unless humans all operate under the auspices of the same rational methodology, in which case, all humans are naturally imbued with, if not the same intelligible objects, then at least the form to which intelligible objects must adhere. “2”, “II” and “द्वौ” are each intelligible objects subsumed under and representative of the unconditional “quantity”. Quantity has no representation of its own, no schemata by which it is necessarily conditioned, hence cannot be itself an intelligible object.

Woefully inadequate for the physicalists, the pure empiricists, rife with explanatory gaps as it may be, but they don’t have anything better, so......same as it ever was. -

Olivier5

6.2kMaybe are certain ways things have to be in order to exist. So, perhaps, as order appears, then it is incipiently mathematical, because there is repetition, and repitition is countable. Just thinking out loud. — Wayfarer

Olivier5

6.2kMaybe are certain ways things have to be in order to exist. So, perhaps, as order appears, then it is incipiently mathematical, because there is repetition, and repitition is countable. Just thinking out loud. — Wayfarer

Good intuition. I would only rephrase slightly: there are certain ways things have to be in order to EMERGE. Mathematics are heuristic. They describe how things emerge. Take a set of axioms, and you can develop a world from it, heuristically. Life does something quite similar, with gametes and seeds, and Darwin tells us it evolved heuristically over the eons. So the life forms that emerged throughout evolution took certain shapes because those shapes were ECONOMICAL in terms of emergence (emergence of new forms being rare and difficult, the forms that emerge are the easiest ones to ‘build’) and therefore those forms have a LOGIC of emergence, a certain way of building things up than COULD and DID happen. François Jacob wrote about that.

Now, here is an example of how a simple biological process of reproduction generates the Fibonacci sequence:

From this simplified example, one can see how any population emerging from an initial couple would (at least theoretically) follow the mathematical Fibonacci sequence. And plants and animals are populations of cells. So it s logical to assume they recycle the same processes of growth than populations do.

Here is something else the Fibonacci sequence can be used for:

-

Gregory

5kThanks for all the posts everyone. This is a good discussion. Last night I was reading articles off the internet comparing Nagarjuna and Zeno of Elea. One writer posited that they weren't simply arguing that the world and identity were illusion (and that we were the One) but that their paradoxes functioned as koans back in the day. Trying to reconcile finitude with infinity (Zeno) surely could be mind expanding! But what if we do merge with the One (or rather, wake up to it) and find that everything we thought was true (math, ect) has really been wrong and the real truth is the opposite of all we were once so sure of? It makes you wonder what reason can demonstrate in the Aristotelian sense.

Gregory

5kThanks for all the posts everyone. This is a good discussion. Last night I was reading articles off the internet comparing Nagarjuna and Zeno of Elea. One writer posited that they weren't simply arguing that the world and identity were illusion (and that we were the One) but that their paradoxes functioned as koans back in the day. Trying to reconcile finitude with infinity (Zeno) surely could be mind expanding! But what if we do merge with the One (or rather, wake up to it) and find that everything we thought was true (math, ect) has really been wrong and the real truth is the opposite of all we were once so sure of? It makes you wonder what reason can demonstrate in the Aristotelian sense.

I also wanted to add that Busdhists' anatta (atta is Pali for atman, which is Sanskrit) may be consistent with Hinduism. Hindus say your identity is the ocean of Brahmam. Buddhist say you have no soul and are usually silent about the emptiness you experience after enlightenment. So perhaps Buddhists are saying to Hindus "You mistake the soul for Brahmam. You are not there yet" and the Hindus respond "You say every thing is empty, but this is simply the impossibility of language to describe Brahmam. Someday you will see." Just a thought. Have a good day -

Wayfarer

26.1kSo the life forms that emerged throughout evolution took certain shapes because those shapes were ECONOMICAL in terms of emergence — Olivier5

Wayfarer

26.1kSo the life forms that emerged throughout evolution took certain shapes because those shapes were ECONOMICAL in terms of emergence — Olivier5

Yes. There is much discussion of that idea on this forum. I've learned a lot from Apokrisis about those kinds of ideas.

“2”, “II” and “द्वौ” are each intelligible objects subsumed under and representative of the unconditional “quantity”. — Mww

To be pedantic, they're symbols. What they signify is a number, that is what takes numerical intelligence to grasp.

what if we do merge with the One (or rather, wake up to it) and find that everything we thought was true (math, ect) has really been wrong and the real truth is the opposite of all we were once so sure of? It makes you wonder what reason can demonstrate in the Aristotelian sense. — Gregory

There is 'that which surpasses reason' - Buddhism explicitly refers to it. The Buddha says, in many canonical texts, that the dharma he teaches 'surpasses mere logic'. But that doesn't nullify logic.

I think you can say that, according to Buddhism, people cling to, are attached to their sense of what is real, which is built around what they can see, touch, feel, through the 'sense-gates', their likes, disllikes. and habits, and so on. In both Buddhist and Greek philosophy, the teaching is to see through that. It doesn't contradict logic, but it involves something deeper than logic, namely, in the Greek idiom, 'meta-noia' (in Buddhist texts parravritti) which is a 'turning around' of the mind's eye, so as to become aware of its own functioning.

Again, this is why the idea of an heirarchy of knowledge makes sense - there's sensory knowledge (posteriori), logical and rational truths (a priori) mathematical and geometric knowledge (dianoia). Mathematical knowledge is 'higher' than 'mere sensory' knowledge because it gives, in the hackneyed phrase, mathematical certainty. But it's still not the highest form of knowledge. That is what Maritain's Degrees of Knowledge is about (although I'd like to find a source which is less explicitly religious about it.)

I also wanted to add that Buddhists' anatta (atta is Pali for atman, which is Sanskrit) may be consistent with Hinduism. — Gregory

Don't say that to a Buddhist unless you want a major argument. :rage: -

Gregory

5k

Gregory

5k

From what I've gathered from Heidegger's lectures on what is metaphysics, if you were to turn the mind's eye around you would touch "the nothing". He says that "nothing" is not what is left when you negate "the all" but it is nothing that does that negating. In the West we have an assumption that truth has substance and nothingness is ugly. But what would happen if you negated nothingness? Would you get phenomena?

Maybe we actually form logic from our experience of the world. If we had always looked through different lenses like that great scene in 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, logic would be bewildering different from what we know now. Who knows? -

Wayfarer

26.1kI'm meaning to study Heidegger's take on metaphysics. As I understand it, he says that metaphysics since Plato has been systematically misleading culminating in the various crises of Western thought.

Wayfarer

26.1kI'm meaning to study Heidegger's take on metaphysics. As I understand it, he says that metaphysics since Plato has been systematically misleading culminating in the various crises of Western thought.

What I meant by 'metanoia' is more traditional - as per the definition: 'Metanoia means after-thought or beyond-thought, with meta meaning "after" or "beyond" (as in the modern word "metaphysics") and nous meaning "mind" (as in the modern world "paranoia"). It's commonly understood as "a transformative change of heart; especially: a spiritual conversion." The term suggests repudiation, change of mind, repentance, and atonement; but "conversion" and "reformation" may best approximate its connotation.'

Plus I was getting at the idea that what is 'beyond reason' as not merely negating reason, but surpassing reason. There's a difference between transcending reason and merely being irrational. The latter is considerably more common.

Maybe we actually form logic from our experience of the world. — Gregory

Empiricists say that, because, they say, the mind is a blank slate. But, as Kant pointed out, there must be some faculties of reason to be able to make sense of experience. -

Gregory

5k

Gregory

5k

Kant did think that Euclidean geometry was written into our minds a priori, but does this make this geometry true? Heidegger in his lecture on What is Metaphysics says that Hegel was right all along in asserting that pure being and pure nothing were identical. We reach out into the nothing, where there is no structure, by being Dasein. Nishida Kitaro wrote something similar in the Zen tradition in Japan. "Do not be seized by the sacred" he said, for many people make gods for themselves

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum