-

Pfhorrest

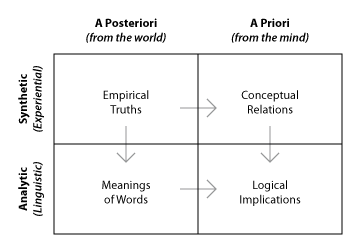

4.6kIn most of my previous threads about epistemology, I have been implicitly talking about a certain subset of knowledge that philosophers call "synthetic a posteriori", though most of what I've said applies also to the other kinds I am about to discuss as well. Synthetic a posteriori knowledge is the intersection of two distinctions that philosophers often make between different kinds of knowledge: the distinction between synthetic and analytic knowledge, and the distinction between a posteriori and a priori knowledge.

Pfhorrest

4.6kIn most of my previous threads about epistemology, I have been implicitly talking about a certain subset of knowledge that philosophers call "synthetic a posteriori", though most of what I've said applies also to the other kinds I am about to discuss as well. Synthetic a posteriori knowledge is the intersection of two distinctions that philosophers often make between different kinds of knowledge: the distinction between synthetic and analytic knowledge, and the distinction between a posteriori and a priori knowledge.

Analytic knowledge is knowledge about words or other abstract symbols and their meanings, independent of any investigation of the concrete world of experience. The classic example is the knowledge that all bachelors are unmarried, which depends only on knowing that the definition of a bachelor involves being unmarried, and so can be known just from that relationship between the words, even if you don't know what a bachelor is or what marriage is besides that marriage, whatever that means, is something bachelors, whatever those are, by definition haven't done. Synthetic knowledge, on the other hand, is knowledge about things besides just the meaning of words.

Similarly, a priori knowledge is knowledge that can be had before any experience of the world, knowledge that depends only on understanding concepts and their relationships to each other. Classical examples of a priori knowledge are mathematical facts, especially geometric ones, such as that the sum of the squares of the legs of a right triangle is equal to the square of that triangle's hypotenuse, which can be deduced just from thinking about imaginary triangles and squares and how they could or couldn't conceivably relate to each other, with no examination of actual triangular or square objects required. A posteriori knowledge, on the other hand, is knowledge that can only be had from some kind of experience of the world.

For much of the history of philosophy, these distinctions were considered synonymous, with all and only analytic knowledge, about the meaning of words, being held to be obtainable a priori, without any investigation of the world; and conversely, all and only synthetic knowledge, about things besides the meaning of words, being held to be obtainable a posteriori, via an investigation of the outside world, not just armchair thought experiments. But Immanuel Kant argued, as I agree, that these distinctions are orthogonal to each other, and that there is such a thing as synthetic a priori knowledge, into which category he held knowledge of mathematics and much of what was considered metaphysics to fall.

For example, in the geometric example given above of a priori knowledge about triangles and squares, there is no dependency on the meaning of the words "triangle" or "square", or any definition of one word in terms of the other; one need only be able to imagine the things that those words happen to refer to, without needing any words for them at all, to work out that certain relationship between them are necessary, certain, could not possibly be otherwise. (Although it is conversely possible to define triangles and squares in terms of more primitive mathematical objects in such a way that that relationship between them is logically entailed by their definitions alone, without needing to understand the synthetic meaning of any of the words in terms of imaginable geometric shapes).

I am not aware of Kant or other philosophers discussing the implication of an analytic a posteriori kind of knowledge by that name, but in Naming And Necessity Saul Kripke addresses at least very similar topics (such as how the fact that two names refer to the same thing, and so that the things they refer to are necessarily identical, is only known a posteriori). And I hold examining such a category is necessary for a complete understanding of knowledge.

For while synthetic a priori truths are necessary truths (as necessity tracks with a priority, and contingency with a posteriority), for that same reason of them being internal to the mind (hence a priori), but not in terms of publicly established relationships of words (hence synthetic), they are not interpersonally relatable, and so are only a matter of private knowledge, not public discourse. The only necessities that can be treated publicly are those phrased in terms of words with assigned meaning, analytic a priori truths; but those in turn depend on the analytic a posteriori (and thus contingent) assignment of such meaning.

Like many empiricist philosophers, such as David Hume, I hold that synthetic a posteriori knowledge is in a sense the primary kind of knowledge, both in that it is the kind that we are most concerned about in trying to understand what concrete reality is like, and in that it is where we get the basic ideas that we can then extrapolate further ideas from in our imaginations. It is those ideas in our imaginations, both of things we have directly experienced in the world and of new things we have constructed in our imaginations from the recombined parts and continued patterns of those things that we have directly experienced, that become the basis of synthetic a priori knowledge.

Though synthetic a posteriori knowledge is the kind of greatest concern, being about the concrete world we live in, it is only when we get to a priori knowledge that we can have our greatest certainty, for while all a posteriori knowledge is contingent, which is why we can only know it after investigating the world, all a priori knowledge is necessary, because it simply could not make any sense for things to be otherwise, there is no possible experience of the world that could contradict something that is a priori true.

When we then apply words to the ideas in our imaginations, we get analytic a priori knowledge, where we no longer need to actually do the imagining and can just manipulate abstract, symbolic representations of things without even needing to know exactly what they are representative of. This is where we enter the realm of logical truths, things that are true just by definition. But this kind of knowledge in turn depends on another kind of a posteriori knowledge, just as synthetic a priori knowledge depends on synthetic a posteriori knowledge to form the ideas that it manipulates in the imagination.

Analytic a priori knowledge, knowledge about what is or isn't true by definition, depends on knowing what the definitions of the words in question are, and that is not something that is itself known a priori, but only a posteriori. Words themselves do not inherently mean anything, but rather, linguistic communities arbitrarily assign meaning to words, and could assign them differently.

Initially, all words mean anything, and in doing so effectively mean nothing; it is the division of the world into those things the word means and those it doesn't that constitutes the assignment of meaning to it. Words mean what people mean them to mean, and so long as everyone involved agrees on the meaning of words, that is all that is necessary to know the truth of their meaning, the analytic a posteriori facts of what the words mean.

But when people disagree about what words rightly mean, we must have some method of deciding who is correct, if we are to salvage the possibility of any analytic knowledge at all; for if, for example, one person in a discourse insists that to be a bachelor only means to live a carefree life of alcohol, sex, and music (a la the Greek god Bacchus from whose name the term is derived), with no implications on marital status, while another person insists that to be a bachelor only means to be a human male of marriageable age who is nevertheless not married, with no implications on lifestyle besides that, then they will find no agreement on whether or not it is analytically, a priori, necessarily true that all bachelors are unmarried.

Such a conflict could be resolved in a creative and cooperative way by the use of qualifying terms to specify which sense of the word is meant: for example, the aforementioned disagreement might be resolved by the creation of the terms "lifestyle-bachelor" and "marriage-bachelor" to differentiate the two senses of the word "bachelor" in use. Or the same word can have multiple meanings, so long as the uses of the word in those multiple meanings do not conflict in context.

But if no such cooperative resolution is to be found, and an answer must be found as to which party to the conflict actually has the correct definition of the word in question, I propose that that answer be found by looking back through the history of the word's usage until the most recent uncontested usage can be found: the most recent definition of the word that was accepted by the entire linguistic community. That is then to be held as the correct definition of the word, the analytic a posteriori fact of its meaning, in much the same way that observations common to the experience of all observers constitute the synthetic a posteriori facts of the concrete world. -

bongo fury

1.8k

bongo fury

1.8k -

Pfhorrest

4.6kLike if "Superman" and "Clark Kent" are just two names for the same person, then everything that is true of Superman is necessarily also true of Clark Kent, because there's only one person in question.

Pfhorrest

4.6kLike if "Superman" and "Clark Kent" are just two names for the same person, then everything that is true of Superman is necessarily also true of Clark Kent, because there's only one person in question.

Or in Kripke's paradigmatic example, that "water" and "H2O" are two names for the same substance. Everything that's true of water is also true of H2O, because there's not two kinds of stuff, just two names for one kind of stuff. -

bongo fury

1.8k

bongo fury

1.8k

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Sensory Experience, Rational Knowledge and Contemplation: Are There Category Errors of Knowledge?

- The body of analytic knowledge cannot be incomplete in the Gödel sense

- For Kant, does the thing-in-itself represent the limit or the boundary of human knowledge?

- Is a Life Worth Living Dependent on the Knowledge Thereof?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum