-

Pfhorrest

4.6k(It's oddly appropriate that I can't decide what category of the forum to file this under.)

Pfhorrest

4.6k(It's oddly appropriate that I can't decide what category of the forum to file this under.)

It seems to me that there is a missing, as in unrecognized, sub-field of philosophy, that is spread piecemeal here and there in other fields including epistemology, the philosophy of education, the philosophy of science, and the philosophy of religion, but has not heretofore been studied as a subject unto itself, though it seems seems like it should be. I would want to call this field "academic philosophy", but not in the sense of "philosophy as practiced in academia", but rather "the philosophy of academia", as in, the analogue to "political philosophy", which is not "philosophy as practiced in politics" but rather "the philosophy of politics". Where that field is concerned with governance and the social institutions of justice, especially as they relate to the prescriptive authorities called states, this field as I would characterize it is concerned with education and the social institutions of knowledge, especially as they relate to the descriptive authorities that I would broadly characterize as religions.

In addition to that analogy between religions and states, I see these aspects as analogous as well:

Education (a social institute of epistemic guidance, not necessarily authoritarian)

is analogous to

Governance (a social institute of deontic guidance, not necessarily authoritarian)

Freethought (opposition to epistemic or descriptive authority)

is analogous to

Anarchism (opposition to deontic or prescriptive authority)

Freethinking or irreligious education

is therefore analogous to

Stateless or anarchic governance

Research (the process of coming up with what educators are to teach)

is analogous to

Legislation (the process of coming up with what governors are to enforce)

Teaching (epistemic "corrections", making sure people think right things not wrong ones)

is analogous to

Enforcement (deontic "corrections", making sure people do right things not wrong ones)

Testing (epistemic judgement)

is analogous to

Adjudication (deontic judgement)

A separation of research, teaching, and testing branches of education

is therefore analogous to

A separation of legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government

And lastly...

Proselytism (in the sense of widely distributing information, not necessarily with authoritative force)

is analogous to

Socialism (in the sense of widely distributing resources, not necessarily with authoritative force)

I do think there's a lot that can be taken away for the purposes of political philosophy from these analogues, but also and more to the point of this thread, it just seems strange to me that there isn't one unified field of philosophy that discusses epistemic authority and its justification, opposition, structure, etc, in the way that political philosophy discusses deontic authority and its justification, opposition, structure, etc.

I plan to do a couple of threads on these subtopics soon, but for this one I just wanted to call attention to this strange quirk in the way the study of philosophy is organized. -

jgill

4kA separation of research, teaching, and testing branches of education

jgill

4kA separation of research, teaching, and testing branches of education

is therefore analogous to a separation of legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government — Pfhorrest

Questionable analogy. In academia one person may have responsibilities in all three, in fact usually does. Not so in government. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kIt's not always been the case that government was separated into those three branches, but it's argued that there are good reasons why they should. I'm not saying that people in academia usually are separated along those lines, but that there may be analogous reasons that they should be: that one person should not both write the textbook, and teach from it, and test the students on whether they know their stuff. But, arguing for or against that is going to be a topic of one of those later threads I mentioned.

Pfhorrest

4.6kIt's not always been the case that government was separated into those three branches, but it's argued that there are good reasons why they should. I'm not saying that people in academia usually are separated along those lines, but that there may be analogous reasons that they should be: that one person should not both write the textbook, and teach from it, and test the students on whether they know their stuff. But, arguing for or against that is going to be a topic of one of those later threads I mentioned. -

jgill

4k. . . that one person should not both write the textbook, and teach from it, and test the students on whether they know their stuff. But, arguing for or against that is going to be a topic of one of those later threads — Pfhorrest

jgill

4k. . . that one person should not both write the textbook, and teach from it, and test the students on whether they know their stuff. But, arguing for or against that is going to be a topic of one of those later threads — Pfhorrest

Depends on that person. Is it a good text? Does the prof profit from its sale to his students? Is the prof fair? Not an easy yes or no here. But carry on. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kY'know maybe rather than starting new threads for each subtopic, I'll just do a series of posts in this thread.

Pfhorrest

4.6kY'know maybe rather than starting new threads for each subtopic, I'll just do a series of posts in this thread.

As should already be clear from my earlier thread on epistemology, I am broadly against the validity of any supposed epistemic authority, and so against the epistemic legitimacy of any religion, where that term is understood to mean some institute that claims such authority. This position is generally called freethought. But such freethought does not mean that I am against all or necessarily any of the descriptive claims issued forth by such institutions, only that I am against them being taken as authoritative simply for being issued by such institutions.

Just because I am against any such institution being taken as epistemically authoritative does not mean that I am against all social institutions seeking to promote knowledge. I am very much in favor of a widespread, global collaborative process of many individuals sharing their insights into the nature of reality, checking each other's findings, and collating the resulting consensus together into the closest thing to an authoritative understanding of reality that it is possible to create, for the reference of others who have not undertaken such exhaustive research themselves.

The proviso is simply that that resulting product should always be understood to be a work in progress, always open to question and revision, though it should in time become more and more hardened such that questions to which it does not already have answers become more and more difficult to find, and so large revisions to it become more and more difficult to make. This is essentially the process of peer review already widely in use in contemporary academia, and I don't claim to be putting forth much if anything new here in that regard, merely documenting the structure of a process of which I approve, for completeness of my philosophy.

The process proceeds in three broad phases:

- In the first phase, in what are called primary sources of knowledge, researchers publish detailed accounts of the observations that they have made, including especially the circumstances under which they were made, such as the setup of an experiment if a controlled experiment was done, or other important contextual information if an observation was made in the field, so that others can later attempt to replicate those circumstances and see if they observe the same phenomena; and these primary sources can also share the conclusions their authors draw from their observations.

- In the second phase, in what are called secondary sources, groups of other researchers review and comment on the quality of that original research in media such as journals, republishing the original research that they find worthy in the process.

- In the third phase, still others gauge the consensus opinion held between those secondary sources on what can somewhat reliably, though of course always still tentatively, be said about what is real, and publish those conclusions in more accessible summary works called tertiary sources, such as textbooks and encyclopedias.

(@jgill I gather you work in academia yourself so maybe you can check this for accuracy.)

These reference works are thus the closest things to epistemically authoritative texts that are possible, the reasonable substitute for authoritative religious texts traditionally taken as infallible fonts of knowledge; though these tertiary sources are not to be taken so infallibly, but understood as merely the best findings about reality that are as yet available, the theories that have survived not only the empirical testing of some individual researcher, but also the heavy criticism of everyone else participating in this endeavor throughout the world. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI guess I'll just continue the series then:

Pfhorrest

4.6kI guess I'll just continue the series then:

Aside from that multi-tiered process of research just described to produce an alternative to traditional holy texts, an entirely different but valuable social role that religious education has but secular education largely seems to be lacking is that of what we might call the "pastor". Apart from its religious meaning, that is a Latin word roughly equivalent to the English word "shepherd", with etymological roots relating to nourishing and protecting. So by that word in this context I mean a generally smart and knowledgeable person who is well-versed in the "authoritative" texts – a religion's holy book in the traditional role, but the tertiary reference books described above in the secularized version – to whom laypeople can come if they have individual questions about what is real, or to whom parties in a dispute about that can come for mediation and adjudication.

The answers given by such a person should not to be taken on their own personal authority, but on the "authority", such as it is, of the entire global process leading to the production of the reference works to which the pastor refers for their answers. Such pastors should be free to choose the reference works that they find best to use in this process, and individuals or disputing parties coming to them for answers or mediation should be free to choose pastors that they find best to use for their purposes, including for the reason of their choice of reference works. Furthermore, the reference works should not be taken by the pastors as infallible, and in each case it should be possible in principle – though increasingly more difficult in practice over time – to successfully challenge the claims of the reference works, and in doing so force a revision to them.

In this way the entire process remains technically non-authoritative, with lay people merely choosing to invest those who they judge to be smarter and more knowledgeable than themselves with a transient semblance of authority to help them better figure out what to think for themselves, or to settle arguments that they cannot settle between themselves.

(How to resolve cases where different parties to the same dispute appeal to different pastors for mediation will be addressed later.) -

jgill

4kI pretty much agree with everything you have said. I don't see anything novel in what you have written, but you have explained it well. Having worked in academia, however, I have rarely witnessed this degree of perfection. Take reviewing, for instance. I once wrote a paper and stated a simple example in the first or second paragraph demonstrating why a certain result obtained in another paper under slightly different hypotheses could not occur. The reviewer said the paper should be accepted but that the result from the other paper would ensue. I wrote back explaining why that result would not follow. Never heard back, but the paper was quickly published as I had written it. When a reviewer knows and presumably respects the work of an author they may skim over a few details. But this is math, and not biology.

jgill

4kI pretty much agree with everything you have said. I don't see anything novel in what you have written, but you have explained it well. Having worked in academia, however, I have rarely witnessed this degree of perfection. Take reviewing, for instance. I once wrote a paper and stated a simple example in the first or second paragraph demonstrating why a certain result obtained in another paper under slightly different hypotheses could not occur. The reviewer said the paper should be accepted but that the result from the other paper would ensue. I wrote back explaining why that result would not follow. Never heard back, but the paper was quickly published as I had written it. When a reviewer knows and presumably respects the work of an author they may skim over a few details. But this is math, and not biology.

At every stage of the process you have described things can go haywire. However, when the work has important consequences things go more according to your doctrine. -

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Jack Cummins

5.7k

I can see that your approach is one which tries to see the importance of all views rather than any one, but the problem which I see is that it places too much power in the hands of the academic elite. I am pointing here your suggestions on religious knowledge based on a process of peer review as being a 'substitute for authoritative religious texts'. Forgive me if I misunderstand you, but your use of the word pastor, which comes from the religious context, seems to be reinterpreted to make the academic, such as the professors, into a new form of pastors, and of priestly significance.

Peer review may work in the academic world, and I am sure that there is an elite academic world of philosophy, but to have decisions as to what is true, especially in the realms of religion, being decided as you describe seems completely hierarchical and can be seen as giving too much power to the academic elite. This raises questions, including the socioeconomic issues underlying who become the academic elite, and the processes of election and inclusion in this power process.

Even though you say the system would not be authoritarian in telling people what to believe it does still seem that the process would be giving be giving those ranking in the academic establishments a certain monopoly on the whole viewing of knowledge. Even though you suggest that it would include other people's ideas it does seem like a system which would reinforce the power of the academic hierarchy to have the ultimate word in how and on what basis ideas are and should be evaluated. I would imagine that this happens to some extent already but it just seems that you wish to make academia even more powerful, as judges in determining 'the best findings about reality.' -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI'm not suggesting that anything be done differently with regard to academia than is done today, but just outlining the ideals of the modern academic process -- which @jgill confirms are mostly accurate (thanks, and yeah, I acknowledge that in practice we often fail to live up to these ideals) -- and contrasting this with the religious model of unquestionable truth handed down from on high... but also with the complete abandonment of any structured pursuit of truth, for reasons I'll go into soon.

Pfhorrest

4.6kI'm not suggesting that anything be done differently with regard to academia than is done today, but just outlining the ideals of the modern academic process -- which @jgill confirms are mostly accurate (thanks, and yeah, I acknowledge that in practice we often fail to live up to these ideals) -- and contrasting this with the religious model of unquestionable truth handed down from on high... but also with the complete abandonment of any structured pursuit of truth, for reasons I'll go into soon.

NB that "religion" in this context is not a subject matter but a methodology; I'm not saying secular academia should go into the business of making pronouncements about God etc, but that the methods of secular academia are better ways of investigating any subject matter than the ways that religion "investigates" anything... and also, better than not having any structured social institutions of knowledge at all.

The overall thesis of this thread is that opposing religion (authoritarian institutions of supposed knowledge) doesn't mean abandoning all institutions of knowledge, and there can be education without religion. That claim on its face is pretty obvious to moderns, so mostly I'm drawing attention to the relationship between education and religion: that education is in a sense the thing that religion is nominally in the business of, telling people what supposedly is or isn't true or real, spreading supposed knowledge... and so that secular education is just a non-authoritarian version of what religion is nominally for.

Or conversely: that secular education, if made authoritarian, ends up becoming indistinguishable from religion, even if the subject matter that it talks about has nothing to do with God etc.

But also, wrt "pastors", that there is an educational role that religion fulfills that secular education does not, once again not in regards to subject matter, but methodology: I can't just pop down to the local school and float my questions about science etc to some highly-educated guy whose job it is to answer questions about that stuff, or settle disputes between people who disagree about that stuff, etc, the way that one could pop down to the local church to ask some questions about what one's religion has to say about the origins of the universe or whatever. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kActually this segues perfectly into the next bit I was about to post anyway:

Pfhorrest

4.6kActually this segues perfectly into the next bit I was about to post anyway:

Still aside from that reactive pastor role, I hold that it is also important to have, as many societies already do, more proactive roles of teachers and public educators. The role of the teacher, as distinct from the pastor, is to actively guide their students to believe things that are probably true, according to those same reference works like textbooks, rather than merely to be there to answer questions and settle arguments as they come up. The teacher provides the students with answers to questions they hadn't even thought to ask yet, and in doing so hopefully helps to prevent arguments from coming up between them in the first place.

To keep this teacher role from becoming too authoritative, though, to keep it from becoming mere indoctrination of one person by another, I think it's important to maintain a separation of the educational roles of teaching, testing, and research, much as in governance it is important to maintain a separation of powers between the executives, judiciary, and legislature. A teacher should not be teaching to texts that they wrote themselves, nor testing their own students on how well they have learned what the teacher wanted them to learn; and neither should the one doing the testing be the author of the text against which the students are tested.

Rather, the text should be a result of the global research process detailed earlier in this essay; accordance with it should be tested by someone like the pastor role described above, someone well-versed in that text; and the teaching of that text to the students should be done by a separate party, teaching to the same text as the person who will later test them, but independent of that testing. In this way the teacher cannot, upon doing their own testing, simply pass those students who they find saying things the teacher approves of and fail those who disagree, but must correctly teach an independent text that someone else, also independent of the authorship of that text, will test them against; and in this way no person involved in the education can exercise unbridled epistemic authority over their students.

Another teacher-like role, but even more proactive still, is that of public educator, who rather than guiding only those students who come to them seeking education – that being still a reactive process in a way – instead looks out over the public discourse and speaks out against falsehoods where they see them, as well as spreading true information to those who may not necessarily be looking for it. Newspapers and the like fall into this category as well as more individual agents. This begins to veer dangerously close to the public educator asserting their own epistemic authority over others, and to make sure that it does not come to that, this process must wind up turning to an independent, mutually agreed-upon "pastor" figure to settle the resulting argument, by reference to still-more-independent reference works that are the product of the global research project detailed earlier.

But I think that it is important to have such public educators going out and contesting falsehoods in the public discourse, making sure there is an argument about them and they don't just go unchallenged, even as dangerously close to authoritarianism as that might veer, because freethought is by its very anti-authoritarian nature paradoxically vulnerable to small pockets of epistemic authority arising out of the power vacuum, and if that instability goes completely unchecked, it can easily threaten to destroy the freethinking discourse entirely and collapse it into a new, epistemically authoritarian regime; a religion in effect, even if not in name. -

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Jack Cummins

5.7k

I still think your system is one which completely reinforces the status quo. Your last paragraph points out the potential danger of this. It does give too much power to the academic establishments.

Surely, in the last century we may saw a move away from the academic elite having the ultimate say about knowledge and a move towards a more lively open exchange of ideas. What you are describing sounds like a regime for killing off the true spirit of philosophical exploration and expression. Ultimately, do you think that your academic elite process of peer review would accept such a site as this, or would it seek for it to be under the control and governance of the academic 'experts'? Also, would there be more censorship of views and ideas which the academic hierarchy saw as 'false'? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSurely, in the last century we may saw a move away from the academic elite having the ultimate say about knowledge and a move towards a more lively open exchange of ideas. — Jack Cummins

Pfhorrest

4.6kSurely, in the last century we may saw a move away from the academic elite having the ultimate say about knowledge and a move towards a more lively open exchange of ideas. — Jack Cummins

Yes, but we’ve also seen a very problematic disconnect from a “common reality”, with disparate parts of society holding completely different views on basic facts and even on how to agree on what the facts are. That’s the problem with NOT having shared social institutions of knowledge.

Ultimately, do you think that your academic elite process of peer review would accept such a site as this, or would it seek for it to be under the control and governance of the academic 'experts'? Also, would there be more censorship of views and ideas which the academic hierarchy saw as 'false'? — Jack Cummins

I’m certainly not advocating censorship of any kind, and I think that a properly functioning academic structure would have to engage with the common people (like us) or else it starts to become just a religion and then that causes the exact same problem described above. I think our current version of such an academic system does not engage with the common people enough, which is partly responsible for the current crisis of “post-truth”, and that’s partly because of the missing “pastor” role I advocated earlier.

This once again segues perfectly into the next thing I was going to post anyway, so here that is...

In the absence of good education of the general populace, all manner of little "cults", for lack of a better word, easily spring up. By that I mean small groups of kooks and cranks and quacks each with their own strange dogmas, their own quirky views on what they find to be profound hidden truths that they think everyone else is either just too stupid to wise up to, or else are being actively suppressed by those who want to hide those truths from the public.

Meanwhile, those with greater knowledge see those supposed truths for the falsehoods that they are, and can show them to be such, if only the others could be engaged in a legitimately rational discourse. But instead, these groups use irrational means of persuasion to to ensnare others who do not know better into their little cults; and left unchecked, these can easily become actual full-blown religions, their quirky little forms of ignorance becoming widespread, socially-acceptable ignorance, that can appropriate the veneer of epistemic authority and force their ignorance on others under the guise of knowledge.

Checking the spread of such ignorance by challenging it in the public discourse is the role of the public educator. The need for that role would be lessened if more people would actively seek out education from teachers or pastors as I have described them above, but not everyone will seek out their own education and so some people will continue to spread ignorance – and even those who do seek out their own education may still accidentally spread ignorance – and in that event, there need to be public educators to stand against that. But that then veers awfully close to proposing effectively another "religion" to counter the growth of others.

I think there is perhaps a paradox here, in that a public discourse abhors a power vacuum and so the only way to keep religions, institutions claiming epistemic authority, at bay, is in effect to have one strong enough to do so already in place. But I think there is still hope for freedom of thought, in that not all religions are equally authoritarian: even within religions as more normally and narrowly characterized, some have their dogma handed down through strict decisions and hierarchies, while others more democratically decide what they as a community believe. I think that the best that we can hope for, something that we have perhaps come remarkably close to realizing in the educational systems of some contemporary societies, is a "religion", or rather an academic system, that enshrines the principles of freethought, and is structured in a way consistent with those principles.

Such a system of freethinking education is somewhat analogous to how, in my earlier thread on philosophy of mind, I held that "mind" in one sense is present in all matter, and neither something beyond matter that imposes itself upon matter, nor something that spontaneously arises from certain configurations of matter, but nevertheless something that can be refined by certain configurations of matter; and proper mind per se requires such configurations of matter and doesn't exist in just any random amalgam of matter, but nevertheless still consists of nothing above or beyond simply refined arrangements of the same fundamental "mind" omnipresent in all matter.

So too, here I hold epistemic "authority" to be present in all people, and neither something beyond people that imposes itself upon people, nor something that spontaneously arises from certain configurations of people, but nevertheless something that can be refined by certain configurations of people; and proper education requires such configurations of people and doesn't exist in just any random amalgam of people, but nevertheless still consists of nothing above or beyond simply refined arrangements of the same fundamental "authority" omnipresent in all people.

The ideal form of such a system of education would, I think, see the pastor role described above as the central figure, to whom laypeople come as students with questions and arguments to be resolved. Those pastors then turn, on the one hand, to the authors of tertiary sources for their knowledge, who in turn turn to authors of secondary sources, who in turn turn to the authors of primary sources; while on the other hand the pastors turn to teachers and to public educators to better inform those laypeople coming to them as students.

When there is an argument between two people who cannot mutually agree on one pastor to resolve their conflict, they can each call upon their own separate pastors to step in and resolve the argument between themselves. If need be, if they cannot reach an agreement even with their greater knowledge than their students, those pastors can turn to yet another mutually agreed upon pastor to resolve the resulting conflict between them, or else escalate further on, until at some point the argument is escalated to some parties who can work out an agreement on the matter between them, or to some mutually agreed upon arbiter who can decide the matter, and in either case then pass the decision back down the chain; unless, in the worse case scenario, an irreconcilable rift in the public discourse is discovered, in which case there is no perfect solution regardless of the system of education we have in place. -

jgill

4kA teacher should not be teaching to texts that they wrote themselves, nor testing their own students on how well they have learned what the teacher wanted them to learn; and neither should the one doing the testing be the author of the text against which the students are tested. — Pfhorrest

jgill

4kA teacher should not be teaching to texts that they wrote themselves, nor testing their own students on how well they have learned what the teacher wanted them to learn; and neither should the one doing the testing be the author of the text against which the students are tested. — Pfhorrest

Maybe in sociology, but in mathematics this is ridiculous. A professor who is a leading expert in a particular area writes a text - mostly his own discoveries in that area - and teaches a graduate seminar in that area. I would say students interested in that area benefit greatly. That's been my fortunate experience. Even as an undergraduate, a professor might teach calculus from his own text to the benefit of his students. I know of instances where this occurred. Of course, calculus has a common core and that puts it in a different category.

Your rules are inflexible. A little like the Volstead Act. -

jgill

4kThe ideal form of such a system of education would, I think, see the pastor role described above as the central figure, to whom laypeople come as students with questions and arguments to be resolved. Those pastors then turn, on the one hand, to the authors of tertiary sources for their knowledge, who in turn turn to authors of secondary sources, who in turn turn to the authors of primary sources; while on the other hand the pastors turn to teachers and to public educators to better inform those laypeople coming to them as students. — Pfhorrest

jgill

4kThe ideal form of such a system of education would, I think, see the pastor role described above as the central figure, to whom laypeople come as students with questions and arguments to be resolved. Those pastors then turn, on the one hand, to the authors of tertiary sources for their knowledge, who in turn turn to authors of secondary sources, who in turn turn to the authors of primary sources; while on the other hand the pastors turn to teachers and to public educators to better inform those laypeople coming to them as students. — Pfhorrest

And this pastor would be . . . . . . . . a philosopher? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kAnd this pastor would be . . . . . . . . a philosopher? — jgill

Pfhorrest

4.6kAnd this pastor would be . . . . . . . . a philosopher? — jgill

Not necessarily, though possibly. The job would have basically the same requirements as a general ed teacher. Someone with a wide breadth of knowledge, the ability to find good sources of deeper knowledge to pass on, and the ability to be remain neutral in disputed matters and share the arguments from all sides with those coming to him looking for answers. I hadn't thought about it but now that you bring it up it does seem like people who are good at philosophy would also likely be good at this job, but I definitely don't mean the job to be just for philosophers.

Regarding the separation of teaching, testing, and research, your response is similar to saying that sometimes it could be better if there weren't a separation of powers in government, because then a benevolent dictator could actually get some good stuff done instead of getting bogged down in all the bureaucracy. That is certainly true, but it also means that a bad dictator would go completely unchecked. The separation of powers is there for safety, to make sure that teachers don't end up as effectively priests.

Graduate studies are somewhat different, because that's on the road to becoming a researcher oneself, so it makes perfect sense that one would basically apprentice to other researchers. I'm talking about general education for the general public, not experts-in-training under the wing of other experts. -

jgill

4kyour response is similar to saying that sometimes it could be better if there weren't a separation of powers in government, — Pfhorrest

jgill

4kyour response is similar to saying that sometimes it could be better if there weren't a separation of powers in government, — Pfhorrest

Not similar, my friend. Your analogy, not mine.

General education for the general public would require testing, and by independent agencies? Sounds very Soviet. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI think you're misreading some kind of of nefarious motive in here. The point of this is explicitly to be anti-authoritarian, but it sounds like you're suggesting that I want something made more authoritarian, and I don't see why.

Pfhorrest

4.6kI think you're misreading some kind of of nefarious motive in here. The point of this is explicitly to be anti-authoritarian, but it sounds like you're suggesting that I want something made more authoritarian, and I don't see why.

Say you're a high school student, or an undergrad in college -- you know, general education, like the general public gets already. You attend a class where a teacher teaches from a textbook sourced from many different places by other people, not just his own original research -- that part is pretty normal already. Then someone else at the school administers and grades your tests to see if you've successfully learned the material as laid out in the textbook -- this is pretty much the only part we don't already do.

What's so scary or Soviet about that? -

jgill

4kSay you're a high school student, or an undergrad in college -- you know, general education, like the general public gets already. — Pfhorrest

jgill

4kSay you're a high school student, or an undergrad in college -- you know, general education, like the general public gets already. — Pfhorrest

College algebra is considered under the broad umbrella of "general education" courses. Does the general public get that already? You have a mistaken notion of "general education". I can't recall coming across a course in college called General Education. You appear to be wandering in an academic marsh here. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI don't know what point you're trying to make here. College algebra is under the umbrella of general education, yes. And that is something that is available to the general public, albeit not all of them -- which is a critique I would have of the current system too, at least undergraduate education should be available to everyone. At least at my colleges, there were "general education" requirements in common to all undergraduate degrees, regardless of major, and that's the kind of thing I'm talking about, though not specifically that. Just anything that's meant to be a recounting of the current consensus of experts, rather than specialty studies for people trying to become experts themselves, dealing in matters where there isn't yet consensus.

Pfhorrest

4.6kI don't know what point you're trying to make here. College algebra is under the umbrella of general education, yes. And that is something that is available to the general public, albeit not all of them -- which is a critique I would have of the current system too, at least undergraduate education should be available to everyone. At least at my colleges, there were "general education" requirements in common to all undergraduate degrees, regardless of major, and that's the kind of thing I'm talking about, though not specifically that. Just anything that's meant to be a recounting of the current consensus of experts, rather than specialty studies for people trying to become experts themselves, dealing in matters where there isn't yet consensus. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI'm going to continue with the new parts of this thread that I was previously going to make into new threads, but don't let that disrupt the ongoing conversation... hopefully this sheds further light on my position, if that helps:

Pfhorrest

4.6kI'm going to continue with the new parts of this thread that I was previously going to make into new threads, but don't let that disrupt the ongoing conversation... hopefully this sheds further light on my position, if that helps:

Maintaining a generally equal level of information between all the members of society is of utmost importance to making sure that such a freethinking educational system can continue to function properly, because if some people have so much more information than others, they have the ability to persuade those others to believe whatever they believe (without those others having the informational resources to properly criticize what they are told), and so begin to wield effective epistemic authority which can then easily grow into a proper religion. Because of this interdependence between liberty of thought and equal access to information, freethinking education requires what we might call a proselytizing approach to information distribution: when new information is discovered, that news must somehow become widespread, and not remain only known to those who discovered it and those closest to them.

This does not necessarily mean preaching a dogma, demanding that everyone must adopt the new findings; that would obviously be a religion, and so not freethinking. "Proselytizing" as I mean it here means only that the populace cannot be divided into those who have access to the information and those who don't. In contrast, such a division of society into those who know the important information and those who don't is what is called in religious studies "mysterianism", which many ancient religions practiced, having the greatest supposed "truths" known only to the innermost circle, with everyone else in the religion dependent on them for guidance.

Medieval European Christianity had shades of this as well with their holy text being available only in Latin and so incomprehensible to most of the congregation, making them dependent on their priests for an interpretation of the text; and newer religions like Scientology and some Wiccan traditions once again go back to a fully mysterian model as well. Even in the generally freethinking educational system that dominates in the western world today, limited public access both to educators and to research journals creates exactly the kind of wall between those who have access to information and those who don't that freethought cannot flourish in.

Freethought definitionally cannot survive alongside mysterianism, as those who held privileged access to information would merely become in effect the new religious leaders, with nobody else able to double-check and properly criticize them. Similarly, truly open proselytism, in the sense that I mean it here, cannot in practice survive alongside a religion, as whoever leads the religion controls all the information that is allowed to be disseminated, and can silence as heretical any ideas that threaten their epistemic authority (as pre-modern examples of religions silencing scientific research clearly show).

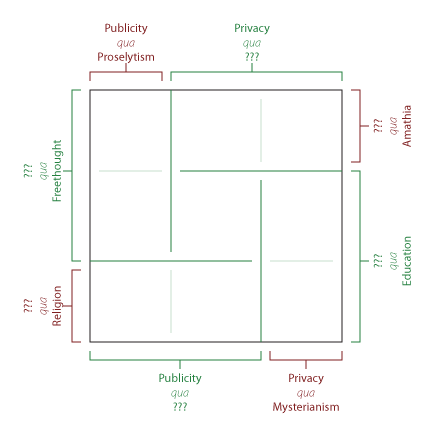

Despite the interdependence of liberty of thought and equal distribution of information described above, there is a history of both freethinking individuals secreting away the results of their research, and of course of religious proselytism, epitomized especially in Abrahamic religions like Christianity and Islam. By considering liberty of thought and equal distribution of information independently, we can create a two-dimensional spectrum of academic systems, on which such different approaches and my own position can be located. I do not actually advocate for absolute liberty of thought or absolutely equal distribution of information, but rather hold what I view to be a centrist position on both topics.

In one corner of this spectrum are the ancient mystery religions, and newer religions like Scientology that revive that mysterian approach. In another are the more familiar modern proselytizing religions. In a third corner are the freethinking researchers who withhold the information they discover from free public access, including both the likes of medieval alchemists secretly investigating ways to turn lead into gold, and the likes of modern trade-secret corporate research, and paywalled, limited-access research journals. In the last corner far opposite mystery religions would be positions that are so in favor of freedom of thought that they would oppose even non-religious education or even personal critical argument, opting for a complete "agree to disagree" attitude, and so in favor of distribution of information that they have no respect for the privacy of information that is not relevant to the public discourse.

I consider my position centrally located on this spectrum, respecting privacy and education while opposing mystery and religion.

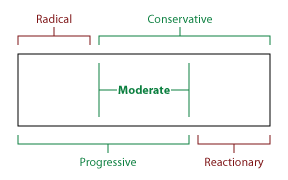

This academic spectrum is analogous to two-dimensional political spectra that juxtapose an axis of political authority or liberty against an axis of the equality or hierarchy of wealth distribution. I will address such a political spectrum in another thread later, wherein I will also discuss the relationship of the terms "conservative", "moderate", and "progressive" to such a spectrum. My view is that those terms do not refer to one of the axes of such a two-dimensional spectrum, but rather form a third axis entirely, one not about where on that two-dimension spectrum one's ideal system would fall, but how one approaches change toward their goal, wherever on the spectrum it should be. Those terms are equally applicable to a third dimension to this academic spectrum here.

In this topic as in that, I hold that the proper referent of "conservative" is someone who is cautious about change, if not completely opposed to it. Conversely I hold that the proper referent of "progressive" is someone who pushes for some change, if not complete change. And I hold that the proper referent of "moderate" is someone who is both conservative and progressive, pushing for some change, but cautious change. Those progressives who are not moderate, pushing for complete change, are properly called "radicals", and those conservatives who are not moderate, completely opposing all change, are properly called "reactionaries".

I consider myself not only a true centrist on the full spectrum described above, but also a moderate in this sense of conservatively progressive, neither radical nor reactionary. I do not view either change or stasis as inherently superior to the other, for both creation and destruction are kinds of change, and both preservation and suppression are forms of stasis, suppression negating creation just as preservation negates destruction; and it's not even inherently superior to create and preserve than to suppress and destroy, for inferior things can be created or preserved, in the process destroying and suppressing superior things, in which case it would be superior to suppress or destroy those inferior things so as to preserve and create superior ones. I support either change or stasis as they foster superior results, neither unilaterally over the other. -

jgill

4kMaintaining a generally equal level of information between all the members of society is of utmost importance . . . — Pfhorrest

jgill

4kMaintaining a generally equal level of information between all the members of society is of utmost importance . . . — Pfhorrest

I agree in theory. But making the information available doesn't necessarily mean all can or will absorb it. Nature magazine in the 1800s published breakthroughs in science and math, and at that time educated readers could comprehend much if not all that was conveyed. Nowadays specialization has made that virtually impossible. Even being a retired prof of math I can't understand half of what is conveyed to those in my profession. So, how would you overcome the inabilities of the general public to understand specialized information?

freethinking education requires what we might call a proselytizing approach to information distribution: when new information is discovered, that news must somehow become widespread, and not remain only known to those who discovered it and those closest to them. — Pfhorrest

Do you mean new discoveries in math must be promulgated to the general public and not kept locked away in incomprehensible journals for fellow experts?

I admit, when I read your posts I interpret your commentaries from the perspective of mathematics. If I were a pastor I suspect I would see things differently. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo, how would you overcome the inabilities of the general public to understand specialized information? — jgill

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo, how would you overcome the inabilities of the general public to understand specialized information? — jgill

Basically, by creating a ladder. Making more basic education available to people makes them more capable of understanding more advanced information.

But of course not everyone will be able to be a thorough expert on absolutely everything. All that’s really important is that they be up with the most current broad strokes across the board, the big picture so to speak.

Do you mean new discoveries in math must be promulgated to the general public and not kept locked away in incomprehensible journals for fellow experts? — jgill

In a sense, yes. As those new discoveries are corroborated by fellow experts the impact of them on the field as a whole should make its way into the tertiary sources that the general public learn from, and updates to those sources should be disseminated to the general public even if they’re not actively engaged in a course of training. It’s basically science news, if you count math as a science (I’m thinking much more about natural or physical sciences in most of what I’m writing here, descriptions of how the world is). Basically we need good science news. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo, on to the last part of this thread:

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo, on to the last part of this thread:

Despite the utopian ideals detailed above, I recognize also that we should not let perfect be the enemy of good, and that the choice should not be between either a perfectly functioning freethinking educational system or no educational system at all, leaving in the latter case a power vacuum for the worse kinds of religions to spring up unopposed. So it seems reasonable to me that there be in place a slightly-less-ideal, less freethinking, but for the same reason more stable system of education in place already in case the ideal one should fail; say something comparable to the most democratic of religions, proselytizing a dogma of what is most commonly and generally believed.

It should wherever possible allow the ideal freethinking solution to function and stay out of its way, and only step in to ameliorate the gravest failures that would otherwise result in a collapse to something even worse than such a democratic dogma. It may in turn be prudent to have more than just this one tier of such failsafe in place, to ensure that wherever a better system of education fails, it fails only to the next-best alternative, rather than failing immediately to the worst alternative; say a Pope-like figure elected through direct democratic vote, empowered only to re-establish a functional democratic religion, which in turn is empowered only to re-establish functional freethinking education.

I think that this kind of evolution from mystery religions toward freethinking proselytism is itself a natural progression of rational educational systems looking to preserve themselves. Authoritarianism and hierarchy may form the default form of religion, but such a religion will survive longer if it asks its congregation what they believe, and shares with them the knowledge it has accumulated, naturally inclining such authoritarian, hierarchical religions to evolve a layer of freedom and openness. Such a populist religion can then most easily appease the most people in its congregation if it simply lets them interpret their religion how they think best, and lets them exchange their own reasons for those interpretations instead of trying to do so itself, adding a layer of freethought.

Thus, the lazy selfish epistemic authority, acting in its own self-interest, naturally devolves epistemic power to its congregation; and a lazy selfish congregation, acting in its own self-interest, naturally devolves epistemic power toward more freethinking ideals; though I don't expect that this process would naturally result in the complete abolition of religion on its own.

A social discourse may in that way find itself over time sliding up and down the scale between the worst authoritarian dogma and the best freethought, depending on how well its participants manage to operate within the different possible educational systems along that scale. Because in the end, it is inherently impossible to force a people to think freely. How good of an educational system a society will support ultimately depends entirely on how much the people of that society genuinely value knowledge, because that educational system is made of people, and it is ultimately their collective pursuit of knowledge that determines how well-educated their society can be.

How exactly to help contribute toward getting enough people to pursue knowledge, reality, and truth more generally, will be the topic of a later thread.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum