-

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kI've been hoping that someone would explain and basically defend modern monetary theory, because it goes over my head even with having had university-level studies in economics and economic history. — ssu

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kI've been hoping that someone would explain and basically defend modern monetary theory, because it goes over my head even with having had university-level studies in economics and economic history. — ssu

Yeah I'm not sure I get it either. But the basic idea seems to be that countries don't seem to get financed by tax-money, as economists thought, but rather countries can just print money which only is a problem if it would create to much inflation (and we seemed to have had very little of that from the seventies onwards). The mistake was in thinking that they are regular economic entities that need to balance their books, as they can't default and print money as needed... they aren't subject to standard economic theories, but rather subject to monetary theory which comes with it's own particular set of regularities.

If true, it essentially flips things on it's head. Deficit spending is not the problem, it in fact stimulates the economy. Even moderate amounts of inflation is good because it reduces debt over time. One just has to avoid snowball inflation. -

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kThink about the debt based monetary system of ours. Basically there has to be economic growth for the interest to be paid. Then think about the "pay-as-you-go" system of pensions (and basically health care system, as old people use it far more than the young).

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kThink about the debt based monetary system of ours. Basically there has to be economic growth for the interest to be paid. Then think about the "pay-as-you-go" system of pensions (and basically health care system, as old people use it far more than the young).

Both are designed for a World were there are more younger generations than older. As I said, Japan is the case example of what is going to happen. It may not be a dramatic collapse, but Japan has serious problems. It is already in a situation where it cannot raise interest rates (as then too much of the government income would go to pay the interest). If you in this situation take more debt (as Japan has done year after year), what will you think the outcome will be? — ssu

You print money? ;-)

But, sure I get that a top-heavy demographic pyramid would cause problems for systems that were not designed with that in mind, but then you change the way you finance them?

The only "fundamental" problem it seems to me, is keeping your productivity up. You can try to increase economically active population by say increasing the pension age... or you can increase productivity by innovating production-processes. It think it would need to be a mix of both, but the latter seems promising with AI and robotization.

Imagine a World the machines are as old as B-52s are now, which the youngest bombers are 58 years old. One hundred or two hundred year old power plants. A World where your fathers computer from two or three decades ago are as fast and capable of running the current programs as a new computer you can buy from the store. — ssu

I can imagine it, but I don't see why the has to follow from population decline. Has innovation slowed down in Japan? I wouldn't know exactly, but they seem relatively up to par with the rest of the world technologically.

EDIT: You think this has to follow because less growth means less money you have to invest in innovation, right? -

ssu

9.8k

ssu

9.8k

That's the alarming issue here. There are enough smart people on the PF that at least someone ought to have understood it and be a firm believer in it...if it was an economic school of thought with genuinely valid ideas. Once there is nobody defending a position, then that position might not be so strong in the first place.Yeah I'm not sure I get it either. — ChatteringMonkey

I don't think that the MMT disagrees with the thought that printing too much money will create inflation and finally a total loss of trust in the currency (which basically is what hyperinflation is). There argument is basically that the US is different.The mistake was in thinking that they are regular economic entities that need to balance their books, as they can't default and print money as needed... they aren't subject to standard economic theories, but rather subject to monetary theory which comes with it's own particular set of regularities. — ChatteringMonkey

And I can understand this...partly: The global monetary system is based on the US dollar so much that other countries and market agents have let the US to take as much as debt it wants (which has basically been the reason why it has had the ability to be the sole Superpower in the world). Besides, their first worry would be if the dollar collapsed (would devaluate to other currencies) what will happen to their exports.

That's the name of the game now.You print money? ;-) — ChatteringMonkey

But somehow it doesn't feel like a sustainable answer. So when would you be worried about the value of the currency? When the debt-to-GDP ratio is 10 000%? When the central bank has to double it's balance sheet in six months? Or every month? Or in a week? Inflation rates in the US are creeping up now...

All this comes to mind as yesterday the richest man in the World mimicked Alan Shepard's first space flight (but not Yuri's). When the internet billionaires can do things like that, some clever things towards replacing fossil fuels can be and are done also. But what happens when those financial cornucopias suddenly dry out? Suddenly the belief in tech saving us gets a whack by an anvil in the back.

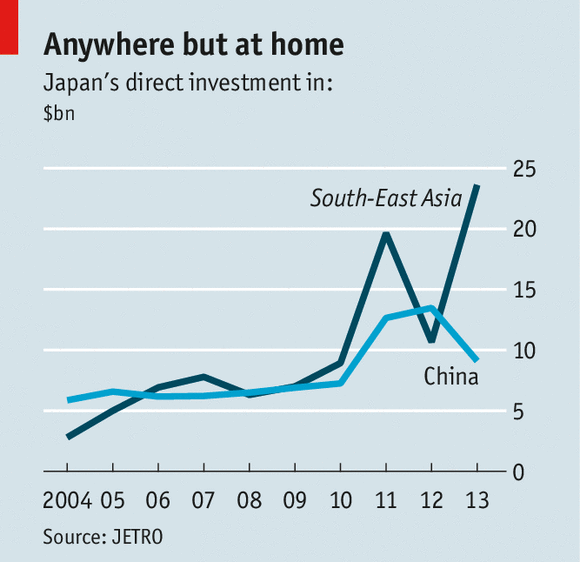

Basically the thing is that the so-called "smart money" uses the low interest rates in Japan and then uses the debt to invest in some other country (usually in China and in Asian countries).I can imagine it, but I don't see why the has to follow from population decline. Has innovation slowed down in Japan? I wouldn't know exactly, but they seem relatively up to par with the rest of the world technologically. — ChatteringMonkey

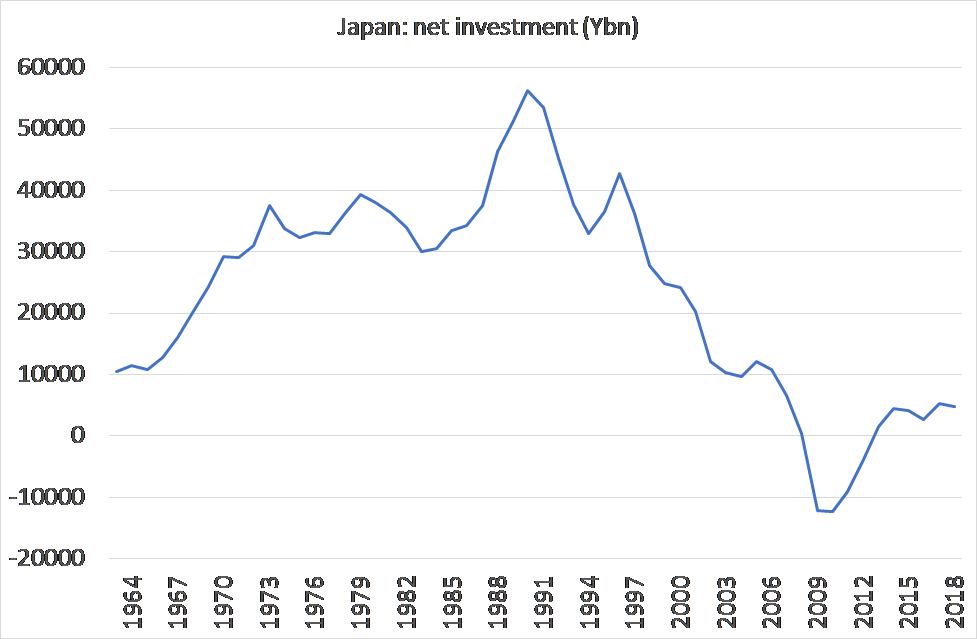

Hence the net investments in Japan have dramatically declined from earlier times:

Net investment (after covering depreciation) is very low and even gross private investment is crawling along. Japanese companies prefer to employ more labour at low wage rates rather than invest, or take their investment overseas -

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kYeah I'm not sure I get it either.

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kYeah I'm not sure I get it either.

— ChatteringMonkey

That's the alarming issue here. There are enough smart people on the PF that at least someone ought to have understood it and be a firm believer in it...if it was an economic school of thought with genuinely valid ideas. Once there is nobody defending a position, then that position might not be so strong in the first place. — ssu

Well maybe there aren't that many that have a firm grip on economy, I know I don't... it's no surprise I don't understand it.

And I take it that monetary theory is a different beast altogether, so maybe only the real specialists get it?

I don't think that the MMT disagrees with the thought that printing too much money will create inflation and finally a total loss of trust in the currency (which basically is what hyperinflation is). There argument is basically that the US is different.

And I can understand this...partly: The global monetary system is based on the US dollar so much that other countries and market agents have let the US to take as much as debt it wants (which has basically been the reason why it has had the ability to be the sole Superpower in the world). Besides, their first worry would be if the dollar collapsed (would devaluate to other currencies) what will happen to their exports. — ssu

Yes the US dollar is the reserve currency, the standard.

We haven't seen much inflation for a long time though, save for some South-American countries that did their very best to hyperinflate... so maybe it's not that big of a problem?

From what I've gathered it's not only that other countries have to let the US take debt, it's also that the world economy needs some countries to take debt, and import, to let other countries like Germany and China run an export-economy. It functions as a whole, not in isolation...

That's the name of the game now.

But somehow it doesn't feel like a sustainable answer. So when would you be worried about the value of the currency? When the debt-to-GDP ratio is 10 000%? When the central bank has to double it's balance sheet in six months? Or every month? Or in a week? Inflation rates in the US are creeping up now...

All this comes to mind as yesterday the richest man in the World mimicked Alan Shepard's first space flight (but not Yuri's). When the internet billionaires can do things like that, some clever things towards replacing fossil fuels can be and are done also. But what happens when those financial cornucopias suddenly dry out? Suddenly the belief in tech saving us gets a whack by an anvil in the back. — ssu

Maybe, don't know enough to comment with much insight here unfortunately.

Basically the thing is that the so-called "smart money" uses the low interest rates in Japan and then uses the debt to invest in some other country (usually in China and in Asian countries). — ssu

Yeah but isn't this more a function of high living standards and costs in Japan, rather than a decline in population. You see this race to the bottom everywhere.... That's another way globalization needs to be corrected I think, by taking into account social costs or lack thereof in cross-country trade-prices. -

ssu

9.8k

ssu

9.8k

The Swiss have high living standards too, yet their population is still growing. They don't have similar problems.Yeah but isn't this more a function of high living standards and costs in Japan, rather than a decline in population. — ChatteringMonkey

Population growth is the normal way for an economy to grow. Just think when people buy the most in their life: when they start a family. They likely move then to a new home, get a mortgage, buy a lot of stuff for the children etc. Afterwards the typical person doesn't do anymore such large investments like buying a home. And do note how positive this is for any economy: houses aren't built by robots in China, but by local people. So also is with the teachers that will teach the new children: again not robots in China. When the fertility rate of women is over 2, then the population is growing, hence there is a natural need for the economy to grow. Once it's less than 2 and there is no net immigration, you have a problem.

And when it comes to Japan, let's remember that there is nonexistent immigration to the country. Immigrants usually are people that want start their lives in a new country, hence they are also optimal individuals for that economic growth.

(Btw. a crazy sidenote: the dip in the Japanese fertility rate in 1966 was because of superstition about the Fire Horse) -

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kThere seems to be a myriad of reasons why the Japanese economy isn't doing so well:

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kThere seems to be a myriad of reasons why the Japanese economy isn't doing so well:

https://www.thebalance.com/japan-s-economy-recession-effect-on-u-s-and-world-3306007

But ok, you do make a good case for why decline in population, wouldn't only effect absolute growth, but also growth in terms of per capita, which I'd think is the more important number.

Then we are in a bid of a bind if we think population decline is necessary to solve a lot of our long term problems, climate change chief among them.

If we don't solve them, this will eventually have an negative impact on economy as well.

If we do want to try to solve them by lowering population among other things, we - if we assume it necessarily leads to less economic growth - will have to do with less. The total pie that can be distributed will be smaller... Best case scenario then is that we manage to spend those funds smarter and allocate them to the things that are more important. Worst case scenario, and probably more likely given how things usually go, is that the bill will have to be paid by the less affluent in the fist place... and that inequality only gets bigger. -

Benkei

8.1kI think an important way for societies to minimise the consequences is to move from shareholding to stakeholding. In my view that starts at reacquainting ourselves with the role of corporations and stock as it was understood originally. Original corporations received a charter and were gifted limited liability for activities that required a large upfront capital investment. This was considered fair in order to protect investors from liability since they did not receive a direct benefit from this investment (no interest could be calculated, no profit could be made). The goal of the corporation was limited in scope and upon reaching it the corporation would be dissolved. Why would people invest? Because the indirect benefits outweighed the capital investment. Roads, bridges, important buildings etc. were typically the subject of a corporation's charter.

Benkei

8.1kI think an important way for societies to minimise the consequences is to move from shareholding to stakeholding. In my view that starts at reacquainting ourselves with the role of corporations and stock as it was understood originally. Original corporations received a charter and were gifted limited liability for activities that required a large upfront capital investment. This was considered fair in order to protect investors from liability since they did not receive a direct benefit from this investment (no interest could be calculated, no profit could be made). The goal of the corporation was limited in scope and upon reaching it the corporation would be dissolved. Why would people invest? Because the indirect benefits outweighed the capital investment. Roads, bridges, important buildings etc. were typically the subject of a corporation's charter.

The system of stock market has been about bringing borrowers and lenders together and easing the transfer of rights related to such loans.

Where the combination went off kilter is mostly the possibility for a corporation to exist in perpetuity.

A typical bond has a maturity (there are exceptions, perpetual bonds but these were still intended to be paid off put the moment of repayment wasn't enforceable). A loan has a maturity. A mortgage has a maturity. But stock doesn't. But it doesn't fulfill an essential different role than other loan instruments but it does give a right to profit in perpetuity. And this is weird, why should a shareholder who invested 100 guilders in 1910 in Shell stock still receive dividends for Shell's activities today?

The other point is that goodwill and market value increases due to the added value of labour and nothing else (ignoring financial industry for a moment which can passively generate profit). If I put 1 million into a company it's not going to magically increase in worth, if I buy capital goods (buildings, machinery, tools) it's not going to increase in worth. If I hire people to utilise capital goods for a specific purpose, there's a likelihood something will happen with the market value of the company.

And it's clear that companies like Shell, Google, Amazon etc. are worth a multitude of the paid up capital but we insist only those that originally provided capital and any persons subsequently buying the rights related to that initial capital investment (e.g. stock) are owners of the total worth of the company and the only ones with a right to profit. Whereas if I had funded this with a loan, after say, 5 years the loan was paid off, the interest received, everything else would be owned by other people.

My point is, that at some point capital investment is not responsible for the value of a company and the relationship between profit and initial capital investment is negligible. If this is the case, I don't see an ethical reason why a shareholder should continue to receive benefits from that initial investment.

My proposed solution would involve a dynamic equity system where the initial capital investor starts out with a 100% right to the profit but as the company grows in value and this added value is the result of labour activity, additional shares are issued diluting the share value of the company. These shares will go to employees and as long as they continue to work there, they receive more shares. If they move to another company, they too will see their shares dilute over time but will build up capital in another company.

What would have to be worked out is at what rate initial capital investments should dilute. We do have a lot of bond pricing that we can use as a benchmark.

I'd also get rid of all intellectual property rights except the obligation of attribution. But different story. -

ssu

9.8k

ssu

9.8k

Btw, a consol bond is a perpetual bond without any maturity date. Hence they are considered equity rather than debt. Basically what is so wrong with equity? People have owned things, real estate and businesses and they have been inherited by their children for a long time in history. Family businesses have actually been quite persistent in history, even if sometimes there comes the generation that ruins the business (or spends the wealth away). With stocks that ownership can just be divided and easily bought and sold. I'm not so sure what is so wrong with that.A loan has a maturity. A mortgage has a maturity. But stock doesn't. But it doesn't fulfill an essential different role than other loan instruments but it does give a right to profit in perpetuity. And this is weird, why should a shareholder who invested 100 guilders in 1910 in Shell stock still receive dividends for Shell's activities today? — Benkei

Besides, saving is actually important. And many people save not only to spend later, but to have something for the "rainy day" that might never come and to give to their children when they die. If inheritance would be illegal, I guess many would simply donate part of their wealth to their children. -

Benkei

8.1kFamily businesses have actually been quite persistent in history, even if sometimes there comes the generation that ruins the business (or spends the wealth away). — ssu

Benkei

8.1kFamily businesses have actually been quite persistent in history, even if sometimes there comes the generation that ruins the business (or spends the wealth away). — ssu

Family businesses worked in their businesses too.

With stocks that ownership can just be divided and easily bought and sold. I'm not so sure what is so wrong with that. — ssu

I'm not against stock. Additional stock is issued and given to employees but can still be traded. -

ssu

9.8k

ssu

9.8k

Ok, but then our insurance system and also pension system uses these corporations too. The non-human "legal person" owner if equity is a reality. Lot of things would have to be restructured then.I'm not against stock. Additional stock is issued and given to employees but can still be traded. — Benkei

In my view the problem often is about leadership of corporations, not the existence of corporations themselves. Modern corporative structure has create a class of executive level workers who sometimes can manage the corporations wealth differently then let's say a family owned business would do: squeeze everything out and throw it away, go on some self-gratifying empire building or simply not care so much as someone who has family bonds to the enterprise. The boards are made of similar executive workers. The entrepreneur-founder CEO (Gates, Jobs etc.) is very rare occurrence. Global competition creates markets ruled by oligopolies: ten or so large companies dominate the field and then there are small local niche producers.

Of course mismanagement can happen in other business structures as co-operatives. Once a cooperative grows big enough there is the possibility of the "owners" becoming a rubber stamp and then when you have bad leadership, everything goes astray. (Reminds me of the Finnish Communist Party going bankrupt and losing a considerable fortune when cooperatives close to the party went bankrupt after a speculative market bubble burst. The few times I was genuinely spiteful. Communists as businessmen...HA!!!) -

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kI think an important way for societies to minimise the consequences is to move from shareholding to stakeholding. In my view that starts at reacquainting ourselves with the role of corporations and stock as it was understood originally. Original corporations received a charter and were gifted limited liability for activities that required a large upfront capital investment. This was considered fair in order to protect investors from liability since they did not receive a direct benefit from this investment (no interest could be calculated, no profit could be made). The goal of the corporation was limited in scope and upon reaching it the corporation would be dissolved. Why would people invest? Because the indirect benefits outweighed the capital investment. Roads, bridges, important buildings etc. were typically the subject of a corporation's charter. — Benkei

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kI think an important way for societies to minimise the consequences is to move from shareholding to stakeholding. In my view that starts at reacquainting ourselves with the role of corporations and stock as it was understood originally. Original corporations received a charter and were gifted limited liability for activities that required a large upfront capital investment. This was considered fair in order to protect investors from liability since they did not receive a direct benefit from this investment (no interest could be calculated, no profit could be made). The goal of the corporation was limited in scope and upon reaching it the corporation would be dissolved. Why would people invest? Because the indirect benefits outweighed the capital investment. Roads, bridges, important buildings etc. were typically the subject of a corporation's charter. — Benkei

Ok maybe that's how it was originally intended, I don't know the history of it, but that doesn't mean that it has to stay that way. Things morph and get used in other ways/get other functions over time, and in principle that perfectly fine.

Limiting liability seems necessary to incentivise any type of investment in larger companies. Typically the amount of money any one person has is insignificant in relation to the amounts of money circulating in the books of any decent sized company. If you wouldn't limit liability, a company of any decent size failing, would typically mean the investors would be in debt for the rest of their lives. So even if there were only a small chance of failing, nobody would want to take that chance because very few things are worth the risk of being financially crippled for the rest of your life.

The system of stock market has been about bringing borrowers and lenders together and easing the transfer of rights related to such loans.

Where the combination went off kilter is mostly the possibility for a corporation to exist in perpetuity.

A typical bond has a maturity (there are exceptions, perpetual bonds but these were still intended to be paid off put the moment of repayment wasn't enforceable). A loan has a maturity. A mortgage has a maturity. But stock doesn't. But it doesn't fulfill an essential different role than other loan instruments but it does give a right to profit in perpetuity. And this is weird, why should a shareholder who invested 100 guilders in 1910 in Shell stock still receive dividends for Shell's activities today? — Benkei

Isn't the issue just ownership, property here? A share is a piece of ownership right? Suppose there were no shares, everything would stay with the founder/owner of the company and you'd have essentially the same problem of a person getting a return on his initial investment in perpetuity.

The other point is that goodwill and market value increases due to the added value of labour and nothing else (ignoring financial industry for a moment which can passively generate profit). If I put 1 million into a company it's not going to magically increase in worth, if I buy capital goods (buildings, machinery, tools) it's not going to increase in worth. If I hire people to utilise capital goods for a specific purpose, there's a likelihood something will happen with the market value of the company. — Benkei

This seems a bit oversimplified, and may in the future even not be the case anymore as labour could presumably be a thing for automation... but ok I'll follow along.

And it's clear that companies like Shell, Google, Amazon etc. are worth a multitude of the paid up capital but we insist only those that originally provided capital and any persons subsequently buying the rights related to that initial capital investment (e.g. stock) are owners of the total worth of the company and the only ones with a right to profit. Whereas if I had funded this with a loan, after say, 5 years the loan was paid off, the interest received, everything else would be owned by other people.

My point is, that at some point capital investment is not responsible for the value of a company and the relationship between profit and initial capital investment is negligible. If this is the case, I don't see an ethical reason why a shareholder should continue to receive benefits from that initial investment.

My proposed solution would involve a dynamic equity system where the initial capital investor starts out with a 100% right to the profit but as the company grows in value and this added value is the result of labour activity, additional shares are issued diluting the share value of the company. These shares will go to employees and as long as they continue to work there, they receive more shares. If they move to another company, they too will see their shares dilute over time but will build up capital in another company.

What would have to be worked out is at what rate initial capital investments should dilute. We do have a lot of bond pricing that we can use as a benchmark.

I'd also get rid of all intellectual property rights except the obligation of attribution. But different story. — Benkei

You want to distribute added value to everybody that has contributed to it, and not only to the owners. I can get behind that goal certainly. And the idea of giving out shares which dilute over time seems like a clever way to do that. No sure how it would work out in practice, but at least it's a concrete idea to try to solve the issue, got to give you props for that! -

Benkei

8.1kLimiting liability seems necessary to incentivise any type of investment in larger companies. Typically the amount of money any one person has is insignificant in relation to the amounts of money circulating in the books of any decent sized company. If you wouldn't limit liability, a company of any decent size failing, would typically mean the investors would be in debt for the rest of their lives. So even if there were only a small chance of failing, nobody would want to take that chance because very few things are worth the risk of being financially crippled for the rest of your life. — ChatteringMonkey

Benkei

8.1kLimiting liability seems necessary to incentivise any type of investment in larger companies. Typically the amount of money any one person has is insignificant in relation to the amounts of money circulating in the books of any decent sized company. If you wouldn't limit liability, a company of any decent size failing, would typically mean the investors would be in debt for the rest of their lives. So even if there were only a small chance of failing, nobody would want to take that chance because very few things are worth the risk of being financially crippled for the rest of your life. — ChatteringMonkey

Limiting liability was indeed necessary to incentivize investment in undertakings that wouldn't yield profit. Adding the possibility to corporations to make profit could've been incentive enough (partnerships don't have limited liability either) but politics resulted in profit and limited liability. I think that was a mistake. Limited liability externalises the costs of damages caused by the corporation to wider society, which is a reasonable exchange if the corporate activity is performed for a goal benefiting wider society but not if it's only for private gain. In that case, if you have all the profits, you should also bear all the responsibility.

In my ideal world, we would see non-profit pharmaceutical companies developing the "riskiest" treatments with limited liability and for-profit pharmaceutical companies but with normal liability that would automatically go for simpler products.

An alternative effect could also be that much of the useless day trading resulting in value extraction from the real economy and rent seeking could be entirely avoided if limited liability would be repealed for every corporation. You can also get rid of IFRS and GAAP accounting principles at the same time as no investor is going to touch a stock without having the necessary information to ensure they're duly informed about the risks of their investments if they would be liable for losses.

Isn't the issue just ownership, property here? A share is a piece of ownership right? Suppose there were no shares, everything would stay with the founder/owner of the company and you'd have essentially the same problem of a person getting a return on his initial investment in perpetuity. — ChatteringMonkey

That's how it was defined. It could also have been structured as a piece of a loan and related interest, pretty much like a variable interest rate bond, possibly collateralised but not necessarily involving ownership in property of the corporation directly. I do think that now that it is considered "property" there's a lot more resistance to making changes to how corporations are set up.

You want to distribute added value to everybody that has contributed to it, and not only to the owners. I can get behind that goal certainly. And the idea of giving out shares which dilute over time seems like a clever way to do that. No sure how it would work out in practice, but at least it's a concrete idea to try to solve the issue, got to give you props for that! — ChatteringMonkey

Thanks. Glad it's not served off as evil communism from the get-go! -

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kLimiting liability was indeed necessary to incentivize investment in undertakings that wouldn't yield profit. Adding the possibility to corporations to make profit could've been incentive enough (partnerships don't have limited liability either) but politics resulted in profit and limited liability. I think that was a mistake. Limited liability externalises the costs of damages caused by the corporation to wider society, which is a reasonable exchange if the corporate activity is performed for a goal benefiting wider society but not if it's only for private gain. In that case, if you have all the profits, you should also bear all the responsibility.

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kLimiting liability was indeed necessary to incentivize investment in undertakings that wouldn't yield profit. Adding the possibility to corporations to make profit could've been incentive enough (partnerships don't have limited liability either) but politics resulted in profit and limited liability. I think that was a mistake. Limited liability externalises the costs of damages caused by the corporation to wider society, which is a reasonable exchange if the corporate activity is performed for a goal benefiting wider society but not if it's only for private gain. In that case, if you have all the profits, you should also bear all the responsibility.

In my ideal world, we would see non-profit pharmaceutical companies developing the "riskiest" treatments with limited liability and for-profit pharmaceutical companies but with normal liability that would automatically go for simpler products. — Benkei

I don't think profit alone would be enough, as the upside of profit for someone who already has enough money (which are typically the ones to invest), isn't worth the risk of being in debt for the rest of your life. Maybe it works for smaller business where the stakes are not that high, but otherwise it seems that removing limited liability would lead to less investment and less incentive to grow into larger corporations. And you know, there may be something to that, one of the problems is that we have these mega multi-national corporations that float somewhere over and between countries in a globalised world... they do have to much power.

Maybe one should pay a tax or something like that, for limiting liability, to pay for the externalised costs of potential damages caused by the corporation... like an insurance-fee where the fee is calculated based on the risks and the amount that is insured. Come to think about it, that's what it is now essentially, a free insurance against the averse consequences of failing that is paid by society, or by the creditors more specifically.

So maybe that's how it would go if you'd remove the limited liability granted by law, they would look for an insurance-type deal in the market to mitigate the risk. Then they have to pay a fee that covers the costs. And where the risks and fee-costs would be to high, government could always intervene for essential goods and services...

That's how it was defined. It could also have been structured as a piece of a loan and related interest, pretty much like a variable interest rate bond, possibly collateralised but not necessarily involving ownership in property of the corporation directly. I do think that now that it is considered "property" there's a lot more resistance to making changes to how corporations are set up. — Benkei

Sure you could set up shares in another way for the purpose of attracting investment, but then you still have the issue of the owner raking in all the profit indefinitely no? Someone has to set-up the corporation initially and owns it, or how would that work otherwise? -

Punshhh

3.6kInteresting ideas, but I have given this some thought and came up with a problem. The rich, some successful business people, elites and privileged people will resist the degree of sharing and cooperation required for any of these solutions to solve the problem.

Punshhh

3.6kInteresting ideas, but I have given this some thought and came up with a problem. The rich, some successful business people, elites and privileged people will resist the degree of sharing and cooperation required for any of these solutions to solve the problem.

Rather what I see is the super rich hoarding as much wealth as they can, by unscrupulous means sometimes. Also powerful people might prefer to live in a dystopian world, than a progressive sustainable world.Because of this fear of sharing that will be required and to continue exploitation and profiteering. -

Benkei

8.1kI sincerely doubt it can work in several jurisdictions now that some corporations can claim human rights protections. I do think this can be incentived though. If a corporation is set up in such a way profits are more equitably distributed to stakeholders then wealth transfer tax mechanism can be waived, leading to lower taxes which should make the after tax profit much higher.

Benkei

8.1kI sincerely doubt it can work in several jurisdictions now that some corporations can claim human rights protections. I do think this can be incentived though. If a corporation is set up in such a way profits are more equitably distributed to stakeholders then wealth transfer tax mechanism can be waived, leading to lower taxes which should make the after tax profit much higher. -

ssu

9.8k

ssu

9.8k

In any situation those that have power will not want to lose their power, hence societal change is always difficult, no matter what the situation is. And do notice that not in all societies it's just a extremely rich who have the power, in many places there is a small cabal of career political people who are in charge and who aren't exactly super rich. Thinking that in every country the rich control everything is an exaggeration.The rich, some successful business people, elites and privileged people will resist the degree of sharing and cooperation required for any of these solutions to solve the problem.

Rather what I see is the super rich hoarding as much wealth as they can, by unscrupulous means sometimes. Also powerful people might prefer to live in a dystopian world, than a progressive sustainable world.Because of this fear of sharing that will be required and to continue exploitation and profiteering. — Punshhh

And if you go for the wealth of the rich, the next in line all the way down to the middle class will be worried when you will go after their wealth too. Killing the rich, a genocide by class, has been several tries been done or attempted and the outcome hasn't been a rosy one, but a huge tragedy.

The most important issue is to have social cohesion and make sure that doesn't vanish. Then changes, even radical ones, are possible. Without social cohesion the society simply doesn't work. -

Punshhh

3.6kYes, we only need look at the tobacco, or oil lobbies.

Punshhh

3.6kYes, we only need look at the tobacco, or oil lobbies.

Here in the U.K. we have a distinct privileged class. An overthrow of our class system. These people are dead against any kind of levelling up, or Universal basic income. It suits them fine for the status quo to continue, by propping up a Tory government. This is entrenched, because they only have to think about the alternative and they are horrified, this prejudice is more than financial, or economic. It’s social and cultural too. Personally I trace it right back to the Norman conquest and our country being ruled over for centuries by French overlords. Johnson has stepped into that role, groomed by Eton college and Oxford. -

ssu

9.8k

ssu

9.8k

In my view the UK has a distinct and quite strict class system, where it isn't just the upper class that preserves and maintains the class structure. When you can notice the class from language, hobbies and the sports people watch, the class system has quite deep roots. For British what class they come from is very important.Here in the U.K. we have a distinct privileged class. An overthrow of our class system. — Punshhh

Yet you have universal health care and the Labour party. Something which actually the US doesn't have.These people are dead against any kind of levelling up, or Universal basic income. It suits them fine for the status quo to continue, by proving up a Tory government. — Punshhh

And just like the Labour Prime Ministers Tony Blair, Harold Wilson and Clement Attlee who also graduated from Oxford. And btw, Keir Starmer, the present leader of the Labour party and the opposition leader has also graduated from Oxford. You see societies that function basically as meritocracies do not erase classes. Those who get to the top universities will make the future elite, independently of what their political views are. France is another example of this.Johnson has stepped into that role, groomed by Eton college and Oxford. — Punshhh -

Punshhh

3.6k

Punshhh

3.6k

It’s difficult to provide proofs for things like global tipping points. The signs are there and arguably the tipping point is reached somewhere we are not aware of at a time we are not aware of.

There is no doubt that the permafrost is melting all around the northern hemisphere as is documented in this article.

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00659-y

This was published before the record heatwaves in those areas just a few weeks ago. I don’t have figures for how much methane will be released. It won’t require much though to nullify all our efforts to reach carbon zero, as methane is at least 25 times more effective as a greenhouse gas than CO2.

This combined with our lethargy in reaching carbon zero and the continued cutting down of forest(which is still increasing). Is a clear enough sign for me. -

boethius

2.7kIt’s difficult to provide proofs for things like global tipping points. — Punshhh

boethius

2.7kIt’s difficult to provide proofs for things like global tipping points. — Punshhh

I definitely agree in a formal sense of "proof". However, tipping points are a general characteristic of complex systems we can pretty much always safely infer will be present in any such system.

There is mathematical work on this I saw a few years ago, I'll try to find, trying to quantify mathematically what is meant by tipping point and what conditions are necessary for tipping points to exist.

One interesting result of this work is that in systems with internal variables (things as they are) and external variables (things we can observe) tipping points can be triggered without any way to know based on the external variables (there is nothing that can track the actual tipping point, but it will only be inferrable in the future, that it happened at some point, in retrospect).

And this aligns well with our intuition. For instance, if we take people as complex systems, they do unpredictable things all the time (or then expected actions but at unpredictable times) and presumably hit tipping points that lead to such actions, but we can't really tell when exactly tipping points were. For instance, we may know someone unhappy at their work and expect them to quit at some point, and maybe many times something happens that seems "the last straw" but it isn't, but finally there is a last straw, that we didn't even see happening, and the person quits. An even more stark example is someone who is unhappy at their work, but is not expressive about it, and we don't suspect a thing, but someday they quit, and we can, in retrospect, assume some tipping point was reached that lead to the "radical simplification" of the work situation (at least temporarily).

But basically, all complex systems (we tend to encounter) respond to too much stress by simplifying (not getting more complex; a bit of stress may do that, but at some point there is a threshold that leads to simplification).

All this to say, and I'm sure you agree, that it's best not to push towards such thresholds on a global scale to see what happens.

What we can be relatively certain is that "pushing harder" on the climate isn't going to paradoxically make things better in any scenario, but we should stop pushing, hope for the best, and plan for both "radical simplification" as well as "keeping it together somewhat". -

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kHere's a podcast that deals with some of the issues we have touched on in this thread:

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kHere's a podcast that deals with some of the issues we have touched on in this thread:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mk1pIKI72jg

It's basically a debate around the question "Is the end of capitalism the answer to climate change?" One of the speakers argues for and the another against... Both present arguments worth looking into IMO.

The speaker on the side of 'capitalism is the problem' sets the stage by claiming there are inherent tendencies in capitalism that make a solution to the problem difficult and yes that capitalism has in part been the cause of the problem :

- Growth is inherent in capitalism. And so more of everything is needed, not in the least energy, so to reduce carbon emissions we have to swim upstream if our economy relies on growth.

- Money can buy anything in the natural world.

- The promise that everybody will have more luxuries. A world wherein everybody lives in luxury is not feasible and incompatible with avoiding climate change.

On the side of 'climate change can be solved within capitalism' the speaker makes a reasonable argument I think that we have dealt with some environmental and pollution issues in the past in capitalist countries, and so solving a similar problem is in principle feasible in a capitalist system... by passing legislation that takes into account environmental costs or legislation that just forbids certain things. The counter being given to this argument is that we have known about climate change for a long time now and still haven't really made any progress... part of the problem in capitalism is that money translates into political power (lobbying) and that this has prevented adequate legislation that might address the issue.

Another point worth mentioning on the pro-capitalism side is that the promise capitalism makes of luxury is a just another way of framing a basic human desire for prosperity, flourishing, and not really something unique to capitalism. And so doing away with capitalism won't actually do away with this desire, and would in any case be hard to sell to the public. Interesting points are being made that GDP is not the same as human flourishing etc..

Asked for an alternative to capitalism, the speaker on the side of 'capitalism is the problem' points to a system of commons which he think can fulfill the desire for prosperity by better and more shared commons, in stead of it being fulfilled by private property. Counter to this is that we don't have any idea how and if this would work on the larger scales that we would need it to work on given current world population.

My own assessment of the debate is that while there is more than grain of truth in the statement that capitalism has caused climate change and makes it more difficult to solve it because of perpetual growth, I don't really see a clear alternative. Maybe it's possible to eventually radically change our system, I just don't see it happening fast enough. It's not like we have a another couple of decades to sort this out first. The political will doesn't seem to be there for this kind of change, at this moment anyway, and even if the will would be there these kind of changes typically don't come without massive societal upheaval. How are we going to find the persistent agency to rapidly change our energy system into renewals in this kind of turmoil?

In principle growth doesn't seems necessarily tied to increase in emissions. You need energy yes, but that need not be based on carbon emissions. Long term growth and therefor capitalism is not sustainable I think because of other reasons, but that's another discussion. Also the argument that capitalism skews political decision-making and makes a solution more difficult is not lost on me either, but I think it's more likely that we find ways to deal with that, than it is to change the whole system and hope that we can do that fast enough and end up with a system that can deal with the issue adequately (which is not a given either). -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kAnother point worth mentioning on the pro-capitalism side is that the promise capitalism makes of luxury is a just another way of framing a basic human desire for prosperity, flourishing, and not really something unique to capitalism. — ChatteringMonkey

Kenosha Kid

3.2kAnother point worth mentioning on the pro-capitalism side is that the promise capitalism makes of luxury is a just another way of framing a basic human desire for prosperity, flourishing, and not really something unique to capitalism. — ChatteringMonkey

If you have to manipulate your customers to want the luxury in the first place, and the means by which organisations do this are varied, sly and grim, then this doesn't really hold up. -

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kHere's a podcast on the difficulties in communicating the science of climate change to the public:

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kHere's a podcast on the difficulties in communicating the science of climate change to the public:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xdjLK4Qm86I

Basically to much and to little has been made of the 2030 'deadline' in the IPCC report on climate change.

To much in the sense that it is not supposed to be a hard "dead"-line... the world is not going to end in 2030. It was meant more as a deadline for societal change, i.e. if we want to get to carbon-neutrality in 2050, we should be well on our way in 2030 otherwise it's only going to get progressively difficult. Transition takes time...

And to little in the sense that despite the promises no a whole lot has happened in the meanwhile. Essentially the problem is that politicians aren't willing to move unless there is enough public support, so the question ends up being how do you get public support? There's some interesting discussion and different viewpoints on how to get that public support and best ways to communicate about the issue.

Also some info on the uncertain science behind tipping-points...

There are further episodes in this series which is on the whole excellent I think. -

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kAnother point worth mentioning on the pro-capitalism side is that the promise capitalism makes of luxury is a just another way of framing a basic human desire for prosperity, flourishing, and not really something unique to capitalism.

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kAnother point worth mentioning on the pro-capitalism side is that the promise capitalism makes of luxury is a just another way of framing a basic human desire for prosperity, flourishing, and not really something unique to capitalism.

— ChatteringMonkey

If you have to manipulate your customers to want the luxury in the first place, and the means by which organisations do this are varied, sly and grim, then this doesn't really hold up. — Kenosha Kid

Yes I agree for the most part. Human flourishing, or even simply prosperity, is something else than what we have been sold in capitalism. But so while this is true, part of the point that we still would need a system that could provide "prosperity/flourishing" stands I think. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kpart of the point that we still would need a system that could provide "prosperity/flourishing" stands I think. — ChatteringMonkey

Kenosha Kid

3.2kpart of the point that we still would need a system that could provide "prosperity/flourishing" stands I think. — ChatteringMonkey

I dunno. Maybe because now we're anchored to the myth of sustainable growth, it might be difficult to sell real sustainability. But again I feel that this is something that's been indoctrinated rather than meeting some demand. There is a very powerful (I can't say "good") capitalist reason to compel earners to exchange their salaries for luxuries, so if you live in a capitalist democracy, no one's going to allow the electorate to labour under the belief that keeping more of their earnings for the future is a good idea. But we used to do just that. Saving and thrift were virtues once. -

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kpart of the point that we still would need a system that could provide "prosperity/flourishing" stands I think.

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kpart of the point that we still would need a system that could provide "prosperity/flourishing" stands I think.

— ChatteringMonkey

I dunno. Maybe because now we're anchored to the myth of sustainable growth, it might be difficult to sell real sustainability. But again I feel that this is something that's been indoctrinated rather than meeting some demand. There is a very powerful (I can't say "good") capitalist reason to compel earners to exchange their salaries for luxuries, so if you live in a capitalist democracy, no one's going to allow the electorate to labour under the belief that keeping more of their earnings for the future is a good idea. But we used to do just that. Saving and thrift were virtues once. — Kenosha Kid

I'm not talking about luxuries, but about needs. Part of it is indoctrination yes, or just plain advertising I guess. And so I agree with you as far as western countries go, in principle we have more than enough to fulfill our needs. This is not the case in developing countries I don't think... real sustainability would probably require some increase in "general wealth". As their population has boomed it's hard to see how one would return to small scale sustainability. Those countries also happen to be the real problem for reducing carbon emissions going forward. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kAs their population has boomed it's hard to see how one would return to small scale sustainability. — ChatteringMonkey

Kenosha Kid

3.2kAs their population has boomed it's hard to see how one would return to small scale sustainability. — ChatteringMonkey

And yet the more people, the less of a share of the Earth's resources they should have. But yeah I understand your point about poorer countries levelling up, and this only reinforces the need for richer countries to recede. The growing emissions of the third world are principally a problem while the first world is already unsustainably over-emitting. If we drop back, there's wiggle room to approach equilibrium. -

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kAs their population has boomed it's hard to see how one would return to small scale sustainability.

ChatteringMonkey

1.7kAs their population has boomed it's hard to see how one would return to small scale sustainability.

— ChatteringMonkey

And yet the more people, the less of a share of the Earth's resources they should have. But yeah I understand your point about poorer countries levelling up, and this only reinforces the need for richer countries to recede. The growing emissions of the third world are principally a problem while the first world is already unsustainably over-emitting. If we drop back, there's wiggle room to approach equilibrium. — Kenosha Kid

Yes, we certainly bear a historic and moral responsibility, though there isn't much wiggle room even if we'd cut emissions entirely, if we want to reach emission targets that is. The best hope for getting there is that we develop green alternatives and that developing countries can 'leapfrog' to those technology by learning from us and directly implementing them. But this brings me back to the point of why we may need at least some of the production capacity capitalism has provided us, to be able to build these green alternatives on a large enough, and therefor cheap enough, scale. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kYeah I'm in the green technology camp (my energy provider is 100% renewable, for instance), but to be fair that's to deal with a problem _caused_ by capitalism. Technology is what has to save us from irresponsible use of technology.

Kenosha Kid

3.2kYeah I'm in the green technology camp (my energy provider is 100% renewable, for instance), but to be fair that's to deal with a problem _caused_ by capitalism. Technology is what has to save us from irresponsible use of technology.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum