-

Noble Dust

8.1kSome people wonder why Americans are so religious. (They are compared to Europe, especially). I would say it is (at least to some extent) BECAUSE there has been so much splintering. Every time a group divides, it is re-energized. — Bitter Crank

Noble Dust

8.1kSome people wonder why Americans are so religious. (They are compared to Europe, especially). I would say it is (at least to some extent) BECAUSE there has been so much splintering. Every time a group divides, it is re-energized. — Bitter Crank

Eh, what you say about gaining energy through forming a new denomination is undoubtedly true, but there are other reasons America is so Christian. And as far as ethnic sects of the same denomination of Christianity within America, those existed because of immigration; early immigrants stuck together with those of their same race; naturally their unique form of the faith remained in tact while those close-knit communities did so. Once those ethnic communities began to splinter, the ethnic sects of the denominations began to blur.

There was quite a bit of competition: Baptists vs. Methodists; Lutherans vs. Catholics; Presbyterians vs. Congregationalists, etc. and not just good-natured competition. — Bitter Crank

I don't think there was actual competition between denominations in the early US; the denominations were again cultural, not specifically theological. To the contrary, those denominations would have rather retained only members of their ethnic group, early on. Economics as much as anything else are what caused those ethnic lines to dissolve. From there, I think theological problems were afterwards more responsible for the proliferation of endless new denominations. -

Cavacava

2.4k

Carl Schmitt asserted that "All significant concepts in the modern theory of the state are secularized theological concepts"

— Cavacava

AT LAST!!! The occasion where one of my favorite quotes (since 1983) is appropriate: "Everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics." Charles Peguy (a late 19th century early 20th century Frenchman).

The secularization of the mystical also secularized need for religious purity, which becomes violence in its secularization. For some this became the quest for ethnic/class purity as sought by the Nazis, Stalin & Lenin.

This is why many hold that there can be no exceptions to law, that all laws flow from norms, and the judiciary like priests there to interpret what the law entails. [reminds me of the debate between the divine command theory versus the restriction of God by his laws] The US Constitution has a statement regarding the availability of exceptions to the legislative branch. The following from Article III section 2 of the US Constitution:

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

This is a big gaping exception that means that Congress can craft a law not subject to judicial review. While questioned by justices (John Marshall 1803), there are no laws I am aware of crafted using this exception, but it was attempted in the Marriage Protection Act of 2003 which passed the House but failed in the Senate. Here from the proposed law:

WikipediaNo court created by Act of Congress shall have any jurisdiction, and the Supreme Court shall have no appellate jurisdiction, to hear or decide any question pertaining to the interpretation of, or the validity under the Constitution of, section 1738C or this section. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

I think you've set up a division between what is known by human beings in general, and what is practised by particular individuals, and then you try to relate this to "evolution". The problem being that individuals do not "evolve" in any way which is related to the concept of "evolution", So it appears to me like you freely cross category boundaries, perhaps committing category error.

The difference is knowledge versus practice. This is where religious life comes into play. — Noble Dust

So you start off with this distinction of knowledge versus practise, and how it relates to religion. I would assume that "knowledge" here refers to what is held by the religion in general, and "practise" refers to the actions of individuals. If we want to produce categorical consistency, we need to bring "knowledge" into the minds of the individuals. So we make it clear, and unambiguous, that "knowledge" here refers to beliefs which are held by the individual, within the individual's mind. "Religion" then must be a particular type of belief which one holds, a belief in God or some such thing, which is part of an individual's knowledge.

There is a difference between "knowing", or being able to "distinguish right and wrong" in a more and more nuanced way, versus applying that knowledge towards an everyday practice. You seem to assume that the two are interchangeable. This is actually classic Biblical wisdom; it's "head knowledge versus heart knowledge" (ugh, what a gross phrase, yet so true). Practice means consciously applying the actual concepts; things like charity, unconditional love, meditation — Noble Dust

Now you need to justify this distinction between head knowledge and heart knowledge, the difference between knowing what is right and wrong, and practising what is right rather than practising what is wrong. So let's say that "knowing what's right and wrong", consists of general principles which one holds, and let's say that practise consists of applying general principles to particular situations. So the distinction here is between what is held in one's memory, and what is actually going through one's mind at a particular time. We can refer to Augustine's tripartite mind, memory (principles held within), intellect (what's actually going on in one's mind, active thought), and will (that which ends the activity, the decision).

This is what I mean by "moral evolution of the inner life of the individual". What I mean is: There is not an evolution of more and more people applying the more and more nuanced moral concepts we have to their everyday practice. What we have instead is that the general knowledge of moral problems becomes more and more nuanced over time, but this has nothing to say about the actual application of that knowledge by individuals to their lives. — Noble Dust

So this doesn't make a lot of sense to me. You refer to "nuanced moral concepts", Does that mean that there are differences in the moral principles which one has to remember. Does this mean that a child can remember the same fundamental moral principle in a number of different ways, such that each way has a subtle difference from the other? So when that person is later in some particular situation, and applying the moral principle, using the intellect, the person can decide, "I like this version of that principle better than that version", so I'm going to apply this version of that principle in this situation?

Is that what you mean when you say that the knowledge of moral concepts becomes "more and more nuanced over time"? It cannot be that the concept acquires more and more particularities, because then it would become less and less applicable. In order to be applicable to the widest range of particular situations, the principle must become more and more general.

In fact, if anything, the ever-increasing complexity of moral problems just serves to confound the average person, leaving them to fall back on whatever political or religious sentiment is convenient and sufficient enough to stay the tide of overwhelming moral dilemmas that our current world consists of. This is ultimately not about abstract philosophy; it's about personal practice. Morals always ultimately come down to this: the individual person. Conceptions of morality that don't revolve around the individual de-humanize the individual, which is to say that they de-humanize humanity itself. — Noble Dust

Here, you need to distinguish between complexity in the world we live in, and complexity in the moral principles which guide our actions. What is confounding the average person is the complexity of the world which we live in, this is the individual's environment. The individual need not adopt complex and confounding moral principles. One can take something simple, like "love thy neighbour", and cling to this as the highest guiding principle. But in a complex societal environment, one might choose a different highest principle, like "be loyal to your family", or "be patriotic". Choosing a different one of each of these principles to support one's practise, as a highest guiding principle, could produce a radically different practise, depending on which one is chosen.

A complex social environment may make it more difficult for one to properly maintain a hierarchy of moral values, requiring more effort, but an individual cannot blame the societal environment for holding a corrupt hierarchy. This would be to shirk one's responsibility by claiming determinism.

So I disagree with you to a large extent. Yes, I agree that it is "about personal practise", because personal practise is what affects the world, what we observe, and how we judge people. But the "abstract philosophy" consists of the guiding principles which influence one's personal practise, so what morality is "really about" is these abstract principles. To slip in one's adherence to the highest principle is what causes corrupt practise. To hold a "nuanced" highest principle within your mind (memory), i.e. to have a choice of highest principles, is that slippage.

To turn the other way now, away from such slippage and corruption, toward the good, we should seek to more clearly define that highest principle, make it more universal acceptable, and more universally applicable. We should establish the necessity and facilitate the application of the highest principle. Looking back at the foundations of Christianity we can see how Jesus' message of love evolved into forgiveness before going into the stages of corruptive decline. I believe we must renew the highest principle, and that we have not completed the evolution of the highest principle.

This is a classic conflation of survival with moral good. Survival is a mechanism of material evolution; taking this mechanism and applying it to the realm of morals is a misapplication, and this is why: To assume that morals are a function of survival undermines evolution itself; so if evolution is based on change, then there will be a change from survival to something else. Morals are a function of that new form of change, and we live in that world now. Our evolution is no longer based on survival. — Noble Dust

This really doesn't make any sense to me. You have already denied "moral evolution", claiming that there is no such thing, and this I objected to. All you do here is assert that there is no relationship between morality and survival, so you are just begging the question. Your support for this assertion makes no sense to me. How would a relationship between morality and survival undermine evolution itself? -

BC

14.2kEh, what you say about gaining energy through forming a new denomination is undoubtedly true, but there are other reasons America is so Christian. And as far as ethnic sects of the same denomination of Christianity within America, those existed because of immigration; early immigrants stuck together with those of their same race; naturally their unique form of the faith remained in tact while those close-knit communities did so. Once those ethnic communities began to splinter, the ethnic sects of the denominations began to blur. — Noble Dust

BC

14.2kEh, what you say about gaining energy through forming a new denomination is undoubtedly true, but there are other reasons America is so Christian. And as far as ethnic sects of the same denomination of Christianity within America, those existed because of immigration; early immigrants stuck together with those of their same race; naturally their unique form of the faith remained in tact while those close-knit communities did so. Once those ethnic communities began to splinter, the ethnic sects of the denominations began to blur. — Noble Dust

The Second Great Awakening (late 18th, early 19th Centuries) was another reason for religion doing well in the U.S. The SGA was led by Methodist and Baptist preachers. (Baptists hadn't become conservative Southern Baptists yet). The SGA was a continuing stimulant well into the 19th Century.

Because Americans had no state-sponsored church, we were free to wander into all sorts of oddball beliefs. The SGA produced the "burnt over area" of Western New York--an area so heavily evangelized, that all the "fuel" for future conversions had been "burnt up". Several groups sprouted in that area about that time: Mormons, 7th Day Adventists, Jehovah's Witnesses, Shakers, et al. In addition, the feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Women's suffrage movement started here. The Fourierist utopian socialists, as well as the Oneida Society began here. Walter Rauschenbusch and the Social Gospel came out of this area.

Immigration did influence Christian and Jewish religious activity. Over time (like, by the 1970s) the ethnic-religious nexus was dissipating.

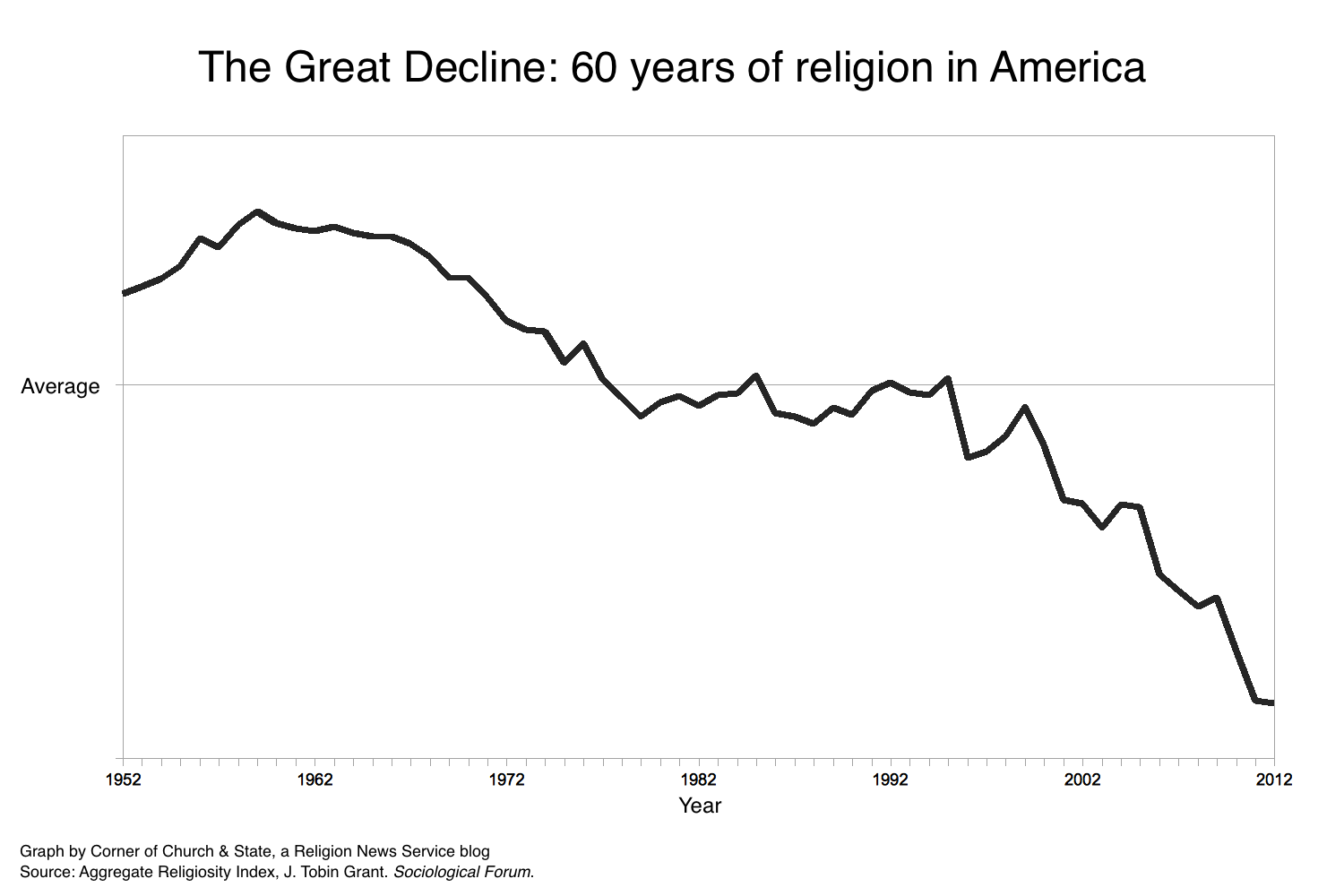

During the 1960, American religious participation and religious affiliation crashed. The Methodists, for instance, lost 5 million members during the 1960s. This 5 million didn't go somewhere else, apparently, and they never returned. Other denominations experienced the same severe losses. The Roman Catholic educational. medical, and social ministries were greatly diminished by professed nuns and monks leaving their orders. What began in the 1960s did not stop. Only the conservative evangelical and fundamentalists denominations have been able to actually increase their membership over the last 45 years. It is likely that they will experience a decline as well, at some point.

Even with these declines, however, religion and religious belief and activity is much higher than in Europe. "The Church" is in no danger of disappearing.

The chart below combines several measures, so there is no left-hand scale.

The Truth will set you free, but it costs money to report it. -

Wayfarer

26.1kYour support for this assertion makes no sense to me. How would a relationship between morality and survival undermine evolution itself? — Metaphysician Undercover

Wayfarer

26.1kYour support for this assertion makes no sense to me. How would a relationship between morality and survival undermine evolution itself? — Metaphysician Undercover

I agree with Noble Dust. It's easy to append the term 'evolution' to everything nowadays, and commonplace to ascribe to 'evolution' what was previously ascribed to 'divine will'. I've been arguing a related argument on this forum all along - that subordinating morality to evolution reduces it to a mere adaption, like a tooth or claw or peacock's tail. There's a very good essay on this called Anything But Human by Richard Polt.

I have no beef with entomology or evolution, but I refuse to admit that they teach me much about ethics. Consider the fact that human action ranges to the extremes. People can perform extraordinary acts of altruism, including kindness toward other species — or they can utterly fail to be altruistic, even toward their own children. So whatever tendencies we may have inherited leave ample room for variation; our choices will determine which end of the spectrum we approach. This is where ethical discourse comes in — not in explaining how we’re “built,” but in deliberating on our own future acts. Should I cheat on this test? Should I give this stranger a ride? Knowing how my selfish and altruistic feelings evolved doesn’t help me decide at all. Most, though not all, moral codes advise me to cultivate altruism. But since the human race has evolved to be capable of a wide range of both selfish and altruistic behavior, there is no reason to say that altruism is superior to selfishness in any biological sense.

Even with these declines, however, religion and religious belief and activity is much higher than in Europe. "The Church" is in no danger of disappearing. — Bitter Crank

There's also the trend towards 'spiritual but not religious' - those who don't attend church but who have a range of beliefs and attitudes, often syncretist (containing ideas from various traditions). One of those Pew forum reports stated that a signficant percentage of self-reported atheists also believe in a higher intelligence - the subtext being, 'just don't call it God!'. -

BC

14.2kThe thing that I dislike about "spiritualism" is that it is too individualized (to suit whatever idiosyncrasies happen to be in play) and it's way too private (related to too individualized).

BC

14.2kThe thing that I dislike about "spiritualism" is that it is too individualized (to suit whatever idiosyncrasies happen to be in play) and it's way too private (related to too individualized).

One individual may return from a long fast in the desert and have a new revelation to report. When people engage in spiritual doodling by themselves, there is rarely revelation or insight. There is no one to challenge the quite likely solipsistic experience of their 'spiritualism'.

I wouldn't say that revelation, a pregnancy of celestial fire, or an anointing by the spirit CAN'T happen by one's self. It just isn't all that likely. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe thing that I dislike about "spiritualism" is that it is too individualized (to suit whatever idiosyncrasies happen to be in play) and it's way too private (related to too individualized). — Bitter Crank

Wayfarer

26.1kThe thing that I dislike about "spiritualism" is that it is too individualized (to suit whatever idiosyncrasies happen to be in play) and it's way too private (related to too individualized). — Bitter Crank

The word 'spiritualism' invariably reminds me of Victorian-era seances.

More to the point, we are nowadays 'individuals' in a manner which wouldn't have been conceivable in bygone days. There was a book by Harold Bloom, Shakespeare and the Invention of the Person, which makes that point very clearly. Whereas in pre-modern culture, there was a lot less room for the individual. But nowadays it's essential, because humans are individualised and expected to be responsible for their own development, in the context of a highly pluralistic and diverse global culture. It's a big part of the predicament of modernity.

That doesn't mean everyone developing a completely idiosyncratic form of spirituality. In Western Buddhist circles, students are constantly encouraged to find a particular centre, teacher or sangha and attend it, so as to avoid wandering up a garden path of their own making. And there are more and less individualistic approaches within those circles. But which one, is always a matter for the individual to decide.

One of the books that influenced me greatly was The Heretical Imperative, by a sociologist, Peter Berger (who was famous for his Social Construction of Reality thesis.)

The main thrust of that argument is that “modernity has plunged religion into a very specific crisis” characterized above all by pluralism. It has done so primarily by forcing men to choose beliefs to which they had previously been consigned by fate. Less and less is dictated by necessity; more and more becomes a matter for questioning. In terms of belief, this means that the faith of one’s fathers must yield to one’s “religious preference.” At the same time, the traditional reasons for choosing one religion over another—or any religion at all—are gravely undermined. By “the heretical imperative” Berger means this radical necessity to choose. “A hareisis originally meant, quite simply, the taking of a choice.” He tries to transfigure the necessity of choice into the virtue of choice as well as to articulate the various possible ways of choosing.

At this point difficulties begin to appear. One does not choose religion as such but a particular religion. Furthermore, it is not clear what the relation is between the utility—if any—of a religion and its truth—if any. Finally, it is not even all that clear what a religion is since everything from Communism to commercialism has been called one. Berger attempts to circumvent such complications by having recourse to the empirical evidence of human experience. He is thus led to define religion as the “human attitude that conceives of the cosmos (including the supernatural) as a sacred order.” 1

Where that chimed with me, was that I had thought of spirituality in terms of the search for spiritual experience. I will admit, many of my early encounters were via hallucinogens - some of those expreriences really did open the 'doors of perception'. The question became, how to get back to that plateau without taking substances, as those experiences were always transient. That's what lead me and millions of others towards Eastern spirituality, which was ostensibly all about 'the experience of the sacred'.

Still working on it. -

BC

14.2kmany of my early encounters were via hallucinogens — Wayfarer

BC

14.2kmany of my early encounters were via hallucinogens — Wayfarer

Harvey Cox, a Baptist, liberation theologist, professor in the Harvard Divinity School, and a fairly adventurous believer (he's a about 87 years old now) tried hallucinogens in a quite proper setting -- out in the desert with a bunch of others, a good sound system, wine, etc. He thought it was a worthwhile experience, but I don't think he repeated it. He also wrote a couple of books about eastern religion -- not as a believer, but in an ecumenical context. [Turning East: Why Americans Look to the Orient for Spirituality-And What That Search Can Mean to the West; Many Mansions: A Christian's Encounter with Other Faiths (1988), (Beacon Press reprint 1992)].

His next to last book was The Future of Faith (2009). Haven't read it, don't know whether I will. I got a great deal out of his earlier books (like The Secular City, 1964) but found some of his later books much less helpful. Anyway, in Future of Faith Cox analyzes the new grassroots Christianity of social activism and the kind of non-institutional spirituality we've been discussing.

Maybe his last book (last year) is/was The Market as God. Here's a link to an excerpt in The Atlantic Magazine

-

Wayfarer

26.1kI also encountered Harvey Cox's writings in my research. That article is terrific, I will read and savour it later. Another of my favourites, although I think even more adventurous than Cox, was Huston Smith, who died on New Years Eve last. I think I already posted some articles and obituaries about him so I won't repeat them. But I think Harvey Cox, Peter Berger, and Max Weber, all have great sociological insights.

Wayfarer

26.1kI also encountered Harvey Cox's writings in my research. That article is terrific, I will read and savour it later. Another of my favourites, although I think even more adventurous than Cox, was Huston Smith, who died on New Years Eve last. I think I already posted some articles and obituaries about him so I won't repeat them. But I think Harvey Cox, Peter Berger, and Max Weber, all have great sociological insights. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI agree with Noble Dust. It's easy to append the term 'evolution' to everything nowadays, and commonplace to ascribe to 'evolution' what was previously ascribed to 'divine will'. I've been arguing a related argument on this forum all along - that subordinating morality to evolution reduces it to a mere adaption, like a tooth or claw or peacock's tail. There's a very good essay on this called Anything But Human by Richard Polt. — Wayfarer

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI agree with Noble Dust. It's easy to append the term 'evolution' to everything nowadays, and commonplace to ascribe to 'evolution' what was previously ascribed to 'divine will'. I've been arguing a related argument on this forum all along - that subordinating morality to evolution reduces it to a mere adaption, like a tooth or claw or peacock's tail. There's a very good essay on this called Anything But Human by Richard Polt. — Wayfarer

So how would you answer my question to Noble Dust then? How would a relationship between morality and survival undermine evolution itself? As I said to Noble, to make such an assertion is one thing. but how would you support it? The passage you quoted indicates that one cannot turn to evolution to answer one's moral questions, but that's not really relevant. What's at issue in my mind is whether we can turn to morality to answer questions about evolution. Can we look at morality as an instance, an example, of evolution? If so, then since the individual's will is paramount in morality, then we'd have to adapt our concept of evolution to allow for the role of the will of the individual. Rather than reducing morality to mere adaptation, we'd have to consider the role of will in adaptation. It is by turning to ourselves, the individual, that we get a true understand of the individual living being. So I believe we must bring this understanding of the individual, derived from understanding oneself, to bear on the role of the individual in the concept of evolution. Then "divine will" is properly understood through an understanding of the individual's will. -

Wayfarer

26.1kHow would a relationship between morality and survival undermine evolution itself? — Metaphysician Undercover

Wayfarer

26.1kHow would a relationship between morality and survival undermine evolution itself? — Metaphysician Undercover

I think evolution is a biological theory. It is about 'how species evolve'. The fact that it has now become a de facto 'theory of everything' is, in my view, a cultural defect and not a philosophy at all. I know evolution occured, in fact sometimes i sense a strong connection with my ancient forbears. But I think trying to combine biological evolution and ethical philosophy is fraught with many problems.

I understand how evolution can be seen as a kind of metaphor for spiritual growth. Sometimes I have thought that Vedic ideas of re-birth and the idea of evolutionary development, could be combined. Tielhard du Chardin and Bergon and others of that ilk talk in those terms. But it's a roundabout way of approaching it, in my view. The overwhelming tendency of evolutionary theory is to depict humanity as 'another species' which is invariably reductive, in my view.

. Can we look at morality as an instance, an example, of evolution? If so, then since the individual's will is paramount in morality, then we'd have to adapt our concept of evolution to allow for the role of the will of the individual. — Metaphysician Undercover

But, it's got nothing to do with evolution, per se. If I wanted to study evolution, I would enroll in biology, to start with, and then study all the requisite disciplines - geology, genetics, and the rest. As I mentioned, that is not what I studied, and I don't see how it's relevant. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI think evolution is a biological theory. It is about 'how species evolve'. The fact that it has now become a de facto 'theory of everything' is, in my view, a cultural defect and not a philosophy at all. I know evolution occured, in fact sometimes i sense a strong connection with my ancient forbears. But I think trying to combine biological evolution and ethical philosophy is fraught with many problems. — Wayfarer

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI think evolution is a biological theory. It is about 'how species evolve'. The fact that it has now become a de facto 'theory of everything' is, in my view, a cultural defect and not a philosophy at all. I know evolution occured, in fact sometimes i sense a strong connection with my ancient forbears. But I think trying to combine biological evolution and ethical philosophy is fraught with many problems. — Wayfarer

We have to face the facts though. We believe in evolution, we know that it occurred. We also know that we are biological beings included within evolutionary theory. So the question is, is it the case that all the properties of living beings are products of evolution, or are there some properties which are special, and are not the products of evolution? Since morality, as a property of living beings, appears to be exclusive to human beings, then how can we account for its coming into being except through evolution? Therefore morality itself cannot be that special property which is not a product of evolution.

But, it's got nothing to do with evolution, per se. If I wanted to study evolution, I would enroll in biology, to start with, and then study all the requisite disciplines - geology, biology, and the rest. As I mentioned, that is not what I studied, and I don't see how it's relevant. — Wayfarer

The point though, is that seeing morality as a product of evolution can give us much better insight into a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between the individual and evolution. And what we can find is that there is something which we might call "the will to act", or something like that, which inheres within every individual living being, as a property of the individual. Now we have found a special property of living beings which appears to transcend evolution. It is not a property of evolution because it is common to all living things. -

Wayfarer

26.1kSince morality, as a property of living beings, appears to be exclusive to human beings, then how can we account for its coming into being except through evolution? Therefore morality itself cannot be that special property which is not a product of evolution. — Metaphysician Undercover

Wayfarer

26.1kSince morality, as a property of living beings, appears to be exclusive to human beings, then how can we account for its coming into being except through evolution? Therefore morality itself cannot be that special property which is not a product of evolution. — Metaphysician Undercover

Well I suppose you're articulating a very big issue there, for many people.

I do fully accept that evolution occured - I have no sympathy for any form of creationism or Protestant 'Intelligent Design'.

But I think, to be candid, my understanding maps pretty closely to 'theistic evolution' - which is the general view of the mainstream Christian denominations (outside the US anyway).

I suppose, to put it in a way that is compatible with the scientific view - when h. sapiens evolved to a certain point, then s/he is no longer determined by purely biological factors. At that point we transcend the merely biological. That, I think, is the real meaning of 'the myth of the fall' - that at the point where humans become self-conscious, self-aware, capable of making judgements of 'good and evil' (the fruit of the tree of good and evil), then at that point moral decisions become necessary, and they're no longer governed by purely biological forces. (I'm sure we have discussed this more than once previously.)

And there are respectable evolutionary biologists who would concur. The biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky, who is famous for the aphorism 'nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution', was also a member of the Orthodox faith, and wrote a book on these very questions, called The Biology of Ultimate Concern (there's a synopsis here). -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI suppose, to put it in a way that is compatible with the scientific view - when h. sapiens evolved to a certain point, then s/he is no longer determined by purely biological factors. At that point we transcend the merely biological. That, I think, is the real meaning of the myth of 'the fall' - that at the point where humans become self-conscious, self-aware, capable of making judgements of 'good and evil' (the fruit of the tree of good and evil), then at that point moral decisions become necessary, and they're no longer governed by purely biological forces. — Wayfarer

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI suppose, to put it in a way that is compatible with the scientific view - when h. sapiens evolved to a certain point, then s/he is no longer determined by purely biological factors. At that point we transcend the merely biological. That, I think, is the real meaning of the myth of 'the fall' - that at the point where humans become self-conscious, self-aware, capable of making judgements of 'good and evil' (the fruit of the tree of good and evil), then at that point moral decisions become necessary, and they're no longer governed by purely biological forces. — Wayfarer

But don't you believe that not just human beings, but all living creatures have a soul, and therefore all these creatures "transcend the merely biological"? If this is the case, then there's no reason to believe that becoming self-conscious, or self-aware, is what allows transcendence of the biological.

I agree that the capacity to judge good and bad is something special which comes about with self-consciousness, and self-awareness, but I think that "the fall" concerns the loss of naivety. It has to do with the feeling of guilt which comes into existence with the capacity to judge one's own act as if it were external to one's self. One can say "I shouldn't have done that" with regards to a particular act. Once we have that capacity, we can know when we've made the wrong choice and proceed to develop a sense of responsibility. Prior to this, the animals lived in a sort of ignorant bliss. They still chose their acts, attempting to reap the rewards, and avoid suffering the consequences, but without the capacity to recognize the acts themselves as good or bad, there was no capacity for guilt. The feeling of guilt comes from realizing I should have done otherwise. And since human beings will always make mistakes we will always be haunted by guilt. -

Wayfarer

26.1kBut don't you believe that not just human beings, but all living creatures have a soul, and therefore all these creatures "transcend the merely biological"? — Metaphysician Undercover

Wayfarer

26.1kBut don't you believe that not just human beings, but all living creatures have a soul, and therefore all these creatures "transcend the merely biological"? — Metaphysician Undercover

No, I don't believe that. I don't believe anyone 'has' a soul. If the word has meaning (and it's an 'if'), it's because it refers to the totality of the being - not simply the mind, personality, physique, but the whole being. That is what I take 'soul' to mean.

The feeling of guilt comes from realizing I should have done otherwise. And since human beings will always make mistakes we will always be haunted by guilt. — Metaphysician Undercover

I'm quite sympathetic to the Christian idea of conscience. From the Catholic Catechism:

"Deep within his conscience man discovers a law which he has not laid upon himself but which he must obey. Its voice, ever calling him to love and to do what is good and to avoid evil, sounds in his heart at the right moment. . . . For man has in his heart a law inscribed by God. . . . His conscience is man's most secret core and his sanctuary. There he is alone with God whose voice echoes in his depths.

Such ideas are generally not much recognises nowadays. -

andrewk

2.1k

andrewk

2.1k

If you mean the idea that conscience is our knowledge of God's law, then I think you're right, and I think the decline of such ideas is a reason for rejoicing.Such ideas are generally not much recognised nowadays. — Wayfarer

On the other hand, if you mean ideas about conscience as our innate feeling of what is right, and our sometimes having internal conflict over what the right thing is, then don't you think that is a perennial theme of fiction, that is as powerful and vibrant today as it ever was? What do you make of Sartre's writings on this, such as the young French man torn over whether to join the resistance or stay and look after his mother? -

Wayfarer

26.1kWhat do you make of Sartre's writings on this, such as the young French man torn over whether to join the resistance or stay and look after his mother? — andrewk

Wayfarer

26.1kWhat do you make of Sartre's writings on this, such as the young French man torn over whether to join the resistance or stay and look after his mother? — andrewk

I admired his pluck in the Resistance, and I also admired him for turning down the Nobel for literature, but overall I detest Sartre. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI think he's over-rated. I struggled with Being and Nothingness as an undergrad but in the decades since I have got to understand him a little better. I think he was honest and authentic in his own terms but I just think his philosophy is barren. Besides you have to smoke Gauloise, drink black coffee and huddle in cafes for Sartre to appeal.

Wayfarer

26.1kI think he's over-rated. I struggled with Being and Nothingness as an undergrad but in the decades since I have got to understand him a little better. I think he was honest and authentic in his own terms but I just think his philosophy is barren. Besides you have to smoke Gauloise, drink black coffee and huddle in cafes for Sartre to appeal. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIf you mean the idea that conscience is our knowledge of God's law, then I think you're right, and I think the decline of such ideas is a reason for rejoicing. — andrewk

Wayfarer

26.1kIf you mean the idea that conscience is our knowledge of God's law, then I think you're right, and I think the decline of such ideas is a reason for rejoicing. — andrewk

As I hope I have made clear in this and other threads, I'm not a Christian apologist, so bear that in mind. But I think the idea of 'conscience', and of there being a real moral or ethical law that it indicates, is real. Where I differ from the Christian interpretation is that I don't believe that only Christians understand that. Ideas such as dharma, logos and Tao, also represent notions of a 'universal order' which is perceptible by 'right seeing'. That is what I think 'conscience' represents.

Sartre, et al, was writing in the shadow of Nietszche's declaration of the 'death of God'. For them, the whole point was the the Universe had been revealed by science to be empty of any intrinsic meaning. That was what a lot of 20th C existentialism was about.

However I think Western culture is entering a post-secular phase, to use Habermas' term. Religions aren't simply going to shrivel up and die in the face of the harsh light of scientific truth. -

Noble Dust

8.1kHow would a relationship between morality and survival undermine evolution itself? — Metaphysician Undercover

Noble Dust

8.1kHow would a relationship between morality and survival undermine evolution itself? — Metaphysician Undercover

To clarify, I said that if morals are a function of evolution, then this would undermine evolution. So not just any relationship, but a relationship of morals being a function of evolution. So, the very concept of evolution that, for instance, you describe, is about change. The assumption you're making, thanks to our fixation on Darwin still, is that "survival" is a constant. You have to realize that this is simply an assumption. There is no reason to assume that this is a constant; it's a baseless assumption. Evolution is change, and yet survival is not subsumed in that change. Why? Why is survival a constant, rather than a function that is subject to the same change? So, to use one's imagination (oh the horror! oh the taboo!), one can see that if evolution involves change, then this also includes the role that survival play(ed) in evolution. To my mind, it's a simple, obvious thing. More to come tomorrow; I'm exhausted after an over-long night at work. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kTo clarify, I said that if morals are a function of evolution, then this would undermine evolution. So not just any relationship, but a relationship of morals being a function of evolution. — Noble Dust

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kTo clarify, I said that if morals are a function of evolution, then this would undermine evolution. So not just any relationship, but a relationship of morals being a function of evolution. — Noble Dust

I must admit, I had difficulty with this, and had to reread numerous times, because "function of" may be taken in numerous ways. I never did resolve the question of what you actually meant. If I look at evolution as a real physical occurrence, then "a function of evolution" would imply that evolution plays a part, a purpose, in a larger role. Morality then, if it were a function of evolution, would be this larger role. But this is inverse from what I meant, what I meant is that evolution would be a function of morality, morality playing the part of the function, in the larger role, evolution. So I'm talking about evolution being a function of morals, morality having the function, of influencing evolution in particular ways.

The assumption you're making, thanks to our fixation on Darwin still, is that "survival" is a constant. — Noble Dust

Clearly I'm not assuming survival as a constant. I'm dealing with the individual, and the individual does not survive in evolution. In fact the death of the individual, to be replaced by others which are different is essential to evolution. Furthermore, extinction of certain species is inherent within evolution, so I do not see how survival could be a constant. What we might see as a constant, is the will to survive, or the desire to survive, which is held by the individual, But natural forces always confound this will to survive, as each and every individual is fated to death.

Why is survival a constant, rather than a function that is subject to the same change? — Noble Dust

Again, I have great difficulty with your use of "function" here. If evolution were for the purpose of survival, then evolution would be a function (having the purpose) of survival. This is a possibility, that since we cannot, as individuals, survive, life as a whole evolves, and survives. But it would make no sense to say that survival is a function of, or has the purpose of, evolution, because no individuals survive, so it is impossible that survival could be a given, which serves as a function toward some larger role.

No, I don't believe that. I don't believe anyone 'has' a soul. If the word has meaning (and it's an 'if'), it's because it refers to the totality of the being - not simply the mind, personality, physique, but the whole being. That is what I take 'soul' to mean. — Wayfarer

So you disavow these dualist principles? The body and soul are necessarily a unity, and there is no possibility of separation, not even in principle? Do you realize that this is contrary to the fundamentals of most religions? -

Noble Dust

8.1kI must admit, I had difficulty with this, and had to reread numerous times, because "function of" may be taken in numerous ways. — Metaphysician Undercover

Noble Dust

8.1kI must admit, I had difficulty with this, and had to reread numerous times, because "function of" may be taken in numerous ways. — Metaphysician Undercover

Not to be lazy, but I was basically trying to make the argument (apparently not very well) that Wayfarer illustrated when he said:

subordinating morality to evolution reduces it to a mere adaption, like a tooth or claw or peacock's tail — Wayfarer

And then, taking it a step further, I was suggesting that maybe morality and survival are stages, if you will, along the course of evolution. It's an idea that I'm toying with, that I haven't fleshed out. Basically, morality supersedes survival in the evolutionary process. Maybe with other steps in between, maybe not. I hope that at least makes more sense?

I'm not a very discursive thinker, so I seem to have trouble communicating my ideas to people like you who have a much stronger command of reason and logic. What I'm seeing is this: there is a tendency to try to understand morality through the lens of evolutionary survival. I think that's incorrect. I see this more in the general population, not necessarily in a philosophical realm as much (other than the new atheists, although they're of course not actual philosophers). And I think this is actually an important distinction; it seems like folks like Wayfarer and I on here have a tendency to make observations based on what we see in the population at large, rather than simply marshaling the forces of one's own ideas against the forces of another. This seems like an approach not always taken by others here. Simply an observation, for the sake of trying to understand one another better.

Clearly I'm not assuming survival as a constant. — Metaphysician Undercover

I shouldn't have assumed this. But it's certainly something I see from others. But, what do you see as the purpose of evolution? Is there a telos? If not, then who cares? What's the point? -

Wayfarer

26.1kAnd then, taking it a step further, I was suggesting that maybe morality and survival are stages, if you will, along the course of evolution. It's an idea that I'm toying with, that I haven't fleshed out. Basically, morality supersedes survival in the evolutionary process. Maybe with other steps in between, maybe not. I hope that at least makes more sense?

Wayfarer

26.1kAnd then, taking it a step further, I was suggesting that maybe morality and survival are stages, if you will, along the course of evolution. It's an idea that I'm toying with, that I haven't fleshed out. Basically, morality supersedes survival in the evolutionary process. Maybe with other steps in between, maybe not. I hope that at least makes more sense?

I'm not a very discursive thinker, so I seem to have trouble communicating my ideas to people like you who have a much stronger command of reason and logic — Noble Dust

Not at all, I think you're a very clear thinker and one whom I often tend to agree with.

With regards to the point - have a look at Alfred Russel Wallace's Darwinism Applied to Man. It's couched in rather Victorian language, for obvious reasons. Wallace became increasingly drawn to Victorian spiritualism and non-orthodox religious ideas and as a consequence much of what he says in this genre is nowadays disregarded. But I'm sure you'll find it interesting - he makes a similar point.

My view, as I explained earlier, is that morality comes into being with self-awareness, and also tool-use, language, and ownership. That gives rise to a sense of what is mine, what is self, what is other than me, what can be lost, from which arises the fundamental bases of morality - what I might do, or should do, what are the consequences of that, and so on. I believe h. sapiens evolved to the point where that becomes possible. But, when it is possible, then at that point one is no longer determined by the purely biological. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kAnd then, taking it a step further, I was suggesting that maybe morality and survival are stages, if you will, along the course of evolution. It's an idea that I'm toying with, that I haven't fleshed out. Basically, morality supersedes survival in the evolutionary process. Maybe with other steps in between, maybe not. I hope that at least makes more sense? — Noble Dust

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kAnd then, taking it a step further, I was suggesting that maybe morality and survival are stages, if you will, along the course of evolution. It's an idea that I'm toying with, that I haven't fleshed out. Basically, morality supersedes survival in the evolutionary process. Maybe with other steps in between, maybe not. I hope that at least makes more sense? — Noble Dust

How could it makes sense that morality could supersede survival? Since we all die, and there is a possibility that life may be eradicated from earth, we haven't yet achieved survival. If we instil morality as the goal or purpose, then how can we ensure that this morality would produce survival? If there are beings which are living, and they do not have morality, then doesn't this indicate to you that survival is of a higher priority than morality? In relation to being in general, don't you think that to be alive is of a higher priority than to be moral. Morality exists as a hierarchy of values, as Aristotle says, one thing is for the sake of another, which is for the sake of something further, etc., until we reach the highest good. But morality is the means by which we reach the good, it relates to the actions, the means to the end, it isn't the good which is sought. So morality must be for the sake of some higher good.

What I'm seeing is this: there is a tendency to try to understand morality through the lens of evolutionary survival. I think that's incorrect. I see this more in the general population, not necessarily in a philosophical realm as much (other than the new atheists, although they're of course not actual philosophers). — Noble Dust

I see evolution through the lens of morality, so my thinking is somewhat different from the general population. Notice that we all think in a different way, you, me Wayfarer, and others, yet we always seem assume that there is a way of the general population. The differences are what makes us individuals, yet we always assume that there is something which unites us as "the same". We take this for granted, that we are of the same species, that we follow the same cultural norms, but how do we really justify this? Within the same species, there are different cultures. Within the same culture, people think in different ways. Isn't there a reason why we try to be like others?

I shouldn't have assumed this. But it's certainly something I see from others. But, what do you see as the purpose of evolution? Is there a telos? If not, then who cares? What's the point? — Noble Dust

Come on Dusty, how can you ask me what's the purpose of evolution? Isn't this like asking for the meaning of life? Don't you think that survival is very important? If you want to supersede survival, as the purpose of evolution, then you need to determine the purpose of survival. That's not an easy question. -

Noble Dust

8.1kHow could it makes sense that morality could supersede survival? Since we all die, and there is a possibility that life may be eradicated from earth, we haven't yet achieved survival. — Metaphysician Undercover

Noble Dust

8.1kHow could it makes sense that morality could supersede survival? Since we all die, and there is a possibility that life may be eradicated from earth, we haven't yet achieved survival. — Metaphysician Undercover

Because of the possibility of life after death. Or, the possibility of death eventually being overcome. I also don't think my own survival is my ultimate goal. Even something like suicide rates should be enough to at least suggest the possibility that for us humans, things are different. We've evolved past a pure physical state; we've become so complex that there's a type of sickness that for us is worse than life, than survival itself. We want more than survival on an individual level. When we don't achieve this "more than" state, some of us begin to "go off" if you will, and begin down a road that leads us to a point where we'd rather freely end our own survival. An animal will fight for it's life until it's dying breath, but a human person may freely decide to end their own life.

Also, it sounds like you're equating "survival" with something like "ultimate survival" here. Of course we've "achieved survival". We still exist as a species. We achieve survival every day.

If we instil morality as the goal or purpose, then how can we ensure that this morality would produce survival? — Metaphysician Undercover

I wasn't suggesting morality to be the purpose of evolution. I realize that wasn't clear. I agree with you that morality is the means by which we reach the highest good. Or at least, I agree with the idea that morality is a vehicle, or a structure. I realize I've been framing this discussion in my mind within the ideas of Teilhard de Chardin. I don't necessarily buy his ideas, but I'm fascinated by them, and I toy with them sometimes. So, I can imagine the structure of physical evolution giving birth to consciousness, which is almost a sixth sense. With the birth of consciousness comes a new structure: morality. At the least, this makes more sense to me than the idea of morality existing "eternally", or just in some vague abstract sense that's not related to time or physical matter. So in this sense, I can entertain the possibility of the evolution of moral concepts, or the evolution of a moral structure within consciousness in general. But I again appeal to the difference between knowledge and practice here. I don't even necessarily claim this idea as my own opinion. I'm working through possibilities. This is what I mean by not thinking discursively; I'd rather work through ideas intuitively and non-linearly. This seems to be problematic for people.

In relation to being in general, don't you think that to be alive is of a higher priority than to be moral. Morality exists as a hierarchy of values, as Aristotle says, one thing is for the sake of another, which is for the sake of something further, etc., until we reach the highest good. But morality is the means by which we reach the good, it relates to the actions, the means to the end, it isn't the good which is sought. So morality must be for the sake of some higher good. — Metaphysician Undercover

So do you consider survival more important than achieving the highest good?

I don't think being alive is a higher priority than being moral. See my earlier comments about suicide. Life can be agony. If being alive is a higher priority than being moral, then I'm free to kill anyone who threatens my life. Sounds like moral evolution, right? Wait...

Notice that we all think in a different way, you, me Wayfarer, and others, yet we always seem assume that there is a way of the general population. — Metaphysician Undercover

We're the strange type who post on philosophy forums. I don't mean this in a holier-than-thou sense, but there is definitely a trend within the general population to accept a general consensus without using critical thinking to question the consensus. Folks like us tend to go the opposite direction. So there's no need to use people like us as a counter-example to the idea that the general population follows trends.

The differences are what makes us individuals, yet we always assume that there is something which unites us as "the same". We take this for granted, that we are of the same species, that we follow the same cultural norms, but how do we really justify this? Within the same species, there are different cultures. Within the same culture, people think in different ways. Isn't there a reason why we try to be like others? — Metaphysician Undercover

Is this a continuation of the argument you start at the beginning of that paragraph? I can't really tell; it doesn't make much sense to me in relation to what you initially said. For instance, you seem to be conflating being "of the same species" with "following[ing] the same cultural norms". But then almost immediately you say "Within the same species, there are different cultures."

how can you ask me what's the purpose of evolution? — Metaphysician Undercover

How can you not ask yourself that question?

Don't you think that survival is very important? — Metaphysician Undercover

It's important in the same way that a car engine is important. It gets me from A to B. But it's not the purpose of my trip. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kBecause of the possibility of life after death. — Noble Dust

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kBecause of the possibility of life after death. — Noble Dust

Life after death is contradictory, unless we remove the individuality of living. We can consistently say that life itself continues after an individual dies, so there is life after death, but this doesn't hold up to rigorous logic because it is a category error. In one case, "life" is the property of particulars, individual beings, and in the other, it is a generalization, life in general continues. If we remove the individual, to say that life continues, then we don't have any real grounding for the concept of "life", because we get a nonsense notion of life, without an individual being which is living. It's very difficult to make sense of "life" without that individual being which is living.

So all the ancient traditions, such as the myths recounted by Plato, portray individual souls in the post-death condition. At that time, way back then, and to this day now, our minds have not been able to grasp this generality of life, separate from the particulars, so there has been no portrayal of life in general, persisting after the death of the individual. In all these ancient myths, we always encounter individual souls. This implies that life is somehow bound to the particular, that individuality is an essential aspect of living. We tend to assign individuality to the material body, saying that it is the properties of the material body which make us different from each other. But then when we try to abstract the soul from the material body, i.e., the soul leaves the body at death, we have no way to dissolve the individuality of the soul, and individuality does not get lost in the abstraction. Therefore, individuality is what is essential to the soul. If we follow this into mysticism, that individuality becomes a Oneness, a Unity. But this mysticism breaks the logic, the individual souls are lost into the One, the Soul, and there are no logical principles for this. Just because the individual is a single unity, a particular, or one, this does not justify a One, in the sense of an abstract unity.

The individuality of the resurrected human being is an important issue in Christianity. I believe it was Paul who argued strongly, in the early years of Christianity, that the individuality of "the person" is maintained in resurrection. This is important because it's contrary to the mystical platform of One Soul. But the Christian position opens up a whole new problem, and that is the continuity of existence of the individual. In the ancient myths, there was a necessary continuity of existence of the soul, after the death of the body. When the body dies, the soul must keep living, so it has to go somewhere. The Christians seem to allow a break in the continuity. We die, then later there is a judgment, when we are brought back in resurrection. Now there's a temporal gap which may be filled with the concept of purgatory. If we don't opt for that concept of purgatory, we have to account for this discontinuity. How can the individual soul stop existing for a time, then come back later for an eternal existence? What constitutes this break in existence? What kind of existence does the soul have in this break period? As an analogy, consider a seed, or a spore. Those things can go into a suspended animation for an extended period of time, when they are not living, but then when the conditions are right, they spring into life? What supports this capacity for discontinuity which life demonstrates?

Also, it sounds like you're equating "survival" with something like "ultimate survival" here. Of course we've "achieved survival". We still exist as a species. We achieve survival every day. — Noble Dust

This is the category error which I was trying to point out. A species is not a living being. It doesn't make sense to say that the species exists as a thing, because it is not a living being, it is an abstraction. So the same error follows if we say that the species "survives". If we bring "survive" into the proper category, we have to refer to ourselves. Yes, it surely makes sense to say, of course we've survived, I'm here today, and you're here today. You and I have survived. But of what import is that survival when we could both be gone tomorrow, and our own lives are but a flash in the pan anyway? To have survived is not the same thing as to survive. We can give "survival" a more important meaning, by making it a goal, a purpose, to survive after that break in continuity, described above.

So do you consider survival more important than achieving the highest good? — Noble Dust

I haven't yet seen good support for your separation between "survival" and "highest good". To me, I see no reason yet why survival should not be the highest good. You keep trying to drive a wedge between these two, but it seems like a wedge of categorical separation, such that "survival" is something which a species does, while morality is something which individuals do. When you put these both in the same category, then I see no reason why survival of the individual (which includes the above discussed "life after death"), should not be the highest good.

Is this a continuation of the argument you start at the beginning of that paragraph? I can't really tell; it doesn't make much sense to me in relation to what you initially said. For instance, you seem to be conflating being "of the same species" with "following[ing] the same cultural norms". But then almost immediately you say "Within the same species, there are different cultures." — Noble Dust

The point I was trying to make is that "species", and "norms" are of the same category, and that is abstractions, they are concepts. There is no such particular, individual, existing thing as the norms of a culture, nor is there any such particular individual existing thing as a species. These are concepts, abstractions. As they are both ways of comparing individuals with respect to certain properties, and establishing principles of commonality, I see no reason why we can't make a valid comparison between the two. Why do you keep insisting on denying such a comparison?

It's important in the same way that a car engine is important. It gets me from A to B. But it's not the purpose of my trip. — Noble Dust

You don't seem to appreciate the true meaning of "survive". You put survival into the past, to say "I have survived, therefore I have fulfilled my desire to survive". I have made it to point B, therefore if getting to point B was my goal, I no longer have a goal. But this is what "survived" means, it is not what "survive" means. Survival is an ongoing, continuity. It does not end with a conquest of survival, it continues onward indefinitely. If survival ended in such a conquest then there would be no more survival afterwards, and it would negate itself at that point of conquest.

You seem to believe that there is something more important to your life than actually living. What could that possibly be? Being alive is necessary for you to do anything, so how could anything be more important than this? Therefore being alive (and hence survival) is of the highest importance, because anything else which you might do, including being moral, is dependent on this, being alive. -

Noble Dust

8.1kLife after death is contradictory, unless we remove the individuality of living. — Metaphysician Undercover

Noble Dust

8.1kLife after death is contradictory, unless we remove the individuality of living. — Metaphysician Undercover

Paradoxes are an important purveyor of truth. Experience here is key; I haven't experienced death and whatever may or may not come after it, so I'd rather retain the simplicity of a child; I'll trust to the possibility of something coming after. But simply just the possibility, not any certainty. I'll strive to seek the purity of heart that wills one thing, along with Kierkegaard.

If we remove the individual, to say that life continues, then we don't have any real grounding for the concept of "life", because we get a nonsense notion of life, without an individual being which is living. — Metaphysician Undercover

No, it's not a nonsense notion of life, it's a notion that acknowledges Not-Knowledge, that acknowledges Un-knowing. It's a notion that acknowledges faith (ultimate concern, via Tillich), as one of the primary functions of how we interface with life. It's a letting go of the need to know.

This is the category error which I was trying to point out. A species is not a living being. It doesn't make sense to say that the species exists as a thing, because it is not a living being, it is an abstraction. — Metaphysician Undercover

Surely the survival of a species as a whole is not hard to conceptualize. Seriously...

I haven't yet seen good support for your separation between "survival" and "highest good". To me, I see no reason yet why survival should not be the highest good. — Metaphysician Undercover

I can't even parse through the confusing misapplication of terms here. And I've already made my point earlier about this distinction. If survival is the highest good, than an almost comically ironic solipsism is the only way forward. Because, as you say, you only equate survival to the individual. So if survival (the highest good) is only about me, then my "good" is, in truth, the only good that exists. So it's you versus me. Given the last slice of bread left on the planet, it's fair game for me to grotesquely murder you for the sake of my own survival, since survival is the highest good (but only my personal survival, since the survival of the species is not a real thing). And you never addressed my points about suicide. Feel free to vehemently disagree, or whatever. But at least address my points about suicide in relation to this debate instead of attempting to only hit me at whatever weaker points you might perceive to exist in my argument.

There is no such particular, individual, existing thing as the norms of a culture, nor is there any such particular individual existing thing as a species. These are concepts, abstractions. — Metaphysician Undercover

So all abstractions are not real then, logically? Surely you agree.

You don't seem to appreciate the true meaning of "survive". You put survival into the past, to say "I have survived, therefore I have fulfilled my desire to survive". — Metaphysician Undercover

You misunderstand my analogy (and analogies are imperfect, as this one surely is). When I say that survival gets me from point A to B, I mean that survival moves me along the path of my life. It's only one of the things that does so. It's surely an important driving factor. But, the analogy could be said instead like this: survival is a mechanism of life. It doesn't describe why life exists. the mechanics of the car engine don't tell me why someone might find it beneficial to use a car. Surely this is easy to understand?? -

Wayfarer

26.1kLife after death is contradictory, unless we remove the individuality of living. — Metaphysician Undercover

Wayfarer

26.1kLife after death is contradictory, unless we remove the individuality of living. — Metaphysician Undercover

I think the underlying truth of the higher religions is the quest to realise an identity that is not subject to death.

I think what Noble Dust is getting at, is that there may be a conception of life, within which virtue is of a higher importance than whether one lives or dies. And I can think of no better illustration of the idea than the Death of Socrates, from the Apology. The detachment shown by Socrates at the approach of his own death, indicates that he at least believes that the death of the body is of minor consequence compared to the overall state of his soul.

You seem to believe that there is something more important to your life than actually living. What could that possibly be? Being alive is necessary for you to do anything, so how could anything be more important than this? Therefore being alive (and hence survival) is of the highest importance, because anything else which you might do, including being moral, is dependent on this, being alive. — Metaphysician Undercover

Again, in the traditional understanding, there are many circumstances in which death is a lesser evil than dishonour. If, for example, one had to commit some monstrous evil in order to preserve one's own life, then, given that the fate of the soul depended on the actions, it would be preferable to die than to commit such an act.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum