-

creativesoul

12.2kThe belief under our consideration is problematic for the conventional rendering of belief as a propositional attitude. It is not problematic for rendering it in propositional form — creativesoul

Jack believed that a broken clock was working.

So, Banno, I'm wondering what you think of this? It seems to be not at all problematic for being rendered in propositional form, but Jack never believes the statement is true. Do you not find that both odd and interesting? -

Janus

17.9kNo, I have acknowledged there is a sense in which we can say that. But the content of his belief is not that a broken clock is working. That's all I've been pointing out.

Janus

17.9kNo, I have acknowledged there is a sense in which we can say that. But the content of his belief is not that a broken clock is working. That's all I've been pointing out. -

creativesoul

12.2k

We're in agreement there. I've never argued otherwise.

The content of belief is what the debate is about.

Jack believes(or believed) that a broken clock is(was) working. So, what is that belief about, and what is the content of that belief? -

Banno

30.6kJack believed that a broken clock was working. — creativesoul

Banno

30.6kJack believed that a broken clock was working. — creativesoul

Is there a point? I don't understand how it is that you don't understand.

(Jack believed that a broken clock was working) is ambiguous.

Is (the clock is broken) within the scope of Jack's belief? Then you have Jack believed that: ((The clock is broken) & (the clock is working)); Poor old Jack needs help.

Or is it outside the scope? Then you have: The clock is broken and (Jack believed that: (the clock is working))

No problem. In both cases the belief is presented as a propositional attitude. -

Olivier5

6.2k“a broken clock was working and we once believed it” ? — neomac

Olivier5

6.2k“a broken clock was working and we once believed it” ? — neomac

By definition, a broken clock doesn't work, so your proposition makes no sense. A proposition equivalent to "it was raining and we thought otherwise," would be more like: "the clock was broken but we didn't know it, and we wrongly assumed it was working." -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

, but only after you learned that is what the scribbles are labeled as. I've been using the term scribble, not word, because they are scribbles without rules and words when rules are applied to scribbles.Yep, this is correct if we take strings of characters, independently from any pre-defined linguistic codification. The difference is that with words (notice that the term “word” is already framing its referent, like an image, as a linguistic entity!) — neomac

Isn't it a seven of diamonds regardless of what card game that we are playing? We don't even need a game to define the image as a seven of diamonds, because we have rules about what scribble refers to which shapes (diamonds, spades, hearts, or clubs).You can have all kinds of sets of rules (e.g. the codification of traffic signs). Concerning the problem at hand, one thing that really matters is to understand if/what systems of visual codifications disambiguate an image always wrt a specific proposition: think about the codified images of a deck of cards. Does e.g. the following card have a propositional content that card game rules can help us identify? What would this be? — neomac

In your example of street signs, we have signs with no words, and yet they are properly interpreted by most people as to what they are saying. The rules we establish are arbitrary and we have to spend time learning what some symbol (imagery, audible, etc.,) refers to. The rules themselves are language-less as each individual has their own unique experiences, starting from a pre-language (pre-symbol-using) state, in learning how the symbols are used to refer to what, or was, or potentially is the case. -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Lame. Wtf does it mean to be neutral on a question, if not "I don't want to answer it because the answer would contradict other things that I've said."?First of all, I'm neutral on the question. I'm just exploring the implications.

I'm starting with the assumption that my beliefs are limited by the limits of my language.

Why some fucker would assert that is a different topic. Maybe we could start a thread:

Why do some fuckers believe the limits of their languages are the limits of their worlds? — frank

You're starting with an incoherent assumption. You need to define "language" and in a way that acknowledges that there are languages that we don't know and some that we do, and what the noticeable (visual) difference is.

So you can assert something, but when the assertion is questioned we need to start another thread? The ways in which people on this forum try to avoid answering valid questions grows stranger by the day.Why some fucker would assert that is a different topic. Maybe we could start a thread:

Why do some fuckers believe the limits of their languages are the limits of their worlds? — frank

Wait, I thought we were suppose to start another thread on this topic?If someone says "the limits of my language mean the limits of my world" is this assertion self contradictory?

What is the pov of the assertion? I'm asking you because you're mentally flexible. You could probably see it better than me. — frank

I don't say such things, you are, so it is incumbent upon you to explain what you mean, because I have no idea.

The question I asked above is much simpler and can move us forward in our conversation, yet you'd rather waste time trying to interpret some nonsensical string of scribbles. -

frank

18.9kThe question I asked above is much simpler and can move us forward in our conversation, yet you'd rather waste time trying to interpret some nonsensical string of scribbles. — Harry Hindu

frank

18.9kThe question I asked above is much simpler and can move us forward in our conversation, yet you'd rather waste time trying to interpret some nonsensical string of scribbles. — Harry Hindu

What question? -

Harry Hindu

5.9kWhat does a language that you don't know look like? And when describing what a language you know looks like, are you describing the language or your knowledge of the language? — Harry Hindu

Harry Hindu

5.9kWhat does a language that you don't know look like? And when describing what a language you know looks like, are you describing the language or your knowledge of the language? — Harry Hindu -

neomac

1.6k

neomac

1.6k

> Rather than propose something I've not,

Oh really? This is what you wrote: “Can Jack look at a broken clock? Surely. Can Jack believe what the clock says? Surely. Why then, can he not believe that a broken clock is working?”.

To obtain “Jack believes that broken clock was working” you simply replaced the term “broken clock” from “Jack looks at a broken clock” with the term “the clock” from “Jack believe what the clock says”. This is a substitution operation applied to two propositions (one reporting a belief ascription), to obtain a third proposition (reporting a belief ascription) based on the sheer co-reference of some terms involved. That is why I call it propositional calculus. Indeed a propositional calculus that is supposed to work independently from any other pragmatic and contextual considerations. Hence: you proposed something by applying some propositional calculus that I find quite preposterous.

Since you didn’t perceive how preposterous your argumentative approach is, then I gave you another case where your type of reasoning (i.e. propositional calculus applied to belief ascriptions, based on sheer co-reference, and indifferent to any pragmatic/contextual considerations) looks more evidently preposterous: if one can render “S did/did not believed that p” as “p and S did/did not believe it” and vice versa, and one can take p="that broken clock was working”, why can’t I justifiably render “Jack did believe that broken clock was working” as “that broken clock was working and Jack did believe it”?

> would it not just be easier to answer the question following from the simple understanding set out with common language use?

That’s what I and others did, unless you think you are a more competent speaker than all of those who objected your rendering, you should take this as a linguistic datum and infer that your account is not that common language usage, after all. And indeed you did that already when you claimed to be questioning the “conventional” belief account.

Let me repeat once more: I don’t feel intellectually compelled to answer questions based on preposterous assumptions, like this one:“Can Jack look at a broken clock? Surely. Can Jack believe what the clock says? Surely. Why then, can he not believe that a broken clock is working?”. But I can certainly show you why I find them preposterous (which I did). BTW, as far as I read from your posts [1], this is the only argument you made to justify your belief ascription rendering (besides your thought experiment with a fictional character that — surprise surprise — agrees with you!).

Anyways, I now question this justification not simply because its conclusion is wrong (which is), but also because itself is flawed by design (even if your conclusion was correct)!

> Do you not find it odd that Jack would agree, if and when he figured out that the clock was broken?

Seriously?! By “Jack” you mean a fictional character in a story that you just invented? Oh no, that’s not odd at all, it would be indeed much more odd if you invented stories where fictional characters explicitly contradict your theories, and despite that you used those stories to prove your theory.

OK let me help you with your case. Indeed, I think there might be a way out for you but only if you reject this line of reasoning: “Can Jack look at a broken clock? Surely. Can Jack believe what the clock says? Surely. Why then, can he not believe that a broken clock is working?” (along with the idea that de re belief ascriptions are appropriate independently from pragmatic and contextual considerations, or a better rendering than de dicto belief ascriptions). Indeed if you rejected that line of reasoning, then you could explain the situation in your thought experiment based on pragmatic considerations and shared assumptions, much better. How? Here you go: since at moment t2, you and Jack share the same assumptions about the reliability of that clock, the belief of Jack about that clock at t1, and the rationality of you and Jack, then between you two it would be easier to disambiguate the claim “Jack believed that broken clock was working”, and this is why you two would not find it so problematic to use that belief ascription (BTW that is also why we can't exclude a non-literal or ironic reading of this belief ascription either). However, as soon as we add to the story another interlocutor who doesn’t share all the same assumptions relevant to disambiguate “Jack believed that broken clock was working” then this rendering would be again inappropriate or less appropriate than de dicto rendering “Jack believed that clock was working”.

> Interesting thing here to me is that on the one hand you're railing against propositional calculus(as you call it), and yet again on the other your unknowingly objecting based upon the fact that Jack would not assent to his own belief if it were put into propositional form and he was asked if he believed the statement. At least, not while he still believed it.

There are 2 problems in your comment:

- It can be misleading to claim that I’m “railing against propositional calculus”. I’m more precisely railing about the propositional calculus you applied to belief ascription rendering in order to justify the claim that “Jack believes that broken clock is working” is not only fine independently from any pragmatic and contextual considerations, but even better than the de dicto rendering “Jack believes that clock is working”.

- I didn’t make the claim you denounce here “your unknowingly objecting based upon the fact that Jack would not assent to his own belief if it were put into propositional form and he was asked if he believed the statement.” (ironically, you were the one repeatedly suggesting me to stick to what you write), nor my line of reasoning requires the claim “Jack would not assent to his own belief if it were put into propositional form and he was asked if he believed the statement. At least, not while he still believed it.” to be true, independently from pragmatic and contextual considerations (see the way out I suggested you previously).

[1] If you have others and can provide links, I’d like to read them. -

neomac

1.6kBy definition, a broken clock doesn't work, so your proposition makes no sense. — Olivier5

neomac

1.6kBy definition, a broken clock doesn't work, so your proposition makes no sense. — Olivier5

Of course, but if you follow my exchange with Creative Soul with due attention, you should understand why I made it up. That crazy sentence is the result of some unjustified propositional calculus that I applied to the belief ascription rendering "Jack believes that broken clock is working" (proposed by CreativeSoul). Why did I do that? To show CreativeSoul that my unjustified propositional calculus is very much the same type of propositional calculus CreativeSoul used to justify his belief ascription rendering (e.g. "Jack believes that broken clock is working") -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

We're still on this? CS doesn't yet realize that the proposition, "Jack believed that a broken clock was working." isn't something Jack is saying (believing), but what someone else is saying (believing) about Jack and the clock? Who is making this statement? It certainly can't be Jack.Jack believed that a broken clock was working.

— creativesoul

Is there a point? I don't understand how it is that you don't understand.

(Jack believed that a broken clock was working) is ambiguous.

Is (the clock is broken) within the scope of Jack's belief? Then you have Jack believed that: ((The clock is broken) & (the clock is working)); Poor old Jack needs help.

Or is it outside the scope? Then you have: The clock is broken and (Jack believed that: (the clock is working))

No problem. In both cases the belief is presented as a propositional attitude. — Banno -

frank

18.9k

frank

18.9k

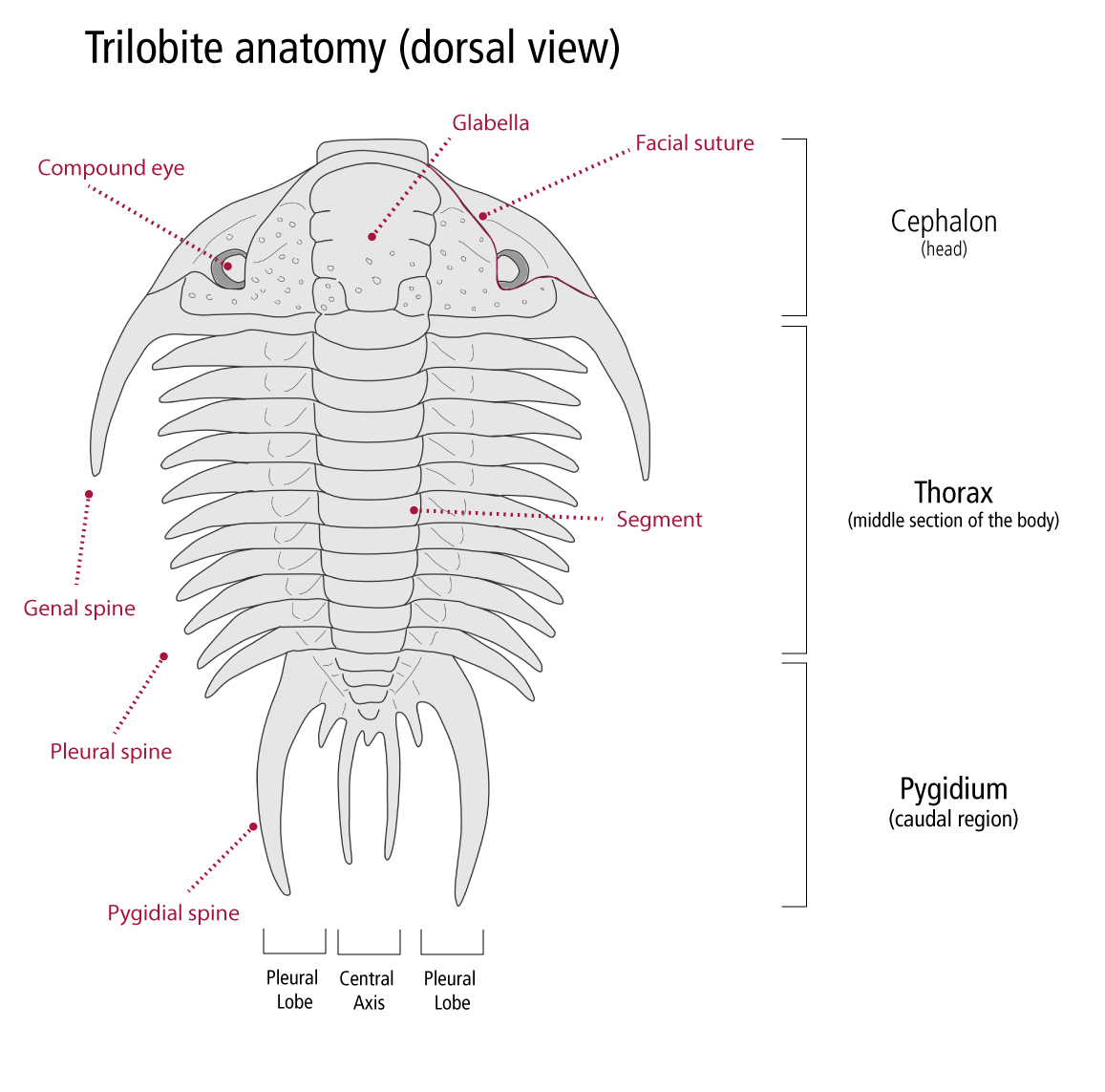

But what about this?

The only good trilobite is a dead trilobite as far as I'm concerned. -

neomac

1.6kbut only after you learned that is what the scribbles are labeled as. I've been using the term scribble, not word, because they are scribbles without rules and words when rules are applied to scribbles. — Harry Hindu

neomac

1.6kbut only after you learned that is what the scribbles are labeled as. I've been using the term scribble, not word, because they are scribbles without rules and words when rules are applied to scribbles. — Harry Hindu

Agreed, indeed I was backing up the part where you wrote “meaning that words (as an image of strings of scribbles)”

Isn't it a seven of diamonds regardless of what card game that we are playing? We don't even need a game to define the image as a seven of diamonds, because we have rules about what scribble refers to which shapes (diamonds, spades, hearts, or clubs). — Harry Hindu

Maybe regardless of any specific card game, but the challenge here is to express the propositional content of that image (something that an image can share with sentences, different propositional attitudes, different languages): so is the propositional content of that image rendered by “this is a seven of diamonds” or “this is a seven of diamonds in standard 52-card deck” or “this is a card of diamonds different from a 1 to 6 or 8 to 13 of diamonds” or “this is a seven of a suit different from clubs, hearts, spades” or “this is a card with seven red diamond-shaped figures and red shaped number seven arranged so and so” or any combination of these propositions? All of them are different propositions which one is the right one? BTW “this” is an indexical, and shouldn’t be part of the content of an unambiguous proposition: so maybe the propositional content is “something is a seven of diamonds” or “some image is a seven of diamonds”? And so on.

At least this is how I understand the philosophical task of proving that images have propositional content, but I'm neither sure that others understand this philosophical task in the same way I just drafted, nor that this task can be accomplished successfully. -

creativesoul

12.2k

We're all stubborn around here. :smile:

I understand that and most of what others are objecting to. The rendering of the belief as (a broken clock is working) is said to be problematic. On my end, it would be better put as (that broken clock is working), but the objections would remain. What I do not understand is the move to set (that broken clock) outside of the scope of Jack's belief and replace it with (that clock) when the example hinges upon the fact that the clock is broken but Jack believes what it says. Jack does not know it is broken, so he cannot believe that it is broken. I grant that much entirely, but there's no reason to say that he cannot believe that that broken clock is working. -

creativesoul

12.2k

I'm going to postpone any further replies to you for now. You seem to be taking things personally. Mea culpa on a few of those things you said in the last long reply... -

creativesoul

12.2k

The example is akin to believing that a facade is a barn, or a sheet is a sheep. These could all be broken down into two propositions as Moore did with (it is raining and I do not believe it). -

neomac

1.6k

neomac

1.6k

Fine with me, I don’t want to waste your time and energies. And you already have many other interlocutors. In any case, I'm more playful than you might think. Just I can play it tougher depending on other peoples' replies. -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

The move to set it outside the scope of Jack's belief is due to the fact that it would be impossible for Jack to make such a statement based on his belief. It would be what someone else is stating about their own beliefs about Jack and the clock. After all, Jack could be tricking the observer (his boss) into thinking he doesn't really know what time it was as an excuse for being late.What I do not understand is the move to set (that broken clock) outside of the scope of Jack's belief and replace it with (that clock) when the example hinges upon the fact that the clock is broken but Jack believes what it says. Jack does not know it is broken, so he cannot believe that it is broken. I grant that much entirely, but there's no reason to say that he cannot believe that broken clock. — creativesoul -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

What do you mean by "propositional content"? What are you pointing at when you use the string of scribbles, "propositional content"?Maybe regardless of any specific card game, but the challenge here is to express the propositional content of that image (something that an image can share with sentences, different propositional attitudes, different languages): so is the propositional content of that image rendered by “this is a seven of diamonds” or “this is a seven of diamonds in standard 52-card deck” or “this is a card of diamonds different from a 1 to 6 or 8 to 13 of diamonds” or “this is a seven of a suit different from clubs, hearts, spades” or “this is a card with seven red diamond-shaped figures and red shaped number seven arranged so and so” or any combination of these propositions? All of them are different propositions which one is the right one? BTW “this” is an indexical, and shouldn’t be part of the content of an unambiguous proposition: so maybe the propositional content is “something is a seven of diamonds”? And so on.

At least this is how I understand the philosophical task of proving that images have propositional content, but I'm neither sure that others understand this philosophical task in the same way I just drafted, nor that this task can be accomplished successfully. — neomac

You seem to be confusing the card with the deck. I don't need to know it's relationship with other things to know that it is a sheet of paper with red ink in shape of diamonds and a "7". If you want me to know the relationship it has with other things, then I would need to see the image of those things as well. The propositions you propose cannot be discerned by merely looking at a 7 of diamonds. I would have to observe it in a box with the rest of the cards, or used with the other cards. -

neomac

1.6k

neomac

1.6k

> What do you mean by "propositional content"? What are you pointing at when you use the string of scribbles, "propositional content”?

I take it to mean, something that at least can be shared by different sentences (e.g. “Jim loves Alice” and “that guy called Jim loves Alice” ), by different propositional attitudes (e.g. I believe that Jim loves Alice, I hope that Jim loves Alice), by different languages (e.g. “Jim loves Alice” and “Jim aime Alice”) and determines their usage/fitness conditions. Those who theorize about propositions have richer answers than this of course (e.g. Frege’s propositions, Russell’s propositions, unstructured propositions, etc.). But I’m not a fan of these theories, so I’ll let others do the job.

Anyways, I hear people wondering about images as propositions or as having propositional content, without elaborating or clarifying, so this was my piece of brainstorming about this subject.

> You seem to be confusing the card with the deck. I don't need to know it's relationship with other things to know that it is a sheet of paper with red ink in shape of diamonds and a “7".

To know that I’m confusing the propositional content of that image, presupposes that you know what the propositional content of that image is. But I’m not convinced it’s that simple, see what you just wrote about that image: <it is a sheet of paper with red ink in shape of diamonds and a “7”> while you previously wrote something like: <it’s a seven of diamonds >. Is it essential for the propositional content of that image the mention of ink or paper? A seven of diamonds tattooed on the the body doesn’t share the same propositional content of the image on paper? How about the arrangement of the diamonds on the surface of the card? How about the shade of red? How about the change of light condition under which the image is seen? If I warped that image with an image editor to make it hardly recognisable but still recognisable after some time as a 7 of diamonds, shouldn’t we include in the propositional content of that image all the features that allowed me to recognise it as a 7 of diamonds, despite the warping? And so on…

Again, I’m just brainstorming, so no strong opinion on any of that. Indeed I was hoping to get some feedback from those who talk about propositional content of images, or images as propositions. -

Banno

30.6kWhat I do not understand is the move to set (that broken clock) outside of the scope of Jack's belief and replace it with (that clock) when the example hinges upon the fact that the clock is broken but Jack believes what it says. Jack does not know it is broken, so he cannot believe that it is broken. — creativesoul

Banno

30.6kWhat I do not understand is the move to set (that broken clock) outside of the scope of Jack's belief and replace it with (that clock) when the example hinges upon the fact that the clock is broken but Jack believes what it says. Jack does not know it is broken, so he cannot believe that it is broken. — creativesoul

SO you do not understand that "the broken clock" is not a description Jack could correctly make? That "The broken clock" could not be within the scope of Jack's belief? -

frank

18.9k

frank

18.9k

It's that "broken clock" is an extensional definition, while believes is an intensional operator.

The typical example of intension is

Jack believes Stephen King's first novel is The Shining.

If we stuck an extensional definition in there it would read

Jack believes that Carrie is The Shining.

Same thing.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum