-

Deleteduserrc

2.8kI think a good way to look at language games is by reference to child's games, to play. Some games have strict rules, others are more free and loose. And the games can occasionally bleed into one another. Rules are often laid down while the game is already happening, to give it a coherence that will allow it to continue- etc etc.

Deleteduserrc

2.8kI think a good way to look at language games is by reference to child's games, to play. Some games have strict rules, others are more free and loose. And the games can occasionally bleed into one another. Rules are often laid down while the game is already happening, to give it a coherence that will allow it to continue- etc etc. -

Luke

2.7k

Luke

2.7k

I apologise if I have contributed to any derailing, but I must say that it's unclear to me exactly what question you are asking, or what your enquiry is, in this discussion.

So in what light should we see Wittgenstein? — Mongrel

One of the main aims of Wittgenstein's later philosophy (or philosophical therapy) is to "bring words back from their metaphysical to their everyday use." (116) Language games are one of the devices that Wittgenstein uses to restore some perspective and ground language as an activity rather than as some idealised abstraction: the received view of many philosophers. As Wittgenstein puts it:

(7) [my emphasis]I shall also call the whole, consisting of language and the actions into which it is woven, the "language-game".

(23)Here the term "language-game" is meant to bring into prominence the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or of a form of life.

I think that your view of having "a transcendent viewpoint on language" is the kind of metaphysics that Wittgenstein is trying to dispel with his introduction of language games. But please clarify if this does not address your enquiry about language games. -

ernestm

1kIt's been a long time since I studied it, but I think Luke expresses this correctly. A language game does not need to attach 'meaning' to utterances, although it could, W.'s point was more that there is no necessity to consider there being any 'meaning' to an utterance beyond mutual understanding of the intended action to be caused by an utterance. That is, W. accepts the existence of causality attached to speech acts, but not meaning attached to words.

ernestm

1kIt's been a long time since I studied it, but I think Luke expresses this correctly. A language game does not need to attach 'meaning' to utterances, although it could, W.'s point was more that there is no necessity to consider there being any 'meaning' to an utterance beyond mutual understanding of the intended action to be caused by an utterance. That is, W. accepts the existence of causality attached to speech acts, but not meaning attached to words. -

Mongrel

3kI think that your view of having "a transcendent viewpoint on language" is the kind of metaphysics that Wittgenstein is trying to dispel with his introduction of language games. But please clarify if this does not address your enquiry about language games. — Luke

Mongrel

3kI think that your view of having "a transcendent viewpoint on language" is the kind of metaphysics that Wittgenstein is trying to dispel with his introduction of language games. But please clarify if this does not address your enquiry about language games. — Luke

This is true. What I failed to understand is that "language games" is not a theory of meaning. It's a lead up to a rejection of any such theory. -

Marchesk

4.6kEach has rules. As TGW says, professional rigour sometimes tries to partition off ordinary language meanings from meanings in professional practice. — mcdoodle

Marchesk

4.6kEach has rules. As TGW says, professional rigour sometimes tries to partition off ordinary language meanings from meanings in professional practice. — mcdoodle

Kind of like how the sun rises and sets in ordinary language, but astronomy would talk about the rotation of the Earth?

The point being that ordinary language can be misleading at times, and it can contain assumptions that are wrong. People did use to think the Earth was stationary, and the sun and moon revolved around it. -

ernestm

1kWell I am glad you understand the difference, but in Wittgenstein's case, it is fair to say his intent was not to claim meaning does not exist. Rather his intent was to demonstrate that language is a 'game' or 'tool' which can contain logical propositions, but there is no need for a theory of description. That bypasses the Russell-Whitehead paradox of non-existent references, and voids other theories of descriptive naming, replacing them with Kripke's idea of causal reference. But it does not imply that W. denied the existence of meaning. Instead he just had nothing to say on it one way or the other.

ernestm

1kWell I am glad you understand the difference, but in Wittgenstein's case, it is fair to say his intent was not to claim meaning does not exist. Rather his intent was to demonstrate that language is a 'game' or 'tool' which can contain logical propositions, but there is no need for a theory of description. That bypasses the Russell-Whitehead paradox of non-existent references, and voids other theories of descriptive naming, replacing them with Kripke's idea of causal reference. But it does not imply that W. denied the existence of meaning. Instead he just had nothing to say on it one way or the other.

One could perhaps say that W. believed it meaningless to discuss meaningfulness. But W. later did accept the existence of intent, and therefore causality based on intent. Austin did some very interesting work to extend W.'s model to explain utterances such as imperatives, which are beyond the conventional scope of formal logic.

Other theorists have denied the existence of intent, believing that there is in fact a correlation between material objects, states, and events and the words of language, but that it exists in a purely mechanical way. They hold ideas of conscious intent and free will are themselves confusions, and that is the reductionist method which has resulted in popular deflationary theories.

It is definitely true these are a form of logical positivism, but as it does not accept W.'s later thoughts on intent, such deflationary theories are really reductionist versions of Wittgenstein's early theory, which have gained popularity as the tremendous advances in scientific knowledge have so impressed modern thinkers that they believe strong materialism is the only reality. Therefore they wrongly consider themselves realists rather than linguists. Obviously that is wrong, as the basis of their argument denies our ability to know what reality actually is, beyond the language we use to accomplish goals. -

Mongrel

3kBut it does not imply that W. denied the existence of meaning. Instead he just had nothing to say on it one way or the other. — ernestm

Mongrel

3kBut it does not imply that W. denied the existence of meaning. Instead he just had nothing to say on it one way or the other. — ernestm

This is correct. He became deflationary about meaning theories. One may occasionally learn a definition ostensively, but there's so much language one would already have to understand to learn that way (foreshadowing Chomsky), that the point doesn't generalize. Likewise there may be cases of rule following, but people frequently speak without thinking at all (in line with what csalisbury said earlier), he actually finally ditches language games as well as a theory of meaning. He concluded that there's nothing to theorize about.

Not sure why he didn't go the route Chomsky did.. he was close to it. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kOne of the main aims of Wittgenstein's later philosophy (or philosophical therapy) is to "bring words back from their metaphysical to their everyday use." (116) Language games are one of the devices that Wittgenstein uses to restore some perspective and ground language as an activity rather than as some idealised abstraction: the received view of many philosophers. As Wittgenstein puts it: — Luke

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kOne of the main aims of Wittgenstein's later philosophy (or philosophical therapy) is to "bring words back from their metaphysical to their everyday use." (116) Language games are one of the devices that Wittgenstein uses to restore some perspective and ground language as an activity rather than as some idealised abstraction: the received view of many philosophers. As Wittgenstein puts it: — Luke

If you take language away from the metaphysician, how is the metaphysician going to do metaphysics? I assume by the claim that this is "therapy", that metaphysics is apprehended as a form of illness. Does anyone really believe that forcing the sick person to shut up is an acceptable form of therapy? -

ernestm

1kNow I again have to point out that you are both overextending the cynicism of positivism. The significance of positivism is that it is possible for communication to take place without a theory of descriptions. In a positive way, not a negative way.

ernestm

1kNow I again have to point out that you are both overextending the cynicism of positivism. The significance of positivism is that it is possible for communication to take place without a theory of descriptions. In a positive way, not a negative way.

So W demonstrates that a more sophisticated theory is not necessary. However that does not imply that more sophisticated ideas of meaning do not exist. It's only so much as to say that more sophisticated theories are not necessary. Calling that 'deflationary' and saying that metaphysics does not exist is far beyond postivism's objective. -

Mongrel

3kA presentation of a theory of truth will draw questions about whether it meets its own criteria. Same thing for a theory of meaning. Does the language it's presented in gain meaning according to the content of the theory?

Mongrel

3kA presentation of a theory of truth will draw questions about whether it meets its own criteria. Same thing for a theory of meaning. Does the language it's presented in gain meaning according to the content of the theory?

With Witty we don't have to worry over that. He offers no theory of meaning. If you have a favored theory of meaning, that's fine. There's nothing blocking you. -

ernestm

1kStrangely, I just had a long conversation last night with another person explaining W's point, starting at the end of page 2 here. https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/1314/wittgenstein/p2

ernestm

1kStrangely, I just had a long conversation last night with another person explaining W's point, starting at the end of page 2 here. https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/1314/wittgenstein/p2

And I only got 5 hours sleep. So if you'll excuse me, that took several hours to write to Marchesk, so if you have a problem with it being baloney, please comment on that there. -

ernestm

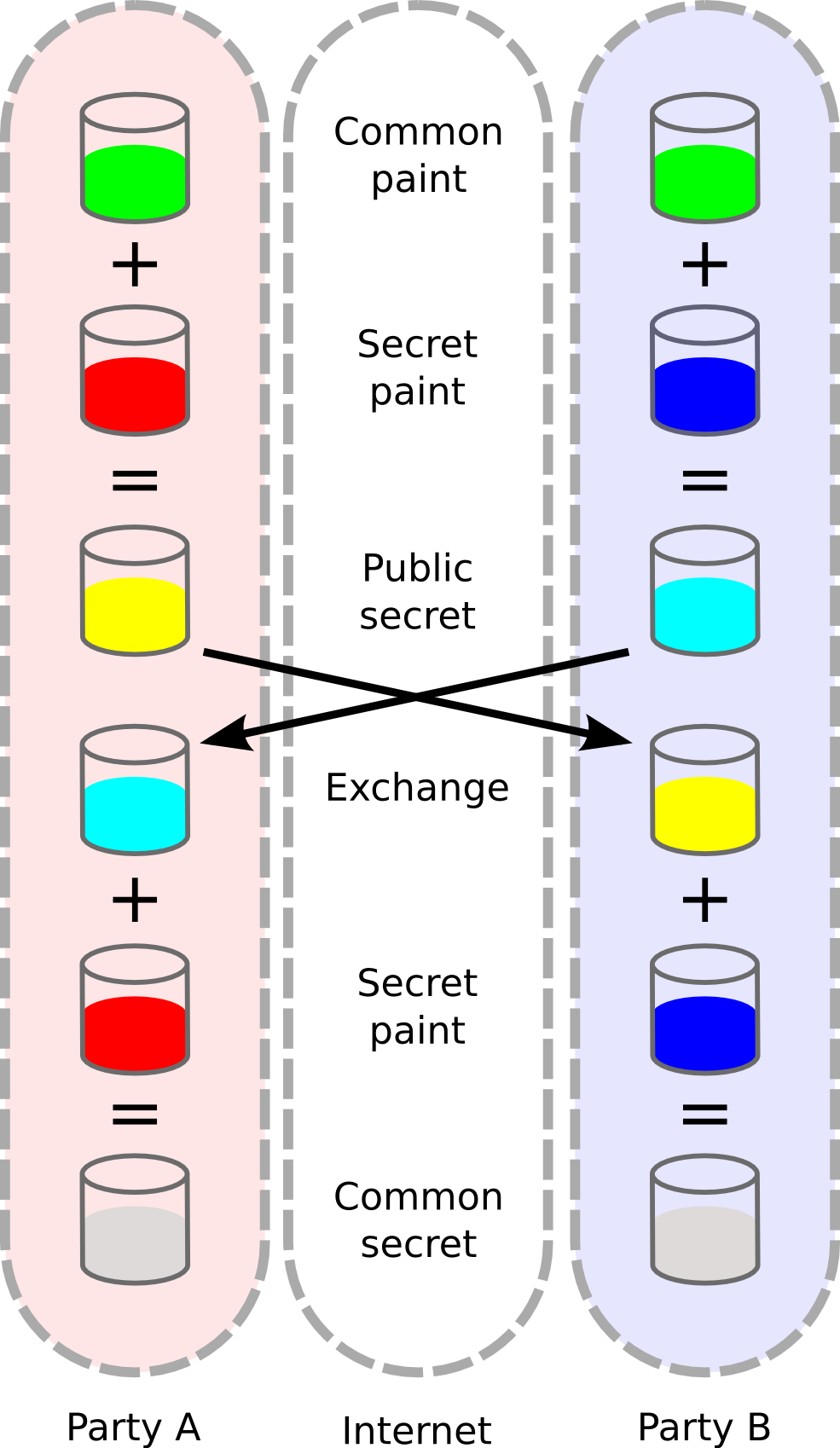

1kI guess the only thing I have to add to that is, while I wake up, is that I also had a problem with W's mysticism, until I learned about how HTTPS authentication works, bizarrely. This is the use of a thing called a 'certificate' to establish a 'shared secret.' The thing about it is, neither party in the authentication exchange actually knows what the other party knows, but both sides can authenticate the other party from their own private data. After I understood that, W. made perfect sense to me.

ernestm

1kI guess the only thing I have to add to that is, while I wake up, is that I also had a problem with W's mysticism, until I learned about how HTTPS authentication works, bizarrely. This is the use of a thing called a 'certificate' to establish a 'shared secret.' The thing about it is, neither party in the authentication exchange actually knows what the other party knows, but both sides can authenticate the other party from their own private data. After I understood that, W. made perfect sense to me.

The original shared secret theory is called Diffie and Helman 'key exchange," described here. One doesn't easily find more abstract explanations on the web due to security concerns.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffie%E2%80%93Hellman_key_exchange

There you will see this basic diagram showing how shared secrets work. A and B (Alice and Bob) can communicate with each other successfully after encrypting their communications with a private color, but neither party knows what the other's private color is. -

ernestm

1kSure, here I'll explain the algorithm in simpler terms, by using a shared color code of modulo 10 base 2:

ernestm

1kSure, here I'll explain the algorithm in simpler terms, by using a shared color code of modulo 10 base 2:

Alice has private color code 100

Bob has private color code 200

Alice says 17 modulo 10 base 2, that is 1

Bob says 33 modulo 10 base 2, that is 1

Alice hears 1 base 2 modulo 100, that is 1

Bob hears 1 base 2 modulo 200, that is 1

Now Alice and Bob have a shared secret 1. Neither of them know the private color code of the other. That's the basis of the theory, but picking shared color code that works for all numbers is not quite as simple as that (they both have to be primes and the modulo has to be in the base range), but it gives the idea. -

ernestm

1kSo here is how it works in w's theory:

ernestm

1kSo here is how it works in w's theory:

Alice [secret] is hungry ->

Alice says 'Bob please bring in groceries from car.'

Bob hears 'Alice wants me to get dressed to outside.'

Bob says 'It is raining'

Alice hears 'Bob is not hungry.'

Alice says 'it is not raining.'

Bob hears 'Alice insists I get dressed to go outside.'

Bob says 'if you think it's not raining, you bring in the groceries, and I'll cook dinner.'

Wittgenstein's point is, it is totally irrelevant to the conclusion whether the proposition 'it is raining' is true or not, Bob doesn't know Alice is hungry, and Alice doesn't know Bob doesn't want to get dressed, and yet even so, the conclusion is logically coherent, and there has been effective communication. -

ernestm

1kW had an idea of intent and causality, but he did not agree that a theory of descriptions is necessary. He rather avoids topics like 'meaning' and 'metaphysics' because they are not useful to his point, so he doesn't have anything to say about them. That leaves it up to other people to decide whether meaning exists and what metaphysical grounds there are for it, and that's why there are different derivations from his theory, but all W had to say was that there can be effective communication without a theory of descriptions, that is, he REALLY did not agree with Russell/Whitehead. Kripke is compatible with both approaches so he's often cited as a resolution.

ernestm

1kW had an idea of intent and causality, but he did not agree that a theory of descriptions is necessary. He rather avoids topics like 'meaning' and 'metaphysics' because they are not useful to his point, so he doesn't have anything to say about them. That leaves it up to other people to decide whether meaning exists and what metaphysical grounds there are for it, and that's why there are different derivations from his theory, but all W had to say was that there can be effective communication without a theory of descriptions, that is, he REALLY did not agree with Russell/Whitehead. Kripke is compatible with both approaches so he's often cited as a resolution. -

Janus

17.9kSorry.. not quite following you. What strict philosophical use? — Mongrel

Janus

17.9kSorry.. not quite following you. What strict philosophical use? — Mongrel

For example, the exclusively philosophical use of the term 'substance'. Or Heidegger's use of 'dasein'. You must be aware that philosophers have developed their own lexicons, that are not entirely unrelated to, although obviously different from, "ordinary" usage? Isn't this what Wittgenstein means by language going on holiday? I mentioned "irony" here because philosophical usages of terms are usually "strict" or restricted. Aristotle means something quite different, in some ways but not in others,by 'substance' than Spinoza does, for example; and they both mean something different than ordinary usage of the term does.

So, if W means to say that the philosophical usage of the term 'substance' creates the philosophical problem of substance, I am wondering whether, instead, the various (but related both to each other and ordinary usage) philosophical definitions of 'substance' evolve out of the need to find ways to formulate and imagine clearly already (perhaps not so clearly) imagined philosophical problems. -

ernestm

1kWhat I did, with a little time, was roll up the prior discussion into a separate thread:

ernestm

1kWhat I did, with a little time, was roll up the prior discussion into a separate thread:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/1349/wittgensteins-mysticism-or-not-#Item_1

It's not quite the standard view, but as I am describing the mysticism part I felt I could take a little license on it. Thanks for the conversation. -

Marchesk

4.6ksn't this what Wittgenstein means by language going on holiday? — John

Marchesk

4.6ksn't this what Wittgenstein means by language going on holiday? — John

But it's not a fair criticism, because every field of specialty will adopt terms that have a specific meaning in the field. The reason philosophers do it is because ordinary language has enough confusions and ambiguity. So if we're debating free will, it's very helpful to know if someone is arguing from a libertarian position rather than a compatibilist, for example. That helps clarify (somewhat) the issue. "Free will" itself is way too broad, full of ambiguity and unspoken assumptions. To even approach the problem, you need to figure out what being free and having a will might possibly mean, and why people care about it. -

Banno

30.6kErnestm has a clear approach, worth reading. However I was struck by this:That is, W. accepts the existence of causality attached to speech acts, but not meaning attached to words. — ernestm

Banno

30.6kErnestm has a clear approach, worth reading. However I was struck by this:That is, W. accepts the existence of causality attached to speech acts, but not meaning attached to words. — ernestm

One of the obvious and interesting characteristics of language is that from a limited vocabulary an unlimited number of sentence may be constructed. This is possible because words are used for similar purposes in different sentences.

So yes, causality is attached to speech acts, but also there are patterns or rules for the use of words. -

Marchesk

4.6kWhat you say is entirely in accordance with what I was getting at, though; which is that philosophers formulate new definitions and qualifications of terms in order to clarify problems that, in a sense, already exist (in the sense of being implicit). — John

Marchesk

4.6kWhat you say is entirely in accordance with what I was getting at, though; which is that philosophers formulate new definitions and qualifications of terms in order to clarify problems that, in a sense, already exist (in the sense of being implicit). — John

Right, I don't see it as an abuse of language that creates philosophical problems that otherwise wouldn't exist, although that could be the case in some instances. Rather, philosophers are trying to make explicit the philosophical problems already implicit. -

Mongrel

3kSo, if W means to say that the philosophical usage of the term 'substance' creates the philosophical problem of substance, I am wondering whether, instead, the various (but related both to each other and ordinary usage) philosophical definitions of 'substance' evolve out of the need to find ways to formulate and imagine clearly already (perhaps not so clearly) imagined philosophical problems. — John

Mongrel

3kSo, if W means to say that the philosophical usage of the term 'substance' creates the philosophical problem of substance, I am wondering whether, instead, the various (but related both to each other and ordinary usage) philosophical definitions of 'substance' evolve out of the need to find ways to formulate and imagine clearly already (perhaps not so clearly) imagined philosophical problems. — John

Per Soames, W was saying that philosophy in general is a waste of time because he assumed that any philosophical truth must be analytic, apriori, and necessary. The world doesn't need philosophers to establish anything. Linguistic competency is an instinctive application of words amidst social conditioning. There's no valid questioning to be done. Philosophers should shut up and get a real job.

Soames, unlike W, is very rigorous. When he reveals the holes and inconsistencies in W's outlook, it's one careful step at a time... which is cool.

I was just recently thinking about jargon, though. I got interested in the history of Scientology, whose members are jargonites. Jargon sets one off from the crowd, so it serves to reinforce a sort of inbred community. It creates unity, possibly drawing people to bypass thought. 'We don't care if you think about what you're saying.. just say the special words in the right order...'

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum