-

schopenhauer1

11kYou have to read the whole thing to get it. This book is a demonstration of philosophical nonsense. For a purpose. — Tate

schopenhauer1

11kYou have to read the whole thing to get it. This book is a demonstration of philosophical nonsense. For a purpose. — Tate

I think it was his genuine theory and he didn’t want to contradict himself so had to claim it as nonsense. I don’t think he wrote it to show what nonsense looks like. There is a difference. -

Fooloso4

6.2k

Fooloso4

6.2k

Wittgenstein uses the terms 'Sinn' in two different ways. What is "meaningful", as used in the SEP article, is what has a referent in the world. But what cannot be said is meaningful in the sense of being important or significant for us.

In a now famous letter to von Ficker he says:

The book's point is an ethical one. I once meant to include in the preface a sentence which is not in fact there now but which I will write out for you here, because it will perhaps be a key to the work for you. What I meant to write, then, was this: My work consists of two parts: the one presented here plus all that I have not written. And it is precisely this second part that is the important one. My book draws limits to the sphere of the ethical from the inside as it were, and I am convinced that this is the ONLY rigorous way of drawing those limits. In short, I believe that where many others today are just gassing. I have managed in my book to put everything firmly in place by being silent about it. And for that reason, unless I am very much mistaken, the book will say a great deal that you yourself want to say. Only perhaps you won't see that it is said in the book. For now, I would recommend you to read the preface and the conclusion, because they contain the most direct expression of the point of the book.

Because one must first climb the ladder before throwing it away, the propositions should not simply be dismissed by someone who has not climbed the rungs. After all, he would not have written it if it is just to be disregarded by a novice reader.

Reading Schopenhauer would prime you to get it, though. It's similar stuff. — Tate

In a remark to Drury:

Whereas my interest is in showing that things which look the same are really different. I was thinking of using as a motto for my book a quotation from King Lear: ‘I’ll show you differences.’ -

Fooloso4

6.2k

Fooloso4

6.2k

I am reminded of something William Buckley once said:

If you think Harry Jaffa is hard to argue with, try agreeing with him. -

Tate

1.4k. I don’t think he wrote it to show what nonsense looks like. — schopenhauer1

Tate

1.4k. I don’t think he wrote it to show what nonsense looks like. — schopenhauer1

That is the point, though.

When he says the logic of the world is sympathetic to the logic of language, your response should be: how does he know that? -

schopenhauer1

11k

schopenhauer1

11k

So it’s one long troll?

I don’t think he was that deliberate about it. I think it’s more like “it’s all nonsense but this is the most accurate of nonsense” (in other words not really nonsense like the others are nonsense). -

Fooloso4

6.2kI climbed it. I got it. It's not really that complicated. — Tate

Fooloso4

6.2kI climbed it. I got it. It's not really that complicated. — Tate

Scholars have been debating the meaning of the text ever since it was published, but you read an article in the SEP and went from:

I'm going off the SEP article right now. I'm reading the text as well. — Tate

to declaring you have climbed the latter in a few hours.

To quote you:

This sounds incredibly arrogant. — Tate

You don't even know enough to know that you do not know. From the SEP article you are relying on:

The Tractatus is notorious for its interpretative difficulties. In the decades that have passed since its publication it has gone through several waves of general interpretations.

The interpretive difficulties remain. But you have it all figured out. -

Banno

30.6kThe Tractatus is wrong if it fails to prove the very foundation it stands on. — schopenhauer1

Banno

30.6kThe Tractatus is wrong if it fails to prove the very foundation it stands on. — schopenhauer1

Have you noticed the thread on the elephant in the room?

Jackson wrongly attributed the phrase to Aristotle, and seems to have misunderstood the use of the aphorism. But this quote on the notion of truth is apt to our discussion here. Or we might consider Ryle's example of a new student shown the faulty buildings, library, Chancellery and so on, asking "but where is the University?"...nothing can be proven to an extreme skeptic who will not acknowledge what is before you. — Jackson

I suppose there is an attitude to philosophy, from at least Descartes, that insists on a derivation from some foundation, from first principles. I've tried to show you that this is problematic, using the examples of finding a meaning in the dictionary and following a rule. Each of these leads to a regress or circularity. This is the case with any search for an ultimate foundation - the foundation must itself rest on something. Since we do understand meaning and do follow rules, there must be a way to avoid the circularity or regress.

The Tractatus begins to show how this can be done.

4.1212 What can be shown, cannot be said.

Or consider:

4.126 ...(A name shows that it signifies an object, a sign for a number that it signifies a number, etc.)

Looking in the Tractatus for a proof of "the very foundation it stands on" is like looking for the university among the buildings, or demanding proof of the elephant that is immediately before you.

Sometimes folk don't even see the ladder. -

Tate

1.4kSo it’s one long troll? — schopenhauer1

Tate

1.4kSo it’s one long troll? — schopenhauer1

Not exactly. He's making fun of Schopenhauer in some respects: the stuff about the subject being the limit of the world.

You should be laughing at the end. It's awesome. -

Banno

30.6kIt is not as Wittgenstein said that propositions show the logical form of reality, rather propositions represent private subjective experiences, and it is these private subjective experiences that show the logical form of reality. — RussellA

Banno

30.6kIt is not as Wittgenstein said that propositions show the logical form of reality, rather propositions represent private subjective experiences, and it is these private subjective experiences that show the logical form of reality. — RussellA

Of course for Wittgenstein, if we construe the grammar of sensation as object and designation, then the object - the "private subjective experience"-drops out or consideration. -

Banno

30.6kFH Bradley

Banno

30.6kFH Bradley

Famously, Bradley brought a vicious regress argument against external relations. In his original version of 1893, Bradley presented a dilemma to show that external relations are unintelligible: either a relation R is nothing to the things a and b it relates, in which case it cannot relate them. Or, it is something to them, in which case R must be related to them. — RussellA

I've not been able to get a clear idea of this argument. Can you set it out?

It seems to me to draw on an odd notion of relations.

Perhaps a new thread? -

RussellA

2.6kOf course for Wittgenstein, if we construe the grammar of sensation as object and designation, then the object - the "private subjective experience"-drops out or consideration. — Banno

RussellA

2.6kOf course for Wittgenstein, if we construe the grammar of sensation as object and designation, then the object - the "private subjective experience"-drops out or consideration. — Banno

The "beetle" plays an important role in the language game

Wittgenstein in Tractatus proposed that thought is language

4 "The thought is the significant proposition".

If it is true as Wittgenstein proposes that thought is language, the thought of the private subjective experience the postbox is red is also the proposition "the postbox is red". In which case, the statement (propositions represent private subjective experiences, and it is these private subjective experiences that show the logical form of reality) is equivalent to the statement (propositions show the logical form of reality).

The question is, is Wittgenstein correct in proposing that thought is language.

Thought existed before language

There are two main theories as to how language evolved, either i) as an evolutionary adaptation or ii) a by-product of evolution and not a specific adaptation. As feathers were an evolutionary adaptation helping to keep the birds warm, once evolved, they could be used for flight. Thereby, a by-product of evolution rather than a specific adaptation.

Similarly for language, the development of language is relatively recent, between 30,000 and 1000,000 years ago. As the first animals emerged about 750 million years ago, this suggests that language is a by-product of evolution rather than an evolutionary adaptation.

It therefore seems sensible to propose that language is a by-product of evolution and uses pre-existing thoughts.

The relationship between propositions and thoughts

The proposition "the postbox is red" is linked to my thought that the postbox is red. But my private subjective thought of the colour red cannot be described in words to someone else, in that I cannot describe the private subjective experience of the colour red to someone born blind. My private subjective thought that it is unethical to kill spiders can be justified but not described to someone else.

All propositions are linked to thoughts, but not all thoughts are linked to propositions.

Representationalism and Isomorphism

In a computer, a picture of a house may be labelled "house", but it does not follow that the word "house" is isomorphic with the picture of the house. The word "house" represents the picture house. Similarly, in the mind, the word "red" is not isomorphic with our thought of red. The word "red" represents the thought red.

The word "red" represents the thought red, and the thought red is isomorphic with red in the world.

Description and acquaintance

The proposition "Rembrandt is a painter" is a description of Rembrandt as a painter. By seeing a picture of a Rembrandt painting, which is isomorphic with the person Rembrandt, we gain an acquaintance with Rembrandt. Similarly, the proposition "the postbox is red" only describes a state of affairs, and without giving us a picture of the state of affairs, it doesn't allow us to become acquainted with the red postbox.

Words describe whilst pictures give us acquaintance.

Conclusion

If Wittgenstein was correct that thought is language, the statement "language represents thoughts and thoughts are isomorphic with reality" can be reduced to "language is isomorphic with reality".

However. I have argued that whilst language may represent some thoughts, all thoughts are isomorphic with reality. In such a case, the expanded statement "language represents some thoughts and all thoughts are isomorphic with reality" cannot be reduced to "language is isomorphic with reality".

IE, Wittgenstein is incorrect in para 4.01 that "The proposition is a picture of reality", rather, "the proposition represents some thoughts, where all thoughts are isomorphic with reality".

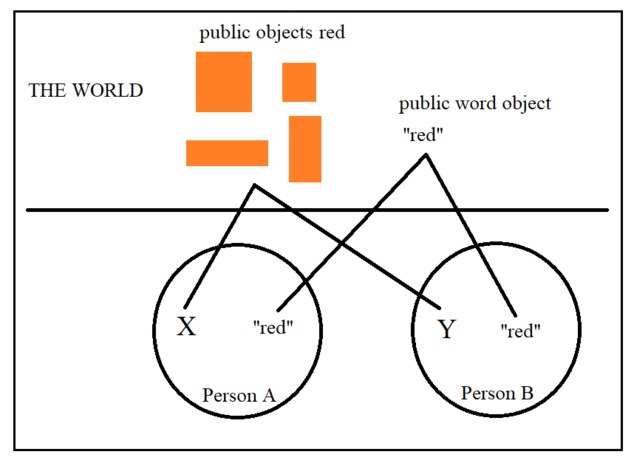

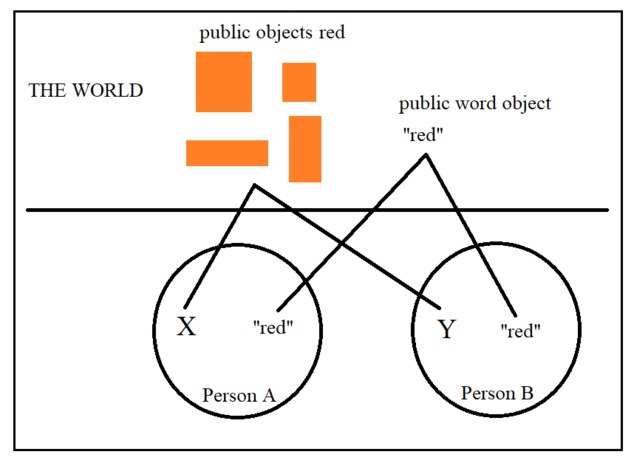

A diagram may show the correspondence between language and thought.

Public language and private thoughts

Person A when observing the world has the private subjective experience X. They link their private subjective experience X with the public word object "red". Person B when observing the world has the private subjective experience Y. They link their private subjective experience Y with the public word object "red"

Persons A and B can sensibly discuss the public object red, even though Person A's subjective experience X may be different to Person B's subjective experience Y.

Wittgenstein's "world"

1. The world is everything that is the case

3.03 We cannot think anything unlogical, for otherwise we should have to think unlogically.

The Tractatus may be read that Wittgenstein's "world" exists in the mind of whoever is doing the thinking.

Wittgenstein's "beetle"

Para 293 Philosophical Investigations - Here it would be quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box................... The thing in the box has no place in the language-game at all.........for the box might even be empty.

The private subjective experience X is a fact, is knowledge, for person A, and the private subjective experience Y is a fact, is knowledge, for person B.

Without these facts, this knowledge of X and Y, Persons A and B would not be able to engage in any language game using the public word object "red".

"The postbox is red" is true iff the postbox is red

As X may or may not be the same as Y, it follows that for each observer there will be one truth, although each observer may have a different truth. -

Fooloso4

6.2kWittgenstein in Tractatus proposed that thought is language

Fooloso4

6.2kWittgenstein in Tractatus proposed that thought is language

4 "The thought is the significant proposition". — RussellA

From the preface:

Thus the aim of the book is to draw a limit to thought, or rather—not to thought, but to the expression of thoughts ... It will therefore only be in language that the limit can be drawn ...

A thought is expressed in language. This does not mean that a thought is language. The expression, language, is not what is expressed, the thought.

3.1 In a proposition a thought finds an expression that can be perceived by the senses. -

RussellA

2.6kThought is linguistic for Wittgenstein. — Tate

RussellA

2.6kThought is linguistic for Wittgenstein. — Tate

I think so.

This is not Kant. There is no a priori knowledge. It's all just a world put together with the same logic that is the backbone of language. — Tate

Critique of Pure Reason - A239 - "We can only cognize objects that we can, in principle, intuit. Consequently, we can only cognize objects in space and time, appearances. We cannot cognize things in themselves."

No system can function without some degree of an innate, a priori, pre-existing structure. I can see the colour red because I have the innate ability to see red. I cannot see the colour ultraviolet because I don't have the innate ability to see ultraviolet. A kettle functions as a kettle because it has a particular structure. A kettle cannot function as a toaster.

Without an innate, a priori, pre-existing ability to know something, we could never make sense of the world. -

Fooloso4

6.2k@RussellA

Fooloso4

6.2k@RussellA

What do you make of this? Where does language enter the picture?

3.1431 The essence of a propositional sign is very clearly seen if we imagine one composed of spatial objects (such as tables, chairs, and books) instead of written signs.

Then the spatial arrangement of these things will express the sense of the proposition. -

schopenhauer1

11kNot exactly. He's making fun of Schopenhauer in some respects: the stuff about the subject being the limit of the world.

schopenhauer1

11kNot exactly. He's making fun of Schopenhauer in some respects: the stuff about the subject being the limit of the world.

You should be laughing at the end. It's awesome. — Tate

Right, but then why take it seriously? If he intended for you to take it seriously then his nonsense is supposed to be genuine nonsense. Since its ALL nonsense, why not go full hog and justify his ontology with a metaphysics akin to Kant or Schopenhauer? Why start by ASSUMING objects?

In other words, you (he) cannot squirm out of liability of defending his claim simply by calling it nonsense if you (he) wants to discuss it as if it has some truth-value. Otherwise, why discuss it? Are you saying, it's like discussing a fiction or poetry? If so, why aren't you analyzing other fiction poetry? Clearly you think there is something philosophically appealing about this that separates it out from other "fictions".

And I think I do understand the connection with Schopenhauer's understanding of the world as representation and if he was doing so, he should explicitly try to do so.. Schopenhauer himself did so with his ideas of the Fourfold Root of the Principles of Sufficient Reason.. basically laying out in detailed terms how it is that the world of phenomenon is rooted in this fourfold root and thus limited to that. I think that Witt should have been more explicit if he was doing that connection though, but instead he starts off with "objects" a kind of middling ontology with no basis other than if one looks up the vague connection with Russel's idea of objects.. which then presupposes more than is necessary on the reader in a philosophical work. Certainly, I don't think he thought of his own writings as a prank. He wanted it to be taken seriously and as philosophy, not as a shaggy dog writing piece that leads you nowhere. -

Tate

1.4kCritique of Pure Reason - A239 - "We can only cognize objects that we can, in principle, intuit. Consequently, we can only cognize objects in space and time, appearances. We cannot cognize things in themselves." — RussellA

Tate

1.4kCritique of Pure Reason - A239 - "We can only cognize objects that we can, in principle, intuit. Consequently, we can only cognize objects in space and time, appearances. We cannot cognize things in themselves." — RussellA

I guess the metaphysics he presents would be compatible with Kant. It would be compatible with some kind of mystical view.

Does it matter though? In the context of the whole book? -

Tate

1.4kClearly you think there is something philosophically appealing about this that separates it out from other "fictions". — schopenhauer1

Tate

1.4kClearly you think there is something philosophically appealing about this that separates it out from other "fictions". — schopenhauer1

Yes. I'm not sure why Wittgenstein bugs you. If you're a Schopenhauer/Tolstoy/Kierkegaard fan, it seems to me you'd at least be curious about what's going on with the Tractacus. -

schopenhauer1

11kYes. I'm not sure why Wittgenstein bugs you. If you're a Schopenhauer/Tolstoy/Kierkegaard fan, it seems to me you'd at least be curious about what's going on with the Tractacus. — Tate

schopenhauer1

11kYes. I'm not sure why Wittgenstein bugs you. If you're a Schopenhauer/Tolstoy/Kierkegaard fan, it seems to me you'd at least be curious about what's going on with the Tractacus. — Tate

Haha, so eluding my whole point. If what he is writing is nonsense, then why not write nonsense on metaphysics.. It's all nonsense. If because it ties to "objects" is nonsense.. Then let's explain the metaphysics further. Why no reference to what he is trying to refer to here? -

Tate

1.4k

Tate

1.4k

You can read it. If you don't like it, fine. If you think his message is mystical, fine. If you think he was a materialist, fine.

I'm going to turn my back on you and read poetry. -

bongo fury

1.8kOne respect in which I think it fair to say that the Tractatus anticipates the PI is in arguing in terms of "thought" in such a way as to facilitate behaviourism, as opposed to the kind of psychology indulged here -

bongo fury

1.8kOne respect in which I think it fair to say that the Tractatus anticipates the PI is in arguing in terms of "thought" in such a way as to facilitate behaviourism, as opposed to the kind of psychology indulged here -

W's use of "thought" reminds me of how teachers in the UK tell 3rd-graders to recognise a complete sentence: as one that expresses "a complete thought". I.e. what it reminds me of is how to use but immediately get past the psychology, and to work with language and logic instead.

Like the teacher, he probably didn't mean "thoughts" to refer to identifiable brain events that correspond or fail to correspond to propositions. It was more a matter of putting the reference of symbols in the perfectly realistic context of our deliberate efforts to make sense of them.

The proposition "Rembrandt is a painter" is a description of Rembrandt as a painter. By seeing a picture of a Rembrandt painting, which is isomorphic with the person Rembrandt, we gain an acquaintance with Rembrandt. — RussellA

Does W say "acquaintance"? Or is this you critiquing him?

And do you not think that W claims that the proposition "Rembrandt is a painter" is isomorphic to the fact of Rembrandt being a painter? -

Banno

30.6kIf it is true as Wittgenstein proposes that thought is language, the thought of the private subjective experience the postbox is red is also the proposition "the postbox is red". — RussellA

Banno

30.6kIf it is true as Wittgenstein proposes that thought is language, the thought of the private subjective experience the postbox is red is also the proposition "the postbox is red". — RussellA

This notion of a "private, subjective experience" permeates your writing.

It is not used in the Tractatus.

For the purposes of exegesis,

Doesn't look right, since we have, as you note,The proposition "the postbox is red" is linked to my thought that the postbox is red. — RussellA

My bolding. It's not a link, but an equivalence.4 A thought is a proposition with a sense.

So you are not here setting out the tractatus in its own terms, but imposing that view on the text. You are not showing an internal inconsistency, but saying it is incompatible with another, external view.

For my part I don't think the notion of a private, subjective proposition is coherent, because a proposition is a piece of language and language is inherently public.

But that's another argument. Language is not moving information from one head to another.

In summary, you have not argued for an internal inconsistency in the Tractatus. You have argued that the Tractatus is inconsistent with another picture of language and mind, one with which I would take issue.

So does your argument hold? has already provided one critique: any thought can be put into propositional form. We can extend this to a definition such that if it cannot be expressed as a proposition it does not count as a thought. It might be a sensation, a feeling, an intuition, but not yet a thought.

You say

But that is not correct. Red and the thought of red are different things. If red is the thought of red then when you and I talk about the red sunset you would be talking about your thought-of-red and I about my thought-of-red, and so quite literally we would not be talking about different things. But I put it to you that we would be talking about the very same sunset and hence that the word "red" has a public and not a private use.The word "red" represents the thought red — RussellA

Indeed the notion of "the thought of red" is unclear. The red of the sunset the post box and the sports car are not the same. Which of these is "the thought of red"? Isn't it rather that we simply use the same word for a variety of different things? We do this in other case, why should it not just be that we use the word in this way? Why, indeed, must there be a something to which "red" refers? Not all words are nouns.

You say

But it is not clear here what "isomorphic" is doing here. It can't mean that all thoughts are true; "the post box is blue" is not isomorphic in that way with red post boxes. Yet the components, "is blue' and "the postbox", while they might be part of a thought, do not form a thought, a proposition, until brought together.I have argued that whilst language may represent some thoughts, all thoughts are isomorphic with reality. — RussellA

Would you care to address Bradley's regress? As i said, I do not understand the argument. Since you rely on it, perhaps you might explain it. -

schopenhauer1

11khy should it not just be that we use the word in this way? Why, indeed, must there be a something to which "red" refers? Not all words are nouns. — Banno

schopenhauer1

11khy should it not just be that we use the word in this way? Why, indeed, must there be a something to which "red" refers? Not all words are nouns. — Banno

I do get that you are mixing PI and Tractatus in your analysis, but is it appropriate to use later Witt here to give exegesis on Tractatus when he did not have that in mind yet when writing Tract? I am not saying you are wrong (that he did not mean that red was a thought), but he didn't mean yet that it was about the use of the word. That part is being smuggled in from later Witt. -

Banno

30.6kbut is it appropriate to use later Witt here to give exegesis on Tractatus — schopenhauer1

Banno

30.6kbut is it appropriate to use later Witt here to give exegesis on Tractatus — schopenhauer1

I'm at pains to seperate the bits; Witti said that the PI ought be read in conjunction with the Tractatus; problems with the tractatus are addressed in the PI by the author of the tractatus; so, yes. -

schopenhauer1

11k

schopenhauer1

11k

I guess I'm trying to understand this game. Are we trying to understand early Witt's ideas (good, bad, or ugly) QUA early Witt, or understand his ideas as they were critiqued by later Witt? I'm not sure, but I think Tate, Foolso4, and Bongo Fury are working on the game of early Witt qua early Witt. -

Banno

30.6kWhy start by ASSUMING objects? — schopenhauer1

Banno

30.6kWhy start by ASSUMING objects? — schopenhauer1

He doesn't. Objects are demanded by the nature of language.

2.021 Objects make up the substance of the world. That is why they cannot be composite.

2.0211 If they world had no substance, then whether a proposition had sense would depend on whether another proposition was true.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum