-

Olivier5

6.2ksomething fascinating — Tate

Olivier5

6.2ksomething fascinating — Tate

I guess this is important. The fascination of doubt, the sinking feeling one gets when contemplating one's cosmic ignorance. Socrates realized soon enough that we don't know much for sure. Oddly enough, one can get hooked on the contemplation of one's one insignificance, ignorance or confusion.

And yet, we still *know* some stuff for (almost) certain. We can approach certainty, apparently, or at least we all function daily -- and argue -- as if we could approach certainty.

Science certainly does so. It is predicated on the idea that careful human observation of phenomena and the careful application of human reason to such observations (classifying, comparing, theorizing) can help make sense of the world. If you don't believe in that, you're not a scientist. -

Tate

1.4k

Tate

1.4k

:up:Science certainly does so. It is predicated on the idea that careful human observation of phenomena and the careful application of human reason to such observations (classifying, comparing, theorizing) can help make sense of the world. If you don't believe in that, you're not a scientist. — Olivier5

Something like this? — Olivier5

Yep. :grin: -

Alkis Piskas

2.1k

Alkis Piskas

2.1k

First of all: Kudos for bringing in definitions! :up:

I always applaud this because it is quite rare --even a lot are against it!-- and I find it very important, esp. in discussions taking place in media like this one.

Now, I'm not sure if you want to refer strictly to this term and not to "Phenomenology", which is much more commonly used in philosophy. (This is the problem with "-isms": they are used as frameworks in which a subject is confined and quite often in a wrong way. person's position on a subject is bound.)

There are a lot more senses, which are recognized today as such, beyond the classic 5 ones: balance, weight, motion/movement/kinaesthesia, velocity/speed, spatial/orientation, body position, pressure, vibration, temperature, pain, and more ...We have five physical senses: sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell. — Art48

Certainly. But it looks to me that this is a subject of Phenomenology and not Phenomenalism. The word "how" betrays it. But then, maybe I am wrong. That's why I avoid to use "-isms" if their mentioning is not necessary. And I believe that using "Phenomenalism" in order to ask this interesting question and describe the subject related to it, is not at all necessary.So, how can we experience a tree? The answer seems to be we don’t directly experience a tree. — Art48

Now, having an "experience" of something can mean different things, but here I believe we mean having an immediate contact of an object via our senses. Right? This then becomes a knowledge about that object. This, although it is usually the right sequence, it can also work the other way around. Here's an example:

In a botanical garden that I'm vesting for the first time, I see a quite weird object that looks like tree but I am not sure; it could also be a plant. I come nearer and read the tag. It says: "Bottle tree". There. I have an experience of such a tree. And the next time I see it I will recognize it, i.e. I will know what it is, because my first experience became knowledge.

Next day, I talk about my very interesting visit to the botanical garden --there were a lot more of interesting things there-- to a friend and show him some photos I took, including that of the "bottle tree". My friend was intrigued and he visited too the garden after a few days. When he reached at the location of the "bottle tree" he immediately recognized from a distance, because he had a knowledge of it from the info I had given to him. He then also got an experience of it.

Well, a tree is not an abstract idea so that we have an idea of it. It is an object, something concrete. So I would say that, independently of its name, i.e. the word "three", it exists in our mind as an image connected to various data (knowledge) we have about it.our mind accesses the idea of “tree” because the idea makes sense of our sense data. — Art48

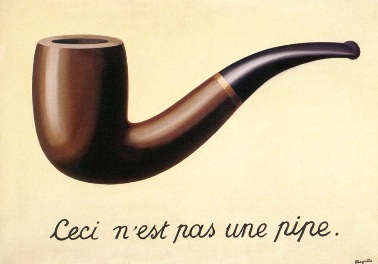

Here's how the Belgian surrealist painter René Magritte explains this phenomenon with his painting and a famous phrase:

"This is not a pipe". Indeed, it isn't; it's "an image of a pipe". -

Art48

500

Art48

500

I think it also qualifies as representative realism because I'm leaving the existence of external, independently-existing object an open question.That's phenomenalism as I understand it. — Tate

Because for millennia human beings have worked to understand what they experience through their senses and the standard model is one result.Why do you have confidence the standard model if you learned about it through your senses? — Tate

I'd classify them as variations of the sense of touch.There are a lot more senses, which are recognized today as such, beyond the classic 5 ones: balance, weight, motion/movement/kinaesthesia, velocity/speed, spatial/orientation, body position, pressure, vibration, temperature, pain, and more ... — Alkis Piskas

I'd say we have more than the image. We have the idea of a tree which tells us more than an image: tree begin as seeds, they grow slowly, etc. Whenever we learn something new about trees, we revise our idea of them.Well, a tree is not an abstract idea so that we have an idea of it. It is an object, something concrete. So I would say that, independently of its name, i.e. the word "three", it exists in our mind as an image connected to various data (knowledge) we have about it. — Alkis Piskas -

Richard B

569It seems to me phenomenalism is unarguably true. We have five physical senses: sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell. We have no “tree-sensing” sense. So, how can we experience a tree? The answer seems to be we don’t directly experience a tree. Rather, we experience sense data (green patches that feel smooth, brown patches that feel rough, etc.) and our mind accesses the idea of “tree” because the idea makes sense of our sense data. — Art48

Richard B

569It seems to me phenomenalism is unarguably true. We have five physical senses: sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell. We have no “tree-sensing” sense. So, how can we experience a tree? The answer seems to be we don’t directly experience a tree. Rather, we experience sense data (green patches that feel smooth, brown patches that feel rough, etc.) and our mind accesses the idea of “tree” because the idea makes sense of our sense data. — Art48

Lets give an example how you would directly experience a tree. Lets say you would like to determine if it is a tree and what type. The first thing you would need to do is go directly to the tree, directly touch the tree, and directly take a sample of the tree. With this sample you can send it to a lab to test its DNA and see if it is a match to some type of tree. Would you want to say it was a sample of sense data of the tree I sent the lab? No, your sense data is what you have. Would you say the sample is the thing-in-itself? No, this is something we cannot know by our senses. Would you say the sample is part of a tree and you like confirmation? Exactly! -

Christoffer

2.5kCan you give an example of an outside object (without just being programmed to detect what humans already think of as apples) detect apples. I can't think of a single example. — Isaac

Christoffer

2.5kCan you give an example of an outside object (without just being programmed to detect what humans already think of as apples) detect apples. I can't think of a single example. — Isaac

Higgs particle is something we cannot perceive but is detectable in a repeatable fashion by equipment built through theories backed up by mathematical logic.

Human perception cannot explain how this chain of prediction and detection can logically sum up in a factual end point. We can only make the phenomenological point of ourselves not able to perceive the Higgs particle, or perceive the effects it has on mass and temporal movement, but never the object of the particle itself, and we cannot conclude that it doesn't exist because "it's just perception" when logic, predictability, analyzed data, repeatable tests all confirm the particle exists.

The perception of science data does not render the science data wrong just because we perceive the result of those tests. They have no correlation with each other.

science is based on human perception, logic and imagination. So if human perception, logic and imagination are deemed problematic, then so should science be. — Olivier5

Mathematical logic is not based on any human perception. You lump together imagination with logic, but logic is not a human concept. To be able to, through math, predict outcomes of external reality and then confirm that through analytical machines has nothing to do with our perception.

If we build a detector, like the one in CERN, to detect particles we cannot possibly perceive, our perception does not dictate its function, which is what you mean with what you say when you lump in human perception with science.

This is a fundamental misunderstanding of the scientific method, of how science and math works. You are not speaking about our ability to detect external reality past our perception, you are speaking of people making assumptions and assertions out of those results.

That's more close to philosophy than science. Philosophy's role is to speculate, through as much logic as possible, what the facts of the world (science) actually mean for us as human beings. But that is just what it is, philosophy, not science.

This is why the assumption that the phenomenological conclusion of our perception dictating reality is wrong. The correct phenomenological conclusion is that we can only perceive reality in a certain and very specific way and understanding how those limitations of actual reality influence our conclusions of that reality.

Rarely, if ever, have I talked to scientists who make any conclusions past what their data has actually showed them. That's closer to what TV documentaries about science does, they create pretty stupid interpretations of actual science for the effect of entertainment, they have no actual valid conclusions because that would require a dry read-through of the reports and papers published, after all the necessary scrutiny has been applied.

I think this is why people have such a skewed image of what science is and misinterpret it as having too much human input to be valid. That's really not a correct image of how science actually works and knowing the processes that scientists apply to their work just demonstrates the illogical idea of perception dictating reality, that's just a delusional fantasy for humans who want to attribute humans with more power over the universe than they actually have.

Most people cannot grasp the cosmic horror that is our existence in the universe, so we invent interpretations of religious proportions just to cope with the actual reality of our existence. But the truth is that our perception is an extremely limited way of "seeing" the world and the universe... so we build machines to extend our ability to perceive and those machines confirms a reality past ourselves, a reality indifferent to us in every way possible. To think otherwise is just as delusional as when people thought the sun and universe rotated around the earth and us as the center of everything. Everyone is small, insignificant and pointless and it's more or less proven today, regardless of any collective narcissism people delude themselves with otherwise. -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k

It's half the story. While it is undoubtedly true that we "only" perceive our own ideas - something that was taken for granted during the Golden Age of philosophy (from Descartes to Kant, with some minor exceptions like Thomas Reid.), "the way of ideas" is now somehow controversial.

Nevertheless, I think one needs to add either a "substance" of some kind, as articulated specifically by Locke, or "things in themselves" as developed by Kant, and anticipated by others.

We cannot prove that substances in Locke's sense exist, neither Cudworth or Kant's "thing in themselves", it is a posit which gives coherence to the world. It may not exist, but it's problematic if it didn't.

Physics, for instance, has to postulate 95% of the universe as being composed of stuff we cannot detect, or the 5% we do know won't work.

If we don't do this and make such postulates, we are left with the argument that there are appearances, and nothing else. But this would render modern science obsolete: we have this scientific picture which is about appearances, instead of it being about the world.

The last issue here is that, it seems to me to be incoherent to say that there isn't something in the objects that makes us recognize them as objects - other animals seem to treat the world is a similar-ish manner.

The general outline, however, is sound, all it needs is some supplementation. -

Isaac

10.3kHiggs particle is something we cannot perceive but is detectable in a repeatable fashion by equipment built through theories backed up by mathematical logic. — Christoffer

Isaac

10.3kHiggs particle is something we cannot perceive but is detectable in a repeatable fashion by equipment built through theories backed up by mathematical logic. — Christoffer

Good example.

The perception of science data does not render the science data wrong just because we perceive the result of those tests. They have no correlation with each other. — Christoffer

I agree.

...but we were talking about apples. I'm not seeing the logical link between the Higgs Boson being identified by purely mathematically programmed machines and apples.

Your claim was that...

if we and a bunch of aliens, with extremely different perceptions, were to analyze the apple, even with different types of tools, it would still confirm the existence of an object that we could apply definitions to that are descriptive of what we define as an apple. — Christoffer

...that even a machine, an alien, would confirm the existence of an apple. You've shown that machines see Higgs Bosons, but not apples. Apples are collections of these mathematical constructs (quarks and gluons, and all the others I don't know the name of). The properties of fundamental particles are mathematically determined (as you said) the idea that some collection of them ends there and not over there, is not mathematically determined, it's determined by our form of life, our activities, they way we treat and interact with these collections of particles. I don't see an argument that aliens would see the same boundaries as we do when their form of life might be entirely different. -

Banno

30.6kThe interesting thing about Putnam's argument is that it's about meaning, not about ontology, and depends on a causal theory of reference. I think it strange that in such a scenario the brain-in-a-vat cannot refer to itself as being a brain in a vat, and so I think that Putnam's argument is actually a reductio ad absurdum against a causal theory of reference. — Michael

Banno

30.6kThe interesting thing about Putnam's argument is that it's about meaning, not about ontology, and depends on a causal theory of reference. I think it strange that in such a scenario the brain-in-a-vat cannot refer to itself as being a brain in a vat, and so I think that Putnam's argument is actually a reductio ad absurdum against a causal theory of reference. — Michael

I'm inclined to agree as per this particular argument. However the sentiment behind the argument, the rejection of radical scepticism by showing that it undermines itself, remains. Neo was evicted from his pod, and hence there is a world in which there is a pod. For the brain in the vat, there is a vat. The phenomenalist conclusion, that

fails because the pod and the vat are not just "theoretical constructs".So, it seems material objects are actually theoretical constructs — Art48 -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

So we repeat the mantra "It's got science behind it" in the place of thinking?

The debate between direct and indirect realism was settled a ways back in favour of dropping the distinction. Austin won. @Richard B has been doing a reasonable job of presenting that account. -

Tate

1.4kSo we repeat the mantra "It's got science behind it" in the place of thinking? — Banno

Tate

1.4kSo we repeat the mantra "It's got science behind it" in the place of thinking? — Banno

You misunderstand. It's not a view I favor or dislike. I'm just explaining where we are.

The debate between direct and indirect realism was settled a ways back in favour of dropping the distinction. — Banno

Could be. Nevertheless, indirect realism is on the table. Ignoring it won't help. -

Richard B

569Indeed, Russell, in The Problems of Philosophy, says the following after talking about difficulties that arises with his analysis of senses: “Thus it becomes evident that the real table, if there is one, is not the same as what we immediately experience by sight or touch or hearing. The real table , if there is one, is not immediately known to us at all, but must be an inference from what is immediately known.”

Richard B

569Indeed, Russell, in The Problems of Philosophy, says the following after talking about difficulties that arises with his analysis of senses: “Thus it becomes evident that the real table, if there is one, is not the same as what we immediately experience by sight or touch or hearing. The real table , if there is one, is not immediately known to us at all, but must be an inference from what is immediately known.”

I believe the transition from his analysis of senses to his conclusion is not evident. But for the Indirect Realist, this may be the area to clarify to help their position. -

Banno

30.6k— Banno

Banno

30.6k— Banno

an analysis of our nervous systems leads straight to that conclusion. — Tate

Depends on what one understands by "direct".

As discussed at length with @Isaac, who knows about such things, one does not see the results of one's nervous system, as it where; one sees with one's nervous system.

So when one looks at a tree or a cup or some such standard item, there is a narrative that says that what one sees is not the tree but the product of one's eyes and optical nerves and so on. But that's a mistaken narrative. What one sees is the tree, and these are seen using one's eyeballs and optical nerves and so on.

And this is the usual sense in which 'indirect realism" is misused; that science shows that we never see the tree directly. It's often case of Stove's Gem.

That's one case. There are others, in which indirect realism becomes a form of antirealism or worse, idealism.

The arguments are detailed, and get lost in the noise of the forums. -

Tate

1.4kone does not see the results of one's nervous system, as it where; one sees with one's nervous system — Banno

Tate

1.4kone does not see the results of one's nervous system, as it where; one sees with one's nervous system — Banno

I'd like to leave the "one who sees" out of it because I think the ego is probably constructed as much as the visual field is.

Point is, the brain isn't a video recorder, it's more like an organic computer, calculating and estimating. -

Banno

30.6kPoint is, the brain isn't a video recorder, it's more like an organic computer, calculating and estimating. — Tate

Banno

30.6kPoint is, the brain isn't a video recorder, it's more like an organic computer, calculating and estimating. — Tate

Predicting, as I understand it.

None of which implies that we see things only indirectly.

Better, drop the notion of direct and indirect and just say we see the tree.

Then the realism/antirealism discussion can move back to choosing between a logic in which there are unknown truths and one in which there are not.

Here's an example I gave elsewhere. On the table is a cup with one handle. The realist and the idealist agree that "the cup has one handle" is true.

In the cupboard is another cup. The realist says "The cup has one handle" is true. The idealist says "the cup has one handle" does not have a truth value.

In the end the musings here come down to a choice between which logic it is appropriate to apply to our situation. — Banno -

Tate

1.4kNone of which implies that we see things only indirectly. — Banno

Tate

1.4kNone of which implies that we see things only indirectly. — Banno

It's what we would say of any other species, that its experience is a construction in which its particular strengths and needs are highlighted.

Yes, I run into a problem when I try to say the same thing about myself: as Wittgenstein pointed out, I'm trying to form a picture of something that isn't in my world. I think that's why nonsense appears.

You're saying the solution is to finesse the conundrum with a certain phrasing that leaves out the nonsense producing portion?

Why not just face the nonsense head on? -

Banno

30.6kYou're saying the solution is to finesse the conundrum with a certain phrasing that leaves out the nonsense producing portion?

Banno

30.6kYou're saying the solution is to finesse the conundrum with a certain phrasing that leaves out the nonsense producing portion?

Why not just face the nonsense head on? — Tate

Same thing. Dissolving philosophical problems often (always?) consists in finding the better way to say something, of looking at the problem differently, -

Isaac

10.3kBetter, drop the notion of direct and indirect and just say we see the tree. — Banno

Isaac

10.3kBetter, drop the notion of direct and indirect and just say we see the tree. — Banno

By far the best solution. The matter of how we see is being confused with the matter of what we see.

Folk seem confused by the idea of active inference into thinking that the subject of perception must therefore be in the mind, but this could not be further from what active inference is saying. It is, quite literally, predicated on the idea that the subject of our inference hierarchies (the process of seeing being one such) is the external hidden states, not the internal ones. The entire mathematical structure of active inference - from Fokker-Plank equations though gradient climbing formulations to the famous Bayesian model error functions - would simply fail if it were not assumed that the external world were the subject of the process. There'd be no gradient to climb (no external world forces to resist the decay to Gaussian distribution from). -

Olivier5

6.2kYou lump together imagination with logic, but logic is not a human concept. — Christoffer

Olivier5

6.2kYou lump together imagination with logic, but logic is not a human concept. — Christoffer

Logic is a very human concept. Maybe you mean to say that logic is not limited to humans, which I would agree with.

If we build a detector, like the one in CERN, to detect particles we cannot possibly perceive, our perception does not dictate its function, which is what you mean with what you say when you lump in human perception with science.

I think you would agree that a group of blind and deaf people could not build and operate the CERN accelerator. Even if they could, how would they know what the results of their experiments are?

We can build tools to expand on our senses but someone still needs to look into the telescope. With one's eyes. -

Christoffer

2.5k...but we were talking about apples. I'm not seeing the logical link between the Higgs Boson being identified by purely mathematically programmed machines and apples. — Isaac

Christoffer

2.5k...but we were talking about apples. I'm not seeing the logical link between the Higgs Boson being identified by purely mathematically programmed machines and apples. — Isaac

If you can prove the existence of an object like the Higgs particle then you can logically prove the existence of a larger object that we humans refer to as "an apple" through the same methods of testing and using instruments that bypass our perception. We can provide all the data about the apple that confirms it to be that kind of an object, based on how it correlates with what our perception tells us. We can also further test our perception with having a large sample size of people going into a room and then out and then describing the object in there and then use that data from a thousand different individuals to confirm that we have a collective perception of the object as an apple, then compare that to the scientific data from the instruments to conclude the existence of the object both outside our perception as well as through our perception.

It's basically "Mary in the black and white room". The black and white data is the external, the emotional experience of the outside is the perception of humans.

Logic is a very human concept. Maybe you mean to say that logic is not limited to humans, which I would agree with. — Olivier5

That we discovered, invented or stumbled upon a logical system that we merely give a name and wrap uses around does not mean the concept in itself is human. Mathematical logic is, for example, universal. It doesn't matter how our perception is, it never changes such logic, only the interpretation of that logic is based on perception.

I think you would agree that a group of blind and deaf people could not build and operate the CERN accelerator. Even if they could, how would they know what the results of their experiments are?

We can build tools to expand on our senses but someone still needs to look into the telescope. With one's eyes. — Olivier5

We are still blind and deaf to the existence of a Higgs particle, or the concept of its function is still so alien to us that we cannot perceive it as a function of reality. That doesn't mean the detector doesn't detect the particle.

The data is not dependent on our interpretation, it's dependent on logic. If the detector finds a particle characterized by the mathematical prediction of its function and the detector confirms this particle in existence, it doesn't matter what perception or level of perception we have as humans. A blind person will be able to understand the data just as well as a seeing person since there's nothing to see or perceive, it's the machine that sees the particle and tells us that it matches our prediction made through logic. In no part of this process is there any human perception that defines the detection of the particle. The perception you describe is reading the conclusion on a screen at CERN or conceptualizing the meaning of the particles existence outside of the scientific logic behind the detection of it.

But the bottom line is still that there is a reality that exists past our human perception and that the only clear use of phenomenology is to guide our philosophical thinking of how we perceive reality versus how reality actually is. Like how light consists of wavelengths that we use every day in the form of radio, radar and x-rays, but we can only see a fraction of these wavelengths with our eyes. -

Michael

16.8kI'm inclined to agree as per this particular argument. However the sentiment behind the argument, the rejection of radical scepticism by showing that it undermines itself, remains. Neo was evicted from his pod, and hence there is a world in which there is a pod. For the brain in the vat, there is a vat. The phenomenalist conclusion ... fails because the pod and the vat are not just "theoretical constructs". — Banno

Michael

16.8kI'm inclined to agree as per this particular argument. However the sentiment behind the argument, the rejection of radical scepticism by showing that it undermines itself, remains. Neo was evicted from his pod, and hence there is a world in which there is a pod. For the brain in the vat, there is a vat. The phenomenalist conclusion ... fails because the pod and the vat are not just "theoretical constructs". — Banno

The brain-in-a-vat and other such hypotheses are just analogies. The underlying principle is best exemplified by Kant's transcendental idealism. There is indeed something that is the cause of experience, but given the logical possibility of such things as the brain-in-a-vat hypothesis, it is not a given that everyday experiences show us the cause of experience. The causal world might be very unlike what is seen. And that includes being very unlike the material world as is understood in modern physics. So it's not that we could just be some brain-in-a-vat, it's that we could just be some conscious thing in some otherwise ineffable noumena.

At the very least this might warrant skepticism (in the weaker sense of understanding that we might be wrong, not in the stronger sense of believing that we're likely wrong). However, it might not warrant phenomenalism. That we can't know that the causal world is like the world we experience isn't that the causal world isn't like the world we experience. Something more than just the skepticial hypothesis is required to defend phenomenalism.

Regarding this latter point, let's say that there are two possible worlds, one which is phenomenalist (e.g. Kant's transcendental idealism obtains) and one which is direct realist. Unless such a scenario necessarily entails that the character of their inhabitants' experiences differ, skepticism is warranted in both the phenomenalist world and the direct realist world (none of the inhabitants can know which of the two worlds they live in), but phenomenalism is false in the direct realist world (and direct realism is false in the phenomenalist world).

So what we need to discuss is the assumption made in this hypothesis. Would the character of one's experiences in a phenomenalist world differ from the character of one's experiences in a direct realist world? If so, what character would we expect in each, and which of these (if either) is the character of our experiences?

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum