-

Pie

1k

Pie

1k

It seems obvious that for every true contingent proposition there must be something in the world (in the largest sense of “something”) which makes the proposition true. For consider any true contingent proposition and imagine that it is false. We must automatically imagine some difference in the world.

I think folks are falling prey to their visual imagination somehow. If the contingently true proposition is the color of Sally's dog, they visually imagine the color being changed, digging beneath propositions to 'sense-data.' This is the ice box temptation too. They 'see' the plums. They are trying to methodically ignore the conceptual aspect of experience, as if pre-conceptual visual memory were the truly real...and articulation was a secondary layer.

Cartesian baggage. As if epistemology makes sense as a merely private matter.

Or that's my hypothesis. -

Banno

30.6kWe will disagree as to whether Davidson's ideas flow parallel with Wittgenstein, if you mean by parallel, there is agreement. Just from the little I read in the SEP, I don't get that idea. There are other philosophers who do a much better job of extending Wittgenstein's ideas. — Sam26

Banno

30.6kWe will disagree as to whether Davidson's ideas flow parallel with Wittgenstein, if you mean by parallel, there is agreement. Just from the little I read in the SEP, I don't get that idea. There are other philosophers who do a much better job of extending Wittgenstein's ideas. — Sam26

Parallel lines don't touch...

Here's Truth and Meaning.Let me know what you think. Davidson takes on questions unaddressed by Wittgenstein. -

Banno

30.6kI don't understand you. No one is talking about escaping truth. — hypericin

Banno

30.6kI don't understand you. No one is talking about escaping truth. — hypericin

Well, then, what are you claiming? Back to this:

P cannot be the same thing as P is true. — hypericin

The main function in a T-sentence is the truth functional operator "≡", not "=". So indeed, p is not the same thing as "p is true". -

Banno

30.6kSo...

Banno

30.6kSo...

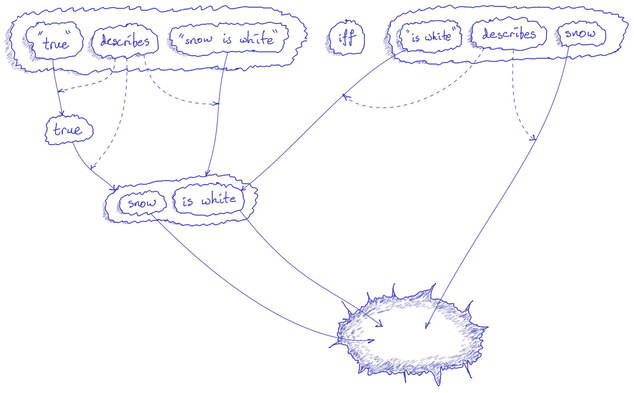

'there are plums in the icebox' is true if and only if there are plums in the icebox.

Presumably - and here I am just trying out the apparent idea of a truthmaker - 'there are plums in the icebox' is made true by there being plums in the icebox... and so the notion of being is introduced, and we fall down a well of ontology.

That's progress?

I'm still not seeing it. -

Luke

2.7kFor isn't this just a complicated way of saying that P is the truthmaker of 'P' ? But nothing is actually being added. No truth is being made. P is just (taken as) true. — Pie

Luke

2.7kFor isn't this just a complicated way of saying that P is the truthmaker of 'P' ? But nothing is actually being added. No truth is being made. P is just (taken as) true. — Pie

I’d just like to maintain some separation between the way things are in the world and our statements about the way things are in the world, because we might consider some of those statements to be false. It may be redundant whether we say either “P” or “P is true” (iff “P” is true), but it is not redundant to distinguish between P and “P”. -

Tom Storm

10.9kFWIW, I think it's hard to divorce rationality from anti-racism, anti-sexism, and anti-classism. It goes with free speech, democracy, and science. — Pie

Tom Storm

10.9kFWIW, I think it's hard to divorce rationality from anti-racism, anti-sexism, and anti-classism. It goes with free speech, democracy, and science. — Pie

Thanks for your answers to my earlier question. This one strikes me as somewhat tendentious. To me this position - which I generally share - seems to originate from a value system which already holds that reason and progressive politics are synonymous, or flip sides of the same coin. How does one make this case in philosophic terms? Rationality can also be mustered successfully to support conservative and libertarian positions, right? What process do we use to determine if a rational framework is being put to work appropriately, other than following the arguments back down to foundational value systems and agreeing or disagreeing with those? -

Luke

2.7kI never could see much of use in the notion of truthmakers. Can either of you explain what they are for? — Banno

Luke

2.7kI never could see much of use in the notion of truthmakers. Can either of you explain what they are for? — Banno

I’m not sure whether I’m using the term in accordance with truthmaker theory; I used it only as an expedient for “that which determines whether a statement is true or false”. A quick search seems to indicate this use is pretty much the same as the truthmaker theory. -

Banno

30.6kThanks.

Banno

30.6kThanks.

Heres' my problem: what sort of thing is "that which determines whether a statement is true or false"?

Because I think it clear that if anything determine that "The plums were in the icebox" is true, it's that plums are in the icebox.

One feels like saying that "what makes the statement true is..." And here one wants to finish with "the statement itself", but that is wrong; or perhaps one might finish with "what the statement says", or "the fact it presents", or some such; and none of these tell us anything.

So it looks to me more like there is a problem with supposing a something which determines that the statement is true or false; an unneeded reification.

The urge to posit a "that which determines whether a statement is true or false" is the urge towards substantive, ie, non-deflationary, accounts of truth. -

Banno

30.6kI’d just like to maintain some separation between the way things are in the world and our statements about the way things are in the world, because we might consider some of those statements to be false. It may be redundant whether we say either “P” or “P is true” (iff “P” is true), but it is not redundant to distinguish between P and “P”. — Luke

Banno

30.6kI’d just like to maintain some separation between the way things are in the world and our statements about the way things are in the world, because we might consider some of those statements to be false. It may be redundant whether we say either “P” or “P is true” (iff “P” is true), but it is not redundant to distinguish between P and “P”. — Luke

But is there a need to maintain a separation between the way things are in the world and our true statements about the way things are in the world?

Seems to me that there is not.

And it seems to me that this is what Davidson is saying in suggesting we give up our dependence on the concept of an uninterpreted reality: that there is no such separation between our true statements and the way things are. We "reestablish unmediated touch with the familiar objects whose antics make our sentences and opinions true or false".

(@Sam26) -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Seems to me that this is an attempt to explain truth in terms of "describe" or "denote".

That's problematic, since firstly "is true" looks clearer than either "denotes" or "describes", and secondly we can ask if it is true that this "describes" or "denotes" that, and hence already need the notion of truth in order to understand denotation and description....

Here's the thing, and the same point as I was trying to make for @Isaac; that in order to have this discussion we make assertions, and in order to make assertions, we make use of truth; hence truth is fundamental to our discussions in. a way that renders it not a suitable subject for our discussions.

Put another way: there can be no substantive definition of truth. -

Pie

1kFair questions indeed! I'm self-consciously just a dude, a non-parent even, who likes to talk about ideas...and I feel my smallness. With that disclaimer, I open my big mouth and try again.

Pie

1kFair questions indeed! I'm self-consciously just a dude, a non-parent even, who likes to talk about ideas...and I feel my smallness. With that disclaimer, I open my big mouth and try again.

To me this position - which I generally share - seems to originate from a value system which already holds that reason and progressive politics are synonymous, or flip sides of the same coin. — Tom Storm

How does one make this case in philosophic terms? — Tom Storm

Maybe 'progressive' is a little too loaded here in our polarized times, though it's typically been on the side of enfranchisement. I'd stress freedom/autonomy. Freedom/automony means being bound by norms that one understands and embraces, establishing one's own laws. If we think in terms of justification...of the right to and the habit of asking why we should obey or believe, plausibly implicit in freedom/autonomy, then we see that reason is 'given' or basic.

'Why should I be reasonable ?' asks for a reason. Brandom might stress that we just are inferential animals. That's what 'rational' means.

It is requisite to reason’s lawgiving that it should need to presuppose only itself, because a rule is objectively and universally valid only when it holds without the contingent, subjective conditions that distinguish one rational being from another.

...

...

Reason must subject itself to critique in all its undertakings, and cannot restrict the freedom of critique through any prohibition without damaging itself and drawing upon itself a disadvantageous suspicion. For there is nothing so important because of its utility, nothing so holy, that it may be exempted from this searching review and inspection, which knows no respect for persons [i.e. does not recognize any person as bearing more authority than any other—GW]. On this freedom rests the very existence of reason, which has no dictatorial authority, but whose claim is never anything more than the agreement of free citizens, each of whom must be able to express his reservations, indeed even his veto, without holding back. (A738f/B766f, translation slightly modified) — Kant

The second part is trickier, because dominant humans (with worldly power anyway) have withheld adult status (freedom and autonomy) from other human beings for various reasons. I take Hegel's work to be largely about the expansion of this rational tribe toward the realization that all humans are free. Is this expansion implicit in reason ? I think it basically is, though not obviously so. The big thing I learned from philosophy was the primacy of the social. I am a 'we' before I am an 'I.' To speak a language is to run an inherited operating system, to share an always already significant lifeworld. This 'softwhere' doesn't need or care about this or that skin color or sex organ (which doesn't mean it can't be initially confused about this independence.) The developing individual primarily assimilates ideas and skills that he himself did not create. Robust and glorious individuality abases itself to be exalted, empowers itself by surrendering itself to others, listening to and learning from everyone else, submitting to the better reason, thereby transforming humiliation and error into strength. I think it was Bacon who insisted that we are the ancients, because we inherit more than all who came before us. It's as if human knowledge, call it Shakespeare, is a baby god getting fat on centuries of experience, surviving the death of his cells, we the thinkers and tinkers and stinkers who come and go, picking up tricks upon entrance and sometimes leaving behind a few before exiting. The gut level version of this is described by Ma Joad. There's just one momma's love that all us mammals share in...and maybe there's just one 'intellectual love of God' which I can celebrate as a Spinoza-adjacent atheist with you and everyone else. Is it our nature to expand and transcend ourselves ? Unless something jams us up?

Rorty didn't trust theories of human nature, but I'm not afraid to keep trying to make explicit what we are, wary of course of abuses of the phrases 'human nature' and 'rationality.' Yet I'm not optimistic. We might indeed destroy ourselves, descend into another holocaust or worse. I can even feel my way into the antinatalist who is terrified of life's shameful vulnerability and would like us all safely extinct. I was moved by David Pearce's ideas. How glorious for a product of the nightmare of Darwinian evolution to correct that nightmare, if such a project is not insane. I'll settle for Denmark at the moment. In fact, I'm seem to be fairly happy with my own life in the insane US. -

Pie

1kAnd it seems to me that this is what Davidson is saying in suggesting we give up our dependence on the concept of an uninterpreted reality: that there is no such separation between our true statements and the way things are. We "reestablish unmediated touch with the familiar objects whose antics make our sentences and opinions true or false". — Banno

Pie

1kAnd it seems to me that this is what Davidson is saying in suggesting we give up our dependence on the concept of an uninterpreted reality: that there is no such separation between our true statements and the way things are. We "reestablish unmediated touch with the familiar objects whose antics make our sentences and opinions true or false". — Banno

:up:

It can come to look obvious even. Of course! -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kour tribal conceptual norms — Pie

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kour tribal conceptual norms — Pie

Not one of those paid private teachers, whom the people call sophists and consider to be their rivals in craft, teaches anything other than the convictions that the majority expresses when they are gathered together. Indeed, these are precisely what the sophists call wisdom. It's as if someone were learning the moods and appetites of a huge, strong beast that he's rearing—how to approach and handle it, when it is most difficult to deal with or most gentle and what makes it so, what sounds it utters in either condition, and what sounds soothe or anger it. Having learned all this through tending the beast over a period of time, he calls this knack wisdom, gathers his information together as if it were a craft, and starts to teach it. In truth, he knows nothing about which of these convictions is fine or shameful, good or bad, just or unjust, but he applies all these names in accordance with how the beast reacts—calling what it enjoys good and what angers it bad. He has no other account to give of these terms. And he calls what he is compelled to do just and fine, for he hasn't seen and cannot show anyone else how much compulsion and goodness really differ. — Republic 493a-c

This talk of norms, is it an advance on Plato, or is it sophistry in modern, perhaps even scientific garb?

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum