-

khaled

3.5kI will now present my ontological view for everyone to have fun tearing down. I don't know if this ontology has a name already but if it does please tell me.

khaled

3.5kI will now present my ontological view for everyone to have fun tearing down. I don't know if this ontology has a name already but if it does please tell me.

It is a dualist ontology, but not substance (ew), or property dualism. I believe that what exists is matter, and patterns of matter.

A pattern is not a material thing. Think of a sin wave. You will never find a sin wave in nature. You may find things that have the rough shape of a sin wave, but never the pattern of a sign wave itself. Sort of like Plato's forms. Difference being that there is no heirarchy of patterns, and no "pattern of patterns". Patterns can also be seen as collections of properties. The difference from property dualism is that there patterns are neither "mental" nor "physical".

One material thing can have many patterns, but not any combination of patterns is possible (no square triangles). Also, patterns can contain other patterns, like how quadrilaterals contain squares. Material things are always instantiations of certain patterns. So a box is an instantiation of a hollow cube. Instantiations never perfectly match the pattern.

In this view, consciousness is a specific range of patterns of matter. When the pattern of our bodies is disturbed enough (such as in sleep, or death) we leave the range where we would be considered conscious. The range is rather fuzzy when you take into consideration drugs and half-asleep states, etc. Emotions and experiences are also patterns of matter. But again, we seem to have loose definitions to all of these things for now.

When someone says something is caused by a pattern they mean that it was caused by the material instantiation of the pattern. For example: "I hit him because I was angry" means that the pattern of "anger" when instantiated in the form of flesh and blood (assuming the speaker is human), resulted in a physical movement that roughly matches the pattern "hit". So patterns aren't present in the causal chain, but are still extremely important for causation (if the person in the above example had the pattern "happy" instead he probably wouldn't have hit anyone)

Patterns aren't limited to the ones we find. The pattern of a quadrliatiral would exist even if no one discovered shapes with 4 sides.

Some consequences to popular problems:

1- No mind body problem. When someone says a physical thing was caused by a "mental" thing it means that the physical thing was caused by the material instantiation of the pattern that is the mental thing.

2- BUT minds and bodies are still fundamentally different and irreducible to each other, best of both worlds! Minds are patterns and bodies are matter.

3- Anything can be conscious, not just humans. We will figure out how things are conscious just as soon as we precisely define what the pattern "conscious" means (which doesn't seem to be happening any time soon).

4- Free will exists. Since "we" are the patterns that our bodies are instantiated from, we "cause" (defined above) our actions. So there is also room for moral accoutnability and ethics.

5- If a teleporter evaporated all of your particles and reassebled you again very far away it would still be you because "you" is the pattern, not the particles. And if you were not evaporated there would be two idnetical "yous". Also other sci-fi cliches such as "upload my consciousness to the net" make sense in this view. -

khaled

3.5kPatterns aren't limited to the ones we find. The pattern of a quadrliatiral would exist even if no one discovered shapes with 4 sides. — khaled

khaled

3.5kPatterns aren't limited to the ones we find. The pattern of a quadrliatiral would exist even if no one discovered shapes with 4 sides. — khaled

All patterns exist independently of anything.

Also your question would be akin to "Can patterns exist independently of pattern A" since minds are patterns in my view.

patterns of matter — RussellA

Also, since there are no patterns of patterns, and there is only patterns and matter, then this would be a useless distinction in my view. patterns can ONLY be of matter, they can't be of anything else. -

RussellA

2.6kAll patterns exist independently of anything. — khaled

RussellA

2.6kAll patterns exist independently of anything. — khaled

A pattern is a repeated relationship between its parts. If there was no relation between the parts, then the pattern wouldn't exist.

For patterns to exist, relations must exist. How do you justify the belief that relations exist, ie, that relations ontologically exist. -

khaled

3.5kIf there was no relation between the parts, then the pattern wouldn't exist. — RussellA

khaled

3.5kIf there was no relation between the parts, then the pattern wouldn't exist. — RussellA

What exactly does "no relation" mean when it comes to material things? Let's take the pattern "on top of". Any 2 material things can be on top of each other as long as we specify a direction. If I stack 2 boxes they are on top of each other. If I set one down next to the other, then they are no longer on top of each other, but now they fit the pattern "next to".

My point being that since material things have a location, they are always related at least when it comes to their locations relative to each other. I don't see how 2 material things can have no relation whatsoever, no pattern that they fit.

Even "located 32 kilometers away from each other" is a pattern for example, one many pairs of things emobdy no less, just one that we haven't deemed useful enough to make a word for.

How do you justify the belief that relations exist, ie, that relations ontologically exist. — RussellA

But I'm curious what made you ask in the first place. Why would justifying the existence of relations be a task for my view specifically? How would a materialist or substance dualist justify it for example? Seems like such a building block concept. -

RussellA

2.6kWhy would justifying the existence of relations be a task for my view specifically? — khaled

RussellA

2.6kWhy would justifying the existence of relations be a task for my view specifically? — khaled

It wouldn't be if "patterns of matter" existed only in the mind, but you also say that "All patterns exist independently of anything", and " The pattern of a quadrilateral would exist even if no one discovered shapes with 4 sides", inferring that patterns also exist in a mind-independent world.

I agree that all material things have a location, and when we observe material things we can observe a relation between them, so relations do exist in the mind. So, patterns exist in the mind.

But how do we know that the relation we believe we observe between material things in the world

doesn't actually exist in the world , but is, in a sense, a projection of our mind onto the world. And if relations don't exist in a mind-independent world, then neither do patterns exist in a mind-independent world.

I'm thinking about the problem of "relations" as described in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Relations, which discusses (1) Rejection of both properties and relations. (2) Acceptance of properties but rejection of relations. (3) Acceptance of relations but rejection of properties. (4) Acceptance of both properties and relations. -

khaled

3.5kBut how do we know that the relation we believe we observe between material things in the world

khaled

3.5kBut how do we know that the relation we believe we observe between material things in the world

doesn't actually exist in the world , but is, in a sense, a projection of our mind onto the world. — RussellA

A proof by contradiction.

There have been many times where there existed relations between material objects that we did not detect, but were nevertheless there. For example: The relation "Have a gravitational pull towards each other" has always been in effect, even before we detected it. Every physical law has always existed even before we detected it, and every physical law fits the definition of a pattern (which is why we can represent it mathematically).

So by example, we can see that patterns exist, and are in effect (have an instantiation) before we find them all the time. So how could patterns be projections of our mind only?

Not every pattern we think of represents reality, but that does not mean that every pattern we think of is merely a mind-dependent projection.

Besides that, I think there is a misunderstanding of my position. I believe ALL possible patterns exist, even if there is no material instantiation of them, and even if we haven't thought of them. So in a world without spheres, the pattern of "sphere" would still exist, even if no one imagined it yet. That is because I believe that patterns are fundamentally found, not created. Though, I suspect "all possible patterns exist" vs "only patterns that have a material instatiation exist" is an inconsequential difference ultimately. The proof by contradiction proves the latter not the former.

PS: By "possible" pattern I mean not self-contradictory, like a square triangle. -

unenlightened

10kI prefer "stuff" to "matter", and I prefer "arrangement" to "pattern" because a pile of sand is matter arranged in no particular pattern, and light and X rays and such is something, but not quite matter to my mind. And when pressed, I will try to squeeze in "process" as a sequence of patterns.

unenlightened

10kI prefer "stuff" to "matter", and I prefer "arrangement" to "pattern" because a pile of sand is matter arranged in no particular pattern, and light and X rays and such is something, but not quite matter to my mind. And when pressed, I will try to squeeze in "process" as a sequence of patterns.

As to the existence of patterns without matter as 'potential arrangements' or what have you, you can please yourselves as to their 'existence'. Certainly mathematics studies such beasts in the abstract, whether they exist or not. -

180 Proof

16.4k

180 Proof

16.4k

Sounds to me like what neo-Scholastics call "hylomorphism".I don't know if this ontology has a name already but if it does please tell me.

It is a dualist ontology, but not substance (ew), or property dualism. I believe that what exists is matter, and patterns of matter. — khaled -

punos

796I believe that what exists is matter, and patterns of matter. — khaled

punos

796I believe that what exists is matter, and patterns of matter. — khaled

Would it not be better to say that "what exists is energy (what matter is or is made of), and information (pattern). Matter is patterned energy, or in other words energy infused with information."?

All that really exists is energy; pattern or information emerges from the self-interacting chaotic nature of energy. A simple analogy would be to say that energy is to the ocean as information or pattern is to the waves. Energy is responsible for quanta or magnitude of existence in the universe while pattern represents configurations of quanta responsible for quality in the universe.

Energy is hard to define but i conceive of it as being both force and substance in and of itself. Force is the active principle of energy which is responsible for time (the hand of energy) and substance is the passive principle responsible for space (the memory of energy). These two characteristics of energy together in turn produce information patterns we know as matter, and matter evolves and increases in complexity through the process of evolution.

If one considers 'time and space' analogous to 'process and memory' then one can consider time and space to be components of a cosmic or universal mind, while all the things in the universe represent thoughts of this mind just processing information. Makes me wonder if a "thing" is just another word for a "think" of the universe (mind). -

khaled

3.5kI prefer "stuff" to "matter", and I prefer "arrangement" to "pattern" — unenlightened

khaled

3.5kI prefer "stuff" to "matter", and I prefer "arrangement" to "pattern" — unenlightened

Yea that sounds better. -

RussellA

2.6kThe relation "Have a gravitational pull towards each other" has always been in effect, even before we detected it. Every physical law has always existed even before we detected it, and every physical law fits the definition of a pattern (which is why we can represent it mathematically). — khaled

RussellA

2.6kThe relation "Have a gravitational pull towards each other" has always been in effect, even before we detected it. Every physical law has always existed even before we detected it, and every physical law fits the definition of a pattern (which is why we can represent it mathematically). — khaled

Patterns and relations exist in the mind of an observer of a mind-independent world

The Moon circled the Earth before humans existed, and in our terms, there was a pattern in how the Moon circled the Earth and there was a relation between the Moon and the Earth.

A pattern needs a relation between parts. I agree that patterns and relations exist in the mind, but do patterns and relations exist in a mind-independent world, because it affects your thesis that " I believe that what exists is matter, and patterns of matter".

Force is a different concept to relation, in that there may be a temporal relation between two masses yet no force between them. Two masses on either side of the Universe will have a spatial relation yet there be no force between them. There may be a relation between a mass and my concept of the mass yet no force between them. Force should be treated differently to relation.

My belief is that patterns and relations don't exist in a mind-independent world, for the reason that there is nowhere for them to exist.

Consider a system of two masses each experiencing a force as described by the equation F = Gm1m2/r2, the equation of universal gravitation. Mass m1 moves because of a force due to m2, and in our terms there is a relation between m1 and m2 and there is a pattern in the movement of m1 expressed by the equation.

Consider mass m1 experiencing a force. An external observer may know that the force on m1 is due to mass m2 at distance r, yet no observer could discover from an internal inspection of m1 that the force it was experiencing was due to m2 at distance r. Problem one is that the force from a 1kg mass at 1m would be the same force as a 4kg mass at 2m, giving an infinite number of possibilities. Problem two is that mass m1 can only exist at one moment in time, meaning that no information could be discovered within it as to any temporal or spatial change it may or may not have experienced.

Similarly, no internal inspection of m2 could discover any relation with m1. Similarly, no internal inspection of the force on m1 could discover any relation with mass m2, and no internal inspection of the force on m2 could discover any relation with mass m1. No observation internal to the m1, m2 system could discover any relation between m1, m2 and the force between them. Relations cannot be discovered intrinsic to the system m1, m2 because relations don't exist intrinsic to the system m1, m2.

An outside observer of the system m1, m2 may discover the relation F = Gm1m2/r2 because the relation is extrinsic to the system m1,m2. An extrinsic observer of the system m1, m2 would be able to relate the movement of m1, m2 to a force between them determined by the equations F = Gm1m2/r2 and F = ma. The observer would be aware of a relation between m1, m2, and being aware of a relation would be aware of a pattern.

As the relation F = Gm1m2/r2 is not intrinsic to the system m1, m2, by implication, the laws of nature are not intrinsic in a mind-independent world. Similarly, as the relation F = Gm1m2/r2 may be discovered by an outside observer of the system m1, m2, by implication, the laws of nature being extrinsic to a mind-independent world exist in the mind of an observer.

In summary, relations and patterns are extrinsic to a mind-independent world, and exist in the mind of someone observing a mind-independent world. -

khaled

3.5kTwo masses on either side of the Universe will have a spatial relation yet there be no force between them. — RussellA

khaled

3.5kTwo masses on either side of the Universe will have a spatial relation yet there be no force between them. — RussellA

Yes there is, gravitational. And seeing how most physical stuff has a mass, I cited gravitational pulls as a relation that's present between most physical stuff and most other physical stuff. But this is a minor point.

My belief is that patterns and relations don't exist in a mind-independent world, for the reason that there is nowhere for them to exist. — RussellA

In a dualist conception, minds don't occupy a location either, but that's hardly proof they don't exist, especially not to the dualist. Even in materialist philosophies there are things that don't occupy a location. Very small particles do not occupy a single location as shown by the double slit experiment.

And also doesn't this contradict:

The Moon circled the Earth before humans existed, and in our terms, there was a pattern in how the Moon circled the Earth and there was a relation between the Moon and the Earth. — RussellA

There couldn't have been a relation between the moon and the earth before humans existed if minds are required for relations to exist.

No observation internal to the m1, m2 system could discover any relation between m1, m2 and the force between them — RussellA

And YET

there is a relation between m1 and m2 and there is a pattern in the movement of m1 expressed by the equation. — RussellA

EVEN IF no one is able to figure out why. If minds were required for a pattern's existence, then how come m1 and m2 are already acting in accordence to a pattern even before anyone finds (or "creates") it?

Relations cannot be discovered intrinsic to the system m1, m2 because relations don't exist intrinsic to the system m1, m2. — RussellA

Similarly, as the relation F = Gm1m2/r2 may be discovered by an outside observer of the system m1, m2, by implication — RussellA

"Discovered". In order for something to be discovered, it must exist first no? The pattern exists in the system: {m1, m2}, even if it doesn't exist in the system {m1} or the system {m2}

In summary, relations and patterns are extrinsic to a mind-independent world, and exist in the mind of someone observing a mind-independent world. — RussellA

Let's test this hypothesis.

1: Minds are required for relations to exist (If I'm misinterpreting your position please tell me)

2: Therefore without minds relations would not exist

3: Therefore relations did not exist before human minds existed

4: Therefore the movement of the moon was in no way related to the movement of the earth before human minds existed

5: 4 is false, therefore the assumption 1 must be false. -

RussellA

2.6kIn order for something to be discovered, it must exist first no? — khaled

RussellA

2.6kIn order for something to be discovered, it must exist first no? — khaled

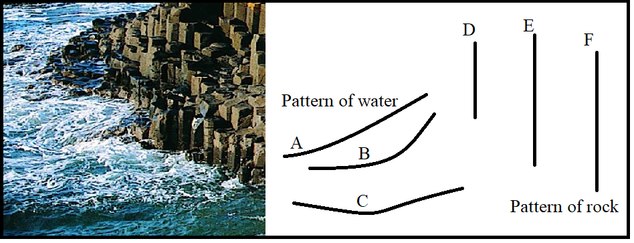

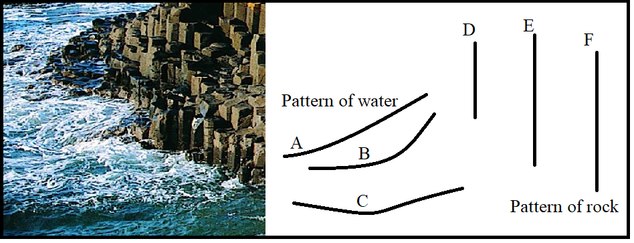

When we observe the Giant's Causeway, which existed before sentient observers, we discover a pattern in the relationship of the parts.

It is in the nature of sentient beings to discover patterns in what they observe, and it may well be that different sentient beings discover different patterns from the same observation.

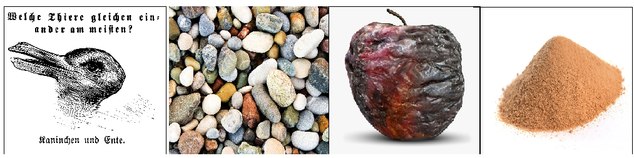

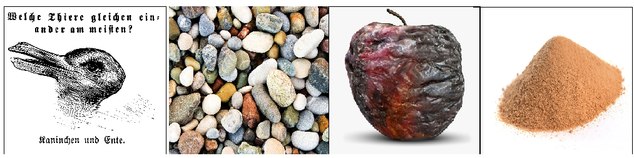

That you discover a duck and I discover a rabbit in the same picture does not mean that either exists in what is being observed.

When we discover a pattern or a relation, we are discovering an inherent part of human nature, not something that ontologically exists in a mind-independent world.

-

khaled

3.5kwe discover a pattern in the relationship of the parts. — RussellA

khaled

3.5kwe discover a pattern in the relationship of the parts. — RussellA

Which would require the parts to have a relationship, or for us to be mistaken about a pattern. That's actually another argument now that I think about it. Mistakes in patterns.

When someone says something like "When I tie my left shoe lace first, it rains the next monday" because they think they spotted a pattern from their experience, we can test that hypothesis and find that it's WRONG.

How do we decide it is wrong? If the pattern doesn't ontologically exist, if it depends only on our minds, then what exactly makes it wrong? If there is no "right" answer in the thing being observed itself, then how can there be wrong answers?

But aside from all of that, I don't see what you present as a criticism of my position so much as offering an alternative, since This:

When we observe the Giant's Causeway, which existed before sentient observers, we discover a pattern in the relationship of the parts. — RussellA

This:

It is in the nature of sentient beings to discover patterns in what they observe, and it may well be that different sentient beings discover different patterns from the same observation. — RussellA

And This:

That you discover a duck and I discover a rabbit in the same picture does not mean that either exists in what is being observed. — RussellA

Are all also possible in my system. Nothing you've presented so far actually shows that relationships ontologically existing creates any problems. All you've done as far as I can see, is presented an alternative view that I am still not convinced makes sense. I'm unconviced because:

1- I do not see how it can account for relations that have been in effect before being found. How can a relationship be in effect if it doesn't exist yet due to no minds existing?

2- I do not see how it can account for us sometimes knowing that a relationship we discovered is wrong/not actually what's happening. How can something be wrong without there being a right answer somewhere? -

Athena

3.8kWhen we discover a pattern or a relation, we are discovering an inherent part of human nature, not something that ontologically exists in a mind-independent world. — RussellA

Athena

3.8kWhen we discover a pattern or a relation, we are discovering an inherent part of human nature, not something that ontologically exists in a mind-independent world. — RussellA

Those geometric patterns emerge through natural processes. :wink:

https://www.gizmodo.com.au/2015/11/why-is-irelands-giants-causeway-shaped-like-that/

You speak of patterns being created by our mind but this seems to miss what nature has to do with patterns. -

RussellA

2.6kThose geometric patterns emerge through natural processes — Athena

RussellA

2.6kThose geometric patterns emerge through natural processes — Athena

Yes, what we see as patterns have emerged through natural processes in nature millions of years before there was any sentient being to observe them.

I would say that we discover patterns in nature rather than create them in our minds, as it is in the nature of sentient beings to discover patterns in the world around them.

However, any discussion is complicated by the metaphorical nature of language, in that the words "emerge", "natural", "nature", "create", "processes", "discover" and "mind" are metaphorical rather than literal terms. Trying to describe literal truths in a mind-independent world using language that is inherently metaphorical is like trying to square the circle. -

RussellA

2.6kHow do we decide it is wrong? If the pattern doesn't ontologically exist, if it depends only on our minds, then what exactly makes it wrong? If there is no "right" answer in the thing being observed itself, then how can there be wrong answers? — khaled

RussellA

2.6kHow do we decide it is wrong? If the pattern doesn't ontologically exist, if it depends only on our minds, then what exactly makes it wrong? If there is no "right" answer in the thing being observed itself, then how can there be wrong answers? — khaled

A pattern cannot be right or wrong. What we infer from a pattern may be right or wrong.

If I notice the pattern that the sun has risen for the last one hundred days in the east, I may infer that tomorrow the sun will again rise in the east. My inference may be right or wrong, not the pattern that I have observed.

Nothing you've presented so far actually shows that relationships ontologically existing creates any problems — khaled

It affects your thesis that "I believe that what exists is matter, and patterns of matter" in the event that patterns of matter don't ontologically exist in a mind-independent world.

There are significant consequences in the event that patterns of matter and the relations within patterns don't ontologically exist in a mind-independent world, in that for example things that we know as "apples", "The North Pole", "mountains", "tables", "trees", etc don't exist in a mind-independent world but only exist in our minds. -

RussellA

2.6kThose geometric patterns emerge through natural processes — Athena

RussellA

2.6kThose geometric patterns emerge through natural processes — Athena

I do not see how it can account for relations that have been in effect before being found — khaled

We look at the Giant's Causeway and see patterns in the rocks and adjacent water. The question is, do these patterns, and the relationships between their parts, ontologically exist in the mind-independent world or only in the mind of the observer.

One of my problems with the ontological existence of patterns in a mind-independent world, and the relations between their parts, is where exactly do they exist.

When looking at the image, we know that A and B are part of one pattern and D and E are part of a different pattern.

But within the mind-independent world, where is the information within A that it is part of the same pattern as B but not the same pattern as D. If there is no such information, then within the mind-independent world, patterns, and the relations between their parts, cannot have an ontological existence.

One could say that patterns and relations have an abstract existence, in that they exist but outside of time and space. This leaves the problem of how do we know about something that exists outside of time and space. I could say that I believe that unicorns exist in the world but outside of time and space, but as I have no knowledge of anything outside of time and space, my belief would be completely unjustifiable.

One could say that the force experienced by A due to B is sufficient to argue that as A and B are related by a force, this is sufficient to show that A and B are part of the same pattern. However, even though A may experience a force, there is no information within the force that can determine the source of the force, whether originating from B or D. This means that there is no information within the force experienced by A that can determine one pattern from another.

Question: Sentient beings observe patterns in a mind-independent world, but for patterns to ontologically exist in a mind-independent world, there must be information within A that relates it to B but not D. Where is this information? -

khaled

3.5kOne of my problems with the ontological existence of patterns in a mind-independent world, and the relations between their parts, is where exactly do they exist. — RussellA

khaled

3.5kOne of my problems with the ontological existence of patterns in a mind-independent world, and the relations between their parts, is where exactly do they exist. — RussellA

Again, I don't think something needs to have a location to exist mind independently. Electrons do not have a set location, and they definitely exist in a mind-independent world.

One could say that patterns and relations have an abstract existence, in that they exist but outside of time and space. This leaves the problem of how do we know about something that exists outside of time and space. — RussellA

By being pattern recognizing creatures. We have the ability to notice the abstract patterns that exist (indepencently of us).

Again, you keep using the word "discover" about patterns. For something to be discoverable, it must already exist yes?

When looking at the image, we know that A and B are part of one pattern and D and E are part of a different pattern. — RussellA

That's not true? That's certainly one way to parse the patterns, but one could also look at the pattern of "Giant's causeway and its adjacent shore" and A,B,C,D,E,F are all part of that pattern.

You placed some patterns in a set, forming another pattern, then placed the rest in another set, forming yet another pattern, then were surprised when the universe did not ontologically have the split you just arbitrarily created.

If there is no such information, then within the mind-independent world, patterns, and the relations between their parts, cannot have an ontological existence. — RussellA

Let's dig down on what this actually means. If minds were to disappear tomorrow what happens to pattern D? Does Giant's Causeway stop taking the rough shape of stairs? What shape does it take instead?

In order for something to exist it must have a form, a blueprint. That's all I mean by pattern.

However, even though A may experience a force, there is no information within the force that can determine the source of the force, whether originating from B or D. This means that there is no information within the force experienced by A that can determine one pattern from another. — RussellA

This just seems like a non-sequitor.

Again, all the information you need to determine the interaction between A and B, is in the SYSTEM that includes BOTH A and B. Idk why that information not existing in the system that is just A implies that patterns don't exist...

but for patterns to ontologically exist in a mind-independent world, there must be information within A that relates it to B but not D. — RussellA

False.

We're just talking past each other. You keep saying the same stuff and I keep quoting and responding to it. Then instead fo quoting my responses and replying, you just restate what you already said. I believe this fits the pattern "endless loop"

How about I ask a question then. Could you at least address this one directly?: You keep saying patterns are discovered. How can something that doesn't ontologically exist be discovered as opposed to imagined? -

RussellA

2.6kElectrons do not have a set location, and they definitely exist in a mind-independent world. — khaled

RussellA

2.6kElectrons do not have a set location, and they definitely exist in a mind-independent world. — khaled

Electrons are not abstract entities, in that they have a mass and exist in a cloud surrounding an atomic nucleus. It is not that the position of an electron cannot be measured, rather, if you know precisely where a particle is you don't know what direction it is going.

How can something that doesn't ontologically exist be discovered as opposed to imagined? — khaled

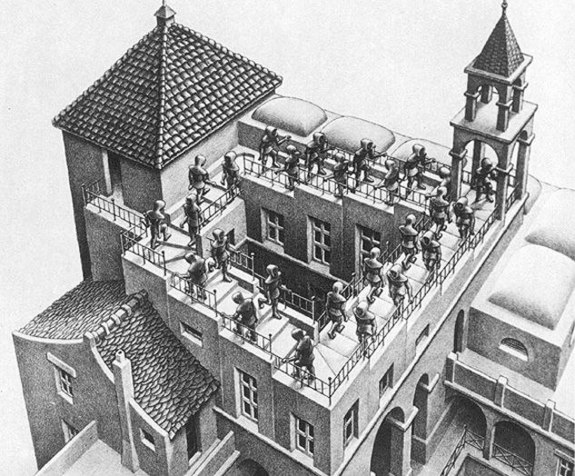

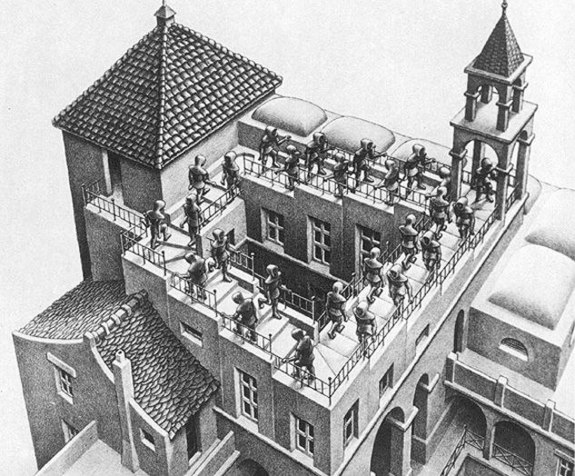

I didn't create or imagine this image, but discovered it on the internet. The ever-ascending stair doesn't exist in the world, even though that is what I observe. What I observe is an illusion, in the same way that patterns I discover in the world are illusions.

We have the ability to notice the abstract patterns that exist (indepencently of us). — khaled

I agree that patterns exist in the mind. The question is, do patterns ontologically exist in a mind-independent world.

A pattern as a whole is a regularity in the parts that make it up. I have no doubt that parts do exist in a mind-independent world, such as elementary particles and elementary forces. What I doubt is that sets of parts in a mind-independent world have an existence as a whole in addition to the individual parts.

We see a pattern in the rocks of the Giant's Causeway, even though the parts are not exactly regular. How regular does a pattern need to be for us to judge it as a pattern. If the distance between the parts varies by 1mm, the whole is definitely a pattern. If the distance between parts varies by 1cm, the whole is probably a pattern. If the distance between parts varies by 10cm, the whole may or may not be a pattern. If the distance between parts varies by 1 metre, the whole is definitely not a pattern.

As no pattern is exactly regular, whether the set of parts makes a pattern is determined by the judgement of the observer. There is nothing within the set of parts that is able to judge whether the whole that they are part of is a pattern or not. No part can judge whether it is part of a whole or not. The whole cannot judge that it is a whole made up of parts.

If patterns did ontologically exist in a mind-independent world, then as no pattern can be exactly regular, something within either the parts or the set of parts as a whole would have to have judged whether it was a pattern or not. Without recourse to the existence of a god sitting in judgement as to whether a set of irregular parts was a pattern or not, I don't see this as a possibility.

We judge whether the image is of a duck or rabbit, there is no information within the image that determines one way or the other. We judge that the pebbles make a pattern, even though they are neither regularly spaced nor sized, the pebbles cannot make that judgement. We judge when an object such as an apple is no longer an apple, the apple is no judge. We make a judgement in the Sorites Paradox when a heap of sand becomes a non-heap of sand, the sand cannot make any such judgement.

The mind judges when an irregular set of parts makes a pattern or is a non-pattern. If patterns did exist in a mind-independent world, then the problem would be in finding a mechanism within the mind-independent world that determines whether an inevitably irregular set of parts is a pattern or non-pattern. -

Athena

3.8kYes, what we see as patterns have emerged through natural processes in nature millions of years before there was any sentient being to observe them.

Athena

3.8kYes, what we see as patterns have emerged through natural processes in nature millions of years before there was any sentient being to observe them.

I would say that we discover patterns in nature rather than create them in our minds, as it is in the nature of sentient beings to discover patterns in the world around them.

However, any discussion is complicated by the metaphorical nature of language, in that the words "emerge", "natural", "nature", "create", "processes", "discover" and "mind" are metaphorical rather than literal terms. Trying to describe literal truths in a mind-independent world using language that is inherently metaphorical is like trying to square the circle. — RussellA

I love that explanation. :heart: It fits perfectly with what I was thinking. Life is constant change but our language focuses on material manifestations, things. We have lost all the animism from our understanding of life. So a form is no longer Plato's understanding of form being manifest from an external force. But animation is a cartoon we create. :chin: Sometimes poetry seems better for understanding than our Romanized language of things. If I knew I had 300 years to live, I would study Chinese so I could think of everything as that language explains life.

That is an exciting thought.One of my problems with the ontological existence of patterns in a mind-independent world, and the relations between their parts, is where exactly do they exist. — RussellA -

khaled

3.5kIf patterns did ontologically exist in a mind-independent world, then as no pattern can be exactly regular, something within either the parts or the set of parts as a whole would have to have judged whether it was a pattern or not. — RussellA

khaled

3.5kIf patterns did ontologically exist in a mind-independent world, then as no pattern can be exactly regular, something within either the parts or the set of parts as a whole would have to have judged whether it was a pattern or not. — RussellA

Or that the pattern is simply irregular. ABABABABAB is a pattern. ABABBABBAABA is also a pattern. The second being irregular. It is our judgement that it is irregular. But both patterns exist. Some collections of things are arranged per the first pattern, others are arranged per the second.

Which also addresses this:

If patterns did exist in a mind-independent world, then the problem would be in finding a mechanism within the mind-independent world that determines whether an inevitably irregular set of parts is a pattern or non-pattern. — RussellA

There is no need for determining. The pattern is whatever form the irregular set takes.

I prefer "arrangement" to "pattern"

— unenlightened

Yea that sounds better. — khaled

Electrons are not abstract entities, in that they have a mass and exist in a cloud surrounding an atomic nucleus. It is not that the position of an electron cannot be measured, rather, if you know precisely where a particle is you don't know what direction it is going. — RussellA

It's more than that. Particles act as waves sometimes. See double slit experiment. In the experiment it's not that the electron is in a specific position that if we know, we just wouln't know where it is, the electron is in no specific position at all. In that case, you have a good example of something ontologically existing without having a location. -

RussellA

2.6kOr that the pattern is simply irregular. ABABABABAB is a pattern. ABABBABBAABA is also a pattern. The second being irregular. It is our judgement that it is irregular. But both patterns exist. — khaled

RussellA

2.6kOr that the pattern is simply irregular. ABABABABAB is a pattern. ABABBABBAABA is also a pattern. The second being irregular. It is our judgement that it is irregular. But both patterns exist. — khaled

You say that "All patterns exist independently of anything", inferring that before sentient beings there were some things that existed as a pattern and some things that existed as a non-pattern.

It is true that with hindsight a sentient being can judge which was a pattern and which was a non-pattern.

But in the absence of a judgement by a sentient being, either at that time or subsequently, what determines that one thing exists as a pattern and and another thing exists as a non-pattern, particularly when patterns may be regular or irregular. -

Daniel

462

Daniel

462

But the relations between two groups of things may depend on the regularity of the patterns they (the things) form within their groups, independent of their awareness about each other patterns. The configuration of parts in a composite relative to other parts in the same composite may define how a composite interacts with another even if none of the composites or their parts is aware of such configuration. A pattern would exist independently of a sentient being if the pattern is responsible for a set of relations which would be absent in its absence. -

khaled

3.5kYou say that "All patterns exist independently of anything", inferring that before sentient beings there were some things that existed as a pattern and some things that existed as a non-pattern. — RussellA

khaled

3.5kYou say that "All patterns exist independently of anything", inferring that before sentient beings there were some things that existed as a pattern and some things that existed as a non-pattern. — RussellA

What? How did you make that inference?

No, everything that exists has a pattern/arrangement. No judgement is needed. To think a judgement is needed for a pattern to exist is to assume that patterns are mind-dependent, begging the question.

Just like every object we can see has a shape. We do not need to judge what the shape is or have a word for the shape, and yet the object has a shape. This screen will continue to be square even if we had no word for "square" and even if no one had seen this screen before. What would an object without a shape look like? What would an object without an arrangement look like (since you seem to think those don't exist)?

And the arrangement "square" that the screen has determines some of its capabilities. A square can be laid flat, whereas a sphere can't. Thus, we can see that the arrangement of the screen has real world consequences.

If on top of that, the arrangement was entirely mind dependent, then we should be able to change the capablities of the screen by arbitrarily judging it to have different arrangement, but we cannot do that. If I judge the screen to be spherical that will not suddenly allow me to roll the screen on the floor smoothly. Thus, my judgement does not seem to determine what arrangement the screen has, only what arrangement I think it has.

In short: Although the arrangement of an object affects its capabilities, even if we judge that the object posseses an arrangement X, that does not grant it the capabilites that X would grant. Thus, which arrangement the object actually possesses must not be determined by our minds. Thus arrangements are mind independent. -

RussellA

2.6kBut the relations between two groups of things may depend on the regularity of the patterns they (the things) form within their groups, independent of their awareness about each other patterns — Daniel

RussellA

2.6kBut the relations between two groups of things may depend on the regularity of the patterns they (the things) form within their groups, independent of their awareness about each other patterns — Daniel

Keeping with your terminology, accepting that trying to explain a mind-independent world using metaphorical language is inherently problematic, and using "aware" in the sense of having information.

If two things in a mind-independent world have no "awareness" about each other, then how can each thing be "aware" that it is part of a pattern that includes the other thing. -

RussellA

2.6kNo, everything that exists has a pattern/arrangement. — khaled

RussellA

2.6kNo, everything that exists has a pattern/arrangement. — khaled

You wrote "I believe that what exists is matter, and patterns of matter."

The Cambridge Dictionary defines arranges as "to put a group of objects in a particular order" and pattern as " a regular arrangement of lines, shapes, or colours"

They have in common the concept particular order or regular arrangement.

If I understand correctly, you are saying that as everything in a mind-independent world is in a particular order or regular arrangement, then there is nothing that is not in a particular order or regular arrangement.

However, no single part can be in a particular order or regular arrangement, only the whole, the set of parts.

If everything in a mind-independent world is in a particular order or regular arrangement, either each part has information that it is a part of of a particular order or regular arrangement, or the whole has information that its parts are in a particular order or regular arrangement.

How ? -

khaled

3.5kpattern as " a regular arrangement of lines, shapes, or colours" — RussellA

khaled

3.5kpattern as " a regular arrangement of lines, shapes, or colours" — RussellA

I have since then also said:

I prefer "stuff" to "matter", and I prefer "arrangement" to "pattern"

— unenlightened

Yea that sounds better. — khaled

The Cambridge Dictionary defines arrangement as "a particular way in which things are put together or placed". No mention of regularity.

If I understand correctly, you are saying that as everything in a mind-independent world is in a particular order or regular arrangement, then there is nothing that is not in a particular order or regular arrangement. — RussellA

Correct. There is nothing in the world that is not in a particular order. Don't know where you got the "regular arrangement" bit since that is not a common concept between the two definitions.

Can you give an example of something that is not in any arrangement? Or an object that has no shape?

However, no single part can be in a particular order or regular arrangement, only the whole, the set of parts. — RussellA

A set can include one object only. So this is not a problem.

If everything in a mind-independent world is in a particular order or regular arrangement, either each part has information that it is a part of of a particular order or regular arrangement, or the whole has information that its parts are in a particular order or regular arrangement. — RussellA

Too vague. What does something inanimate "having" information even mean?

But again, I don't see any responses from you. When I present an argument, you ignore it and come up with a new way to say the same thing I have argued against. There is no point in this exercise, so this will be my last reply.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- If dark matter is displaced by visible matter then is its state of displacement curved spacetime?

- Is the galaxy "missing dark matter" because it is too diffuse to displace the dark matter?

- Are de Broglie's "subquantic medium" and the superfluid dark matter the same stuff?

- Is dark energy the outflow of dark matter from a universal black hole?

- In an area of infinite time, infinite space, infinite matter & energy; are all odds 50/50?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum