-

Wayfarer

26.1kIn medieval philosophy, the rational soul referred to the aspect of the human being that was associated with the faculty of reason and with free will and was the animating principle of the body. Reason was considered the highest faculty, which set humans apart from other creatures and made them capable of achieving true knowledge. It was believed that the rational soul was immortal based on the idea that the rational soul was not bound to the material world, but rather existed in a higher realm of reality. The rational soul was thought to be capable of attaining knowledge of the divine through contemplation and philosophical inquiry, and considered the ultimate goal of human existence.

Wayfarer

26.1kIn medieval philosophy, the rational soul referred to the aspect of the human being that was associated with the faculty of reason and with free will and was the animating principle of the body. Reason was considered the highest faculty, which set humans apart from other creatures and made them capable of achieving true knowledge. It was believed that the rational soul was immortal based on the idea that the rational soul was not bound to the material world, but rather existed in a higher realm of reality. The rational soul was thought to be capable of attaining knowledge of the divine through contemplation and philosophical inquiry, and considered the ultimate goal of human existence.

Of course, that's an archaic belief system and we know now, thanks to science, that the principle behind all our faculties (including reason) is successful adaption and procreation. -

Jamal

11.6kI don’t disagree with your description of medieval thinking, but it’s significant that Horkheimer does not identify the loss of objective reason with the Enlightenment’s rejection of medieval philosophy and religion:

Jamal

11.6kI don’t disagree with your description of medieval thinking, but it’s significant that Horkheimer does not identify the loss of objective reason with the Enlightenment’s rejection of medieval philosophy and religion:

This [subjective] relegation of reason to a subordinate position is in sharp contrast to the ideas of the pioneers of bourgeois civilization, the spiritual and political representatives of the rising middle class, who were unanimous in declaring that reason plays a leading role in human behavior, perhaps even the predominant role. They defined a wise legislature as one whose laws conform to reason; national and international policies were judged according to whether they followed the lines of reason. Reason was supposed to regulate our preferences and our relations with other human beings and with nature. It was thought of as an entity, a spiritual power living in each man. This power was held to be the supreme arbiter—nay, more, the creative force behind the ideas and things to which we should devote our lives. — Horkheimer

So for Horkheimer it’s not only traditional societies that had objective reason. In the Enlightenment, reason was still supposed to help us determine the right ends and not merely the means. The change comes with industrialization.

Of course he does also say that the Enlightenment was a step towards subjective and instrumental reason. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI might agree, but materialism has no concept of telos. There is no possibility of intentionality outside the intentional actions of agents. — Wayfarer

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI might agree, but materialism has no concept of telos. There is no possibility of intentionality outside the intentional actions of agents. — Wayfarer

I think that the existence of intentionality is the pivotal issue to both philosophy and religion. Religion takes intentionality for granted, and sets up rules and conventions for the guidance of intentional acts, which become traditions. But natural philosophy, science, chews away at the underpinnings of what was taken for granted through understanding of "natural processes", and propositions of causation. This produces a shift in what is taken for granted, natural processes, rather than intentionality.

The two, natural processes and intentionality, show themselves to be incompatible because intention is based on a view toward the future, and causation is based on a view toward the past. So the two look at the activity of the passing of time at the present, in opposite directions.

The two perspectives can be characterized as free will toward future actions, and determinism from past reality. Social conventions shape which is taken for granted, such that we tend to view the other from the perspective which we take for granted, making the other a sort of illusion. The modern environment, of a society shaped by scientific development inclines us to see intentionality from the causation based perspective, such that the mainstream force, or flow of time from the past is primary. Then intention gets modeled as a looping, feedback activity, an eddy in the flow. This lends itself to the "cyclical" representation of intention.

if you want something with more scientific rigor behind it, then I vote for the conformal cyclic cosmology of Roger Penrose or > 3d superstring theory, or Mtheory with each universe being created by interacting 5D branes. These extra dimensions of the very small, that are 'wrapped around' every point in our 3d existence, are undetectable to us but are the reason why some posit nonsense such as 'something from nothing.' Quantum fluctuations are probably caused by these extra dimensions. The system is most likely (so for me, warrants a high credence level,) cyclical and eternal.

All of these similar 'cyclical and eternal' proposals are far far more likely and far far more rational that any theological posit (normally flavoured by some supernatural agency with intentionality) I have ever heard and any I am ever likely to hear about. — universeness

The "cyclical" model is probably best presented, in its most comprehensible form, by Aristotle, as the eternal circular motions of the planets. The cause of the eternal cycle is said to be an intentionality, the divine contemplation, a thinking, thinking on thinking. I have argued elsewhere that Aristotle dismisses this proposal, as untenable, though he is commonly cited as a proponent.

The important takeaway though is that such eternal cycles can only be comprehended as requiring a cause. Intention, being incorporated into the system as a looping feedback activity is the only thing available which is capable of producing such an eternal circle. This places intention as prior, in the absolute sense; prior as the cause of eternal cycles, and timeless balances like symmetry, and prior as the cause of semiotics.

It is this recognition, which hands priority to intention, as the view toward the future, rather than causal determinism, (the view toward the past), as the true guiding perspective. This inclines us toward religion. Then we come to understand that natural processes, as we apprehend them, really cannot be taken for granted, and the only thing which can really be taken for granted is the intention, the view toward the future, which when we turn around to see the past, has shaped us in our being at the present. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Religion certainly served pragmatic functions in many societies. It can serve to legitimize the state (e.g., the deification of Roman emperors), it can act as a check on absolutist states (e.g., Saint Ambrose forcing Emperor Theodosius to wear penitent's robes and undergo chastisement after the massacre at Thessalonica), it can act as a legal arbiter (e.g., Saint Augustine mentions much of his time being sucked up by arbitrating property disputes, estates, etc.), it can help solve collective action problems when pushing for reforms (e.g., the central role of churches in the US Civil Rights Movement, and earlier, the Abolitionist movement), and it can help provide public goods in low capacity states (e.g., churches were the main source of welfare programs and education for the lower classes in Europe for over a millennia).

Civil society organizations and the state can also provide these goods. What makes religion and philosophy unique is their ability to give people a narrative about the meaning and purpose of life, an explanation of their inner lives and the natural world.

This is something religion aims at, but also philosophy, and the two can be quite close in this respect. A world view based on Nietzschean overcoming requires that the world be valueless and meaningless for the human to become great by triumphing over this apparent emptiness. A world where man is essentially evil and always on the verge of extinction is required for the somber rationalists to triumph over the immanent disasters by building a just structure in the world despite the opposition of the legions of the selfish. Marxism also is able to offer a religious-like, all encompassing vision of the purpose of human life, one which also ends in salvation.

This is ultimately where I think the instinct to hold on to and defend dogmas comes from. They become like blocks in an arch, kick them out and the edifice collapses.

Right, the myth of progress is certainly itself a dogma in some respects. In many ways there is "nothing new under the sun." For what it's worth, I didn't much care for Pinker's "Better Angles of Our Nature," it seemed naive in many respects. His conception of progress is too focused on it's being directed at the individual level by "principles." The argument for progress as a sort of evolutionary, information theoretic selection process doesn't unfold the same way.

Progress itself can lead to reversals in progress. For example, current declines in battlefield deaths and the size of standing armies isn't a unique phenomena in history. You see the same sort of thing with the advent of the stirrup and the dominance of the mounted knight. Autonomous weapons systems might cause a similar shift.

For a period, technology favored small, professional armies over mass mobilization, and while this reduced deaths in warfare on the whole, it also seems to have enabled incredibly unequal societies were populations became bound to a warrior caste.

I do think Pinker makes a valid point about the "noble savage," and the "Hobbesian state of nature," being particularly well established dogmas in "The Blank Slate." I haven't read "Enlightenment Now," but the summary of the argument for why economic inequality isn't deleterious sounds like nonsense. If anything, inequality within states and between them seems likely to drive the next crisis point and makes solving other issues like global warming significantly more difficult. It's a case of focusing too much on easy to measure economic factors, whole ignoring factors that are as key to self-actualization, e.g., respect, status, etc. I'm more of a fan of Francis Fukuyama, at least his two volume opus surveying theories of state development, not so much the unfortunately more famous "End of History." -

universeness

6.3k

universeness

6.3k

That was a good and well reasoned post sir. I disagree completely with your conclusion, but your reasoning was very well constructed imo.

Your conclusion fails imo, as it requires an 'intentionality,' which itself would need to be cyclical.

Theism cannot escape the 'who/what created god/intentionality,' question.

The only path open to humans who exist 'within the notion of time,' is to suggest that the concept of 'eternal' has NO beginning in time. That is the only place for the HUMAN NOTION of 'true faith.'

My highest credence level (personal true faith notion) is that the 'mindless spark' is the eternal spark and your preference is that it is the 'mind/intentionality spark,' that is the eternal spark.

My viewpoint in this makes me an atheist and my main challenge to your 'eternal intentionality,' is to either make it's existence and continuing presence/existence known, NOW, or else, I see no rational reason for YOU to maintain your position. The continued hiddenness of this eternal intentionality, is very strong evidence indeed, that WE, as in the human race, should abandon the notion, because it continues to cause pernicious religious doctrine, and philosophising, that continues to hold our species back and leaves most of us, mired in primal fear of taking FULL ownership and responsibility for our own existence.

Most religions see this planet as expendable, ourselves as wretched, when compared to theistic BS notions of the divine, and 'glorification,' in the afterlife and not in the only life we know for sure, we actually experience. What a f****** waste!!!!! of the main resource we humans have, ........ TIME! -

Mww

5.4kIt was believed that the rational soul was immortal… — Wayfarer

Mww

5.4kIt was believed that the rational soul was immortal… — Wayfarer

I think I understand that as indicating the direct correlation between medieval philosophy and period-specific religion. Religion says there are Great Benefits Hereafter, philosophy says here’s how you’ll know it when you get there. Archaic indeed.

….we know now, thanks to science, that the principle behind all our faculties (including reason) is successful adaption and procreation. — Wayfarer

Hmmmm. The principle behind our successful adaptation and procreation is instinct, but does it follow that all our faculties, including reason, are instinctive? Wasn’t that the manifest point of the Enlightenment, to prove the human beast is naturally equipped for considerations beyond the capacities of the lesser, merely instinctive, beast?

Not picking a fight, honest. Just thinking out loud. -

Christoffer

2.5kInteresting comments. I'm not going to argue that you are wrong, but my take is that fear and our tendency towards dualistic thinking may lie behind most problems like this. People are frightened and are easily galvanized by scapegoating, quick fixes, sloganeering and appeals to tribal identity (white nationalism, etc). The notion that you are either for us or against us becomes a kind of touch stone for social discourse.

Christoffer

2.5kInteresting comments. I'm not going to argue that you are wrong, but my take is that fear and our tendency towards dualistic thinking may lie behind most problems like this. People are frightened and are easily galvanized by scapegoating, quick fixes, sloganeering and appeals to tribal identity (white nationalism, etc). The notion that you are either for us or against us becomes a kind of touch stone for social discourse.

I should think that in times of uncertainty, where fear is brewing and readily activated as a motivating energy (largely thanks to Murdoch in the West) we see people embracing glib answers which promise deliverance and perverse forms of solidarity.

I'm not sure that philosophy as such plays a key role here, but certainly ideas do. — Tom Storm

Would you agree that these glib answers and simplified polarization out of fear can arise out of the lack of philosophical approaches? Aren't they the emerging traits of ignoring such a mental tool? And wouldn't such tools be a way out of these?

What would happen if society were to structure some core tenets of philosophical scrutiny as virtues in rules of conduct between people. Just like we have things like handshakes, "hello" phrases etc. we include tenets of problem solving and approaches to difficult topics where emotions can play a negative role and put us in mental feedback loops.

For example, "when faced with contradictory information, never opt in to a specific perspective until more information and facts have been presented to achieve a logically high probability and consensus for a certain perspective". And further, "does the established highly probable perspective feature any known biases for me or the group following said perspective?". And further "Are these biases leaning towards other established and probable topics and what are those implications?"

In a way always putting our thinking into a feedback process where we question ourselves based on tenets of spotting biases, what types of biases, and in a form of Kantian universalization of the answers we arrive at.

If someone, in a social and economic class that collectively start to blame immigrants for the lack of jobs they believe is their right to have priority access to, were to be pushed to participate in these ideas, they can go through these tenets in order to question the validity of those ideas before surrendering to them. What biases has formed in this collective? What biases do I have within this group, within the larger group of the city, the nation, the world? Where can I get access to information about all perspectives of this?

Never settle based on too few perspectives, never accept without knowing the biases at play, always be aware that your perspectives and opinions are formed by influences, distance yourself from your opinions and examine them.

Of course there's a level of generalization I'm doing to all of this in these "short" writings. To invent or install tenets that functions as virtues in a society, they need to be solid and hard to dispute as their function is a foundation of thought, a foundational tool that we can have built in to our culture of approaching knowledge and information. But I think it is possible to form such a framework of tenets that can be applied in practice not only for people who are intellectuals or philosophically literate, but everyone.

In essence, imagine a society in which people are constantly aware of biases. It's part of the culture, like whenever someone utters an emotional rant, people aren't drawn into an emotional counter-attack but instead lifts the biases at play, not as an arrogant response, but through it being common practice.

I think that this would lead to complicated issues in society that tends to stir up emotions and create negative feedback loops, to be mitigated and bridge understanding between opposing parts far more than the debate-heavy nature of today's society.

The ideas are somewhat continued in Banno and Jamal's discussion

What I think is creating societal problems on a large scale is that our culture isn't formed around questioning yourself and your beliefs. There's no established common method. The concept of cognitive bias is something that people generally are unaware of. Some even have a superficial understanding of it, but to understand just how powerful bias is at blocking us from understanding something on a deeper level, the awareness of bias needs to be as common of a knowledge as how to cook dinner or brushing our teeth. Not specific to philosophers, but to all people.

We somewhat already have this in Kantian universalization. People doesn't realize it, don't know about it, but the tenets are there. If someone commits a crime, kills someone or steals something, a common response to that criminal would be "what do you think would happen if everyone did what you did?" This is Kantian ethics at play, without people knowing they apply it in that sentence.

If similar knowledge of biases and approaches to knowledge were to be implemented in society, such as it becoming a frame of mind just like with with Kantian universalization, then I think it would radically change how people tackle forming new ideas, but it also helps holding every-day problem solving within a more rationally based reasoning that mitigates emotional feedback loops. The challenge is to both formulate tenets that aren't too complex to keep in mind as well as installing them into our culture in a way that isn't forced. To show the benefits to the individual, the collective and overall society in a way that people want to follow them because they feel natural.

In my personal experience, this is how I approach daily life. I do not jump onto ideas and opinions lightly, I don't decide on anything before I have a somewhat objective reasoning surrounding it. What I've realized is that there's a calm to this approach. I can exist inside a conflicted space that can lead some to become extremely biased towards a certain perspective and enforce it with all their energy, but without ever doing so or at least be able to abandon such a position as soon as a rational counter-perspective is added to the mix. It helps me hold conflicting ideas in my head at the same time because I've mentally constructed a space in which the conflicted ideas are carefully evaluated and meditated on in a distance to me as a person. Because I'm fully aware of my biases I almost get a negative feeling when I'm straying too far from balanced reasoning. It helps me go through all the possible perspectives of a topic in order to examine it closer and it helps me listen better to other people and spot when they add a new perspective that I didn't have before, adding it to the internal process of reasoning.

It's this personal dedication to such tenets of philosophy as a mental tool that have helped me understand that there's something in this approach that has a positive function both on well-being in conflicting times, but also in having a balanced morality, better problem solving skills, and better methods of formulating new ideas. Of course, this is anecdotal evidence for its effect, but I've seen similar approaches in other people's reasoning to problems and ideas and witnessed a certain calm and ability to not get stuck in loops of emotional and biased reasoning and responses.

A form of extra sharp conceptualization of our own internal reasoning that detaches us from cognitive bias. Essentially thinking about thinking; thinking about your own thinking, thinking about other's thinking, thinking about past thinking... while thinking about a problem or an idea. This is the thought, why is this thought? How did this thought came to be? What other thoughts are there? Why did they come to be? Are these thoughts similar to other people's thoughts? Why? Are there any biases to these thoughts? Are those biases subjectively mine or collectively society's? And so on.

It is a form of epistemic responsibility, extending from just the balanced morality to ways of approaching all internal reasoning. -

frank

18.9kReligion certainly served pragmatic functions in many societies. It can serve to legitimize the state (e.g., the deification of Roman emperors), it can act as a check on absolutist states (e.g., Saint Ambrose forcing Emperor Theodosius to wear penitent's robes and undergo chastisement after the massacre at Thessalonica), it can act as a legal arbiter (e.g., Saint Augustine mentions much of his time being sucked up by arbitrating property disputes, estates, etc.), it can help solve collective action problems when pushing for reforms (e.g., the central role of churches in the US Civil Rights Movement, and earlier, the Abolitionist movement), and it can help provide public goods in low capacity states (e.g., churches were the main source of welfare programs and education for the lower classes in Europe for over a millennia).

frank

18.9kReligion certainly served pragmatic functions in many societies. It can serve to legitimize the state (e.g., the deification of Roman emperors), it can act as a check on absolutist states (e.g., Saint Ambrose forcing Emperor Theodosius to wear penitent's robes and undergo chastisement after the massacre at Thessalonica), it can act as a legal arbiter (e.g., Saint Augustine mentions much of his time being sucked up by arbitrating property disputes, estates, etc.), it can help solve collective action problems when pushing for reforms (e.g., the central role of churches in the US Civil Rights Movement, and earlier, the Abolitionist movement), and it can help provide public goods in low capacity states (e.g., churches were the main source of welfare programs and education for the lower classes in Europe for over a millennia).

Civil society organizations and the state can also provide these goods. What makes religion and philosophy unique is their ability to give people a narrative about the meaning and purpose of life, an explanation of their inner lives and the natural world.

This is something religion aims at, but also philosophy, and the two can be quite close in this respect. A world view based on Nietzschean overcoming requires that the world be valueless and meaningless for the human to become great by triumphing over this apparent emptiness. A world where man is essentially evil and always on the verge of extinction is required for the somber rationalists to triumph over the immanent disasters by building a just structure in the world despite the opposition of the legions of the selfish. Marxism also is able to offer a religious-like, all encompassing vision of the purpose of human life, one which also ends in salvation.

This is ultimately where I think the instinct to hold on to and defend dogmas comes from. They become like blocks in an arch, kick them out and the edifice collapses. — Count Timothy von Icarus

:up: :up: :up: -

Christoffer

2.5kI've mentally constructed a space in which the conflicted ideas are carefully evaluated and meditated on in a distance to me as a person. Because I'm fully aware of my biases I almost get a negative feeling when I'm straying too far from balanced reasoning. It helps me go through all the possible perspectives of a topic in order to examine it closer and it helps me listen better to other people and spot when they add a new perspective that I didn't have before, adding it to the internal process of reasoning. — Christoffer

Christoffer

2.5kI've mentally constructed a space in which the conflicted ideas are carefully evaluated and meditated on in a distance to me as a person. Because I'm fully aware of my biases I almost get a negative feeling when I'm straying too far from balanced reasoning. It helps me go through all the possible perspectives of a topic in order to examine it closer and it helps me listen better to other people and spot when they add a new perspective that I didn't have before, adding it to the internal process of reasoning. — Christoffer

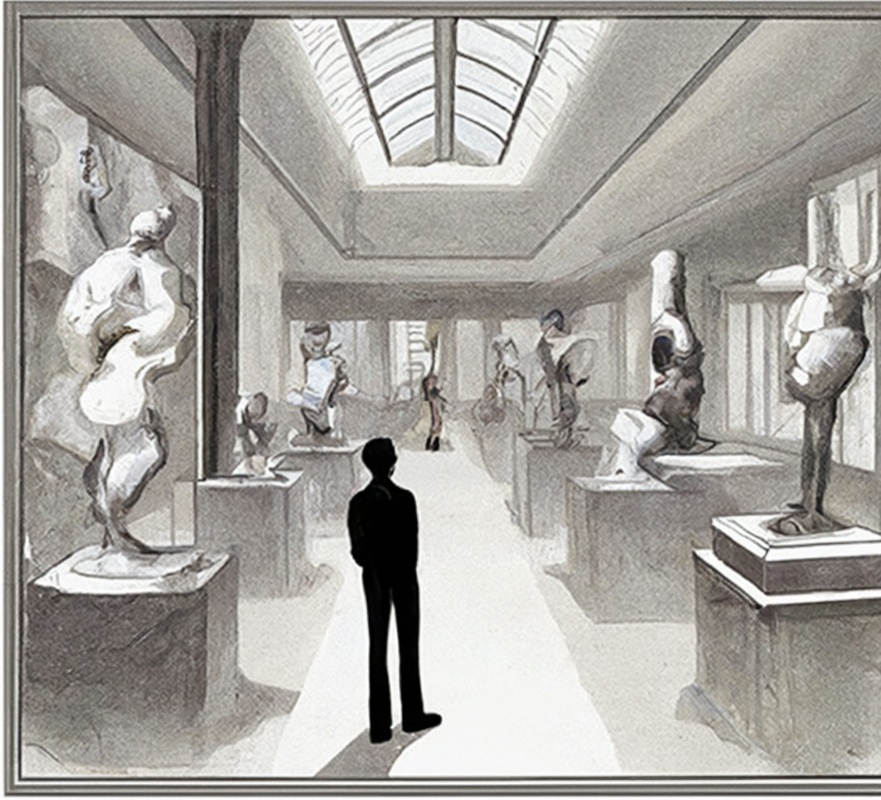

As a follow-up to this, imagine your internal reasoning being a room, a gallery, where you stand in distance from your ideas and concepts that you try to examine and evaluate.

Most people are their ideas. Their identity and their ideas and concepts are one and the same.

In essence, they are the artwork themselves, the sculpture of their ideas:

Instead, detach and construct a mental gallery with all the ideas and concept within, but be your own entity examining at a distance, without ever becoming any of the ideas and concepts yourself.

This leads to the ability to walk through the gallery of ideas and concepts in order to evaluate many different versions of the same concept or idea. Whenever someone becomes and is their idea and concept, they become a rigid stuck sculpture and can no longer walk through the gallery and consequently only be able to be examined by others. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Hmmmm. The principle behind our successful adaptation and procreation is instinct, but does it follow that all our faculties, including reason, are instinctive? Wasn’t that the manifest point of the Enlightenment, to prove the human beast is naturally equipped for considerations beyond the capacities of the lesser, merely instinctive, beast?

Yes to the latter question. This isn't just a supposition of the Enlightenment, but a core component of ancient and medieval philosophy. For Aristotle, reason was what made the human being unique. In the same way the ideal horse is strong and fleet of foot, reason is key to the essence of man; the development of reason was our telos, ultimate purpose. For Neoplatonists, logos spermatikos, universal reasons, was the principle bridging the individual soul, World-Soul, Nous, and the One, the key to the hypostasis between levels of emanation. For Hellenistic Judaism and early Christians, Logos plays a somewhat similar role to that in Neoplatonism, but without the same cosmology. Man's share in the divine Reason is what makes him "in the image/type of God."

The attack on reason seems to come from two fronts. First there is romanticism and mysticism. These traditions claim that not all experience can be properly analyzed or put into words. Ecstatic states, aesthetic appreciation, these important facets of human life are bled out by over rationalization in this view. When we speak of the divine, there are things that cannot be put into words (e.g., Pseudo Dionysus). The existentialist tradition, which is quite strong today (the only philosophy I was introduced to in high school was existentialist literature), falls into this mold to some degree. Perhaps it's not surprising then that it is arguably more popular in literature classes than philosophy ones (but most people have English and often not a single philosophy class).

I think the romantic critique gets some things right.

As to your first question, the other attack comes from scientism. In this view, our sense of reason is shaped by evolution. It is thus arguably as fallible as our other senses, which tell us that the Earth is flat, that the Sun rotates around the Earth, etc. Reason then is essentially ungrounded, emerging from the essentially meaningless universe by chance.

The problem with this latter view is that it is self-undermining. If we have no reason to believe our mathematics or reasoning is valid, then we have no reason to believe in the science that tells us this is the case and no reason to think the world should work in such a way that it is intelligible to us.

That doesn't stop the argument from being popular though. Once reason becomes ungrounded, it becomes terrifying. The ancients lived in a much less secure world, and so what they feared most was degenerating into beasts. Thus, they saw reason as divine. Today we are more scared of becoming machines, becoming slaves to an order we cannot challenge. The horrors of the Holocaust and Soviet atrocities cast a shadow over the allure of reason. It seemed to show that reason could actually make us worse.

IMO, this is a mistake. The brutality of the early 20th century, while a shock to Europe, which had seen relative peace since the Napoleonic Wars, was not at all uncommon historically. Ancient peoples didn't even attempt to hide their genocidal aims at times, making it a point of pride. Indeed, Europeans themselves were being just as brutal outside of Europe, e.g., in the Belgian Congo, during the period of continental peace. Brutality has been the norm, relative peace the deviation, and you don't see the latter without a rational organization of society.

The idea that individual reason can stop atrocities was never going to hold water. Institutions have their own logic. Individuals are the accidents of social structures, not their substance. Individuals can shape institutions, but they are moreso shaped by them. A relatively modern, educated society will have individuals commiting atrocious acts if the larger structures are not rational.

In periods of rapid economic growth, institutional development can lag development of the populace. To quote Hegel, "a[n ideal] state knows what it wills and knows it as something thought." This doesn't mean institutions have qualia, but they have their own goals that diverge from those of their members, their own intelligence, their own emergent sensory systems (think government statistics offices). The faliure of the Enlightenment was to think primarily in terms of the individual and the development of individual reason, e.g., "the legislature will be good if it has good, rational people." This leads to the naive view that political reform is just a matter of replacing bad people with good ones.

Humans have a an innate tendency to focus on agents and don't tend to think of composite entities as true agents. I think the Enlightenment view gets more right than its detractors, but it failed because it failed to take a systems perspective of the logic of societies and failed to recognize the risks of not-yet-rational institutions havening sway over society. -

Ciceronianus

3.1kIn fact, I almost used the word “anemic” in reply to Ciceronianus, the sensible no-nonsense pragmatist, but decided it was too rude. — Jamal

Ciceronianus

3.1kIn fact, I almost used the word “anemic” in reply to Ciceronianus, the sensible no-nonsense pragmatist, but decided it was too rude. — Jamal

How thoughtful and kind of you to refrain from doing so!

But what an interesting, and revealing, word to choose. "Anemic" as in lacking force, vitality or spirit. Philosophy should be forceful, vital and spirited..powerful. Examples of proper philosophy would include Bergsonian proclamations of elan vital, then; or perhaps expositions of the Will to Power, or rhapsodies regarding the ubermensch. Something more manly, maybe, like Hemingway's "grace under pressure" or masculine and spirited or spiritual, like the English philosophy of "Muscular Christianity." I could go on and on, but don't wish to seem rude.

It's true we don't encounter such clamour (or glamour) in pragmatism or analytic philosophy. But we don't see it in ancient philosophy, either. In antiquity, such thinking would have seemed merely silly. It seems to have arisen in the 19th century. And perhaps that's what philosophy is, now. It strikes me that the appeal of such thinking is emotive, sometimes even mystic, sometimes even religious. For me, the expression of such ideas is best left to artists or the religiously inclined who are certainly better at it than those who call themselves philosophers. -

Mww

5.4kThis isn't just a supposition of the Enlightenment, but a core component of ancient and medieval philosophy. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Mww

5.4kThis isn't just a supposition of the Enlightenment, but a core component of ancient and medieval philosophy. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Core component, yes, but more than a supposition for Enlightenment doctrines. If it, that is, reason itself, is already supposed, it only needs be theoretically demonstrated as the case, and if it is a logical proof should be sure to follow, sufficient to justify the theory.

I think the Enlightenment (…) failed to take a systems perspective of the logic of societies and failed to recognize the risks of not-yet-rational institutions havening sway over society. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Wouldn’t a systems perspective of societies fall under the purview of anthropology? I’m not sure how much a discipline anthropology was in the 16, 17, 1800’s, there still being minor kings, clan chieftains and whatnot doing the job of a soft science. Maybe the Enlightenment failed as you say, but I rather think the liberation of the individual mind, as you also mentioned, wouldn’t be a failure.

What is a not-yet-rational institution? -

Tom Storm

10.8kWould you agree that these glib answers and simplified polarization out of fear can arise out of the lack of philosophical approaches? Aren't they the emerging traits of ignoring such a mental tool? And wouldn't such tools be a way out of these? — Christoffer

Tom Storm

10.8kWould you agree that these glib answers and simplified polarization out of fear can arise out of the lack of philosophical approaches? Aren't they the emerging traits of ignoring such a mental tool? And wouldn't such tools be a way out of these? — Christoffer

Maybe, but I think it's unclear. I wouldn't say these answers are glib, so much as deep and instinctive. I have no idea what, if any solutions might work, but I have a strong intuition that you are unlikely to get very far trying to use reason to talk people out of a position they didn't arrive at through reason.

In my personal experience, this is how I approach daily life. I do not jump onto ideas and opinions lightly, I don't decide on anything before I have a somewhat objective reasoning surrounding it. — Christoffer

You advocate your particular approach of reasoning because this is a fundamental value through which you already view life. Good for you and good luck trying to get others to agree. But are you essentially saying here: 'If everyone thought they way I do, the world would be better?' Don't most people think that, even the prodigiously irrational ones?

Trying to reeducate society along appropriate philosophical principles sounds totalitarian (I know that's not how you intended it) and is not going to happen, it's entering a speculative realm where I have little to contribute. :wink: -

Ciceronianus

3.1k↪Ciceronianus That’s the spirit! — Jamal

Ciceronianus

3.1k↪Ciceronianus That’s the spirit! — Jamal

Now that would be an "anemic" response, as in lacking substance. (Merriam Webster Online) -

Jamal

11.6kNow that would be an "anemic" response, as in lacking substance — Ciceronianus

Jamal

11.6kNow that would be an "anemic" response, as in lacking substance — Ciceronianus

Fair.

But don’t take it personally and don’t get me wrong. I’m not recommending the Will to Power, elan vital, macho glamorous clamour, or anything like that, and I think my posts show that I don’t do that kind of philosophy and that I’m not a fascist. I just felt that philosophy defined so generally or neutrally, and without the critical aspect (in the sense of social critique), was somewhat anemic. -

Janus

17.9kThat's possibly a clue to his motivation: he sees "wokeism" as a civil religion, and since he questions it, he's questioning religion and is therefore a great philosopher. — Jamal

Janus

17.9kThat's possibly a clue to his motivation: he sees "wokeism" as a civil religion, and since he questions it, he's questioning religion and is therefore a great philosopher. — Jamal

Haha, so only the "great philosophers" question religion (read "all collective social phenomena"?)? Or do the ordinary philosophers also question, but their questions are not great?

I will say that if it's true that philosophers cannot start from a neutral transcendent foundation, that their thinking is conditioned by their time, then it might help to be aware of it. — Jamal

That sounds right...question everything, including oneself and the presuppositions that live beneath the questions; from whence do they come?

Kant, for instance, though self-consciously critical and non-dogmatic, in some ways did not take his attack on metaphysics far enough, and ended up with his own elaborate system, dogmatically rationalist in its own way (not to mention quintessentially Enlightenment and bourgeois). — Jamal

I don't know about this; Kant's categories at least seem to ring true and space and time as the pure forms of intuition too. Are they no longer viable? Aristotle's categories? Goethe said “He who cannot draw on three thousand years is living from hand to mouth.” "The poverty of historicism" says Popper.

Modernity seems to me to predominately reflect a kind of narcissism. Can we see our own reflections in the cesspool?

I doubt that Hegel's notion of thinking one's time entails a view of historical moments as monolithic and pure, since the whole point of his philosophy is to see things in their dynamic, historical, conflictual context, rather than as fixed — Jamal

Right, though in saying "monolithic" I wasn't thinking of the dichotomy between fixed and dynamic, I was thinking more of the 'monistic/ pluralistic' dichotomy: meaning that I don't think historical moments have just one "zeitgeist" but are rather boiling cauldrons in which many geists grapple with one another for supremacy. From where I stand "the state" looks like a kind of monstrous fiction. -

Wayfarer

26.1kSo for Horkheimer it’s not only traditional societies that had objective reason. In the Enlightenment, reason was still supposed to help us determine the right ends and not merely the means. The change comes with industrialization. — Jamal

Wayfarer

26.1kSo for Horkheimer it’s not only traditional societies that had objective reason. In the Enlightenment, reason was still supposed to help us determine the right ends and not merely the means. The change comes with industrialization. — Jamal

I think the change came with the Renaissance conception of humanity. Many of the Renaissance humanists held philosophical views of dubious orthodoxy, but they held the world wisdom traditions in high esteem, so they still recognised a transcendent source of values, a summum bonum. That is what was to change. Reason is still valued today, but whenever it is praised, you can bet your boots that the it is 'reason validated by empirical observation'. The focus shifted, whereby the attributes that had been assigned to the Divine are now accorded to nature herself, as there is nothing 'above' or 'higher' than nature; nature 'creates herself' (understanding of which is the holy grail of naturalism. I've noticed a book recently on the debate between the humanist Erasmus and the fundamentalist Luther, Fatal Discord, which he says lays the groundwork for many of these attributes of today's worldview).

Not picking a fight, honest. — Mww

I was hoping to start one. ;-)

Reason was supposed to regulate our preferences and our relations with other human beings and with nature. It was thought of as an entity, a spiritual power living in each man. This power was held to be the supreme arbiter — Horkheimer

For Aristotle, reason was what made the human being unique. In the same way the ideal horse is strong and fleet of foot, reason is key to the essence of man; the development of reason was our telos, ultimate purpose. — Count Timothy von Icarus

'In the Aristotelian scheme, nous was the faculty that enables human beings to think rationally. For Aristotle (and also for Aquinas and scholastic philosophy), this was distinct from the processing of sensory perception, including imagination and memory, which other animals possess. For him then, discussion of nous is connected to discussion of how the human mind sets definitions in a consistent and communicable way - which is the basis of Aristotelian realism - and whether people must be born with some innate potential to understand the same universal categories in the same logical ways. (And these universal categories were adapted by Kant.) Derived from this it was also believed in classical and medieval philosophy, that the individual must require help of a spiritual and divine type (see SEP, Divine Illumination). By this type of account, it also came to be argued that the human understanding (nous) somehow stems from this cosmic nous, which is however not just a recipient of order, but a creator of it.'

This deeply resonates with me. I can't help but see the concluding phrase reflected in Wheeler's 'participatory cosmos'.

//I also can't help but believe that a great deal of so-called empiricist and naturalist philosophy is basically irrational in nature, as it has abnegated the idea of a transcendent reason, in favour of the merely instrumental.//

Theism cannot escape the 'who/what created god/intentionality,' question. — universeness

That's because, and pardon me for saying, your conception of God is anthropomorphic, based mainly on your stereotyped depiction of (and rejection of) religion. That's not something particular to yourself, by the way. -

Banno

30.6kYour posts here have been thought provoking.

Banno

30.6kYour posts here have been thought provoking.

This last takes me back to some work I did on organisational decision making many years back; work that applies as well to individuals as to organisation. You use the metaphor of someone perusing a gallery at leisure, making calm, considered decisions. Trouble is, this is rarely what happens. Nor is is even ideally what happens. Organisations and individuals are embedded in a world in flux, were circumstances change spasmodically as often as smoothly, but also where the decision made changes the way things are.

One is tempted by the analogue with a strange attractor, after , but even a strange attractor is rhythmic and predictable compared to the path of even a simple institution, or with the unpredictable events of a lifetime.

Take any pivotal life decision, be it moving to a distant city or committing to a partner or accepting a job offer. Everything changes, unpredictably, as a result of the decision. Because of this, while there may be a pretence of rationality, ultimately the decision is irrational. Not in the sense of going against reason, but in the sense of not being rationally justified. It is perhaps an act of hope, or desperation, or sometimes just whim.

And this not only applies to big choices, but to myriad small choices. Whether you have the cheese or the ham sandwich had best not be the subject of prolonged ratiocination.

Most of our choices are not rationally determined; and this is usually a good thing, lest we all become Hamlet.

Then there are heuristics. is somewhat dismissive of cutlery, but it does make eating easier, not to mention smoothing the social aspects of the table. It's usually not possible to see the bigger picture, to understand the furthest consequences of one's choices, and even when one does, as perhaps was the case with the beginning of the arms race, the problem can be intractable, or at the least appear so. Sometimes the best one can hope for is to be able to sort stuff out in the long run. So we rely on heuristics.

pointed to the tension between wanting ethics to be taught while being suspicious of the impact of self reflection. Part of the trouble is, despite the pretence, we can not, do not, and ought not make all our decisions only after due ratiocination. -

Wayfarer

26.1kCouldn’t have chosen a better battleground than the suggestion that reason has been, or is being, eclipsed. In what world is that not a singularly foolish notion? — Mww

Wayfarer

26.1kCouldn’t have chosen a better battleground than the suggestion that reason has been, or is being, eclipsed. In what world is that not a singularly foolish notion? — Mww

It is writ large in today's world.

In his seminal 1973 paper, “Mathematical Truth,” Paul Benacerraf presented a problem facing all accounts of mathematical truth and knowledge. Standard readings of mathematical claims entail the existence of mathematical objects. But, our best epistemic theories seem to deny that knowledge of mathematical objects is possible.

What are 'our best' theories, and why do they entail that such knowledge is not possible?

Mathematical objects are in many ways unlike ordinary physical objects such as trees and cars. We learn about ordinary objects, at least in part, by using our senses. It is not obvious that we learn about mathematical objects this way. Indeed, it is difficult to see how we could use our senses to learn about mathematical objects. We do not see integers, or hold sets. Even geometric figures are not the kinds of things that we can sense. .... Mathematical objects are not the kinds of things that we can see or touch, or smell, taste or hear. If we can not learn about mathematical objects by using our senses, a serious worry arises about how we can justify our mathematical beliefs.

But those mavericks known as 'rationalists' have the temerity to claim that we actually have rational insight!

[Rationalists] claim that we have a special, non-sensory capacity for understanding mathematical truths, a rational insight arising from pure thought. But, the rationalist’s claims appear incompatible with an understanding of human beings as physical creatures whose capacities for learning are exhausted by our physical bodies.

Source. Bolds added. I've put that up as a microcosm of the larger issue, which is the fundamental irrationality of naturalism.

Some further reflections on same:

We may be sorrrounded by objects, but even while cognizing them, reason is the origin of something that is neither reducible to nor derives from them in any sense. In other words, reason generates a cognition, and a cognition regarding nature is above nature. In a cognition, reason transcends nature in one of two ways: by rising above our natural cognition and making, for example, universal and necessarily claims in theoretical and practical matters not determined b nature, or by assuming an impersonal objective perspective that remains irreducible to the individual 'I' — Alfredo Ferrarin, The Powers of Pure Reason: Kant and the Idea of Cosmic Philosophy

As a philosophical conception, Empiricism means a theory according to which there is no distinction of nature, but only of degree, between the senses and the intellect. As a result, human knowledge is simply sense-knowledge (or animal knowledge) more evolved and elaborated than in other mammals. And not only is human knowledge entirely encompassed in, and limited to, sense-experience ...; but to produce its achievements in the sphere of sense-experience human knowledge uses no other specific forces and means than the forces and means which are at play in sense-knowledge.

Now if it is true that reason differs specifically from senses, the paradox with which we are confronted is that Empiricism, in actual fact, uses reason while denying the power of reason, on the basis of a theory that reduces reason's knowledge and life, which are characteristic of man, to sense knowledge and life, which are characteristic of animals.

Hence, first, an inevitable confusion and inconsistency between what an Empiricist does -- he thinks as a man, he uses reason, a power superior in nature to senses -- and what he says -- he denies this very specificity of reason.

And second, an inevitable confusion and inconsistency even in what he says: for what the Empiricist speaks of and describes as sense-knowledge is not exactly sense-knowledge, but sense-knowledge plus unconsciously introduced intellective ingredients - sense-knowledge in which he has made room for reason without recognizing it. A confusion which comes about all the more easily as, on the one hand, the senses are, in actual fact, more or less permeated with reason in man, and, on the other, the merely sensory psychology of animals, especially of the higher vertebrates, goes very far in its own realm and imitates intellectual knowledge to a considerable extent. — Jacques Maritain, The Cultural Impact of Empiricism -

Tom Storm

10.8kThat's a nice summary. I reflect on matters like what products to buy, or where to go on a holiday. I don't really reflect greatly on life decisions - as these come intuitively and emerge from my 'whole self' - not just the rational domain in my process. Decision making is a multifactorial equation. And I also have a personality that likes to wing things.

Tom Storm

10.8kThat's a nice summary. I reflect on matters like what products to buy, or where to go on a holiday. I don't really reflect greatly on life decisions - as these come intuitively and emerge from my 'whole self' - not just the rational domain in my process. Decision making is a multifactorial equation. And I also have a personality that likes to wing things. -

Banno

30.6kThere's studies as show that those who examine Choice magazine reviews in detail tend to be less satisfied with their purchases.

Banno

30.6kThere's studies as show that those who examine Choice magazine reviews in detail tend to be less satisfied with their purchases. -

Mww

5.4kIn what world is that not a singularly foolish notion?

Mww

5.4kIn what world is that not a singularly foolish notion?

— Mww

It is writ large in today's world. — Wayfarer

Sadly yes. But not so much in the Cool Kids sandbox, ammiright?

————

….But, our best epistemic theories seem to deny that knowledge of mathematical objects is possible…”

What are 'our best' theories, and why do they entail that such knowledge is possible? — Wayfarer

Edit?

————

Given the innate human capacity for intuiting quantity, and the innate human capacity, not only for the use of conceptions but also the a priori construction of them, in relations….why do we need an indispensability argument with respect to mathematical objects?

There’s no need for a science to inform us that the intersection of two lines immediately facilitates the conception of a relation between them, which is then represented as “angle”, and there’s no need for a mere belief in the validity of the conception “angle” as a mathematical object, when such object is necessarily given as a principle hence contradictory to deny.

————-

Worthy reflections, as is usually the case. Benacerraf notwithstanding. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kYour conclusion fails imo, as it requires an 'intentionality,' which itself would need to be cyclical. — universeness

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kYour conclusion fails imo, as it requires an 'intentionality,' which itself would need to be cyclical. — universeness

Intentionality isn't cyclical. That's the problem with the materialist/physicalist representation of it, it ends up being cyclical, when in reality there is nothing to indicate that it ought to be. Since the materialist representation shows time as flowing from past to future, instead of from future to past, the only way that it can accommodate intentionality which relies on a future to past flow of time for conception, is to allow for that looping aspect. This creates the cyclical representation of intention. In reality, time only flows one way, into the past. The future (May 13 for example) will become past as time flows into the past. So the materialist representation of time, which shows the past as prior to the future, and therefore things in the past as causing what will come to be in the future, is fundamentally wrong. And the only way that they can allow for the real flow of time to have an influence on the way that they understand and represent time, is through these loops, which inevitably become externalities, and infinite cycles.

The only path open to humans who exist 'within the notion of time,' is to suggest that the concept of 'eternal' has NO beginning in time. — universeness

The conventional Christian conception of "eternal" is "outside of time". Time is measured as it passes, so only past time is capable of having been measured (measurable), and the future is therefore outside of time. All real time, as measurable time, is in the past. But the true cause of what will be at the present, must be prior to the present, therefore in the future, so this cause must also be outside of time.

There is another way to apprehend this. Imagine that there is a beginning to time. At the moment when time began there was necessarily no past time, yet there was necessarily future. And for time to begin, there must be a cause. Therefore, this cause was necessarily in the future. For time to continue passing there must always be a cause, and this cause is always in the future.

My viewpoint in this makes me an atheist and my main challenge to your 'eternal intentionality,' is to either make it's existence and continuing presence/existence known, NOW, or else, I see no rational reason for YOU to maintain your position — universeness

So, that is the rational, explained above. As time passes, there must be cause of things being as they are, at each moment of passing time. Since time flows from the future to the past, the cause of things being as they are at the present must always be in the future in relation to what comes to be at the present. This is the cause which is always outside of time (eternal), as prior to time.

We experience this cause which is outside of time as intentionality. Whenever we want things to be in a specific way at a specific moment as time passes, we make an intentional act, and this causes the situation to come to be as we desired. The act of the will is prior to what comes to be from it. So intention is how we as human beings, partake in this eternal cause which is always prior to time.

The continued hiddenness of this eternal intentionality... — universeness

That the future is always hidden from us, and no part of it can ever be sensed by any of our senses, in no way indicates that it is not real. It is logically necessary to conclude that the future must be in some way real, or else time could not be passing. As explained above, the cause of time passing is always in the future in relation to the present.

mired in primal fear of taking FULL ownership and responsibility for our own existence — universeness

The idea that we ought to take full ownership and responsibility for our own existence is utterly ridiculous. Do you not allow that your parents are somewhat responsible for your existence, and that your schoolers are somewhat responsible for your ideology? -

Jamal

11.6kI don't know about this; Kant's categories at least seem to ring true and space and time as the pure forms of intuition too. Are they no longer viable? Aristotle's categories? Goethe said “He who cannot draw on three thousand years is living from hand to mouth.” "The poverty of historicism" says Popper. — Janus

Jamal

11.6kI don't know about this; Kant's categories at least seem to ring true and space and time as the pure forms of intuition too. Are they no longer viable? Aristotle's categories? Goethe said “He who cannot draw on three thousand years is living from hand to mouth.” "The poverty of historicism" says Popper. — Janus

I just wrote an elaborate refutation of the transcendental deduction of the categories, but the dog ate it. So I'll just say that I don't think I'm an unqualified historicist; as I say, I'm confused about the issue. I think Kant and Aristotle were great, but I also think their philosophies suffer from a lack of historical and social awareness (although it occurs to me that it's precisely because they ignored all that that they achieved what they did, rather than despite it).

It's more difficult to see in their theoretical philosophy than in their ethics and politics: Aristotle defended slavery philosophically without considering that his defence was a result of his class and his society, and Kant's emphasis on autonomous reason in retrospect clearly reflects his Enlightenment bourgeois milieu.

Right, though in saying "monolithic" I wasn't thinking of the dichotomy between fixed and dynamic, I was thinking more of the 'monistic/ pluralistic' dichotomy: meaning that I don't think historical moments have just one "zeitgeist" but are rather boiling cauldrons in which many geists grapple with one another for supremacy. From where I stand "the state" looks like a kind of monstrous fiction. — Janus

I see what you mean. Interesting point. I don't know what Hegel would say to that. -

universeness

6.3kThat's because, and pardon me for saying, your conception of God is anthropomorphic, based mainly on your stereotyped depiction of (and rejection of) religion. That's not something particular to yourself, by the way. — Wayfarer

universeness

6.3kThat's because, and pardon me for saying, your conception of God is anthropomorphic, based mainly on your stereotyped depiction of (and rejection of) religion. That's not something particular to yourself, by the way. — Wayfarer

Consider the requested pardon, granted. Your are wrong, as I am willing to envisage a god image as it is presented to me by a proposer, anthropomorphic, animist, disembodied esoteric/ethereal, pantheistic, etc it's all the same woo woo BS to me. There are many followers of religion who behave stereotypical, there are also theist sympathisers who type stereotypical responses to criticism of theism. I would include you in that categorisation. I don't see any particular value in this side alley you are attempting as a response to my point, it is not a useful or even credible answer to it, at all.

Theism cannot escape the 'who/what created god/intentionality,' question.

— universeness — Wayfarer -

Wayfarer

26.1kas I am willing to envisage a god image…it's all the same woo woo BS to me….I don't see any particular value in this side alley — universeness

Wayfarer

26.1kas I am willing to envisage a god image…it's all the same woo woo BS to me….I don't see any particular value in this side alley — universeness

Apologies, I mistook you for someone who might have an open mind. I’ll keep out of your way in future. -

universeness

6.3kIntentionality isn't cyclical. That's the problem with the materialist/physicalist representation of it, it ends up being cyclical, when in reality there is nothing to indicate that it ought to be. Since the materialist representation shows time as flowing from past to future, instead of from future to past, the only way that it can accommodate intentionality which relies on a future to past flow of time for conception, is to allow for that looping aspect. This creates the cyclical representation of intention. In reality, time only flows one way, into the past. The future (May 13 for example) will become past as time flows into the past. So the materialist representation of time, which shows the past as prior to the future, and therefore things in the past as causing what will come to be in the future, is fundamentally wrong. And the only way that they can allow for the real flow of time to have an influence on the way that they understand and represent time, is through these loops, which inevitably become externalities, and infinite cycles. — Metaphysician Undercover

universeness

6.3kIntentionality isn't cyclical. That's the problem with the materialist/physicalist representation of it, it ends up being cyclical, when in reality there is nothing to indicate that it ought to be. Since the materialist representation shows time as flowing from past to future, instead of from future to past, the only way that it can accommodate intentionality which relies on a future to past flow of time for conception, is to allow for that looping aspect. This creates the cyclical representation of intention. In reality, time only flows one way, into the past. The future (May 13 for example) will become past as time flows into the past. So the materialist representation of time, which shows the past as prior to the future, and therefore things in the past as causing what will come to be in the future, is fundamentally wrong. And the only way that they can allow for the real flow of time to have an influence on the way that they understand and represent time, is through these loops, which inevitably become externalities, and infinite cycles. — Metaphysician Undercover

Your own words 'will become' in the context you use them, contradicts your 'time flows into the past' claim, 'will become' has not happened yet. The expansion of the universe allows for 'future' to exist as more 'distance' is created, which creates more 'time' or 'spacetime'. So the flow into the future is constant but can be experienced at different relative speeds, depending on observer reference frame (time dilation).

Entropy will convert all available energy into spacetime eventually. This is akin to CCC, as at some point the size of the expansion is all that will remain and AT that point, size becomes meaningless and the universe becomes again, the same state as a singularity and a new Aeon begins. NO intentionality required.

For humans, time is an 'individual experience' as is past, present and future. I think Carlo Rovelli, describes this best, currently.

Which is why it fails, as such a notion is meaningless and irrational.The conventional Christian conception of "eternal" is "outside of time". — Metaphysician Undercover

What do you mean by 'real time' in the context you employ it?All real time, as measurable time, is in the past. But the true cause of what will be at the present, must be prior to the present, therefore in the future, so this cause must also be outside of time. — Metaphysician Undercover

All measured time is relative, are you referring to proper time, as described here?

This sentence makes no sense.But the true cause of what will be at the present, must be prior to the present, therefore in the future, so this cause must also be outside of time. — Metaphysician Undercover

Thank goodness for that!There is another way to apprehend this. — Metaphysician Undercover

Ok!Imagine that there is a beginning to time. — Metaphysician Undercover

Not necessarily true, there may have been a previous Aeon. So the moment you describe here is a recalibration of a notion of a 'universal time,' reference frame.At the moment when time began there was necessarily no past time, — Metaphysician Undercover

I don't see any use for the word 'necessarily' here but yes, the notion of future becomes valid at this point, due to spacetime inflation/expansion, NO intentionality required.yet there was necessarily future. — Metaphysician Undercover

Yes, the end of the previous cycle, NO intentionality required.And for time to begin, there must be a cause. — Metaphysician Undercover

Why?Therefore, this cause was necessarily in the future. — Metaphysician Undercover

No, the cause is the expansion of spacetime and it happens during every time unit/duration.For time to continue passing there must always be a cause, and this cause is always in the future. — Metaphysician Undercover

The rest of what you typed is just based on your bizarre ideas, regarding how time works.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum