-

plaque flag

2.7k

plaque flag

2.7k

Another related issue that occurs to me is the shift from the low-tech plausibility of an essentially cyclic world to a sense that the world was developing, gathering complexity, and in some sense moving toward an apotheosis or an apocalypse. A cyclic world is a disguised stasis. A sage at peace with its eternal nature makes sense. But the second world tempts the revolutionary to find a seat on the right side of the progress god History. -

Fooloso4

6.2k

Fooloso4

6.2k -

plaque flag

2.7kI am in general agreement, but would not characterize the statis as "disguised". — Fooloso4

plaque flag

2.7kI am in general agreement, but would not characterize the statis as "disguised". — Fooloso4

Just to be clear, I imagine a world in which cities alternate between tyrants and democracies, almost randomly. So there's change/motion, but the timebinding philosopher can come to grasp the field or governing matrix of possibly as constantly present and static. Perhaps you already understood me to mean this. I got it from Kojeve discussing Aristotle. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Absolutely. To be honest, I think even the "death of [just] metaphysics," has been greatly exaggerated. Plenty of philosophy tops the best sellers list, e.g., Eckhart Tolle; it is just less likely to be written by professional philosophers these days, as the discipline has become quite specialized and philosophers often don't write in ways that will make their works widely appealing. Plenty of popular theology also has a fair amount of philosophy blended into it, commentaries on the Bible, the Patristics, etc. This shift isn't necessarily a bad thing, the role of the professional philosopher changed for a reason, although it is perhaps a sad thing, as I think that could be gained by philosophy having more widespread appeal.

I recently wrote an article on this: https://medium.com/p/1992ecb87d9

Has science taken over completely from philosophy?

To be sure, even those who would agree with Hawking would allow that philosophy remains relevant for certain necessarily subjective areas of inquiry: ethics, aesthetics, perhaps even the philosophy of language. But what about the questions:

How do we know what we know?

What actually exists?

What is fundamental?

What is subjective experience?

To my mind, these seem like inherently philosophical questions. They are questions whose answers must be informed by the natural sciences, but not the sort of questions that can be answered by the empirical sciences.

Yet it is also clear that scientists often do tend to try to answer these questions. Indeed, in the world of popular science books, I would argue that perhaps most of what is addressed are questions of philosophy— i.e., questions that are not empirically falsifiable or verifiable, questions whose answers make metaphysical claims.

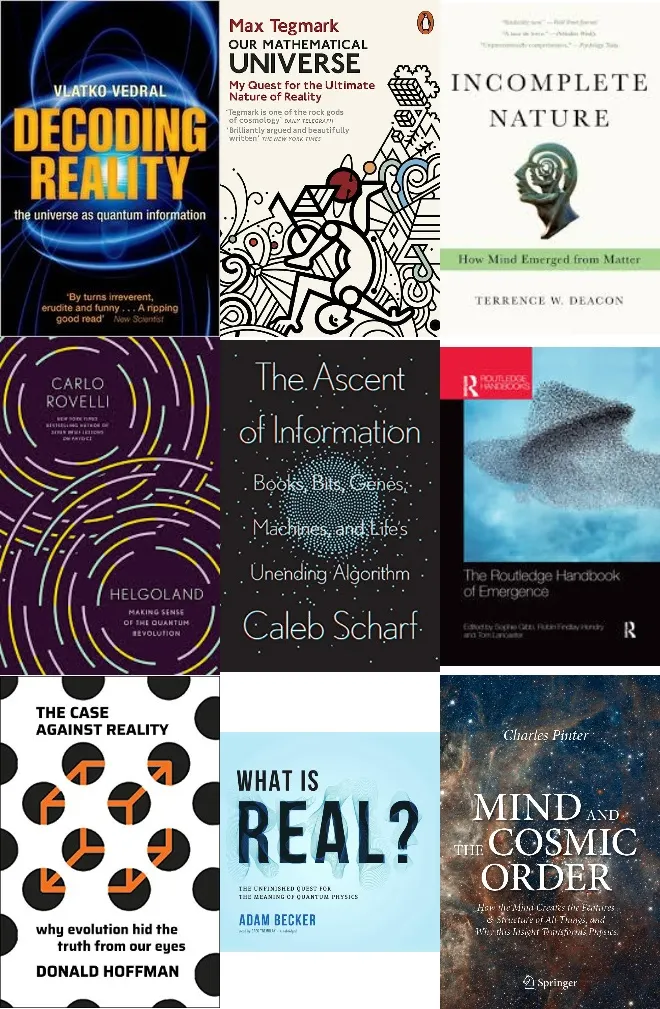

The books above are either written by practicing scientists or journalists who specialize in the natural sciences. However, they are filled to the brim with hypothesis about metaphysics.

For just one example, take the popular claim in many works of popular physics: “eternalism is true.” That is, “all times, past, present, and future, exist, and exist in the same sense.” It is not clear if it is even possible to test such a hypothesis empirically. Indeed, I would argue that evidence from physics itself actually cautions against such a view. But in any event, in every case I can recall, the case for eternalism has relied heavily on philosophical arguments and analogies to mathematics (I may do an article on this issue in the future).

Metaphysics: Not So Dead After All?

Metaphysics is alive and well. Every big-name physicist appears to be advancing their own metaphysics these days.

- Carlo Rovelli has set forth a relational ontology of interaction that is similar to that advocated by second century Buddhist philosopher Lu-Trub Nāgārjuna.

- Max Tegmark has his Mathematical Universe Hypothesis, the idea that the universe is an abstract, mathematical object — a sort of ontic structural realism cum mathematical Platonism.

- John Wheeler and the many scientists he has inspired have advanced a new sort of immaterialism in the form of “It From Bit,” — the hypothesis that the universe is fundamentally composed of information.

- David Deutsch, Seth Lloyd , Vlatko Vedral, Paul Davies, etc. take this “informational” view in new directions, but all have advanced conceptions of a “computational universe.”

- Donald Hoffman, a cognitive scientist, advances his Cognitive Realism, an idealist ontology, based on an empirical argument.

- Complexity studies is often built around metaphysical claims about emergence.

- Information theory and complexity studies both tend to make claims about the ontological existence of incorporeal entities across a number of fields, e.g. that things like economic recession, turbulence, etc. actually exist and are not reducible to fundamental particles.

- The move to explain things in terms of processes instead of substances is a metaphysical move. E.g., the move from understanding fire in terms of phlogiston (a substance) to understanding fire in terms of combustion (a process); heat as the substance caloric, to heat existing in terms of random kinetic motion; life in terms of vital substance to life being understood in terms of certain kinds of far from thermodynamic equilibrium processes.

- Quantum field theory tells us the “fundamental” part(icle) can only be explained in terms of the whole, which is a mariological claim.

- Claims about computation being analogous to causality are also metaphysics.

- Black Hole Cosmology or multiverse theories (Everett’s Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics or those stemming from Eternal Cosmic Inflation) necessarily have to make metaphysical claims about what exists. Eternalism, or opposed claims of local becoming, the block universe model, the advancing block universe, the crystallizing block universe, are all, to some degree metaphysical theories. String theory works on a set of ontological claims.

That these ontological claims can be vetted using empirical evidence does not make them uniquely different from past metaphysics. As Rovelli points out, Aristotle’s physics held up for so long precisely because it jives with empirical observations. That is, Galileo’s findings were not intuitive, it requires very precise experimental conditions to confirm that a feather and a cannon ball will fall at the same rate in a vacuum. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Thanks. It's nice to get a report from the field.

Interesting that you highlight the idea of introducing a bit more organization or discipline into people's thoughts and discussions. Obviously value in that, and it's value people associate with philosophy, so that's something. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kThe modern philosophers gave themselves a task not entertained by the ancients, to master nature. Philosophy was no longer about the problem of how to live but to solve problems by changing the conditions of life. — Fooloso4

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kThe modern philosophers gave themselves a task not entertained by the ancients, to master nature. Philosophy was no longer about the problem of how to live but to solve problems by changing the conditions of life. — Fooloso4

Perhaps true, but it's not like no one built houses or roads or engaged in agriculture until Bacon. Man had been changing the conditions of life for millennia by the 16th century. -

Fooloso4

6.2k

Fooloso4

6.2k

Certainly there had been scientific and technological advances, but nothing on the scope of the scientific revolution. -

Wayfarer

26.1kSplendid post and very much on point. (You also just got a new follower on Medium ;-) )

Wayfarer

26.1kSplendid post and very much on point. (You also just got a new follower on Medium ;-) )

Another book that would qualify for your list is The One: How an Ancient Idea Holds the Future of Physics, Heinrich Pas - a novel presentation of philosophical monism.

There's an enormous thirst for penetrating metaphysical and philosophical analysis. Quite apart from the fact that all of us here spend some time each day discussing it on this very forum, there's a huge and ever-growing list of web portals and organisations about ideas: aeon.co, scienceandnonduality.com, bigthink.com, closertotruth.com, and iai.tv come to mind, without even having to think about it. The latter hosts numerous livestreamed panel conversations with philosophers, scientists and technologists. Youtube has millions of streamed sessions and presentations on metaphysical topics. As John Haldane put it in response to Stephen Hawking's put-down of philosophy as not being able to keep up with physics, philosophy lives! -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe modern philosophers gave themselves a task not entertained by the ancients, to master nature. — Fooloso4

Wayfarer

26.1kThe modern philosophers gave themselves a task not entertained by the ancients, to master nature. — Fooloso4

Is that the task of the philosopher, or of the engineer, technologist and scientist? I would have thought the philosophers would have plenty on their hands figuring out a meaningful narrative in the midst of constant upheavel.

Certainly there had been scientific and technological advances, but nothing on the scope of the scientific revolution. — Fooloso4

I really don't know how you can say that. Our entire worldview is going through revolutionary changes with incredible speed. The world is literally changing before our eyes. -

Janus

17.9kI was thinking more along the lines of pre-critical ancient schools of philosophy with their (unquestioned) doctrines and spiritual exercises as described by Pierre Hadot. It would be closer to ethics, to the project of coming to understand how to live well.

Janus

17.9kI was thinking more along the lines of pre-critical ancient schools of philosophy with their (unquestioned) doctrines and spiritual exercises as described by Pierre Hadot. It would be closer to ethics, to the project of coming to understand how to live well.

I agree that other disciplines will feed into that, including science. It seems, though, that the sciences of, for example, nutrition and exercise have more bearing on the question of how best to live than QM or cosmology. -

jgill

4k

jgill

4k

Very nice presentation. Metaphysics in the sciences goes on all the time, although most come from actual scientists.

I was curious about mathematical metaphysics, thinking I had some inkling of what that might be. I have in the past thought of infinitesimals in this light, but searching I came across Mathematical Metaphysics by a prominent academic philosopher and a PhD math student. It is both dense and lengthy, hallmarks of the profession I assume, and seems to boil down to something akin to Tegmark's Mathematical

Universe. Every object, physical or otherwise is mathematical, and defined by a structure in which it resides. But I lost interest and perseverance after a few pages of the 32 page paper.

Lengthy, dense papers appear in math journals as well, and they sometimes owe their lengths and convoluted nature to attempts to fill every intellectual crack so no one else can benefit from their discoveries and/or to answer all questions in advance. But it's late and I wither and dither. -

Pantagruel

3.6k

Pantagruel

3.6k

Very nice presentation. Metaphysics in the sciences goes on all the time, although most come from actual scientists. — jgill

I second that. Nicely stated. :clap: -

Fooloso4

6.2k

Fooloso4

6.2k

Aristotle sums up the ancient position on knowledge when he says that all men naturally desire knowledge. Bacon marks the position of modern philosophy when he declares that knowledge is power. -

plaque flag

2.7k:up:

plaque flag

2.7k:up:

Also (as I'm sure you know) there's 'masters and possessors of nature' from Descartes.

Feuerbach finds it (this basically Luciferian humanism) implicit in Christianity's theism.

But if man is the end of creation, he is also the true cause of creation, for the end is the principle of action. The distinction between man as the end of creation, and man as its cause, is only that the cause is the latent, inner man, the essential man, whereas the end is the self-evident, empirical, individual man, – that man recognizes himself as the end of creation, but not as the cause, because he distinguishes the cause, the essence from himself as another personal being.

But this other being, this creative principle, is in fact nothing else than his subjective nature separated from the limits of individuality and materiality, i.e., of objectivity, unlimited will, personality posited out of all connection with the world, – which by creation, i.e., the positing of the world, of objectivity, of another, as a dependent, finite, non-essential existence, gives itself the certainty of its exclusive reality. The point in question in the Creation is not the truth and reality of the world, but the truth and reality of personality, of subjectivity in distinction from the world. The point in question is the personality of God; but the personality of God is the personality of man freed from all the conditions and limitations of Nature. Hence the fervent interest in the Creation, the horror of all pantheistic cosmogonies. The Creation, like the idea of a personal God in general, is not a scientific, but a personal matter; not an object of the free intelligence, but of the feelings; for the point on which it hinges is only the Guarantee, the last conceivable proof and demonstration of personality or subjectivity as an essence quite apart, having nothing in common with Nature, a supra- and extra-mundane entity.

Man distinguishes himself from Nature. This distinction of his is his God: the distinguishing of God from Nature is nothing else than the distinguishing of man from Nature.

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/feuerbach/works/essence/ec10.htm -

Leontiskos

5.6kIs that the task of the philosopher, or of the engineer, technologist and scientist? — Quixodian

Leontiskos

5.6kIs that the task of the philosopher, or of the engineer, technologist and scientist? — Quixodian

I agree.

Of course, the fact that Bacon helped shift the Western trajectory towards the manipulation of nature is not in dispute. Indeed, it is probably the most common narrative in the Western history of thought. But I haven't quite figured out what it has to do with this thread. Perhaps if the Baconians are philosophers then philosophy retains its relevance? Yet given that the OP talks about "the direction of philosophy and science since Bacon," how then have we arrived at the claim that post-Baconian science is philosophy itself (or else the devoted spouse of philosophy)? -

Wayfarer

26.1kMy answer to the question would be framed in terms of my quest to understand the dominance of scientific materialism in modern culture. That is of course a meta-philosophical quest, a ‘philosophy of philosophy’, rather than something within philosophy itself. Some of the relevant books I have read about it are Theological Origins of Modernity, Michael Allen Gillespie, and (parts of) A Secular Age, Charles Taylor. It’s a dialectical process which has taken centuries to unfold and is still unfolding.

Wayfarer

26.1kMy answer to the question would be framed in terms of my quest to understand the dominance of scientific materialism in modern culture. That is of course a meta-philosophical quest, a ‘philosophy of philosophy’, rather than something within philosophy itself. Some of the relevant books I have read about it are Theological Origins of Modernity, Michael Allen Gillespie, and (parts of) A Secular Age, Charles Taylor. It’s a dialectical process which has taken centuries to unfold and is still unfolding. -

Wayfarer

26.1kAristotle sums up the ancient position on knowledge when he says that all men naturally desire knowledge. Bacon marks the position of modern philosophy when he declares that knowledge is power. — Fooloso4

Wayfarer

26.1kAristotle sums up the ancient position on knowledge when he says that all men naturally desire knowledge. Bacon marks the position of modern philosophy when he declares that knowledge is power. — Fooloso4

Aristotle, and Greek philosophy generally, also differentiated different kinds of knowledge, did they not? Phronesis, techne, episteme, and so forth - which had different attributes and spheres. Many of those distinctions seem to have become blurred. And Bacon's re-definition of knowledge as power easily morphs into knowledge as instrumental utility, thenceforth the entire 'instrumentalisation of reason' trend criticized by the Frankfurt School. -

Janus

17.9kI think the scientific revolution was fueled by advances in mathematics. — Fooloso4

Janus

17.9kI think the scientific revolution was fueled by advances in mathematics. — Fooloso4

Possibly advances in mathematics were catalyzed by the discovery of fossil fuels, but I do agree that mathematics played a part, particularly in physics and chemistry.

Would the scientific revolution, considered as being predominately an industrial and technological revolution, have been possible, or if possible, nearly as rapid, without the discovery of fossil fuels? -

Paine

3.2kIt seems to me that if the becoming has no end then there can be no ultimate convergence. — Leontiskos

Paine

3.2kIt seems to me that if the becoming has no end then there can be no ultimate convergence. — Leontiskos

This prompts me to think of Heraclitus. Everything is Becoming because the past is as Eternal as the Future. So, there is a nature that brings about what we encounter but we are limited in our means to understand it.

It is interesting that Aristotle said that the Platonic views were a reaction to this idea. Aristotle's opinion does put Platonic dialogues like Craylus into a particular perspective, where the struggle between convention and nature is underway. -

Leontiskos

5.6k

Leontiskos

5.6k

Yes, that makes good sense to me. I am familiar with Taylor but will have to look into Gillespie.

---

Yes, exactly right. I was thinking about Heraclitus as well. I will have to revisit Cratylus. -

jgill

4kPossibly advances in mathematics were catalyzed by the discovery of fossil fuels — Janus

jgill

4kPossibly advances in mathematics were catalyzed by the discovery of fossil fuels — Janus

Hmmm. Never thought of that. More like the surge of science in the 14th century, including measuring velocity over short periods of time, then resurrecting the ancient Greeks' notions of approximating volumes of objects by adding very small parts. After the firming up of calculus things moved pretty fast. -

Wayfarer

26.1kbut I do agree that mathematics played a part, particularly in physics and chemistry. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.1kbut I do agree that mathematics played a part, particularly in physics and chemistry. — Janus

I had thought that Descartes’ discovery of algebraic geometry - the idea of dimensional co-ordinates - was of absolutely fundamental importance in the ‘new sciences’. That, allied with Galileo’s mathematicization of nature, and the discovery of universal laws of motion, all of which preceded the mechanised harnessing of fossil fuels (although that no doubt was an enormous economic factor.) -

Janus

17.9kThe claim I am resiling from is that possibly developments in mathematics were catalyzed by the discovery of fossil fuels. Of course, there was always wood as a fuel, and the discovery of fire was obviously important but happened eons before the advent of science as we understand it. Technology, on the other hand has been progressing from the earliest human times. There was apparently a precursor to the steam engine in the first century AD. I still believe that the development of science would have been much slower without fossil fuels, but of course I wasn't wishing to deny the importance of mathematics and geometry in science.

Janus

17.9kThe claim I am resiling from is that possibly developments in mathematics were catalyzed by the discovery of fossil fuels. Of course, there was always wood as a fuel, and the discovery of fire was obviously important but happened eons before the advent of science as we understand it. Technology, on the other hand has been progressing from the earliest human times. There was apparently a precursor to the steam engine in the first century AD. I still believe that the development of science would have been much slower without fossil fuels, but of course I wasn't wishing to deny the importance of mathematics and geometry in science. -

plaque flag

2.7kI still believe that the development of science would have been much slower without fossil fuels, but of course I wasn't wishing to deny the importance of mathematics and geometry in science. — Janus

plaque flag

2.7kI still believe that the development of science would have been much slower without fossil fuels, but of course I wasn't wishing to deny the importance of mathematics and geometry in science. — Janus

:up:

Pinker's Enlightenment Now ! (however one feels about its tone) is great on the importance of any radical change in the cost of energy. In a certain sense, energy 'is' food. Energy, like money, is exchangeable for whatever we need, in other words. So all kinds of leisure and scientific equipment become possible as a direct result of cheaper energy --- so I very much agree with you. And then scientific progress decreases the cost of energy further, and so on. Exponential timebinding primates. We 'had' to end up where we are, threatening our own biosphere, caught up in a prisoner's dilemma.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum