-

plaque flag

2.7kI present an ontology that is flat because it is not stacked (two layers) like dualism. Nor is mentality or physicality given priority. A flat ontology rejects any ontology of transcendence or presence that privileges one sort of entity as the origin of all others and as fully present to itself.. Then we have the related plane metaphor from another source : Deleuze, however, employs the term plane of immanence as a pure immanence, an unqualified immersion or embeddedness, an immanence which denies transcendence as a real distinction, Cartesian or otherwise. Pure immanence is thus often referred to as a pure plane, an infinite field without substantial or consistent division.

plaque flag

2.7kI present an ontology that is flat because it is not stacked (two layers) like dualism. Nor is mentality or physicality given priority. A flat ontology rejects any ontology of transcendence or presence that privileges one sort of entity as the origin of all others and as fully present to itself.. Then we have the related plane metaphor from another source : Deleuze, however, employs the term plane of immanence as a pure immanence, an unqualified immersion or embeddedness, an immanence which denies transcendence as a real distinction, Cartesian or otherwise. Pure immanence is thus often referred to as a pure plane, an infinite field without substantial or consistent division.

It is rationalist in its emphasis that all entities are linked inferentially, with causality being understood in terms of licensed inferences. We decide (argue about) when causality is appropriately attributed. The enabling conditions for any ontology are also assumed and necessarily central.

Now flat and rationalist come together. We already explain going to the dentist (“physical”) in terms of a toothache (“mental”). We already explain hearing music (“mental”) in terms of hammers on strings (“physical”). We might explain going off the road by a hallucination and that hallucination by the ingestion of a drug. Given all of these typical inferential connections between the sacred categories, the mental/physical dyad loses its prestige. A single 'continuous' blanket ontology becomes possible, with the nonalienated immanent (even centrally located ) rational community as the spider on the web.

questions

Does the attempt to demystify the mind/matter dyad make sense ?

Is this ontology suffocating ? Do we prefer to be outside peeping in ? Hegel wrote of the fear of truth masquerading as the fear of error.

Is the rampant humanism disturbing ? Is such humanism created here or merely unveiled? I think I'm just making the rationalism that was always central explicit. I grant that embracing it gives it a different feel. But this is also a thought experiment, a topic that'll hopefully be fun.

Join in me in....you guessed it...conversational research. -

Wayfarer

26.1kDoes the attempt to demystify the mind/matter dyad make sense ? — plaque flag

Wayfarer

26.1kDoes the attempt to demystify the mind/matter dyad make sense ? — plaque flag

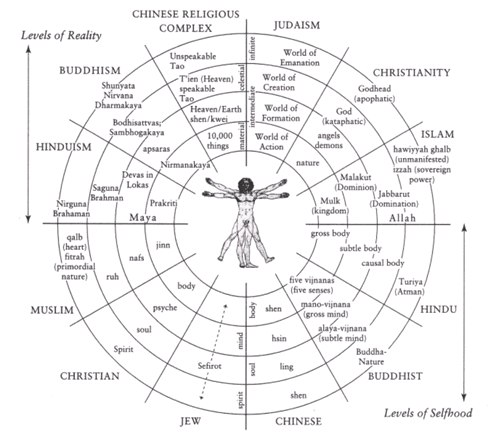

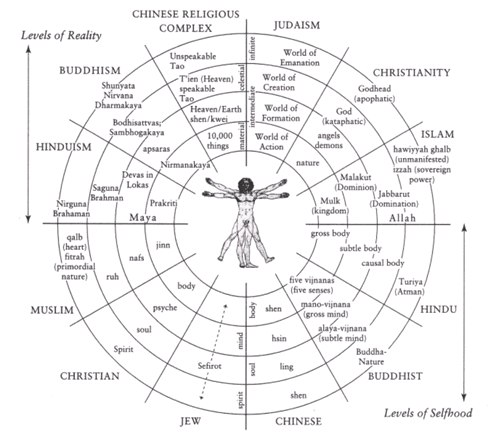

No, I don't think so. I there has to be a conception of levels or modes or domains of being. Traditionally that was cast in terms of the chain of being, but it survived even into the 17th Century:

In contrast to contemporary philosophers, most 17th century philosophers held that reality comes in degrees—that some things that exist are more or less real than other things that exist. At least part of what dictates a being’s reality, according to these philosophers, is the extent to which its existence is dependent on other things: the less dependent a thing is on other things for its existence, the more real it is.

I've been listening to installments in The Meaning Crisis by John Vervaeke (which I recommend). He too refers to the necessity of levels of being which he adapts from neoplatonist ontology. Speaking of which, here's a useful Huston Smith graphic depiction of levels of being in various traditional philosophies:

-

plaque flag

2.7kNo, I don't think so. I there has to be a conception of levels or modes or domains of being. Traditionally that was cast in terms of the chain of being, but it survived even into the 17th Century: — Quixodian

plaque flag

2.7kNo, I don't think so. I there has to be a conception of levels or modes or domains of being. Traditionally that was cast in terms of the chain of being, but it survived even into the 17th Century: — Quixodian

Note that I place rationality at the center. One might want to call this 'mind,' but the rational community is embodied and share a world of entities that they understand inferentially. This understanding just is the dynamic negotiated conceptual structure/aspect of the lifeworld. So it's more like a reason that's the glue of the world, the articulated spine of reality.The normativity of giving and asking for reasons is central, for this community is indeed a necessary being ---implicit in the very idea of 'serious' 'ambitious' 'scientific' philosophy. The real is rational and the rational is real. That's the 'faith' of philosophy or the sigil on its banners. -

plaque flag

2.7kI there has to be a conception of levels or modes or domains of being. — Quixodian

plaque flag

2.7kI there has to be a conception of levels or modes or domains of being. — Quixodian

I should add that it's only flat in the sense that nothing is stacked on anything else. It's given as an entire blanket. Entities and categories get their meaning structurally, relationally. People still value things differently. But this need not appear in the logical structure. I'm intentionally leaving the details unspecified. I want to give only the skeleton, leave out everything that's contingent.

Any postulated higher beings would have to be justified in the rational conversation. Basically rationality itself is god in this basically humanist conception. But what humans are is largely what they determine themselves to be. -

chiknsld

314Basically rationality itself is god in this basically... — plaque flag

chiknsld

314Basically rationality itself is god in this basically... — plaque flag

A sound philos must always rely on sound logic, but at least you are making an effort! -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Is the rampant humanism disturbing ? Is such humanism created here or merely unveiled? I think I'm just making the rationalism that was always central explicit. I grant that embracing it gives it a different feel.

Maybe. From the dawn of philosophy through Kant's noumena, we see a strong tendency to posit a distinction between the word we live in and something more real, and naive realism itself posits an external world that is distinct from us. I think we possess an inborn tendency to use our senses to cross check each other, to avoid illusion. We also have inborn tendency to posit such externalities as there is some selection advantage in "taking these things seriously." -

plaque flag

2.7kFrom the dawn of philosophy through Kant's noumena, we see a strong tendency to posit a distinction between the word we live in and something more real, and naive realism itself posits an external world that is distinct from us. — Count Timothy von Icarus

plaque flag

2.7kFrom the dawn of philosophy through Kant's noumena, we see a strong tendency to posit a distinction between the word we live in and something more real, and naive realism itself posits an external world that is distinct from us. — Count Timothy von Icarus

For me there's a semantic issue here. What can we mean by 'more real' ? Doesn't experience give our words meaning ? -

plaque flag

2.7kThe real is rational and the rational is real. That's the 'faith' of philosophy — plaque flag

plaque flag

2.7kThe real is rational and the rational is real. That's the 'faith' of philosophy — plaque flag

Just want to say that I'm giving this famous aphorism a slightly different meaning in its new context. Here it's not about history but attitude and belief.

The real is rational. We meet it courageously as something we can and ought to make sense of. There's what Nietzsche might call Socratic optimism in this. Our 'Socrates' here might admit that this is the unjustified existential decision-- the getting on the ladder.

The rational is real. We accept as real only what we can make sense of. We exclude unjustified claims from our relatively settled beliefs. This doesn't mean we aren'tforcedprivileged to live in a 'field of possibility.' -

plaque flag

2.7kMind may no longer be conceived as a self-contained field, substantially differentiated from body (dualism), nor as the primary condition of unilateral subjective mediation of external objects or events (idealism). Thus all real distinctions (mind and body, God and matter, interiority and exteriority, etc.) are collapsed or flattened into an even consistency or plane, namely immanence itself, that is, immanence without opposition.

plaque flag

2.7kMind may no longer be conceived as a self-contained field, substantially differentiated from body (dualism), nor as the primary condition of unilateral subjective mediation of external objects or events (idealism). Thus all real distinctions (mind and body, God and matter, interiority and exteriority, etc.) are collapsed or flattened into an even consistency or plane, namely immanence itself, that is, immanence without opposition.

http://faculty.umb.edu/gary_zabel/Courses/Spinoza/Texts/Plane%20of%20immanence%20-%20Wikipedia,%20the%20free%20encyclopedia.htm

To me this falls out of something like Brandom's inferentialism and Hegel's holism. The finite entity has no genuine being --- a mere superstition or useful fiction (map, model). The normative communal subject does turn out to be central, but such a subject is only intelligible when embodied within a world (though the details are left to be determined by that community.)

We automatically understand all entities at once systematically, relationally. A disconnected entity is an empty entity, a meaningless entity. Your nostalgia or lumbago is in my world too (our world) because we can both include it in the justification and challenging of claims. Quaternions are as real as swans, existing on/from the same network. Promises and termites and forgotten umbrellas. Thereality-bestowingreality-acknowledging vortex at the center is the rational discussion ---which was always tacitly central as legislator but often misunderstood itself as peeping in the from the outside. -

plaque flag

2.7kA sound philos must always rely on sound logic, but at least you are making an effort! — chiknsld

plaque flag

2.7kA sound philos must always rely on sound logic, but at least you are making an effort! — chiknsld

I invite you to show me the error of ways. No irony intended. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Right, and I'm inclined to agree with you that this might not be a good way to think of things at all. But this is certainly a way in which people often tend to think about things. For Plato, the universal represents a higher truth, and a similar theory can be traced back to Memphite Theology prior to Plato. The noumenal, being qua being, the "view from nowhere," also supposes a reality that is causally and ontologically prior to the world of experience.

My point would simply be that the ubiquity of philosophies that focus on the difference between the world of experience and the world of ultimate reality from which experience springs, might tell us something about ourselves, even if we think that view is ultimately misguided. Such views aren't merely products of Western philosophy. You see it in the doctrine of Maya in Shankara, in Lao Tzu, etc.

This parallels a simpler ubiquity in human behavior. When we are confused about what we are experiencing, we use our senses to "cross check" one another. When a stick appears to be bent by water, we stick our hand in to find out the "truth of the matter." When we can't tell if a flower is a real flower or an artful fake, we bring it to our nose. When an optical illusion is particularly effective at creating a sense of depth where there is none, we check by touching it.

My hunch is that this is why our perceptions of different types of sensation remain so incredibly distinct. We don't have the problem of mistaking touch for sound or sound for sight. Synesthesia exists, but it is mild; I have never heard of people completely unable to disambiguate their senses. Synesthesia also appears to confer a lot of benefits, but a loss of ability to "cross-check" between the senses might explain why it remains uncommon.

Since our sensory systems are prone to all sorts of "errors" independently, we have an inborn tendency to bring in other resources to get to the bottom of apparent discrepancies in the world. It's not hard to see how this ties into natural selection and survival advantage. And hence, we seem attuned to create of a model of the world that is "out there," and which is distinct from our experience of it. I can't think of any primitive cultures that espouse idealism; early myth tends to focus on an external world being created from thing things of everyday experience, man from mud and dust, etc.

So, per your quote from Hegel, yes I think there is an element of fear here. There is a fear that if one equates experience with being they shall fail to account for sensory illusions and meet with disaster. There are costs to fleeing from sticks that one mistakes for venomous snakes and even greater costs for mistaking venomous snakes for sticks. Our capacity for attempting to distinguish between sensation, incoming signal, and the actuality of the source of said signal, seems to be extremely basic, biologically primitive. That is, at a basic, unconscious, primitive level, we already see functional cross-checks going on in how the visual cortex areas process data from the optic nerve.

To my mind, this explains why reactions against subjective idealism are so often reflexive, knee jerk. There is also a theory that, because humans are social animals, we come equipped with an ability to simulate how the world and our own actions appear to other people. This too suggests an objective world that stands "over there."

But I don't think this dooms a flat ontology, it just makes it hard to explain. Here is one of the better efforts:

In §24 of the Encyclopedia Logic [Hegel] claims that “logic coincides with metaphysics, with the science of things grasped in thoughts” (EL 56/81), and in the introduction to the Logic he maintains that “the objective logic . . . takes the place . . . of former metaphysics which was intended to be the scientific construction of the world in terms of thoughts alone” (SL 63/1: 61). Hegel also emphasizes the metaphysical character of the Logic by asserting that its subject matter is the logos, “the reason of that which is”: “it is least of all the logos which should be left outside the science of logic” (SL 39/1: 30)…

Hegel does not claim that ontological structures are known in the Logic precisely as they occur in nature. The Logic conceives such structures in abstraction from space, time, and matter first of all, and the Philosophy of Nature then examines how such structures manifest themselves in space and time. Hegel’s claim that conceptual and syllogistic form is to be found in nature (or in “all things”) should not therefore be taken to blur the distinction between the Logic and the Philosophy of Nature. What that claim does make clear, however, is that for Hegel “concept” and “syllogism” are forms inhering in what there is and are not just forms in terms of which we think; they are ontological and not merely logical structures.

---

Hegel’s arguments in support of the claim that thought understands not just the objects of our experience but being itself can be regarded as forming his own Transcendental Deduction....

There are two intimately related arguments at the heart of Hegel’s Transcendental Deduction. After Kant’s critical turn, Hegel maintains, the logician is no longer justified in taking for granted any rules, laws, or concepts of thought (SL 43/1: 35). Indeed, the logician cannot take for granted anything at all about thought except thought’s own simple being. In the science of logic, therefore, we may begin from nothing more determinate than the sheer being of thought itself—thought as sheer being.

...The principal difference between Descartes and Hegel, of course, is that for Hegel the process of suspending all that thought has previously taken for granted about itself leaves us not with the recognition that I am but with the indeterminate thought of thought itself as sheer being.

Hegel’s second argument is equally simple but starts from the idea of “being” rather than from thought. If we are to be thoroughly self-critical, we cannot initially assume that being is anything beyond the being of which thought is minimally aware. We may not assume that being stands over against thought or eludes thought but must take being to be the sheer immediacy of which thought is minimally aware—because that is all that the self-critical suspension of our presuppositions about being and thought leaves us with. A thoroughly selfcritical philosopher has no choice, therefore, but to equate being with what is thought and understood. Any other conception of being—in particular, one that regards being as possibly or necessarily transcending thought—is simply not warranted by the bare idea of being as the “sheer-immediacy-of-which-thoughtis-minimally-aware” from which we must begin.

First, we are aware of being for no other reason than that we think; thought is thus the “condition” of our awareness of being. This is Hegel’s quasi-Kantian principle. Second, thought is minimally the awareness or intuition of being itself. This is Hegel’s quasiSpinozan principle. These two principles dovetail in the single principle that the structure of being is the structure of the thought of being and cause Hegel to collapse ontology and logic into the new science of ontological logic. 31

Hegel acknowledges that there is a difference between thought and being: being is what it is in its own right and is not there only for conscious thought. Moreover, as we learn in the course of the Logic, being does, after all, turn out to constitute a realm of objects (“over there” and all around us). Hegel insists, however, that we may not begin by assuming that being is quite separate from thought.

Houlgate - The Opening of Hegel’s Logic From Being to Infinity pp. 116 & 129-130

Actually, there is some pretty interesting parallels between Floridi's information theory based maximally portable ontology and Hegel's objective logic, despite the fact that they come from pretty different places, but I have not yet put together my thoughts on that. -

plaque flag

2.7kFor Plato, the universal represents a higher truth — Count Timothy von Icarus

plaque flag

2.7kFor Plato, the universal represents a higher truth — Count Timothy von Icarus

For what it's worth, I embrace the quest for (relatively) atemporal universal truth. I think 'anti-philosophers' usually turn out to be just philosophers, even if they don't want to see it or prefer a different packaging.

My point would simply be that the ubiquity of philosophies that focus on the difference between the world of experience and the world of ultimate reality from which experience springs, might tell us something about ourselves, even if we think that view is ultimately misguided. Such views aren't merely products of Western philosophy. You see it in the doctrine of Maya in Shankara, in Lao Tzu, etc. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Sure, but note that 'rationalism' is largely a reaction to the human default of superstition and confusion. Sophisticated defenders of religion forget that crude religion would have them on the gallows beside the atheistic rationalists. Peacefully working out what part of our legacy is worth recontextualizing is the luxury of an essentially reasonable and free community. What I've presented above doesn't exclude the postulation of 'supernatural' entities, though they'd have to be woven into an inferential nexus with the proper justifications (losing in some sense their 'supernatural' flavor.) -

plaque flag

2.7k

plaque flag

2.7k

This part of the quote is what I have in mind.

A thoroughly selfcritical philosopher has no choice, therefore, but to equate being with what is thought and understood. Any other conception of being—in particular, one that regards being as possibly or necessarily transcending thought—is simply not warranted by the bare idea of being as the “sheer-immediacy-of-which-thought-is-minimally-aware” from which we must begin.

This is also close to an interpretation of Husserl that I like (Zahavi's). Not 'warranted' and seemingly questionable semantically. We 'rational ones' insist on knowing what we are talking about. For Husserl, reality isn't given all at once, but it is always at least potentially experienceable --or we don't know what we are saying.

It might be worth stressing (with Feuerbach) that conceptuality is just one 'aspect' or 'dimension' of Reality which is also given to the body through nose, eyes, skin, and so on. Reality is not just ideas, but ideas are like intentional nodes or centers that articulate or organize it. -

plaque flag

2.7kWhat's most offensive in this rationalism is probably the Luciferian humanism. Sartre writes that we are condemned to be free. Does the world lose magic when we finally stand up and demand from the gods that they justify their continuing existence ? Tell us why they should keep their jobs?

plaque flag

2.7kWhat's most offensive in this rationalism is probably the Luciferian humanism. Sartre writes that we are condemned to be free. Does the world lose magic when we finally stand up and demand from the gods that they justify their continuing existence ? Tell us why they should keep their jobs? -

plaque flag

2.7kTo me it seems that we often literally forget ourselves and our own 'space of reasons' as we do philosophy. The transparency of our own subjectivity, often a great thing in other contexts, is disastrous ontologically.

plaque flag

2.7kTo me it seems that we often literally forget ourselves and our own 'space of reasons' as we do philosophy. The transparency of our own subjectivity, often a great thing in other contexts, is disastrous ontologically.

https://sites.pitt.edu/~rbrandom/Texts/Knowledge%20and%20the%20Social%20Articulation%20of%20the%20Space%20of%20Reasons.pdfWhat is the difference between a parrot who is disposed reliably to respond differentially to the presence of red things by saying "Raawk, that's red," and a human reporter who makes the same noise under the same circumstances? Or between a thermometer that responds to the temperature's dropping below 70 degrees by reporting that fact by moving the needle on its output dial and a human reporter who makes a suitable noise under the same conditions?

By hypothesis both reliably respond to the same stimuli, but we want to say that humans do, and the parrots and thermometers do not, respond by applying the concepts red or 70 degrees. The parrot and the thermometer do not grasp those concepts, and so do not understand what they are 'saying'. That is why we ought not to consider their responses as expressing beliefs: the belief condition on knowledge implicitly contains an understanding condition. The Sellarsian idea with which McDowell begins is that this difference ought to be understood in terms of the space of reasons. The difference that makes a difference in these cases is that for the human reporters, the claims "That's red," or "It's 70 degrees out," occupy positions in the space of reasons---the genuine reporters can tell what follows from them and what would be evidence for them.

This practical know-how --- being able to tell what they would be reasons for and what would be reasons for them--- is as much a part of their understanding of 'red' and '70 degrees' as are their reliable differential responsive dispositions. And it is this inferential articulation of those responses, the role they play in reasoning, that makes those responsive dispositions dispositions to apply concepts. If this idea is right, then nothing that can't move in the space of reasons --- nothing that can't distinguish some claims or beliefs as justifying or being reasons for others --- can even count as a concept user or believer, never mind a knower: it would be in another line of work altogether. — Brandom

A flat ontology is largely a response to the recognition of the huge role that inferential relationships play in meaning. Granted our autonomy-fired mission to articulate the conceptual aspect of reality critically, which includes justifying our claims by showing them as conclusions of sound arguments, the inferential role of concepts can hardly be some secondary afterthought. -

Possibility

2.8kI can’t say that I agree with ‘flat’ as an accurate descriptor for the ontology you propose here (although I get the reference), nor do I consider any humanist or rationalist ontology to meet your own criteria of not being stacked or privileging one entity over another. Would you consider this to be performative contradiction?

Possibility

2.8kI can’t say that I agree with ‘flat’ as an accurate descriptor for the ontology you propose here (although I get the reference), nor do I consider any humanist or rationalist ontology to meet your own criteria of not being stacked or privileging one entity over another. Would you consider this to be performative contradiction?

If what you’re striving for is immanence without transcendence, then you’d need a triadic relational structure without pre-existing relata. Consider: rationality (logic) - quality (ideal) - energy (affect). It presents rationality as mutually fundamental, while also allowing for its limitations and doing away with humanism and its hubris without ‘suffocating’ our capacity. And it’s simultaneously dynamic, stable and symmetrical. -

chiknsld

314For what it's worth, I embrace the quest for (relatively) atemporal universal truth. — plaque flag

chiknsld

314For what it's worth, I embrace the quest for (relatively) atemporal universal truth. — plaque flag

Keep searching buddy! :nerd: -

plaque flag

2.7k

plaque flag

2.7k

Presumably you imply the relatively atemporal truth that such truth is impossible. That's the problem with lazy poses. -

plaque flag

2.7knor do I consider any humanist or rationalist ontology to meet your own criteria of not being stacked or privileging one entity over another. — Possibility

plaque flag

2.7knor do I consider any humanist or rationalist ontology to meet your own criteria of not being stacked or privileging one entity over another. — Possibility

I think (I hope) that my OP made it clear that ontology itself (the stage and its ontological actors) is the necessary spider at the center of the web. The primary use of 'flat' is to emphasize the claim that 'mental' and 'physical' entities have always already been inferentially connected in order to be meaningful in the first place. [ OK, I'm not 100% an inferentialist, but ...]

This contributes toward motivating a phenomenological indirect realism which is another aspect of that flatness. Your hallucination is part of my world along with my desk lamp and . Though noninferential access to such entities may vary from person to person, with you having a privileged 'view' of your toothache, our inferential access to such entities is (ideally) 'transpersonal' (no private language, inferentialist semantics, etc.) A person born blind can know about color and yet has never seen, inasmuch as knowledge is understood in terms of justified true belief.

The 'rationalism' is not so much a nerdy celebration of 'facts and logic' as a level or moment of philosophy's dialectically achieved 'self-consciousness.' The ontologist articulates the real through/with justified claims. Small wonder then that inferential role semantics becomes so tempting. -

Possibility

2.8kI think (I hope) that my OP made it clear the ontology itself (the stage and its ontological actors) is the necessary spider at the center of the web. — plaque flag

Possibility

2.8kI think (I hope) that my OP made it clear the ontology itself (the stage and its ontological actors) is the necessary spider at the center of the web. — plaque flag

You mean this?

A single 'continuous' blanket ontology becomes possible, with the nonalienated immanent (even centrally located ) rational community as the spider on the web. — plaque flag

…it wasn’t clear. -

Wayfarer

26.1kAny postulated higher beings would have to be justified in the rational conversation — plaque flag

Wayfarer

26.1kAny postulated higher beings would have to be justified in the rational conversation — plaque flag

Isn't what you mean by 'rational' in this thread empirically or scientifically justifiable? I note that my entry reflexively provokes the objection to 'postulated higher beings'. I suppose that means that what I wrote 'sounds religious'. I will admit to that, I do often 'sound religious', in that I question the secular physicalist consensus. But can't see any choice but to do that in order to arrive at a meaningful ontology. And that inevitably provokes this kind of response. That's a kind of unstated premise in the description 'flat' - no levels!

I've been listening to the work of a Canadian professor of psychology and cog. sci., John Vervaeke, who is gathering a large popular following on Youtube (links to a series of lectures.) His starting point was what he calls 'the meaning crisis' which is manifest in almost every aspect of today's culture, and his lectures encompass many religious or spiritual themes, but he (and his many collaborators) want to stay grounded in naturalism and remain fully cognizant of science. But given that, he recognises the need for levels of being, which correspond also to different levels and kinds of knowing, to which end he adopts and adapts a version of neoplatonic ontology, culminating in what he describes in a later series of talks as 'transcendent naturalism' (that is, naturalism not confined to materialist reductionism). I won't try and break it down or present it here but suffice to note that the earlier graphic I posted would not, I think, be incompatible with the kind of structures he's proposing.

The Sellarsian idea with which McDowell begins is that this difference ought to be understood in terms of the space of reasons. — Brandom

I've explored Sellars 'space of reasons' a little (although I find Sellars very difficult reading). Suffice to say, I'm persuaded by it. @Pierre-Normand pointed out an interesting book on a similar theme, Rational Causation, by Eric Marcus (ref):

We explain what people think and do by citing their reasons, but how do such explanations work, and what do they tell us about the nature of reality? Contemporary efforts to address these questions are often motivated by the worry that our ordinary conception of rationality contains a kernel of supernaturalism—a ghostly presence that meditates on sensory messages and orchestrates behavior on the basis of its ethereal calculations. In shunning this otherworldly conception, contemporary philosophers have focused on the project of “naturalizing” the mind, viewing it as a kind of machine that converts sensory input and bodily impulse into thought and action. Eric Marcus rejects this choice between physicalism and supernaturalism as false and defends a third way.

I haven't fully explored that book, either, but suffice to say for this post, that I think the faculty of rational judgement is indeed 'ethereal' or at least incorporeal - and that this is the original meaning of the 'rational soul' in Aristotle and the Western tradition. It was originally understood as the faculty which discerns the real, albeit in a sense that was subsequently lost to contemporary culture (although arguably preserved in Hegel). That faculty, to grasp meaning or essences, is associated with 'nous' which is the source of rationality.

But the salient point here is that such an ability is 'above nature', so to speak. It is 'above' it, in the same sense that the explanans is above the explanadum - it grasps the underlying causes (logos, in the archaic sense) which make general observations, and therefore explanatory principles, possible. So, I'm persuaded that this faculty is linked to the ability to grasp universals (which have generally been rejected by philosophers since the Enlightenment). For Aristotle, this faculty - 'nous' - was distinct from the processing of sensory perception, including the use of imagination and memory, which other animals possess. For him, nous is connected to discussion of how the human mind grasps definitions in a consistent and communicable way (hence universals as a theory of predication) and whether the mind possesses an innate potential to understand them. And in the broader platonist tradition (philosophy generally) there is undoubtedly an heirarchy of being and knowing, but which has been generally occluded by the over-emphasis on empiricism.

-

plaque flag

2.7kIf what you’re striving for is immanence without transcendence, then you’d need a triadic relational structure without pre-existing relata. Consider: rationality (logic) - quality (ideal) - energy (affect). It presents rationality as mutually fundamental, while also allowing for its limitations and doing away with humanism and its hubris without ‘suffocating’ our capacity. And it’s simultaneously dynamic, stable and symmetrical. — Possibility

plaque flag

2.7kIf what you’re striving for is immanence without transcendence, then you’d need a triadic relational structure without pre-existing relata. Consider: rationality (logic) - quality (ideal) - energy (affect). It presents rationality as mutually fundamental, while also allowing for its limitations and doing away with humanism and its hubris without ‘suffocating’ our capacity. And it’s simultaneously dynamic, stable and symmetrical. — Possibility

I'd be glad to hear more about this. I neglected it at first as I was caught up defending my 'flat' metaphor. -

plaque flag

2.7k

plaque flag

2.7k

In this particular thread, I'm talking about both inferential role semantics (actual inferential norms) and the crucial role they play for philosophers subject to the rationality of the ideal communication community.Isn't what you mean by 'rational' in this thread empirically or scientifically justifiable? — Quixodian

I was strongly inspired by Brandom inferentialism. The first insight is that much of a concept's meaning (some would say all) is to be found structurally-relationally in the norms that govern inferences involving that concept.

Note also that philosophy determines the real rationally. I use ontology to emphasize a 'scientific' as a opposed to 'esoteric' conception, but 'scientific' only means the ideal communication community thats founded on autonomy.

..a participant in a genuine argument is at the same time a member of a counterfactual, ideal communication community that is in principle equally open to all speakers and that excludes all force except the force of the better argument. Any claim to intersubjectively valid knowledge (scientific or moral-practical) implicitly acknowledges this ideal communication community as a meta-institution of rational argumentation, to be its ultimate source of justification

Finally we see that the entities whose nature are to be determined by ontology are already inferentially linked. Indeed, for the inferentialist they only have meaning in terms of one another ---structurally. Some of the motive for dualism is obliterated.

[In other threads I try to explain how the intentional object and the dramaturgical-discursive subject always necessarily being worldly points to direct realism --- to consciousness understood in terms of the being of the world through or for a perspective. This further flattens ye olde dualism. ]

But I'm not a total inferentialist. I think the system is grounded by what Husserl describes as bodily givenness and categorial intution. I can see that my car keys are on the table. I can articulate this seeing. I see that-my-car-keys-are-on-the-table. This also helps explains Popper's 'basic statements' and why (in my view) a measurement requires a human being. -

plaque flag

2.7kBut can't see any choice but to do that in order to arrive at a meaningful ontology. And that inevitably provokes this kind of response. That's a kind of unstated premise in the description 'flat' - no levels! — Quixodian

plaque flag

2.7kBut can't see any choice but to do that in order to arrive at a meaningful ontology. And that inevitably provokes this kind of response. That's a kind of unstated premise in the description 'flat' - no levels! — Quixodian

The issue for me is really just social-rational versus esoteric-private. We could all agree to a God, but that God would still be determined rationally. So in this sense rationality is the 'real god' (the final authority.) -

plaque flag

2.7kBut given that, he recognises the need for levels of being, which correspond also to different levels and kinds of knowing, to which end he adopts and adapts a version of neoplatonic ontology, culminating in what he describes in a later series of talks as 'transcendent naturalism' (that is, naturalism not confined to materialist reductionism). — Quixodian

plaque flag

2.7kBut given that, he recognises the need for levels of being, which correspond also to different levels and kinds of knowing, to which end he adopts and adapts a version of neoplatonic ontology, culminating in what he describes in a later series of talks as 'transcendent naturalism' (that is, naturalism not confined to materialist reductionism). — Quixodian

To me there's nothing apriori objectionable in that. The issue is again whether the rational community is the arbiter or whether a prophet who alone can the higher levels appears and takes control. Husserl's phenomenology has often been accused of mysticism because he insisted that experience gives more than sense data. But Husserl does nothing more 'mystical' than what Popper does with his basic statements. For instance, is it hard for you to see that 'your keys on the table' is true or false when you are standing over that table ? It's like reading some number on a screen --- so simple and yet tangled up in the problem of the world being given only perspectively. -

plaque flag

2.7kI haven't fully explored that book, either, but suffice to say for this post, that I think the faculty of rational judgement is indeed 'ethereal' or at least incorporeal - and that this is the original meaning of the 'rational soul' in Aristotle and the Western tradition. It was originally understood as the faculty which discerns the real, albeit in a sense that was subsequently lost to contemporary culture (although arguably preserved in Hegel). That faculty, to grasp meaning or essences, is associated with 'nous' which is the source of rationality. — Quixodian

plaque flag

2.7kI haven't fully explored that book, either, but suffice to say for this post, that I think the faculty of rational judgement is indeed 'ethereal' or at least incorporeal - and that this is the original meaning of the 'rational soul' in Aristotle and the Western tradition. It was originally understood as the faculty which discerns the real, albeit in a sense that was subsequently lost to contemporary culture (although arguably preserved in Hegel). That faculty, to grasp meaning or essences, is associated with 'nous' which is the source of rationality. — Quixodian

I'd say that ideas are relatively incorporeal -- lighter than air. But we only know them as living flesh. While concepts transcend any particular host, we can say nothing about them transcending all such hosts. I mean we cannot speak from experience. We'd be daydreaming, possibly of round squares, for I can't imagine an idea that's not imagined.

But I don't think the idea of the idea was ever lost. Husserl's book Ideas is about (among other things) grasping ideas with intuition. It's a reboot of metaphysics, a new first philosophy, a redo of Kant.

I'd say that the bigger issue is that humans are primarily practical beings. I can't help but think you are frustrated with the status of philosophy in our society. But I think the world has always ignored philosophers when it didn't poison or burn them. So it's got to be its own reward. To me, expecting the world to be more intellectual or spiritual is like expecting the world to stop making babies. I imagine serfs with gum disease in the old days comforted to some degree by a single enforced theology,, and maybe they found the depth in such undeniably rich symbols. But they didn't have autonomy. They didn't wrestle the devil for their victory. How many of us would accept a brainwashing that was certain to make us happy but slavish ? Only the suicidal, I think. -

plaque flag

2.7kBut the salient point here is that such an ability is 'above nature', so to speak. It is 'above' it, in the same sense that the explanans is above the explanadum - it grasps the underlying causes (logos, in the archaic sense) which make general observations, and therefore explanatory principles, possible. So, I'm persuaded that this faculty is linked to the ability to grasp universals (which have generally been rejected by philosophers since the Enlightenment). For Aristotle, this faculty - 'nous' - was distinct from the processing of sensory perception, including the use of imagination and memory, which other animals possess. For him, nous is connected to discussion of how the human mind grasps definitions in a consistent and communicable way (hence universals as a theory of predication) and whether the mind possesses an innate potential to understand them. And in the broader platonist tradition (philosophy generally) there is undoubtedly an heirarchy of being and knowing, but which has been generally occluded by the over-emphasis on empiricism. — Quixodian

plaque flag

2.7kBut the salient point here is that such an ability is 'above nature', so to speak. It is 'above' it, in the same sense that the explanans is above the explanadum - it grasps the underlying causes (logos, in the archaic sense) which make general observations, and therefore explanatory principles, possible. So, I'm persuaded that this faculty is linked to the ability to grasp universals (which have generally been rejected by philosophers since the Enlightenment). For Aristotle, this faculty - 'nous' - was distinct from the processing of sensory perception, including the use of imagination and memory, which other animals possess. For him, nous is connected to discussion of how the human mind grasps definitions in a consistent and communicable way (hence universals as a theory of predication) and whether the mind possesses an innate potential to understand them. And in the broader platonist tradition (philosophy generally) there is undoubtedly an heirarchy of being and knowing, but which has been generally occluded by the over-emphasis on empiricism. — Quixodian

To me this just points to the necessary being of ontology itself. Or, more mundanely, to conceptmongering humanity. How many people deny the existence of meaning ? Of concepts ? Of the human mind's grasp and even creation of concepts ? Almost no one. Though one can of course debate the details.

Given this widespread acknowledgement of conceptuality, which doesn't seem to satisfy you or even be acknowledged by you, it's very hard not to read you as insisting on something mystical or esoteric. Which is fine of course. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe issue is again whether the rational community is the arbiter or whether a prophet who alone can the higher levels appears and takes control. — plaque flag

Wayfarer

26.1kThe issue is again whether the rational community is the arbiter or whether a prophet who alone can the higher levels appears and takes control. — plaque flag

There is a kind of understanding that requires a transformation in the knower, that can only be known first-person. Science also requires a transformation in the sense that you have to be able to grasp the mathematical basis of many of the hypotheses, but this concerns a more immediate mode of understanding. So it might seem 'mystical or esoteric' in the absence of that.

How many people deny the existence of meaning? — plaque flag

Didn't Neitszche portend nihilism as the default condition of modern man? Heidegger had something to say about that too. So, I think the answer is, 'very many', and I think it's directly related to the loss of the vertical dimension, the qualitative dimension.

I can't help but think you are frustrated with the status of philosophy in our society. — plaque flag

I'm certainly frustrated with a lot of what passes as philosophy in our society.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum