-

plaque flag

2.7k

plaque flag

2.7k

FWIW, I embrace perspectivism.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PerspectivismPerspectivism (German: Perspektivismus; also called perspectivalism) is the epistemological principle that perception of and knowledge of something are always bound to the interpretive perspectives of those observing it. While perspectivism does not regard all perspectives and interpretations as being of equal truth or value, it holds that no one has access to an absolute view of the world cut off from perspective.[1] Instead, all such viewing occurs from some point of view which in turn affects how things are perceived. Rather than attempt to determine truth by correspondence to things outside any perspective, perspectivism thus generally seeks to determine truth by comparing and evaluating perspectives among themselves.

As far as we know, the world is only ever given perspectively. I'd just say that it's the world that is given. The nearsighted person sees the same ball as the colorblind person with 20/20 vision. And this is the same ball that the blind person can talk about. The intentional object is part of public discourse. Any denial of this is a performative contradiction. Rational discussion tacitly assumes the conditions of its possibility. The discursive subject is always already among others, sharing in a language that intends objects and concepts in common, in the world. -

Sam26

3.1kWhy don't you start up your own thread. This isn't what I had in mind when I started the thread, although I haven't posted in a while.

Sam26

3.1kWhy don't you start up your own thread. This isn't what I had in mind when I started the thread, although I haven't posted in a while. -

Luke

2.7kIn short, pain is more than the inferential aspect of its concept. — plaque flag

Luke

2.7kIn short, pain is more than the inferential aspect of its concept. — plaque flag

On my reading, at least, Wittgenstein does not deny this “something more”, such as the sensation of pain.

246. … Other people cannot be said to learn of my sensations only from my behaviour — for I cannot be said to learn of them. I have them…

304. “But you will surely admit that there is a difference between pain-behaviour with pain and pain-behaviour without pain.” — Admit it? What greater difference could there be? — “And yet you again and again reach the conclusion that the sensation itself is a Nothing.” -- Not at all. It’s not a Something, but not a Nothing either! The conclusion was only that a Nothing would render the same service as a Something about which nothing could be said. We’ve only rejected the grammar which tends to force itself on us here.

The paradox disappears only if we make a radical break with the idea that language always functions in one way, always serves the same purpose: to convey thoughts — which may be about houses, pains, good and evil, or whatever.

305. “But you surely can’t deny that, for example, in remembering, an inner process takes place.” — What gives the impression that we want to deny anything? When one says, “Still, an inner process does take place here” — one wants to go on: “After all, you see it.” And it is this inner process that one means by the word “remembering”. — The impression that we wanted to deny something arises from our setting our face against the picture of an ‘inner process’. What we deny is that the picture of an inner process gives us the correct idea of the use of the word “remember”. Indeed, we’re saying that this picture, with its ramifications, stands in the way of our seeing the use of the word as it is.

306. Why ever should I deny that there is a mental process? It is only that “There has just taken place in me the mental process of remembering . . .” means nothing more than “I have just remembered . . .” To deny the mental process would mean to deny the remembering; to deny that anyone ever remembers anything.

307. “Aren’t you nevertheless a behaviourist in disguise? Aren’t you nevertheless basically saying that everything except human behaviour is a fiction?” — If I speak of a fiction, then it is of a grammatical fiction. — Philosophical Investigations -

Richard B

569I understand why someone would claim this, and I readily agree that the social aspect is necessary. But I don't think it's exhaustive. Ought we deny our experience of intending an object ? Or intending a state of affairs ? Something like the direct experience of meaning ? I think training is crucial for the linguistic version of this, but once trained we have a certain independence and ability to introspect. — plaque flag

Richard B

569I understand why someone would claim this, and I readily agree that the social aspect is necessary. But I don't think it's exhaustive. Ought we deny our experience of intending an object ? Or intending a state of affairs ? Something like the direct experience of meaning ? I think training is crucial for the linguistic version of this, but once trained we have a certain independence and ability to introspect. — plaque flag

To reiterate what Wittgenstein says in PI 305, "But you surely cannot deny that, for example, in remembering, an inner process takes place." What gives the impression that we want to deny anything? When one says "Still, an inner processes take place here"-one wants to go on: "After all, you see it." And it is this inner process that one means by the word "remembering".-The impression that we wanted to deny something arises from setting our faces against the picture of the 'inner process'. What we deny is that the picture of the inner process gives us the correct idea of the use of the word "to remember".

In terms of "introspection", the idea of "introspection" is shown when we share are ideas with other language users, develop ideas with argument, listen to clarifying questions, see if others can apply our ideas, act on them, and even expand on them. What give "introspection" meanings is not what lies hidden within the self, but what is expressed and understood between others. -

plaque flag

2.7k

plaque flag

2.7k

Thanks for the quote ! I didn't mean to imply that W denied it. Just that a stereoscopic view makes sense.

If you want to dig into this, I started a thread on it.

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/14582/sensational-conceptuality -

plaque flag

2.7kWhat give "introspection" meanings is not what lies hidden within the self, but what is expressed and understood between others. — Richard B

plaque flag

2.7kWhat give "introspection" meanings is not what lies hidden within the self, but what is expressed and understood between others. — Richard B

I claim it's both, and I'm happy to debate the point in a friendly spirit. I invite you to join this thread:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/14582/sensational-conceptuality

I don't want to mess up anyone's blog. -

Luke

2.7kIf you want to dig into this, I started a thread on it. — plaque flag

Luke

2.7kIf you want to dig into this, I started a thread on it. — plaque flag

Thanks, I did see it earlier and was meaning to respond, but didn't want to interrupt your discussion with @Joshs and his view of the radical inconstancy of meaning.

However, I'm not sure whether there is much left to say if W is correct in saying that the private sensation is "not a Nothing", but "a Something about which nothing could be said." -

plaque flag

2.7kHowever, I'm not sure whether there is much left to say if W is correct in saying that the private sensation is "not a Nothing", but "a Something about which nothing could be said." — Luke

plaque flag

2.7kHowever, I'm not sure whether there is much left to say if W is correct in saying that the private sensation is "not a Nothing", but "a Something about which nothing could be said." — Luke

Excellent quotes again. Did you ever check out Husserl ? Might be relevant to this issue.

but didn't want to interrupt — Luke

Well @Joshs and I have been off topic (we could be debating rationality in a more appropriate thread), so I hope you stop in and help us get on track. -

Luke

2.7kDid you ever check out Husserl ? — plaque flag

Luke

2.7kDid you ever check out Husserl ? — plaque flag

No, I haven't read any.

I hope you stop in and help us get on track. — plaque flag

Thanks. I'll take another look and see if I have anything to add. -

plaque flag

2.7kNo, I haven't read any. — Luke

plaque flag

2.7kNo, I haven't read any. — Luke

If you get curious, Zahavi's brief book is dense with great stuff. There's a pdf to circumvent buyer's remorse. (I like paper, but it's nice to be sure first.) -

Luke

2.7kZahavi's brief book is dense with great stuff. — plaque flag

Luke

2.7kZahavi's brief book is dense with great stuff. — plaque flag

Thanks for the tip, appreciate it. I'll check it out. -

RussellA

2.6kWe learn what “red” is by being expose to red objects and judging similarly. What goes on inside is irrelevant to the meaning of the concept “red”. Private experiences of “blue” and “red”? No. — Richard B

RussellA

2.6kWe learn what “red” is by being expose to red objects and judging similarly. What goes on inside is irrelevant to the meaning of the concept “red”. Private experiences of “blue” and “red”? No. — Richard B

I agree. But I think it is important to distinguish words in inverted colours such as "red" from those not in inverted commas, such as red. Otherwise it will be difficult to distinguish between what exists in language and what exists outside of language, whether in thought or the world.

For example, going back to Davidsons theory of meaning, whereby “‘Schnee ist weiss’ is true if and only if snow is white.”. "Schneee ist weiss" is within the object language, and snow is white is within the metalanguage, such that if and only if snow is white then the proposition "snow is white" is true.

Could it be that I have no experience of what we would call “color” but some other experience of a “private” kind? But what could that be and could it ever be communicated? — Richard B

I agree. When you see a "red" object your private subjective experience may be of the colour blue. But it is impossible for anyone other than yourself to know. But the fact that it is impossible to communicate to another person your private subjective experience, does not mean that you haven't had a private subjective experience.

This idea of “private meaning” is tempting but ultimately vacuous compared to where that idea of “meaning” has its life, among a group of language users talking about a shared reality. — Richard B

If you had no "private meaning", if you never had any private subjective experiences, if you never felt pain, saw a colour, smelt a rose, tasted coffee or heard laughter, then one could say that this would be a vacuous life. -

RussellA

2.6kYou talk of wavelengths a moment ago, and I presume you rely on the public inferential aspect of the concept. But it's hard to imagine how you could have a private sense of wavelengths without being immersed in a culture that uses this meaningful token in inferences (explanations.) — plaque flag

RussellA

2.6kYou talk of wavelengths a moment ago, and I presume you rely on the public inferential aspect of the concept. But it's hard to imagine how you could have a private sense of wavelengths without being immersed in a culture that uses this meaningful token in inferences (explanations.) — plaque flag

True. On the one hand, how can I have the private sense of things by description, such as democracy, the 1969 Moon landing, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Machu Picchu, wavelengths, atoms, Julius Caesar, etc. Such description can only be through language, and language requires being part of a society that uses language.

But on the other hand, I can have the private sense of things by acquaintance, such as feeling pain, smelling a rose, tasting coffee, hearing laughter and seeing a colour. Such acquaintance is independent of language, and doesn't require being part of a social group.

How is it possible to understand a wavelength when I only know it through description as "the distance between successive crests of a wave, especially points in a sound wave or electromagnetic wave."

Any whole that is only known by description can only become understandable if the parts are known by acquaintance.

First, as I already know by acquaintance the following parts - the distance between two things, the crest of a wave, a point and a sound - I can remove them from the description, leaving the unknown terms successive, especially and electromagnetic.

Successive is defined as following one another. Especially is defined as singling out one thing over all others. Electromagnetic is defined as relating electric currents and magnetic fields.

Second, as I already know by acquaintance the following parts - one thing following another, one thing taking prominence over another thing, the pain from touching a cattle electric fence and the movement of a compass needle in a magnetic field - I can remove them from the description.

In such as fashion, a whole only known by description may be reduced to component parts known by acquaintance. This allows me the private sense of wavelength, independent of language, and independent of any language-using society. -

RussellA

2.6kThe nearsighted person sees the same ball as the colorblind person with 20/20 vision. And this is the same ball that the blind person can talk about. — plaque flag

RussellA

2.6kThe nearsighted person sees the same ball as the colorblind person with 20/20 vision. And this is the same ball that the blind person can talk about. — plaque flag

I agree that Mary can talk about the concept of colour, ie "colour is the visual perception based on the electromagnetic spectrum. Though colour is not an inherent property of matter, colour perception is related to an object's light absorption, reflection, emission spectra and interference"

But can Mary talk about what it feels like to perceive colour ? -

Richard B

569When you see a "red" object your private subjective experience may be of the colour blue. — RussellA

Richard B

569When you see a "red" object your private subjective experience may be of the colour blue. — RussellA

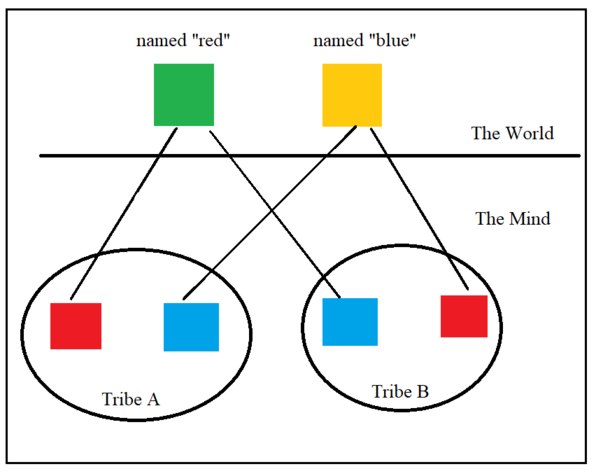

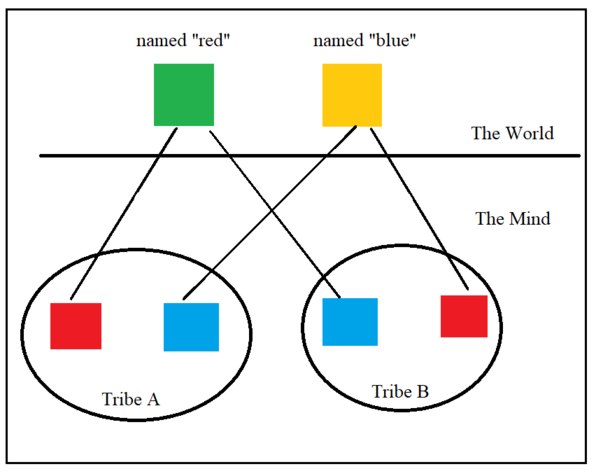

I think this idea is confused based on the very idea on how we learn the language of color and language is general. Please consider this example:

For simplicity sake let us assume we are in a world with just two colors, red and blue. In my tribe, we learned when we see a red object we call it “red” and when we see a blue object, we call it “blue”. One day we travel to an island and we meet another tribe that surprisingly has a very similar language like ours with the exception that when they see a red object they call it “blue” and when they see a blue object they call it “red”. What are we to think in this situation? That they actually see a blue object where we see a red object, or that they simply call a red object “blue” in their language? We can easily ask for the red object by saying “Can you fetch me that blue object” in which they bring me the red object. Would it not be more reasonable to believe our words for “blue” and “red” are “inverted” not how we experience those objects? If this is so, how is this any different when someone says to me, I see that red object but I really see it as “blue.” It is not that we will never know what one actually experiences, but that we are going beyond what the language of color can express. -

Sam26

3.1kHowever, I'm not sure whether there is much left to say if W is correct in saying that the private sensation is "not a Nothing", but "a Something about which nothing could be said." — Luke

Sam26

3.1kHowever, I'm not sure whether there is much left to say if W is correct in saying that the private sensation is "not a Nothing", but "a Something about which nothing could be said." — Luke

This is where I disagree with Wittgenstein. I agree that meaning doesn't reside as a thing in the mind/brain, but I disagree that it's a "something about which nothing can be said." At the very least I can say they are private experiences/sensations, and we often do describe such sensations accurately. Moreover, when talking about, for e.g., the taste of wine, some people who are in the business of describing such tastes, can do it in a way that others can clearly understand. They understand because they too are able to recognize the descriptions. -

RussellA

2.6kFor simplicity sake let us assume we are in a world with just two colors, red and blue. In my tribe, we learned when we see a red object we call it “red” and when we see a blue object, we call it “blue”. One day we travel to an island and we meet another tribe that surprisingly has a very similar language like ours with the exception that when they see a red object they call it “blue” and when they see a blue object they call it “red”. — Richard B

RussellA

2.6kFor simplicity sake let us assume we are in a world with just two colors, red and blue. In my tribe, we learned when we see a red object we call it “red” and when we see a blue object, we call it “blue”. One day we travel to an island and we meet another tribe that surprisingly has a very similar language like ours with the exception that when they see a red object they call it “blue” and when they see a blue object they call it “red”. — Richard B

In the world are two objects. One has been named "red" and the other has been named "blue". No-one knows the true colours of these two objects. However, let them be green and orange for the sake of argument.

For Tribe A to see a red object does not mean that the object they are seeing is red, it just means that they see the colour red when looking at the object named "red",

Similarly, for Tribe A to see a blue object does not mean that the object they are seeing is blue, it just means that they see the colour blue when looking at the object named "blue".

Similarly for Tribe B.

As you say, these two Tribes can still carry on a sensible conversation, because the objects have been named, regardless of any private subjective experiences. This is Wittgenstein's "Beetle in the Box". -

plaque flag

2.7kNo-one knows the true colours of these two objects. — RussellA

plaque flag

2.7kNo-one knows the true colours of these two objects. — RussellA

Overall I agree with your post, but what can true color even mean here ? -

Richard B

569At the very least I can say they are private experiences/sensations, and we often do describe such sensations accurately. — Sam26

Richard B

569At the very least I can say they are private experiences/sensations, and we often do describe such sensations accurately. — Sam26

What could “accurately” mean in such a case of private experiences/sensations. One, no one, in principle, can verify the truth of such an assertion, so why even call it is an assertion. Two, we learn what “accuracy” means by learning the techniques of determining the accuracy of whatever is under examination. Thus, no one can teach another how to determine the accuracy of a private experience/sensation. Lastly, Wittgenstein does not deny one have these experiences but only what can be said, which is not much at all. Just like if someone is in a completely dark room and someone ask “what do you see?” And one replies, “It is dark.” -

Sam26

3.1kWhat could “accurately” mean in such a case of private experiences/sensations. — Richard B

Sam26

3.1kWhat could “accurately” mean in such a case of private experiences/sensations. — Richard B

What accurately means depends on context. So if we give people the same color patches and they describe them using the same words I use, then what more is needed to say they've described the colors accurately, and that they are seeing what I see? For all practical purposed their descriptions are accurate. There's no good reason to think they are seeing different colors. It's a problem without a difference. -

Richard B

569What accurately means depends on context. So if we give people the same color patches and they describe them using the same I words I use, then what more is needed to say they've described the colors accurately, and that they are seeing what I see? For all practical purposed their descriptions are accurate. There's no good reason to think they are seeing different colors. It's a problem without a difference. — Sam26

Richard B

569What accurately means depends on context. So if we give people the same color patches and they describe them using the same I words I use, then what more is needed to say they've described the colors accurately, and that they are seeing what I see? For all practical purposed their descriptions are accurate. There's no good reason to think they are seeing different colors. It's a problem without a difference. — Sam26

As Wittgenstein pointed out in PI 258, there is a problem talking about the accuracy of private sensations, he says towards the end, “But in the present case I have no criterion of correctness. One would like to say: whatever is going to seem right to me is right. And that only means that here we can’t talk about ‘right’.

What goes wrong with some much talk of private sensations is it borrows so much from the language of the public shared reality that words begin to loose their sense, like “right” “accurate”, “judgment”, “remember”, “something” etc… How much do you cut off a tree where it is no longer a tree but a stump? -

Sam26

3.1kAs Wittgenstein pointed out in PI 258, there is a problem talking about the accuracy of private sensations, he says towards the end, “But in the present case I have no criterion of correctness. One would like to say: whatever is going to seem right to me is right. And that only means that here we can’t talk about ‘right’. — Richard B

Sam26

3.1kAs Wittgenstein pointed out in PI 258, there is a problem talking about the accuracy of private sensations, he says towards the end, “But in the present case I have no criterion of correctness. One would like to say: whatever is going to seem right to me is right. And that only means that here we can’t talk about ‘right’. — Richard B

The quote from PI 258 is about the so-called private language argument. I have no problem with the PLA. I think it's clear that rule-following in a private language degenerates into "what seems right is right." However, this is much different from what I was referring to above. My point wasn't about a private language, it was about the public use of words and what we mean by those words (generally speaking). I was addressing the public use of color words, and what it would mean to accurately describe certain colors. The point was that we can and do generally describe colors accurately, so that what I mean by the color blue is generally what we all mean by the color blue. It's not as though we're all confused about what we're seeing or experiencing, unless, for e.g., we talking about very subtle shading or nuanced color differences which may take some training to accurately describe.

What goes wrong with some much talk of private sensations is it borrows so much from the language of the public shared reality that words begin to loose their sense, like “right” “accurate”, “judgment”, “remember”, “something” etc… How much do you cut off a tree where it is no longer a tree but a stump? — Richard B

Yes, these words do borrow (borrow is not a good word for what I'm talking about - words get their meanings from public discourse period - they don't borrow from the public) from public language because if they didn't it would degenerate into purely subjective meanings. Hence, the PLA. I disagree that Wittgenstein would agree that words, such as, right, accurate, judgment, etc lose their sense, if that's what you're indeed saying. It's important when using words like accurate to spell out what qualifies as accurate. In one case of measuring, for e.g., we might say that a measurement within a certain range is accurate, but in another case it may not be. So again how we use words in one language-game might not work in another, but that doesn't mean that the words lose their sense. It just means that sense is dependent upon the language-game you're using at the moment. These language-games are dependent on a wide range of public discourse. -

plaque flag

2.7kWhat could “accurately” mean in such a case of private experiences/sensations. — Richard B

plaque flag

2.7kWhat could “accurately” mean in such a case of private experiences/sensations. — Richard B

I'm not saying this is the final word by any means, but we can't ignore poetry and music.

The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an "objective correlative"; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked.

Notice that it's trivially true that feeling just is not concept. A sentence is not really a painting. We include feelings in our 'inferential ontology' all the time. We can be more or less confident that someone 'gets it.' But our belief about states of affairs of medium size dry goods is also fallible. -

Richard B

569Notice that it's trivially true that feeling just is not concept. — plaque flag

Richard B

569Notice that it's trivially true that feeling just is not concept. — plaque flag

Agreed, feelings are not concepts, but if you want to talk about feelings to your fellow human being there is a lot of set up that needs to take place. We simply do not take a literal picture of what is going on inside and give it to another person and say “see this is how I feel.” We need words associated with particular circumstances; we need a common language to understand those circumstances; we need our fellow human being to react similarly to those circumstances, or at least imagine how they would react, etc… with any luck we get understanding and empathy. -

plaque flag

2.7kYou said:

plaque flag

2.7kYou said:

What could “accurately” mean in such a case of private experiences/sensations. — Richard B

I said:

it's trivially true that feeling just is not concept. A sentence is not really a painting. We include feelings in our 'inferential ontology' all the time. We can be more or less confident that someone 'gets it.' — plaque flag

I also quoted Eliot and said:

The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an "objective correlative"; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked — plaque flag

Then you inform me that:

We need words associated with particular circumstances; we need a common language to understand those circumstances; we need our fellow human being to react similarly to those circumstances — Richard B -

RussellA

2.6kbut what can true color even mean here ? — plaque flag

RussellA

2.6kbut what can true color even mean here ? — plaque flag

Where does colour exist

I agree. It comes down to a matter of opinion.

The Direct Realist would say that as we directly see the world around us, things in the world, such as colours, are perceived immediately rather than inferred on the basis of perceptual evidence.

The Indirect Realist would say that our conscious experience is not directly of the world itself, but is an internal representation of an external world. This external world is real and is the cause of our sensations, but as an effect does not need to be the same as the cause, what we sense is an effect that does not of necessity need to be of the same kind as its cause in the world.

The Direct Realist would therefore say that if we see a red object, then in the world there exists also a red object. The Indirect Realist would say that if we see a red object, all we can say is that our sensation has been caused by something in the world. But as an effect is not of necessity the same as its cause, then the cause in the world must remain unknown. In Kant's terms, a thing in itself.

As an Indirect Realist, I cannot know that colours don't exist in the world but my belief is that they don't.

Wittgenstein's Beetle in the Box supports Indirect Realism

Wittgenstein's support for the Beetle in the Box analogy indicatives his support for Indirect rather than Direct Realism.

Wittgenstein in PI 293 wrote about an unknown beetle:

Suppose everyone had a box with something in it: we call it a "beetle". No one can look into anyone else's box, and everyone says he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle.

If Direct Realism was correct, given a beetle in the external world, I would directly perceive this beetle. Other people would also directly perceive the same beetle. As everyone looking at the beetle would have the same intentional content, everyone would know everyone else's intentional content. Everyone would know that their private perception was the same as everyone else's, contradicting Wittgenstein's private language argument, and contradicting PI para 272 where he wrote that nobody knows another person's sensations:

The essential thing about private experience is really not that each person possesses his own exemplar, but that nobody knows whether other people also have this or something else. The assumption would thus be possible—though unverifiable—that one section of mankind had one sensation of red and another section another.

Wittgenstein's Beetle in the Box is an argument against Direct Realism. -

Luke

2.7khis is where I disagree with Wittgenstein. I agree that meaning doesn't reside as a thing in the mind/brain, but I disagree that it's a "something about which nothing can be said." — Sam26

Luke

2.7khis is where I disagree with Wittgenstein. I agree that meaning doesn't reside as a thing in the mind/brain, but I disagree that it's a "something about which nothing can be said." — Sam26

To be clear, the "something" in question at §304 is not a meaning or anything linguistic, but a private sensation; a feeling. However, I assume this is what you meant.

At the very least I can say they are private experiences/sensations, and we often do describe such sensations accurately. — Sam26

I believe Wittgenstein would say that we do not describe our sensations, but express them. For example:

244. How do words refer to sensations? — There doesn’t seem to be any problem here; don’t we talk about sensations every day, and name them? But how is the connection between the name and the thing named set up? This question is the same as: How does a human being learn the meaning of names of sensations? For example, of the word “pain”. Here is one possibility: words are connected with the primitive, natural, expressions of sensation and used in their place. A child has hurt himself and he cries; then adults talk to him and teach him exclamations and, later, sentences. They teach the child new pain-behaviour.

“So you are saying that the word ‘pain’ really means crying?” — On the contrary: the verbal expression of pain replaces crying, it does not describe it.

245. How can I even attempt to interpose language between the expression of pain and the pain? — Wittgenstein

Moreover, when talking about, for e.g., the taste of wine, some people who are in the business of describing such tastes, can do it in a way that others can clearly understand. They understand because they too are able to recognize the descriptions. — Sam26

If I ask you to fetch me a red object, I will know if you have succeeded in doing so but not because I know how red looks to everyone else. (I cannot even sensibly say that I know how red looks to myself - see §246). What matters is that I can successfully pick out the colour red. Recognising how red looks (to me) will help me to do that, but my personal sensation when seeing a red object does not enter into the meaning of the word. What "red" means is not a description of my personal sensation or how it looks to me in particular. It doesn't matter how the colour looks to me, or whether I truly see red accurately (or whether I see the "real" red). It's almost as if learning to use the word "red" is like putting on a pair of magic glasses that makes you see the same colour as everyone else. It doesn't matter how it looks to me when I'm not wearing my magic glasses, it only matters that how one uses the word "red" corresponds to how other people use the word "red". How it looks to me drops out of consideration as irrelevant. I could be colour-blind or blind and still be able to respond appropriately to a request to fetch a red object. The thing in [one's] box doesn't belong to the language-game at all. All that matters are one's actions/behaviour in response to the word "red".

Similarly, when one describes the tastes of wine, one doesn't describe their private taste sensation, but has learned to use a public language. To say that some food "tastes like chicken", or that a wine tastes "smoky" or "like a blue crayon" (or whatever) is only ever partaking in the public language that magically filters out everyone's individual private sensations. Again, recognising the private sensation will help one to use the language appropriately, but language does not describe one person's private sensation. Or you could say that it does, but in a way which filters it (out) to be the same as everyone else's private sensation.

You use the word "red" appropriately when you see this colour and I use the word "red" appropriately when I see this colour. But, that this colour might appear differently to each of us makes no difference to knowing how to use the word appropriately.

Perhaps my view departs from Wittgenstein's here, too. I'm unsure. -

Richard B

569Again, recognising the private sensation will help one to use the language appropriately, but language does not describe one person's private sensation. — Luke

Richard B

569Again, recognising the private sensation will help one to use the language appropriately, but language does not describe one person's private sensation. — Luke

I think Wittgenstein would say that recognizing a private sensation does not assist in using a word appropriately. Think of PI 265, the train time-table example. He might say using language correctly shows we recognize the private sensation (or maybe ….we experience the private sensation). -

Richard B

569another.

Richard B

569another.

Wittgenstein's Beetle in the Box is an argument against Direct Realism. — RussellA

The Beetle in the Box is not to put forward a philosophical theory or to show support for indirect realism theory but to show that the model of “object and designation” is irrelevant to the meaning of the terms expressed in the language game of pain.

In fact he does not even support indirect realism, consider PI 304, “The conclusion was only that nothing would serve just as well as a something about which nothing could be said.”

An indirect realist would not say this. They would say that there are “somethings” and these somethings are private sensations and we have much to say.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum