-

Mikie

7.3k

Mikie

7.3k

So too ignorant to understand. Got it.

whether these emissions are actually a problem. — Agree to Disagree

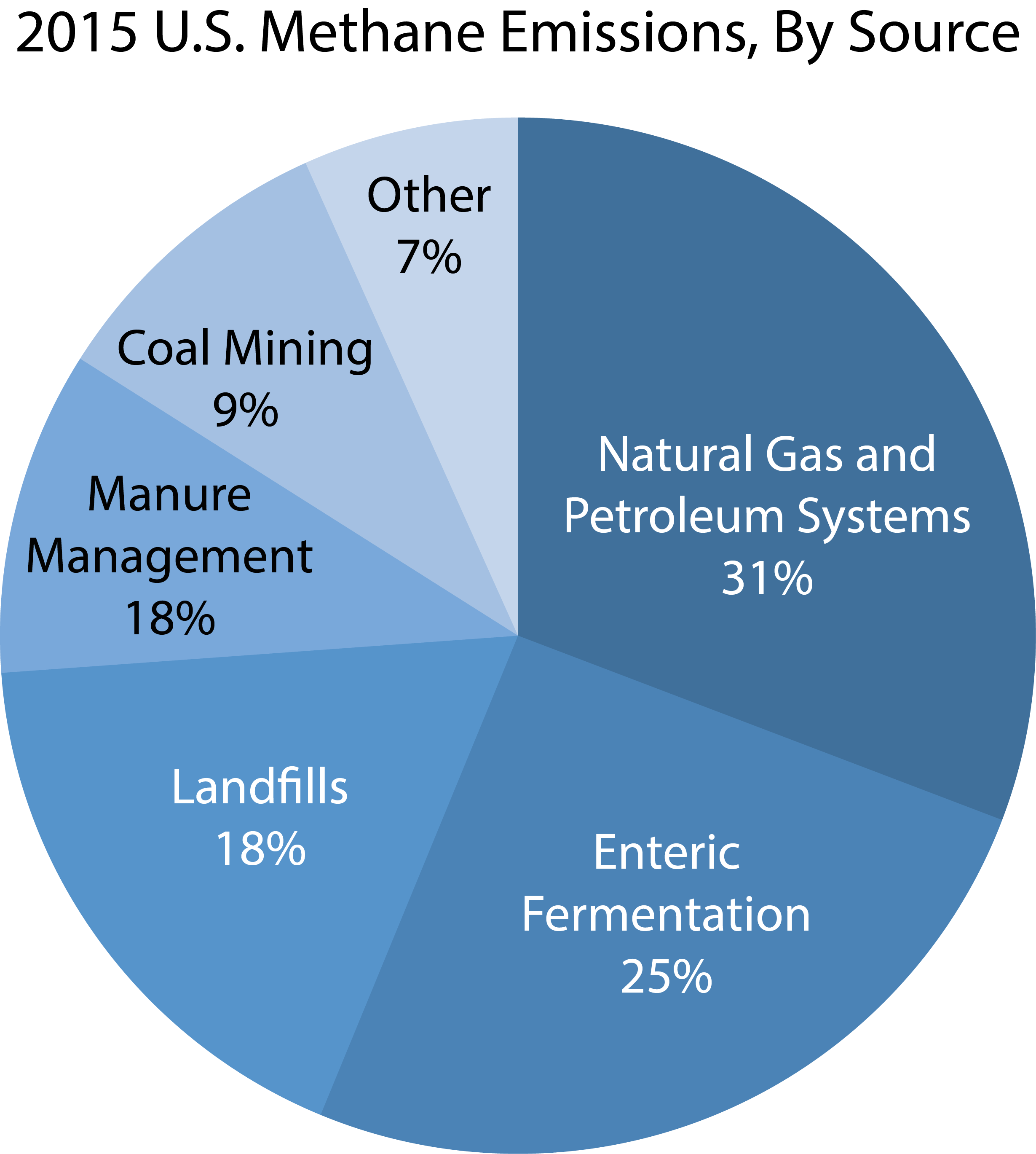

It does not address the very real problem of emissions from livestock, which is on the order of roughly 15%.

None of your sources once addresses land change, and make the ludicrous assumption that “if” we keep the numbers the same, eventually things would stabilize. Yeah, no shit. Since that isn’t close to reality, why you choose to harp on it is pretty telling.

How amazing it must be pretending that there’s no problem, and further pretending you know why — because you googled “biogenic carbon cycle.” Truly embarrassing. But keep trying…all of these climate denial tropes are a good demonstration of how stupid that position is. -

Agree-to-Disagree

674... and make the ludicrous assumption that “if” we keep the numbers the same, eventually things would stabilize. Yeah, no shit. Since that isn’t close to reality, why you choose to harp on it is pretty telling. — Mikie

Agree-to-Disagree

674... and make the ludicrous assumption that “if” we keep the numbers the same, eventually things would stabilize. Yeah, no shit. Since that isn’t close to reality, why you choose to harp on it is pretty telling. — Mikie

You don't seem to realize that if the number of cows has already been approximately constant for the last 12 years then the situation is already stabilized. The current number of cows won't cause any additional global warming. The total methane level from cows is already constant in the atmosphere. -

frank

18.9kIt talks about livestock emissions and whether these emissions are actually a problem. — Agree to Disagree

frank

18.9kIt talks about livestock emissions and whether these emissions are actually a problem. — Agree to Disagree

If you don't think we can do anything about climate change, it doesn't really matter if cattle farming is net-zero, does it? -

Mikie

7.3k

Mikie

7.3k

We’re not only talking about cows— despite your obsession with them.

Anyway, here’s some references if you want to learn:

https://thebreakthrough.org/issues/food-agriculture-environment/livestock-dont-contribute-14-5-of-global-greenhouse-gas-emissions#:~:text=In%20short%2C%20livestock%20production%20appears,land%2C%20or%20land%2Duse%20change

In short, livestock production appears to contribute about 11%–17% of global greenhouse gas emissions, when using the most recent GWP-100 values, though there remains great uncertainty in much of the underlying data such as methane emissions from enteric fermentation, CO2 emissions from grazing land, or land-use change caused by animal agriculture.

https://www.wri.org/insights/6-pressing-questions-about-beef-and-climate-change-answered

1. How does beef production cause greenhouse gas emissions?

The short answer: Through the agricultural production process and through land-use change.

The longer explanation: Cows and other ruminant animals (like goats and sheep) emit methane, a potent greenhouse gas, as they digest grasses and plants. This process is called “enteric fermentation,” and it’s the origin of cows’ burps. Methane is also emitted from manure. Additionally, nitrous oxide, another powerful greenhouse gas, is emitted from ruminant wastes on pastures and chemical fertilizers used on crops produced for cattle feed.

More indirectly but also importantly, rising beef production requires increasing quantities of land. New pastureland is often created by cutting down trees, which releases carbon dioxide stored in forests.

In 2017, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated that total annual emissions from beef production, including agricultural production emissions plus land-use change, were about 3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2010. That means emissions from beef production in 2010 were roughly on par with those of India, and about 7% of total global greenhouse gas emissions that year. Because FAO only modestly accounted for land-use-change emissions, this is a conservative estimate.

Global demand for beef and other ruminant meats continues to grow, rising by 25% between 2000 and 2019. During the first two decades of this century, pastureland expansion was the leading direct driver of deforestation. Continued demand growth will put pressure on forests, biodiversity and the climate. Even after accounting for improvements in beef production efficiency, pastureland could expand by an estimated 400 million hectares, an area of land larger than the size of India, between 2010 and 2050. The resulting deforestation could increase global emissions enough to put the global goal of limiting temperature rise to 1.5-2 degrees C (2.7-3.6 degrees F) out of reach.

At COP26, global leaders pledged to reduce methane emissions by 30% and end deforestation by 2030. Addressing beef-related emissions could help countries meet both pledges.

3. Why are some people saying beef production is only a small contributor to emissions?

The short answer: Such estimates commonly leave out land-use impacts, such as cutting down forests to establish new pastureland.

The longer explanation: There are a lot of statistics out there that account for emissions from beef production, but not from associated land-use change. For example, here are three common U.S. estimates:

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimated total U.S. agricultural emissions in 2019 at only 10% of total U.S. emissions.

A 2019 study in Agricultural Systems estimated emissions from beef production at only 3% of total U.S. emissions.

A 2017 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences estimated that removing all animals from U.S. agriculture would reduce U.S. emissions by only 3%.

While all of these estimates account for emissions from U.S. agricultural production, they leave out a crucial element: emissions associated with devoting land to agriculture. An acre of land devoted to food production is often an acre that could store far more carbon if allowed to grow forest or its native vegetation. And when considering the emissions associated with domestic beef production, estimates must look beyond national borders, especially since global beef demand is on the rise.

Because food is a global commodity, what is consumed in one country can drive land use impacts and emissions in another. An increase in U.S. beef consumption, for example, can result in deforestation to make way for pastureland in Latin America. Conversely, a decrease in U.S. beef consumption can avoid deforestation and land-use-change emissions abroad. As another example, U.S. beef exports to China have been growing rapidly since 2020.

When the land-use effects of beef production are accounted for, the GHG impacts associated with the average American-style diet actually comes close to per capita U.S. energy-related emissions. A related analysis found that the average European’s diet-related emissions, when accounting for land-use impacts, are similar to the per capita emissions typically assigned to each European’s consumption of all goods and services, including energy.

https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-05/global_emissions_sector_2015.png -

EricH

660I gave you 2 other sources which are NOT meat companies. What don't you like about these 2 sources?

EricH

660I gave you 2 other sources which are NOT meat companies. What don't you like about these 2 sources?

This one is The University of California, Davis

https://clear.ucdavis.edu/explainers/biogenic-carbon-cycle-and-cattle — Agree to Disagree

It appears that you have misinterpreted this source. The full impact of this article is that reducing methane is the best way to reduce global warming - because reducing methane has a more immediate impact on the environment than reducing CO2. Go to minute 4:00 of the video where the narrator talks about steps that California is taking to reduce methane emissions.

If there is still any doubt in your mind, here is another article from the same source you cited:

https://clear.ucdavis.edu/news/new-report-california-pioneering-pathway-significant-dairy-methane-reduction -

jorndoe

4.2kIncreasing wildfires are likely partially + cumulatively caused by climate change, and are bound to have a climatic effect in turn.

jorndoe

4.2kIncreasing wildfires are likely partially + cumulatively caused by climate change, and are bound to have a climatic effect in turn.

As the wildfires in Canada continue to shroud much of the midwest in a thick haze of smoke, New Yorkers are preparing yet again for the smoke to make its way further east. — The Guardian · Jun 27, 2023Based on data from the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre, there are 480 active fires in Canada: 252 are out of control, 77 are being held in place, and 151 are under control. — GPS World · Jun 28, 2023Smoke from Canadian wildfires has reached Europe — Euronews · Jun 28, 2023Data also shows that Canada has experienced 11,598 fires during the first seven months of this year alone. This is a 705% increase compared to fires detected over the same period of the previous six years. Canada is currently battling the country’s worst wildfire season on record, with more than 10 million ha of land burned, which is said to increase in the coming weeks. — GPS World · Aug 4, 2023

Lots of :fire: this year. Will this become a new norm of sorts?

Copernicus EFFIS (interactive)

NASA FIRMS (interactive) -

Pantagruel

3.6kthe situation is already stabilized. The current number of cows won't cause any additional global warming. The total methane level from cows is already constant in the atmosphere. — Agree to Disagree

Pantagruel

3.6kthe situation is already stabilized. The current number of cows won't cause any additional global warming. The total methane level from cows is already constant in the atmosphere. — Agree to Disagree

There isn't a shred of logic in these statements. Even if it were true that output was stabile, that doesn't imply that the situation to which the output is a contributing factor is stabile. And the fact that the current number of cows won't cause "any additional" global warming just means that the ongoing amount of their ecological impact isn't decreasing. Which is the point. -

frank

18.9kThere isn't a shred of logic in these statements. Even if it were true that output was stabile, that doesn't imply that the situation to which the output is a contributing factor is stabile. And the fact that the current number of cows won't cause "any additional" global warming just means that the ongoing amount of their ecological impact isn't decreasing. Which is the point. — Pantagruel

frank

18.9kThere isn't a shred of logic in these statements. Even if it were true that output was stabile, that doesn't imply that the situation to which the output is a contributing factor is stabile. And the fact that the current number of cows won't cause "any additional" global warming just means that the ongoing amount of their ecological impact isn't decreasing. Which is the point. — Pantagruel

He's just saying that cattle farming is net-zero wrt greenhouse gas emissions. That's what we want all human operations to be. It's ok to produce greenhouse gases as long as your emissions are being scrubbed somehow.

Whether it's really the case that cattle farming is net-zero, I have no idea. -

Pantagruel

3.6kEven if that were true, there is a certain "environmental load" to maintaining any greenhouse-gas involved process. If scale of cattle-farming were reduced, the "environmental load" would also be reduced. Which is part of the goal, I think.

Pantagruel

3.6kEven if that were true, there is a certain "environmental load" to maintaining any greenhouse-gas involved process. If scale of cattle-farming were reduced, the "environmental load" would also be reduced. Which is part of the goal, I think. -

frank

18.9kEven if that were true, there is a certain "environmental load" to maintaining any greenhouse-gas involved process. If scale of cattle-farming were reduced, the "environmental load" would also be reduced. Which is part of the goal, I think. — Pantagruel

frank

18.9kEven if that were true, there is a certain "environmental load" to maintaining any greenhouse-gas involved process. If scale of cattle-farming were reduced, the "environmental load" would also be reduced. Which is part of the goal, I think. — Pantagruel

What kind of load? -

BC

14.2kHave you ever been through West Virginia and seen the huge bands of coal in the cliffs beside the highway? Awesome. — frank

BC

14.2kHave you ever been through West Virginia and seen the huge bands of coal in the cliffs beside the highway? Awesome. — frank

No, but that would be highly interesting.

I was at Cumberland Falls in Kentucky a few years ago and picked up some pieces of coal that had washed down from up stream. The pieces were rounded and smoothed; quite nice. I've never thought of coal as a rock, either. When I was a child, we heated the house with a coal space heater. Usually the coal was briquettes, but sometimes it was chunk coal, some of the chunks being the size of a small watermelon or cantaloupe.

I suppose, upon your first naive encounter with unprocessed coal one could think of it as a rock. It is rock-like in hardness and weight, but it has very unrocklike features. For instance, if you apply a small torch flame to the surface of unprocessed coal, little jets of gas will ignite; if you apply more heat, the surface will chip off. Apply enough heat and it burns. Rocks don't do that.

The residue of burnt coal is more clearly a mineral. Clinkers formed in the bottom of the stove. They were fairly hard and brittle -- but not a solid mass -- lots of irregular shapes and holes. Coal ash is reddish grey-brown and relatively light in weight. The ash will become toxic when water leaches out the various chemicals native to coal and created by combustion. -

Pantagruel

3.6kAny process that involves methane, for example, involves the transport of that methane throughout a cycle, portions of which are stored for durations in the environment. Carbon is stored and flows in such a cycle. And nitrogen. Viewing cattle as an abstract point of methane data is unrealistic. Short-term, a cow is a very-high-net methane producer. Reduce the number of cows and you must reduce the net-methane load in the environment.

Pantagruel

3.6kAny process that involves methane, for example, involves the transport of that methane throughout a cycle, portions of which are stored for durations in the environment. Carbon is stored and flows in such a cycle. And nitrogen. Viewing cattle as an abstract point of methane data is unrealistic. Short-term, a cow is a very-high-net methane producer. Reduce the number of cows and you must reduce the net-methane load in the environment. -

BC

14.2kMeat produced through rotating grassland grazing (without a finishing program of grain feed) is quite possibly sustainable. I generally buy grass-fed ground beef. What isn't sustainable and good for the earth are very high levels of beef production.

BC

14.2kMeat produced through rotating grassland grazing (without a finishing program of grain feed) is quite possibly sustainable. I generally buy grass-fed ground beef. What isn't sustainable and good for the earth are very high levels of beef production.

Most of the beef sold is NOT grass-fed -- it's grass for-a-while then grain-finished. I discussed the increased CO2 load from grain production above.

True enough, methane is much shorter-lived than CO2--12 years, +/- as you said. The problem is that we are loading the atmosphere with more and more methane -- much of it from natural gas and oil production. The increased load of methane is the problem -- not that it takes a long time to break down, like CO2. Belching cattle are one source. There are a lot of cattle on the planet, about a billion.

There are also about a billion automobiles in the world, which produce various noxious chemicals and which we can't eat.

Plants do take up CO2, of course. Unfortunately, we are reducing the planets best carbon sinks -- rain forests. Grass lands can absorb CO2 also, as can crop land. Both grazing and crop production can be managed to maximize CO2 uptake. This requires minimum tillage, and rotating the grazers so that they don't "clear cut" the pasturage. This method of meat production takes more labor and attention than the other method.

We should be planting more trees, and restoring crop and grazing land so that more CO2 could be captured and sequestered in soil.

The information on Good Meats isn't wrong, but quantity matters when it comes to CO2 and methane, -

frank

18.9kAny process that involves methane, for example, involves the transport of that methane throughout a cycle, portions of which are stored for durations in the environment. Carbon is stored and flows in such a cycle. And nitrogen. Viewing cattle as an abstract point of methane data is unrealistic. Short-term, a cow is a very-high-net methane producer. Reduce the number of cows and you must reduce the net-methane load in the environment. — Pantagruel

frank

18.9kAny process that involves methane, for example, involves the transport of that methane throughout a cycle, portions of which are stored for durations in the environment. Carbon is stored and flows in such a cycle. And nitrogen. Viewing cattle as an abstract point of methane data is unrealistic. Short-term, a cow is a very-high-net methane producer. Reduce the number of cows and you must reduce the net-methane load in the environment. — Pantagruel

But it's the nature of a cycle that as methane is emitted today, the components of yesterday's emissions are simultaneously being taken up by plants. This is the argument, anyway.

I used to do aquariums, so I'm somewhat tuned into cycling and bio load on a closed system. I presently have an immortal fish with whom I have a troubled relationship. I want her to die so I can close down my last aquarium, but she's now about 4 times the age her species is supposed to live. I think of letting the bio load rise until the pH is incompatible with life, but I can't do it!

Sorry for the extraneous details. -

Pantagruel

3.6kBut it's the nature of a cycle that as methane is emitted today, the components of yesterday's emissions are simultaneously being taken up by plants. This is the argument, anyway. — frank

Pantagruel

3.6kBut it's the nature of a cycle that as methane is emitted today, the components of yesterday's emissions are simultaneously being taken up by plants. This is the argument, anyway. — frank

Right. And if all methane-producing elements in the environment were somehow eliminated, the methane levels would drop. Whether, in the grand scheme of things, a cow is "methane-neutral" is a pretty hard to say. But biologically (vs systemically) speaking, cows are "methane generators". If all cattle were gone, methane levels would decrease. -

BC

14.2k

BC

14.2k

8 billion+ people, a billion cattle, a billion cars, a petroleum-dependent world economy, cement production (cooking limestone to make lime), metal production, airlines, a mindless garbage problem -- it is ALL the problem.

The "cure" may be as unpalatable as the "disease".

Agree to Disagree is not being substantially more recalcitrant than a billion car owners that do not want to give up their private vehicles, or give up good roads to drive on, or a few billion carnivores who do not want to replace meat with beans and greens.

Our ways of living are unsustainable, and we are in trouble and heading for worse. Sure, some individuals don't see the problem, but entire governments can't seem to actually do very much either--never mind the corporate sector. Either very few or no G20 governments have managed to act effectively on carbon dioxide/methane gas reduction. Sure, spotty progress is being made here and there, but critical decades have passed where nothing got done. -

BC

14.2kHow did you start the heater? Did you use lighter fluid? — frank

BC

14.2kHow did you start the heater? Did you use lighter fluid? — frank

No, we used a small wood fire to get the coal going. During the winter, the fire was maintained by the regular addition of more coal (done by hand). At night, the coal would burn down and almost nothing left in the morning, so around 6:00 more coal had to be added.

A lot of people heated with coal. Until the late 60s the only alternative in the upper midwest was oil. Unless they were buying gravel coal (ground up to the size of gravel that could be loaded into the furnace by an auger) they had to add the coal with a shovel or a bucket. You opened the stove's door and threw the coal in.

The other source of heat for the house was a large cast iron wood burning cooking stove that had been converted to oil--kerosene. The stove was supplied from a 5 gallon tank that had to be refilled once a day from a bigger tank in the barn. Quite a few times a day, the stove's tank would make a "glug-glug-glug" sound as air filled the emptying space in the tank. It was especially noticeable in the night's quiet. This stove also was on all winter. (Our house was an old, uninsulated leaky frame building). -

unenlightened

10kWith stable livestock numbers the total amount of methane in the atmosphere from cows remains at the same level. This is because the amount of methane added to the atmosphere each year equals the amount of methane removed from the atmosphere each year (by breaking down into carbon dioxide (CO2) and water). — Agree to Disagree

unenlightened

10kWith stable livestock numbers the total amount of methane in the atmosphere from cows remains at the same level. This is because the amount of methane added to the atmosphere each year equals the amount of methane removed from the atmosphere each year (by breaking down into carbon dioxide (CO2) and water). — Agree to Disagree

This is true. But what is not mentioned is that the more cows there are, the higher the stable amount of methane in the atmosphere is. And the amount that it increases as we increase meat production has to be added to other sources of methane from leaky pipes, oil wells, melting permafrost, etc.

So it's not "the answer" because no one thing is the answer, but eating less red meat in particular is a very good way to buy more time to take other measures if enough people start doing it. In the UK, this is happening to the extent that vegetarian and vegan options have become ubiquitous in supermarkets, restaurants and fast food outlets. And it helps a bit. It also helps to reduce the pressure on the rainforest of the Amazon basin, for example, which is being cut down and burned to make room for more cattle and more soya and maize cattle feed. I'm not an expert on the Australian ecosystem, but the introduction of non-native species has not been without problems.

https://wwf.org.au/what-we-do/food/beef/#No other rural industry impacts more of Australia than our beef industry. More than 63,000 farming businesses are producing beef from 43% of the country's landmass. We are also the world's second largest beef exporter, which injects an estimated $8.4 billion into the Australian economy.

More than any other livestock industry, the beef industry relies on healthy natural ecosystems. Fodder and clean water are essential. But cattle production is costly to the environment. Clearing native vegetation for pasture has sacrificed wildlife habitat, and poor grazing practices have seen excess sediments enter waterways and damage places like the . Cattle are also significant greenhouse gas producers, which contributes to climate change. — WWF -

frank

18.9kIf all cattle were gone, methane levels would decrease. — Pantagruel

frank

18.9kIf all cattle were gone, methane levels would decrease. — Pantagruel

If cattle farming were truly net-zero, this wouldn't be true. As you say, we don't know if it is. A pretty complex analysis would have to be brought to bear. -

Pantagruel

3.6kIf cattle farming were truly net-zero, this wouldn't be true. — frank

Pantagruel

3.6kIf cattle farming were truly net-zero, this wouldn't be true. — frank

Yes, it would be true. This is why:

This is true. But what is not mentioned is that the more cows there are, the higher the stable amount of methane in the atmosphere is — unenlightened

This is exactly what I have been describing. Livestock population levels correlate with a certain systemic level of methane.

The fact of the matter is, we should be making whatever reductions even remotely make sense and actively searching for new possibilities to do so. We have been quite content to radically disturb the biosphere haphazardly in aid of profit, we should be courageous enough to do so systematically in aid of human well being. -

frank

18.9kIf cattle farming were truly net-zero, this wouldn't be true.

frank

18.9kIf cattle farming were truly net-zero, this wouldn't be true.

— frank

Yes, it would be true. This is why:

This is true. But what is not mentioned is that the more cows there are, the higher the stable amount of methane in the atmosphere is

— unenlightened — Pantagruel

I'm not seeing this. Let's say we start from today. There's an average of 1.7 ppm of methane in the atmosphere. This average covers seasonal variation. Now we'll add a cattle farm in Mexico, and it's truly net zero, which means that after 12 years, its output is entirely absorbed by its input.

Why would there be a net increase in methane?

he fact of the matter is, we should be making whatever reductions even remotely make sense and actively searching for new possibilities to do so. We have been quite content to radically disturb the biosphere haphazardly in aid of profit, we should be courageous enough to do so systematically in aid of human well being. — Pantagruel

And I repeated this same sentiment earlier in the thread. The thing is, it really doesn't relate to the argument Agree-to-Disagree made. My point is just this: his assertion is not illogical. I would need more than a vague principle to accept that cattle farming is net-zero. But if he's correct that it is, then he's right that it's not a contribution to global warming. -

Pantagruel

3.6kI'm not seeing this. Let's say we start from today. There's an average of 1.7 ppm of methane in the atmosphere. This average covers seasonal variation. Now we'll add a cattle farm in Mexico, and it's truly net zero, which means that after 12 years, its output is entirely absorbed by its input. — frank

Pantagruel

3.6kI'm not seeing this. Let's say we start from today. There's an average of 1.7 ppm of methane in the atmosphere. This average covers seasonal variation. Now we'll add a cattle farm in Mexico, and it's truly net zero, which means that after 12 years, its output is entirely absorbed by its input. — frank

You are not grasping that this is a system and there is a definable quantity of methane within the entire system that correlates with a specific population level of cattle. Ergo any decrease in the population of the cattle is simultaneously a decrease in the associated methane level. It is irrelevant over what period of time the cattle achieve a net-zero methane balance. -

unenlightened

10kcattle farming is net-zero. — frank

unenlightened

10kcattle farming is net-zero. — frank

It can be net zero in terms of carbon, but if you double the number of animals, you double the methane released. in 12 years time all the first year's methane will have degraded through lightening and radiation aided oxidation, but meanwhile the overall amount of methane of bovine origin will have doubled and that will be the new 'stable amount' in the atmosphere.

But google is your friend.

https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/oil-gas-and-coal/methane-emissions_en#:~:text=Methane%20is%20the%20second%20most,on%20a%2020%2Dyear%20timescale.Methane is the second most important greenhouse gas contributor to climate change following carbon dioxide. On a 100-year timescale, methane has 28 times greater global warming potential than carbon dioxide and is 84 times more potent on a 20-year timescale. -

frank

18.9kYou are not grasping that this is a system and there is a definable quantity of methane within the entire system that correlates with a specific population level of cattle. Ergo any decrease in the population of the cattle is simultaneously a decrease in the associated methane level. It is irrelevant over what period of time the cattle achieve a net-zero methane balance. — Pantagruel

frank

18.9kYou are not grasping that this is a system and there is a definable quantity of methane within the entire system that correlates with a specific population level of cattle. Ergo any decrease in the population of the cattle is simultaneously a decrease in the associated methane level. It is irrelevant over what period of time the cattle achieve a net-zero methane balance. — Pantagruel

The cows put out 1 ppm of methane. The plants take up 1 ppm of methane. That's what net-zero means.

I think you're just basically asserting that it isn't possible for a cattle farm to be net-zero.

:up: -

wonderer1

2.4kNow we'll add a cattle farm in Mexico, and it's truly net zero, which means that after 12 years, its output is entirely absorbed by its input. — frank

wonderer1

2.4kNow we'll add a cattle farm in Mexico, and it's truly net zero, which means that after 12 years, its output is entirely absorbed by its input. — frank

What is the proposal for how atmospheric methane is absorbed by the farm? As I understand it, plants don't make use of atmospheric methane as they make use of atmospheric CO2. (Although some species of bacteria metabolize methane.) -

Pantagruel

3.6kThe cows put out 1 ppm of methane. The plants take up 1 ppm of methane. That's what net-zero means. — frank

Pantagruel

3.6kThe cows put out 1 ppm of methane. The plants take up 1 ppm of methane. That's what net-zero means. — frank

Yes, and it also means that there is always a correlative amount of methane hanging about in the system. It doesn't just flow from the butt of the cow into the tissues of the plant. -

frank

18.9kWhat is the proposal for how atmospheric methane is absorbed by the farm? As I understand it, plants don't make use of atmospheric methane as they make use of atmospheric CO2. (Although some species of bacteria metabolize methane.) — wonderer1

frank

18.9kWhat is the proposal for how atmospheric methane is absorbed by the farm? As I understand it, plants don't make use of atmospheric methane as they make use of atmospheric CO2. (Although some species of bacteria metabolize methane.) — wonderer1

Methane oxidizes to CO2 after about 12 years.

The cows put out 1 ppm of methane. The plants take up 1 ppm of methane. That's what net-zero means.

— frank

Yes, and it also means that there is always a correlative amount of methane hanging about in the system. It doesn't just flow from the mouth of the cow into the tissues of the plant. — Pantagruel

Yes. The emissions won't be absorbed for about 12 years, but cattle farms don't last forever. After Juan retires and closes down the farm the plants still absorb the methane for about 12 years. In the end, if the farm was truly net zero, it did not contribute to global warming. -

Agree-to-Disagree

674If you don't think we can do anything about climate change, it doesn't really matter if cattle farming is net-zero, does it? — frank

Agree-to-Disagree

674If you don't think we can do anything about climate change, it doesn't really matter if cattle farming is net-zero, does it? — frank

The big problem is that economies and countries and people (farmers, etc) who depend on cows (beef, dairy, etc) are being punished for no good reason. Economies and counties and people are being damaged financially. Countries that are damaged financially have less money to fight fossil fuels, and are wasting resources that could be used to fight fossil fuels.

I may have given people the impression that I thought that there is nothing that we can do about global warming. I think that this is probably true short-term. Part of the reason for this is that people don't understand the real situation and are concentrating on the wrong solutions. They are rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic, as the Titanic slowly sinks.

I think that there is something that we might be able to do about global warming long-term. If we concentrate on the right solutions. Even then, it will be difficult and take a long time. I favor a slow move away from fossil fuels. But not so fast that it creates big problems.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum