-

plaque flag

2.7kFor the convenience of others, I provide some crucial quotes from J. S. Mill.

plaque flag

2.7kFor the convenience of others, I provide some crucial quotes from J. S. Mill.

https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/mill-the-collected-works-of-john-stuart-mill-volume-ix-william-hamiltons-philosophyI see a piece of white paper on a table. I go into another room. But, though I have ceased to see it, I am persuaded that the paper is still there. I no longer have the sensations which it gave me; but I believe that when I again place myself in the circumstances in which I had those sensations, that is, when I go again into the room, I shall again have them; and further, that there has been no intervening moment at which this would not have been the case. Owing to this property of my mind, my conception of the world at any given instant consists, in only a small proportion, of present sensations. Of these I may at the time have none at all, and they are in any case a most insignificant portion of the whole which I apprehend.The conception I form of the world existing at any moment, comprises, along with the sensations I am feeling, a countless variety of possibilities of sensation: namely, the whole of those which past observation tells me that I could, under any supposable circumstances, experience at this moment, together with an indefinite and illimitable multitude of others which though I do not know that I could, yet it is possible that I might, experience in circumstances not known to me. These various possibilities are the important thing to me in the world. My present sensations are generally of little importance, and are moreover fugitive: the possibilities, on the contrary, are permanent, which is the character that mainly distinguishes our idea of Substance or Matter from our notion of sensation. These possibilities, which are conditional certainties, need a special name to distinguish them from mere vague possibilities, which experience gives no warrant for reckoning upon.

It's a nice thing to point out. At any given moment we have only a small piece of the world before us. But this tiny piece is fringed or enclosed within a vast sense of the possible. I could walk downstairs and make some coffee (tho really I shouldn't). I could google X and go down that rabbit hole.

Some might say that possibility is a mere illusion, but I'd just say that 'actuality' is a favored kind of being, typically for practical reasons. I can't spend the idea of one hundred dollars, or the one hundred dollars that only might be there. -

plaque flag

2.7k

plaque flag

2.7k

https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/mill-the-collected-works-of-john-stuart-mill-volume-ix-william-hamiltons-philosophyThe sensations, though the original foundation of the whole, come to be looked upon as a sort of accident depending on us, and the possibilities as much more real than the actual sensations, nay, as the very realities of which these are only the representations, appearances, or effects. When this state of mind has been arrived at, then, and from that time forward, we are never conscious of a present sensation without instantaneously referring it to some one of the groups of possibilities into which a sensation of that particular description enters; and if we do not yet know to what group to refer it, we at least feel an irresistible conviction that it must belong to some group or other; i.e. that its presence proves the existence, here and now, of a great number and variety of possibilities of sensation, without which it would not have been. The whole set of sensations as possible, form a permanent background to any one or more of them that are, at a given moment, actual; and the possibilities are conceived as standing to the actual sensations in the relation of a cause to its effects, or of canvas to the figures painted on it, or of a root to the trunk, leaves, and flowers, or of a substratum to that which is spread over it, or, in transcendental language, of Matter to Form.

When this point has been reached, the Permanent Possibilities in question have assumed such unlikeness of aspect, and such difference of apparent relation to us, from any sensations, that it would be contrary to all we know of the constitution of human nature that they should not be conceived as, and believed to be, at least as different from sensations as sensations are from one another. Their groundwork in sensation is forgotten, and they are supposed to be something intrinsically distinct from it.

We can withdraw ourselves from any of our (external) sensations, or we can be withdrawn from them by some other agency. But though the sensations cease, the possibilities remain in existence; they are independent of our will, our presence, and everything which belongs to us. We find, too, that they belong as much to other human or sentient beings as to ourselves. We find other people grounding their expectations and conduct upon the same permanent possibilities on which we ground ours. But we do not find them experiencing the same actual sensations. Other people do not have our sensations exactly when and as we have them: but they have our possibilities of sensation; whatever indicates a present possibility of sensations to ourselves, indicates a present possibility of similar sensations to them, except so far as their organs of sensation may vary from the type of ours. This puts the final seal to our conception of the groups of possibilities as the fundamental reality in Nature. The permanent possibilities are common to us and to our fellow-creatures; the actual sensations are not. That which other people become aware of when, and on the same grounds, as I do, seems more real to me than that which they do not know of unless I tell them. The world of Possible Sensations succeeding one another according to laws, is as much in other beings as it is in me; it has therefore an existence outside me; it is an External World. — Mill

I think there are two views that tend to be conflated that should be distinguished.

The first view features every ego in a sort of bubble of dreamstuff, some of which may [merely] represent a outer, 'real' world. This is what I find in varieties of indirect realism. Appearance is given with a kind of incorrigible, absolute intimacy. But one can never be sure whether it refers beyond itself.

The second view is perspectivism (ontological cubism, neutral monism, etc.) The 'transcendental' ego (the metaphysical and not the empirical subject) is the being of the-world-from-a-perspective. This means that the world is arranged spatially around the flesh associated with that metaphysicalsubject.As Mach would put it, there are decisive and especially prominent functional relationships between the elements constituting this special flesh (including 'inside' its 'mind') and the elements understood to constitute everything else.

https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/mach.htmAs soon as we have perceived that the supposed unities " body " and " ego " are only makeshifts, designed for provisional orientation and for definite practical ends (so that we may take hold of bodies, protect ourselves against pain, and so forth), we find ourselves obliged, in many more advanced scientific investigations, to abandon them as insufficient and inappropriate. The antithesis between ego and world, between sensation (appearance) and thing, then vanishes, and we have simply to deal with the connexion of the elements a b c . . . A B C . . . K L M . . ., of which this antithesis was only a partially appropriate and imperfect expression. This connexion is nothing more or less than the combination of the above-mentioned elements with other similar elements (time and space). Science has simply to accept this connexion, and to get its bearings in it, without at once wanting to explain its existence. — Mach

To me this is a beautiful breakthrough to a kind of phenomenological field of neutral elements, prior to mind and matter that emerge later. We go back to an idealized state-before-differentiation. -

plaque flag

2.7k

plaque flag

2.7k

https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/mill-the-collected-works-of-john-stuart-mill-volume-ix-william-hamiltons-philosophyMatter, then, may be defined, a Permanent Possibility of Sensation. If I am asked, whether I believe in matter, I ask whether the questioner accepts this definition of it. If he does, I believe in matter: and so do all Berkeleians. In any other sense than this, I do not. But I affirm with confidence, that this conception of Matter includes the whole meaning attached to it by the common world, apart from philosophical, and sometimes from theological, theories. The reliance of mankind on the real existence of visible and tangible objects, means reliance on the reality and permanence of Possibilities of visual and tactual sensations, when no such sensations are actually experienced. We are warranted in believing that this is the meaning of Matter in the minds of many of its most esteemed metaphysical champions, though they themselves would not admit as much: for example, of Reid, Stewart, and Brown. For these three philosophers alleged that all mankind, including Berkeley and Hume, really believed in Matter, inasmuch as unless they did, they would not have turned aside to save themselves from running against a post. Now all which this manœuvre really proved is, that they believed in Permanent Possibilities of Sensation. We have therefore the unintentional sanction of these three eminent defenders of the existence of matter, for affirming, that to believe in Permanent Possibilities of Sensation is believing in Matter. It is hardly necessary, after such authorities, to mention Dr. Johnson,

or any one else who resorts to the argumentum baculinum of knocking a stick against the ground. Sir W. Hamilton, a far subtler thinker than any of these, never reasons in this manner. He never supposes that a disbeliever in what he means by Matter, ought in consistency to act in any different mode from those who believe in it. He knew that the belief on which all the practical consequences depend, is the belief in Permanent Possibilities of Sensation, and that if nobody believed in a material universe in any other sense, life would go on exactly as it now does. He, however, did believe in more than this, but, I think, only because it had never occurred to him that mere Possibilities of Sensation could, to our artificialized consciousness, present the character of objectivity which, as we have now shown, they not only can, but unless the known laws of the human mind were suspended, must necessarily, present.

Perhaps it may be objected, that the very possibility of framing such a notion of Matter as Sir W. Hamilton’s—the capacity in the human mind of imagining an external world which is anything more than what the Psychological Theory makes it—amounts to a disproof of the theory. If (it may be said) we had no revelation in consciousness, of a world which is not in some way or other identified with sensation, we should be unable to have the notion of such a world. If the only ideas we had of external objects were ideas of our sensations, supplemented by an acquired notion of permanent possibilities of sensation, we must (it is thought) be incapable of conceiving, and therefore still more incapable of fancying that we perceive, things which are not sensations at all. It being evident however that some philosophers believe this, and it being maintainable that the mass of mankind do so, the existence of a perdurable basis of sensations, distinct from sensations themselves, is proved, it might be said, by the possibility of believing it.

Let me first restate what I apprehend the belief to be. We believe that we perceive a something closely related to all our sensations, but different from those which we are feeling at any particular minute; and distinguished from sensations altogether, by being permanent and always the same, while these are fugitive, variable, and alternately displace one another. But these attributes of the object of perception are properties belonging to all the possibilities of sensation which experience guarantees. The belief in such permanent possibilities seems to me to include all that is essential or characteristic in the belief in substance. I believe that Calcutta exists, though I do not perceive it, and that it would still exist if every percipient inhabitant were suddenly to leave the place, or be struck dead. But when I analyse the belief, all I find in it is, that were these events to take place, the Permanent Possibility of Sensation which I call Calcutta would still remain; that if I were suddenly transported to the banks of the Hoogly, I should still have the sensations which, if now present, would lead me to affirm that Calcutta exists here and now. We may infer, therefore, that both philosophers and the world at large, when they think of matter, conceive it really as a Permanent Possibility of Sensation. But the majority of philosophers fancy that it is something more; and the world at large, though they have really, as I conceive, nothing in their minds but a Permanent Possibility of Sensation, would, if asked the question, undoubtedly agree with the philosophers: and though this is sufficiently explained by the tendency of the human mind to infer difference of things from difference of names, I acknowledge the obligation of showing how it can be possible to believe in an existence transcending all possibilities of sensation, unless on the hypothesis that such an existence actually is, and that we actually perceive it.

The explanation, however, is not difficult. It is an admitted fact, that we are capable of all conceptions which can be formed by generalizing from the observed laws of our sensations. Whatever relation we find to exist between any one of our sensations and something different from it, that same relation we have no difficulty in conceiving to exist between the sum of all our sensations and something different from them. The differences which our consciousness recognises between one sensation and another, give us the general notion of difference, and inseparably associate with every sensation we have, the feeling of its being different from other things: and when once this association has been formed, we can no longer conceive anything, without being able, and even being compelled, to form also the conception of something different from it. This familiarity with the idea of something different from each thing we know, makes it natural and easy to form the notion of something different from all things that we know, collectively as well as individually. It is true we can form no conception of what such a thing can be; our notion of it is merely negative; but the idea of a substance, apart from its relation to the impressions which we conceive it as making on our senses, is a merely negative one. There is thus no psychological obstacle to our forming the notion of a something which is neither a sensation nor a possibility of sensation, even if our consciousness does not testify to it; and nothing is more likely than that the Permanent Possibilities of sensation, to which our consciousness does testify, should be confounded in our minds with this imaginary conception. All experience attests the strength of the tendency to mistake mental abstractions, even negative ones, for substantive realities; and the Permanent Possibilities of sensation which experience guarantees, are so extremely unlike in many of their properties to actual sensations, that since we are capable of imagining something which transcends sensation, there is a great natural probability that we should suppose these to be it. — Mill

There's so much insight pack in these passages that I'm surprised that Mill is not more talked about. It was Husserl's appreciated of the some of the English philosophers that got me looking into Mill and Berkeley. With Mill, so far, there's no theological baggage to step around.

All experience attests the strength of the tendency to mistake mental abstractions, even negative ones, for substantive realities.

I think Mill hits the nail on the head on this issue of the I-know-not-what that's supposed to be more than possible or actual experience : some kind of [ aperspectival ] Substance that's hidden forever behind or within whatever actually appears. It seems cleaner to understand reality itself as horizonal or transcendent, which is to say never finally given but also not hiding behind itself.

As far as I can tell, this isn't of much practical importance. But for those who find themselves wanting clarity and coherence with respect to fundamental concepts, it might feel like progress. -

plaque flag

2.7kLast one for now, I promise. Mill dissolves the subject too.

plaque flag

2.7kLast one for now, I promise. Mill dissolves the subject too.

https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/mill-the-collected-works-of-john-stuart-mill-volume-ix-william-hamiltons-philosophyWe have no conception of Mind itself, as distinguished from its conscious manifestations. We neither know nor can imagine it, except as represented by the succession of manifold feelings which metaphysicians call by the name of States or Modifications of Mind. It is nevertheless true that our notion of Mind, as well as of Matter, is the notion of a permanent something, contrasted with the perpetual flux of the sensations and other feelings or mental states which we refer to it; a something which we figure as remaining the same, while the particular feelings through which it reveals its existence, change. This attribute of Permanence, supposing that there were nothing else to be considered, would admit of the same explanation when predicated of Mind, as of Matter. The belief I entertain that my mind exists when it is not feeling, nor thinking, nor conscious of its own existence, resolves itself into the belief of a Permanent Possibility of these states. If I think of myself as in dreamless sleep, or in the sleep of death, and believe that I, or in other words my mind, is or will be existing through these states, though not in conscious feeling, the most scrupulous examination of my belief will not detect in it any fact actually believed, except that my capability of feeling is not, in that interval, permanently destroyed, and is suspended only because it does not meet with the combination of conditions which would call it into action: the moment it did meet with that combination it would revive, and remains, therefore, a Permanent Possibility.

He then tackles the concern that understanding the self as what I'd call a worldstreaming implies solipsism.

He somewhat follows Husserl and suggests that we have good reasons to infer or suppose that others are worldstreams too, though we don't have direct access to this streaming. And in the age of high tech and AI, we may eventually be faced with genuine perplexity. Does this thing feel? Does this thing see ? Note that (for me) we can't 'prove' that other humans are 'really' there, but most of us fortunately don't wrestle with living, genuine doubt.In the first place, as to my fellow-creatures. Reid seems to have imagined that if I myself am only a series of feelings, the proposition that I have any fellow-creatures, or that there are any Selves except mine, is but words without a meaning. But this is a misapprehension. All that I am compelled to admit if I receive this theory, is that other people’s Selves also are but series of feelings, like my own. Though my Mind, as I am capable of conceiving it, be nothing but the succession of my feelings, and though Mind itself may be merely a possibility of feelings, there is nothing in that doctrine to prevent my conceiving, and believing, that there are other successions of feelings besides those of which I am conscious, and that these are as real as my own. -

Janus

18kSo….he was mistaken in that he didn’t attribute real existence to space and time? Or, you think he should have? The theory holds that things-in-themselves possess real existence, and are the origin-in-kind of that which appears to sensibility. — Mww

Janus

18kSo….he was mistaken in that he didn’t attribute real existence to space and time? Or, you think he should have? The theory holds that things-in-themselves possess real existence, and are the origin-in-kind of that which appears to sensibility. — Mww

You'll probably disagree with me (we all have different ways of thinking about these things, apparently) but I see space and time as being for us, just as objects are, appearances. I think I can see spatial extension, and feel duration, just as I see and feel objects. So, for me the status of space and time is no different regarding the "in-itself" than is the case with things.

I think there is a real cosmos, which existed long before there was consciousness of any kind, and I think it always has been undergoing constant change, that it is extensive and always has been. I see time as change and duration, and space as extension, and I see no reason not to think those are real attributes of the cosmos, which do not rely for their existence on appearing to cognitive beings,

I realize that a cosmos without cognitive beings is in a sense "blind", it appears to nothing and no one, and in that sense, we might say that it is virtually non-existent, but I think that view is anthropocentric. Something does not need to be seen in order to be visible.

So, I interpret Kant's idea of in-itself as signifying that we know only what appears to us, which is not to say we know nothing of consciousness-independent real things, but that the reality of those things is not exhausted by how they appear to us and other cognitive beings.

I think many of these disagreements come down to preferred ways of talking, and underlying the apparent differences produced by different locutions there may be more agreement than there often appears to be. It is remarkable how important these metaphysical speculations seem to be to folk. I enjoy it as a creative exercise of the imagination. -

Wayfarer

26.2kKant didn’t saw off his own branch. — Mww

Wayfarer

26.2kKant didn’t saw off his own branch. — Mww

Exactly as I see it also.

The thinking, presenting subject; there is no such thing.

...

And from nothing in the field of sight can it be concluded that it is seen from an eye ~ Wittgenstein — TLP

I quoted from that in my MA thesis in Buddhist Studies. As I've said before, the self is never an object, yet the reality of the subject of experience ('what it is like to be....') is apodictic, cogito ergo sum. Where in the world is the metaphysical subject to be noted? Why, that would be 'nowhere', yet otherwise there is no world.

The objects of experience then are not things in themselves, but are given only in experience, and have no existence apart from and independently of experience. — Kant

The OP is pretty well an exercise in understanding how this can be true. (A successful one, I would like to think.)

Anyway, I perceive (interpret) this surrounding darkness as a deep blanket of threatening-promising possibility. — plaque flag

I once wrote a rather contemplative piece on the old forum, about how meditation is like learning to see in the dark. The analogy was that conscious thought brings everything into the pool of light around the campfire, but there's an awareness that outside that area there is a landscape and other creatures moving about that we're only dimly aware of and feel threatened by. The idea being that moving away from the pool of light and letting your eyes adjust to the moonlight, so you can see the contours of the landscape.

I think Mill hits the nail on the head on this issue of the I-know-not-what that's supposed to be more than possible or actual experience : some kind of [ aperspectival ] Substance that's hidden forever behind or within whatever actually appears. — plaque flag

Pinter's book, Mind and the Cosmic Order, starts with the British Empiricists, and their insistence that knowledge comes solely from sense experience. But he moves on to Kant who showed that there must be innate faculties :yikes: which organize and categorise sense-data, otherwise we would not be able to make sense of sense.

John Stuart Mill asserted that all knowledge comes to us from observation through the senses. This applies not only to matters of fact, but also to "relations of ideas," as Hume called them: the structures of logic which interpret, organize and abstract observations.

Against this, Kant argued that the structures of logic which organize, interpret and abstract observations were innate to mind and were true and valid a priori ('innateness' being anathema to the empiricists Hume and Mill).

Mill, on the contrary, said that we believe them (i.e. mathematical proofs) to be true because we have enough individual instances of their truth to generalize: in his words, "From instances we have observed, we feel warranted in concluding that what we found true in those instances holds in all similar ones, past, present and future, however numerous they may be".

Although the psychological or epistemological specifics given by Mill through which we build our logical apparatus may not be completely warranted, his explanation still inadevertantly manages to demonstrate that there is no way around Kant’s a priori logic. To restate Mill's original idea: “Indeed, the very principles of logical deduction are true because we observe that using them leads to true conclusions” - which is itself a deductive proposition!

For most mathematicians the empiricist principle that 'all knowledge comes from the senses' contradicts a more basic principle: that mathematical propositions are true independent of the physical world. Everything about a mathematical proposition is independent of what appears to be the physical world. It all takes place in the mind drawn from the infallible principles of deductive logic. It is not influenced by exterior inputs from the physical world, distorted by having to pass through the tentative, contingent universe of the senses. It is internal to thought, as it were. — Scrapbook Entry, from an archived version of the Wikipedia entry on Philosophy of Mathematics

(I'll also add in passing that traditional philosophy sees a relationship between the domain of the apriori and the invariance of scientific laws and regularities - another principle called into question in modern philosophy.) -

plaque flag

2.7kI quoted from that in my MA thesis in Buddhist Studies. As I've said before, the self is never an object, yet the reality of the subject of experience ('what it is like to be....') is apodictic, cogito ergo sum. Where in the world is the metaphysical subject to be noted? Why, that would be 'nowhere', yet otherwise there is no world. — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kI quoted from that in my MA thesis in Buddhist Studies. As I've said before, the self is never an object, yet the reality of the subject of experience ('what it is like to be....') is apodictic, cogito ergo sum. Where in the world is the metaphysical subject to be noted? Why, that would be 'nowhere', yet otherwise there is no world. — Wayfarer

'What it is like to be' is an interpretation of something prior to mind or non-mind. That's the way I'd go here. What interprets then ? If mind is not fundamental ? I'd go with some kind of emergent 'panlogical' timebinding. There is a subject, but it's cultural and emergent and self-positing. Spirit is a modification of nature. I don't pretend to explain this emergence. I prioritize [merely] articulating the given ---only a blurry-muddy-tentative foundation for further plausible speculation. -

Wayfarer

26.2kDon't get too diverted by it, there are many more important points to consider. That was simpy a passing allusion to David Chalmers. It's the connection between 'innateness', mathematical truths and rational principles that is the quarry.

Wayfarer

26.2kDon't get too diverted by it, there are many more important points to consider. That was simpy a passing allusion to David Chalmers. It's the connection between 'innateness', mathematical truths and rational principles that is the quarry. -

plaque flag

2.7kThe objects of experience then are not things in themselves, but are given only in experience, and have no existence apart from and independently of experience. — Kant

plaque flag

2.7kThe objects of experience then are not things in themselves, but are given only in experience, and have no existence apart from and independently of experience. — Kant

The OP is pretty well an exercise in understanding how this can be true. — Wayfarer

I really like the bolded part of the Kant quote, but I find it in tension with the first part. The objects are given only in experience and don't exist otherwise. So what in the world (but of course not in the world, which is exactly the problem) is left over ? -

plaque flag

2.7kBut he moves on to Kant who showed that there must be innate faculties :yikes: which organize and categorise sense-data, otherwise we would not be able to make sense of sense. — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kBut he moves on to Kant who showed that there must be innate faculties :yikes: which organize and categorise sense-data, otherwise we would not be able to make sense of sense. — Wayfarer

It'd be very un-Kantian to make those faculties more than structures or possibilities of experience. I have not the least objection to psychological entities like memory, but I'd say these faculties are mere postulations for explaining a structure in the experience that is first and foremost just there.

Heidegger does his own Kantian thing in articulating the care-structure of this world-streaming being-there. An evolutionary psychologist might postulate how expectation in the context of memory maximizes the average number of offspring. Which is fine. But the existence of that care structure (existence as that enworlded care structure) is primary. Explanations are secondary and tentative. This to me is part of phenomenological bracketing. Let's articulate what's there first, before we jump into theorizing. -

Wayfarer

26.2kSpirit is a modification of nature. — plaque flag

Wayfarer

26.2kSpirit is a modification of nature. — plaque flag

On the contrary - doesn't C S Peirce say that 'matter is effete mind'?

So what in the world (but of course not in the world, which is exactly the problem) is left over? — plaque flag

though we know that prior to the evolution of life there must have been a Universe with no intelligent beings in it, or that there are empty rooms with no inhabitants, or objects unseen by any eye — the existence of all such supposedly unseen realities still relies on an implicit perspective. What their existence might be outside of any perspective is meaningless and unintelligible, as a matter of both fact and principle.

Which, now that I reflect further, suggests 'that of which we cannot speak....'

It'd be very un-Kantian to make those faculties more than structures or possibilities of experience. — plaque flag

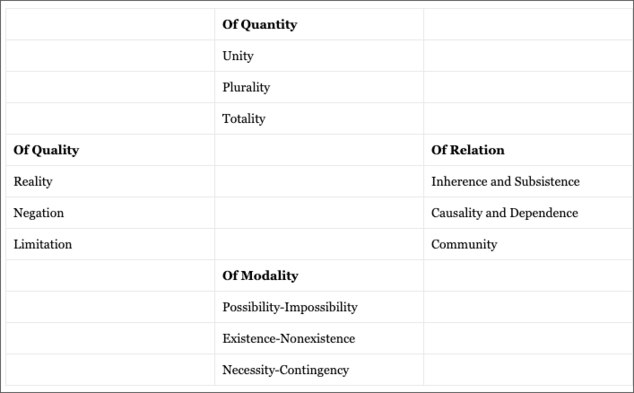

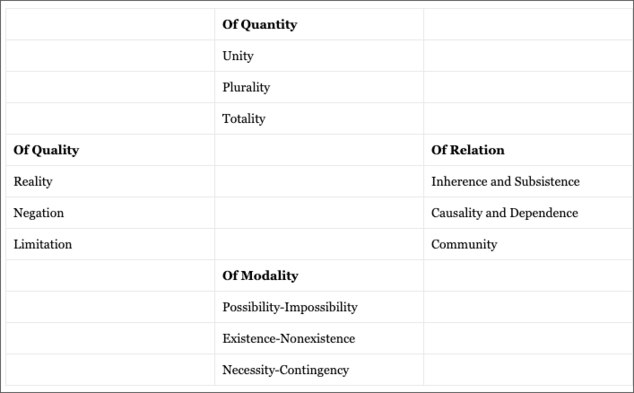

According to IEP, Kant adopted Aristotle's categories, with some slight modifications.

They do indeed 'structure' experience, but they're not derived from experience. That's what makes them 'transcendental'. -

plaque flag

2.7kAlthough the psychological or epistemological specifics given by Mill through which we build our logical apparatus may not be completely warranted, his explanation still inadevertantly manages to demonstrate that there is no way around Kant’s a priori logic. To restate Mill's original idea: “Indeed, the very principles of logical deduction are true because we observe that using them leads to true conclusions” - which is itself a deductive proposition! — Scrapbook Entry, from an archived version of the Wikipedia entry on Philosophy of Mathematics

plaque flag

2.7kAlthough the psychological or epistemological specifics given by Mill through which we build our logical apparatus may not be completely warranted, his explanation still inadevertantly manages to demonstrate that there is no way around Kant’s a priori logic. To restate Mill's original idea: “Indeed, the very principles of logical deduction are true because we observe that using them leads to true conclusions” - which is itself a deductive proposition! — Scrapbook Entry, from an archived version of the Wikipedia entry on Philosophy of Mathematics

I agree that Mill was guilty of psychologism on the issue of logic. But this doesn't establish some kind of metaphysical machinery hidden in the Self. Indeed, I'm more inclined to take a Hegel-Heidegger path here and emphasize that the self (as normative-ethical-linguistic locus of freedom-responsibility ) is largely and even mostly a social entity, a performance of and participation of norms, including logical-semantic norms. We performing such norms right now, as we try to articulate and explain those very norms within a framework of adversarial cooperation.

As far as I can tell, Kantian logical machinery wouldn't work anyway. How can a 'machine' (a mere faculty) give us a normative 'output' ? Unless you are invoking some kind of mystical supernatural 'biology,' it's not clear how this wouldn't be more psychologism. 'We are programmed to be logical.' Normativity seems pretty irreducible. Invoking faculties doesn't seem to help us here, for is that not equivalent to evolutionary biology, except in an opposite 'theological biology' flavor ? -

plaque flag

2.7kOn the contrary - doesn't C S Peirce say that 'matter is effete mind'? — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kOn the contrary - doesn't C S Peirce say that 'matter is effete mind'? — Wayfarer

I grant that we could also read the thing backwards, with nature as a 'segment' of spirit. We create the scientific image from within an encompassing lifeworld. It depends on whether we are reasoning 'outwards' from where we always already are (the enabling assumptions of ontology) or trying to tell a plausible story of how we ended up here.

To me it's implausible for us to deny that we inherit centuries of development, and our best biological stories extend this to millions of years. -

Mww

5.4kYou'll probably disagree with me (we all have different ways of thinking about these things, apparently) but I see space and time as being for us, just as objects are, appearances. — Janus

Mww

5.4kYou'll probably disagree with me (we all have different ways of thinking about these things, apparently) but I see space and time as being for us, just as objects are, appearances. — Janus

Oh, I certainly do, but there’s no damage done by it. Different strokes and all that, right?

Is it a precept or some kind of general rule of phenomenology that space and time are appearances in the same way as objects? Say, as in Kant for instance, appearance mandates sensation relating specifically to it, what sensation could we expect of space from its appearance? Or is it that the precept or rule doesn’t demand sensation from appearance?

————-

I think there is a real cosmos….. — Janus

As do I, and grant the rest of that paragraph, given your perspective.

Lemme ask you this: there is in the text the condition that space is allowed “empirical reality in regard to all possible external experience”. Would you accept that his empirical reality is your appearance?

————-

I think many of these disagreements come down to preferred ways of talking — Janus

Yeah, could be. But you know me….I shun language predication like the plague: rather kill it than put up with it. But you’re right, insofar as there must be something that grounds disagreements, so I vote for disparity in subjective presuppositions. How one thinks about stuff depends exclusively on where he starts with it. -

plaque flag

2.7kWhich, now that I reflect further, suggests 'that of which we cannot speak....' — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kWhich, now that I reflect further, suggests 'that of which we cannot speak....' — Wayfarer

Ancestral objects are a totally reasonable concern, but I think they've already been covered by Mill's theory of possible experience. The meaning of an ancestral statement ('there used to be these giant lizards') is something like: if we had a time machine, we could go back and see those famous dinosaurs. Now some physical theories (11 dimensional, etc.) are impossible to even imagine, and I'd class them with what Kojeve calls 'the silence of algorithm.' The meaning of those theories only comes into focus with predictions that are finally 'within' the sensibility of the lifeworld. Note that chatbots use a mathematics of millions and even billions of 'dimensions.'

Something like Hegelian semantic holism is central here. No finite or radically disconnect entity has genuine being, because it'd literally be nonsense. Sense is structural-relational. That sort of thing. To explain a cat you need to explain a mouse. Single concepts (a language with only one) don't make sense (Sellars/Brandom). -

plaque flag

2.7kThey do indeed 'structure' experience, but they're not derived from experience. That's what makes them 'transcendental'. — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kThey do indeed 'structure' experience, but they're not derived from experience. That's what makes them 'transcendental'. — Wayfarer

But all apriori knowledge is fished out of experience in the first place. Patterns in experience are noticed, articulated, and then [now consciously] relied upon. Even the early geometers had to 'see' or notice certain patterns in the first place, till they finally organized an axiomatic theory for the efficient communication of this insight to others.

The German phenomenologist Edmund Husserl wrote a famous essay, “The Origin of Geometry” that called for a new kind of “historical” research, to recover the “original” meaning of geometry, to the man, whoever he was, who first invented it.

It seems to me not that hard to imagine the origin of geometry. Once upon a time, even twice or several times, someone first noticed some simple facts. For example, when one stick lies across another stick, there are four spaces that you can see. You can see that they are equal in pairs, opposite to opposite. It happened something like this, perhaps at some campfire, 20 or 30,000 years ago.

https://math.unm.edu/~rhersh/geometry.pdf -

plaque flag

2.7kFor most mathematicians the empiricist principle that 'all knowledge comes from the senses' contradicts a more basic principle: that mathematical propositions are true independent of the physical world. Everything about a mathematical proposition is independent of what appears to be the physical world. — Scrapbook Entry, from an archived version of the Wikipedia entry on Philosophy of Mathematics

plaque flag

2.7kFor most mathematicians the empiricist principle that 'all knowledge comes from the senses' contradicts a more basic principle: that mathematical propositions are true independent of the physical world. Everything about a mathematical proposition is independent of what appears to be the physical world. — Scrapbook Entry, from an archived version of the Wikipedia entry on Philosophy of Mathematics

I loved Pinter's book on abstract algebra, and such algebra is a great example of abstraction. Group theory ignores absolutely everything about a system except its satisfaction of a few simple axioms. This allows for a rich theory that applies to all possible groups at once, even those not yet invented or discovered. But this theory still exists in the world as an intellectual tradition. It uses symbols to support a thinking which is basically immaterial. (I'm not a formalist. Math gives insight.) The theory is also temporal-historical. No mathematician can hold it all in their intuition at once. He or she can review the forgotten proof/justification of a theorem. Can reason (and often does) in terms of Assuming P, then ...

I don't know how seriously we should take 'physical world' if we've already granted that the being of the world is essentially perspectival --that physicality is derivative and conventional --- understood in terms of possible and actual experience. -

Janus

18kOr is it that the precept or rule doesn’t demand sensation from appearance? — Mww

Janus

18kOr is it that the precept or rule doesn’t demand sensation from appearance? — Mww

It's not a precept or rule of phenomenology as far as I am aware, it's just my own take. I realize of course that space and time are not sense objects as trees, smells and sounds are, but I stll think that we see extension and feel duration.

That aside, if the things as they are in themselves is unknowable I think we then have no warrant for claiming that it is not spatiotemporal. Of course, it would presumably not be spatiotemporal in the same way as appearances are, but it seems plausible to think that it must be such as to give rise to the spatiotemporal things, and I don't find the idea that that is entirely down to the mind convincing.

All that said I acknowledge that the mind or consciousness could possibly be ontologically foundational, I just tend to lean the other way.

Lemme ask you this: there is in the text the condition that space is allowed “empirical reality in regard to all possible external experience”. Would you accept that his empirical reality is your appearance? — Mww

Yes, I find that idea acceptable. But if we want to go beyond phenomenalism and speculate as to what could give rise to that empirical reality, then I think we find ourselves entirely in the realm where the individual sense of plausibility rules.

Yeah, could be. But you know me….I shun language predication like the plague — Mww

And I think I share (at least some of) your concerns about OLP. I could just as easily have said "preferred ways of thinking" as I have little doubt that our preferred ways of talking reflect that. -

Wayfarer

26.2kHow can a 'machine' (a mere faculty) give us a normative 'output' ? — plaque flag

Wayfarer

26.2kHow can a 'machine' (a mere faculty) give us a normative 'output' ? — plaque flag

There's nothing mechanical about reason. Reason is the relation of ideas. And the reason why it seems 'metaphysical' is because, as we already established, you look with it, not at it. We can't know it, because it is what is knowing. That's what 'the eye can't see itself' means. Not understanding that is behind innummerable confusions about the nature of logic and mathematics.

Re geometery - I read a compelling account that the foundations of geometery were laid by the requirement to mark out parcels of land-holdings on the ancient Nile delta for each planting season, after the annual floods had re-arranged the landscape. Makes perfect sense to me. But that still doesn't explain the faculty of being able to count and calculate. As I understand it, Husserl grounds arithmetic in the act of counting. (I have the idea that this actually dovetails with Aquinas' idea of 'being as a verb'. So arithmetic, even though it comprises 'unchanging truths' on the one hand, is also inherently dynamic, in that grasping it is an activity of the intellect.)

Note that chatbots use a mathematics of millions and even billions of 'dimensions.' — plaque flag

I'm having great experiences with ChatGPT4 - it's just amazing for bouncing ideas off and generating other ideas. I call it, not 'artificial' intelligence, but 'augmented' intelligence.

I loved Pinter's book on abstract algebra, and such algebra is a great example of abstraction. Group theory ignores absolutely everything about a system except its satisfaction of a few simple axioms. This allows for a rich theory that applies to all possible groups, even those not yet invented or discovered. But this theory still exists in the world as an intellectual tradition. It uses symbols to support a thinking which is basically immaterial. (I'm not a formalist. Math gives insight.) — plaque flag

Right! I had noticed Pinter's books on abstract algebra, although not being a mathematician, they probably wouldn't mean much to me. But do look at the abstract of his Mind and the Cosmic Order, I'm sure you'd like it.

algebra is a great example of abstraction — plaque flag

Even though this quotation is about geometry and astronomy (as algebra hadn't yet been invented), it still rings true to me:

It is indeed no trifling task, but very difficult to realize that there is in every soul an organ or instrument of knowledge that is purified and kindled afresh by such studies (as geometry and astronomy) when it has been destroyed and blinded by our ordinary pursuits, a faculty whose preservation outweighs ten thousand eyes; for by it only is reality beheld (because by it the eternal principles are beheld). Those who share this faith will think your words superlatively true. But those who have and have had no inkling of it will naturally think them all moonshine. For they can see no other benefit from such pursuits worth mentioning. Decide, then, on the spot, to which party you address yourself. — Republic 527d -

plaque flag

2.7kReason is the relation of ideas. And the reason why it seems 'metaphysical' is because, as we already established, you look with it, not at it. We can't know it, because it is what is knowing. — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kReason is the relation of ideas. And the reason why it seems 'metaphysical' is because, as we already established, you look with it, not at it. We can't know it, because it is what is knowing. — Wayfarer

I'll agree with you partially here, on Heideggarian terms. Our fundamental form of being is a kind of 'subrational' understanding or knowhow or skill. And we live in language like a water lives in fish (I'm keeping this accidental reversal in, because it's fun.) We rely upon this blind skill in order to even begin to articulate our own ability to articulate. Our minds are an especially 'transcendent' object in the Husserlian sense ---the most complicated, manifold, and 'horizonal' of familiar entities. -

Wayfarer

26.2kRight. Dasein as being 'thrown into' existence. (Anamnesis, remembering how it happened, although I don't think that's in Heidegger.)

Wayfarer

26.2kRight. Dasein as being 'thrown into' existence. (Anamnesis, remembering how it happened, although I don't think that's in Heidegger.) -

plaque flag

2.7kAs I understand it, Husserl grounds arithmetic in the act of counting. (I have the idea that this actually dovetails with Aquinas' idea of 'being as a verb'. So arithmetic, even though it comprises 'unchanging truths' on the one hand, is also inherently dynamic, in that grasping it is an activity of the intellect.) — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kAs I understand it, Husserl grounds arithmetic in the act of counting. (I have the idea that this actually dovetails with Aquinas' idea of 'being as a verb'. So arithmetic, even though it comprises 'unchanging truths' on the one hand, is also inherently dynamic, in that grasping it is an activity of the intellect.) — Wayfarer

:up:

Have you ever seen rectangles of dots used to prove the commutative law ? Very persuasive. For me math is more visual than temporal, though it's grasped in time. Peirce thought of it in terms of diagrams. I think he was right, but that might be my visual bias talking. Others might 'see' the same mathematical objects differently. As long as people agree on their nature, it'd be hard to know. Sort of like the red-green reversal issue. -

plaque flag

2.7kRight. Dasein as being 'thrown into' existence. (Anamnesis, remembering how it happened, although I don't think that's in Heidegger.) — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kRight. Dasein as being 'thrown into' existence. (Anamnesis, remembering how it happened, although I don't think that's in Heidegger.) — Wayfarer

Indeed, and it's like being thrown into a kind of driving or sleepwalking. We are thrown into doing things the Right way. One eats with a fork, says please and thank you, doesn't walk outside without pants on. One circumspectively takes a couch as something for sitting on. And, as we've discussed, one looks right through the way that objects are given to their practical relevance. In our culture, one learns that the human is a rational animal in the system of nature, and not of course (how silly ! ) the very site of being. Also religion is a Private Matter. I don't object to this last one, but I notice it. I'm aware that it emerged after centuries of something else.

I like Heidegger's phrase which is translated as 'falling immersion.' Our tendency is to fall back into the cultural default, which is not all bad, because plenty of conventions are justified. -

Wayfarer

26.2kWe are thrown into doing things the Right way. — plaque flag

Wayfarer

26.2kWe are thrown into doing things the Right way. — plaque flag

except for when we don't, which seems to happen an awful lot. -

plaque flag

2.7kexcept for when we don't, which seems to happen an awful lot. — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kexcept for when we don't, which seems to happen an awful lot. — Wayfarer

Sure, we are a wicked bunch, and there's an entire tradition with a right way for talking about that.

I've been reading some mathematical biology stuff, and it all makes a sick kind of sense. It's almost tautological that the world is snafu, given certain plausible assumptions and mathematical theorems. Life 'is' exploitation in a certain sense, with altruism 'forming' the inside of a larger organism (my group against yours.) I'm following the mess in Israel, and it's the same old history is a nightmare from which I'm trying to awake. -

Wayfarer

26.2kWell, Heidegger was according to some readings still pre-occupied with the fallen state of humanity. I think the absence of that kind of sense from secular humanism is a yawning gulf. It seems we (i.e. Steve Pinker) just want to make the world like a five-star resort. And it ain't going so well.

Wayfarer

26.2kWell, Heidegger was according to some readings still pre-occupied with the fallen state of humanity. I think the absence of that kind of sense from secular humanism is a yawning gulf. It seems we (i.e. Steve Pinker) just want to make the world like a five-star resort. And it ain't going so well.

Yes, the accounts from Israel are absolutely shattering and heart-breaking, aside from being absolutely bloody terrifying, although there is a separate thread on that (although I'm refraining from general comments, it will only add to the hubbub.) -

Mww

5.4kThey do indeed 'structure' experience, but they're not derived from experience. That's what makes them 'transcendental'. — Wayfarer

Mww

5.4kThey do indeed 'structure' experience, but they're not derived from experience. That's what makes them 'transcendental'. — Wayfarer

Hume’s dilemma, and a logical snafu: it is impossible to both structure, and be derived from that which is structured. Build a house with boards, and the house gives you the boards? Say wha..!?!?

I jest, but the principle holds.

————-

I could just as easily have said "preferred way of thinking" as I have little doubt that our preferred ways of talking reflect that. — Janus

I might argue that point. Ya know….we cannot think a thing then think we have thought otherwise, but we can think a thing and talk about it as if we thought of it otherwise. You cannot fake your thoughts but you can fake your language regarding your thoughts.

…..it's just my own take. — Janus

Cool. -

plaque flag

2.7kWell, Heidegger was according to some readings still pre-occupied with the fallen state of humanity. — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kWell, Heidegger was according to some readings still pre-occupied with the fallen state of humanity. — Wayfarer

I agree that Heidegger was influenced, etc., though I personally have no trouble yanking 'falling immersion' and many other concepts into a secular/'universal' context. I can't speak for others, but I'm interested in the work as a body of potential insight which can be personally sifted and tested. Part of the attraction of phenomenology is its deeply anti-authority check-for-yourself spirit. It's also largely descriptive, simply pointing out what's typically overlooked, eschewing fancy uncertain constructions. -

plaque flag

2.7k

plaque flag

2.7k

One of my concerns about hidden-in-principle stuff in the self is that it leads us back into dualism. If to be is to be [potentially ] perceived or experienced, then nothing is [ absolutely ] hidden. If the world exists perspectively for 'transcendental' subjects which are ultimately nondual, then the deep structure of the subject must exists as manifest, both in the structure of the worldstreaming and then in the conceptual layer of this streaming as part of an intellectual culture that unveils it. The 'self in itself' which is 'infinitely' hidden ruins the whole nondual project, it seems to me.

I do acknowledge the obvious reality and intensity of memory and fantasy. And obviously we have the concept of both faculties, but I'd say the meaning of such faculties is ultimately in actual memories and fantasies that we've learned to classify. The lifeworld is always already culturally structured, and that includes interpretations of 'inner' states (and our sense of them as inner as opposed to outer, mine and not ours.)

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum