-

Antony Nickles

1.4kOne of my favorite books @Banno, thanks for doing this (good luck).

Antony Nickles

1.4kOne of my favorite books @Banno, thanks for doing this (good luck).

There's the bit where you say it and the bit where you take it back. — Austin

"What we should figure out, is knowledge... well, we tried. Then virtue!... nope, not that either." Plato

"Let's start with the thing-in-itself; and then set it over here behind this wall." Kant

"I exist! Or, if that's okay with you God." Descartes

"I see it! No, wait, that's only its appearance." Hume

His target is the idea that we only ever see things indirectly. — Banno

I think Austin is wrong to quibble about the terms “direct” and “indirect”, because both succinctly describe the relationship between perceiver and perceived as it pertains to the arguments for and against realism…. But in terms of realism, “directly” and “indirectly” describe the perceptual relationship between the man and everything he perceives, which includes the periscope, the air, the clouds, etc. — NOS4A2

He’s investigating how we see something directly by looking at the actual cases when we do, and then how we see something indirectly through different examples, to show that philosophy made up the problem of realism. I think the book might be interesting to you.

This talk of “not directly perceiving objects” makes me wonder, not for the first time, who Austin believed he was arguing against. Did he think that Idealism in general, or versions of Kantianism in particular, entailed such a view? I don’t think that’s a very charitable interpretation of what I take Kant and others to be saying — J

Wittgenstein will look further into why philosophy created a problem with sense perception, belief, appearance, subjectivity, etc., but Austin is taking down everybody’s problematizing of the issues which led to metaphysics and justified true belief and Ayer’s Atomism and Positivism and qualia, etc. because they all have in common that they want everything to work one way that allows for absolute universal, generalized, proven, predictable, etc., knowledge. There’s a reason we get stuck on logical/emotive, true/false, knowledge/belief, etc. and that is because we are only looking at one version that is resolved one way, as, in the case of perception:

The reason is simple: "There is no one kind of thing that we perceive, but many different kinds" — Banno

Austin - Sense and Sensibilia 1962; Wittgenstein - Philosophical Investigations 1958. They never met, but they should have. Wittgenstein will look at how we think a bunch of things work, like language, and rules, seeing, identifying color, etc., and decide there is not one way we judge how things work, but many different ways.

[Looking at false dichotomies like direct/indirect] is a standard critical tool for Austin, used elsewhere to show philosophical abuse of "real". — Banno

In A Plea for Excuses, he will label this “The Importance of Negations and Opposites” in a discussion of freewill based on looking at action—using another tool of Austin’s, which is to look at how something works by looking at how it doesn’t work, how it goes wrong; in the case of action, by looking at how we excuse it, qualify it, renounce it, etc.—he actually looks at how voluntary and involuntary are so different it doesn’t make sense to manufacture the issues as: was that done freely (voluntarily)? or was it determined (involuntarily)?

(emphasis added by Nickles)And it is certainly true that we construct the correct shape from a multiplicity of individual "takes." …In Russell's sense of "real" -- a perception that corresponds fortuitously to an actual shape — J

(emphasis added by Nickles)The real table, if there is one, is not immediately known to us at all, but must be an inference from what is immediately known. If there are any directly perceived objects at all for Russell, they are sense data, not tables — Jamal

I can’t recommend reading this book more; Austin will have a lot to say about philosophy’s use of these words. Austin causes us to reconsider why philosophy creates a problem so it can solve it (@J why is the shape “correct” and “actual”, and not just roughly? - @jamal what does perception have to be immediate and direct in order to ensure? (spoiler!: it’s because we only want to answer one way, to one standard.)

talk of deception only makes sense against a background in which we understand what it is like not to be deceive. — Banno

Elsewhere he will say, basically, "intention" only makes sense (compared to imagining it as a cause) when someone does something "fishy" against a background in which we have ordinary, shared expectations. As in, "Did you intend to run that light?"

But notice that the contrast between philosophers and ordinary folk is borrowed from Ayer. — Banno

I just want to add that a common confusion is that Austin's method is pitting regular ol' common-sense people against esoteric philosophers, or as if “ordinary” was popularity—just taking a study, as if his philosophy was sociology. The common folk are all of us together who work within Wittgenstein's various criteria that are “ordinary” only compared to the single "prefabricated, metaphysical" criteria of certain, justified knowledge that philosophy uses. -

Jamal

11.6k

Jamal

11.6k

I'm not angry or anything, but I really hate being misquoted. Shown below is how it went: a quotation from Russell followed by my summary of his view with regard to the directness of perception:

The real table, if there is one, is not immediately known to us at all, but must be an inference from what is immediately known. — Russell

If there are any directly perceived objects at all for Russell, they are sense data, not tables. — Jamal

Carry on :smile: -

Antony Nickles

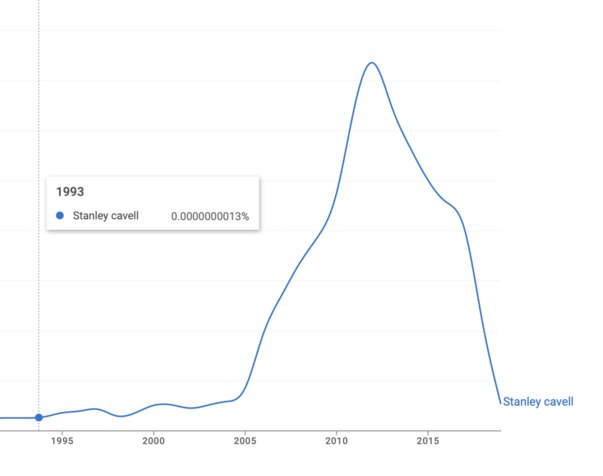

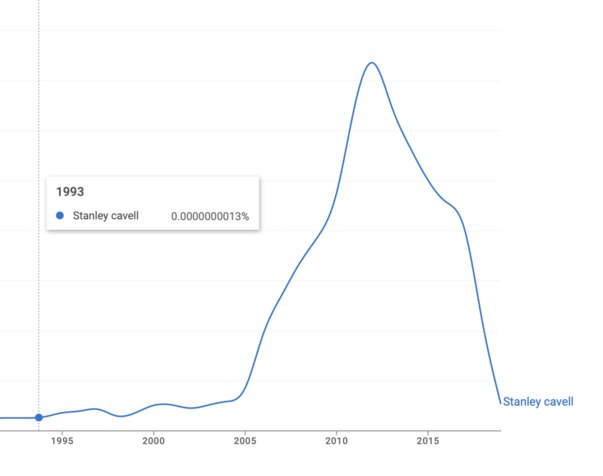

1.4kA quick look at Austin's book ngram shows continuous, perhaps even exponential, growth. — Banno

Antony Nickles

1.4kA quick look at Austin's book ngram shows continuous, perhaps even exponential, growth. — Banno

There goes my degree. -

Antony Nickles

1.4k

Antony Nickles

1.4k

I really hate being misquoted — Jamal

OOHH.... that is entirely my bad. I was rushing and crammed your sentence in with Russell's, probably among other errors. Apologies. And if I ran roughshod over your point or concerns, I jumped the gun a bit on assessing them I'm sure. I'm just a little excited to have anyone talking about this book. -

Jamal

11.6kNo worries. I have the book and have read it a couple of times. I like it, but I don't know if I'll be joining in this discussion. I'll be reading along though.

Jamal

11.6kNo worries. I have the book and have read it a couple of times. I like it, but I don't know if I'll be joining in this discussion. I'll be reading along though. -

Antony Nickles

1.4k@“J” @“Jamal”

Antony Nickles

1.4k@“J” @“Jamal”

I was thinking @“Banno” that I’ll just follow along in the book and ask when there’s something I never got about this, and then we can all make the most sense out of what he’s saying before we jump to judging the argument. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Cheers. I'm not claiming any expertise here, just an interest and an enjoyment of his style, even recognising its many flaws.good luck — Antony Nickles

I already missed a few things, and may go back and edit what I've already said.

Anyway. -

Antony Nickles

1.4k[Arguments against Ayer] 4. …it is also implied, even taken for granted, that there is room for doubt and suspicion” - Austin — Austin

Antony Nickles

1.4k[Arguments against Ayer] 4. …it is also implied, even taken for granted, that there is room for doubt and suspicion” - Austin — Austin

For how can I go so far as to try to use language to get between pain and its expression? — Witt, PI 245

Can't we imagine a rule determining the application of a rule, and a doubt which it removes—and so on? But that is not to say that we are in doubt because it is possible for us to imagine a doubt. — Wittgenstein, PI#84 -

Banno

30.6kIII

Banno

30.6kIII

The primary purpose of the argument from illusion is to induce people to accept

'sense-data' as the proper and correct answer to the question what they perceive on certain abnormal, exceptional occasions; but in fact it is usually followed up with another bit of argument intended to establish that they always perceive sense-data. Well, what is the argument? — p.20

Here he outlines the argument from illusion, hinting at the shenanigans he sees in its structure. Austin will show how Ayer has oversimplified, even misdiagnosed, the case for these abnormal instances, why we should reject 'sense-data' as a solution, and then that generalising to all perceptions is absurd.

Austin's dissection is minute and thorough.

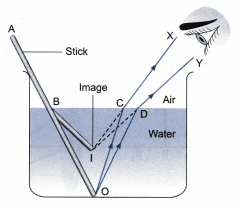

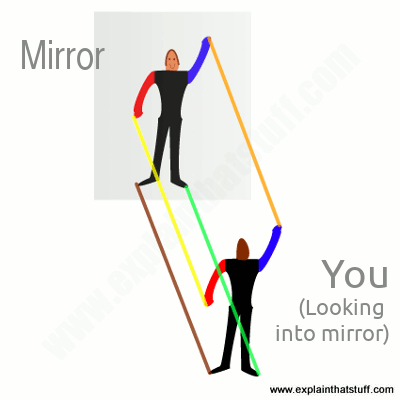

The three examples on the next page are central: A stick that appears bent in water because of refraction; A mirage; and a reflection in a mirror. I'll give a bit of background on each.

The physics of the stick is straight forward.

A stick or a pencil half immersed in water at an angle appears bent due to refraction of light at the air-water surface. Figure shows a straight stick AO whose lower portion BO is immersed in water. It appears to be bent at point B in the direction BI. A ray of light OC coming from the lower end O passes from water into air at C and gets refracted away from the normal in the direction CX.Another ray OD gets refracted in the direction DY. The two refracted ray CX and DY, when produced backward, appear to meet at point I, nearer to the water surface than O. Similarly each part of the immersed portion of the stick raised. As a result immersed portion of the stick appears to be bent when viewed at an angle from outside. — Discourse

The mirage example is a bit unclear.

Presumably the "thing" that is supposed not to exist is the body of water...Thus, when a man sees a mirage in the desert, he is not thereby perceiving any material thing , for the oasis which he thinks he IS perceiving does not exist — Ayer, p. 4

...in which the tree appears to be reflected, not the tree, which does exist. This image shows a possible result:

The ship, of course, exists. Ayer's example is not the best.

Mirror images are familiar, and well-understood.

Of course, the stuff in the mirror is "the wrong way around" - usually.

There's no mystery here, all accepted physics. -

Banno

30.6kYes, I was somewhat concerned not to present Wittgenstein's view. Here:

Banno

30.6kYes, I was somewhat concerned not to present Wittgenstein's view. Here:

Moore might have said "If this is not a real hand then I don't know what is." So either this is a real hand, and we are good, or we have no idea what a real hand might be.I look at a chair a few yards in front of me in broad daylight, my view is that I have (only) as much certainty as I need and can get that there is a chair and that I see it. But in fact the plain man would regard doubt in such a case, not as far-fetched or over- refined or somehow unpractical, but as plain nonsense; he would say, quite correctly, 'Well, if that's not seeing a real chair then I don't know what is.' — S&S p.10 -

frank

18.9k

frank

18.9k

Sometimes there is reason to doubt what you're experiencing, say if they just gave you ketamine and you're now convinced you're a character in a video game, screaming "I'm not real! I'm not real!" That happened, btw.

But if no one is telling you that you're drugged and hallucinating, you probably would just take the whatever as real. -

Jamal

11.6kA lame question, but I'm fairly new to the forum: How do I make those arrow+name graphics that mean "view original post"? — J

Jamal

11.6kA lame question, but I'm fairly new to the forum: How do I make those arrow+name graphics that mean "view original post"? — J

Reply using the reply button at the bottom of every post, as shown below.

It only appears when you hover over the post, i.e., when you put your mouse pointer in that area of the page.

On mobile you have to click the ellipsis to see the reply button. On mobile the ellipsis is at the bottom of every post.

For quoting, see this guide:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/13892/forum-tips-and-tricks-how-to-quote -

J

2.4kJ why is the shape “correct” and “actual”, and not just roughly? — Antony Nickles

J

2.4kJ why is the shape “correct” and “actual”, and not just roughly? — Antony Nickles

I don't quite get your question. Could you say more? Do you mean that it would be more accurate to say "roughly correct" or "very good approximation of the actual shape"? If so, no problem. -

javi2541997

7.2kBut if no one is telling you that you're drugged and hallucinating, you probably would just take the whatever as real. — frank

javi2541997

7.2kBut if no one is telling you that you're drugged and hallucinating, you probably would just take the whatever as real. — frank

Good point, I tried to share the same thought as you did previously when I attached a brief PDF of Richard A. Fumerton.

I think this author points out interesting views such as:How do we know when there is and when there is not a real object?: An argument from the possibility of hallucination" proves that naive realism is wrong, meaning that, "we are never directly acquainted with the fact that a physical object exists..." — Fumerton

We sometimes see things incorrectly; therefore, we never see them correctly.

But it is obvious that some see this point as invalid...

Yet, again, it seems that you and me, are the ones who are interested in 'hallucination' regarding this topic, Frank. -

Corvus

4.8kAustin will show how Ayer has oversimplified, even misdiagnosed, the case for these abnormal instances, why we should reject 'sense-data' as a solution, and then that generalising to all perceptions is absurd — Banno

Corvus

4.8kAustin will show how Ayer has oversimplified, even misdiagnosed, the case for these abnormal instances, why we should reject 'sense-data' as a solution, and then that generalising to all perceptions is absurd — Banno

I feel that Ayer's sense data theory is more reasonable. If everything you perceive is real, and that is it, it sounds too simple, and it has no ground to explicate what happens after your perception with the perceived content.

When you look at the perceived content as sense data, you could say that the sense data is stored in your memory, which you could retrieve and manipulate i.e. imagine, analyse, remember, synthesise etc throughout time and time after the perception.

Perception is far more than just to say, what I see is "real", and that is it. The aftermath of perception is more complex, deep, rich and meaningful in human perception.

Without some sort of repository place for the perceived content i.e. sense data, everything ends abruptly, there is no more to be said.

For the realists, there is no room to say anything more on the perception than a chair is chair - that is real, which is too simple. How do they further explain on remembering, imagining, and intuiting, and analysing ...etc? A chair was a char. But you cannot know anything afterwards. Blank. -

frank

18.9kYet, again, it seems that you and me, are the ones who are interested in 'hallucination' regarding this topic, Frank. — javi2541997

frank

18.9kYet, again, it seems that you and me, are the ones who are interested in 'hallucination' regarding this topic, Frank. — javi2541997

I couldn't conclude that we never see things correctly due to the possibility of hallucination. Detecting an hallucination presupposes that at some point I determined what was real to some suitable level of certainty.

What the possibility of hallucination does is confirm that there certainly is very good reason to occasionally doubt what you're seeing. For instance, a 15 year old boy with new onset schizophrenia tells his parents that he's hearing voices telling him to do harm to the people around him. He is in a state of doubt. He's looking for guidance. If he finds himself in the 21st century, the people around him will tell him the voices aren't real. If it was the year 1410, he would be told that he is possessed. So the resolution of his doubt really comes down to the hinge propositions of his time. It does not come down to some absurd rule that there's never reason to doubt your senses.

But indirect realism isn't a matter of saying that we never see what's real. The indirect realist does believe she has access to the truth. She just thinks her access to truth is indirect by her definition of indirectness. You don't have to be a direct realist to be a realist. Obviously. -

javi2541997

7.2kI agree.

javi2541997

7.2kI agree.

Basically, I think that reality does exist objectively. At least, there has to be something which exists at all. Because if we conclude that something doesn't exist, then it existed before, necessarily, because the latter precedes the second.

The debate goes on when Fumerton himself keeps denying realism because, according to him, it is difficult to reckon a physical object due to how the world is dependent upon our mental states.

In our experience we are, perhaps, directly acquainted with the facts concerning our mental states, but the possibility that experiences are hallucinations proves that we cannot be directly acquainted with the facts concerning physical objects that, beyond our reckoning, may or may not be causes of our experiences.

What makes me wonder if it is possible to experience reality from an objective perspective. -

Antony Nickles

1.4kDo you mean that it would be more accurate to say "roughly correct" or "very good approximation of the actual shape"? — J

Antony Nickles

1.4kDo you mean that it would be more accurate to say "roughly correct" or "very good approximation of the actual shape"? — J

I’m saying that “correct” is made up as a part of the “perception” of “actual” because the real issue is the identification of the table, judging whether it is a table or a bench, and thus “roughly” a table is a rock with a board on it. But I jump ahead I think; I’m going to read along. -

Antony Nickles

1.4kPerception is far more than just to say, what I see is "real", and that is it. The aftermath of perception is more complex, deep, rich and meaningful in human perception. — Corvus

Antony Nickles

1.4kPerception is far more than just to say, what I see is "real", and that is it. The aftermath of perception is more complex, deep, rich and meaningful in human perception. — Corvus

If we read on, perception is used as a straw man for any problems in the “aftermath of perception”, but “seeing” a table is to identify something as a table, which is judging whether something is a table, or, say, a bench (that we somehow mis-identify as a table) and not a matter “after” perception, but I’m getting ahead of the text. “…our senses are dumb… [they] do not tell us anything, true or false. -

Antony Nickles

1.4kBasically, I think that reality does exist objectively. — javi2541997

Antony Nickles

1.4kBasically, I think that reality does exist objectively. — javi2541997

There is a part in this (very small) lecture where he addresses “real” and “reality”. -

Antony Nickles

1.4kYes, I was somewhat concerned not to present Wittgenstein's view. — Banno

Antony Nickles

1.4kYes, I was somewhat concerned not to present Wittgenstein's view. — Banno

I’ll leave him out of it; only complicate things. One book at a time. But, come on…

“It is a matter of unpicking… fallacies… which leaves us, in a sense, just where we began.” P. 5

“…we may learn … a technique… for dissolving philosophical worries…” Id. -

javi2541997

7.2kIt is a very small lecture, indeed. I think the best I can do is to share the quote entirely. Yet, I read his points because he was quoted in another paper I read about 'Ontological Undecidability'. Here: https://www.friesian.com/undecd-1.htm#sect-9

javi2541997

7.2kIt is a very small lecture, indeed. I think the best I can do is to share the quote entirely. Yet, I read his points because he was quoted in another paper I read about 'Ontological Undecidability'. Here: https://www.friesian.com/undecd-1.htm#sect-9

It was noted above that the existence of hallucinations is an important datum for the manner in which we conceive of the relation between real and phenomenal. But we are still left without clear criteria to distinguish between veridical perception and hallucinatory perception. How do we know when there is and when there is not a real object? This weakness on the objective side of perception indicates that the relation between subject and object is not one that, even with undecidability, is ontologically symmetrical. The difficulties that have always resulted from this asymmetry merit our most serious consideration. For instance, Richard Fumerton believes that "an argument from the possibility of hallucination" proves that naive realism is wrong, meaning that, "we are never directly acquainted with the fact that a physical object exists..." Otherwise, Fumerton's argument turns on the same point as the argument given above, that a cause is only sufficient to its effect, that we conceive of perceptions as caused, and so that an evidently veridical perception can conceivably be caused by something other than the objects it seems to represent. In our experience we are, perhaps, directly acquainted with the facts concerning our mental states, but the possibility that experiences are hallucinations proves that we cannot be directly acquainted with the facts concerning physical objects that, beyond our reckoning, may or may not be causes of our experiences.

I am a bit lost in discerning between 'real' and 'reality', but if I am not wrong, the core of the two concepts depends on truth. Objects are the subject of our knowledge, and their reality depends on our perspective of the world, although they are plainly 'real'. So, while reality is a concept of ours, real is ontological. Agree? -

creativesoul

12.2kSupposing that we have them at all (see Davidson), do we perceive our world views or do we discover or construct them? — Banno

We adopt, discover, and construct them. They are both causes and effects/affect. We perceive their effects/affects. That's tangential to the topic though.

I'm just curious about the approach to direct/indirect perception. -

Corvus

4.8kIf we read on, perception is used as a straw man for any problems in the “aftermath of perception”, but “seeing” a table is to identify something as a table, which is judging whether something is a table, or, say, a bench (that we somehow mis-identify as a table) and not a matter “after” perception, but I’m getting ahead of the text. “…our senses are dumb… [they] do not tell us anything, true or false. — Antony Nickles

Corvus

4.8kIf we read on, perception is used as a straw man for any problems in the “aftermath of perception”, but “seeing” a table is to identify something as a table, which is judging whether something is a table, or, say, a bench (that we somehow mis-identify as a table) and not a matter “after” perception, but I’m getting ahead of the text. “…our senses are dumb… [they] do not tell us anything, true or false. — Antony Nickles

You need more than just identifying a table as a table in visual perception. What if the object you were seeing was a look-alike table, but actually it is a chair? Upon folding out the folded down back underneath the table, it works as a chair? Is it a chair or table?

In perception, there is far more going on than just identifying an object as an object i.e. reasoning, intuition, judgement and intentionality can get all involved, and for that they have to be sense data, which is the medium in the consciousness caused by the real object in the external world. Not the real objects themselves, because you cannot store the actual tables into your consciousness or memory. You would store the sense data of the table in your memory.

The realist's account on perception sounds too simple. Is there a point even asking what perception is? -

Antony Nickles

1.4k

Antony Nickles

1.4k

I don’t know what you are quoting; I was referring to Austin’s lecture, which is what we are reading. I thiink it would be getting ahead of ourselves to take into considerations other readings before we attempt our own or even have a clear view of what he is saying at way, as he is only collecting evidence and has not gotten to why the philosopher wants to have a generalized problem with everything we see all the time “already, from the very beginning” p. 8. -

javi2541997

7.2kI don’t know what you are quoting; I was referring to Austin’s lecture, which is what we are reading — Antony Nickles

javi2541997

7.2kI don’t know what you are quoting; I was referring to Austin’s lecture, which is what we are reading — Antony Nickles

I know this thread is about Austin, but when you mentioned me saying: There is a part in this (very small) lecture where he addresses 'real' and 'reality', (here) I thought you had a look at what I shared about Fumerton because that is what I debated with Frank mainly. He and I had a brief exchange on hallucination and how it could be related to Austin. I beg your pardon if I confused you for taking into considerations other readings. -

Fooloso4

6.2kYou need more than just identifying a table as a table in visual perception. — Corvus

Fooloso4

6.2kYou need more than just identifying a table as a table in visual perception. — Corvus

I think this is a good point. In the case of a table, and perhaps more clearly in the case of a pen or cigarette, what we see in not simply an object in passive perception, but something culturally and conceptually determined. In a culture without tables or pens or cigarettes what is seen is not a table or pen or cigarette. But neither is what is seen "sense data".

(40)If, to take a rather different case, a church were cunningly camouflaged so that it looked like a barn, how could any serious question be raised about what we see when we look at it ? We see, of course, a church that now looks like a barn.

I agree with Austin that what we see is not something immaterial, but I do not think it a matter of course that what we see is a church that looks like a barn. It is only when the camouflage is removed that what we see is a church. What it is and what we see are not the same. What we see is what it looks like to us. -

Ludwig V

2.5kI only discovered this thread to-day. Best thing that's happened to me in a long time. But I have read everything from the beginning. I lost my copy of Sense and Sensibilia in the distant past, but I've downloaded the pdf.

Ludwig V

2.5kI only discovered this thread to-day. Best thing that's happened to me in a long time. But I have read everything from the beginning. I lost my copy of Sense and Sensibilia in the distant past, but I've downloaded the pdf.

First, a general question. Everybody seems to be confident that they understand direct vs. indirect perception. I can sort of understand what is meant by indirect perception and why it is thought to be the appropriate way of looking at perception, as here:-

In perception, there is far more going on than just identifying an object as an object i.e. reasoning, intuition, judgement and intentionality can get all involved, and for that they have to be sense data, — Corvus

It would be reasonable to introduce a term like sense-data as a place-holder for whatever it is we decide we perceive directly. It's when you try to identify what the sense-data are that the trouble begins, for me, at least. The obvious candidates are either the signals sent to our brain by our nervous system or the events that trigger our nervous system to send a signal (light waves, sound waves, etc.) But those are nothing like what Russell or Ayer had in mind.

But my biggest puzzle is what would count as direct perception. Austin seems to me to begin to give an answer to that question by explaining what we mean by indirect perception. My only doubt about his argument is that perhaps it is unhelpful when we come to experimental psychology or neurology.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Does something make no sense because we don't agree, or do we not agree because it makes no sense.

- Sometimes, girls, work banter really is just harmless fun — and it’s all about common sense

- The Judeo-Christian Concept of the Soul Just doesn't make sense

- Did the movie SIXTH SENSE destroy the myth that perception is absolute reality?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum