-

Dermot Griffin

137I'd like to discuss this topic in 3 parts. The first is dedicated to the legacy of Thomism in the modern world according to two very different interpretations: One centered on the work of Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, a "Strict Observance" Thomist, and the other centered around the Lublin School of Thomism at the Catholic University of Lublin in Poland. I will compare the two and argue why Lublin Thomism, or "Polish Existential Thomism," has risen in popularity since John Paul II's era. The second part of this post will be dedicated to unraveling why Soren Kierkegaard is possibly one of the most important Protestant theologians to have ever lived and discuss his impact on non-Protestants. The third and final part will discuss how these positions are similar to Orthodox Christianity and ultimately conclude with what Catholic and Protestant thought are lacking in and that is an emphasis on mystical theology.

Dermot Griffin

137I'd like to discuss this topic in 3 parts. The first is dedicated to the legacy of Thomism in the modern world according to two very different interpretations: One centered on the work of Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, a "Strict Observance" Thomist, and the other centered around the Lublin School of Thomism at the Catholic University of Lublin in Poland. I will compare the two and argue why Lublin Thomism, or "Polish Existential Thomism," has risen in popularity since John Paul II's era. The second part of this post will be dedicated to unraveling why Soren Kierkegaard is possibly one of the most important Protestant theologians to have ever lived and discuss his impact on non-Protestants. The third and final part will discuss how these positions are similar to Orthodox Christianity and ultimately conclude with what Catholic and Protestant thought are lacking in and that is an emphasis on mystical theology.

The "Strict Observance" Thomism of Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange and the Phenomenological-Existential Method of the Lublin School

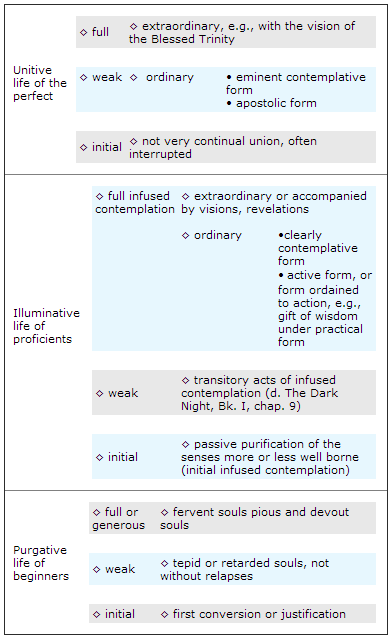

I tend to downplay Fr. Garrigou-Lagrange for a number of reasons. Firstly, Strict Observance Thomism is a hard, often literalist, reading of the Corpus Thomisticum, the works of St. Thomas Aquinas. Garrigou-Lagrange saw Thomism as a true "theory of everything" that could solve every problem imaginable; I generally don't like this approach because it is too limiting intellectually. However, his legacy of work is astonishing. His commentaries on the Summa Theologica are unbelievably insightful (The One God, Christ the Savior). His magnum opus which as influenced me greatly is his book The Three Ways of the Spiritual Life, published initially as The Three Ages of the Interior Life. Garrigou-Lagrange touches on a mystical theology, drawn from people like St. Augustine and St. John of the Cross. This diagram found in his book, to be read from the bottom up, is helpful in understanding his mysticism -

This follows the classic patristic model of purgation of the self (kenosis), illumination of the self (theoria), and the eventual divinization or sanctification of the self unto God (theosis). This classical paradigm has influenced just about every Christian intellectual, be it western or eastern. The Lublin School agrees with this format but differs in terms of methodology. While Garrigou-Lagrange read Aquinas as "hard" as he possibly could, Lublin Thomism seeks to use the philosophies of phenomenology and existentialism to better understand the human experience in terms of faith. Notable thinkers here are Mieczysław Albert Krąpiec, who is considered the founding figure of the Lublin School, and Karol Wojtyła, known to the world as John Paul II; This school of thought was found as a reaction to the rise of the Polish Communist Party and was seen as an attempt to combat Marxism. The major difference between a Garrigou-Lagrange and the Lublin Thomist's is the emphasis on personalism, a modern philosophy that asserts that the human person is a free responsible moral agent made in the image of God; Garrigou-Lagrange was almost always critical of modern philosophies. I think we should take Garrigou-Lagrange to heart; The outline of his mysticism is wonderful and very practical. However, the personalistic stance of Lublin Thomism is much more applicable to questions about everyday life.

The Impact of Kierkegaardian Existential Theology

Soren Kierkegaard is known to history as a melancholy Dane but a bright intellectual; John Paul II was known to have been an admirer of Kierkegaard, as his thought meshes well with Lublin Thomism. To breakdown his thought, man lives in a state of despair which is sin. When confronted with two moral extremes we experience anxiety, which according to him is our ability to feel total freedom. The aesthetic life is a life guided by pleasure; We rarely take into the account the consequences of our actions. The ethical life is a life guided by rational inquiry into what we do and say. This ultimately is followed by the religious life, taking a "leap of faith" into the hands of the Unknowable God. Jesus Christ is considered by Kierkegaard the ultimate paradox because of the idea that Christ is the God-Man, the connection between the physical and the spiritual. Kierkegaard meshes well with the Lublin School because of their focus on human experience while not falling into relativism. Kierkegaard constantly spoke of Christendom being without Christians because he felt many of the established churches fell short from "New Testament Christianity."

Holy Orthodoxy as an expression of New Testament Christianity

This leads me to discuss the spirituality and praxis of the Eastern Church. Orthodoxy is an ancient tradition that is older than the Tridentine Mass and Protestant services based upon that. The Divine Liturgies of the various Orthodox Churches as well as Eastern Catholic Churches have a much older feel. Culturally these churches do not like change at all. The practice of hesychasm, contemplative prayer using the Jesus Prayer ("Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner"), is the heart of Orthodox praxis. This practice grounded in the intellectual tradition of Palamism, the thought of St. Gregory Palamas, is a gateway into a mysticism that is not only practical but an expression of New Testament Christianity. Roman Catholics and Protestants don't need to do away with their traditions in order to integrate this into their spiritual life; The format of hesychasm follows the patristic model of mysticism that Fr. Garrigou-Lagrange attempts to model. In conclusion, the legacies of these great intellectual and theological traditions provide a route to unravel what New Testament Christianity really is all about.

-

T4YLOR

8I absolutely love this post. I myself come from the protestant tradition of Methodism. It is quite obvious that Christianity today is vastly different from what it was in the early church. I believe one of the most important aspects of Christianity is adherence to tradition. Something you had said that struck me in particular was,

T4YLOR

8I absolutely love this post. I myself come from the protestant tradition of Methodism. It is quite obvious that Christianity today is vastly different from what it was in the early church. I believe one of the most important aspects of Christianity is adherence to tradition. Something you had said that struck me in particular was,

Kierkegaard meshes well with the Lublin School because of their focus on human experience while not falling into relativism. — Dermot Griffin

When one does away with tradition, it makes them much more prone to falling into a state of religious relativism, which affects what they believe about essential doctrines. John Wesley saw the need for a more personal relationship between God and humans and thus started a movement that was founded upon the ideals of faith through practice (which gets to your points made about Orthodoxy). The problem that Methodism saw is that people were susceptible to falling from tradition because of the priority placed on religious experience and their neglect of scripture and tradition. It is sad to see that many people today call themselves Christians and yet are not even followers of Christ. I admire my Catholic and Orthodox brothers and sisters and, at times, envy them due to their unshakeable faith and rigorous practices.

Albert Outler coined a term known as the "Wesleyan Quadrilateral" that explains the importance of a synthesis between experience, reason, scripture, and tradition. I particularly like this system because it is similar to the checks and balances system that we see in the United States government. That way, not one aspect of the Christian faith can distort a Christian's perspective. -

Dermot Griffin

137

Dermot Griffin

137

I appreciate your reply. I am probably going to make a post on the use of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism as apologetical tools to argue for Christianity. I often think that fellow Christians see them as just different philosophical traditions or religions (especially Buddhism) and do not realize the worth they have as lens to view the Bible from. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI looked up Lublin Thomism, and from the overview page that came up:

Wayfarer

26.1kI looked up Lublin Thomism, and from the overview page that came up:

Saint Thomas presents a philosophy based on existence, which we may call “existentialism” (but we must avoid any confusion with the philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre in this regard). — Brief Overview of Lublin Thomism

That aspect of 'existentialism' appeals to me because of the understanding that 'being is an act'. About the only reading I've done in the area are some brief readings of Jacques Maritain but I believe he is also part of the same broad school of thought. I have been impressed by his essay, The Cultural Impact of Empiricism, because I have become convinced of the reality of universals and aspects of scholastic realism. I also realise that I have been very much influenced by Christian Platonism - I think it's a kind of inborn cultural archetype. Consequently some of the Catholic philosophers I've encountered are intuitively appealing, although I don't feel much drawn to the Church.

I often think that fellow Christians see them as just different philosophical traditions or religions (especially Buddhism) and do not realize the worth they have as lens to view the Bible from. — Dermot Griffin

I've been a student of Buddhism a lot of my adult life, even completing an MA in the subject, and participating in a discussion group for many years. I kept up the practice of sitting meditation as per Buddhist principles for many years, but fell out of the routine three years ago, and haven't gone back to it. I've become sceptical of Western Buddhism - that is, Buddhism as practiced and propogated in modern culture. And while I have considerable respect for the teaching and principles I don't feel as though I've been able to successfully integrate into them or with them. I did have some real epiphanies associated with meditation earlier in life, but then it's been like a 'seeds and weeds' scenario in the subsequent years. (I'm in a quandary about it, although I suppose internet forums aren't really a good medium to air such things.) -

Tom Storm

10.8kfell out of the routine three years ago, and haven't gone back to it. I've become sceptical of Western Buddhism - that is, Buddhism as practiced and propogated in modern culture. And while I have considerable respect for the teaching and principles I don't feel as though I've been able to successfully integrate into them or with them. I did have some real epiphanies associated with meditation earlier in life, but then it's been like a 'seeds and weeds' scenario in the subsequent years. (I'm in a quandary about it, although I suppose internet forums aren't really a good medium to air such things.) — Wayfarer

Tom Storm

10.8kfell out of the routine three years ago, and haven't gone back to it. I've become sceptical of Western Buddhism - that is, Buddhism as practiced and propogated in modern culture. And while I have considerable respect for the teaching and principles I don't feel as though I've been able to successfully integrate into them or with them. I did have some real epiphanies associated with meditation earlier in life, but then it's been like a 'seeds and weeds' scenario in the subsequent years. (I'm in a quandary about it, although I suppose internet forums aren't really a good medium to air such things.) — Wayfarer

This is very interesting and I have to say I feel for you. Has this change in focus been responsible for drawing you to some of the richer, earlier traditions of Christianity? I get that this is a hard topic, so feel free to move on. I think it would be interesting to understand more about your position on Buddhism - do you think this reflects personal factors, or is it perhaps something intrinsic to Westerners? I wonder if cultural fit is important in spiritual journeys - obviously the notion a higher awareness transcends culture, but the path along the way seems to be bound to it. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe thing which I'm really feeling the absence of right now is real spiritual assocation although I'm sure I'm not going to find it in churches. My quest for enlightenment started from the conviction that there really is enlightenment. That was influenced by the culture at the time, I came of age in the 1960's and it was in the air - the Beatles and Maharishi and the counter-cultural interest in spirituality. I pursued that (rather quixotic) interest through a late-entry degree in philosophy, comparative religion and anthropology. Through that I discovered an affinity for Christian mysticism (although also maintained an aversion to 'Churchianity'). But I will say, the more I learned about enlightenment in the sense depicted in the various schools of the philosophia perennis the more I came to see it was there in Christian culture also, if you know where to look for it and how to interpret it. Evelyn Underhill, Dean Inge and Meister Eckhardt were of interest. Also the 'Zen Catholic' movement of Thomas Merton and his successors. There's a small collection of books on Buddhist Christianity (like this one). I just wish there were an association or teacher - not an online one! - that I could associate with in that genre.

Wayfarer

26.1kThe thing which I'm really feeling the absence of right now is real spiritual assocation although I'm sure I'm not going to find it in churches. My quest for enlightenment started from the conviction that there really is enlightenment. That was influenced by the culture at the time, I came of age in the 1960's and it was in the air - the Beatles and Maharishi and the counter-cultural interest in spirituality. I pursued that (rather quixotic) interest through a late-entry degree in philosophy, comparative religion and anthropology. Through that I discovered an affinity for Christian mysticism (although also maintained an aversion to 'Churchianity'). But I will say, the more I learned about enlightenment in the sense depicted in the various schools of the philosophia perennis the more I came to see it was there in Christian culture also, if you know where to look for it and how to interpret it. Evelyn Underhill, Dean Inge and Meister Eckhardt were of interest. Also the 'Zen Catholic' movement of Thomas Merton and his successors. There's a small collection of books on Buddhist Christianity (like this one). I just wish there were an association or teacher - not an online one! - that I could associate with in that genre. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

The third and final part will discuss how these positions are similar to Orthodox Christianity and ultimately conclude with what Catholic and Protestant thought are lacking in and that is an emphasis on mystical theology.

What do you mean by "mystical theology?" I find this to be a tricky term. Is mysticism just "experience of God?" Something like "knowing God the way a biographer/historian knows a person" (theology) versus "how their spouse knows that person," (personal/mystical)? This was Jean Gerson's expansive view in the 14th century, one used by some modern scholars, e.g. Harmless.

Or is mysticism about ecstasies, peak experiences, and visions, as William James would have it?

Or is this the "mystical theology," of Pseudo Dionysus (Saint Denis), an apophatic revelation of the "Divine Nothingness?"

It seems to me like the mystical tradition is generally much weaker in Protestantism. When it does manifest, it is much more often as more concrete, supernatural experiences: exorcisms, healing, visions, etc. I tend to be skeptical of these, both because of the historical ways they have been revealed to be hoaxes and because of my personal experiences with people who seem to be more living out a sort of self-serving fantasy life for themselves in this way, although I'm sure this isn't always the case.

However, the Catholic tradition still seems to have a fairly robust concept of mysticism. You have guys like Thomas Merton, James Finley, and of course the active orders of contemplative monks and nuns who still attract new novices.

It isn't always strong in individual churches, but it seems to be a decently strong undercurrent in the tradition. The communal praying of the Rosary is itself the sort of thing that is common in mystically oriented traditions, and I see the even at my local church. Although, only in the cathedrals of Latin America (Quito in particular) and Rome have I seen people in apparent ecstasies before the altars.

The Orthodox tradition I am less personally familiar with. It does seem to have a large focus on mysticism, perhaps more than the Catholic tradition, which has made room for a great deal of rationalism (Saint Thomas's "two winged bird" and all. But then again, the Orthodox Churches also seem to get more tied up in nationalism and performative tradition, particularly in Russia.

The Philokalia does have more stuff focused on mysticism than a Catholic reader might, but the Catholic tradition will still have Augustine's beatific vision, Pseudo Dionysus (a well spring for both, along with Gregory of Nysa), Saint Bonaventure and the vision of Saint Francis and the Seraphim, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, or Hildegard.

Apparently, in terms of tradition, the Oriental Churches and the Eastern Catholic Churches, e.g. the Chaldean Church, have the closest liturgy and worship setting to the early church. A good deal dates to the 4th century. I find it interesting how some of these had an easier time rejoining the Roman Catholic church than the more similar Eastern Orthodox churches in light of that. But they've kept their traditions despite the merger. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kBTW, the promise of mystical union with the divine seems to be a major part of the "Good News," that is neglected in contemporary accounts of the Gospel. Instead, Christianity is reduced to a story about how one avoids punishment and gains reward. Christianity as a path to freedom — freedom over circumstance, desire, and instinct — the sort of unification of the will Plato and Hegel talk about, is particularly neglected.

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kBTW, the promise of mystical union with the divine seems to be a major part of the "Good News," that is neglected in contemporary accounts of the Gospel. Instead, Christianity is reduced to a story about how one avoids punishment and gains reward. Christianity as a path to freedom — freedom over circumstance, desire, and instinct — the sort of unification of the will Plato and Hegel talk about, is particularly neglected.

As Saint Athanasius famously put it (quoting Saint Irenenius): "God became man that man might become God."

This isn't an elevation of man, but rather a transformation and union. Saint Paul stalks about "putting on the new man." Christ talks about being "reborn." The result is Christ as a bridge to the Divine Nature, through the Spirit. Saint Paul, Saint John, and Saint Peter all talk about "God living in us," "living in God," "Christ living in us," "I must decrease and Christ must increase," etc. We hear of living in the "fullness (pleroma) of God."

I also tend to agree with Tilich that competition with Islam (and later the Reformation) wounded the universality of Christianity. It became "one religion among many," as opposed to a universal, non-religion. The Patristics' sense of Christ as Logos had it that all knowledge was ultimately grounded in the divine. It was so easy for them to assimilate Platonism and Aristotle. The Logos was present in all cultures and religions, and all men craved the "true good," the "real truth." This sort of universalist self-confidence has been badly damaged though. You still see it in later figures though, Erasmus, Cusa, Boheme, Zwingli, Hegel, etc.

Thomism is probably a place where that sort of sentiment survives. -

Leontiskos

5.6kI've become sceptical of Western Buddhism - that is, Buddhism as practiced and propogated in modern culture. And while I have considerable respect for the teaching and principles I don't feel as though I've been able to successfully integrate into them or with them. I did have some real epiphanies associated with meditation earlier in life, but then it's been like a 'seeds and weeds' scenario in the subsequent years. — Wayfarer

Leontiskos

5.6kI've become sceptical of Western Buddhism - that is, Buddhism as practiced and propogated in modern culture. And while I have considerable respect for the teaching and principles I don't feel as though I've been able to successfully integrate into them or with them. I did have some real epiphanies associated with meditation earlier in life, but then it's been like a 'seeds and weeds' scenario in the subsequent years. — Wayfarer

Same here.

I get the sense that Buddhism is parasitic on Hinduism, and that trying to attach oneself to Buddhism without the benefit of Hindu culture is something of a non-starter. Similarly, I find interreligious dialogue between Catholicism and Hinduism to be more apropos and compelling than interreligious dialogue between Catholicism and Buddhism. Much like Protestantism, there is something incomplete about Buddhism. It is a religion working from a borrowed culture, and one which is founded on a critique of the more comprehensive religion which is properly attached to that borrowed culture. In both the Buddhist and Protestant cases there is the implicit claim that the cultural divorce is a feature and not a bug, and that's a rather difficult subject to query, but in the end I'm not so sure. I think religion and culture must ultimately go together, and that all attempts to indefinitely separate them are unrealistic.

What follows is that Buddhism and Protestantism do not transplant well. They do not possess the wherewithal to endure a foreign environment without becoming subsumed by it. Or if they do manage to survive, they do not possess the resources to produce and sustain a robust culture of their own. Thus such movements are short-lived on foreign soil.

...Also, in general I am wary of religions started by a single individual (e.g. Buddhism, Islam, Protestantism). Jesus is the exception if we accept the premise that he is divine, although we could also argue over whether he was, strictly speaking, a founder. There is something more organic, comprehensive, and compelling about religions like Hinduism, or Judaism, or even Taoism. But also more messy and unwieldy.

I also realise that I have been very much influenced by Christian Platonism - I think it's a kind of inborn cultural archetype. — Wayfarer

There seem to be a growing number of agnostic intellectuals who favor Christian culture and a Christian worldview, but who remain a step removed from Christian belief. Roger Scruton, Douglas Murray, and Tom Holland come immediately to mind. Part of this seems to be a backlash against the dull iconoclasm of the New Atheism, part of it a response to Marxist ideologies, but a lot of it seems to be a legitimate appreciation of the Christian patrimony and inheritance. This is all rather interesting to me, because Joseph Ratzinger often argued precisely in favor of such a move ("veluti si Deus daretur"). I always found the argument awkward, but apparently it has some purchase. Supposing religion and culture are inextricably linked, it makes sense that some would defend a religion for the sake of a culture.

I just wish there were an association or teacher - not an online one! - that I could associate with in that genre. — Wayfarer

This strikes me as a ubiquitous and perennial difficulty, namely that we are bound by our geography. The ideal of a strong 'guru' figure must often be foregone on account of this. -

Leontiskos

5.6k- Good post :up:

Leontiskos

5.6k- Good post :up:

This sort of universalist self-confidence has been badly damaged though. You still see it in later figures though, Erasmus, Cusa, Boheme, Zwingli, Hegel, etc. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, but I think Islam and Protestantism were just precursors to the inevitable pluralistic religious setting we now find ourselves in in the West. Presumably there is a natural ebb and flow between polytheism and monotheism over the millenia, and now the information age has shifted us back towards a more polytheistic orientation. What was once a cultural-religious whole has now become increasingly fractured. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIt seems to me like the mystical tradition is generally much weaker in Protestantism. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Wayfarer

26.1kIt seems to me like the mystical tradition is generally much weaker in Protestantism. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Jacob Böhme being an exception, although subject to severe criticism from the pulpit, but a big influence on German romantics.

the promise of mystical union with the divine seems to be a major part of the "Good News," that is neglected in contemporary accounts of the Gospel. Instead, Christianity is reduced to a story about how one avoids punishment and gains reward. Christianity as a path to freedom — freedom over circumstance, desire, and instinct — the sort of unification of the will Plato and Hegel talk about, is particularly neglected. — Count Timothy von Icarus

:100: There was no sense of that dimension in the Christian teachings I received in childhood. It was very much learn by rote and follow the rules. That leads to the dessicated social religion that Christianity has become - 'belief without evidence' as it's usually described here. And that is because so much of the symbolism is derived from the 'spiritual ascent' and only makes sense in relation to that. Now that I understand that, I'm re-considering!

(I've often remarked that the whole purpose of today's culture is to accomodate the human condition, to make it as comfortable as possible, whereas the aim of spiritual culture is to transcend it. It's a hard truth.)

That second image in the OP is associated with The Ladder of Divine Ascent. The article contains a translation, which I shall read.

I find interreligious dialogue between Catholicism and Hinduism to be more apropos and compelling than interreligious dialogue between Catholicism and Buddhism — Leontiskos

Oh, I don't know about that. I mentioned Zen Catholicism, and I've seen some estimable teachers from that school. There are many points of convergence. I also saw the Venerable Bede Griffith, not long before his death - very frail but still vital and serene - a Catholic monk who had settled in an Indian ashram.

Venerable Father Bede Griffith

What follows is that Buddhism and Protestantism do not transplant well — Leontiskos

Buddhism has been a very successful cultural export. From its origins in Maghada in Northern India, it spread along the Silk Road to become a major world religion, indeed the principle religion of Eastern culture.

I've absorbed some crucial elements from Buddhism - not beliefs so much as cognitive skills - which will always stay with me. Whatever doubts I harbor are not about it, but about me. -

J

2.4kThat leads to the dessicated social religion that Christianity has become - 'belief without evidence' as it's usually described here. — Wayfarer

J

2.4kThat leads to the dessicated social religion that Christianity has become - 'belief without evidence' as it's usually described here. — Wayfarer

I think the "dessicated social religion" part is very true, provided you're talking about mainstream U.S. Christian denominations -- perhaps not the best sample.

"Belief without evidence" is trickier. There's all kinds of evidence for the existence of God and even the divinity of Jesus, but none of it is rock solid. As in so many areas, we're left with beliefs that fall far short of certainty, but are hardly as bereft as "belief without evidence" sounds. In my opinion (and experience), a direct encounter with the mystical is extremely powerful evidence in support of theism. It isn't self-validating, but the "God hypothesis" can be compared critically with other explanations for the experience, and I can decide that the other explanations aren't as plausible -- as indeed I have. -

wonderer1

2.4kIn my opinion (and experience), a direct encounter with the mystical is extremely powerful evidence in support of theism. — J

wonderer1

2.4kIn my opinion (and experience), a direct encounter with the mystical is extremely powerful evidence in support of theism. — J

Have you ever tried LSD, as a basis for comparison of altered states that you can experience?

I can certainly understand mystical states of mind as having an intensity that can be surprising, and how people can easily be inclined to think a non-mundane explanation is needed. However, "powerful evidence"? -

J

2.4kHave you ever tried LSD? — wonderer1

J

2.4kHave you ever tried LSD? — wonderer1

Have I ever! Don't get me started . . . :starstruck:

I don't mean to make this just about me, but the (non-LSD) experience I had, some 35 years ago now, has stubbornly resisted being reduced to psychological categories. I certainly tried, as did most of my concerned friends. The main reason I call it strong evidence is that it changed my life in a way that was immediate, profound, and long-lasting, and made sense of all the previously senseless God-talk I'd heard. I think William James has the best descriptions of this sort of thing in Varieties of Religious Experience, but there are many Eastern accounts as well.

Could I be wrong? Sure -- no certainty, as I said. But I'm satisfied to have found the most likely explanation. -

Wayfarer

26.1k"Belief without evidence" is trickier. There's all kinds of evidence for the existence of God and even the divinity of Jesus, but none of it is rock solid. As in so many areas, we're left with beliefs that fall far short of certainty, but are hardly as bereft as "belief without evidence" sounds. In my opinion (and experience), a direct encounter with the mystical is extremely powerful evidence in support of theism. — J

Wayfarer

26.1k"Belief without evidence" is trickier. There's all kinds of evidence for the existence of God and even the divinity of Jesus, but none of it is rock solid. As in so many areas, we're left with beliefs that fall far short of certainty, but are hardly as bereft as "belief without evidence" sounds. In my opinion (and experience), a direct encounter with the mystical is extremely powerful evidence in support of theism. — J

Totally with you on all that. But the accusation of belief without evidence is often raised on this forum whenever any vaguely religious sentiment is expressed. In the context of today's culture, science is implicitly understood as the arbiter of what should be taken seriously, so to argue for anything deemed metaphysical or mystical is generally relegated to the domain of faith - it may be edifying, but you have no way of showing that it's true. Part of this is that, not only Biblical texts, but the literature of all the traditions of the sacred, are presumed to lack any evidentiary value, because, for instance, 'all the religions make competing claims to the one truth, how could any of them be right?' (I get that a lot.)

Have you ever tried LSD? — wonderer1

Back in the day. I'm a sixties person and it was around then, in fact when I first tripped, it hadn't been banned yet. It can be (although not always is) like a window to another dimension of existence. The memories I retain are a sense of rapture at the extraordinary beauty of natural things, some vivid hallucinatory experiences, and a sense of 'why isn't life always like this?' -

Wayfarer

26.1kI think Philosophy of Religion ought to accomodate it. I try to maintain a 'philosophy of religion' on the forum, as far as possible. It's a different orientation to evangalism or proselytizing (although there are some who will always take it that way.) But I'll log your suggestion with the Forum Admin as there is some background work going on on refinements.

Wayfarer

26.1kI think Philosophy of Religion ought to accomodate it. I try to maintain a 'philosophy of religion' on the forum, as far as possible. It's a different orientation to evangalism or proselytizing (although there are some who will always take it that way.) But I'll log your suggestion with the Forum Admin as there is some background work going on on refinements. -

J

2.4kScience is implicitly understood as the arbiter of what should be taken seriously — Wayfarer

J

2.4kScience is implicitly understood as the arbiter of what should be taken seriously — Wayfarer

I don’t know if you’ve read Walker Percy. He makes an interesting distinction between “knowledge” and “news.” Knowledge would be the sort of thing that, broadly, science investigates. News, on the other hand, is information that you can’t deduce or discover for yourself; someone has to tell you. This would include religious revelation, for Percy. And he says that the “credentials of the news-bearer” are important evidence for whether to trust the news.

This may be too black-and-white, but I see what he’s getting at and I think it’s a valuable insight. I wonder what Aquinas would say, getting back to the OP. He made a distinction between natural and revealed religion, didn’t he? And I'm sure Kierkegaard, that champion of subjectivity, would agree. -

Wayfarer

26.1kWell, reading about Lublin Thomism, on Dermot Griffin's suggestion, I came across an interesting term in religious literature - 'gnoseology' (rather a peculiar sounding word, but never mind.) The thrust of it is that it's to do with 'gnosis' - not 'gnosis' in the sense of 'gnosticism' (which is heretical) but simply as 'higher knowledge'. If you look it up in the dictionary, it basically says it's an alternative for 'epistemology', but the etymological root, gn-, signifies its affiliation with gnosis (which is also found in Sanskrit languages as 'jnana'.) Apparently it is part of the curriculum in scholastic philosophy. I have a rather interesting book on Orthodox Christianity in which there is also some discussion of gnosis as 'higher knowledge' (and carefully distinguished from gnosticism per se).

Wayfarer

26.1kWell, reading about Lublin Thomism, on Dermot Griffin's suggestion, I came across an interesting term in religious literature - 'gnoseology' (rather a peculiar sounding word, but never mind.) The thrust of it is that it's to do with 'gnosis' - not 'gnosis' in the sense of 'gnosticism' (which is heretical) but simply as 'higher knowledge'. If you look it up in the dictionary, it basically says it's an alternative for 'epistemology', but the etymological root, gn-, signifies its affiliation with gnosis (which is also found in Sanskrit languages as 'jnana'.) Apparently it is part of the curriculum in scholastic philosophy. I have a rather interesting book on Orthodox Christianity in which there is also some discussion of gnosis as 'higher knowledge' (and carefully distinguished from gnosticism per se).

Consider this passage from Buddhist scholar, Edward Conze:

The "perennial philosophy" is ...defined as a doctrine which holds [1] that as far as worthwhile knowledge is concerned not all men are equal, but that there is a hierarchy of persons, some of whom, through what they are, can know much more than others; [2] that there is a hierarchy also of the levels of reality, some of which are more "real," because more exalted than others; and [3] that the wise have found a "wisdom" which is true, although it has no "empirical" basis in observations which can be made by everyone and everybody; and that in fact there is a rare and unordinary faculty in some of us by which we can attain direct contact with actual reality--through the Prajñāpāramitā of the Buddhists, the logos of Parmenides, the sophia of Aristotle and others, Spinoza's amor dei intellectualis, Hegel's Vernunft, and so on; and [4] that true teaching is based on an authority which legitimizes itself by the exemplary life and charismatic quality of its exponents.

This maps quite well against the table that is provided in the OP.

My belief is that there is a real qualitative dimension, the vertical axis - which I think is the minimum possible requirement for a spiritual philosophy. But this is non-PC in secular culture, which is a flatland as far as values are concerned: every individual is his or her own arbiter of value, and any claims to 'higher knowledge' amount to authoritarianism and dogma. -

wonderer1

2.4kThe memories I retain are a sense of rapture at the extraordinary beauty of natural things, some vivid hallucinatory experiences, and a sense of 'why isn't life always like this?' — Wayfarer

wonderer1

2.4kThe memories I retain are a sense of rapture at the extraordinary beauty of natural things, some vivid hallucinatory experiences, and a sense of 'why isn't life always like this?' — Wayfarer

For me it was the early 80s. I didn't have vivid hallucinations, although people I tripped with did. (I suspect I may be towards the aphantasic end of a aphantasia-hyperphantasia spectrum.)

But yes, the overwhelming beauty of everything was wonderful to experience. -

Wayfarer

26.1kA new word! (I'm inclined to start a thread on 'philosophies of consciousness' - the link between psychedelic experiences and Eastern philosophy. Won't clutter up this one.)

Wayfarer

26.1kA new word! (I'm inclined to start a thread on 'philosophies of consciousness' - the link between psychedelic experiences and Eastern philosophy. Won't clutter up this one.) -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kBut the accusation of belief without evidence is often raised on this forum whenever any vaguely religious sentiment is expressed. — Wayfarer

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kBut the accusation of belief without evidence is often raised on this forum whenever any vaguely religious sentiment is expressed. — Wayfarer

Not only that, but the meaning of "evidence" to some here has been so narrowed down by empirical principles, that it could only mean something which appears directly through an individual's sensations. This effectively renders "evidence" as completely subjective which is the exact opposite to what these people intend.

This is the result of removing the requirement of a logical relation between the thing which is evidence, and the thing which it is evidence of. And this logical relation is the essence of "evidence". The empiricist attempt to remove this necessary logical relation, to make "evidence" an empirically based concept would render the concept completely subjective and worthless. -

Wayfarer

26.1kNot only that, but the meaning of "evidence" to some here has been so narrowed down by empirical principles, that it could only mean something which appears directly through an individual's sensations. — Metaphysician Undercover

Wayfarer

26.1kNot only that, but the meaning of "evidence" to some here has been so narrowed down by empirical principles, that it could only mean something which appears directly through an individual's sensations. — Metaphysician Undercover

And validated in peer-reviewed science journals!

I've often reflected, when Dawkins waves his hands around and says 'but where is the evidence??' that any believer could simply say 'you're standing in it!' -

J

2.4kT. M. Scanlon is good on this:

J

2.4kT. M. Scanlon is good on this:

"Accepting science as a way of understanding the natural world entails rejecting claims about this world that are incompatible with science, such as claims about witches and spirits. But accepting a scientific view of the natural world does not mean accepting the view that the only meaningful statements with determinate truth values are statements about the natural world." (from Being Realistic About Reasons, 2011)

Also this, from Thomas Nagel:

"It is not one of the claims of natural science that natural science contains all the truths there are." (from Analytic Philosophy and Human Life, 2023)

These philosophers are drawing attention to one of the most common misunderstandings of what science does. There is no "completeness theorem" for truths either entailed or revealed by science -- only scientism would try to make such a claim. -

Leontiskos

5.6kI don’t know if you’ve read Walker Percy. He makes an interesting distinction between “knowledge” and “news.” Knowledge would be the sort of thing that, broadly, science investigates. News, on the other hand, is information that you can’t deduce or discover for yourself; someone has to tell you. This would include religious revelation, for Percy. And he says that the “credentials of the news-bearer” are important evidence for whether to trust the news.

Leontiskos

5.6kI don’t know if you’ve read Walker Percy. He makes an interesting distinction between “knowledge” and “news.” Knowledge would be the sort of thing that, broadly, science investigates. News, on the other hand, is information that you can’t deduce or discover for yourself; someone has to tell you. This would include religious revelation, for Percy. And he says that the “credentials of the news-bearer” are important evidence for whether to trust the news.

This may be too black-and-white, but I see what he’s getting at and I think it’s a valuable insight. I wonder what Aquinas would say, getting back to the OP. He made a distinction between natural and revealed religion, didn’t he? And I'm sure Kierkegaard, that champion of subjectivity, would agree. — J

I really enjoy Walker Percy, but it's been a few years since I've read him. Recently I have been reading Pascal, Kierkegaard, and Johann Georg Hamann: three nice counterbalances to the rationalism of this forum. Here is a characteristically polemical utterance from Hamann, haha:

Christianity believes, that is to say, not in the doctrines of philosophy, which are nothing

but an alphabetic scribbling of human speculation, and subject to the fluctuating cycles of

moon and fashion! – not in images and the worship of images! – not in the worship of

animals and heroes! – not in symbolic elements and passwords or in some black figures

obscurely painted by the invisible hand on the white wall! – not in Pythagorean-Platonic

numbers!!! – not in the passing shadows of actions and ceremonies that will not remain

and not endure, which are thought to possess a secret power and inexplicable magic! – –

not in any laws, which must be followed even without faith, as the theorist somewhere

says, notwithstanding his Epicurean-Stoic hairsplitting about faith and knowledge! – –

No, Christianity knows of and recognizes no other bonds of faith than the sure prophetic

Word as recorded in the most ancient documents of the human race and in the holy scrip-

tures of authentic Judaism, without Samaritan segregation and apocryphal Mishnah. — After Enlightenment: Hamann as Post-Secular Visionary, by John R. Betz, p. 283

(The context here is a metacritical response to Moses Mendelssohn’s Jerusalem.)

I wonder what Aquinas would say, getting back to the OP. He made a distinction between natural and revealed religion, didn’t he? — J

Aquinas is more or less in agreement with Percy. Here is the body of an article on whether theology (sacred doctrine) is a matter of argument:

As other sciences do not argue in proof of their principles, but argue from their principles to demonstrate other truths in these sciences: so [sacred doctrine] does not argue in proof of its principles, which are the articles of faith, but from them it goes on to prove something else [...] . However, it is to be borne in mind, in regard to the philosophical sciences, that the inferior sciences neither prove their principles nor dispute with those who deny them, but leave this to a higher science; whereas the highest of them, viz. metaphysics, can dispute with one who denies its principles, if only the opponent will make some concession; but if he concede nothing, it can have no dispute with him, though it can answer his objections. Hence Sacred Scripture, since it has no science above itself, can dispute with one who denies its principles only if the opponent admits some at least of the truths obtained through divine revelation; thus we can argue with heretics from texts in Holy Writ, and against those who deny one article of faith, we can argue from another. If our opponent believes nothing of divine revelation, there is no longer any means of proving the articles of faith by reasoning, but only of answering his objections — if he has any — against faith. Since faith rests upon infallible truth, and since the contrary of a truth can never be demonstrated, it is clear that the arguments brought against faith cannot be demonstrations, but are difficulties that can be answered. — Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, Ia, Q. 1, A. 8

For Aquinas an article of faith cannot be demonstrated or refuted by natural, philosophical reasoning. Thus someone who denies an article of faith cannot be argued into the position, even though their positive objections can be met. The difference between Aquinas and Percy would seem to be that, for Aquinas, revelation ("news") is not restricted to things that are in-principle indemonstrable. For example, Aquinas believes that "the universe had a beginning" is a revealed truth. Aristotle argues from natural reason that the universe had no beginning, and so Aquinas sets himself to meeting and nullifying Aristotle's arguments.

Aquinas also makes a distinction between natural and revealed religion, but his distinction between natural and revealed knowledge seems more appropriate. I tend to agree with him that, in the broad sense, 'religion' is not primarily a matter of knowledge. -

Leontiskos

5.6k- A common thread in all of these positions is the idea that knowledge is not merely cerebral and abstract (e.g. the Hebrew, Indian, Platonic, and Christian traditions). If you consider our modern landscape from that point of view it is highly idiosyncratic, and in fact there is something very odd about the way we conceive of knowledge. If someone from the past visited our time they would be utterly baffled until we showed them the historical genealogy of how we got here.

Leontiskos

5.6k- A common thread in all of these positions is the idea that knowledge is not merely cerebral and abstract (e.g. the Hebrew, Indian, Platonic, and Christian traditions). If you consider our modern landscape from that point of view it is highly idiosyncratic, and in fact there is something very odd about the way we conceive of knowledge. If someone from the past visited our time they would be utterly baffled until we showed them the historical genealogy of how we got here. -

Wayfarer

26.1kA common thread in all of these positions is the idea that knowledge is not merely cerebral and abstract (e.g. the Hebrew, Indian, Platonic, and Christian traditions — Leontiskos

Wayfarer

26.1kA common thread in all of these positions is the idea that knowledge is not merely cerebral and abstract (e.g. the Hebrew, Indian, Platonic, and Christian traditions — Leontiskos

I don't know if it's true of those traditions, but what has been handed down. The sapiential and practical sides of the disciplines have been ignored or treated as secondary, whereas in reality, that is the way that the ideas 'come to life'. Have a read of Karen Armstrong's metaphysical mistake. -

J

2.4kIt's also interesting to see the distinction Aquinas makes between "faith" and "articles of faith." If I'm reading him rightly, he says that objections to faith itself can be replied to argumentatively -- they are "difficulties that can be answered." Whereas any particular article of faith is precisely that -- a belief held on faith -- and the only way to reply to the doubter here relies on first finding an agreement that faith is even possible, and then pointing out inconsistencies in the doubter's position using other articles of faith. This is quite subtle. Does it generalize to other overarching world-views? I think it might, though Aquinas seems to be saying that "metaphysics" is in a unique position in this regard. But wouldn't scientism, for instance, also be able to speak about a similar distinction between "whether scientific knowledge is possible" and "the truths of science"? No one who denied the former could be convinced by the latter. But once scientific knowledge is granted, the specific truths -- the articles of faith, by analogy -- can be argued pro and con, using some truths to demonstrate or refute others.

J

2.4kIt's also interesting to see the distinction Aquinas makes between "faith" and "articles of faith." If I'm reading him rightly, he says that objections to faith itself can be replied to argumentatively -- they are "difficulties that can be answered." Whereas any particular article of faith is precisely that -- a belief held on faith -- and the only way to reply to the doubter here relies on first finding an agreement that faith is even possible, and then pointing out inconsistencies in the doubter's position using other articles of faith. This is quite subtle. Does it generalize to other overarching world-views? I think it might, though Aquinas seems to be saying that "metaphysics" is in a unique position in this regard. But wouldn't scientism, for instance, also be able to speak about a similar distinction between "whether scientific knowledge is possible" and "the truths of science"? No one who denied the former could be convinced by the latter. But once scientific knowledge is granted, the specific truths -- the articles of faith, by analogy -- can be argued pro and con, using some truths to demonstrate or refute others.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum