-

Wayfarer

26.1kIt seems obvious to me that there is no duck or rabbit until a mind observes the drawing and attaches meaning to it. This then leads me to think there is no information in a string of 1's and 0's unless a mind attaches meaning to the string of digits. For anyone who thinks information can exist independent of minds, where am I going wrong? IS there a duck or rabbit even when no one is looking at the picture? How does that work? — RogueAI

Wayfarer

26.1kIt seems obvious to me that there is no duck or rabbit until a mind observes the drawing and attaches meaning to it. This then leads me to think there is no information in a string of 1's and 0's unless a mind attaches meaning to the string of digits. For anyone who thinks information can exist independent of minds, where am I going wrong? IS there a duck or rabbit even when no one is looking at the picture? How does that work? — RogueAI

Have another look at Mind and the Cosmic Order. It is a book that has quite a lot to say about just this point. -

jgill

4k↪jgill

jgill

4k↪jgill

Wasn't there a gallery of your images on the site somewhere? I'd like to link it. — Banno

There are a few Here, and you can see what the math looks like.Look at my icon carefully. I could not have planned it and then created the necessary math, in my wildest dreams. — jgill

What are the axes of your drawing? — wonderer1

Like the standard Euclidean plane. Vertical (imaginary) axis in center and horizontal (real) axis across the middle. Sometimes I shift my focus to a small section of the complex plane. I did this to isolate and magnify my Quantum Bug icon. -

JuanZu

382When I think about emergentism, a lot of questions always arise (and of course I don't ask to be answered, since they are a bit rhetorical): When we say that something emerges from a physical thing, do we say that what emerges is also physical? And why do we say it is physical? Is it because they share some property? Is there any consensus on the definition of this property? Is it because they share constituent parts? Is it because the relationships and laws that govern these constituent parts explain the characteristics and properties of that which emerges? If emergentism tells us that new properties arise from its constituent parts, are the properties of the parts preserved in the new reality that emerges? Or are the properties lost? If the property is "being physical," wouldn't it be necessary to determine how that physical property is repeated and persists in the reality that supposedly emerges?

JuanZu

382When I think about emergentism, a lot of questions always arise (and of course I don't ask to be answered, since they are a bit rhetorical): When we say that something emerges from a physical thing, do we say that what emerges is also physical? And why do we say it is physical? Is it because they share some property? Is there any consensus on the definition of this property? Is it because they share constituent parts? Is it because the relationships and laws that govern these constituent parts explain the characteristics and properties of that which emerges? If emergentism tells us that new properties arise from its constituent parts, are the properties of the parts preserved in the new reality that emerges? Or are the properties lost? If the property is "being physical," wouldn't it be necessary to determine how that physical property is repeated and persists in the reality that supposedly emerges?

One can say that a citizen is composed of cells, but it is difficult to say that cells can be fellow citizens of each other. That seems like a categorical error. I think that emergentism gives an explanatory power to composition that it really does not have and that it constantly proves not to have as soon as we try to explain an increasingly larger whole from the parts. Thus falling into constant fallacies of division and composition. What remains in doubt is that we are actually talking about a whole in which each of its parts share a common property that, however, seems too specific and that can be applied less and less as we increase the focus to see a larger reality and greater content. And not only that, but the rule of unidirectional construction from the smallest to the largest is called into question. This is why I am not a substantialist (physical substance monism in this case) but instead advocate insubstantial pluralism.

There is the architectural metaphor. It tells us that there are building bricks from which structures and objects such as buildings are formed. But when I ask myself what are the building bricks of, say, computer language, ethical and moral values, mathematics and many other things (that at first do not seem physical to us) I feel like we are talking about how a joined bricks of a building explain the functions of the company that operates in that building. -

Wayfarer

26.1kinsubstantial pluralism. — JuanZu

Wayfarer

26.1kinsubstantial pluralism. — JuanZu

That's new to me!

Fossils are a good example. Did they just happen to form, or are they present because they have a material past?

I believe many things about the past -- the before now -- which are about the physical world. So I figure that must be physical, even if not present. (That dodoes existed, for instance) — Moliere

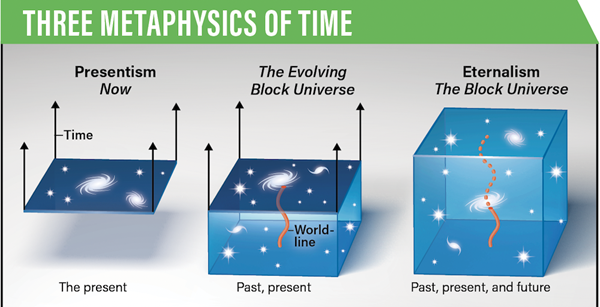

The philosophy I'm interested in recognises the empirical reality of past events, the pre-history of life before man and so on. But the reality that is imputed to them, is still imputed by an observing mind - yours, mine and whomever else considers the matter. The question is, is temporarility itself truly independent of any observing mind? And if the answer is yes, according to what scale or perspective is it so? Time - the measurement of duration - seems to me to depend on scale or perspective, and that is what it provided by the observing mind. None of which is to deny the reality of the fossil record. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

If the problem with explaining apparently emergent phenomena is just that you need a "lot more computational capabilities," then what you have is merely 'weak emergence,' and reduction still works. However, I don't think appeals to mind boggling complexity do anything to deal with the conceptual problem of how it is that we keep adding functions to some computation and then, at some indefinite point, our computation begins having first person subjective experiences (the plausibility problem).

Relevant to this first problem would be the argument that the information carrying capacity of all baryonic matter in the visible universe appears to be inadequate for computing even simple forms of life. If these sorts of arguments bear out, then the problem can't be resolved by more efficient computational methods.

The other problem with "weak emergence only," views (essentially the reductionist view) is their plausibility given problems related to the most basic phenomena we study. The problems with proposed instances of emergence vis-á-vis quantum mechanics itself, spacetime itself, holographic universe conceptions, molecular structure, etc. don't seem resolvable simply through greater computational power (see the quote below).

Your post seems to blend two ideas though. That our conceptual framework is fundementally lacking, and that we simply lack computational power adequate to "brute force," our way through these issues. I would just ask if these are the same position vis-á-vis emergence?

With the former view, I do think it's quite fair to ask if superveniance and thus "emergence" are even framed in the right terms, using the right categories. This is in line with process-based critiques of the entire problem, that it rests on bad assumptions baked into science that go back as far as Parmenides. The "lack of computational power," explanation seems like a different sort of explanation.

From the SEP article on emergence:

A striking feature of quantum mechanics is known as “quantum entanglement”. When two (or more) quantum particles or systems interact in certain ways and are then (even space-like) separated, their measurable features (e.g., position and momentum) will correlate in ways that cannot be accounted for in terms of “pure” quantum states of each particle or system separately. In other words, the two need to be thought of as a coupled system, having certain features which are in no sense a compositional or other resultant of individual states of the system’s components (see Silberstein & McGeever 1999 and entries on holism and nonseparability in physics and quantum entanglement and information).

Humphreys (2016) construes this as an instance of emergent fusion (section 4.2.4). Insofar as these features have physical effects, they indicate a near-ubiquitous failure of whole-part property supervenience at a very small scale. However, it should be observed that quantum entanglement does not manifest a fundamental novelty in feature or associated causal power, as it concerns only the value or magnitude of a feature/associated power had by its components. (Correlated “spin” values, e.g., are permutations on the fundamental feature of spin, rather than being akin to mass or charge as wholly distinctive features.) As such, it does not fit the criteria of many accounts of strongly emergence.

It is, however, relevant to the epistemic status of such accounts: if one thinks that the existence of strong emergence is implausible on grounds that a kind of strong local supervenience is a priori very plausible for composed systems generally, then the surprising phenomenon of quantum entanglement should lead you to be more circumspect in your assumptions regarding how complex systems are put together.

-

Moliere

6.5kThe philosophy I'm interested in recognises the empirical reality of past events, the pre-history of life before man and so on. But the reality that is imputed to them, is still imputed by an observing mind - yours, mine and whomever else considers the matter. The question is, is temporarility itself truly independent of any observing mind? And if the answer is yes, according to what scale or perspective is it so? Time - the measurement of duration - seems to me to depend on scale or perspective, and that is what it provided by the observing mind. None of which is to deny the reality of the fossil record. — Wayfarer

Moliere

6.5kThe philosophy I'm interested in recognises the empirical reality of past events, the pre-history of life before man and so on. But the reality that is imputed to them, is still imputed by an observing mind - yours, mine and whomever else considers the matter. The question is, is temporarility itself truly independent of any observing mind? And if the answer is yes, according to what scale or perspective is it so? Time - the measurement of duration - seems to me to depend on scale or perspective, and that is what it provided by the observing mind. None of which is to deny the reality of the fossil record. — Wayfarer

Time seems as independent as anything else in empirical reality, but if we're talking about transcendental idealism, for instance, then it seems the answer is both yes and no -- time is independent of my observing mind in the sense that I can have incorrect judgments about the form of our intuition, but it also just is a part of our mental structuring of the world (so it wouldn't even make sense to claim dependence as much as identity).

I don't know, though, and I remain uncertain how one might go about deciding such a thing. It seems like a question we can ask but that doesn't have much of an answer if we want to claim to know. -

Christoffer

2.5kBut the philosophical point about the inherent limitation of objectivity remains. — Wayfarer

Christoffer

2.5kBut the philosophical point about the inherent limitation of objectivity remains. — Wayfarer

It remains mostly just as a remark of an obvious observation on human perception, but it fails to lock down limitations as actual limitations of knowledge. We cannot see all wavelengths of light, but we know about them, we can simulate them, we use them both in measurements and in technology. Understanding reality doesn't require limitless perception, nor is it needed.

To pose that we must have limitless perception in order to understand reality downplays our actual ability of abstract thinking.

And it also produces another question; would unlimited perception of reality actually produce perfect understanding or would it just scramble the ability to understand everything by the lack of defined perspectives? That without a specific perceptive perspective and clear categorization while able to do abstract reasoning that relates to those perspective, it may form better understanding than the unlimited. A being that, for instance, would see all wavelengths of light, may not comprehend light any better than us due to the absolute visual noise it would produce. In that scenario there wouldn't be any actual ability to see matter easily and, therefor, that being would of course see more than us in terms of photons, but it would see less than us due to photons interacting with matter drowning in the sea of the wavelengths we don't see.

So to pose that our limited perception is limiting us isn't a strong conclusion because we could also argue that our perception strikes the perfect balance of perceptive observation that makes reality able to be navigated and understood more easily while we further have the ability through abstract thinking, mathematical calculations and building external tools to extend our comprehension.

As an analogy, in art, there are clear examples in which an artist had unlimited means to make whatever they wanted, without any problems with funding, equipment or inspiration and yet they were only able to produce something that people felt became worse than when they were stuck with limitations. We cannot conclude perceptive limitations to be equal to an inability to fully understand reality, not when incorporating our other mental abilities and capacity for creating technology to extend our abilities, as well as realizing how limitations in perceptions can make understanding cleaner. Absolute, limitless perception might just become an incomprehensible mess that renders a clear picture into white noise and "objective conclusions" lacking even more details. So when would a being be able to understand the universe fully? Because limitations in perception doesn't seem enough of a defining criteria based on this.

I recall a quote from a philosopher of science along the lines of facts being constructed like ships in bottles, carefully made to appear as if the bottle had been built around them. — Wayfarer

Carl Sagan? He emphasizes the idea that sometimes people construct their beliefs first and then selectively choose or interpret facts to support those beliefs. Which is why modern scientific methods are rigorously focused on bypassing such biases. The ship in bottle-analogy refers primarily towards those conducting pseudo-science, empathizing the need for rigorous critical thinking, evidence, and scientific principles. Which is what I'm standing by as well when I say that my philosophical speculations are extrapolated out of science, not out of a belief first that I'm then searching for evidence to support. I did not focus much on emergentism before many scientific fields started to form similar conclusion in their analysis of extreme complexity. While the concept of emergence has been around for long in philosophy, it's only recently, with progression in things like criticality, that it starts to lean into the most probable position. And as I've mentioned, if it turns out to be false due to new discoveries, then I will simply have to shift my perspective to something that's more probable. I will not, however, change my perspective into something that relies on belief alone and cause just because it feels good or present me a sense of emotional meaning.

If, by 'laws of reality' you mean 'natural law' or 'scientific law', are these themselves physical? I think that is questionable. The standard model of particle physics, for instance, comprises an intricate mathematical model, or set of mathematical hypotheses. But are mathematics part of the physical world that physics studies? This as you know is a contested question, so I'm not proposing it has a yes or no answer. Only that it is an open question, and furthermore, that it's not a scientific questio — Wayfarer

The laws of reality or physical laws are the mathematical principles that guide processes in physics. Mathematics are just our way of extrapolating an understanding of the unseen. The equations we have is a language for interpretation and extending such interpretation to prediction has proven to guide how we test physics, and in turn successfully proven physics to a point in which we can act upon and manipulate it, which is why we have most of the technology we have today.

So are they part of the physical world? Math on a board and in our head, no, they're just the lens for which we see these underlying rules of the physical world. But they correlate, and something like the fine structure constant; its mathematical calculation is extrapolated out of the phenomena we observe and through that we can measure its impact beyond our perception.

The standard model is what's proven, the hypotheses part is what we extend out from it, theories that tries to breach into a theory of everything. For instance quantum electrodynamics is one of the most accurate theories in all of physics. Even if we found out that it is something else or part of something else, the math of its function remains and exist as a physical phenomena. Science does not prove something "wrong" with new discoveries, they prove a new relation and perspective that put previous knowledge in new light and a new framework. It's a slowly forming knowledge, like a statue that's forming by water droplets, slowly coming into shape. It's not a finished statue that's demolished and rebuilt from scratch with new discoveries. And math is the reason why, because the answers in math cannot be changed, only understood better.

String and M-theory are one of those areas where the only reason why it keeps existing is because the math works. If proven wrong, the math will still stay and have to be incorporated into what is proving it wrong.

Furthermore physics itself has thrown the observer-independence of phenomena into question. That, of course, is behind the whole debate about the observer problem in physics, and the many contested interpretations of what quantum physics means. I know that is all a can of worms and am not proposing to debate it, other than to say that both the 'physicality' and 'mind-independence' of the so-called 'fundamental particles of physics' are called into question by it. — Wayfarer

The "observer" in quantum physics has to do with any interaction affecting the system. When you measure something you need to interact with the system somehow and that affects the system to define its collapsing outcome. This has been wrongfully interpreted as part of human observation, leading to pseudo-science concepts like our mind influencing the systems. But the act of influence is whatever we put into the system in order to get some answers out. A photon launched at what is measured, for the purpose of a detector to then visually see what's going on; will have that photon affecting the system being measured. It's not that our mind does anything, it's that we have to put something in to get information out and the only way for the system to keep a superposition is to not have any influence, which means it is in suspended and dislodged from reality until defined.

If Christoffer responds to this and tries to correct your misconceptions, do you consider it likely that you will be inclined to tell him that his response was too long?

If so, it would be considerate to say so now. — wonderer1

:lol: This is more accurate than any prediction in physics

Sorry, I thought you were referring to the post I responded to. We'll see. — Wayfarer

:lol:

You ask questions and write about complex physics; it's like asking how an airplane function expecting a short answer, but if my answer is "it flies", that wouldn't be much of an answer really.

If the problem with explaining apparently emergent phenomena is just that you need a "lot more computational capabilities," then what you have is merely 'weak emergence,' and reduction still works. — Count Timothy von Icarus

That's why in my very first post in this thread I said this:

I would posit myself as a physicalist emergentist. What type is still up in the air since that's a realm depending on yet unproven scientific theories. — Christoffer

The question is still if it is possible and I cannot conclude either. But weak emergence and reductionism are not the same. Reductionism heavily focuses on clear basic interactions of the parts and direct relations to the higher sum property, while weak emergence still focus on how the interactions create levels of changes that propagate up to an emergent phenomena. The difference is that reductionism draws clear lines from the actions of the parts towards the effect, while weak emergence is a "slowly mixing liquid" where all steps in its progression becomes further part of the final emergence. You could still, if possible, calculate the progression with enough computing power, but it will not show clear causal lines, but instead a trace of the progression of changing operations within the system over time from initiation to emergent outcome.

A striking feature of quantum mechanics is known as “quantum entanglement”. When two (or more) quantum particles or systems interact in certain ways and are then (even space-like) separated, their measurable features (e.g., position and momentum) will correlate in ways that cannot be accounted for in terms of “pure” quantum states of each particle or system separately.

Quantum entanglement is a misunderstood concept. It simply means that a particle set in a relationary superposition with another particle and those particles are separated and then one particles spin is measured will give you information on what the other particle has in its spin since they are in relation. It doesn't mean we can directly affect a particle over long distances as a form of "sent information", only that the superposition when measured gives us information about the other distant particle.

Your post seems to blend two ideas though. That our conceptual framework is fundementally lacking, and that we simply lack computational power adequate to "brute force," our way through these issues. I would just ask if these are the same position vis-á-vis emergence? — Count Timothy von Icarus

It's about acknowledging the missing parts. We don't know if we can calculate or not, because we don't have the computational power yet. When we do, this will be a testable part of physics. So we cannot conclude our knowledge-relation to emergence yet, even if we can see it happening. Much like how we can see both general relativity working as well as quantum mechanics, but not have a theory combining them at this time. I'll speculate that we might even find clues to such a bridging theory of everything within emergence theories, seen as they focus on the shifting relation between smaller chaos into larger deterministic systems.

The way collapsing wave-functions happen sure do resemble the emergence from high complexity, if that complexity comes from things like virtual particles. Or it may just be that the collapse is based on superpositions dancing between probabilities until they're settling in one or the other direction, similar to a drop of water between two other drops of water pulling on its tension and then randomly ends up in one or the other. Meaning, there may be a fundamental randomness of existence at the Planck scale, in which mathematical and universal constants define where the random existence and non-existence forms and in what way. And some of this randomness ends up in a condition where it locks into place by attaching and guiding the ones already locked in place, and which causally scales up to collapsing into such a locked position which defines moment to moment reality. A form of fundamental emergence that flows like a fluid with an increasing ability for causality through scale; from extreme randomness to slowly solidifying into more and more defined states at higher and higher scales. If that's the case, it might be that at the largest scales, scale levels of the entire universe, there's no emergence happening, forming a boundary where reality cannot progress further and that the only thing expanding our universe is the underlying emergence pushing reality larger, explaining both the increasing speed of the expansion and maybe even dark energy.

But that's just some pure speculation at the edge of my mind, so grains of salt required or course.

With the former view, I do think it's quite fair to ask if superveniance and thus "emergence" are even framed in the right terms, using the right categories. This is in line with process-based critiques of the entire problem, that it rests on bad assumptions baked into science that go back as far as Parmenides. The "lack of computational power," explanation seems like a different sort of explanation. — Count Timothy von Icarus

What are the right categories? These categories are just frameworks for further thought, accumulating the broad grouping of ideas in order to communicate better the position being discussed. I personally do not like the labeling and use of labels in philosophy because I think they limit thought down to people throwing balls with labels on them, defined, and for some, unmoving and unchanging concepts that when someone extends a label outside of its "comfort zone" people rebel and proclaim it not correct according to said label. Physicalist emergence is just a starting point for me.

It's probably why philosophical debates goes on for so long. Most people don't use the ideas of previous philosophy as a springboard, they simplify it down into labels and use them as hammers. I can find ideas in Wayfarer's idealism argument that I fundamentally agree with, but not with the conclusion, so does that make me a pseudo-idealist? No, it's only about following where the ideas lead based on rational thought and logic. Emergence as I'm talking about it, is referring to the underlying behavior of nature and our universe to assemble into further concepts that act with functions not possible to be defined by their parts, and further what that means and how it acts upon reality. So trying to purely define ideas based on how well they fit into categories is part of the limitations in Wayfarer's idealism argument that I agree with; that we cannot progress knowledge by only acting out of predetermined categorization. If emergence as I argue about it, produces new positions not able to be defined, then maybe a new category is needed to define it? -

Mark Nyquist

783

Mark Nyquist

783

You got me thinking about what time is.

For our brains we might have a special case because we perceive events and construct time lines. Past, present and future with the present being physical. That's my generalization of how we perceive time. It might not be the case physically. Matter doesn't flash in or out of existence based on clock time. Look at anything of matter and it has a stability and presence that doesn't come from a timeline or follow a clock. So look out as far as you can and as closely as you can and that might give you the best understanding of what physical matter is.

Of course for us we remember things in story form, events, calendar and clock time. If you think of a time line you have the past to the left, the physical present in the middle (an instant) and the future to the right. I think most people view past and future as physically non-existent but maybe that is my bias.

I think, for myself, I use different models of time based on the context and even can consider time as not a real thing....more a view that it is forever the physical present. -

Wayfarer

26.1kBut the philosophical point about the inherent limitation of objectivity remains.

Wayfarer

26.1kBut the philosophical point about the inherent limitation of objectivity remains.

— Wayfarer

It remains mostly just as a remark of an obvious observation on human perception, but it fails to lock down limitations as actual limitations of knowledge. We cannot see all wavelengths of light, but we know about them, we can simulate them, we use them both in measurements and in technology. Understanding reality doesn't require limitless perception, nor is it needed. — Christoffer

I'm not talking about the limits of knowledge. There is no end of things to discover. I'm talking about the limitations of objectivity as a mode of knowing.

Carl Sagan? He emphasizes the idea that sometimes people construct their beliefs first and then selectively choose or interpret facts to support those beliefs. — Christoffer

I looked it up - facts as being like 'ships in bottles' was from a philosopher called Jimena Canales, mentioned here some time back, link here. The point is, facts are always embedded in a context - theoretical, historical, social, and so on. The point about classical physics was that its calculations and predictions were not dependent on context in the way that higher-level and less straightforward sciences are. They are universally applicable, within a range. Physicalism generally wishes to extrapolate that method to knowledge in general.

The "observer" in quantum physics has to do with any interaction affecting the system. When you measure something you need to interact with the system somehow and that affects the system to define its collapsing outcome. This has been wrongfully interpreted as part of human observation, leading to pseudo-science concepts like our mind influencing the systems. But the act of influence is whatever we put into the system in order to get some answers out. — Christoffer

Not according to Brian Greene:

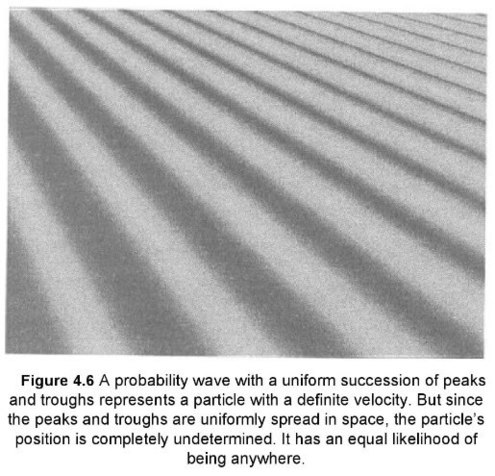

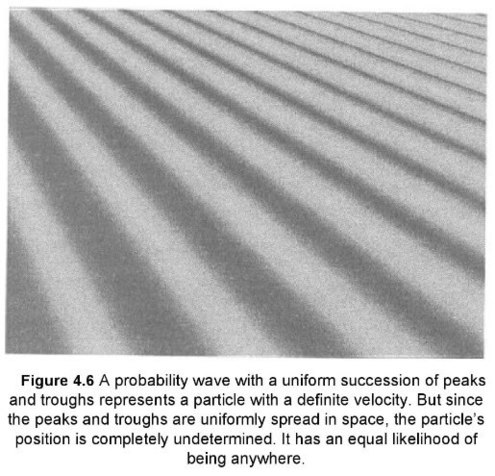

The explanation of uncertainty as arising through the unavoidable disturbance caused by the measurement process has provided physicists with a useful intuitive guide… . However, it can also be misleading. It may give the impression that uncertainty arises only when we lumbering experimenters meddle with things. This is not true. Uncertainty is built into the wave structure of quantum mechanics and exists whether or not we carry out some clumsy measurement. As an example, take a look at a particularly simple probability wave for a particle, the analog of a gently rolling ocean wave, shown in Figure 4.6.

Since the peaks are all uniformly moving to the right, you might guess that this wave describes a particle moving with the velocity of the wave peaks; experiments confirm that supposition. But where is the particle? Since the wave is uniformly spread throughout space, there is no way for us to say that the electron is here or there. When measured, it literally could be found anywhere. So while we know precisely how fast the particle is moving, there is huge uncertainty about its position. And as you see, this conclusion does not depend on our disturbing the particle. We never touched it. Instead, it relies on a basic feature of waves: they can be spreak out. — Brian Greene, The Fabric of the Cosmos

It is a fact that when the measurement is taken (or a registration is made) then the previously 'spread-out' nature of the 'particle' suddenly assumes a definite position. That is the (in)famous wave-function collapse the nature of which is still a matter of contention. It was what lead Wheeler to say that 'no phenomenon is a phenomenon until it is a registered phenomenon'. This is the sense in which quantum physics definitely mitigates against physicalism, and why you are compelled to dispute it. -

AmadeusD

4.2kI watched a Sideprojects this morning where Simon Whistler went over the misunderstandings around Schroedinger's Cat.

AmadeusD

4.2kI watched a Sideprojects this morning where Simon Whistler went over the misunderstandings around Schroedinger's Cat.

The indeterminacy is affected as much by the geiger counter as a human (or cat) eye/brain complex and collapses the wave-function in the same way. So, there's not really anything mysterious in the box anyway -

Wayfarer

26.1kA lot of people try to wave away the perpexities sorrounding quantum physics. I'm not a physicist, but I've discussed it with physicists, including posting detailed questions on Physics Forum and reading a pretty extensive list of books. And I don't believe anyone who says there is 'no mystery' around it. But I'm not going further along that line, as it's a famous derailer. Suffice to say, I'm one of the many who claim that quantum physics has forever torpedoed any simple form of physicalism. What remains is a general commitment to scientific method as the royal road to truth, a.k.a. 'scientism'.

Wayfarer

26.1kA lot of people try to wave away the perpexities sorrounding quantum physics. I'm not a physicist, but I've discussed it with physicists, including posting detailed questions on Physics Forum and reading a pretty extensive list of books. And I don't believe anyone who says there is 'no mystery' around it. But I'm not going further along that line, as it's a famous derailer. Suffice to say, I'm one of the many who claim that quantum physics has forever torpedoed any simple form of physicalism. What remains is a general commitment to scientific method as the royal road to truth, a.k.a. 'scientism'. -

jgill

4kThanks for the Brian Greene piece. My only reservation is that unless one is careful in reading it one might think the illustrated wave is the particle, whereas the illustration is the probability wave for the particle, which itself can assume a wave form. Is he saying the probability wave is the particle?

jgill

4kThanks for the Brian Greene piece. My only reservation is that unless one is careful in reading it one might think the illustrated wave is the particle, whereas the illustration is the probability wave for the particle, which itself can assume a wave form. Is he saying the probability wave is the particle?

But perhaps I am misinterpreting it. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIs he saying the probability wave is the particle?

Wayfarer

26.1kIs he saying the probability wave is the particle?

But perhaps I am misinterpreting it. — jgill

As you know, the 'wave-particle duality' is one of the fundamental oddities of quantum mechanics. Bohr said, as I understand it, that you can't see whether it 'really is' a wave or a particle - that whether it appears as wave or particle depends on the way you set up the experiment ('nature exposed to our method of questioning' was another pithy aphorism.)

But the reason I posted it, was in response to the claim that there's nothing mysterious about the whole wave-function collapse business, we just change the object because of interfering with it. That really overlooks the greatest philosophical conundrum of modern physics. Not claiming that I can adjuticate it or have the definitive interpretation, so much as pointing out that (1) nobody can and (2) there isn't one. -

jgill

4kA particle can assume the characteristics of a wave in an experiment and can be shown to exhibit the characteristics of a more conventional particle by changes in the experiment. But the wave form of the particle is not the probability wave of the particle is it?

jgill

4kA particle can assume the characteristics of a wave in an experiment and can be shown to exhibit the characteristics of a more conventional particle by changes in the experiment. But the wave form of the particle is not the probability wave of the particle is it? -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

I'm not sure I have starting-points as such. I'm just interested to understand what's going on here. I guess you're telling me that emergence only exists within a quite tightly defined context.If substance metaphysics, causal closure, and superveniance are your starting points, — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think that's a very good point.After all, if mind is strongly emergent, and thus a fundamental, irreducible force with sui generis causal powers, how is that not what people generally mean by dualism? — Count Timothy von Icarus

I only meant that providing ourselves with conceptual frameworks that are manageable is quite an achievement and well worth having.I see weak emergentism as most reasonable, and in the context of weak emergence the emergence is only epistemic. So on this way of looking at things there is nothing for emergence to do, except provide cognitively limited being like ourselves with conceptual frameworks that are manageable. — wonderer1

I think the devil is that is in those little words "just" and "is". Do we need any more that multiple descriptions in different contexts?Of course it is your brain is processing the data from your eyes. But it's still a cat, and it's still just a line. — Banno

I have very little idea what emergence is, but I'm thinking of it as a kind of analysis in reverse.Emergence, if it is to help us here, has to be akin to "seeing as", as Wittgenstein set out. So once again I find myself thinking of the duck-rabbit. Here it is enjoying the sun. — Banno -

Wayfarer

26.1kBut the wave form of the particle is not the probability wave of the particle is it? — jgill

Wayfarer

26.1kBut the wave form of the particle is not the probability wave of the particle is it? — jgill

But what is the probability wave, other than a distribution of probabilities? The answer to the question ‘where is the particle’ just IS the equation, right up until the time it is registered or measured. So the answer to the question ‘does the particle exist’ is not yes or no. The answer is given by the equation. So you can’t unequivocally say ‘it exists’ - you can only calculate the possibility that it might. (This torpedoes Democritus ‘atoms and the void’ by the way.)

So - does that mean ‘yes it is?’ - let’s ask @noAxioms.

Second point - this is one of the questions I asked on Physics Forum - it is well-known that if only one particle at a time is fired in the double-slit experiment, a wave interference pattern still occurs. But the intriguing thing is that even if you increase the rate, you still get the same pattern (up to a point). I posited that this indicated that time (rate being a function of time) was not a factor, meaning something like a ‘timeless wave’ - which was declared ‘gobbledygook’ by my interlocutor (ref).

So I don’t think of the wave function as a physical wave, but a pattern of degrees of likelihood. So the wave is in the fabric of reality itself, not the fabric of space-time.

But I know I’m on thin ice. -

Christoffer

2.5kI'm not talking about the limits of knowledge. There is no end of things to discover. I'm talking about the limitations of objectivity as a mode of knowing. — Wayfarer

Christoffer

2.5kI'm not talking about the limits of knowledge. There is no end of things to discover. I'm talking about the limitations of objectivity as a mode of knowing. — Wayfarer

And that returns to the question of at which level of perception an objective understanding, a knowing, is preferable. The one which is in the middle, seeing clearly past the absolute noise but with the ability to abstractly understand beyond? Or the one who sees all, but becomes blinded by its noise?

I agree that we have limitations in our perception and that a new perception could drastically change our emotional experience of how we experience reality and the universe. Much like when people saw the first images from Hubble, it changed the emotional experience of knowing the universe. However, that's only emotional experience. Objectivity in knowing, requires a humble and unbiased relation to the knowledge we have, respecting the data that forms a deeper understanding past our perceptive limits. And we have another tool for knowing; in form of the collective. All who are versed in how biases affect us knows that the more there are who observe without bias, the more objective we can be about reality.

Let's say we have a white room, evenly lit. In this white room there's a white podium with a red apple. Outside the room there's a person who do not know what's in the room. You let another person into the white room to observe and then out to describe and draw what they saw in the room to the first person. That wouldn't lead very far in his objective understanding of the apple and how it looks. But it will increase with more people that enters the room, giving their descriptions. At a certain point, the first person will have enough understanding of the red apple to predict exactly everything there is and be able to imagine the red apple in its entirety. Now, this looks an awful lot like another version of Mary and the black and white room. And that's intentional because when Mary steps out into a world of color she experience it emotionally. But the question is then, are we describing simply emotional experience? A purely human perspective that should not really be a foundation for objective understanding. To understand the universe, we do not need an exceptional emotional experience of it and fundamentally we are already doing something like that through art.

There's a beautiful expression of this in the Oppenheimer movie; in the montage after he gets asked the question by Bohr: "do you hear the music?" -Oppenheimer battles through the theory and there's a shot of him deep in thought in front of the Picasso painting Femme assise aux bras croisés. Art has been instrumental for experiencing beyond mere perception, and it is worth asking the question if the interpretation and honest imagination of information is more clear and objective in understanding than the being who can observe everything as everything is. Because, as I said, seeing all would blind you maybe even more than not seeing all due to your limitations.

What is an objective understanding then? Especially when reality seem to fluctuate in a away that makes the objective in objective understanding; a variable entity at that level of absolute perception. Understanding may very well be more clear with some limitations and so the conclusion that we cannot objectively understand becomes a very undefined conclusion.

Not according to Brian Greene: — Wayfarer

That was just a segment on the uncertainty principle. What causes the collapse is still about how any detection introduces an interference that collapses the wavefunction. And our mind does not affect the collapse because any measurement we use in order to witness it introduces an observable event long before our mind. Much like our eyes do not see by spraying out photons, the photons have already interacted with any surface and we only observe with our eyes after the photons already acted upon the world. Any interaction is a type of observer, because "observer" in physics has to do with interaction, relation. Anyone who uses the Von Neumann interpretation misunderstands a large part of physics and believes that they can isolate a physical phenomena in their lab without their equipment affecting the measurement. There's a reason why the Von Neumann interpretation is considered the worst of the interpretations, because even among physicists there are people who don't understand quantum mechanics. As Richard Feynman said; "if you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don't understand quantum mechanics".

This is the sense in which quantum physics definitely mitigates against physicalism, and why you are compelled to dispute it. — Wayfarer

Physicalism also points out that physical processes are causes. The problem is, as I mentioned in my last post in my answer to Count Timothy von Icarus, that philosophers gets addicted to labels. It becomes hammers to battle with rather than positions to extrapolate out from. If I present an argument that uses physicalist emergentism as a springboard into my philosophical ideas, then the label is only the starting point. If all I said gets reduced back to rigid descriptions of these labels, then you are acting out of the same criticism you've given for how scientists can only observe through pre-conceived categories.

It's why I usually never use these labels when talking about different topics, because it collapses people's ideas back into a box that makes it harder for them to read what I actually write. It's also fascinating that when we read philosophy, all these labels and terms get invented by the notable philosophers in history, but when people discuss philosophy and operate on expanding on ideas, they mostly become puppets of these labels, using them as tribalist positions. But true philosophy is about understanding the ideas and work out from it. Since it seems that physicalist emergentism as a label is boxing in my argument in a framework that is limiting, I think I need to coin my own terms for it. But since the science of criticality is still in very early stages I want to wait until there are more of a foundation for emergence theories. -

Moliere

6.5kTime is a great topic.

Moliere

6.5kTime is a great topic.

I began to notice differences in conceptions in time when I started getting into historiography. As you note there are many models of time.

I believe past events must at least exist. What is non-physical about the Earth forming in the distant past? Or weather events? It seems to me that the mountains of today were physical yesterday, or at least as physical as they are today. Would time rob them of that physicality because we've moved past them, or do they remain physical even though it was yesterday? -

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

The probability of measuring some part of a system can be computed from the wave function. I've not heard the result of that computation being referred to as a 'wave', but I'm sure it is somewhere.But what is the probability wave, other than a distribution of probabilities? The answer to the question ‘where is the particle’ just IS the equation, right up until the time it is registered or measured. So the answer to the question ‘does the particle exist’ is not yes or no. The answer is given by the equation. So you can’t unequivocally say ‘it exists’ - you can only calculate the possibility that it might. (This torpedoes Democritus ‘atoms and the void’ by the way.)

So - does that mean ‘yes it is?’ - let’s ask noAxioms. — Wayfarer

Does the particle exist? That's a counterfactual, so there is only a yes/no answer given an interpretation that posits counterfactuals. Quantum theory would simply give a probability of measuring it here or there, or not at all. You can confidently say about some proton that it 'exists' mostly because outside of the sun, protons are pretty stable * and don't just cease existing, so it exists but you don't know exactly where it will be next measured.

I was asked if 'yes it is' is correct, in reference to:

No it is not. The wave function of the particle describes its quantum state. The probability of where it might be computed from that wave function, but the wave function itself is not a 'probability wave'.But the wave form of the particle is not the probability wave of the particle is it? — jgill

Right. This shows that the interference pattern (from a continuous beam say) is not due to the photons interacting with each other.it is well-known that if only one particle at a time is fired in the double-slit experiment, a wave interference pattern still occurs.

Up to a point? What happens if you go beyond that point, other than the slits melting or something? Got a citation?But the intriguing thing is that even if you increase the rate, you still get the same pattern (up to a point).

* 15O (with a half-life of a couple minutes) decaying into 15N is an example of an everyday non-violent end of a proton that might be observed in a lab here on Earth. A PET scanner apparently uses exactly this reaction to study oxygen / blood flow. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

This quote raised a strange & confusing possibility in my mind, that may or may not be provable. Greene's illustration of quantum Uncertainty*1 notes that the "particle" being sought is not in any particular place, but "spread out" throughout the universe. In other words, non-local. So, it seems that the fundamental problem is not a mental state (uncertainty) in the mind of the observer, but a Holistic state (eternity) in the really-real world. Ironically, the reductive scientist is looking for a particle where there is nothing particular. This sounds like the drunk looking for his lost keys under a street light, because that's where the light is.*3Not according to Brian Greene:

The explanation of uncertainty as arising through the unavoidable disturbance caused by the measurement process has provided physicists with a useful intuitive guide… . However, it can also be misleading. It may give the impression that uncertainty arises only when we lumbering experimenters meddle with things. This is not true. Uncertainty is built into the wave structure of quantum mechanics and exists whether or not we carry out some clumsy measurement. As an example, take a look at a particularly simple probability wave for a particle, the analog of a gently rolling ocean wave, shown in Figure 4.6. — Wayfarer

From direct sensory experience with the human-scale macro world, we have learned to expect things to be local & particular & changeable. But, when scientists experiment with the quantum foundations of the world, their artificial sensors return the appearance of a non-local & holistic & a-causal BlockWorld*4. In such a world all reasoning would be circular (non-linear). So, which is true : our common-sense ever-changing linear-logic reality, or an eternal state of Potential from which we sample statistical contingencies? What does this possibility say about Physicalism? :smile:

*1. Quantum Uncertainty :

Philosophers of science have long associated the claim that observations or experimental results in science are in some way theory-laden with a logical/epistemological problem regarding the possibility of scientific knowledge: reasoning from theory-laden observations may involve circularity. . . .

Measurement results depend upon assumptions, and some of those assumptions are theoretical in character. . . . . Our analysis shows how the evaluation and deployment of uncertainty evaluation constitutes an in practice solution to a particular form of Duhemian underdetermination[*2] that improves upon Duhem's vague notion of “good sense,” avoids holism, and reconciles theory dependence of measurement with piecemeal hypothesis testing.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0039368120301886

Note --- Theories tend to become beliefs to be verified, or if not provable, to be accepted as ever-pending facts. Accepting quantum Uncertainty as a brute fact of life, allows us to "avoid" the logical conclusion of Holistic (non-reductive) foundation of Reality.

*2. Underdetermination :

In the philosophy of science, underdetermination or the underdetermination of theory by data (sometimes abbreviated UTD) is the idea that evidence available to us at a given time may be insufficient to determine what beliefs we should hold in response to it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Underdetermination

*3. Why quantum mechanics favors adynamical and acausal interpretations such as relational blockworld

We articulate the problems posed by the quantum liar experiment (QLE) for backwards causation interpretations of quantum mechanics, time-symmetric accounts and other dynamically oriented local hidden variable theories. We show that such accounts cannot save locality in the case of QLE . . . . In contrast, we show that QLE poses no problems for our acausal Relational Blockworld interpretation of quantum mechanics, which invokes instead adynamical global constraints to explain Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR) correlations and QLE. We make the case that the acausal and adynamical perspective is more fundamental and that dynamical entities obeying dynamical laws are emergent features grounded therein.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1355219808000592

Note --- This source is over my head. But it seems to be arguing that Einstein's hypothetical timeless & changeless & placeless Block Universe may be more real (in some strange sense) than the dynamic particular world that our senses interpret as Reality.

*4. EINSTEIN'S ETERNAL BLOCK WORLD

-

RogueAI

3.5kI don't see any reason to think such a system couldn't in principle be conscious, but it would be an extremely low temporal resolution sort of consciousness, and would require an enormous input of energy to power the pumps. This is related to what I pointed out Kastrup showing ignorance about, with his claim that the relationship between fluid flowrate and pressure, is the same as the relationship between voltage and current expressed by Ohms law.

RogueAI

3.5kI don't see any reason to think such a system couldn't in principle be conscious, but it would be an extremely low temporal resolution sort of consciousness, and would require an enormous input of energy to power the pumps. This is related to what I pointed out Kastrup showing ignorance about, with his claim that the relationship between fluid flowrate and pressure, is the same as the relationship between voltage and current expressed by Ohms law.

So your conciousness detector would need to be able to detect a consciousness, for which one of our years was but a moment. — wonderer1

This is where we disagree. I don't see a compelling reason to think the needle of the consciousness meter would move at all if we pointed it at a conglomeration of pipes, pumps, and valves. Science, so far, has not come up with a compelling reason why I should think there's something it's like to be New York City's sewer system. There's been plenty of research establishing brain-consciousness correlations (if one assumes materialism is true), but nothing so far on the causal front. I think Kastrup is clearly correct here.

It's also kind of head scratching that the same people who shout "Woo!" at the drop of a hat would entertain the notion that plumbing might be conscious. -

RogueAI

3.5kNo one has suggested the possibility of NY sewers being conscious, so that is just a strawman. — wonderer1

RogueAI

3.5kNo one has suggested the possibility of NY sewers being conscious, so that is just a strawman. — wonderer1

So it's impossible for certain conglomerations of plumbing to be conscious? Which systems of valves, pipes, pumps, etc. are possibly conscious and which aren't and how do you know? -

wonderer1

2.4kSo it's impossible for certain conglomerations of plumbing to be conscious? Which systems of valves, pipes, pumps, etc. are possibly conscious and which aren't and how do you know? — RogueAI

wonderer1

2.4kSo it's impossible for certain conglomerations of plumbing to be conscious? Which systems of valves, pipes, pumps, etc. are possibly conscious and which aren't and how do you know? — RogueAI

Why would I want to waste any more time, trying to explain the physical working of things, to someone who denies there is any physical working of things? -

RogueAI

3.5kWhy would I want to waste any more time, trying to explain the physical working of things, to someone who denies there is any physical working of things? — wonderer1

RogueAI

3.5kWhy would I want to waste any more time, trying to explain the physical working of things, to someone who denies there is any physical working of things? — wonderer1

I am not the one claiming that some assemblages of valves, pipes, etc. are possibly conscious and some are impossibly conscious. I think it's all impossible. When you claim that this heap of matter over here is possibly conscious, but it is impossible for that heap of matter over there to be conscious, that begs certain questions. You don't want to answer them, OK. But that weakens your case. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

We observe the entities in order to derive their properties, relations, and activities. I suspect I lack the necessary abilities to abstract a property from that which it is a property of, but I do not see how they can be distinct from one another. One cannot measure the mass of a thing without measuring the thing. -

jgill

4kThe probability of measuring some part of a system can be computed from the wave function. I've not heard the result of that computation being referred to as a 'wave', but I'm sure it is somewhere — noAxioms

jgill

4kThe probability of measuring some part of a system can be computed from the wave function. I've not heard the result of that computation being referred to as a 'wave', but I'm sure it is somewhere — noAxioms

The Schrödinger equation's solution is called a wave function. If one simplifies the equation considerably it has the form dQ/dt=kQ, which has solutions involving e^it=cost+isint, giving it repetitive or wave-like characteristics.

I apologize if I have misinterpreted your comment. -

Wayfarer

26.1kA purely human perspective that should not really be a foundation for objective understanding. To understand the universe, we do not need an exceptional emotional experience of it and fundamentally we are already doing something like that through art. — Christoffer

Wayfarer

26.1kA purely human perspective that should not really be a foundation for objective understanding. To understand the universe, we do not need an exceptional emotional experience of it and fundamentally we are already doing something like that through art. — Christoffer

Very many deep questions here. Again a large part of scientific method is in the reduction of observables to their measurable attributes, and the integration of the observable results into an over-arching hypothesis. My claim is that whilst this has been an incredibly effective method, there is something that it leaves out as a matter of definition. It provides what philosopher Thomas Nagel calls 'the view from nowhere', which attempts to understand the world independently of any personal or subjective perspectives and experiences, aspiring to a form of understanding that transcends any particular individual's perspective. It is scientifically effective, but philosophically barren, because in reality we are subjects of experience, we're not really standing outside or separate from our lives or existence as a whole. And that is very much the thrust of phenomenology and existentialism.

What happens if you go beyond that point, other than the slits melting or something? Got a citation? — noAxioms

Thanks for your response! As I mentioned before, I ran the idea past Physics Forum, where I was told that:

Q: So energy is a significant variable - if you vary the energy, you vary the resulting pattern - but rate is not. Would that be a valid conclusion, all else being equal?

A: Yes, but only up to the point where the rate is so high that the interaction between different electrons can no longer be neglected.

You can confidently say about some proton that it 'exists' mostly because outside of the sun, protons are pretty stable and don't just cease existing, so it exists but you don't know exactly where it will be next measured. — noAxioms

It's the nature of that existence which is the philosophical conundrum. It's not as if it's precise position and momentum is unknown, but that it's indeterminable. It will be found whenever it is observed, but the sense in which it exists when not being observed is what is at issue.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum