-

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

All of that is external to chess itself, the play of which is perfectly settled, and has been for a long time.

:up: I totally agree on that front. Although the phrasing does get at the suitability of chess as an analogy for mathematics and language, brought up earlier ITT. What is external to systems is often the very point in question, right? Are the players and their reasons for playing or for creating/changing the rules external to what chess is?

If we say that the bishop is only intelligible in terms of the other pieces and the rules of chess, or that words are only intelligible in terms of other words and the rules of a language, then it seems like the same thing should apply at a higher levels. That is, chess should only be intelligible in terms of its role in human culture, and language should only be intelligible in terms of its role in the world at large.

Generally though, the analogy is not always used like this. Chess pieces are said to only be intelligible in terms of the other pieces, (the formalist mantra: "a thing is what it does") but chess itself sits off alone in analytical space as a self-contained entity. Within the actual playing of these sorts of games, strategies come and go. People will talk about how "the game has changed," due to the use of data analytics, computers, etc. But is this change solely external? And if it is, how does this flow with the intuition that pieces, words, etc. are ultimately only intelligible in terms of their context?

I think the lens for looking at this probably depends on your questions. If your goal is an analysis of rules and games, it makes sense to think of them as discrete entities. If the question is something more like "how do words get their meanings and what is the relationship here to universals?" or "why do we do math and why is it useful?" I don't think the rules can be the limit of inquiry for exactly the same reason that you cannot explain the bishop without reference to all the rules. -

Leontiskos

5.6kGenerally though, the analogy is not always used like this. Chess pieces are said to only be intelligible in terms of the other pieces, (the formalist mantra: "a thing is what it does") but chess itself sits off alone in analytical space as a self-contained entity. — Count Timothy von IcarusI think the lens for looking at this probably depends on your questions. If your goal is an analysis of rules and games, it makes sense to think of them as discrete entities. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Leontiskos

5.6kGenerally though, the analogy is not always used like this. Chess pieces are said to only be intelligible in terms of the other pieces, (the formalist mantra: "a thing is what it does") but chess itself sits off alone in analytical space as a self-contained entity. — Count Timothy von IcarusI think the lens for looking at this probably depends on your questions. If your goal is an analysis of rules and games, it makes sense to think of them as discrete entities. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Great points. :up: -

Banno

30.6kNo, it doesn't.

Banno

30.6kNo, it doesn't.

An adequate explanation of "what quantifier variance is" would show the difference between at least two forms of quantifier. The quote says that there are two differing forms of quantifier, but does not say how they differ.

Folk hereabouts can verify this for themselves.

Whether there is a better explanation elsewhere in the text remains undecided.

Elsewhere:

DKL includes tables in his domain. PVI does not. Both make use of the very same rule for quantifier introduction.DKL: “There exist tables”

PVI: “There do not exist tables”

The deflationist: “something is wrong with the debate” — p.3

No case has been presented for a variance in the quantifier introduction rules, as opposed to a variance in the domain. -

Leontiskos

5.6kAn adequate explanation of "what quantifier variance is" would show the difference between at least two forms of quantifier. The quote says that there are two differing forms of quantifier, but does not say how they differ. — Banno

Leontiskos

5.6kAn adequate explanation of "what quantifier variance is" would show the difference between at least two forms of quantifier. The quote says that there are two differing forms of quantifier, but does not say how they differ. — Banno

No, this is completely wrong. Quantifier variance is a kind of insuperable second-order equivocation. Sider does not need to explicate two concrete usages of quantifiers to set out quantifier variance, any more than someone would need to explicate two equivocal terms in order to set out the meaning of equivocation. You are saying, "Sider didn't give an example of quantifier variance, therefore he didn't define quantifier variance." You're like the anti-Socrates, who receives a definition and then says that because it wasn't an example, therefore it wasn't a definition. -

Banno

30.6kThere is no definition in the quote you cite.

Banno

30.6kThere is no definition in the quote you cite.

Elsewhere:

DKL: “There exist tables”

PVI: “There do not exist tables”

The deflationist: “something is wrong with the debate”

— p.3

DKL includes tables in his domain. PVI does not. Both make use of the very same rule for quantifier introduction.

No case has been presented for a variance in the quantifier introduction rules, as opposed to a variance in the domain. — Banno -

Banno

30.6kBoth make use of the very same rule for quantifier introduction.

Banno

30.6kBoth make use of the very same rule for quantifier introduction.

D says that this is a table; P says that this is not a table. D can introduce a quantifier so: This is a table, therefore there are tables; tables exist. P introduces a quantifier thus: For any item you choose, it is not a table, therefore there are no tables, tables do not exist.

They can agree that the argument the other presents is valid, but disagree as to the premise, and so as to the conclusion.

Notice that they are both using natural deduction of the first order; they are using the very same logic.

Hence calling their difference a quantifier variance is misleading. They are taking the same logic and applying it to a different range of things.

This thread seems to have run its course. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kintelligible — Count Timothy von Icarus

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kintelligible — Count Timothy von Icarus

I'm not one of the people making these analogies, but I don't see any harm in distinguishing "how to play chess" from "why to play chess" or even from "why to play this game of chess this way." I can belabor the point if you'd like.

In fact, here's a little belaboring: consider Grice's distinction between what a sentence (literally) means and what someone means by uttering that sentence on a particular occasion. Now consider a question like "Why did you move the bishop to b5?" Would you answer "Because bishops move diagonally"? No you would not; you'd explain something about the position and why you thought Bb5 was a good move. (Ryle talks about this, the difference between your moves being in accord with the rules and your moves being determined by the rules.) ---- But also, a beginner might ask, "Why didn't you take his knight with your rook?" And you might point out that a pawn is in the way, and rooks can't jump.

Now consider the different sorts of questions you might ask about what someone said, or the different sorts of explanations you might have to give in different circumstances. Some of them, particularly with children, are very much on the "how to play" level, some on the "how to play well" level, and others are past that, and amount to actually playing -- but again, only in accord with the sort of rules you yourself were taught as a child. (Or not. Rules change. And sometimes you help change them.)

Your move.

what do you believe our heroes are promoting? — fdrake

Conceptual relativism on stilts. Which honestly I'm not absolutely against (unlike both @Banno and @Leontiskos) but I'm unsympathetic with the whole approach and nothing I've read was at all persuasive. -

Leontiskos

5.6k

Leontiskos

5.6k -

Wayfarer

26.1kI'm not one of the people making these analogies, but I don't see any harm in distinguishing "how to play chess" from "why to play chess" or even from "why to play this game of chess this way." I can belabor the point if you'd like. — Srap Tasmaner

Wayfarer

26.1kI'm not one of the people making these analogies, but I don't see any harm in distinguishing "how to play chess" from "why to play chess" or even from "why to play this game of chess this way." I can belabor the point if you'd like. — Srap Tasmaner

I recently watched a lecture on evolutionary neuroscience, which included a striking slide at 7:13 defining teleology as 'the explanation of phenomena in terms of the purpose they serve rather than the cause by which they arise.' I found this definition marvelously succinct.

In the context of your analogy, distinguishing between "how to play chess" and "why play it?" is indeed relevant, albeit obliquely, to the broader issue of quantifier variability. The question of "how to play" presupposes the existence of the game. In a culture unfamiliar with chess, the question of "why play it?" must be addressed first, if only to find someone else to play with. Chess is an artificially constrained experience with a definite aim—winning. However, real philosophical questions are not so constrained.

In chess, the existential quantifier is tied to the game's rules and objectives, which provides an implicit purpose. In real life, existence encompasses a broader and more varied range of possibilities and outcomes, without the clear constraints of a game, and with the existence of a purpose being harder to discern.

Thus, using chess as an analogy for existential questions might constrain our understanding in ways that don't necessarily apply to real life. This is the sense in which chess is a poor analogy for the question of different kinds of existence, as I understand 'quantifier variability'.

Am I getting it? -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kAnyhow, on the original topic, the idea that QV is a sort extension of the principle of charity seems wrong. Why? Because many individual thinkers argue for different types of "existence" within their metaphysics/ontology. In general, QV is framed using examples based on two different people debating what "exists" using supposedly "different languages."

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kAnyhow, on the original topic, the idea that QV is a sort extension of the principle of charity seems wrong. Why? Because many individual thinkers argue for different types of "existence" within their metaphysics/ontology. In general, QV is framed using examples based on two different people debating what "exists" using supposedly "different languages."

However, the idea that there are different "types" of existence (e.g. exist vs subsist, actualism, etc.) is often presented as part of a single comprehensive theory, one ostensibly using a single language and focusing on a single domain (normally "everything") For example, when Eriugena discusses his five modes of being, he clearly is intending one domain and not using "different languages," despite lines to the effect of "to say man exists is to say logoi do not exist (in the way that man 'exists')."We could consider here Meinong, Parsons, etc.

But it hardly seems in line with charity to presuppose that the positing of these distinctions in "ways of existing" (or levels/degrees of "reality") is always just a confusion of language. This is basically saying that these philosophers are:

A. Wrong and certainly not making real distinctions about how things are in the absolute sense they seem to be claiming.

B. Confused and obviously either varying their language or domain. This is essentially assuming that they must be making a mistake regardless of what their argument/theory looks like.

B in particular is why I think the linguistic turn often leads to a failure of the principle of charity. To simply assume that a whole swath of discussions in philosophy must only arise from philosophers' "confusion," rather than real problems is not charitable. At its worst it's question begging. For example, to say that Przywara must be switching languages or domains with the analogia seems to be saying he is wrong in an important way, or even moreso, just refusing to take his thought the way it is intended.

Second, multiple uses of "exists" or distinctions of "more/less real," do not seem to be to entail any sort of relativism or anti-realism. It is rather Hirsch's move to "resolve" disputes by reducing them to language that threatens this.

This definition, at least taken in isolation, seems to avoid the issues above to some degree. "...either because there is no such notion of carving at the joints that applies to candidate meanings, or because there is such a notion and C is maximal with respect to it." It is more the bolded part that leads towards relativism, not different uses of "exists/subsists/etc."

Edit: To clarify - in terms of other explanations that cannot be explained by "the human sensory system, psychology, neuronal structures/signaling, etc."

Well for one, an explanation of the words "dog" or "swimming," seems like it should require reference to dogs and water respectively, rather than just neurons. Explanations that draw a line around the brain seem to forget that brains do not work in isolation and do not produce consciousness in isolation. A constant exchange of information and causation across the boundaries of the human body is required to maintain consciousness. Place a human body in most of the environments that exist in the universe, on the surface of a star, in the void of space, in the deep sea, in a room filled with nitrous oxide, etc. and consciousness is not going to be produced. Context matters then for explaining how minds emerge (and minds must emerge for language). Any process of perception requires relations between the objects of perception, the observer, and the enviornment, and you can't seem to have language without first having perception.

Now consider the different sorts of questions you might ask about what someone said, or the different sorts of explanations you might have to give in different circumstances. Some of them, particularly with children, are very much on the "how to play" level, some on the "how to play well" level, and others are past that, and amount to actually playing -- but again, only in accord with the sort of rules you yourself were taught as a child. (Or not. Rules change. And sometimes you help change them.)

:up: Yup, this is sort of what I was thinking about with my last paragraph there. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

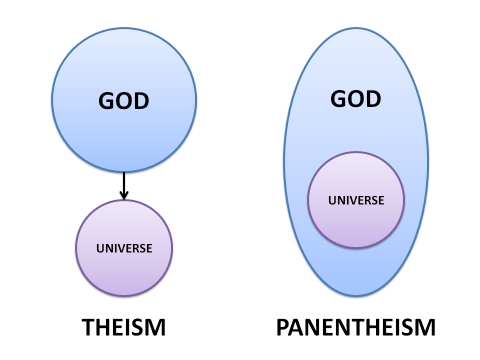

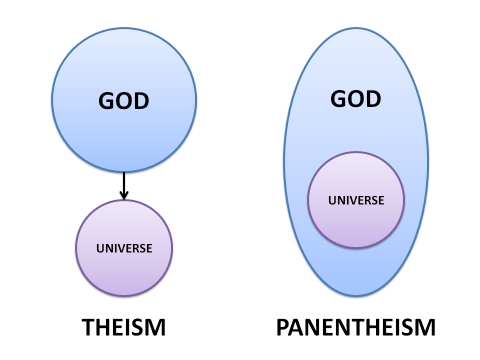

4.3kBTW, here might be a helpful example. Consider the panentheistic view that underscores Eriugena, Ulrich, etc.

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kBTW, here might be a helpful example. Consider the panentheistic view that underscores Eriugena, Ulrich, etc.

This image is helpful, but one should bear in mind that the outer circle in the classical tradition really should be infinite, without border, we just can't draw it this way.

The idea of different sorts of being, of analogy being the only way to tie them together is sort of like this: to be for finite being is to be contained within the inner circle. Infinite being is in the inner circle, but it isn't contained in it, it transcends it. Everything is part of the outer circle in some sense. The outer circle is generally the domain under consideration in metaphysics.

This is, in some ways, an inadequate image. It misses the distinction that subsistent relations only exist in God (Exodus 3:14).

So, are we simply switching to domain when we discuss different types of being? I don't think so. If the domain under discussion is the inner circle then infinite being is included but also transcends the domain. If the domain is the outer circle, then entities in the inner circle stand in a different relation to the whole, hence the "different sort of existence" (and bear in mind here that the ontology generally employed here is inherently relational.

The "is" of predication, identity, and existence are not separated out in the same way in this tradition. In part, this is because they were seen as deeply related. Given the view that things just are their properties (which are relational), a not unpopular view in contemporary metaphysics, the the sum total of what can be predicated of a thing is its identity, or at least something very close to it. Consider Leibniz Law: ∀F(Fx ↔ Fy) → x=y

Likewise, if existence (or actuality) is simply another predicate, then the "is of existence" is deeply tied to the "is of predication" which in turn is deeply related to the "is of identity." Finite existence then is of a different type in that finite things can be defined in terms of all other things, and indeed their properties and identity are bound up in this relationality. They are also mereologically distinct due to the principle of divine simplicity (a major motivator here).

This doesn't quite capture the idea of God as "nothing through excellence," (nihil per excellentiam) versus the "nothing of privation," (nihil per privationem), which is also key to the distinction. I do think this is a distinction in existence that flows from the ontology itself though

and cannot be reduced to differences in language.

In such a view, there is no Porphyryean tree that has infinite and finite being alongside each other. The image might mislead on this front. God is being itself whereas finite being has being through participation in infinite being. For God alone, existence and essence are the same. -

Leontiskos

5.6kTo simply assume that a whole swath of discussions in philosophy must only arise from philosophers' "confusion," rather than real problems is not charitable. At its worst it's question begging. For example, to say that Przywara must be switching languages or domains with the analogia seems to be saying he is wrong in an important way, or even moreso, just refusing to take his thought the way it is intended. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Leontiskos

5.6kTo simply assume that a whole swath of discussions in philosophy must only arise from philosophers' "confusion," rather than real problems is not charitable. At its worst it's question begging. For example, to say that Przywara must be switching languages or domains with the analogia seems to be saying he is wrong in an important way, or even moreso, just refusing to take his thought the way it is intended. — Count Timothy von Icarus

That's right, just as it is question-begging to assume that the different uses of "to be" are compartmentally distinct.

This is what Sider refers to as a "hostile translation" on page 14. It is interpreting or translating someone's utterance in a way that they themselves reject.

For example, when Eriugena discusses his five modes of being, he clearly is intending one domain — Count Timothy von Icarus

Sure, but this is not quantifier variance, or even quantifier equivocation. One could represent the five modes with predicates, or else with alternative quantifiers.

The debates about univocity of being can apply between parties or within the thought of a single party, but quantifier variance occurs between two parties using two different notions of quantification. If the two parties have five different sub-quantifiers, and they agree on all of them, then quantifier variance is not occurring. ...All of this is also reminiscent of the duplex veritas debates of the Middle Ages.

This definition, at least taken in isolation, seems to avoid the issues above to some degree. "...either because there is no such notion of carving at the joints that applies to candidate meanings, or because there is such a notion and C is maximal with respect to it." It is more the bolded part that leads towards relativism, not different uses of "exists/subsists/etc." — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think that distinction that Sider makes is important, and I see what you are saying. What I would say is that the bolded part leads to a more thoroughgoing conceptual relativism, but the latter option is still a form of conceptual relativism. It's just that in the latter case both candidate meanings do a good job, and an equally good job, of carving at the joints. This latter form, when applied to logic, represents Banno's logical pluralism.

---

The "is" of predication, identity, and existence are not separated out in the same way in this tradition. In part, this is because they were seen as deeply related. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Right. I'm glad you saw this on your own.

Given the view that things just are their properties (which are relational), a not unpopular view in contemporary metaphysics, the the sum total of what can be predicated of a thing is its identity, or at least something very close to it. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Right. See the paper I linked earlier, "Schopenhauer and Wittgenstein on Self and Object," for an argument that Fregian logic is unable to capture ontological dynamism.

In such a view, there is no Porphyryean tree that has infinite and finite being alongside each other. — Count Timothy von Icarus

It should perhaps be noted that analogical predication (or also analogical being) cannot be captured by anything like a Venn diagram. To say that two kinds of being are equivocal is to separate them, and to say that two kinds of being are univocal is to collapse them into one. Analogy is the strange mean. I said more on this earlier in the thread. -

Leontiskos

5.6kConceptual relativism on stilts. Which honestly I'm not absolutely against (unlike both Banno and @Leontiskos) but I'm unsympathetic with the whole approach and nothing I've read was at all persuasive. — Srap Tasmaner

Leontiskos

5.6kConceptual relativism on stilts. Which honestly I'm not absolutely against (unlike both Banno and @Leontiskos) but I'm unsympathetic with the whole approach and nothing I've read was at all persuasive. — Srap Tasmaner

I've changed my mind a bit, and now no longer deem this debate a waste of time. I also better see why @J is interested in this topic. I wish I had looked at Sider's paper earlier.

"Quantifier variance" is the logical instantiation of the pluralism that the West struggles with culturally, religiously, morally, et al. The "principle of charity" is the newest version of the Enlightenment's doctrine of optimism, "Stop fighting wars over religion. The disputes probably aren't that important." The aversion to disagreement is a child of the aversion to wars, and "charity" is just a mask for "peace." All of this has simply been funneled down into the field of logic. Or so I say.

So I agree that the ideas are dumb, but the motivations are intelligible and they are not going away anytime soon. If logic can overcome "relativism on stilts" then all the better, but I obviously prefer Sider's more robust approach to Finn and Bueno's (or Banno's) flatfooted approach. I wouldn't say that logic is the last line of defense, but if we can't even avoid relativism when it comes to logic then we're probably too far gone. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

The debates about univocity of being can apply between parties or within the thought of a single party, but quantifier variance occurs between two parties using two different notions of quantification. If the two parties have five different sub-quantifiers, and they agree on all of them, then quantifier variance is not occurring. ...All of this is also reminiscent of the duplex veritas debates of the Middle Ages.

:up: yeah, you're right. I wrote that during a bout of insomnia. My thinking was, if you assume QV, then when people who embrace those sorts of systems have disagreements, in a way, QV seems to assume that they are either wrong in their metaphysics or else not saying what they are saying. So the original example I thought of was comparing something like the classical Christian tradition to Shankara. In ways, the conception of infinite being is similar, but Shankara denies the existence of finite being, it being entirely maya—illusion. If QV is maintained by a third party, it seems like they can't take either of these claims in the way they are intended, which doesn't seem charitable.

I had a similar discussion with Joshs re truth being true withing a given metaphysics versus being true universally. It seems to me that if you tell a lot of people, "yes, what you're saying is true...but only in your context," you're actually telling them that what they think is false, because they don't think the truth is context dependent in this way.

What I would say is that the bolded part leads to a more thoroughgoing conceptual relativism, but the latter option is still a form of conceptual relativism. It's just that in the latter case both candidate meanings do a good job, and an equally good job, of carving at the joints.

I guess my intuition, which might very well be wrong, was that if they do an equally good job then there would be an morphism between them, and so it's pluralism of a limited type—perhaps the way some models for computation end up equivalent. -

Leontiskos

5.6kMy thinking was, if you assume QV, then when people who embrace those sorts of systems have disagreements, in a way, QV seems to assume that they are either wrong in their metaphysics or else not saying what they are saying. So the original example I thought of was comparing something like the classical Christian tradition to Shankara. In ways, the conception of infinite being is similar, but Shankara denies the existence of finite being, it being entirely maya—illusion. If QV is maintained by a third party, it seems like they can't take either of these claims in the way they are intended, which doesn't seem charitable. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Leontiskos

5.6kMy thinking was, if you assume QV, then when people who embrace those sorts of systems have disagreements, in a way, QV seems to assume that they are either wrong in their metaphysics or else not saying what they are saying. So the original example I thought of was comparing something like the classical Christian tradition to Shankara. In ways, the conception of infinite being is similar, but Shankara denies the existence of finite being, it being entirely maya—illusion. If QV is maintained by a third party, it seems like they can't take either of these claims in the way they are intended, which doesn't seem charitable. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, I agree with all of this. Earlier I said something similar:

It is to ignore the possibility that one person might be right and the other might be wrong about what they are intending to claim. This is another instance of the sort of relativism that Nagel generally opposes in The Last Word, for the legitimacy of the two philosophers' first-order arguments are precisely what is being dismissed when one thinks it could only be a conceptual or terminological dispute. Conceptual-or-terminological is a second-order reduction. — Leontiskos

As above, I think what is at stake is peace, not charity. The way that "charity" gets misused in these ways is a pet peeve of mine. Of justice, faith, and charity, only one is blind, not all three. :razz:

I had a similar discussion with Joshs re truth being true withing a given metaphysics versus being true universally. It seems to me that if you tell a lot of people, "yes, what you're saying is true...but only in your context," you're actually telling them that what they think is false, because they don't think the truth is context dependent in this way. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Right. It is to ignore the fact that the person was not intending to make a context-dependent truth claim. This relates to the edit I made to my last post to you regarding Sider's "hostile translations." Duplex veritas arose because there were multiple conflicting sources of truth (e.g. theology, philosophy, science, etc.). It arises in our culture for the same reason, except the conflicting sources are individuals, for individuals have now been made to be sources of truth in their own right. "To each their own truth."

I guess my intuition, which might very well be wrong, was that if they do an equally good job then there would be an morphism between them, and so it's pluralism of a limited type—perhaps the way some models for computation end up equivalent. — Count Timothy von Icarus

This seems likely, and perhaps in this case the "principle of charity" makes more sense (because translation is legitimately possible). Still, if translation is possible then it could be determined—even by the parties themselves—that the two parties are saying the same thing without resorting to a "principle of charity." -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

I'm not quite against conceptual relativism. You might recall my fascination with Midgley, who emphasises the difference between various conversations, ways of speaking, in her essays - her evisceration of the scientism of Dawkins, her defence of personal identity and free will and so on. I pointed to one form of relativism earlier in this thread, where a bowl of berries contains strawberries and blackberries at breakfast, but bananas and grapes in the botany class.Conceptual relativism on stilts. Which honestly I'm not absolutely against (unlike both Banno and @Leontiskos) but I'm unsympathetic with the whole approach and nothing I've read was at all persuasive. — Srap Tasmaner

Language is extraordinarily flexible. With some care we can trace paths and find patterns. But we can also make sense of A Nice Derangement of Epitaphs. "We must give up the idea of a clearly defined shared structure which language-users acquire and then apply to cases", as Davidson shows.

Language is not algorithmic, nor will it ever be complete. There cannot be a "maximal quantifier", a language that talks about everything, without sacrificing consistency. But this is not a problem since we can differentiate between breakfast and botany. We avoid the inanity of insisting that one use of "berries" is the correct use.

Th thread should have finished there. Logic does not have ontological implications.I don't think quantifiers have much of anything to do with existence or being or any of that. — Srap Tasmaner

But here we are. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

I would say it is generally taking arguments in the strongest, most compelling sense possible. However, if one starts to think that the most compelling sense of the arguments is to take them as fictions or games, when they are clearly not intended to be, it seems to go off the rails, no longer fulfilling its intended function. Foisting pluralism onto anti-pluralist positions sort of ignores what the non-pluralist is actually saying.

This is why I don't think Davidson's formulation is at all appropriate without plenty of caveats. Taken to an extreme, you can "maximize agreement," by simply taking everyone you disagree with as presenting artistic fictions. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kA priest and a vicar, old friends, were having yet another argument about theology. Finally, the priest said, "Why do we argue like this?" "When you think about it," replied the vicar, "We're both working for the same guy." "Exactly my point," said the priest, "So how about this: you go forth, and you teach His teachings in your way, and I'll go forth, and I'll teach His teachings in His."

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kA priest and a vicar, old friends, were having yet another argument about theology. Finally, the priest said, "Why do we argue like this?" "When you think about it," replied the vicar, "We're both working for the same guy." "Exactly my point," said the priest, "So how about this: you go forth, and you teach His teachings in your way, and I'll go forth, and I'll teach His teachings in His." -

Apustimelogist

946Well for one, an explanation of the words "dog" or "swimming," seems like it should require reference to dogs and water respectively, rather than just neurons. Explanations that draw a line around the brain seem to forget that brains do not work in isolation and do not produce consciousness in isolation. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Apustimelogist

946Well for one, an explanation of the words "dog" or "swimming," seems like it should require reference to dogs and water respectively, rather than just neurons. Explanations that draw a line around the brain seem to forget that brains do not work in isolation and do not produce consciousness in isolation. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Hmm, I don't think anyone could create any kind of explanations for language or the use of words without including what words are referring to or connected to - that wouldn't make sense! I don't think many people are that reductive. Similar I think can be said for other questions you talk about like the why and how word use is created. I think word use is more or less about the contexts that surround the utterance and reception of words (maybe counterfactually), whether you want to talk about context in terms of experiences or the role of the brain and physical interactions with external stuff (at least in principle). I think the questions of why and how is just a matter of expanding these contexts, the chains of causes.

I get the impression you won't disagree with what I say and maybe you have been just attacking this truncated version of use you briefly mentioned which is not intuitive to me. -

Banno

30.6kWell said.

Banno

30.6kWell said.

Consider;

Suppose the target language involves contradictions: a phenomenon all too common among anthropologists and that Evans-Pritchard faced when studying the Azande in Africa. The very idea of a proper translation would require one to preserve the inconsistencies when translating the target language into the home language. Otherwise, rather than translating the target discourse, one would be amending, correcting, and distorting it. — Quantifier Variance Dissolved

Would it be more charitable to keep or remove the inconsistencies? On the account you gave, it would be best to remove the inconsistencies.

It's not always an argument that is being translated. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Logic does not have ontological implications.

To be fair, is this obvious? I think for most "naturalists," there is going to be a path between "how the world is," and "what exists" and human logic. For those who embrace the computational theory of mind, which is still fairly dominant, parallel stepwise logical operations are what philosophy, human logic, language, and perception all emerge from. For those that buy into theories that explain physics in terms of computation, the universe is a sort of quantum computer.

And then for other schools the link is close too. For ontic structural realism, the world is a sort of mathematical object. For Hegelians, ontology is the objective logic. For much of the classical tradition, Logos is key to explaining "what there is."

For my part, I've always understood full deflation and anti-realism much more than any sort of split. I can see where these guys are coming from. I have never been able to fully wrap my mind around "splits" that involve naturalism with scientific realism on the one hand, but then full deflation on the other (i.e. truth as defined by games, or games as wholly intelligible in isolation from the world). To my mind at least, the scientific realism seems to suggest both an explication of the evolution of human logic and the idea that the formalizations of science really do "carve up the world at the joints."

But I do know a lot of naturalists still maintain a sort of Kantian dualism that allows for this sort of split

I don't think many people arethat reductive.

Well, IME, they certainly can be, but they tend to be reductive while embracing a different school of philosophy, where logic and language ultimately are reducible to particle physics—eliminitive materialism and all.

I get the impression you won't disagree with what I say and maybe you have been just attacking this truncated version of use you briefly mentioned which is not intuitive to me.

Yeah, I think the insight that meaning comes from use is a stellar one. The issue is, like you said, truncation, what counts as "use." Maybe it's just the stuff I've read, but some of it seems very behaviorist, a sort of arch empiricism where subjective experience can't be part of explanations because it cannot be objectively observed. As another sort of example, from a guy I like on a lot of things, but who seems to have a truncated view of use there is Rorty. I don't have any qualms with his attack on certain notions objectivity, but rather the claim that it is impossible to ever see how language "hooks on to the world," because of how it is bound up in social practice. Sellars on how facts are bound up in language might be another one. -

Leontiskos

5.6kTo be fair, is this obvious? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Leontiskos

5.6kTo be fair, is this obvious? — Count Timothy von Icarus

It is obviously false. As already noted, if logic had no ontological implications then there could be no historical progression in logic vis-a-vis ontology, there could be no better or worse logics vis-a-vis ontology, and Wittgenstein's logic could not have excluded dynamism from his ontology, <which it did>. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Well, yes. First order predicate calculus does not render ontological conclusions.To be fair, is this obvious? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Be charitable here.

:grin:It is obviously false. — Leontiskos

Seems we are getting to the real point of disagreement. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kThe aversion to disagreement is a child of the aversion to wars, and "charity" is just a mask for "peace." — Leontiskos

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kThe aversion to disagreement is a child of the aversion to wars, and "charity" is just a mask for "peace." — Leontiskos

I wouldn't say that logic is the last line of defense, but if we can't even avoid relativism when it comes to logic then we're probably too far gone. — Leontiskos

I've posted this before but here it is again:

There's a touching passage in Tarski's little Introduction to Logic that I'll quote in full here:

I shall be very happy if this book contributes to the wider diffusion of logical knowledge. The course of historical events has assembled in this country the most eminent representatives of contemporary logic, and has thus created here especially favorable conditions for the development of logical thought. These favorable conditions can, of course, be easily overbalanced by other and more powerful factors. It is obvious that the future of logic, as well as of all theoretical science, depends essentially upon normalizing the political and social relations of mankind, and thus upon a factor which is beyond the control of professional scholars. I have no illusions that the development of logical thought, in particular, will have a very essential effect upon the process of the normalization of human relationships; but I do believe that the wider diffusion of the knowledge of logic may contribute positively to the acceleration of this process. For, on the one hand, by making the meaning of concepts precise and uniform in its own field and by stressing the necessity of such a precision and uniformization in any other domain, logic leads to the possibility of better understanding between those who have the will to do so. And, on the other hand, by perfecting and sharpening the tools of thought, it makes men more critical--and thus makes less likely their being misled by all the pseudo-reasonings to which they are in various parts of the world incessantly exposed today.

That's Tarski writing from Harvard in 1940, having fled Poland before the German invasion. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Does any one else see this as a bad argument? @Count Timothy von Icarus? @Srap Tasmaner?if logic had no ontological implications then there could be no historical progression in logic vis-a-vis ontology, there could be no better or worse logics vis-a-vis ontology, — Leontiskos

If logic does not have ontological implications, then there are no better or worse logics regarding ontology.

But it remains that there may be better or worse uses of logic in ontological arguments.

Or is there a more charitable way to read this than as a transcendental argument with a false conclusion? -

Leontiskos

5.6kI would say it is generally taking arguments in the strongest, most compelling sense possible. However, if one starts to think that the most compelling sense of the arguments is to take them as... — Count Timothy von Icarus

Leontiskos

5.6kI would say it is generally taking arguments in the strongest, most compelling sense possible. However, if one starts to think that the most compelling sense of the arguments is to take them as... — Count Timothy von Icarus

See 's post.

For my money, so-called "principles of charity" are always destructive of intellectual honesty, even in the one or two sentences where they appear in Aquinas. At best they fail the test of Occam's Razor, and are superfluous.

Consider the popular "steelman" interpretation. Is it good to steelman someone's argument when you are dialoguing with them? No, actually. You should try to interpret them accurately, neither engaging in "strawman" or "steelman." One does not need to appeal to "charity" to preclude advantageous misrepresentation.

Now, if one is not in a dialogue context but is instead reading an unfamiliar author, then I would say that one should give them the benefit of the doubt, ceteris paribus. This is a kind of charity, but I would say that it is more accurately a kind of maximization of the philosophical activity. If you are exploring ideas, then you should desire to explore the strongest ideas and arguments, for the sake of this activity.

I would say that charity pertains to the practical realm, and it influences speculative reason only indirectly, through the practical reason. For the understanding of the speculative reason, it is a non-starter.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Difference(s) between ontological commitment, a priori claims, and empirical claims

- Confusing ontological materialism and methodological materialism complicates discussions here

- Sometimes, girls, work banter really is just harmless fun — and it’s all about common sense

- What about an "ontological foundation" in philosophical questions?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum