-

Moliere

6.5kThat's just what a definition is. — Leontiskos

Moliere

6.5kThat's just what a definition is. — Leontiskos

:D

This points out a pretty big difference between our understandings, at least.

I'd say that the Oxford English Dictionary's philosophy of language requires us to be able to pick out examples in order to derive definitions.

"X is what Xers do" is a tautological and uninformative statement. — Leontiskos

But that's not my theory of science -- my theory of science isn't so general as to say that all all things like "science" are defined by the actionsofof the people involve. And even if it were so, which I doubt, a tautology is always true. "Science is what scientists do" isn't something I could say is true strictly, but rather is a criteria for class inclusion for uses of "science" or "scientist"

"Science is science" would be a tautology, but "Science is what scientists do when they are acting as scientists" isn't. (it asks the reader to add interpretation, of course -- it's a definition not looking for necessary/sufficient/universal conditions) -

ssu

9.8k

ssu

9.8k

Better even if academic journals would be available freely in the net. Think about general science magazines if they would have links to all the original publications. There's still the paywall and simply you have to somehow have to have the knowledge of an interesting article being in some publication.As a starting place maybe it'd be nice if public libraries had access to academic journals. Taxes go to pay for that research after all. It should be accessible. — Moliere -

Leontiskos

5.6kI'd say that the Oxford English Dictionary's philosophy of language requires us to be able to pick out examples in order to derive definitions. — Moliere

Leontiskos

5.6kI'd say that the Oxford English Dictionary's philosophy of language requires us to be able to pick out examples in order to derive definitions. — Moliere

There is a problem with Socrates' pet peeve of giving examples instead of explanations, and dictionaries don't generally fall into this mistake, but in fact you haven't given any examples. You are falling into a more basic mistake of using the definiens in the definiendum, something like this:

- "What is science?"

- "It's what scientists do."

- "What do scientists do?"

- "Scientists do science."

In response to an objection you added a rider that exemplified this problem:

Well as long as they are a scientist, then according to your definition whatever they are doing must be science. — Leontiskos

"Science is what scientists do when they are acting as scientists" — Moliere

If we remove the definiens terms the problem becomes even more apparent:

- "What is science?"

- "Science is what someone who does it does when they are doing it." (or)

- "Science is what someone who does it does when they are acting as someone who does it."

And even if it were so, which I doubt, a tautology is always true. "Science is what scientists do" isn't something I could say is true strictly, but rather is a criteria for class inclusion for uses of "science" or "scientist" — Moliere

This is in large part why I wrote my thread on transparency. When we do philosophy we have to take the risk of saying substantive things, even though this leaves us open to critique. -

Moliere

6.5kIf we begin with Merriam-Webster, as you've done, then "Science is what scientists do as scientists" is filled out by our common-sense understanding of these terms.

Moliere

6.5kIf we begin with Merriam-Webster, as you've done, then "Science is what scientists do as scientists" is filled out by our common-sense understanding of these terms.

I've said more than just the statement of a theory, though: Good bookkeeping, communication of results over time, humans being coming together to create knowledge, the marriage to economic activity, and a basic sense of honesty though an irrelevance for the motivation of a particular scientist. And I've referenced Newton while explicitly saying that the definition of "science" will always be vague (Newton was a scientist, so science is what Newton did as a scientist -- but if we compare other obvious examples, let's say Francis Crick, the differences between what they do are more obvious than their similarities): But we can still get by and say interesting, and somewhat general, things about science in spite of not starting from some explicit set of criteria for class inclusion. We generally know what we mean by the word, and generally know who is included -- but then when we get more specific, or try to do so, cases can fall out.

I've also said there are two explicit things I'd like a theory of science to accomplish: the demystification of process so that science is not perceived as magical, and a pedagogical simplification not for the purposes of identifying science, but for the purposes of learning how to do science: in some sense my definition of "science" is serviceable enough for those tasks, and we needn't begin at The Meaning of Being in order to say good an interesting things about the subject at hand.

And in the background of all of this thinking is the transition from verificationism to falsificationism to Quine's attack on empiricism and Feyerabend's deconstruction of all such programs: so the background, springboard question is the Question of the Criterion that Popper begins with, and my answer is that there isn't really a general theory that covers all cases, but that we can situate a more limited theory of science within a community of practitioners.

Because I don't really see a union between Aristotle and Marie Curie, for example. They're just doing different things, though it's fair to call Aristotle a scientist of his time. -

Moliere

6.5kThough there is also this other side, i think: There's something about a forum post that demands a more collaborative approach than the usual "presentation of a theory with reasons", at least from what I've seen: by overly relying upon the 20th century philosophers-of-science, for instance, I'd be ignoring other eras of science and their attendant philosophies, and I'd be looking at a particular bit of academic work -- mostly because I think that the philosophers who have tried such an enterprise before worth looking at.

Moliere

6.5kThough there is also this other side, i think: There's something about a forum post that demands a more collaborative approach than the usual "presentation of a theory with reasons", at least from what I've seen: by overly relying upon the 20th century philosophers-of-science, for instance, I'd be ignoring other eras of science and their attendant philosophies, and I'd be looking at a particular bit of academic work -- mostly because I think that the philosophers who have tried such an enterprise before worth looking at.

But here some people haven't bothered with those particular philosophers, and I don't feel like they are the end-all-be-all of philosophy of science, either, just a touchstone for me of where I'm thinking from. The brainstorming process itself, though, is more about arriving at a thesis to defend, if there indeed be such a thing in the firstplace, or even a sharing of different perspectives on how we understand the beast science -- whereas for me I'm thinking about it from the perspective of what to do in order to be valuable to the scientific project as it presently stands, I like to keep threads open to other approaches. -

Moliere

6.5kI agree.

Moliere

6.5kI agree.

The primary reasons to keep knowledge are profit and war: there is some advantage someone wants to keep.

This conflicts with the engine of knowledge-generation which requires sharing and creativity if something new, rather than procedural, is to be created -- and given that it's new there's no guarantee that it will be valuable at all.

Which is why research is jealously guarded: It takes lots of money to keep a staff that might not produce anything, and when it does you want to keep it for yourself. (though, under Capitalism, what else would you expect?) -

ssu

9.8kIf the knowledge or insight is worth money, yes. However there's still a lot of academic and scientific studies that people, who have done them, would enjoy if their ideas would be picked up by others. It's totally understandable that for example nuclear weapons technology and the science used is declared classified and you just don't sell it to anyone that wants it. With philosophy, it isn't.

ssu

9.8kIf the knowledge or insight is worth money, yes. However there's still a lot of academic and scientific studies that people, who have done them, would enjoy if their ideas would be picked up by others. It's totally understandable that for example nuclear weapons technology and the science used is declared classified and you just don't sell it to anyone that wants it. With philosophy, it isn't.

Still, I think that there is a problem when there simply are so many scientists and academic researchers, group behavior kicks in and an incentive emerges to create your own "niche" by niche construction: a group creates it's own vocabulary and own scientific jargon, which isn't open to someone that hasn't studied the area. Then these people refer to each others studies and create their own field. Another name for this could be simply specialization: you create your own area of expertize by specialization on a narrower field. When there are a masses of people doing research, this is the easy way to get to those "new" findings. Hence even people in the natural sciences can have difficulties in understanding each other, let alone then the people who are studying the human sciences. Perhaps it's simply about numbers: 30 scientists can discuss and read each others research and have a great change of ideas, but 3 000 or 30 000 cannot. Some kind of pecking order has to be created. The end result is that you do get a science that is "Kuhnian" just by the simple fact that so many people are in science.

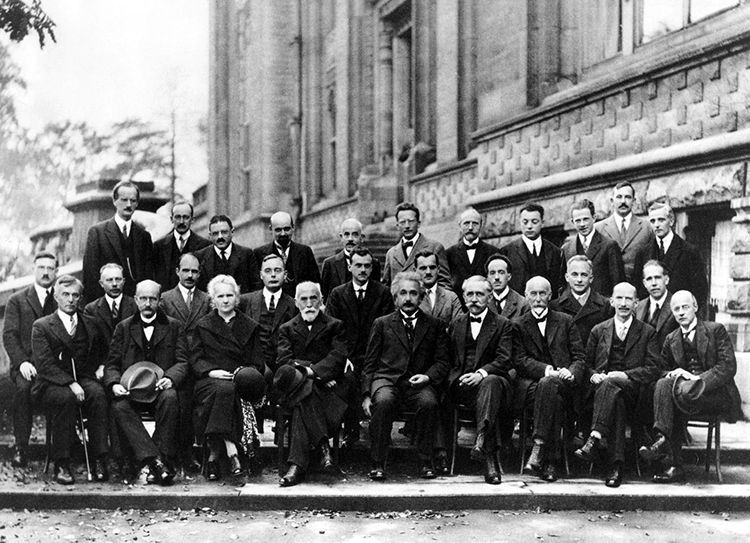

(In 1927 it was easier just with 29 quantum physicists meeting each other)

I remember when studying a course in philosophy in the university I personally got irritated when a philosophy teacher said that one could only use the German words for some philosophical terms or otherwise their "essence" would be lost (think example's like Heidegger's Dasein). Well, if you cannot translate your ideas to another language or cannot define something by using other words, there's something wrong with you. But that's just my opinion and others can disagree with this.

And this is universal and not just limited to philosophy. I remember another historian who went to great lengths to write one of her historical books to be as easily readable for the layman as she could do only then to be scolded by her peers for the book not being "academic" enough. For some to be as understandable as possible isn't the objective, the objective is to limit those who don't know the proper terms out of the discussion, even if they could participate in the discussion. Naturally people will simply argue that just like with abbreviations, we make it easier for people to read it when we use the academic jargon. But there can really be other intensions also.

(Yes, it's the length of the equation, even if mathematical beauty would say otherwise)

-

Moliere

6.5kHowever there's still a lot of academic and scientific studies that people, who have done them, would enjoy if their ideas would be picked up by others. — ssu

Moliere

6.5kHowever there's still a lot of academic and scientific studies that people, who have done them, would enjoy if their ideas would be picked up by others. — ssu

It's true -- and perhaps another way to address these issues would be a reclassification of some kind rather than the radical solution I proposed. I do think that intellectual property is a bit funny in the law now, and mostly think that such things ought to be run by the state more than private industry because, generally, they benefit everyone, like roads benefit everyone.

Still, I think that there is a problem when there simply are so many scientists and academic researchers, group behavior kicks in and an incentive emerges to create your own "niche" by niche construction: a group creates it's own vocabulary and own scientific jargon, which isn't open to someone that hasn't studied the area. Then these people refer to each others studies and create their own field. Another name for this could be simply specialization: you create your own area of expertize by specialization on a narrower field. When there are a masses of people doing research, this is the easy way to get to those "new" findings. Hence even people in the natural sciences can have difficulties in understanding each other, let alone then the people who are studying the human sciences. Perhaps it's simply about numbers: 30 scientists can discuss and read each others research and have a great change of ideas, but 3 000 or 30 000 cannot. Some kind of pecking order has to be created. The end result is that you do get a science that is "Kuhnian" just by the simple fact that so many people are in science. — ssu

It's not open to others' only because they cannot study it, due to accessibility issues.

I mean, knowledge is created, not just sitting around to be catalogued, so it will take people inventing new vocabularies as we learn more. What I think we see is that there is just that much to know that no one person can know it all. Even in switching between labs I've had to learn whole new parts of science I've never encountered before (which is part of why it's interesting)

The difficulty is more one of familiarity than anything else: scientists I've known are always pretty specific about what it is they know know -- as in their area of research -- and elsewise.

You have to be because eventually it dawns on you that there's so much knowledge out there that you can't know it all. No one could live long enough to know it all.

I'm not sure that means there's a pecking order that must be established? I think science sprawls much more widely than that -- tho normal social hierarchies that are alive in all parts of our life are still operational in the sciences, too.

I remember another historian who went to great lengths to write one of her historical books to be as easily readable for the layman as she could do only then to be scolded by her peers for the book not being "academic" enough. For some to be as understandable as possible isn't the objective, the objective is to limit those who don't know the proper terms out of the discussion, even if they could participate in the discussion. Naturally people will simply argue that just like with abbreviations, we make it easier for people to read it when we use the academic jargon. But there can really be other intensions also. — ssu

My preference is for a wider audience, generally, and I dislike the attitude people take towards works which are actually quite technical and well researched, only broken down to a point that they read very easily. That's actually harder to do than rely upon the jargon! :D

But the jargon is fine, too, because sometimes I'd agree with your philosophy professor who irked you -- you need to use the word in order to set the right sense, because philosophy -- in part -- creates its own language, and it is generated from a natural language, and those natural-language associations can have important philosophical implications.

(Yes, it's the length of the equation, even if mathematical beauty would say otherwise) — ssu

:D I don't mind. It is the lounge for a reason, even if there are some heady thoughts out there -- I really wanted to brainstorm science with this thread, as in, trip across different ideas about science that are nevertheless important. And that requires a tolerance for branching out to related subjects (and since I've barely set a theme, well... have at it!) -

Leontiskos

5.6kIf the knowledge or insight is worth money, yes. However there's still a lot of academic and scientific studies that people, who have done them, would enjoy if their ideas would be picked up by others. — ssu

Leontiskos

5.6kIf the knowledge or insight is worth money, yes. However there's still a lot of academic and scientific studies that people, who have done them, would enjoy if their ideas would be picked up by others. — ssu

I think people want to share their ideas and they want to profit by their ideas, at the same time. If the latter is not possible then philosophy is only a hobby and not a career. If all philosophy were free then philosophers would make no money.

The traditional donor system helps address this problem, but only to a point. -

Leontiskos

5.6kIf we begin with Merriam-Webster, as you've done, then "Science is what scientists do as scientists" is filled out by our common-sense understanding of these terms. — Moliere

Leontiskos

5.6kIf we begin with Merriam-Webster, as you've done, then "Science is what scientists do as scientists" is filled out by our common-sense understanding of these terms. — Moliere

The single word "science" is equally "filled out" by our understanding of the term. A definition presupposes that one does not understand the term.

I've said more than just the statement of a theory, though: Good bookkeeping, communication of results over time, humans being coming together to create knowledge, the marriage to economic activity, and a basic sense of honesty — Moliere

Sure, but none of these pick out science in particular. For example, this describes an honest law firm as much as it describes anything else.

We generally know what we mean by the word, and generally know who is included — Moliere

I want to say that if we generally know what we mean by a term then we will be able to give a definition, and if we can't give a definition then we probably don't know what we mean by a term.

I've also said there are two explicit things I'd like a theory of science to accomplish: the demystification of process so that science is not perceived as magical, and a pedagogical simplification not for the purposes of identifying science, but for the purposes of learning how to do science: in some sense my definition of "science" is serviceable enough for those tasks, and we needn't begin at The Meaning of Being in order to say good an interesting things about the subject at hand. — Moliere

It seems to me that your "accounts" of science are very much in line with the magical thinking of the culture. We don't really know what science is, but we revere it and generate overly robust or overly simplistic conceptions of it. Is it demystifying to say that scientists do bookkeeping? Hmm, I don't know. "Bookkeeping" is a very ambiguous term, and the ambiguity lends credence to the idea that you might be saying something very substantial. "Scientists type in computers," "Scientists read literature," "Scientists test theories." These are all true facts about scientists, but we don't know which of them is telling us anything that is actually connected with science in itself without a definition.

And if someone doesn't have a definition of science then I'm not sure how they could be trusted to teach others how to do science. A pedagogue must understand what he is teaching.

The brainstorming process itself, though, is more about arriving at a thesis to defend, if there indeed be such a thing in the firstplace, or even a sharing of different perspectives on how we understand the beast science -- whereas for me I'm thinking about it from the perspective of what to do in order to be valuable to the scientific project as it presently stands... — Moliere

I want to say that a scientist is ultimately interested in understanding the natural world, and he does things that achieve that end. I think science is just the study of the natural world and the ordered body of knowledge that this generates.

As a philosopher I would agree with Feser and say that many "scientists" do not understand science, and because of this it is wrong to define science in terms of their work. For example, we could inquire about a cathedral like Chartres and its architecture. Someone might say, "The architecture of Chartres is what the builders did." Except this is confused, for what the builders ultimately did was take orders from the head architect, and when the head architect died the selection process was very protracted: you don't just entrust Chartres to any old builder.

That is I'm taking up a historical-empirical lens to the question -- the philosophical theory is "Science is what scientists do", which, of course, is defined only ostensively and so doesn't have some criteria for inclusion. — Moliere

We know that it has implicit criteria for inclusion given the fact that you qualify it every time it produces a false conclusion, such as in the case of Fauci or in the case of scientists who are not properly "acting as scientists."

Aristotelian definition in the broad sense is not something you can do without. If you say, "Grass is whatever grows here in the next five years," and a tree grows there in the next five years, then that tree is grass, which is absurd. In light of the tree someone might emend their claim and say, "Grass is whatever grows here in the next five years, such that it looks and behaves like grass does." But this is the vacuous, viciously circular sort of claim. "Any grass that grows here in the next five years is grass."

Note too that real definitions are actually falsifiable. Someone can say, "Ah, but Leontiskos, computer scientists are scientists who do not study the natural world." At such a point I would not be allowed to give a non-answer about how my definition was not intended to be a definition. (And there is a healthy debate about whether "computer science" is aptly named.) The centrality of falsifiability is something that science and philosophy share, albeit in different ways. -

Moliere

6.5kSure, but none of these pick out science in particular. For example, this describes an honest law firm as much as it describes anything else. — Leontiskos

Moliere

6.5kSure, but none of these pick out science in particular. For example, this describes an honest law firm as much as it describes anything else. — Leontiskos

No definition picks out anything in particular: gavagai could refer to the foot, the meat, the ear, or the weather in which one catches a rabbit. And the use of "gavagai" in a particular circumstance could refer to a philosopher's idea about translation and reference.

Definitions don't pick things out at all, nor do they presuppose total ignorance: sometimes I just want to know what is usually meant by a word, which is where dictionaries excel.

I'm thinking this notion of definition, the place of the categories, whether reference is accomplished through knowledge of predicates of the thing or activity, is a disagreement.

I want to say that a scientist is ultimately interested in understanding the natural world, and he does things that achieve that end — Leontiskos

I'm hesitant to say "the natural world", and I don't think there's a real end to science in the general sense -- across all time and space, ala Aristotle compared to Curie -- but I agree with the basic thrust of this statement, especially if I were talking to someone who knew nothing. I am thinking a little more above that in my brainstorm, for sure. I'm thinking about method and teaching method.

I don't think a scientist needs to want to understand the natural world as a whole, as Aristotle does. If someone wants to study cancer because someone they care about has cancer and that's all they focus upon while doing good science then they are a scientist. They care about the truth of cancer, but all the trappings of a "natural world" or wholeness are not there. They want to cure a disease through science and do science in order to get there.

Or no, in your estimation?

We know that it has implicit criteria for inclusion given the fact that you qualify it every time it produces a false conclusion, such as in the case of Fauci or in the case of scientists who are not properly "acting as scientists." — Leontiskos

Fauci is too political example for this thread.

But what is related: I don't agree with the notion that we should "trust" scientists -- the whole idea here being that others' can evaluate things for themselves so they don't have to take their word for it but see it themselves. This isn't to say anything about Fauci's acts, which I've barely paid attention to and don't really feel like digging into because to defend him as an upstanding scientist would go against this whole idea that I'm thinking through.

I don't care if some individual scientist fucked up, or if there's some reason why the public doesn't trust scientists (they shouldn't have trusted anything they read in a newspaper, if you ask me): I care about teaching others how to evaluate science and, if they so wish, do good science.

Basically I'm not interested in defending the "mantle" of science because I don't really believe in "experts" in the social sense anyways. There are people who are better able to do this or that, of course, but "experts" presupposes a lot more than ability -- it's a whole ass meritocracy complete with packages to judge people with.

Which, you may have picked up, is not my thing so much ;)

Aristotelian definition in the broad sense is not something you can do without. — Leontiskos

:D

But that's what I'm trying to do!

I'm being explicit about it at least. -

Moliere

6.5kAlso:

Moliere

6.5kAlso:

One of the things I've noticed is how scientists range the gamut in metaphysical beliefs. Yet I trust them to do good science. So I conclude that metaphysical beliefs will not influence whether a person does good science or no -- and that's what I'm most interested in.

(EDIT: Well... "most"? No, just a point I like to bring up: I've learned from people of many faiths, and hence, many metaphysics. One of the things that I like about science is its ability to unite people from many backgrounds into international efforts.

Scientifically speaking it seems all metaphysics are valuable, rather than just one) -

Leontiskos

5.6kI don't think a scientist needs to want to understand the natural world as a whole — Moliere

Leontiskos

5.6kI don't think a scientist needs to want to understand the natural world as a whole — Moliere

Sure, and that's not what I was saying. A scientist need not be interested in the whole of the natural world to be interested in the natural world.

No definition picks out anything in particular...

...

Definitions don't pick things out at all... — Moliere

I'm not really sure where to start with these sorts of claims. Do words pick out anything at all? It would seem that we are back to Aristotle's defense of the PNC in Metaphysics IV.

If "science" doesn't mean anything at all then we obviously can know nothing about science. If "science" does not pick out anything in particular, then it would seem that we can't use the word meaningfully. You seem to almost be doubling-down on your circular definitions in claiming that definitions don't pick out anything. -

ssu

9.8k

ssu

9.8k

And this is all it is, actually. After reading Thomas Kuhn's work I found it perplexing how someone could see it as something revolutionary or something that would be tarnish the shining shield of science. The simple fact that people in groups behave as people in groups. Yet this doesn't make science itself something else, a totally "social construct" as some wrongly think.- tho normal social hierarchies that are alive in all parts of our life are still operational in the sciences, too. — Moliere

I think there's no reason to have this in the lounge... this is an open Philosophy Forum and hence the threads in the first page aren't so different from this in the end.:D I don't mind. It is the lounge for a reason, even if there are some heady thoughts out there -- I really wanted to brainstorm science with this thread, as in, trip across different ideas about science that are nevertheless important. And that requires a tolerance for branching out to related subjects (and since I've barely set a theme, well... have at it!) — Moliere

An interesting question is if science will change, or will it be rather similar to what we have now even in the distant future, let's say 200 years from now in 2224. Now we can see very well where science was in 1824, just on this verge of a huge sprint that was taken in the late 19th Century and in the 20th Century. Yet in 1824, what typically was taught in the universities of the time and what was publicly known might be different than we think now. But how close science in 2224 to science in 2024? The more similar it is, I think it's more depressing as one would hope that astonishing new ideas would come around.

But will they? -

Moliere

6.5kSure, and that's not what I was saying. A scientist need not be interested in the whole of the natural world to be interested in the natural world. — Leontiskos

Moliere

6.5kSure, and that's not what I was saying. A scientist need not be interested in the whole of the natural world to be interested in the natural world. — Leontiskos

Are appeals to "natural world" any less ambiguous than appeals to "scientific method"?

There's a sidetrail to metaphysics I see, but then it could just be this substitutes one mystery for another: "What is the natural world?" for "What is the criterion which differentiates scientific knowledge?" being a metaphysical and an epistemic question, respectively.

I'm not really sure where to start with these sorts of claims. Do words pick out anything at all? — Leontiskos

Names pick things out -- that's what we're doing with them! (it could be argued this is analytic, even.... so whether they really pick things out, well, who knows? How do you tell?)

It would seem that we are back to Aristotle's defense of the PNC in Metaphysics IV. — Leontiskos

I don't think so. I'd rather say that's a different topic entirely. I don't see any violations of that rule going on, at least. -

Moliere

6.5kI think there's no reason to have this in the lounge... this is an open Philosophy Forum and hence the threads in the first page aren't so different from this in the end. — ssu

Moliere

6.5kI think there's no reason to have this in the lounge... this is an open Philosophy Forum and hence the threads in the first page aren't so different from this in the end. — ssu

I've been thinking through these aesthetics and ultimately what I've been doing with my threads is if there's just a kinda sorta thing going on that I'm thinking about but I don't really have a thesis I'll put it here as a sketch which isn't quite a post, even if there's some interesting stuff going along (else, why post it at all?)

But if I have some text or thesis or question that I want to explore to either aporia, uncertainty, or maybe an answer then I post it in a main forum.

An interesting question is if science will change, or will it be rather similar to what we have now even in the distant future, let's say 200 years from now in 2224. Now we can see very well where science was in 1824, just on this verge of a huge sprint that was taken in the late 19th Century and in the 20th Century. Yet in 1824, what typically was taught in the universities of the time and what was publicly known might be different than we think now. But how close science in 2224 to science in 2024? The more similar it is, I think it's more depressing as one would hope that astonishing new ideas would come around.

But will they? — ssu

They will. People are creative sorts, when enabled.

And as the economy changes the human practices that are a part of it will too. And the economy is never stable, so science will continue to change. -

Moliere

6.5kThe metaphysical path I see is one which would be just as confusing as a methodological path, given that "nature" -- in description -- has changed with scientific knowledge and vice-versa; since there are different descriptions of nature. From what do we separate nature so that we know that the scientist is studying nature, and not some other metaphysical kind?

Moliere

6.5kThe metaphysical path I see is one which would be just as confusing as a methodological path, given that "nature" -- in description -- has changed with scientific knowledge and vice-versa; since there are different descriptions of nature. From what do we separate nature so that we know that the scientist is studying nature, and not some other metaphysical kind?

Also, there's a fear I see that I'd just get lost in the metaphysical question when the point is to demystify what we're doing and how we're doing it -- but metaphysics has a tendency to get mystical, so it might even go cross-purposes to what I'm thinking through.

One of the things that'd have to be worked out is how it is that scientists of different metaphysical beliefs can work together? My thought on this is that since there are theists, atheists, naturalists, and anti-realists -- and shades in-between (what is the status of consciousness?) -- that all can work together and agree upon the science that there is a difference between metaphysical belief and science. That is, there is no need to have a secure foundation in metaphysics to do good science when we look at people who do science.

In a lot of ways my criteria is mostly a meta-criteria for examples. What is science? Start with observations of scientists -- it turns it from a metaphysical question to a historical one. (or, in the case of Popper, from a normative question addressing the problem of induction, to a historical one) -

ssu

9.8k

ssu

9.8k

That's a similar conclusion I've made too.And as the economy changes the human practices that are a part of it will too. And the economy is never stable, so science will continue to change. — Moliere

Basically when humanity has to adapt to the post-Peak population era with falling populations all over the World, a lot more than just economics with models of perpetual growth have to be changed. It's not just economics: social sciences have to adapt to explain the new situation. Just like the research on infectious diseases have to adapt to the new diseases that simply show up. (If there aren't any, at least you always have a lab leak!)

Perhaps the real question is sciences like Physics, Chemistry or even Philosophy in general.

But great that you are optimistic! :) -

Moliere

6.5kPerhaps the real question is sciences like Physics, Chemistry or even Philosophy in general. — ssu

Moliere

6.5kPerhaps the real question is sciences like Physics, Chemistry or even Philosophy in general. — ssu

I believe these will adapt in a similar fashion. That is, I don't see them as "complete" at all.

One of the reasons I hesitate to pair science with metaphysics is metaphysics seeks a more complete story than the sciences tell. If scientific knowledge is the only basis for metaphysical belief then the only metaphysical belief we could reasonably hold is "I suppose we'll have to wait and see"

Further, while I believe the sciences are true, and even describe real phenomena, I believe they are always in some sense anthropocentric too: these are the parts of reality we're interested in articulating (or, perhaps at the time, able).

It's not like Isaac Newton's calculus applied to physics was purely a matter of looking at nature -- it also helped build better cannons (and so on): Being able to predict the motion of bodies is interesting to us because it can help with so many other things we want to accomplish.

But great that you are optimistic! :) — ssu

Oh, I dare not say that. If we do it bad enough I think these changes will come about painfully, given that the fear of death is still a popular motivator.

And the severity could still be cruel for all that, even though new ideas will come about. -

jorndoe

4.2kI'm thinking that scientific methodologies are a means for models to converge on evidence/observations.

jorndoe

4.2kI'm thinking that scientific methodologies are a means for models to converge on evidence/observations.

The models are revisable/adjustable and falsifiable (in principle always tentative/provisional).

So, in a way, sufficiently stabilized/usable models become parts of scientific theories, where "sufficiently" means within some domain of applicability or category of evidence/observations.

That may seem overly depreciative/critical, yet science remains the single most successful epistemic endeavor in all of human history bar none, and doesn't carry any promise of omniscience — the forums depend on science.

Doesn't science more or less take the role of "justified" in knowledge as justified true belief? -

Moliere

6.5kDoesn't science more or less take the role of "justified" in knowledge as justified true belief? — jorndoe

Moliere

6.5kDoesn't science more or less take the role of "justified" in knowledge as justified true belief? — jorndoe

I don't think so because justified true belief can be much wider than science. Why do I believe it rained? The ground is wet -- it's not exactly a scientific justification, at least in the sense of doing good science (though perhaps in the sense of making empirical inferences -- which I think is too broad; the example I like, which I stole from Massimo Pigliucci, is plumbing -- it's a technical empirical body of knowledge which predicts and models the world which is subject to revision, but it's not science)

Also I'd say that some science is true, so there's more to science than "justified"

That may seem overly depreciative/critical, yet science remains the single most successful epistemic endeavor in all of human history bar none, and doesn't carry any promise of omniscience — the forums depend on science. — jorndoe

Heh, I welcome being critical -- I'm not sure it's the single most successful epistemic endeavor, either. I'm not sure how one measures something like that. What are the units for epistemic success?

I'm thinking that scientific methodologies are a means for models to converge on evidence/observations.

The models are revisable/adjustable and falsifiable (in principle always tentative/provisional).

So, in a way, sufficiently stabilized/usable models become parts of scientific theories, where "sufficiently" means within some domain of applicability or category of evidence/observations. — jorndoe

Can you give an example of a scientific methodology? it'd help me parse this better. -

jorndoe

4.2kjustified true belief can be much wider than science — Moliere

jorndoe

4.2kjustified true belief can be much wider than science — Moliere

Sure, make it ...

Doesn'tCan't science more or less takethea role of "justified" in knowledge as justified true belief? — Aug 13, 2024

an example — Moliere

I think this might be a sort of standard example from physics:

Aristotle looks around, comes up with a theory of motion → Galileo looks around some more, tests, comes up with better theories → Newton thinks things over, observes, advances/generalizes theories (used to this day) → Einstein, having access to more, improves theories, more complex, used by GPS

The models adapt to accumulating evidence/observations if you will. Might be worth noting that the methodologies became more evidence/observation-driven/dependent, say, in the 1600s. Model-falsifiability is a must these days.

Well, science can redo conventional wisdom, make something counter-intuitive acceptable, and help put rovers and stuff on Mars. :)

With something like sociology or psychology (about ourselves), things become more complicated, and we may have to contend with less accurate/stable theories. -

Moliere

6.5kSure, make it ...

Moliere

6.5kSure, make it ...

Can't science more or less take a role of "justified" in knowledge as justified true belief?

— Aug 13, 2024 — jorndoe

Ah OK; I think we need to say more about science to make it it's own thing different from philosophy, but I think I'd be fine with saying that science is largely concerned with justification.

falsifiable (in principle always tentative/provisional). — jorndoe

I think of falsifiability much in the frame of Popper, which requires much more than merely being always tentative/provisional.

For instance -- I don't think that the first law of thermodynamics is strictly falsifiable, unless you encounter magic (literally getting energy for free). It's more of an accounting mechanism to force the ape to figure out why the numbers don't match.

But surely it's still provisional for all that -- if we find a better way we will abandon this way of accounting for energy transfers. But if we already knew that better way we'd already be there -- it's more that we could always encounter more, or reinterpret differently in productive ways (whatever our future species might like)

The models adapt to accumulating evidence/observations if you will. Might be worth noting that the methodologies became more evidence/observation-driven/dependent, say, in the 1600s. Model-falsifiability is a must these days. — jorndoe

I'm not comfortable with this use of "model", exactly -- there are times when "model" works, like when I build a model of a molecule out of balls and sticks to show its accepted structure in 3D space for students to learn. Or if I have a plan and I build a small version of the plan. Or if I have a proof of concept that it will work. Or medically I can have a model organism -- like a mouse or yeast -- to demonstrate the efficacy of some biochemically similar organism's reaction to a cure for cancer to test some halfway house to see if it will interrupt similar pathways and lead to death before putting it in humans, rather than a guess based on the description of the chemical network.

I'm not sure that Newton's Laws are a model. I think models are supposed to reflect something else -- they are models-of. What are Newton's Laws a model of? (All mechanics or nature is the original implication, but surely at this point we can see that we have enough exceptions that it's not UNIVERSAL universal, but pretty good)

Well, science can redo conventional wisdom, make something counter-intuitive acceptable, and help put rovers and stuff on Mars. :) — jorndoe

Yeh.

With something like sociology or psychology (about ourselves), things become more complicated, and we may have to contend with less accurate/stable theories. — jorndoe

Is that the only difference, in your estimation, between the so-called "hard" and "soft" sciences? -

Moliere

6.5kTyping this out from The Logic of Scientific Discovery

Moliere

6.5kTyping this out from The Logic of Scientific Discovery

5. EXPERIENCE AS METHOD

The task of formulating an acceptable definition of the idea of an 'empirical science' is not without its difficulties. Some of these arise from the fact that there must be many theoretical systems with a logical structure very similar to the one which at any particular time is the accepted system of empirical science. This situation is sometimes described by saying that there is a great number-- presumably an infinite number -- of 'logically possible worlds'. Yet the system called 'empirical science' is intended to represent only one world: the 'real world' or the 'world of our experience'

I'm just flipping through to try and give some footholds in Popper, and liked the title of this section because it seems to get along with what I think.

There is more, which I'd have to revisit to get more clear, about observation vs. theoretical statements, or basic statements, which I think all goes down the dumpster when you look at the the publications of scientists. (Maybe one of the reasons I don't remember it ;) :P) -

Leontiskos

5.6kAre appeals to "natural world" any less ambiguous than appeals to "scientific method"? — Moliere

Leontiskos

5.6kAre appeals to "natural world" any less ambiguous than appeals to "scientific method"? — Moliere

I think the latter appeal is less ambiguous than the former, but both would seem to be less ambiguous than the descriptions you have been giving.

One of the things that'd have to be worked out is how it is that scientists of different metaphysical beliefs can work together? — Moliere

I think what you're missing is that, in large part, they can't. The metaphysical differences between the groups you are identifying are accidental qua science. There are some metaphysics which are compatible with science and some which are not. It is an invalid argument to identify a few which are compatible and then claim that metaphysics is tangential to science. For example, science at least presupposes things like causal regularities, the intelligibility of reality, and the human mind's ability to know it. When Aristotle rejects Parmenides and Heraclitus he paves the metaphysics of science.

I think what we can draw from this thread is that people very seldom have any clear idea of what they mean by "science." If we literally applied a Wittgenstenian language-as-use approach, "science" would probably be the name of a modern god who is invoked in important questions, and who must be trusted. The creedal statement is, "I trust the science," and there is no clear referent for what "the science" is supposed to point to. -

jorndoe

4.2kI don't think that the first law of thermodynamics is strictly falsifiable — Moliere

jorndoe

4.2kI don't think that the first law of thermodynamics is strictly falsifiable — Moliere

Right. Would the zero-energy universe violate conservation?

It's falsifiable, though, but maybe it won't ever be. In a way, the fluctuation theorem disproves strict entropy.1 - 1 = 0 ↑ \ we're here

Evidence as proof

I take proof to be deductive, as found in logic and mathematics. I'm seeing two cases where evidence is proof:

• a particular existential claim ("here's a stampeding elephant")

• a counter-example to a general/universal claim ("here's a black swan")

(also check here)

These correspond to proving a ∃x∈S φx proposition, and disproving a ∀x∈S φx proposition, respectively.

(∃) "there are extraterrestrial aliens", "the Vedic Shiva is real", ..., showing is proof

(∀) "photons don't decay", "all life is DNA based", ..., showing a counter-example is disproof

Outside of such proofs, scientific methodologies aren't proofs, but (more or less) means by which to develop general claims inferred from particular existential claims. Naturally, this characterization is a bit rigid, and, as usual, there are all kinds of details.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum