-

NOS4A2

10.2kI recently read an article in Nature magazine in which researchers plead to their readers that we ought to care more about the threat of misinformation to democracy. To illustrate the threat they provide the typical examples, “false claims about climate change, the efficacy of proven public-health measures, and the ‘big lie’ about the 2020 US presidential election have all had clear detrimental impacts that could have been at least partially mitigated in a healthier information environment”. The researchers promise us that “efforts to keep public discourse grounded in evidence will not only help to protect citizens from manipulation and the formation of false beliefs but also safeguard democracy more generally.”

NOS4A2

10.2kI recently read an article in Nature magazine in which researchers plead to their readers that we ought to care more about the threat of misinformation to democracy. To illustrate the threat they provide the typical examples, “false claims about climate change, the efficacy of proven public-health measures, and the ‘big lie’ about the 2020 US presidential election have all had clear detrimental impacts that could have been at least partially mitigated in a healthier information environment”. The researchers promise us that “efforts to keep public discourse grounded in evidence will not only help to protect citizens from manipulation and the formation of false beliefs but also safeguard democracy more generally.”

In their book The Misinformation Age, philosophers Caitlin O’Connor and James Weatherall come to the stunning conclusion that the same legislative prohibitions the state puts on false advertising, hate speech, and defamation ought to extend to misinformation. With existential threats like climate change and Donald Trump in our midst, websites such as Brietbart and Infowars are as dangerous to human health as the smoking lobby was before the regulation of cigarettes, so these propagandists need the sort of labelling that one might find on a pack of darts.

These two examples are meant to illustrate a perennial tale, that some individuals believe other individuals need to be protected from the kinds of information our betters do not approve of, and therefore monopoly on information needs to be achieved. In this case, our betters are advocating for some form or other of Official Truth and censorship so that others do not form “false beliefs”.

One wonders how it is that the authorities in this instance are immune to misinformation and false beliefs. Presumably some official will peruse misinformation just as anyone else, and therefor are at the very same risk of forming false beliefs as the rest of us, so it makes little sense to give some and not everyone the power to judge the veracity of information on their own accord. And given that falsity and false beliefs have been with us since the beginning, one wonders of its increasing criminalization as of late. Perhaps worse, our betters have never been that adept at disseminating the truth, historically producing its opposite on an industrial scale.

All of this leads me to conclude that the hubbub over misinformation is a campaign for more power rather than a legitimate plight for public safety. Their monopoly has and will continue to produce human rights abuses, all of which is a far greater threat to the public and to democracy than misinformation and false beliefs.

Their arguments are unconvincing. So I pose the question in the hopes that my fears may be satiated by someone smarter than me. Why should we worry about misinformation?

Nature - Misinformation poses a bigger threat to democracy than you might think

The Misinformation Age: How False Beliefs Spread

Poynter- A Guide to Anti-misinformation Actions Around the World. -

NOS4A2

10.2kAs a supplementary to the above, I’ll insert this quote from Karl Jaspers on censorship.

NOS4A2

10.2kAs a supplementary to the above, I’ll insert this quote from Karl Jaspers on censorship.

Now on censorship.

The public sphere forbids it. Only when it violates criminal code, like with slander and so on, there should be penalties.

But freedom of the press faces the objection that:

It does not promote enlightenment, but confusion.

It gives free reign to incitement against the government and the existing order.

It fosters discontent and mistrust.

It permits mockery of belief and authority

It not only gives the opportunity for truth but concerted lies and deceit.

Common interests that do not want knowledge, for example, produce public deception.

Therefor it is concluded that censorship is good and necessary.

People have to be protected from pernicious, corrupting influences, and truth withheld for one’s own good.

The answer:

Such arguments presuppose an immature people, whereas the desire for press freedom presupposes a people capable of maturity. In no way are we all mature; none of us are entirely mature; we’re all on the road to maturity.

But at every level, individuals, whether farmers or general laborers, general managers, chauffeurs, or professors, are more or less politically wise. This isn’t due to the level, but individual. We’re all human beings, and to repeat, we’re only ever on the road to maturity. It’s always human beings who censor what others are allowed to say publicly.

Censorship doesn’t make anything better. Both censorship and freedom will be abused. The question is simply: which abuse is preferable? Where’s the greater prospect? Censorship leads to both the suppression of truth and its distortion, while freedom only leads to its distortion. Suppression is absolute , but distortion can be straightened out by freedom itself.

The greater prospect is that, within and through the turbulence of opinions, truth can still crystallize in man by virtue of his innate sense of truth and the self-correction of critical publicity. Every other road leads to the downfall of truth for sure. The exclusive road is indeed no guarantee of success, but there’s hope.

Both freedom of the press and censorship put truth in danger, but again, which is the greater prospect? Which is the more honorable, appropriate for man? Only the path of freedom. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

Many harmful human rights abuses have been committed on such a premise.

Do you personally need someone to decide for you what you can and cannot read, what you should and shouldn’t believe, and so on, especially when such entities have been the greatest historical purveyors of misinformation? -

T_Clark

16.1kI recently read an article in Nature magazine in which researchers plead to their readers that we ought to care more about the threat of misinformation to democracy. To illustrate the threat they provide the typical examples, “false claims about climate change, the efficacy of proven public-health measures, and the ‘big lie’ about the 2020 US presidential election have all had clear detrimental impacts that could have been at least partially mitigated in a healthier information environment”. The researchers promise us that “efforts to keep public discourse grounded in evidence will not only help to protect citizens from manipulation and the formation of false beliefs but also safeguard democracy more generally.” — NOS4A2

T_Clark

16.1kI recently read an article in Nature magazine in which researchers plead to their readers that we ought to care more about the threat of misinformation to democracy. To illustrate the threat they provide the typical examples, “false claims about climate change, the efficacy of proven public-health measures, and the ‘big lie’ about the 2020 US presidential election have all had clear detrimental impacts that could have been at least partially mitigated in a healthier information environment”. The researchers promise us that “efforts to keep public discourse grounded in evidence will not only help to protect citizens from manipulation and the formation of false beliefs but also safeguard democracy more generally.” — NOS4A2

Whenever this subject comes up, someone points out that freedom of speech, the First Amendment here in the US, only applies to government action. It doesn't limit what individuals, corporations, or institutions can do about your or my speech. It's not against the law to fire someone or ask them to leave your house if you don't like what they say. Certain kinds of speech, e.g. slander and libel, can also be addressed under civil law. If I sue you for something you said, that's not a violation of free speech as it is usually understood. Here in the US, slander and libel are not crimes.

So... I don't see anything wrong with what the authors of the article wrote, at least as you've described it.

In their book The Misinformation Age, philosophers Caitlin O’Connor and James Weatherall come to the stunning conclusion that the same legislative prohibitions the state puts on false advertising, hate speech, and defamation ought to extend to misinformation. — NOS4A2

In the US, there are no "legislative prohibitions" against defamation and so-called hate speech. I'm not familiar with the laws regarding false advertising. I assume it is considered a type of fraud. As far as I know, it is still addressed in civil rather than criminal proceedings.

These two examples are meant to illustrate a perennial tale, that some individuals believe other individuals need to be protected from the kinds of information our betters do not approve of, and therefore monopoly on information needs to be achieved. In this case, our betters are advocating for some form or other of Official Truth and censorship so that others do not form “false beliefs”. — NOS4A2

Actions, including speech, have consequences. If those consequences harm someone, it may be appropriate for the harmed party to take the speaker to court. Do you have a problem with that?

One wonders how it is that the authorities in this instance are immune to misinformation and false beliefs. — NOS4A2

Do you have specific examples in mind of "authorities" putting the kibosh on someone's politically incorrect speech? If not, what's your kvetch? How about that - "kibosh" and "kvetch" in the same response.

All of this leads me to conclude that the hubbub over misinformation is a campaign for more power rather than a legitimate plight for public safety. — NOS4A2

Well, you certainly haven't made any case for your claim. Besides that, I'm with Mikie.

Oh cool, the dude who worships the guy who said anyone burning the flag should get put in jail is gonna lecture us on free speech absolutism. Pass. — Mikie

It's hard to take this seriously. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

Whenever this subject comes up, someone points out that freedom of speech, the First Amendment here in the US, only applies to government action. It doesn't limit what individuals, corporations, or institutions can do about your or my speech. It's not against the law to fire someone or ask them to leave your house if you don't like what they say. Certain kinds of speech, e.g. slander and libel, can also be addressed under civil law. If I sue you for something you said, that's not a violation of free speech as it is usually manifested. Here in the US, slander and libel are not crimes.

So... I don't see anything wrong with what the authors of the article wrote, at least as you've described it.

Freedom of speech is not the same as the first amendment, I'm afraid, so its a mistake to equate the two. That's fine, it's a common error.

I've described what's wrong with the argument further along in the post.

In the US, there are no "legislative prohibitions" against defamation and so-called hate speech. I'm not familiar with the laws regarding false advertising. I assume it is considered a type of fraud. As far as I know, it is still addressed in civil rather than criminal proceedings.

The US isn't the only country in the world. At any rate, this isn't about the United States and its legal system.

Actions, including speech, have consequences. If those consequences harm someone, it may be appropriate for the harmed party to take the speaker to court. Do you have a problem with that?

I do have a problem with that. The consequences of speech, for instance, is air and sound coming out of the mouth. To be fair, I'm willing to subject myself to a test if you wish to promote your harm theory. Let's see which injuries you can inflict on me with your speech.

Do you have specific examples in mind of "authorities" putting the kibosh on someone's politically incorrect speech? If not, what's your kvetch? How about that - "kibosh" and "kvetch" in the same response.

I put a link in the original post. It's old, so it may be out of date, but it shows how people and journalists around the world are being placed in jail on the premisses you advocate. I'll place the link below.

Poynter- A Guide to Anti-misinformation Actions Around the World. -

Leontiskos

5.6k

Leontiskos

5.6k

The problem is that "misinformation" and "disinformation" are nonsense terms. What are they supposed to mean?

Do not trust anyone who uses the words "disinformation" or "misinformation."

What they mean is "opinions that run contrary to mine that I should be allowed to suppress." — Jordan Peterson

Lots of folks around here can't handle Peterson, but he's right. Such words are bogeyman stand-ins meant to justify censorship. If someone disagrees then they will have to give their definition. The only plausible definition of such terms is either 'falsehood', or 'intentional (or intentionally harmful) falsehood'. Neither one is going to stand up in this debate, which is nothing more than a debate on free speech. What is at stake here is not truth but power. Truth is a sideshow, and it has been for some time:

So, by the middle of the 20th century, the scientific community — in the United States and many other Western countries — had achieved a goal long wished for by many of its most vocal members: it had been woven into the fabric of ordinary social, economic, and political life. For many academic students of science — historians, sociologists, and, above all, philosophers — that part of science which was not an academic affair remained scarcely visible, but the reality was that most of science was now conducted within government and business, and much of the public approval of science was based on a sense of its external utilities — if indeed power and profit should be seen as goals external to scientific work. Moreover, insofar as academia can still be viewed as the natural home of science, universities, too, began to rebrand themselves as normal sorts of civic institutions. For at least half a century, universities have made it clear that they should not be thought of as Ivory Towers; they were not disengaged from civic concerns but actively engaged in furthering those concerns. They have come to speak less and less about Truth and more and more about Growing the Economy and increasing their graduates’ earning power. The audit culture imposed neoliberal market standards on the evaluation of academic inquiry, offering an additional sign that science properly belonged in the market, driven by market concerns and evaluated by market criteria. The entanglement of science with business and statecraft historically tracked the disentanglement of science from the institutions of religion. That, too, was celebrated by scientific spokespersons as a great victory, but the difference here was that science and religion in past centuries were both in the Truth Business.

When science becomes so extensively bonded with power and profit, its conditions of credibility look more and more like those of the institutions in which it has been enfolded. Its problems are their problems. Business is not in the business of Truth; it is in the business of business. So why should we expect the science embedded within business to have a straightforward entitlement to the notion of Truth? The same question applies to the science embedded in the State’s exercise of power. Knowledge speaks through institutions; it is embedded in the everyday practices of social life; and if the institutions and the everyday practices are in trouble, so too is their knowledge. Given the relationship between the order of knowledge and the order of society, it’s no surprise that the other Big Thing now widely said to be in Crisis is liberal democracy. The Hobbesian Cui bono? question (Who benefits?) is generally thought pertinent to statecraft and commerce, so why shouldn’t there be dispute over scientific deliverances emerging, and thought to emerge, from government, business, and institutions advertising their relationship to them? — Harvard historian of science Steve Shapin, Is There a Crisis of Truth? -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

I agree. "Misinformation", by definition, is tantamount to falsity. But in practical use it is used to counter information those in power do not like. Any argument from any Western philosopher, like JS Mill or Bertrand Russel should suffice to refute such nonsense, but here we are. -

T_Clark

16.1kFreedom of speech is not the same as the first amendment, I'm afraid, so its a mistake to equate the two. That's fine, it's a common error. — NOS4A2

T_Clark

16.1kFreedom of speech is not the same as the first amendment, I'm afraid, so its a mistake to equate the two. That's fine, it's a common error. — NOS4A2

It's not a mistake and your response is disingenuous. There is no freedom of speech beyond what protections government or other institutions provide. Are you suggesting there should be? Are you suggesting people shouldn't be held accountable for what they say? Are you suggesting there should be no consequences for libel or slander? Are you suggesting the government should get involved in protecting freedom of speech beyond what they already do? What exactly are you suggesting?

The US isn't the only country in the world. At any rate, this isn't about the United States and its legal system. — NOS4A2

In your first paragraph you identify Trump's lies about the 2020 election as an example of the issue at hand. Caitlin O’Connor and James Weatherall are both American academics working in an American university. For you to say you're not talking about the US goes beyond disingenuity into intentional misleading.

I do have a problem with that. The consequences of speech, for instance, is air and sound coming out of the mouth. To be fair, I'm willing to subject myself to a test if you wish to promote your harm theory. Let's see which injuries you can inflict on me with your speech. — NOS4A2

As I asked before, are you suggesting that people shouldn't be accountable for what they say? That I shouldn't be able to sue you if you lie about me in a way that causes me harm? If that's what you mean, you should be clearer. It would involve a radical rewriting of civil law in the US and every other country in the world. Is that what you think is needed?

I put a link in the original post. It's old, so it may be out of date, but it shows how people and journalists around the world are being placed in jail on the premisses you advocate. — NOS4A2

Another false statement. The article you linked to identifies no country in North and South America or western Europe except France and Italy that have potentially significant restrictions. Indications of people being put in jail are primarily located in authoritarian countries in Africa and Asia. Is that it? You're worried about press freedom in Burkina Faso?

You've just made up this whole issue so you can paint your preferred right-wing political cohort as unjustly persecuted. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

It's not a mistake and your response is disingenuous. There is no freedom of speech beyond what protections government or other institutions provide. Are you suggesting there should be? Are you suggesting people shouldn't be held accountable for what they say? Are you suggesting there should be no consequences for libel or slander? Are you suggesting the government should get involved in protecting freedom of speech beyond what they already do? What exactly are you suggesting?

It is a huge mistake to equate an amendment to a constitution with the principle or right it is meant to protect. It’s nothing short of circular. The first amendment doesn’t protect the first amendment.

All I have suggested is that there should be no law to suppress misinformation. I thought that was obvious, since I’ve said as much.

As I asked before, are you suggesting that people shouldn't be accountable for what they say? That I shouldn't be able to sue you if you lie about me in a way that causes me harm? If that's what you mean, you should be clearer. It would involve a radical rewriting of civil law in the US and every other country in the world. Is that what you think is needed?

They should be held accountable, and the best way to

do so is to counter their falsity with truth. The history of censorship and free speech attests that censorship is not the answer.

Another false statement. The article you linked to identifies no country in North and South America or western Europe except France and Italy that have potentially significant restrictions. Indications of people being put in jail are primarily located in authoritarian countries in Africa and Asia. Is that it? You're worried about press freedom in Burkina Faso?

You've just made up this whole issue so you can paint your preferred right-wing political cohort as unjustly persecuted.

It has Canada, Mexico, and Brazil in there. But see I don’t need to counter your misinformation with censorship. More information suffices. But yes, I worry that free speech is being stamped out worldwide. If you don’t, that’s fine.

Gavin Newsome just passed a law combatting deepfakes.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/17/technology/california-deepfakes-law-social-media-newsom.html -

jorndoe

4.2kShouting fire in a crowded theater (falsely)

jorndoe

4.2kShouting fire in a crowded theater (falsely)

Some typical responses at the edges:

If people panic and some are trampled to death, then the tramplers are at fault, not the inciter.

If the inciter aimed to cause panic, then they're at fault, possibly a sociopath.

You could argue either, right?

Presumably, legislation would follow ethics.

As usual, we have whatever examples, and a simple universal decision/rule is suspect. -

Igitur

75The answer to the question at the end of this OP is easy to answer.

Igitur

75The answer to the question at the end of this OP is easy to answer.

We should worry about misinformation because it’s effective and because usually misinformation means a darker truth is being hidden, one that it would be good for the public to know about.

However, that’s not what I think this is actually about. The argument you made is more relevant to the question: “How should we go about avoiding misinformation?” and I believe the best plausible solution is just to rely on individuals who care using their resources to find truth on their own.

Having someone else tell you what's true just adds another chance for the truth to get corrupted. -

Tarskian

658All of this leads me to conclude that the hubbub over misinformation is a campaign for more power rather than a legitimate plight for public safety. — NOS4A2

Tarskian

658All of this leads me to conclude that the hubbub over misinformation is a campaign for more power rather than a legitimate plight for public safety. — NOS4A2

It is actually possible to set up decentralized censorship-resistant information publication networks.

For example, Bitcoin is one. The powers-that-be cannot prevent the publication of money-moving transactions on the Bitcoin blockchain. It is beyond the capacity of any government on earth to do that.

Unfortunately, it would be prohibitively expensive to cover ordinary non-financial speech with electricity-based proof-of-work protection.

Conclusion. We would have censorship-resistant social media, if we agreed to pay for that. -

Tarskian

658The Nostr protocol claims to be censorship resistant:

Tarskian

658The Nostr protocol claims to be censorship resistant:

https://www.voltage.cloud/blog/nostr-the-decentralized-censorship-resistant-messaging-protocol

Nostr: The Decentralized, Censorship-Resistant Messaging Protocol

In a world where centralized entities increasingly control digital communication, the demand for more transparent, private, and censorship-resistant systems is growing. One of the technologies that promise to deliver this independence is Nostr, a decentralized messaging protocol.

The author claims that it is enough to "distribute data across a network of peers" in order to achieve censorship resistance:

What sets Nostr apart from other messaging services is its decentralized nature. Unlike centralized platforms—where data is stored and managed by a single organization, like a corporation or a government—Nostr doesn't rely on a single server or entity. Instead, it distributes data across a network of peers (nodes known as relays) that participate in storing and transmitting messages.

I have my doubts about that.

In that case, it would also be enough to just distribute money-moving transactions across a network of peers in order to implement something like Bitcoin. There would be no need to burn lots of electricity as proof of work.

I personally do not believe that the principle of "distribution" alone would be enough to fend off the censorship attacks of a determined state actor. In my opinion, it takes a lot more effort to put up a credible anti-Statist defense. Everything else is just an exercise in wishful thinking.

Anti-Statist measures are possible but they are invariably costly. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

Good points.

I note that many of the fears over misinformation mention the threat to some amorphous, ill-defined order. Both China and the EU have this in common. From the EU, “The risk of harm includes threats to democratic political processes, including integrity of elections, and to democratic values that shape public policies in a variety of sectors, such as health, science, finance and more.” Or for China it threatens to “undermine economic and social order”. It’s clear to me that it is a threat to the state. Therefor, digital authoritarianism and the control of information is required. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

That seems to me to be a stupid idea, not well thought out at all, because if lying is universal and comprehensive your authorities would be subject to lie. And that’s a common argument for free speech and against censorship that maybe someone who doesn’t understand it hasn’t pondered before: who decides and enforced what is true and what is false? Personally I can’t think of any people, alive or dead, fit for such a task.

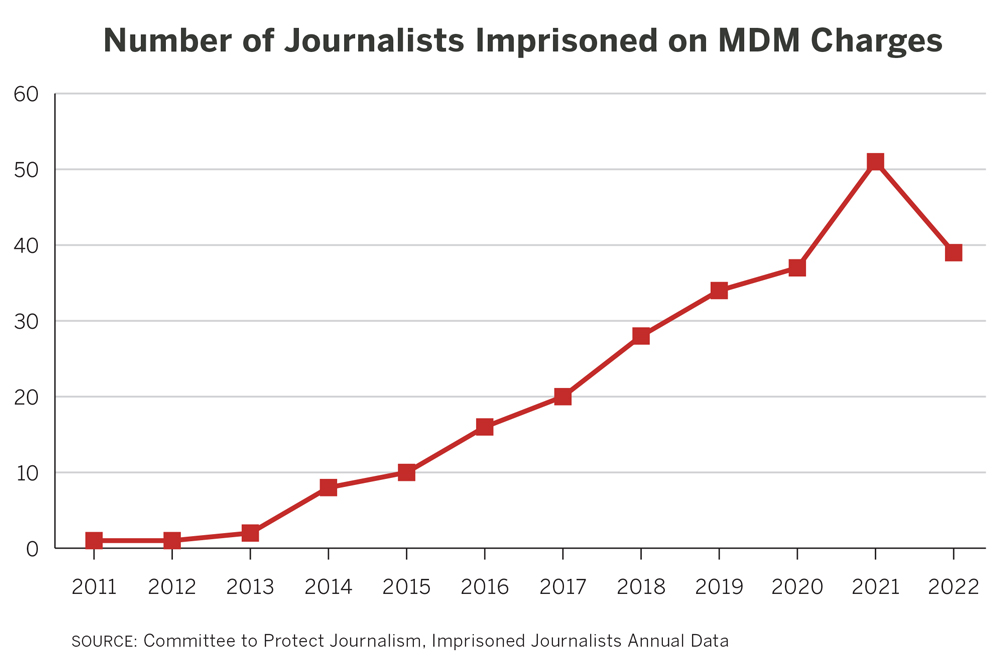

But you’d be happy to know that the jailing of journalists is on the increase since such measures have been adopted.

https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/chilling-legislation/ -

Philosophim

3.6kI think worrying about misinformation is obvious. Lies are intended to distort reality for a particular individual's gain. A distorted perception of reality means more mistakes, missteps, abuse, etc. People die. Covid misinformation caused the death of thousands of people for example.

Philosophim

3.6kI think worrying about misinformation is obvious. Lies are intended to distort reality for a particular individual's gain. A distorted perception of reality means more mistakes, missteps, abuse, etc. People die. Covid misinformation caused the death of thousands of people for example.

What you're really concerned with is, "Can government handle misinformation?" Of course. It already does today. Libel, slander, and outright intent to deceive for monetary gain are already handled fairly well under the law. There are a few keys that need to be in place if we were to expand the laws to other things such as "Misinformation to voters".

1. Innocent until proven guilty. This one I'm sure is obvious to you.

2. A high burden of proof. An individual must have clear evidence that they knowingly lied. It must be clear that the person did not imply that it was an opinion. "I think Ivermectin will help Covid" is different from, "Ivermectin has been proven to help Covid and is better than all the other medications out there."

3. A chance at remission. Sentencing or fees can be lowered or eliminated if the person in the wrong publicly comes out and admits guilt, and presents the evidence of what is actually true. The point is not to punish, the point is to ensure the public has access to the truth.

4. Harsh penalties on the campaign trail. This ensures it is more difficult for people who would deceive the American people to get elected.

Again, careful law crafting and jurisprudence can ensure misinformation is handled well without stepping on the first amendment. -

flannel jesus

2.9kOn the one hand, it's obvious that people making decisions based on lies and falsehoods is undesirable. I mean, if your eyes are telling you there's safe ground ahead, but that's not the truth and you're about to step off a roof, then ... you know, false information is obviously not great for making good decisions. So talking about it like misinformation isn't a problem *at all* seems silly to me. There's some very obvious problems with an information economy that's flooded with lies.

flannel jesus

2.9kOn the one hand, it's obvious that people making decisions based on lies and falsehoods is undesirable. I mean, if your eyes are telling you there's safe ground ahead, but that's not the truth and you're about to step off a roof, then ... you know, false information is obviously not great for making good decisions. So talking about it like misinformation isn't a problem *at all* seems silly to me. There's some very obvious problems with an information economy that's flooded with lies.

On the other hand, having a central government authority deciding which things are the orthodox truth is similarly dangerous. A lot of naive online leftists seem to believe that truth-determining organizations are a clearly good thing, but they only think that as long as the truth-determining organizations believe the things they believe - they don't think about what happens when *the other side* get control of the official truth. They're short sighted about that, many of them.

So I think misinformation should absolutely be fought, and is a real problem - but I have no idea how to fight it, and giving governments the power to choose truth seems kinda insane to me.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum