-

Janus

18kThe way I see it the world is always already interpreted, so we are not going to agree about this.

Janus

18kThe way I see it the world is always already interpreted, so we are not going to agree about this.

Our interpetations are constrained by the nature of the world including ourselves, so it's not right to say that we create the world. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThe way I see it the world is always already interpreted, so we are not going to agree about this. — Janus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThe way I see it the world is always already interpreted, so we are not going to agree about this. — Janus

How do you make that consistent with what you said earlier:

It is true that the way we perceive the world is conditioned by the ways in which our sentient bodies and brains are constituted. The suggestion that the mind creates the world, rather than merely interprets it seems absurd and wrong. — Janus

If, "already interpreted" is a prerequisite of there being such a thing as "the world", and minds do the job of interpreting, how would you dismiss the proposition that the mind also creates the world, being prior in time to the world? Since a mind is already necessarily prior to the world to perform that interpretation which is already done in order for there to be such a thing as the world, it seems very likely, rather than absurd, that a mind also creates the world.

Our interpetations are constrained by the nature of the world including ourselves, so it's not right to say that we create the world. — Janus

If the world is always already interpreted, then an interpretation is prior in time to the world. Why would you think that the interpretation which is prior in time to the existence of the world, would be constrained by the world? As is the case with cause and effect, the posterior is constrained by the prior, not vise versa. -

Janus

18kIf, "already interpreted" is a prerequisite of there being such a thing as "the world", and minds do the job of interpreting, how would you dismiss the proposition that the mind also creates the world, being prior in time to the world? — Metaphysician Undercover

Janus

18kIf, "already interpreted" is a prerequisite of there being such a thing as "the world", and minds do the job of interpreting, how would you dismiss the proposition that the mind also creates the world, being prior in time to the world? — Metaphysician Undercover

The bodymind interprets what is given to it precognitively. It doesn't create what is given, at least I find it most plausible to think that it doesn't. There are two senses of 'world' here. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k

You're missing the point. The act, which is called "interpretation", "to interpret", requires a relationship of representation of some sort. This is commonly understood as the relationship between sign and what is signified by the sign. It could also be understood as information and what the information says. To "interpret" is to bring out the meaning which is apprehended as being inherent within this relationship between sign and signified. So any act of "interpretation" requires these two aspects, with this relationship. For simplicity we could say these two are signs and what is signified, representation, and what is represented, or, the information and what the information says, or means.

So if the body/mind "interprets what is given to it", then what is given to it is the signs, information, or representation. But we still must consider the separation between the representation given to the body/mind and what is represented by that representation, or, the separation between the information given, and what the information says, signs and what is signified.

In the act of interpretation, "what is represented", or, "what the information says", is something created by the mind of the interpreter. The interpreter looks at the representation or information, and produces (creates) what is thought to be the meaning of it. "What is represented", "what the information says", "what is signified by the signs", is a creation of the interpreting mind.

Therefore, if "the bodymind interprets what is given to it precognitively", as you say, and what is given to it is a representation, sign, or information (as implied by the concept "interpret"), then what is represented by that information which is given to the mind precognitively, is something created by the mind in this act of interpretation. And so, if "what is given to it precognitively" is determined to be a representation of "the world", or information about "the world", then the world as what is determined as being represented, through the act of interpretation, is something created by the mind which interprets the representation, signs, or information. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe easiest way to frame it is that self and world are co-arising. That is a perspective shared by both the embodied cognition school and Buddhism. It eliminates the constant vacillation between objective and subjective. There is no absolute object (materialism) or absolute subject (subjective idealism).

Wayfarer

26.2kThe easiest way to frame it is that self and world are co-arising. That is a perspective shared by both the embodied cognition school and Buddhism. It eliminates the constant vacillation between objective and subjective. There is no absolute object (materialism) or absolute subject (subjective idealism). -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

The "blind faith" was snuck into the book only in the final chapter, after many chapters of "rational argumentation" against commonsense Materialism, and even Kingsley's version of Idealism. So, how am I to interpret "transcending reason through reason" except as a "rational" choice to close the eyes to "objective" Reality, and take a leap of faith into extrasensory subjective Ideality*1? :smile:None of which has much to do with blind faith, has it? — Wayfarer

*1. Eyes of Faith, not Reason :

He has said "He who has eyes to see, let him see, and he who has ears to hear, let him hear." This whole concept of the Lord coming to make someone blind or giving sight to those who cannot see is hard to visualize (no pun intended).

https://www.dneoca.org/articles/eyestosee0794.html

I'm aware that Kastrup's language could be "misinterpreted" by those who are alien to egoless Eastern maya-based*2 worldviews. But my own personal experience, with mostly Western religions, taught me to be on-guard against those who use Maya/illusion concepts to undermine confidence in my personal reasoning abilities. Christianity uses the image of deceiving Satan for the same effect : to make believers dependent on "seers" & "prophets" for their knowledge of paradoxical Truth. So, my problem is not prejudice against Kastrup's idiosyncratic Idealism, but of the necessity for making his esoteric ideas fit into my own personally experienced model of reality, that has outgrown some Western religious beliefs, by means of philosophical reasoning. Even as I try to keep an open mind to unfamilar ideas, I remain unable to access those hearsay "foundational beliefs . . . . underlying everything". :cool:Quote from Science Ideated : "The point here, however, isn’t that reality is constituted by personal, egoic beliefs; the foundational beliefs in question aren’t accessible through introspection; they underly not only a person, not only a species, not only all living beings, but everything. They aren’t our beliefs, but the beliefs that bring us into being in the first place". — Wayfarer

*2.What does Maya mean spiritually?

Maya originally denoted the magic power with which a god can make human beings believe in what turns out to be an illusion. By extension, it later came to mean the powerful force that creates the cosmic illusion that the phenomenal world is real.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/maya-Indian-philosophy

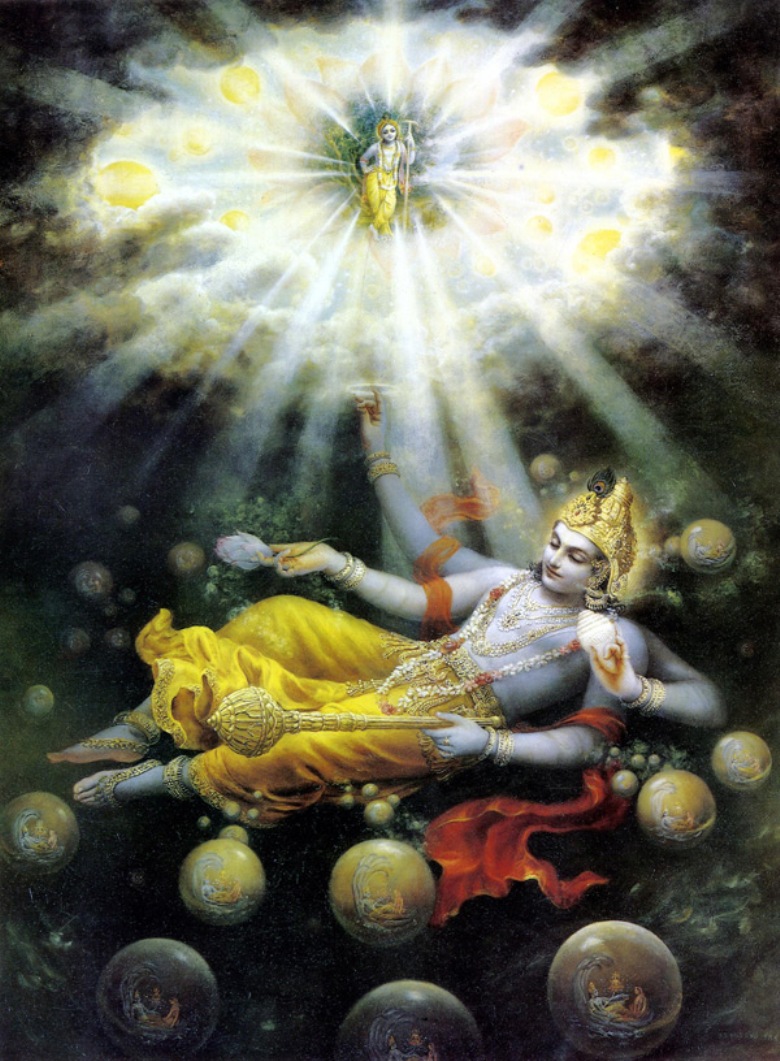

Yes. I am aware that my "ego's role" in construing the world is an obstacle to the Buddhist goal of "non self" (i.e. perfect objectivity or God's view of the world). I suppose, if "god" wanted us mortals to "become like God" (Genesis 3:5), then s/he wouldn't allow Satan/serpent/Maya to deceive us with the apple of Egoism. Does it make sense to sacrifice the Self (soul) in service to an anonymous/imaginary Cosmic Concept? To me --- in view of recorded human history of religious warfare*3 --- it seems like a choice between self-control and other-control. {image below} :gasp:'egological'. . . . . Rather it pertains to the way the ego constitutes experience of the objective world into a coherent, subjective stream of consciousness related to the ego or self — Wayfarer

*3. Divine Dharma & Karma Yoga :

To set the stage, the Bhagavad Gita begins with Arjuna and his family about to go to war with one another. Not wanting to shed his families' blood, Arjuna refuses to fight. Ironically, this is where the god Krishna steps in and tries to convince Arjuna it is his duty to kill his rebellious kinsmen.

https://study.com/academy/lesson/the-bhagavad-gitas-story-of-arjuna-krishna-the-three-paths-to-salvation.html

"Everyday standpoint = common sense?? If so, I suppose I am one of those "foolish ordinary people" who put their trust in personal reasoning, in order to defend against exhortations to take some sacred ideas on ego-blinded faith*4. Most doctrinal religions encourage their "ordinary people" to submerge their egos into a faith community, a single-minded union of believers : "being in full accord and of one mind" (Philippians 2:2). I'm OK with unbiased-universal-perspective as a philosophical concept, but not OK with religious exhortation to extinguish the ego. I'm wary of becoming a remote-controlled robot, subject to centralized orders from high command {image below]. Do Islamic terrorists submerge their egos, and sacrifice their bodies, in order to serve their omnipresent-but-invisible Allah? :chin:it encourages us to go beyond the egological constitution of internal and external objects which `foolish, ordinary people’ habitually `seize’ upon in their everyday standpoint. — Wayfarer

*4. Eye of Faith reveals unseeable Allah :

"Well, HE is invisible for those who do not believe in HIS existence."

https://www.quora.com/Is-it-true-that-Allah-is-invisible-If-yes-then-why-did-he-ask-the-polytheists-to-show-their-Gods-knowing-that-Gods-are-invisible-How-can-non-Muslims-subscribe-to-Islam-when-its-God-say-such-meaningless-things-Or-is

My hybrid matter/mind-based philosophical worldview accepts the subjectivity of its own "reality" model. But my BothAnd bridge-between-worldviews allows me to imagine that hypothetical divine objective perspective, even as --- in the absence of divine revelation --- I make-do with my innate subjective view of the outside world. I can accept the natural world of the senses as the "inherent reality", while labeling the metaphysical model of that world as an as-if ivory-tower artificial reality : i.e. Ideality. One "reality" has physical Properties (possessions), while the other has metaphysical Qualities (attributes). Like Infinity, we can aspire to perfect Objectivity, but our attempts, on an asymptotic curve, miss the ultimate goal :nerd:transcend the mentality which invests the objective domain with an inherent reality which it doesn't possess — Wayfarer

How would you fairly assess the ego-less faith of Islamic terrorists (as one example among many of faith-motivated extremists)? Would it be more appropriate for me to "engage" with a Christian Mysticism that is closer to my own background? The peaceful Quakers (or Islamic Sufis), for example. They "believe that all people are capable of directly experiencing the divine nature of the universe". But they don't seem to be violent or robotic to me. Perhaps because their individualized experiences of divinity are not easily translated into centralized directives. "Spirit led" is a nice theory, but dogmaless Ego interpretations tend to keep them quiescent, instead of aggressive, in practice. Their unorthodox religions were persecuted in the early years, but their institutional passivity eventually allowed them to co-exist with non-mystical Christians, who had more threatening fish to fry. Do these egoless exceptions to the ego-driven rule fit into your Mind-Created World picture? Would I be advised to join them in their direct access to Divine Mind? :chin:"egoless mechanical robot/slaves" would indeed be an unfair assessment. Would it be wise for you to engage with Sufism? Probably not, given your background. — Wayfarer

Again, you imply implacable prejudice against doctrinal religion due to its restraints on ego-serving Reason. It's true that my religious upbringing involved minimal mystical elements, but it also had no official creed, so each believer was expected to interpret difficulties in the received scriptures according to his own "reasoning". Like the Quakers, it had few doctrinal rules, apart from the admittedly ambiguous New Testament record of early Christian beliefs. Hence, we didn't have any creedal or papal justification for burning infidels at the stake.The fact that you can only interpret any of this as 'religious dogma' seems to me, and pardon me for saying, a consequence of the views you bring to it. — Wayfarer

In retrospect, it seemed almost like non-dogmatic Buddhism*5, due to its "rational, individualistic, and democratic “spirituality”. So, my individualistic interpretations ("views") of Christian traditions were tolerated, as long as I didn't make an issue of it. My label of "religious dogma" was intended only in the sense that most sects have a few basic rules (doctrines) that establish their position in the plethora of religious interpretations "views" of their belief community. I have no animus against practical rules (doctrines) for governing religious communities. I do, however, have a skeptical philosophical attitude toward unquestioning Blind Faith as a condition of membership. :smile:

*5. Buddhist Doctrine (dogma) :

Buddhists believe that the human life is one of suffering, and that meditation, spiritual and physical labor, and good behavior are the ways to achieve enlightenment, or nirvana.

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/buddhism/

Note --- Compare Zen Calvinism

EGOLESS CENTRALLY-CONTROLLED ROBOT ARMY OF GOD

-

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

The Gnomon quote is how I understand the phrase "a mind-created world". But the Wayfarer quote seems to imply that my individual ego-driven Soul/Self/Mind does create, not a separate simplistic subjective model-world, but the actual all-inclusive complex objective world of physical bodies and metaphysical minds, from the whole cloth of unlimited imagination. That would be a good trick for a god {image below}, but could a very limited mind like mine pull it off? The duality is a distinction between one man's imagination, and the one real world of space-time, or perhaps a Cosmic Mind's Maya illusion.Not to create a physical world from scratch, but to create a metaphysical model of the world that we sense (feel) and make-sense of (comprehend). ___Gnomon

Notice the duality you introduce between model and world — Wayfarer

Kant's Transcendental Idealism*1 seems to imply an unbridgeable (dualistic) gulf between imperfect & incomplete (i.e. evolving) physical Reality, and a perfect & unchanging metaphysical Platonic Ideality. The human ego produces an imaginary (ideal) world model, limited in scope & detail by our inborn or learned assumptions and associations*2. At least, that's how I interpret his notion of a transcendent ideal world*1. Other than divine magic, does your concept of a Mind-Created World agree with Kant, or a more radical sense of "created"? :smile:

PS___The NETFLIX movie Freud's Last Session, provides a fictional encounter between Sigmund Freud, a famous atheist, and C.S. Lewis, a former atheist who converted to a personal (non-Catholic) faith in "Mere Christianity"*3. Their gentlemanly give & take discussion reminded me of our dialogues, even though I am not an angry Atheist, and you are not a non-denominational Christian.

*1. Kant's Mind-Created World :

Kant's transcendental conditions of knowledge portray the mind not as creating the physical world, but as necessarily structuring our knowledge of objects with a set of unconscious assumptions; yet our pre-conscious (pre-mental) encounter with an assumed spatio-temporal, causal nexus is entirely physical.

https://philarchive.org/archive/PALKPS-4

Note --- Are those "unconscious assumptions" the prejudices you see in my dualistic worldview?

The "causal nexus" may be another term for my own EnFormAction hypothesis.

*2. Kant’s Perspectival Solution to the Mind-Body Problem :

Kant’s Critical philosophy solves Descartes’ mind-body problem, replacing the dual-

ism of the “physical influx” theory he defended in his early career. Kant’s solution, like

all Critical theories, is “perspectival,” acknowledging deep truth in both opposing

extremes. Minds are not separate from bodies, but a manifestation of them, each

viewed from a different perspective. Kant’s transcendental conditions of knowledge

portray the mind not as creating the physical world, but as necessarily structuring our

knowledge of objects with a set of unconscious assumptions; yet our pre-conscious

(pre-mental) encounter with an assumed spatio-temporal, causal nexus is entirely

physical. Hence, today’s “eliminative materialism” and “folk psychology” are both

ways of considering this age-old issue, neither being an exclusive explanation. A

Kantian solution to this version of the mind-body problem is: eliminative materialism

is good science; but only folk psychologists can consistently be eliminative material-

ists. Indeed, the mind-body problem exemplifies a feature of all cultural situations:

dialogue between opposing perspectives is required for understanding as such

to arise.

https://philarchive.org/archive/PALKPS-4

Note --- The "perspectival" solution to opposing worldviews may be similar to my own BothAnd methodology.

*3. The Most Reluctant Convert :

His faith changed his direction from “self-scrutiny” to “self-forgetfulness.”

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/resources/the-most-reluctant-convert/

Note --- Could "self-forgetfulness" be a form of non-self egolessness?

Vishnu Dreaming Worlds into Existence

-

Wayfarer

26.2kdoes your concept of a Mind-Created World agree with Kant, or a more radical sense of "created"? — Gnomon

Wayfarer

26.2kdoes your concept of a Mind-Created World agree with Kant, or a more radical sense of "created"? — Gnomon

The first footnote in the Medium version of the essay refers to Kant, as does the first quotation from the Charles Pinter book Mind and the Cosmic Order, which I understand you're familiar with. I would hope overall not to stray too far out of the bounds set by Kant.

Of course it is true that Kant is extremely difficult to read and comprehend and I don't claim to have a comprehensive understanding of his writings, only of some of the salient points of the CPR. I first encountered him through a book called The Central Philosophy of Buddhism by T R V Murti. Murti was a mid-twentieth century Indian scholar - he had very much a kind of cosmopolitan Oxford outlook. This book is nowadays criticized for its perceived eurocentrism and tendentiousness. However when I did my MA in Buddhist Studies ten years ago, my thesis supervisor endorsed it. It was central to my spiritual formation, such as it is. (An example can be found here.)

The book comprises an analysis of the Madhyamaka (Middle Way) philosophy of Nāgārjuna who is a principle figure in the development of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Throughout the book Murti compares Madhyamaka with Kant, Hegel, F H Bradley and David Hume, as well as other forms of Indian philosophy, specifically Advaita. Murti claims that Nāgārjuna's dialectic, the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (MMK) is 'the central philosophy of Buddhism' centered around the Buddhist principle of śūnyatā. This is misleadingly often presented as 'nothingness' and the MMK as nihilistic, both by friends and foes of the religion, although it is not actually that. It arises, he says, from the inexorable conflicts within reason itself - hence the comparisons with Kant, in particular, a detailed comparison of Kant's antinomies of reason, and Buddha's 'unanswerable questions' (avyākṛta). The origins of the madhyamaka can be traced back to those passages in the early Buddhist texts where the Buddha declines to answer whether there is a self or not, and other such questions, both affirmation and negation being incorrect responses (and the Buddha's lack of response being customarily described as a 'noble silence', see for example Ananda Sutta).

Like phenomenology, Buddhism is grounded very much in 'observation of what is' - paying very close attention to the nature of experience (which is really what 'mindfulness' means, aside from its pop-cultural references). It discourages metaphysical speculation, although that ought not to be interpreted as a kind of early naturalism or positivism. It is a religion although it is based on a completely different belief system to the Biblical religions. But because it's a religion, we generally fall back on the cultural religious tropes we've become accustomed to in order to understand it (and I'm aware of that tendency in myself.) But I'm trying to stay within the bounds of philosophical discourse in all of the above. -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

I've never attempted to read Kant's "difficult" works, so I only know the Wikipedia version. But I have read Pinter's Mind and the Cosmic Order. Both of those explanations of the Mind/World relationship are easier for me to identify-with than the Hindu/Buddhist texts. In my blog book review*1, I found Pinter's western-oriented analysis of the Real vs Ideal question to be mostly compatible with my own.The first footnote in the Medium version of the essay refers to Kant, as does the first quotation from the Charles Pinter book Mind and the Cosmic Order, which I understand you're familiar with. I would hope overall not to stray too far out of the bounds set by Kant. — Wayfarer

For example, in order to make sense of the Buddha's "śūnyatā", I would have to picture its "emptiness" in terms of the void or nothingness (absence of matter) that presumably preceded the Big Bang of modern Western cosmology. In my own worldview, I imagine the logically necessary First Cause as existing eternally in an un-real im-material meta-physical state of Nothingness, that we westerners call "Potential". Perhaps, when my Ego is "extinguished" in death/nirvana, my self/soul will return to the void/sunya from whence it came. It's just speculation, but, for a Materialist, even that secularized de-personalized implication of matterless existence might be as unrealistic as any religious heaven.

The Nothing vs Something notion of Shunyata is itself a dualism. But then, the only way to eliminate Dualism in philosophy is to avoid rational analysis of whole systems into more digestible parts : e.g. Mūlamadhyamakakārikā vs 'Root Verses on the Middle Way'. For most of us, the first step toward understanding is to differentiate This-from-That, or Real-from-Ideal. Besides, without analytical Reason, we would have nothing to talk about, and this forum would have to communicate directly and wordlessly via mind-reading. :smile:

*1. Creative Mind and Cosmic Order :

The traditional opposing philosophical positions on the Mind vs Matter controversy are Idealism & Realism. But Pinter offers a sort of middle position that is similar in some ways to my own worldview of Enformationism.

http://bothandblog8.enformationism.info/page10.html -

Wayfarer

26.2kFor example, in order to make sense of the Buddha's "śūnyatā", I would have to picture its "emptiness" in terms of the void or nothingness (absence of matter) that presumably preceded the Big Bang of modern Western cosmology. — Gnomon

Wayfarer

26.2kFor example, in order to make sense of the Buddha's "śūnyatā", I would have to picture its "emptiness" in terms of the void or nothingness (absence of matter) that presumably preceded the Big Bang of modern Western cosmology. — Gnomon

That is how it is nearly always (mis)interpreted. Your interpreting it as 'nothing as opposed to something', or the 'cosmic void'. It's not that, but don't feel as though you're alone in seeing it that way, it is an almost universal misunderstanding.

But for an introduction to its meaning in practice see this short article, What Is Emptiness?:

Emptiness is a mode of perception, a way of looking at experience. It adds nothing to and takes nothing away from the raw data of physical and mental events. You look at events in the mind and the senses with no thought of whether there’s anything lying behind them. — Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Please note, and without any pejorative intent on my part, the contrast with your imaginings of what might happen in the event of death, or what existed before the singularity. It's not found in imaginings or projections (hence the discouragement of speculative metaphysics!)

My take on 'emptiness' is that it is the seeing through of automatic projections - thought-patterns - associated with objects, situations and experiences. These manifest as identification- this is me! I am that! This is mine! together with the associated feelings of pride and shame, gain and loss, and so on. Obvious examples would be pride of ownership, status, the esteem of others, and the like. Recall Buddhism was a renunciate religion, and though we obviously aren't and probably won't ever be actual renunciates, that helps to understand the rationale and background.

'Emptiness' is 'realising what is' once all of those associations and attachments are in abeyance and they no longer hold sway over the passions. Notice the resemblance to Stoicism and other schools of pre-modern philosophy. The habitual tendencies and projections we have are saṃskāra, 'thought-formations': 'a complex concept, with no single-word English translation, that fuses "object and subject" as interdependent parts of each human's consciousness and epistemological process. It connotes "impression, disposition, conditioning, forming, perfecting in one's mind, influencing one's sensory and conceptual faculty" as well as any "preparation, sacrament" that "impresses, disposes, influences or conditions" how one thinks, conceives or feels.' (Wiki)

:up: Good review of Pinter's book. Again, I hope nothing here is incompatible with that. -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

Apparently, the Buddha's "emptiness" is supposed to be taken metaphorically instead of literally. The Bhikkhu quote describes it as a "mode of perception", which I would interpret as an attitude of "open-mindedness". And which, as described in the link below, should be essential for the practice of philosophy. But religious Faith would seem to be the antithesis : to hold stubbornly to "one's favored beliefs". Long ago, I gave-up my childhood faith, and have not found any ready-made off the shelf belief system to replace it.That is how it is nearly always (mis)interpreted. Your interpreting it as 'nothing as opposed to something', or the 'cosmic void'. It's not that, but don't feel as though you're alone in seeing it that way, it is an almost universal misunderstanding. — Wayfarer

That's why, over many years, I have been reviewing a variety of alternative religious, scientific, & philosophical beliefs, as I gradually construct a customized bespoke physical/metaphysical worldview of my own. I try to keep an open mind*1, but retain the truth-filter of skepticism*2 to weed-out any true-believer BS. Since I have never experienced anything Mystical or Magical, I am not predisposed to accept paranormal or transcendental beliefs that require a prejudicial "eye of faith".

The C.S. Lewis quote in my post above noted that "His faith changed his direction from 'self-scrutiny' {introspection?} to 'self-forgetfulness' {dissociation?}". {my brackets} Hence, as an adult he was transformed from dour Irish Anglican upbringing, to death-dispirited Atheist, to liberal non-denominational Theist. Does that sound like a case of "emptiness" or "open-mindedness" or "no self" to you? Obviously, he created a new personal worldview, but did his mind create a new world, in the sense of the OP? :smile:

*1. Open-mindedness is the willingness to search actively for evidence against one's favored beliefs, plans, or goals, and to weigh such evidence fairly when it is available.

https://www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu/newsletters/authentichappinesscoaching/open-mindedness

*2. Skepticism is derived from the word skepsis, which means inquiry, examination, or investigation of a perception. More specifically, scientific skepticism refers to a method of systematic doubt used to objectively examine a premise, usually on the basis of empirical evidence, wherever possible. It is about cultivating critical habits of mind to weigh evidence. Scientific skepticism is a balance between being open to new ideas and being skeptical of claims that lack supporting evidence.

https://www.intelligentspeculation.com/blog/skepticism-not-cynicism-for-a-world-dependent-on-intellectual-inquirynbsp

Emptiness, the most misunderstood word in Buddhism?

The first meaning of emptiness is called "emptiness of essence," which means that phenomena [that we experience] have no inherent nature by themselves." The second is called "emptiness in the context of Buddha Nature," which sees emptiness as endowed with qualities of awakened mind like wisdom, bliss, compassion,

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/emptiness-most-misunderstood-word-in-buddhism_b_2769189 -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe Bhikkhu quote describes it as a "mode of perception", which I would interpret as an attitude of "open-mindedness". — Gnomon

Wayfarer

26.2kThe Bhikkhu quote describes it as a "mode of perception", which I would interpret as an attitude of "open-mindedness". — Gnomon

Not exactly. It's more concerned with paying close attention to the nature of experience. As I said above:

My take on 'emptiness' is that it is the seeing through of automatic projections - thought-patterns - associated with objects, situations and experiences. These manifest as identification- this is me! I am that! This is mine! together with the associated feelings of pride and shame, gain and loss, and so on. — Wayfarer

That is not really 'open-mindedness' in an 'anything goes' sense.

As far as scepticism is concerned, there's a proposed link between a school of ancient Greek scepticism founded by Pyrrho of Elis and Buddhist philosophy. The theory is that Pyrrho travelled to Bactrian India (likely the Swat Valley straddling Afghanistan and Pakistan) which was then a Buddhist cultural center, and sat with the Buddhists. From this, he got his 'suspension of judgement', which resembles the Buddhist 'nirodha', or 'cessation'. That is the origin of scepticism, but it's nothing like today's armchair scepticism, which challenges claims to any kind of knowledge. Again it's more concerned with awareness of the disturbing patterns of thought and emotion rather than establishing a dogmatic truth claim. (Rather an interesting blog post on that can be read here.)

Obviously, [C S Lewis] created a new personal worldview, but did his mind create a new world, in the sense of the OP? — Gnomon

Need to be careful about what the meaning of 'creating' is in this context. An observation I have read is that the etymology of 'world' is an old Dutch term 'werold' meaning 'time of man' (ref), meaning that the connection with humanity is intrinsic to it. Whereas it is natural nowadays, with our modern awareness of the vastness of time and space, to see ourselves as transitory phenomena, 'mere blips' as the saying has it. But what the OP is pointing out, is that the vastness of time and space is unintelligible in the absence of perspective, and perspective can only be brought to bear by an observer. That's the central conflict I'm pointing out. (It's also a realisation that has dawned on physicists.)

//

There's another difficult point I want to make. The above connection between Buddhism and scepticism seems counter-intuitive - Buddhism is a religion, so how can be it also sceptical? This apparent conflict stems from a largely Western interpretation of what religion entails. In the West, particularly in post-Enlightenment contexts, religion is mainly associated strictly with codified beliefs and doctrines, something in turn heavily influenced by the doctrinal nature of Christianity (and especially protestant Christianity with the emphasis on salvation by faith alone). This differs markedly from religions like Buddhism, where practice, experience, and a phenomenological approach to understanding mind and reality are central, rather than the adherence to orthodox beliefs. The idea that skepticism is antithetical to religion is born out of a culturally-condition view of religion. Buddhism exemplifies how a religious framework can coexist with, or even promote, a skeptical approach to understanding nature (see the Kalama Sutta). It does not commit to a dogmatic worldview but instead encourages inquiry and direct personal experience as paths to enlightenment. This is, of course, why it is often said that Buddhism is not a religion but a philosophy, although that is also not quite true, as it's ultimate aim is liberation from worldly existence, which is clearly a religious one.

This highlights how deep-seated cultural assumptions can influence the interpretations of non-Western philosophies and religion. But it's also inevitable, to some extent, because of the role of belief in faith is often viewed as both a gift and a response to God's grace. It involves an assent to the doctrines taught by the church and a trust in God's promises. This framework can lead to an understanding of religion as essentially a belief-based system, where the right belief is the key to spiritual fulfillment and salvation. In contrast Buddhism place a greater emphasis on practices such as meditation, moral living, and the direct experience of insights about the nature of reality. Significant that the first item on the Buddhist Eightfold Path is 'right view' (samma dhitthi) rather than 'right belief' (orthodoxy). That's not to say that faith is not also important in Buddhism, as it is, but it is also counter-balanced by an existential perspective which is often missing in dogmatic religions. -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

I've heard it said that Zen Buddhism is a "practice" not a religion. But it is a "practice" with specific beliefs and group requirements or expectations. Years ago, at a hippie-like alternative church deep in the US "bible belt", I experimented with Alpha-Theta meditation, which omitted the associated Hindu/Buddhist beliefs, and focused solely on reaching a "deep, meditative, hypnotic-like state". An EEG machine was used to verify the brain-wave status during meditation.This differs markedly from religions like Buddhism, where practice, experience, and a phenomenological approach to understanding mind and reality are central, rather than the adherence to orthodox beliefs. — Wayfarer

Was that too quick & technical to qualify as a "practice"? Anyway, I enjoyed the waking-sleep relaxation, but never achieved any remarkable insights or feelings. I guess I didn't practice enough, but EEG readings are not the kind of feedback that would keep me coming back. Repetitive Practice requires emotional commitment to some personal goal, and belief that the goal is achievable. Probably, my intellectual curiosity was not sufficient for devoting my life to the practice of "wasting time". :smile:

Buddhism is variously understood as a religion, a philosophy, or a set of beliefs and practices based on the teachings of the Buddha,

https://tricycle.org/beginners/

"As the old joke goes, a tourist asked a New Yorker how do you get to Carnegie Hall. And the answer was: Practice! Practice! Practice!"

Buddhist Metaphysics :

Although mainstream Buddhism is a “form of mystical idealism”, the author says that it’s actually “a heady mixture of four quite distinct and contrasting metaphysical systems” : Common-sense Realism ; Theistic Spirituality ; Phenomenalism ; and Mystical Idealism.

https://bothandblog7.enformationism.info/page21.html

Why Buddhism is Enlightening :

This book is not recommending conversion to one of the various Asian religions that evolved from the Buddha’s teachings. Instead, he sees secular Meditation as a viable technology for taking command of our lives, and for avoiding or alleviating the psychological suffering — mostly Freudian neuroses — that plague many people today.

https://bothandblog6.enformationism.info/page51.html

How To Practice Stoicism :

“A Stoic is someone who transforms fear into prudence, pain into transformation, mistakes into initiation, and desire into undertaking.” — N.N.Taleb

https://mindfulstoic.net/how-to-practice-stoicism-an-introduction-12-stoic-practices/

Note --- Although it's closer to my own Western worldview, I don't consciously practice Stoicism. Perhaps because I'm not aware of any personal neuroses that need to be "transformed" into more positive behaviors. -

Wayfarer

26.2kI've published a Medium essay The Timeless Wave, on the philosophical interpretations of the double-slit experiment. (May require registration on medium but can be accessed for free thereafter.) I expect there will be disagreements but must say I'm happy with the quality of the prose.

Wayfarer

26.2kI've published a Medium essay The Timeless Wave, on the philosophical interpretations of the double-slit experiment. (May require registration on medium but can be accessed for free thereafter.) I expect there will be disagreements but must say I'm happy with the quality of the prose.

@Tom Storm @Banno -

180 Proof

16.5k:clap: Well done, sir. As a layman I'm more or less an Everettian (as per D.Deutsch's version of the MWI) but your summary of the issues with CI & QBism is succinctly spot on. Nonetheless, to paraphrase the Persian poet Rumi: there would be no fool's gold, were there no fool (i.e. "bad philosophy" (anti-realism) —> bad physics —> bad philosophy...) To wit:

180 Proof

16.5k:clap: Well done, sir. As a layman I'm more or less an Everettian (as per D.Deutsch's version of the MWI) but your summary of the issues with CI & QBism is succinctly spot on. Nonetheless, to paraphrase the Persian poet Rumi: there would be no fool's gold, were there no fool (i.e. "bad philosophy" (anti-realism) —> bad physics —> bad philosophy...) To wit:

:nerd:

-

Wayfarer

26.2kI'll refer to Phillip Ball, The Many Problems of Many Worlds.

Wayfarer

26.2kI'll refer to Phillip Ball, The Many Problems of Many Worlds.

What the MWI really denies is the existence of facts at all. It replaces them with an experience of pseudo-facts (we think that this happened, even though that happened too). In so doing, it eliminates any coherent notion of what we can experience, or have experienced, or are experiencing right now. We might reasonably wonder if there is any value — any meaning — in what remains, and whether the sacrifice has been worth it.

Every scientific theory (at least, I cannot think of an exception) is a formulation for explaining why things in the world are the way we perceive them to be. This assumption that a theory must recover our perceived reality is generally so obvious that it is unspoken. The theories of evolution or plate tectonics don’t have to include some element that says “you are here, observing this stuff”; we can take that for granted.

In the end, if you say everything is true (i.e. every possible outcome has happened), you have said nothing.

But the MWI refuses to grant it. Sure, it claims to explain why it looks as though “you” are here observing that the electron spin is up, not down. But actually it is not returning us to this fundamental ground truth at all. Properly conceived, it is saying that there are neither facts nor a you who observes them.

It says that our unique experience as individuals is not simply a bit imperfect, a bit unreliable and fuzzy, but is a complete illusion. If we really pursue that idea, rather than pretending that it gives us quantum siblings, we find ourselves unable to say anything about anything that can be considered a meaningful truth. We are not just suspended in language; we have denied language any agency. The MWI — if taken seriously — is unthinkable.

Its implications undermine a scientific description of the world far more seriously than do those of any of its rivals. The MWI tells you not to trust empiricism at all: Rather than imposing the observer on the scene, it destroys any credible account of what an observer can possibly be. Some Everettians insist that this is not a problem and that you should not be troubled by it. Perhaps you are not, but I am. — Phillip Ball

As I understand it - and I think I do understand it - the entire genesis of Everett's theory was the simple question: what if the wavefunction collapse doesn't occur? What would that entail?

According to an article in Scientific American, The Many Worlds of Hugh Everett (referring to a biography of him by that name).

Everett’s scientific journey began one night in 1954, he recounted two decades later, “after a slosh or two of sherry.” (Incidentally, he died an alcoholic and left instructions that his ashes be put our with the trash) He and his Princeton classmate Charles Misner and a visitor named Aage Petersen (then an assistant to Niels Bohr) were thinking up “ridiculous things about the implications of quantum mechanics.” During this session Everett had the basic idea behind the many-worlds theory, and in the weeks that followed he began developing it into a dissertation. ....

Everett addressed the measurement problem by merging the microscopic and macroscopic worlds. He made the observer an integral part of the system observed, introducing a universal wave function that links observers and objects as parts of a single quantum system. He described the macroscopic world quantum mechanically and thought of large objects as existing in quantum superpositions as well. Breaking with Bohr and Heisenberg, he dispensed with the need for the discontinuity of a wave-function collapse.

Everett’s radical new idea was to ask, What if the continuous evolution of a wave function is not interrupted by acts of measurement? What if the Schrödinger equation always applies and applies to everything—objects and observers alike? What if no elements of superpositions are ever banished from reality? What would such a world appear like to us?

Everett saw that under those assumptions, the wave function of an observer would, in effect, bifurcate at each interaction of the observer with a superposed object.

And what problem does this daring adventure in fantasy purportedly solve? Why, that would be the metaphysical issue implied by the so-called 'wavefunction collapse'. At the expense of avoiding the apparent 'woo factor' involved in the measurement problem, we simply declare that it doesn't. At a considerable cost.

I wonder what David Deutsche's (probably unconscious) metaphysical commitments are, such that he views anyone who questions MWI with about the same scorn Richard Dawkins saves for creationists. Of course, I know he's one of the Smartest People in the World, but still, I can't help but think that something is seriously amiss here. -

180 Proof

16.5k

180 Proof

16.5k

Listen to the discussion in the first youtube video I posted where Deutsch makes it clear he is a scientific realist (i.e. anti-antirealist ... anti-instrumentalist). The genesis of Hugh Everett's thesis is scientifically irrelevant and I lost interest immediately with Phillip Ball's idiotic / disingenuous first sentence "What the MWI really denies is the existence of facts at all." Again:I wonder what David Deutsche's(probably unconscious)metaphysical commitments are — Wayfarer

'bad philosophy' (anti-realism) —> bad physics —> bad philosophy (woo-woo) — 180 Proof -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe point is that the many worlds interpretation wants to deny the wavefunction collapse to preserve scientific realism. To this end it starts from the premise that every possible measurement outcome really occurs, although in the world we are in, we only see one of them. Is that not the case?

Wayfarer

26.2kThe point is that the many worlds interpretation wants to deny the wavefunction collapse to preserve scientific realism. To this end it starts from the premise that every possible measurement outcome really occurs, although in the world we are in, we only see one of them. Is that not the case? -

Wayfarer

26.2kDeutsch says 'our perceptions are at the end of a long chain of physical processes'. He then starts on how to explain the apparently-inexplicable 'wavefunction collapse' by saying we don't really know how we know anything except indirectly. He says 'mathematical theorems are determined by physics' and that 'Physics is a theory of the reality of the world' - ergo the world is physical. So he's completely committed to physicalism as a paradigm. Which is more or less what I said - he's committed to MWI because it obviates the need for the 'wavefunction collapse' which seems mysterious ('woo' in your language) and so, what needs to be avoided. He then accuses Copenhagen etc of 'leading to solipsism'. I think I'll leave it there, and thanks for your feedback.

Wayfarer

26.2kDeutsch says 'our perceptions are at the end of a long chain of physical processes'. He then starts on how to explain the apparently-inexplicable 'wavefunction collapse' by saying we don't really know how we know anything except indirectly. He says 'mathematical theorems are determined by physics' and that 'Physics is a theory of the reality of the world' - ergo the world is physical. So he's completely committed to physicalism as a paradigm. Which is more or less what I said - he's committed to MWI because it obviates the need for the 'wavefunction collapse' which seems mysterious ('woo' in your language) and so, what needs to be avoided. He then accuses Copenhagen etc of 'leading to solipsism'. I think I'll leave it there, and thanks for your feedback. -

Relativist

3.6k

Relativist

3.6k

This makes perfect sense. But the following does not:I am making clear the sense in which perspective is essential for any judgement about what exists — even if what we’re discussing is understood to exist in the absence of an observer, be that an alpine meadow, or the Universe prior to the evolution of h. sapiens. The mind brings an order to any such imaginary scene, even while you attempt to describe it or picture it as it appears to exist independently of the observer. — Wayfarer

This seems to contradict the bolded portion of the first quote. I could grant that a subjective perception of some aspect of reality exists only if it is perceived, but this doesn't account for your statement of neither existing nor not existing".In reality, the supposed ‘unperceived object’ neither exists nor does not exist. Nothing whatever can be said about it. — Wayfarer

Fair point. We do need to take our subjectivity into account. But this doesn't preclude our determining some objective truths about reality. You seem to acknowledge that the universe exists. This is an objective truth, even though the words in the statement rely on minds to give them meaning.What I’m calling attention to is the tendency to take for granted the reality of the world as it appears to us, without taking into account the role the mind plays in its constitution. — Wayfarer

I don't understand this. Truth is not subjective, although there are truths about subjective things. Objective truth: "The universe exists". Truth about something subjective: "The images of the 'Pillars of Creation' produced by the Webb telescope are beautiful".This oversight imbues the phenomenal world — the world as it appears to us — with a kind of inherent reality that it doesn’t possess. This in turn leads to the over-valuation of objectivity as the sole criterion for truth.

I can accept this if "unseen realities"=The subjective perspective of something in the world.the existence of all such supposedly unseen realities still relies on an implicit perspective. — Wayfarer

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum