-

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kThis is a spin-off from the anti-realism thread, and particularly some exchanges among @fdrake, @Leontiskos, and myself. I could have just posted it there, but I didn't.

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kThis is a spin-off from the anti-realism thread, and particularly some exchanges among @fdrake, @Leontiskos, and myself. I could have just posted it there, but I didn't.

I want to describe an approach to philosophical issues, not to take a side for or against it, but to highlight it, indicate the ramifications of it, sometimes noticed and sometimes not, and maybe clarify some of our discussions a little.

There are two styles of the approach, at least two I've noticed: first, there's the Model Building style; second, the Deflationary style.

What do models model exactly? It's not a hard question; the answer is behavior.

Say you're building a model of a farmyard that includes a duck. Your model duck should look like a duck, waddle like a duck, quack like a duck, and so on. The important thing is that for each way a duck behaves that you're interested in, your model duck has a correlating behavior.

When explaining your model to someone else, you can point at the model duck and say, by a sort of metonymy, "here's the duck". You can further point out that it quacks and waddles, and demonstrate that it does.

Now, we could ask whether your model duck quacks, or "quacks". There are some options here. One is to say that both the real duck and the model duck quack, the real duck in one way and the model in another. And if you follow that logic where it leads, you might as well say your model duck is a duck, not a "duck". You were already inclined to, but you don't really have to treat it as a manner of speaking.

So what about the duck you were modeling? Here again, the important thing is that it has all the right features to be a duck, the appearance and the waddling and the quacking. Maybe there's still some divergence, but the question is whether the duck being modelled could possibly exhibit any behavior that could not be modelled. That is, whether there is any reason, in principle, not to expect that the models can be kept in synch.

For the moment, I'm inclined to assume that there is not. And if not, it's not clear in what sense we would distinguish the model duck from a duck.

That might seem like a problem, or at least a little odd, but my claim is that this is quite natural to the model-building impulse. It's behavior that matters, and model-building is deliberately agnostic, as we might say, about being.

In fact, past a certain point, model-building is not just agnostic as regards being, but questions of being become invisible to it. All there is, is behavior. Duck-typing is the only typing. A thing is what it does.

For the deflationary style, this is the point. In the model-building style, being just disappears, and whenever you reach for it you find more behavior to incorporate into the model. But for the deflationist, ruling out the issue of being is the first move. Model-builders lose track of being; deflationists flee it and end up with behavior.

There might be trouble about whose behavior we're talking about in any given model. For example, are numbers bundles of behavior like ducks, or are numbers something we do? (In fact, it appears there are some people who believe you can take one more step and proclaim something amounting to agnosticism about whose behavior, but that's less common.) Mostly this doesn't seem to be a hard call for deflationists. Meaning is something we do, numbers are something we do, radioactivity is something atoms do.

The question of whose behavior comes up eventually in every single thread here that touches on metaphysics or language, and probably some others I don't know about. But that debate is sometimes really two debates: in one everyone agrees that something is a bundle of behavior and the question is whether it's ours or something else's; but in the other the disagreement is about whether something is a bundle of behavior or a being, whatever that might mean.

And my point is that this latter form of disagreement is all but invisible to the model-building approach (and anathema to the deflationist), which will only ever find more behavior to model. (And the former sort of disagreement ― having agreed on the bundle-of-behavior part ― may be intractable because there's so much agreement, all that's left is personal taste.)

And that's why I'm posting. Much as I've enjoyed building models over the years, I'm a little uncomfortable that the approach I'm describing has a sort of blindness. Whenever a question is raised about what something is, it is immediately rewritten as a question about how that thing behaves, so that we can get started modelling that bundle of behavior.

Maybe that's genuinely the best way to go, and good riddance to questions of being, as the deflationist would have it.

But I have some doubts.

(A deflationist reading this will likely wonder what all the fuss is about, what questions of being could possibly be interesting or important? I expect we'll get to that, but in the meantime I'll just point out that this is a full endorsement of my claim, that there may be other ways of doing philosophy that, to the deflationist, are not even wrong, not just invisible, but plain unimaginable.) -

Wayfarer

26.1kSay you're building a model of a farmyard that includes a duck. Your model duck should look like a duck, waddle like a duck, quack like a duck, and so on. The important thing is that for each way a duck behaves that you're interested in, your model duck has a correlating behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

Wayfarer

26.1kSay you're building a model of a farmyard that includes a duck. Your model duck should look like a duck, waddle like a duck, quack like a duck, and so on. The important thing is that for each way a duck behaves that you're interested in, your model duck has a correlating behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

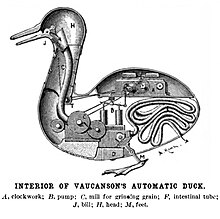

Like this, you mean?

Much as I've enjoyed building models over the years, I'm a little uncomfortable that the approach I'm describing has a sort of blindness. Whenever a question is raised about what something is, it is immediately rewritten as a question about how that thing behaves, so that we can get started modelling that bundle of behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

Like this, you mean? -

jkop

1k..what questions of being could possibly be interesting or important? — Srap Tasmaner

jkop

1k..what questions of being could possibly be interesting or important? — Srap Tasmaner

For example, can a model of conscious verbal behavior be conscious?

A model of a duck is arguably not a duplication of a duck. It's a model or simulation based on a selection of observed and known behaviors. A model of duck depends on what we observe and know of ducks. For some anti-realists, also ducks depend on us. I think ducks are not so dependent on us, but when we speak or think about ducks we construct models based on what we observe and know.

Likewise, we construct models based on what we observe and know of our conscious verbal behavior. But being conscious and modeling something is different from being the model. -

Mapping the Medium

366A model of duck depends on what we observe and know of ducks. For some anti-realists, also ducks depend on us. — jkop

Mapping the Medium

366A model of duck depends on what we observe and know of ducks. For some anti-realists, also ducks depend on us. — jkop

Yes. ... This model of a duck is not so much a duck as it is a human-reflected duck(?). When we filter anything through human perception, we attach characteristics and behaviors that to it that are not at all the same as through the perception of a duck.

Have you ever had someone in your life tell you that you've 'changed', and later both of you discovering that it wasn't that you had changed so much but that the person had never actually invested the time and energy to 'know' you better. That person, in the interest of limited perception time, had refected their own biases into the conclusions they had reached.

If I had a dollar for every time I have been cordial towards a man and he took it as my being attracted to him. .... But that doesn't mean that I will stop being cordial. THAT is who I am, not the woman coming on to him that he has modeled in his mind based on his past experiences or hopeful future ones. -

J

2.4kFirst of all, good OP! You've got your eye on something important in philosophical method.

J

2.4kFirst of all, good OP! You've got your eye on something important in philosophical method.

the question is whether the duck being modelled could possibly exhibit any behavior that could not be modelled. That is, whether there is any reason, in principle, not to expect that the models can be kept in synch.

For the moment, I'm inclined to assume that there is not. — Srap Tasmaner

Do you think a model duck can eat, digest, excrete, and reproduce? These are all behaviors. For myself, I can just about imagine, in some future state of technology, a model duck doing the first three, or at least imitating them in a way that would be indistiguishable from what a live duck does, but not the fourth. And this connects with the deeper question you're raising, about whether behavioral models neglect "being," or life, or consciousness. It may turn out that consciousness is a feature only of living things, in which case the model won't have it. I suppose that would not be an issue if "behavior" is defined exclusively as what is visible to the naked eye. Is this a good definition, though?

Whenever a question is raised about what something is, it is immediately rewritten as a question about how that thing behaves, so that we can get started modelling that bundle of behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

I'm curious to know which philosophers you have in mind (not on TPF!). I don't seem to run into this approach very often, in my reading. -

Mww

5.4kA deflationist reading this will likely wonder what all the fuss is about…. — Srap Tasmaner

Mww

5.4kA deflationist reading this will likely wonder what all the fuss is about…. — Srap Tasmaner

That’d be me, on the one hand, insofar as that which is, is given. But it is, on the other hand, the systemic function of my intelligence to internally model that which is given, in such a way as to accommodate my experience of it.

But that’s not the point herein, is it. There must already be an internally constructed model in order for there to be a duck as such, in the first place. Otherwise, there is merely some thing given, subsequently determinable by its behaviors. Or, as they liked to say back in The Good Ol’ Days, by its appearance to the senses.

So why do I need to model a real duck, if I’ve already done it? The duck I physically manufacture and situate in an environment adds nothing to my experience. Even if I discover the naturally real duck exhibits a behavior absent from my experience, and I manufacture Duck 2.0 incorporating it, the latest version must still have its own internal precursor, in order for its formally unperceived appearance to properly manifest.

————-

What do models model exactly? It's not a hard question; the answer is behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

While physically manufactured models model behavior, the necessarily antecedent intellectually assembled models, which do not exhibit naturally real behavior, do not. It still isn’t a hard question, it just doesn’t have a single, all-encompassing answer. -

frank

18.9kAll there is, is behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

frank

18.9kAll there is, is behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

You started with the concept of a duck though. -

T Clark

16.1kWhat do models model exactly? It's not a hard question; the answer is behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

T Clark

16.1kWhat do models model exactly? It's not a hard question; the answer is behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

If you're modelling a farmyard, it's the overall behavior of the system that matters, not the behavior of individual elements. For that, the relationships among the behaviors of the various elements are more important than the behaviors themselves. You start off with initial conditions which are then modified based on internal time rates of change for each element and external defined relations with other elements. The duck model you are discussing just provides the initial conditions. -

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k -

LuckyR

726The purpose of creating a model duck within the model farmyard is to analyze the interaction between the duck and other entities within the farmyard. Not to analyze the duck itself. If analysis of an individual in isolation is one's goal, you use a real duck, ie there is no role for a model.

LuckyR

726The purpose of creating a model duck within the model farmyard is to analyze the interaction between the duck and other entities within the farmyard. Not to analyze the duck itself. If analysis of an individual in isolation is one's goal, you use a real duck, ie there is no role for a model. -

Apustimelogist

946that there may be other ways of doing philosophy that, to the deflationist, are not even wrong, not just invisible, but plain unimaginable. — Srap Tasmaner

Apustimelogist

946that there may be other ways of doing philosophy that, to the deflationist, are not even wrong, not just invisible, but plain unimaginable. — Srap Tasmaner

Many people here have views here that directly contest mine which may be what you call "deflationary style" (but tell you the truth I read this and "deflationary style" and "model-building style" look exactly the same to me - so I would identify as both unless I have probably misread something).

I am so in at the deep end with my views about how I think brains work though that I think that all of these different philosophical views are implicitly a kind of behavioral-style because in my views, that is the only way that brains do understanding. All views are compatible with a "deflationary-style" on the meta-level insofar that all views are "deflationary-style" models from a brain perspective. I have a kind of view that brains, minds are actually kind of like scientific instrumentalists at the deepest level but this is not immediately obvious to us because of the richness and automaticity by which beliefs and thoughts and behaviors work. We take everything we do and say for granted without thinking about it. Again, this is the meta-level, and so to it applies to debates about realism and anti-realism - a dichotomy far too coarse and flimsy to say anything interesting without serious caveats.

On the floor-level what differentiates "deflationary-style" from "essentialists" and others? Perhaps we all have a choice of at what level to deflate or decompose explanations - some prefer deeper levels than others. On shallower levels, you can hold up concepts without trying to give deconstructing analysis of what it actually means to use the idea. You just assert it and say it is right and know that it is meaningful to you in a commonsense way. Like many people do with God and say they just believe in God and don't want to deconstruct what that actually means - often science would bring up difficult questions too - rather, they just settle that they don't need to go deeper, it doesn't need to be explained: it just is. The "deflationary-stylist" will go deeper and deeper deconstructing everything: it just isn't and there is no essential nature to anything. But whats the difference between shunning further deconstruction versus deconstructing and concluding on a deflation of the essential being? Not much difference to me. Sure, you may be able to create new empirical questions and testable parameters for God. But the meaning of the thing within our perspectives has no foundation beyond what - in my opinion - the instrumentalist mind or brain, and instrumentalist networks of interacting instrumentalist minds or brains. You can conceivably be right or wrong (approximately) in some sense about hypotheses concerning empirical structures under some very strict caveats. Is there a meaningful distinction between the "deflationary-stylist" and the "essentialist" beyond this? I guess not so much from my perspective. You just end up discussing the compatibility of your concepts and what you consider good standards for acceptance or rejection - which is the same story for all knowledge for instrumentalist brains.

Hmm, but what about discussing the compatibility of "deflation" and "essentialism"? What does one bring to the table that the other doesn't? This must be a genuine question. Perhaps at a guess it is a matter of something like accuracy vs. complexity trade-offs. Do you embrace the details (that would deflate the more abstract level of analysis [by effectively prioritizing the bottom level?]) or coarse over them (and effectively ignore them)? Insofar that truth is about accuracy in some sense then where you stand on these trade-offs affect what you say is "true" or "real" or "deflated" or "idealized" - but we can choose different levels for different things. Does that mean then that "true" and "real" is just a kind of abstract label in enacted, instrumentalist models? Yes, maybe. It becomes more tangible when there is an easy answer to whether your predictions are correct or not - but the more abstract you go, the more murky this gets and the less is resolved. And obviously another issue is that, you can change assumptions on the more abstract levels to change what the easy answer is on a more concrete level. Some people reject chairs exist. But again, changes on the abstract level are so murky - mereology doesn't really change our experiences of "chairs" because we all experience similar regularities about them, presumably due to the fact that there is an outside world beyond our perspectives or experiential purviews. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

That might seem like a problem, or at least a little odd, but my claim is that this is quite natural to the model-building impulse. It's behavior that matters, and model-building is deliberately agnostic, as we might say, about being.

I'm not sure about this whole "behavior/being" dichotomy. The old Scholastic adage is actum sequitur esse, "act follows on being." I have a few good quotes on this:

It is through action, and only through action, that real beings manifest or “unveil” their being, their presence, to each other and to me. All the beings that make up the world of my experience thus reveal themselves as not just present, standing out of nothingness, but actively presenting themselves to others and vice versa by interacting with each other. Meditating on this leads us to the metaphysical conclusion that it is the very nature of real being, existential being, to pour over into action that is self-revealing and self-communicative. In a word, existential being is intrinsically dynamic, not

static.

...by metaphysical reflection I come to realize that this is not just a brute fact but an intrinsic property belonging to the very nature of every real being as such, if it is to count at all in the community of existents. For let us suppose (a metaphysical thought experiment) that there were a real existing being that had no action at all. First of all, no other being could know it (unless it had created it), since it is only by some action that it could manifest or reveal its presence and nature; secondly, it would make no difference whatever to any other being, since it is totally unmanifested, locked in its own being and could not even react to anything done to it. And if it had no action within itself, it would not make a difference even to itself....To be real is to make a difference.

One of the central flaws in Kant’s theory of knowledge is that he has blown up the bridge of action by which real beings manifest their natures to our cognitive receiving sets. He admits that things in themselves act on us, on our senses; but he insists that such action reveals nothing intelligible about these beings, nothing about their natures in themselves, only an unordered, unstructured sense manifold that we have to order and structure from within ourselves. But action that is completely indeterminate, that reveals nothing meaningful about the agent from which it comes, is incoherent, not really action at all [or we might say, cannot be meaningfully ascribed to any "thing," i.e. as cause].

The whole key to a realist epistemology like that of St. Thomas is that action is the “self revelation of being,” that it reveals a being as this kind of actor on me, which is equivalent to saying it really exists and has this kind of nature = an abiding center of acting and being acted on. This does not deliver a complete knowledge of the being acting, but it does deliver an authentic knowledge of the real world as a community of interacting agents—which is after all what we need to know most about the world so that we may learn how to cope with it and its effects on us as well as our effects upon it. This is a modest but effective relational realism, not the unrealistic ideal of the only thing Kant will accept as genuine knowledge of real beings, i.e., knowledge of them as they are in themselves independent of any action on us—which he admits can only be attained by a perfect creative knower. He will allow no medium between the two extremes: either perfect knowledge with no mediation of action, or no knowledge of the real at all.

W. Norris Clarke - "The One and the Many: A Contemporary Thomistic Metaphysics"

Or for an oldy-but-goody:

For all created things are defined, in their essence and in their way of developing, by their own logoi and by the logoi of the beings that provide their external context. Through these logoi they find their defining limits.

-St. Maximus the Confessor - Ambiguum 7

And my point is that this latter form of disagreement is all but invisible to the model-building approach (and anathema to the deflationist), which will only ever find more behavior to model. (And the former sort of disagreement ― having agreed on the bundle-of-behavior part ― may be intractable because there's so much agreement, all that's left is personal taste.)

Well, to my mind what makes deflationism distinct is that it essentially amounts to a sort of radical skepticism. Either there is no being to speak of, or being is entirely unknowable. However, the position that there is "only" or perhaps "most fundamentally" behavior/action is just process metaphysics. This isn't skeptical, it just views process as more fundamental than susbstance (thing-hood). I'll admit, I was quite taken with this view for a while. Here is a good argument for it:

To be a substance (thing-unit) is to function as a thing-unit in various situations. And to have a property is to exhibit this property in various contexts. ('The only fully independent substances are those which-like people-self-consciously take themselves to be units.)

As far as process philosophy is concerned, things can be conceptualized as clusters of actual and potential processes. With Kant, the process philosopher wants to identify what a thing is with what it does (or, at any rate, can do). After all, even on the basis of an ontology of substance and property, processes are epistemologically fundamental. Without them, a thing is inert, undetectable, disconnected from the world's causal commerce, and inherently unknowable. Our only epistemic access to the absolute properties of things is through inferential triangulation from their modus operandi-from the processes through which these manifest themselves. In sum, processes without substantial entities are perfectly feasible in the conceptual order of things, but substances without processes are effectively inconceivable.

Things as traditionally conceived can no more dispense with dispositions than they can dispense with properties. Accordingly, a substance ontologist cannot get by without processes. If his things are totally inert - if they do nothing - they are pointless. Without processes there is no access to dispositions, and without dispositional properties, substance lie outside our cognitive reach. One can only observe what things do, via their discernible effects; what they are, over and above this, is something that always involves the element of conjectural imputation. And here process ontology takes a straight-forward line: In its sight, things simply are what they do rather, what they dispositionally can do and normally would do.

The fact is that all we can ever detect about "things" relates to how they act upon and interact with one another - a substance has no discernible, and thus no justifiably attributable, properties save those that represent responses elicited from it in interaction with others. And so a substance metaphysics of the traditional sort paints itself into the embarrassing comer of having to treat substances ·as bare (propertyless) particulars [substratum] because there is no nonspeculative way to say what concrete properties a substance ever has in and of itself. But a process metaphysics is spared this embarrassment because processes are, by their very nature, interrelated and interactive. A process-unlike a substance -can simply be what it does. And the idea of process enters into our experience directly and as such.

Nicholas Rescher - "Process Metaphysics: An Introduction to Process Philosophy

However, we don't generally tend to talk about processes occurring involving "nothing in particular," and a weakness of process philosophy is its ability to explain why some things do appear to make up self-organizing, organic wholes, which are even directed towards aims. It can certainly do so, but successful attempts at this I've seen tend to conform to the old Aristotelian framework of unity, which is fine, since in some sense Aristotle's philosophy is one of process (although still focused on the being of substances), it's just that this tends to get lost in simplifications.

Hegel has some useful things to say here too:

Hegel's basic demarche in both versions [of the Logic] is to trade on the incoherencies of the notions of the thing derived from this modern epistemology, very much as in the PhG. The Ding-an-sich is first considered: it is the unity which is reflected into a multiplicity of properties in its relation to other things, principally the knowing mind. But its properties cannot be separated from the thing in itself, for without properties it is indistinguishable from all the others. We might therefore say that there is only one thing in itself, but then it has nothing with which to interact, and it was this interaction with others, which gave rise to the multiplicity of properties. If there is only one thing-in-itself, it must of itself go over into the multiplicity of external properties. If we retain the notion of many, however, we reach the same result, for the many can only be distinguished by some difference of properties, hence the properties of each cannot be separated from it, it cannot be seen as simple identity.

Thus the notion of a Ding-an-sich as unknowable, simple substrate, separate from the visible properties which only arise in its interaction with others, cannot be sustained. The properties are essential to the thing, whether we look at it as one or many. And so Hegel goes over to consider the view which makes the thing nothing but these properties, which sees it as the simple coexistence of the properties. Here is where the theories of reality as made up of ' matters' naturally figure in Hegel's discussion.

But the particular thing cannot just be reduced to reduced to a mere coexistence of properties. For each of these properties exists in many things. In order to single out a particular instance of any property, we have to invoke another property dimension. If we want to single out this blue we have to distinguish it from others, identify it by its shape, or its position in time and space, or its relation to other things. But to do this is to introduce the notion of the multipropertied particular, for we have something now which is blue and round, or blue and to the left of the grey, or blue and occurring today, or something of the sort.

-Charles Taylor - Hegel -

Leontiskos

5.6kThis is a spin-off from the anti-realism thread — Srap Tasmaner

Leontiskos

5.6kThis is a spin-off from the anti-realism thread — Srap Tasmaner

<This one>, for those who are interested.

For the deflationary style, this is the point. In the model-building style, being just disappears, and whenever you reach for it you find more behavior to incorporate into the model. But for the deflationist, ruling out the issue of being is the first move. Model-builders lose track of being; deflationists flee it and end up with behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

Much as I've enjoyed building models over the years, I'm a little uncomfortable that the approach I'm describing has a sort of blindness. Whenever a question is raised about what something is, it is immediately rewritten as a question about how that thing behaves, so that we can get started modelling that bundle of behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

Supposing Aristotle is a primary source of being/essence considerations, we should ask why he disagrees with the "behaviorist." Let me give some ideas off the top of my head.

First, going back to what I said to , "But activity is only half the picture. The other half is receptivity..." In the first place, "behavior" is a bit loose. If we model grass with artificial turf, are we modeling behavior? Does grass behave? Only metaphorically. For Aristotle the proper term is not behavior, but act/actuality (energeia or entelecheia). And the first Aristotelian objection to "behaviorism" and @fdrake is that there is not only act; there is also potency/potentiality (dunamis) (cf. SEP). For example, humans can die and female ducks can become pregnant. These are potentialities, not behaviors or acts.

For Aristotle, with natural entities we begin by observing their motion/change, both the way they move/change themselves and they way they are moved/changed by other things (and this pertains loosely to act and potency). From these observations we move to infer powers and then essence/whatness. Apparently your behaviorist thinks it is otiose to go beyond a consideration of motion/change. Why does Aristotle disagree?

He disagrees because powers explain motion/change, and essence/whatness explains powers. Truly explanatory principles are at play. To give an example, suppose we observe a human infant. As it grows it begins to speak English. Why does it speak at one time and not at another? Because it has a power to speak English. We then note that some children speak Spanish, and others other languages, and others multiple languages. We deduce that the English-speaking child not only has a power to speak English, but it also has the power to speak, or rather learn, Spanish. It has the power of language acquisition. And what can we conclude from the fact that humans can speak and learn languages, including formal mathematical and computational languages, as well as cultural languages? We can conclude that they are rational, i.e. they have the ability to compose and divide with their mind in a way that produces knowledge. For Aristotle this is a deeper explanatory level, namely that the essence/whatness of human beings is "rational animal."

Now suppose a god is going to recreate the duck, perhaps as Aulë created the dwarves. Will it be sufficient to know how ducks behave? I don't think so. I think one will also need to know how ducks respond to the behavior of other things, such as the fox that eats duck (including how it responds to having its neck broken and being digested). And one will also need to understand not only the internal proportion of duck "behaviors," but also the principles, causes, and explanations of the behaviors, which dictate the manner in which different kinds of behaviors interact (as well as the proportions and interactions between these powers). For example, ducks have a desire and power to mate, eat, survive, migrate, etc. These are more generalized than particular, isolated behaviors. Finally, when we say "duck" we are thinking of a coherent totality of properties, behaviors, environmental interactions, and potentialities that make up a unified whole, and this is the essence/whatness of a duck. It underscores the fact that there is one thing/substance to which all of these different facts are attributable, and that this substance has a determinate nature that differs from other substances, such as foxes or fish.

Interesting thread. :up:

P.S. To contrast "being" with "behavior" is a bit odd, given that behaviors have being (and also truth in relation to @fdrake's context). The reason Aristotle talks about substance, essence, and nature is because he thinks the being of the duck is different from the being of the quack, and both underlies and precedes it in an important way. 'Quack' is a verb, a behavior. 'Duck' is a noun, a substance that produces behavior. Can the behaviorist account for nouns? -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kAnyhow, what irks me about deflationist accounts is that they tend to ignore how radical a claim like "there is no such thing as truth, it's just a token in games/systems," is. It's on par with "the external world doesn't exist" or epistemic nihilism. A radical claim needs good support. But in general, arguments for deflationism just tend to rely on the same tired false dichotomy. Either knowledge is the "view from nowhere," sign systems as the "mirror of nature," etc. or there is no truth and its "pragmatism all the way down" (which leads straightforwardly to an infinite regress). Not-A, so B. But these aren't are only options. And to try to make these appear to be the only two options, they tend to backwards project the epistemology of a narrow period in the history of analytic philosophy back on to the whole history of philosophy.

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kAnyhow, what irks me about deflationist accounts is that they tend to ignore how radical a claim like "there is no such thing as truth, it's just a token in games/systems," is. It's on par with "the external world doesn't exist" or epistemic nihilism. A radical claim needs good support. But in general, arguments for deflationism just tend to rely on the same tired false dichotomy. Either knowledge is the "view from nowhere," sign systems as the "mirror of nature," etc. or there is no truth and its "pragmatism all the way down" (which leads straightforwardly to an infinite regress). Not-A, so B. But these aren't are only options. And to try to make these appear to be the only two options, they tend to backwards project the epistemology of a narrow period in the history of analytic philosophy back on to the whole history of philosophy.

Another major assumption in play is generally that reason is just something like "the process by which one moves from premise to premise," or computation. So, reason, now neutered, has none of the ecstatic, transcendent properties that were once ascribed to it.

Language, systems, games, all become what we know instead of a means of knowing. Well, that's one position to take, but it hardly seems like the sort of thing that can be assumed as a premise, particularly if the conclusion is going to be so radical.

As I put it before:

I will not assert that such a position can be convincingly demonstrated within any specific language game. After all, the very assertion in question is the ability of language games to join us to what lies outside them—metaphysical truth. To be sure, I could provide an argument that demonstrates my conclusion. I might even be able to do so using axioms that many readers would find to be “self-evident.” Yet, per the deflationist, this would merely express what is “true” within one conceptual scheme. Reason has become a fly trapped within the isolated fly bottles of discrete language games.

Here, it might be helpful to end by reflecting on G.K. Chesterton’s discussion of the “madman” in Orthodoxy. As Chesterton points out, the madman, can always make any observation consistent with his delusions. “If [the] man says… that men have a conspiracy against him, you cannot dispute it except by saying that all the men deny [it]; which is exactly what conspirators would do. His explanation covers the facts as much as yours.” Expressing the man’s error is not easy; his thoughts are consistent. They run in a “perfect but narrow circle. A small circle is quite as infinite as a large circle… though… it is not so large.” The man’s account “explains a large number of things, but it does not explain them in a large way.” For Chesterton, the mark of madness is this combination of “logical completeness and a spiritual contraction.” In the same way, a view of truth that is limited to the confines of individual language games explains truth in a “small way.” Reason is no longer ecstatic, taking us beyond what we already are. Rather it paces in tight, isolated circles. On such a view, reason represents not a bridge, the ground of the mind’s nuptial union with being, but rather the walls of a perfect but hermetically sealed cell. -

Leontiskos

5.6kWhat do models model exactly? It's not a hard question; the answer is behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

Leontiskos

5.6kWhat do models model exactly? It's not a hard question; the answer is behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

Well, what is the standard "model duck"? A duck decoy. And a decoy does not model behavior, it models form. The form then mediates expected behaviors, which is why the decoy is successful. In real life the metonymy of the decoy functions in virtue of the relation between the outward form/characteristics and the internal principles of action and passion. So if I see a decoy tiger I will become fearful because tigers have the power to kill me, and the thing before me looks like a tiger. If there were no difference between a tiger and its fearful behavior I would already be dead upon encountering one.

-

Edit:

Much as I've enjoyed building models over the years, I'm a little uncomfortable that the approach I'm describing has a sort of blindness. Whenever a question is raised about what something is, it is immediately rewritten as a question about how that thing behaves, so that we can get started modelling that bundle of behavior.

Maybe that's genuinely the best way to go, and good riddance to questions of being, as the deflationist would have it. — Srap Tasmaner

I suppose if we stretch the word "behavior" quite far, such that it includes everything about a duck, then there can be no difference between behavior and being - no 'being' of the duck that is not captured by its behavior. And of course we may need to hone in on exactly what the OP means by 'being', or where that distinction is coming from. But I am in general wary of stretching the meaning of words in this way (whether with fdrake we stretch "social construction" to include the findings of the hard sciences, or with the behaviorist we stretch "behavior" to include potentialities such as passions, powers, and organism-unity). Usually that kind of stretching warps our thinking even where it doesn't lead us altogether astray.

Maybe this would be a useful way to think about it... Suppose a god like Aulë attempts to create a perfect replica of a living duck. What is the test of his success? We give him two "ducks," but he lacks knowledge of which one he created. We impose no limits on his investigation: he has as much time as he wants, and he can explore as he pleases, including vivisection and dissection. If he truly cannot tell the difference, then he has succeeded in creating a duck. And then we should ask: supposing he does succeed in creating an indiscernible replica, are all the criteria he ended up using in order to try to discern which duck is his, criteria which limit themselves to purely behavioral considerations? I would have an extremely hard time believing that they would be.

(So in order to reject the "behaviorism" of the OP I don't think we need to say that there are realities of substances that in no way manifest empirically, but I think it is right to reject it on the basis that there are realities of substances which manifest empirically—in "behavior," say,—but yet are not themselves properly called behaviors. A simple example would be the form/characteristics of the wings, which allow for flight. This form is not a behavior, but it is an intrinsic property of ducks and a prerequisite for the flying-behavior of ducks.) -

Heiko

527Much as I've enjoyed building models over the years, I'm a little uncomfortable that the approach I'm describing has a sort of blindness. Whenever a question is raised about what something is, it is immediately rewritten as a question about how that thing behaves, so that we can get started modelling that bundle of behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

Heiko

527Much as I've enjoyed building models over the years, I'm a little uncomfortable that the approach I'm describing has a sort of blindness. Whenever a question is raised about what something is, it is immediately rewritten as a question about how that thing behaves, so that we can get started modelling that bundle of behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

The model describes existence, the way something is. It does not describe how it is to be a duck. Is that a blind spot? I don't think so - I am not a duck.... -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k

The issue, I see it, becomes significantly harder the more complicated a model is.

If the model is about a particle, well, there's is only so much tinkering you can do, beyond a point, given the simplicity involved, the thing described by the model, is probably a very good approximation to the thing itself, again because it is so simple.

And much to our great Suprise, the model in simple systems show quite mind-boggling behavior, that we are still debating the foundations of such experiments 100 years later, apparently no closer to a resolution now than back then.

But this complexity just becomes overwhelmingly difficult with things like insects, much less ducks.

We have very little reason to believe that just because a thing we create walks like a duck and quacks like one, is actually a duck (famous phrase aside).

At best, if we get the physiological properties more or less right, then we could say something about flying or ability to withstand environmental conditions.

But whatever is going on "behind the eyes", well, models will tell us almost nothing. What matters to understand a duck, is how the creature is interpreting the world. Behavior tells us almost nothing, especially is the duck is a mechanical construct, we are leaving out way too much. -

fdrake

7.2kThere are lots of ways this discussion could go. I'm just going to call someone who does metaphysics in the modelling approach a "functionalist", so that I've got one word for it. This choice of words corresponds to Sellars' philosophy of language being called functionalist, and also references old discussions on the site about related issues with @Isaac.

fdrake

7.2kThere are lots of ways this discussion could go. I'm just going to call someone who does metaphysics in the modelling approach a "functionalist", so that I've got one word for it. This choice of words corresponds to Sellars' philosophy of language being called functionalist, and also references old discussions on the site about related issues with @Isaac.

That is, whether there is any reason, in principle, not to expect that the models can be kept in synch.

For the moment, I'm inclined to assume that there is not. And if not, it's not clear in what sense we would distinguish the model duck from a duck. — Srap Tasmaner

I think there are a few readings of:

That is, whether there is any reason, in principle, not to expect that the models can be kept in synch.

I'll set up a bunch of symbols for stuff. The modelled entity, your duck, will be X. Its true set of behaviours will be B. The set of behaviours the model has accounted for will be B'. For now, I'll just assume that "accounting for" a behaviour is a very weak condition. The weak condition being that some subset of true behaviours b in B will be accounted for if they are mapped to some subset b' in B'. Roughly saying "this bunch of stuff the entity does in reality corresponds to that bunch of stuff in my model". That isn't saying anything about accuracy or internal coherence, just about correspondence.

Keeping in synch would be whenever some collection of behaviours b in B is discovered, then some corresponding set of behaviours b' in B' could be added.

With this really weak idea of correspondence, I agree with you that one should expect the models can in principle be kept in synch. Because any description of some behaviours b in B can be added as a b' in B'. It makes it hard, if not impossible, to find a counterexample in the functionalist approach's own terms. Which means the only way around that is a table flip - reframe the discussion.

And that's why I'm posting. Much as I've enjoyed building models over the years, I'm a little uncomfortable that the approach I'm describing has a sort of blindness. Whenever a question is raised about what something is, it is immediately rewritten as a question about how that thing behaves, so that we can get started modelling that bundle of behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

I think this impulse is the one that I have, yes. But I think that you can study mappings from B to B' for their own sake, which are metaphysical questions and epistemological ones. Those strands of questions, if I can be ridiculously presumptuous, might be corralled into the themes:

Metaphysics: what is it about the objects that allows them to be conceptualised as they are?

Epistemology: what is it about our concepts that makes them adequate to their objects?

And abstract answers in those domains of inquiry seem intelligible. Like general principles "a being is what it does", or "if two people's concepts of the same objects have inequivalent representative quantities, they instead have different concepts".

I think where a deflationist who also enjoys the functionalist paradigm above would disagree with a functionalist simpliciter is whether metaphysical {and maybe even epistemological} questions can only concern specific instances of the mapping between true behaviours and our descriptions. In effect, they disagree on whether the only salient questions about objects and concepts are of the modelling form. Which is roughly describing how things work, or describing {how describing things work} works.

There's more I want to say, but I'll need to figure out how to say it first. -

Heiko

527Does the model already contain all possible behaviours as possiblilities?

Heiko

527Does the model already contain all possible behaviours as possiblilities?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ae2ghhGkY-s -

Mapping the Medium

366But whatever is going on "behind the eyes", well, models will tell us almost nothing. What matters to understand a duck, is how the creature is interpreting the world. Behavior tells us almost nothing, especially is the duck is a mechanical construct, we are leaving out way too much. — Manuel

Mapping the Medium

366But whatever is going on "behind the eyes", well, models will tell us almost nothing. What matters to understand a duck, is how the creature is interpreting the world. Behavior tells us almost nothing, especially is the duck is a mechanical construct, we are leaving out way too much. — Manuel

I had posted this in another thread, but it seems like it might be helpful in this one too. If not, just bypass.

The link at TensorFlow Projector shows an artificial intelligence neural network LLM model. Scrolling over the data points shows how the model statistically correlates different words. There are also different ways to explore the model. The words have no relational correlation, only statistical. -

J

2.4kGood. Your "weak idea of correspondence" is an excellent limit case, calling into question whether we would even use the term "model" for a mapping that perfectly matched B and B' but provided neither structural, pictorial, nor functional resemblance -- no "accuracy or internal coherence." In what would that perfect matching consist? A mere stipulation that "b' is to count as b"?

J

2.4kGood. Your "weak idea of correspondence" is an excellent limit case, calling into question whether we would even use the term "model" for a mapping that perfectly matched B and B' but provided neither structural, pictorial, nor functional resemblance -- no "accuracy or internal coherence." In what would that perfect matching consist? A mere stipulation that "b' is to count as b"?

My earlier issue about whether a model of a duck could reproduce is, in contrast, a limit case in the opposite direction. It raises the same question about how b' and b relate, though. Is it reasonable to expect a modeling of B to not only mimic B perfectly, but also produce the same real-time results -- in this example, the fertilizing of an egg -- as B?

We may want to find a middle ground by being clearer about what counts as a behavior. Is it merely something I do? Do I "do" digestion? Blood circulation? These are strange ways of speaking, but what is it about the idea of behavior that seems to rule them out, and limit behavior to something that's . . . intended? deliberate? Is that the criterion?

I think where a deflationist who also enjoys the functionalist paradigm above would disagree with a functionalist simpliciter is whether metaphysical {and maybe even epistemological} questions can only concern specific instances of the mapping between true behaviours and our descriptions. In effect, they disagree on whether the only salient questions about objects and concepts are of the modelling form. Which is roughly describing how things work, or describing {how describing things work} works. — fdrake

Can you say more about this? I want to read you as saying that the deflationist doesn't countenance any abstract structural modeling but I'm not sure that's what you mean. -

fdrake

7.2kCan you say more about this? I want to read you as saying that the deflationist doesn't countenance any abstract structural modeling but I'm not sure that's what you mean. — J

fdrake

7.2kCan you say more about this? I want to read you as saying that the deflationist doesn't countenance any abstract structural modeling but I'm not sure that's what you mean. — J

What I meant is that the deflationist who is a functionalist refuses all questions which do not take the form of that modelling exercise about a prespecified entity. More general structural principles about connections between {roughly} being ( B ) and thought ( B' ) aren't even to be entertained. And moreover, that the only way of approaching specific instances of that connection is with these behavioural trappings.

My non-deflationist functionalist would approach specific instances of modelling like I specified, as a schema, but also be willing to entertain questions about the schema connecting objects to concepts through modelling - and how that connection relates to thought, being, and thought and being's interrelation.

The deflationist stops at the schema structure, it's a barrier to all further inquiry. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kSome quick hits, substance later. I guess.

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kSome quick hits, substance later. I guess.

I think this impulse is the one that I have — fdrake

Hey, so do I!

functionalist — fdrake

Right.

old discussions on the site about related issues with Isaac — fdrake

Yes, exactly. I've just now bothered to find that old exchange. Turns out I even used the phrase "bundle of behaviors" two years ago. Totally forgot I had shoehorned in a rant about sortals in that post.

And sortals were my logico-linguistic way of getting at

being/essence — Leontiskos

The word "essence" was very much in my mind writing the OP. Knew I could count on you to get it, @Leontiskos.

We don't talk this way much anymore. There was a time when "essence" was tidied up as "necessary and sufficient conditions" for ― for what? For truthfully applying a predicate, mostly. Being is scrunched down into the copula, and all that's left is being a value of a bound variable.

Where do Quine's bound variables live? In models. That was the whole point. If your model quantifies over ducks, you're committed to ducks as entities, no cheating. But the anti-metaphysics comes by flipping that around: ducks are entities just means you have a model in which you quantify over them. That implies "duck" has what amounts to a functionalist definition: what role ducks play in the model, how the duck nodes behave, interact with other nodes, and so on.

And the world is already such a place, a sort of real-life model ― as young Wittgenstein noticed about propositions.

And if that's the case, it provides a kind of justification for functionalist philosophy: we know this will work because we're just doing the same sort of thing the world is already doing. Sometimes there's a detour through neuroscience; we know our brains are already doing this sort of thing, and in philosophy we do more of that, for reasons that are a bit unclear.

Nevertheless, it's not exactly the relation "A is a model of B" that I was interested in. It's that functionalist "metaphysics". Now maybe this is a species of

process metaphysics — Count Timothy von Icarus

but those aren't waters I've swum in.

Either there is no being to speak of, or being is entirely unknowable. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, the deflationist view is that there's just nothing to say about the being of things, so don't bother. You can however talk a lot about their behavior, and in fact that's all there is to talk about.

if we stretch the word "behavior" quite far — Leontiskos

Oh yeah, really far. Most ordinary people aren't going to notice that the only consistent way to do this is, like @Isaac, to treat the universe as behavior all the way down, never bottoming out at some thing it's the behavior of. Which is why you might be right, @Count Timothy von Icarus, that this falls into the tradition of process philosophy.

It makes it hard, if not impossible, to find a counterexample in the functionalist approach's own terms. Which means the only way around that is a table flip - reframe the discussion. — fdrake

Exactly. Functionalism, the universal solvent. You and @Isaac and I had exactly this discussion I think ― in a thread about gender, was it?

So, yes, to understand this thread, the first thing is to understand that there will never be anything anyone can come up with that will force the functionalist to say "I can't model that." Never anything that has to be acknowledged as substance rather than behavior.

But precisely because there can, in some very real sense, be no counterargument to functionalism, no counterexample, there ought to be a niggling doubt, such as I have nursed for a long time. Ralph and Sam, striding through philosophy with their functionalist hammers for years, and one day Ralph says, "Hey Sam. You ever notice that the world is full of nails? That there's nothing but nails? That's funny, isn't it?"

That's the sentiment behind this thread. -

J

2.4kThe deflationist stops at the schema structure, it's a barrier to all further inquiry. — fdrake

J

2.4kThe deflationist stops at the schema structure, it's a barrier to all further inquiry. — fdrake

Got it, thanks. And I would say that the ban on connections between being and thought goes in both directions, so to speak. A deflationist won't entertain any modeling between thought, in general, and concept -- indeed, that wouldn't even be considered modeling -- and will likely also reject any talk about my thoughts or consciousness, since reference to such arcana aren't necessary to behavioral modeling, on this view.

So, yes, to understand this thread, the first thing is to understand that there will never be anything anyone can come up with that will force the functionalist to say "I can't model that." Never anything that has to be acknowledged as substance rather than behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

I think this is substantially right, but pressing the functionalist on what they mean by modeling can be useful, along the lines of @fdrake's "weak correspondence." The problem may be as much with the whole modeling project as with a functionalist approach to metaphysics. -

fdrake

7.2ksince reference to such arcana aren't necessary to behavioral modeling, on this view. — J

fdrake

7.2ksince reference to such arcana aren't necessary to behavioral modeling, on this view. — J

Yeah. There's relevant questions about what counts as a behaviour, in what contexts. I enjoy that degree of recursion in a functionalist approach, but I don't know if that move would be available to our deflationist stereotypes. There's probably some logical workaround to it that lets you construe such questions as a modelling in the sense I put it, but I don't know how to do it without reducing the concept to be just our behaviour. Which isn't quite the same thing. We'd be talking about how we talk about stuff, rather than about stuff. Even if the stuff we're talking about is how we talk about stuff. -

fdrake

7.2kAnd sortals were my logico-linguistic way of getting at — Srap Tasmaner

fdrake

7.2kAnd sortals were my logico-linguistic way of getting at — Srap Tasmaner

Yeah, I remember. Sortals are a good touchstone. I'd prefer to leave them to the side in my own posts for now, even though they're under the surface as the "essence" {ooh-err} as the counts-as relation. -

frank

18.9kBut precisely because there can, in some very real sense, be no counterargument to functionalism, no counterexample, there ought to be a niggling doubt, such as I have nursed for a long time. Ralph and Sam, striding through philosophy with their functionalist hammers for years, and one day Ralph says, "Hey Sam. You ever notice that the world is full of nails? That there's nothing but nails? That's funny, isn't it?" — Srap Tasmaner

frank

18.9kBut precisely because there can, in some very real sense, be no counterargument to functionalism, no counterexample, there ought to be a niggling doubt, such as I have nursed for a long time. Ralph and Sam, striding through philosophy with their functionalist hammers for years, and one day Ralph says, "Hey Sam. You ever notice that the world is full of nails? That there's nothing but nails? That's funny, isn't it?" — Srap Tasmaner

Say the scientist is talking about convergent evolution where mammals and fish have evolved the same phenotype in response the same conditions (like dolphins and sharks). She needs to be able to easily distinguish mammals from fish in some way other than behavior. The easiest way to distinguish them would be by genetic lineage, which is already handled in the scientific names for the animals. This is not a counter argument. It's just an example of why we don't generally categorize animals by behavior. -

schopenhauer1

11kAnd that's why I'm posting. Much as I've enjoyed building models over the years, I'm a little uncomfortable that the approach I'm describing has a sort of blindness. Whenever a question is raised about what something is, it is immediately rewritten as a question about how that thing behaves, so that we can get started modelling that bundle of behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

schopenhauer1

11kAnd that's why I'm posting. Much as I've enjoyed building models over the years, I'm a little uncomfortable that the approach I'm describing has a sort of blindness. Whenever a question is raised about what something is, it is immediately rewritten as a question about how that thing behaves, so that we can get started modelling that bundle of behavior. — Srap Tasmaner

This is basically the argument I have been making regarding Philosophy of Mind for years. Others on here have similarly pointed out this "blind spot"- it's the Hard Problem. It's metaphysics par excellence. Talks of maps overtake talks of terrain. The terrain is discarded as "non-sense" and thus "cannot be spoken". The continentals don't seem to care about this self-imposed rule. It tends to lead to neologisms, mystical flights of fancy, solipsism, and all the other epithets that more analytic-types would throw at it. -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k

LLM's become even more complex too, because if one believes that the words it uses to make sentences refer to things, then naturally some can believe this indicates such things have some kind of "inner mental life".

But yeah, in this case statistical correlation makes sense. I'd wager it's different with biological systems, like ducks or tigers or foxes. -

Mapping the Medium

366But yeah, in this case statistical correlation makes sense. I'd wager it's different with biological systems, like ducks or tigers or foxes. — Manuel

Mapping the Medium

366But yeah, in this case statistical correlation makes sense. I'd wager it's different with biological systems, like ducks or tigers or foxes. — Manuel

And people. ... Exactly. ... LLMs concretize abstractions haphazardly, like many people often do, but people are in real life situations, where metaphor, analogy, and body language are understood culturally, not statistically. ... LLMs are a 'reflection' of society in a given snapshot, but they do not operate at all like the continuum a biological being exists in. -

Leontiskos

5.6kAlso nothing more than a quick intervention...

Leontiskos

5.6kAlso nothing more than a quick intervention...

Oh yeah, really far. Most ordinary people aren't going to notice that the only consistent way to do this is, like Isaac, to treat the universe as behavior all the way down, never bottoming out at some thing it's the behavior of. Which is why you might be right, @Count Timothy von Icarus, that this falls into the tradition of process philosophy. — Srap Tasmaner

Supposing we want to play the game of finding the "next of kin" to the OP, I would look to metaphysical or mereological bundle theory, not process philosophy. Process thought does provide an alternative to substance metaphysics, but it is historically and metaphysically thick in a way that the modeling approach is not, and I don't think it has received much attention in the Anglophone world apart from religious philosophers.

When I studied metaphysics we focused on Aristotelian-Thomistic metaphysics, and the competition was bundle theory, not process philosophy. The main ideas are often traced to Hume, and permeate the Anglophone horizon. The OP strikes me as some variety of bundle theory. See:

A second important issue in contemporary discussions of substance is whether substances are in some sense reducible to their properties, or whether there exists some further component, such as Locke’s notion of a substratum discussed in section 2.5. Both views have been defended in recent discussions. — Bundle theories versus substrata and “thin particulars” | SEP

For another entry from SEP, see <the subsection on objects>.

-

In speaking to Parmenides and Heraclitus Aristotle says something like this, "You fellows have theories that possess admirable simplicity and unification, but they turn out to be too simple to save the appearances. What we find in nature is motion, and this entails both perdurance and change."

Our age has this same tendency towards simplicity and unification, whether in the form of determinism, string theory, monism, or bundle theory. The question is whether the notion of a bundle or the notion of behavior is sufficient to save the appearances that we actually encounter in reality. Aristotle says that it is not sufficient, and that substance/substratum is also necessary. The idea is that, contrary to "behaviorism," nouns are not dispensable.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Why is public nudity such a taboo behavior, not only in the religious community but society as well?

- Doesn't the concept of 'toxic masculinity' have clear parallels in women's behavior?

- The behavior of anti-religious posters

- Most human behavior/interaction is choreographed

- Are there any limits to human behavior, outside natural laws?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum