-

Wayfarer

26.1k(From time to time, I'll criticize posts on the basis of what I see as their 'positivist' philosophical attitude. I don't generally agree with positivism in philosophy, but it isn't necessarily a pejorative, and is still very much an active influence in philosophy and culture. This article compiled from the various sources listed below tries to spell out what positivism is, how it originated, and its ongoing influence.)

Wayfarer

26.1k(From time to time, I'll criticize posts on the basis of what I see as their 'positivist' philosophical attitude. I don't generally agree with positivism in philosophy, but it isn't necessarily a pejorative, and is still very much an active influence in philosophy and culture. This article compiled from the various sources listed below tries to spell out what positivism is, how it originated, and its ongoing influence.)

Definition: Positivism (philosophy) a philosophical system recognizing only that which can be scientifically verified or which is capable of logical or mathematical proof, and therefore rejecting metaphysics and theism.

Origins of Positivism in Auguste Comte's 'Three Stages'

The term 'positivism' originated with Auguste Comte (19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857). Comte was a French philosopher, mathematician and writer, often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense of the term. Comte's ideas were also fundamental to the development of sociology, with him inventing the term and treating the discipline as the crowning achievement of the sciences.

Comte was a voluminous writer, but the specific aspect that is relevant to this topic is his 'three stages' theory of social development. This posits that human knowledge and social evolution tends to progress through three distinct intellectual phases: the theological, the metaphysical, and the positive (or scientific) stage. In the initial, theological stage, phenomena are explained by appealing to supernatural beings or divine powers, whether through animism, polytheism, or monotheism. This stage is characterized by a reliance on faith and imagination. The second, transitional metaphysical stage replaces supernatural explanations with abstract forces, essences, or philosophical concepts, such as "nature" or "cause," to understand the world. While moving away from direct divine intervention, it still lacks empirical verification. Finally, the positive or scientific stage represents the pinnacle of intellectual development, where understanding is based on empirical observation, experimentation, and the discovery of verifiable, scientific laws. In this ultimate stage, humanity abandons the search for absolute causes and instead focuses on observable facts and the relationships between them. Comte believed this progression mirrored both the development of the individual mind from childhood to maturity and the historical evolution of human society, with sociology itself emerging as the highest and most complex science in the positive era.

Neo-positivism

While Comte's form of positivism was very influential during the 19th Century it faded from prominence after WWI. However the 20th c saw the emergence of neo-positivism, a movement prominently centred around the Vienna Circle in the early 20th century. This was a philosophical movement that sought to establish a rigorous, scientifically grounded philosophy by emphasizing empirical verification and logical analysis of language. Key figures like Rudolf Carnap were central to its development.

Unlike earlier forms of positivism, neo-positivism, often called logical positivism or logical empiricism, focused less on societal stages and more on the meaningfulness of statements and the structure of scientific knowledge. Its core tenets included:

Unity of Science: Neo-positivists believed that all genuine scientific knowledge, whether from the natural or social sciences, could ultimately be expressed in a single, unified language (often envisioned as the language of physics) and that there were no fundamental methodological differences between scientific disciplines.

Emphasis on Logic and Language: They held that many philosophical problems were, in fact, "pseudo-problems" arising from the misuse or ambiguity of language. Thus, logical analysis of scientific language became paramount, aiming for precision and clarity in formulating theories and propositions. Carnap, in particular, stressed the need for constructing formal, logical systems to analyze scientific discourse.

Empiricism: While building on earlier empiricist traditions, neo-positivism insisted on public, experimental verification or confirmation as the basis of knowledge, moving beyond purely personal experience.

The Vienna Circle, comprising philosophers, scientists, and mathematicians like Moritz Schlick, Otto Neurath, and Kurt Gödel, codified these ideas in their 1929 manifesto, Scientific Conception of the World: The Vienna Circle. Despite its eventual dispersal due to the rise of Nazism, neo-positivism profoundly influenced 20th-century analytic philosophy and the philosophy of science, pushing for clarity, empirical rigor, and an anti-metaphysical stance in intellectual inquiry.

Meanwhile, A.J. Ayer's Language, Truth and Logic, published in Britian 1936, served as a concise and highly influential English-language manifesto for logical positivism. While he acknowledged some modifications to the views of the Vienna Circle, Ayer's book presented their core tenets with clarity and directness, making it accessible to a wider audience and significantly impacting British philosophy.

Its main arguments revolved around the Verification Principle, which asserted that a statement is cognitively meaningful only if it is either an analytic truth (true by definition, such as mathematical or logical statements) or if it is empirically verifiable (i.e., observations could, in principle, confirm or refute it). This principle led to the sweeping dismissal of traditional metaphysics, theology, and much of ethics as "literally meaningless" – not false, but rather devoid of factual content because they could not be subjected to empirical testing.

Criticism and Decline

A basic criticism of positivism, particularly logical positivism and its central Verification Principle, is that the principle itself fails to meet its own criterion for meaningfulness.

The Verification Principle states that a proposition is cognitively meaningful only if it is either an analytic truth (true by definition, like "All bachelors are unmarried") or empirically verifiable (its truth or falsity can be, in principle, determined by observation).

Critics, most famously Karl Popper, argued that the Verification Principle itself is neither an analytic truth nor empirically verifiable.

It is not an analytic truth: The principle is not true merely by definition. It makes a substantive claim about what constitutes "meaning."

It is not empirically verifiable: One cannot perform an experiment or make an observation to verify the claim that "all meaningful statements are empirically verifiable or analytic." The principle cannot be "seen" or "tested" in the way a scientific hypothesis can.

Therefore, according to its own rigorous standards, the Verification Principle is rendered meaningless. This self-referential paradox became a devastating blow to logical positivism. If the very foundation of their theory of meaning was itself meaningless, then the entire edifice it sought to build, including its rejection of metaphysics and other areas of philosophy, was undermined.

This critique, along with other problems such as the difficulty in conclusively verifying universal scientific laws (e.g., "All swans are white" cannot be verified by observing every swan, but only confirmed), ultimately led to the decline of logical positivism as a dominant philosophical movement. Karl Popper, in response, proposed falsifiability as a criterion for demarcating science from non-science, arguing that a scientific theory is one that can be falsified by empirical evidence, rather than one that can be verified.

Ongoing Influence

While formal logical positivism, with its strict adherence to the Verification Principle, largely receded in philosophical circles due to its inherent contradictions, the underlying "positivist attitude" or spirit remains a powerful and pervasive current in modern culture, particularly in scientific research, policy-making, and everyday discourse.

Here's how that enduring influence manifests:

1. Emphasis on Empirical Evidence and Data: The core positivist insistence that knowledge must be grounded in observable facts and empirical data is the bedrock of modern science. Researchers across all disciplines – from medicine and physics to economics and social sciences – are expected to provide empirical evidence to support their claims. The reliance on quantitative data, statistical analysis, and controlled experiments to establish truth is a direct legacy of positivism.

2. Scientism (or the "Science as Ultimate Authority" View): There's a widespread cultural belief that science is the ultimate arbiter of truth and that scientific methods are the most reliable path to knowledge. When facing a complex problem, the common instinct is to "look at the science" or consult experts who employ scientific methodologies. This deference to scientific authority, sometimes bordering on an almost religious faith in its infallibility, is a strong echo of positivism's elevation of the positive stage.

4. Rejection of Metaphysics and Unverifiable Claims: In popular discourse, there's a general skepticism towards claims that cannot be empirically tested or are seen as purely speculative. Discussions about spirituality, values, or abstract philosophical concepts often struggle to gain traction in mainstream conversations unless they can somehow be "proven" or shown to have tangible effects. This resonates with the positivist dismissal of metaphysics as meaningless.

5. Focus on Objectivity and Value-Neutrality (even if contested): While critical theorists and postmodernists have extensively critiqued the notion of complete objectivity and value-neutrality, the ideal of dispassionate, objective inquiry still underpins much scientific and academic practice. Researchers strive to minimize bias and present findings "as they are," reflecting a positivist aspiration for knowledge untainted by subjective influence.

6. Technological Advancement: The relentless pursuit of technological innovation is deeply tied to the positivist worldview. It's about understanding the natural world through empirical means to predict, control, and manipulate it for practical ends. From AI development to climate modeling, the drive for measurable progress through scientific application is evident.

But it's also important to point out 'post-positivism' which acknowledges that certainty is rarely achieveable but often probabilistic and provisional; that theories are not simply verified so much as confirmed or falsified; and which also recognises that values and paradigms inevitably shape theoretical posits.

Sources and References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auguste_Comte

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Positivism

https://meridianuniversity.edu/content/how-positivism-shaped-our-understanding-of-reality -

T Clark

16.1k

T Clark

16.1k

A good and thorough OP. Interesting and well written. You clearly put a lot of work into this.

A statement is meaningful only if it is empirically verifiable (i.e., its truth or falsity can be determined by observation or experience) or if it is an analytic truth (true by definition, like mathematical or logical statements). This principle led to the rejection of traditional metaphysics, ethics, and theology as "meaningless" in a cognitive sense, not false, but rather propositions that couldn't be tested. — Wayfarer

The irony is that this explanation for the rejection of metaphysics is itself metaphysics. I guess that’s just another way of saying “the principle itself fails to meet its own criterion for meaningfulness.” -

Wayfarer

26.1kThanks. In positivism’s heyday, this wasn’t obvious. I did a unit on Language Truth and Logic as an undergrad, that and B F Skinner’s Beyond Freedom and Dignity were the two books I loved to hate. (Passed the unit, though.)

Wayfarer

26.1kThanks. In positivism’s heyday, this wasn’t obvious. I did a unit on Language Truth and Logic as an undergrad, that and B F Skinner’s Beyond Freedom and Dignity were the two books I loved to hate. (Passed the unit, though.)

i’ve often mentioned that a lecturer I had in philosophy, David Stove - incidentally not the one who gave the LTL course - used to compare positivism to the mythological uroboros, the snake that swallows its own tail. That was based on the closing words of Hume’s Treatise - ‘take any book of scholastic metaphysics….’. Stove pointed out that the same criticism applied to Hume’s text. Hume wrote his Treatise as a critique of previous philosophy, but at the same time, his book was also presented as philosophy. ‘The hardest part’, Stove would say, with a mischievous grin, ‘is the last bite.’

Something I noticed reading the material on Comte was this:

the positive or scientific stage represents the pinnacle of intellectual development, where understanding is based on empirical observation, experimentation, and the discovery of verifiable, scientific laws. In this ultimate stage, humanity abandons the search for absolute causes and instead focuses on observable facts and the relationships between them. — Wayfarer

‘Abandons the search for absolute causes’ is a pregnant phrase. By this, I’m sure Comte was referring to the final causes in scholastic-Aristotelian philosophy, the reason that things exist or happen to be. This rejection of final causation is the beginning of the so-called ‘instrumental reason’ that is characteristic of Enlightenment and post-enlightenment philosophy. I recall an exchange in a televised debate between Richard Dawkins and a Catholic Bishop, who was posing the ‘but why are we here?’ question. Dawkins replied ‘Why we exist, you're playing with the word "why" there. Science is working on the problem of the antecedent factors that lead to our existence. Now, "why" in any further sense than that, why in the sense of purpose is, in my opinion, not a meaningful question.’ Had I been in the audience, I would have stirred the pot by asking ‘why?’ - but I wasn’t and the debate moved on. -

J

2.4kThank you, very good article. I hope we can use it as a touchstone on TPF to ground discussions of positivistic metaphysics, as it's very fair. Looking at the six "enduring influences," at least two -- #1 and #5 -- seem like a good thing to me, on balance. That is, more likely to do good than harm, in their normal uses. My main gripe, personally, is with scientism. I love science, and hate to see it misunderstood in the way that scientism does.

J

2.4kThank you, very good article. I hope we can use it as a touchstone on TPF to ground discussions of positivistic metaphysics, as it's very fair. Looking at the six "enduring influences," at least two -- #1 and #5 -- seem like a good thing to me, on balance. That is, more likely to do good than harm, in their normal uses. My main gripe, personally, is with scientism. I love science, and hate to see it misunderstood in the way that scientism does. -

Fire Ologist

1.7kInteresting and thoughtfully expounded. This big picture view is where I like to live. And you seem to be sitting near me, here in the clouds, where we can move between the fog and the clear view of everything.

Fire Ologist

1.7kInteresting and thoughtfully expounded. This big picture view is where I like to live. And you seem to be sitting near me, here in the clouds, where we can move between the fog and the clear view of everything.

Finally, the positive or scientific stage represents the pinnacle — Wayfarer

Did you ever notice how people with new ideas usually think they’ve discovered the last, pinnacle stage of human development? Not only is that unlikely, but I often find that, like an adolescent who discovers angst, although their discovery is a first for them in their experience, there have been others seeing what they see before them. We all think we live on the cutting edge of what there is to know. But wasn’t Sextus Empiricus a physician, up to his elbows in blood and the empiracal? How different was his worldview, or Hume’s, than Compte’s?

the rejection of traditional metaphysics, ethics, and theology as "meaningless" in a cognitive sense, not false, but rather propositions that couldn't be tested. — Wayfarer

The “you aren’t asking the right question” response to a question.

a single, unified language (often envisioned as the language of physics) and that there were no fundamental methodological differences between… — Wayfarer

Truth is one. I like it, but positivists probably shouldn’t opine about such observations…

many philosophical problems were, in fact, "pseudo-problems" arising from the misuse or ambiguity of language — Wayfarer

It’s an important observation, to keep us honest. But there is no therapy to soothe a desire to know - only knowledge. We might not find there are any answers for us, but science will never address “why?” And there is no proving the negative statement: “there is no answer, so there was no question.” That’s like telling me I’m not actually hungry so I don’t need food, when I am hungry.

pushing for clarity, empirical rigor, — Wayfarer

That is the wisdom of positivism. It’s the right attitude.

It’s Aristotle’s attitude towards Plato. And Descartes attitude (clear and distinct, developer of mathematical certainty). And Locke’s attitude towards Descartes…. And in a different manner but similar spirit, Nietzsche’s attitude towards any who think they know something (science, but gay science, but science nonetheless…)

a proposition is cognitively meaningful only if it is either an analytic truth (true by definition, like "All bachelors are unmarried") or empirically verifiable (its truth or falsity can be, in principle, determined by observation). — Wayfarer

That all seems similar to Hume, which supports my comments above.

Verification Principle itself is neither an analytic truth nor empirically verifiable. — Wayfarer

Isn’t this criticism, which is a correct one I believe, a similar criticism as lodged against views such as “there is no truth” and “all is relative”? The critique is that these views are self-defeating. Which seems correct. A priori correct. Everything there is, for the knowing mind, can’t be reduced to the physical/empirical, while that mind is doing the reduction.

Seems obvious to me: ‘seeming to me’ will never be ‘seeing’ photons of light.

falsifiability as a criterion for demarcating science from non-science — Wayfarer

That is important. Few things I’d ask the positivist about this though: is it only physics that grounds all falsifiability? Or is there any science/knowledge that might need some other ground to be falsified? Couldn’t the person or scientist himself or herself be a ground, something knowable but not strictly physical? We simply are self-reflective things. Couldn’t something exist in the reflection that can’t be found in the thing reflected? I’m not talking “soul” or spirit, just, not physical, so we can save science. There is physics, and there is also the scientist to draw from, the physics of the experiments and the something else of the physicist who is doing physics. (Like mind-body, but that is just one classification of the substance(s).)

the underlying "positivist attitude" or spirit remains a powerful and pervasive current in modern culture, particularly in scientific research, policy-making, and everyday discourse. — Wayfarer

I don’t have a quarrel with the attitude. Particularly when doing science qua science. I just think metaphysics is science, and its laboratory is the mind itself.

We don’t get to address “why” or “who” by saying “why” can’t be weighed and measured as part of a brain, so “who cares anyway?”. There is much still there to be addressed.

deference to scientific authority, sometimes bordering on an almost religious faith in its infallibility — Wayfarer

Right. Positivists (and all of us) need to recall the total annihilation of knowledge that was Nietzsche, before we pick up the hammer and tuning fork again to do our experiments. Science that replaces God as absolute authority, can become just another face for the same God, the judge of all truth and creator of all there is to be called true.

Discussions about spirituality, values, or abstract philosophical concepts often struggle to gain traction in mainstream conversations unless they can somehow be "proven" or shown to have tangible effects. — Wayfarer

Yes. All of the best discussions - love, good, faith - reduced basically to one subject, namely, physics.

Researchers strive to minimize bias and present findings "as they are," reflecting a positivist aspiration for knowledge untainted by subjective influence. — Wayfarer

Totally un-self-aware, the aspirations of non-bias and openness to hypotheses, can be rigidly and narrowly constrained by the bias of scientism.

the drive for measurable progress through scientific application is evident. — Wayfarer

Positivism has dispensed with the vantage point that would allow one to measure “progress”. Are people any less likely to murder, steal, lie and center the universe around themselves? What will a faster internet or longer lasting lightbulb do to foster any progress on those fronts? Scientific progress may only move us sideways, allowing us to do what we always did and value what we always valued, in a new way. No true “progress” in thousands of years. Positivism doesn’t ask that question (a sociology that seeks only the chemical and behavioral and functional explanations, ignores the immaterial spirit that only arrives in the truly social, the communion of minds around meaning and shared understandings. Positivists just won’t go there, as they sit in the middle of it.).

As with many philosophical movements, there is much to digest and learn from them, and incorporate into one’s understanding. But also, much left wanting, yet to be clarified and discovered.

What if some things can only be expressed by looking around the words, and not at them? The positivist has to say, such things don’t exist.

Maybe. Maybe not. No reason to conclude anything.

In my view, I agree with the scientist/positivist to the extent we are talking about physics, and would never seek to refute or contradict positive, proven science. If there is reason, and I think there is, there is the reasonable, and science/logic/math is best to demonstrate that. I just see, with so many questions remaining, there is no necessity to judge which questions can be answered and which should not be asked - we don’t know what we don’t know. -

ssu

9.8kEven if no questions in the OP, a good synopsis of positivism! :cheer:

ssu

9.8kEven if no questions in the OP, a good synopsis of positivism! :cheer:

I think the real problem with positivism isn't at the philosophical ideology itself, but simply adapting it's methods in a very poor manner. I will here comment on positivism from the viewpoint of sciences, not philosophy. Starting from the idea that sciences are universal, there is then often this attempt then to create a mathematical theory of something, something like physics. If it's mathematical, it's scientific! And if we have statistics, then it is easy to make in the end some kind of function. And when you talk about mathematical functions, many commentators that don't know much about mathematics drop out. Yet especially in social sciences you have to have a clear understanding of what those statistics actually tell, how are they linked to each other.

I myself studied economic history. I remember once a professor gave us an example of how bad positivism can be in history. He read us out loud a page of a study, which was terribly boring and confusing, just basically a list of various sources and original documents. There wasn't any attempt to make a summary, to make it to a cohesive description of the events. This was basically just the "documents themselves telling history".

Another example was someone making VERY long statistical research paper trying to measure the prosperity of Finland for the last 1000 years: from the year 1000 to the year 2000. I remember the dead silence in the room from economic historians, until someone remarked how little do we know about the year 1000, about the pre-Sweden era when Finns were majority pagan and about the difficulties of measuring anything from that society to our modern one. The moderator quickly went diplomatically onward and introduced the next research. But I guess the attitude that you could measure prosperity of a people that at start weren't a unified people but largely pagan tribes and then compare that prosperity to the 19th and 20th Centuries with mathematical precision is something that someone with a firm belief in positivism belief would do.

Hence when I think of the two examples, they don't actually criticize positivism itself, it's just that a lot of bad research can be made with positivism. But I guess even worse research can be made by other philosophical ideologies. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Even though Positivism & Empiricism, postulated as-if universal principles, fail their own test, they still serve as good rules of thumb for Scientific investigations into the material world. But, when Philosophical theories & principles are judged by that pragmatic criteria, they miss the the point of philosophizing : to go beyond the limits of the senses using Logical inference, not mechanical magnification. :smile:A basic criticism of positivism, particularly logical positivism and its central Verification Principle, is that the principle itself fails to meet its own criterion for meaningfulness. — Wayfarer

The Point of Process Philosophy :

I can't say with any authority, what Whitehead's "point" was. But my takeaway is that he was inspired by the counterintuitive-yet-provable "facts" of the New Physics of the 20th century ─ that contrasted with 17th century Classical Physics ─ to return the distracted philosophical focus :

a> from what is observed (matter), to the observer (mind), b> from local to universal, c> from mechanical steps to ultimate goals.

Where Science studies percepts (specifics ; local ; particles), the New Philosophy will investigate concepts (generals ; universals ; processes). The "point" of that re-directed attention was the same as always though : basic understanding of Nature, Reality, Knowledge, and Value.

https://bothandblog8.enformationism.info/page44.html -

Apustimelogist

946But it's also important to point out 'post-positivism' which acknowledges that certainty is rarely achieveable but often probabilistic and provisional; that theories are not simply verified so much as confirmed or falsified; and which also recognises that values and paradigms inevitably shape theoretical posits. — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946But it's also important to point out 'post-positivism' which acknowledges that certainty is rarely achieveable but often probabilistic and provisional; that theories are not simply verified so much as confirmed or falsified; and which also recognises that values and paradigms inevitably shape theoretical posits. — Wayfarer

The irony is that I would consider myself closer to these post-positivists than positivists, and many post-positivists would probably also disagree with your ideas.

Asking for someone to clarify what they mean doesn't make them a positivist. -

T Clark

16.1k‘Abandons the search for absolute causes’ is a pregnant phrase. By this, I’m sure Comte was referring to the final causes in scholastic-Aristotelian philosophy, the reason that things exist or happen to be. This rejection of final causation is the beginning of the so-called ‘instrumental reason’ that is characteristic of Enlightenment and post-enlightenment philosophy. — Wayfarer

T Clark

16.1k‘Abandons the search for absolute causes’ is a pregnant phrase. By this, I’m sure Comte was referring to the final causes in scholastic-Aristotelian philosophy, the reason that things exist or happen to be. This rejection of final causation is the beginning of the so-called ‘instrumental reason’ that is characteristic of Enlightenment and post-enlightenment philosophy. — Wayfarer

I certainly am not a positivist, but I also don't have much use final causes. That's not because they're wrong. It's just that they are not particularly useful - philosophically, socially, scientifically, practically, or personally. [insert T Clark schpiel on metaphysics here]. I think this is representative of why, in our discussions of this kind of issue, you and I sometimes agree and sometimes look down our noses at each other. -

Hanover

15.2kI'd suggest, from what you've written, that positivism does not fail under the Popper revision of falsifiability you've described.

Hanover

15.2kI'd suggest, from what you've written, that positivism does not fail under the Popper revision of falsifiability you've described.

In other words, I followed positivism's failure to prove itself positively and affirmatively which was its internal definitional self destruction, but if you alter that to require that you must show where positivism fails to offer acceptable answers to our problems, then it is sustainable under Popper's revision, if the proper evidence can be shown.

What this means to me is that positivism's failure must be tied to its utilitarian failure to yield useful results as opoosed to just a devestating internal logical inconsistency in its basis.

That is, if you can show how psychological or economic models (for example) fail to offer consistently, predictable results, then that counts for me as a substantive blow against positivism as opposed to just an analytic attack on the self consistency of the theory. -

Leontiskos

5.6kI'd suggest, from what you've written, that positivism does not fail under the Popper revision of falsifiability you've described. — Hanover

Leontiskos

5.6kI'd suggest, from what you've written, that positivism does not fail under the Popper revision of falsifiability you've described. — Hanover

So you are claiming that under Popper's thesis "that a scientific theory is one that can be falsified by empirical evidence," Logical Positivism and its Verification Principle meet the criteria required to be counted as a scientific theory? How so? How is the Verification Principle able to be falsified by empirical evidence?

-

An interesting and useful thread, . :up: -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kThere is a pretty massive conflation common in this area of thought re "science" and "empiricism." This is pivotal in how different varieties of empiricism often justify themselves. They present themselves as responsible for the scientific and technological revolution that led to the "Great Divergence" between Asia and Europe in the 19th century, and this allows for claims to the effect that a rejection of "empiricism" is a rejection of science and technology, or, in some versions, that empiricism is destined to triumph through a sort of process of natural selection, since it will empower its users through greater technological and economic advances.

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kThere is a pretty massive conflation common in this area of thought re "science" and "empiricism." This is pivotal in how different varieties of empiricism often justify themselves. They present themselves as responsible for the scientific and technological revolution that led to the "Great Divergence" between Asia and Europe in the 19th century, and this allows for claims to the effect that a rejection of "empiricism" is a rejection of science and technology, or, in some versions, that empiricism is destined to triumph through a sort of process of natural selection, since it will empower its users through greater technological and economic advances.

But this narrative equivocates on two different usages of "empiricism," one extremely broad, the other extremely narrow. In the broad usage, empiricism covers any philosophy making use of "experience" and any philosophy that suggests the benefits of experimentation and the scientific method. By this definition though, even the backwards Scholastics were "empiricists." Hell, one even sees Aristotle claimed as an empiricist in this sense, or even claims that Plotinus was an empiricist because his thought deals with experience. By contrast, the narrow usage tends to mean something more like positivism, particularly its later evolutions.

I have written about this before, but suffice to say, I think empirical evidence for this connection is actually quite weak. As I wrote earlier:

However, historically, the "new Baconian science," the new mechanistic view of nature, and nominalism pre-date the "Great Divergence" in technological and economic development between the West and India and China by centuries. If the "new science," mechanistic view, and nominalism led to the explosion in technological and economic development, it didn't do it quickly. The supposed effect spread quite rapidly when it finally showed up, but this was long after the initial cause that is asserted to explain it.

Nor was there a similar "great divergence," in technological progress between areas dominated by rationalism as opposed to empiricism within the West itself. Nor does it seem that refusing to embrace the empiricist tradition's epistemology and (anti)metaphysics has stopped people from becoming influential scientific figures or inventors. I do think there is obviously some sort of connection between the "new science" and the methods used for technological development, but I don't think it's nearly as straightforward as the empiricist version of their own "Whig history" likes to think.

In particular, I think one could argue that technology progressed in spite of (and was hampered by) materialism. Some of the paradigm shifting insights of information theory and complexity studies didn't require digital computers to come about, rather they had been precluded (held up) by the dominant metaphysics (and indeed the people who kicked off these revolutions faced a lot of persecution for this reason).

By its own standards, if empiricism wants to justify itself, it should do so through something like a peer reviewed study showing that holding to logical positivism, eliminativism, or some similar view, tends to make people more successful scientists or inventors. The tradition should remain skeptical of its own "scientific merits" until this evidence is produced, right? :joke:

I suppose it doesn't much matter because it seems like the endgame of the empiricist tradition has bifurcated into two main streams. One denies that much of anything can be known, or that knowledge in anything like the traditional sense even exists (and yet it holds on to the epistemic assumptions that lead to this conclusion!) and the other embraces behaviorism/eliminativism, a sort of extreme commitment to materialist scientism, that tends towards a sort of anti-philosophy where philosophies are themselves just information patterns undergoing natural selection. The latter tends to collapse into the former due to extreme nominalism though.

I suppose I should qualify that though in that there seems to be a third, "common sense" approach that brackets out any systematic thinking and focuses on particular areas of philosophy, particularly in the sciences, and a lot of interesting work is done here. -

Hanover

15.2kyou are claiming that under Popper's thesis "that a scientific theory is one that can be falsified by empirical evidence," Logical Positivism and its Verification Principle meet the criteria required to be counted as a scientific theory? How so? How is the Verification Principle able to be falsified by empirical evidence? — Leontiskos

Hanover

15.2kyou are claiming that under Popper's thesis "that a scientific theory is one that can be falsified by empirical evidence," Logical Positivism and its Verification Principle meet the criteria required to be counted as a scientific theory? How so? How is the Verification Principle able to be falsified by empirical evidence? — Leontiskos

I wasn't arguing that Positivism meets the claim of a scientific theory in fact. I was saying it could in theory. This is a distinction between necessity and contingency.

The argument of the OP was that Positivism fails by necessity. It holds that it must be proved valid by empirical means to be sustained, and since it's lacking, it must fail.

My position is that Pooper's revision allows Positivism to be sustained until falsified, meaning it will survive contingent upon there being no facts falsifying it.

What makes it fail, as I alluded to, might be the lack of predictive value in such things as economic and psychological theories. That is the blow to Positivism I'd think meaningful, less so internal inconsistencies in its logic. That is, the proof is in the pudding of how it works. -

Leontiskos

5.6kMy position is that Pooper's (!) revision allows Positivism to be sustained until falsified, meaning it will survive contingent upon there being no facts falsifying it. — Hanover

Leontiskos

5.6kMy position is that Pooper's (!) revision allows Positivism to be sustained until falsified, meaning it will survive contingent upon there being no facts falsifying it. — Hanover

So Popper talks about what "can be falsified," which is a possibility claim. It is a claim about falsifiability. Given that anything at all can be "sustained until falsified," it would follow that anything at all fulfills Popper's claim, construed in that way, which in turn would make that claim vacuous. Popper is asking whether it is able to be falsified, not whether it has been falsified. I think @Janus was struggling with this same distinction recently.

Note too that if something is not falsifiable then it obviously won't ever be falsified and this is another reason why the "has been falsified" consideration is not helpful. In that sense checking whether something has been falsified is precisely beside the point for Popper. If it has been falsified, then for Popper it is a scientific theory. In that case it passes his test of falsifiability. Popper's targets are those theories which have not been falsified and can never be falsified (because they are unfalsifiable).

(It is interesting to ask whether Popper's work remains within or moves beyond Positivism. I suspect that @Wayfarer might say that Popper's response is a kind of extension of Positivism.)

What makes it fail, as I alluded to, might be the lack of predictive value in such things as economic and psychological theories. That is the blow to Positivism I'd think meaningful, less so internal inconsistencies in its logic. That is, the proof is in the pudding of how it works. — Hanover

That looks like a pragmatic consideration, which is rather different than Popper's consideration. Popper's notion of falsifiability is separate from a notion of whether "it works." Non-empirical theories might work very well, depending on one's aim. The Logical Positivists would do well to reflect on how well their non-empirical theory succeeded in achieving their aims, and what those aims really were.

(Revised to clean up the argument.) -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

That is, if you can show how psychological or economic models (for example) fail to offer consistently, predictable results, then that counts for me as a substantive blow against positivism as opposed to just an analytic attack on the self consistency of the theory.

It seems to me that this would still be consistent with opposing philosophies though, since many of them hardly deny the techniques in question or their potential predictive power. For example, a Neo-Scholastic like C.S. Peirce is hardly denying the usefulness of predictive models and experimentation, he is just asserting a robust metaphysical realism that supposedly augments, makes sense of, and improves this.

The broadly positivist position would be better justified by somehow showing that explorations of metaphysics, or causes in the classical sense, tend to retard scientific, technological, and economic progress, or at least that they add nothing to them. I think this will tend to be difficult though, as a lot of more theoretical work (which tends to be paradigm defining and influential) is also the place where that sort of thing often plays a large role.

Of course, the positivist can also claim that such explorations are only useful because of defective quirks in human psychology. However, this seems like a thesis that it would be extremely hard to justify empirically, although certainly you can "fit the evidence to it." But that's true of a lot of things. -

Leontiskos

5.6k- It's pretty interesting to ask about the relation between Positivism and Pragmatism. They seem to be cousins, and at least some pragmatists are positivists who jumped ship when it began to sink.

Leontiskos

5.6k- It's pretty interesting to ask about the relation between Positivism and Pragmatism. They seem to be cousins, and at least some pragmatists are positivists who jumped ship when it began to sink. -

Wayfarer

26.1kEverything there is, for the knowing mind, can’t be reduced to the physical/empirical, while that mind is doing the reduction. — Fire Ologist

Wayfarer

26.1kEverything there is, for the knowing mind, can’t be reduced to the physical/empirical, while that mind is doing the reduction. — Fire Ologist

That same mind which is bracketed out of early modern science with the division of the primary and secondary attributes - primary being those precisely measurable and quantifiable, secondary being color, taste, smell, and those other attributes which rely on subjective apprehension. Within that milieu, physics becomes paradigmatic, because of its precision and its universality. The laws of motion, for example, are thought to be universal in scope (which they are, subject to the limitations later discovered by relativity.)

The upshot of which is that the mind then has to be re-introduced to the world from which it has been banished, as a consequence or result of these same ‘universal’ physical forces which finds its most consistent expression in so called ‘eliminative materialism’. A hard problem, indeed.

Starting from the idea that sciences are universal, there is then often this attempt then to create a mathematical theory of something, something like physics. If it's mathematical, it's scientific! — ssu

Pretty much as I said above. It is, to allude to a rather controversial, but also profound, book, ‘the Reign of Quantity’. One of the discussions that prompted this thread, was about how qualia (an item of academic jargon in philosophy of mind referring to the qualities of subjective experience) can be explained away as illusion.

I also don't have much use final causes. — T Clark

From my readings on it, final causality was a fatal flaw in Aristotelian physics, as it in effect attributes intentionality to inanimate objects (i.e. a stone’s ‘natural place’ is on the Earth.) But it’s very different in biology, where indeed there’s a pretty strong ‘neo-Aristotelian’ revival nowadays. After dispensing with ‘teleology’, biologists found in necessary to re-introduce ‘teleonomy’ referring to the apparent goal-directedness of organisms ( wiki). It’s been said that Aristotle’s biology anticipated the discovery of DNA, not because he had any idea of molecular biology, but because he had worked out what is necessary for the transmission of traits.

Besides final causality is routinely invoked in day-to-day life. ‘Why is the kettle boiling?’ can be answered with either ‘because the water has reached boiling point’ or ‘I want to make tea’. Both are course correct but they answer slightly different questions.

Seems to me your proposing a kind of pragmatic redefinition of positivism, suggesting that its value lies in yielding useful or predictive models. But but that wasn't the central concern of logical positivism, which were epistemic and semantic—concerned with the meaning and justifiability of statements. Popper’s falsifiability criticism was a critique of the verification principle. While pragmatic utility is important in science, it doesn’t rescue the philosophical framework of positivism from its internal and methodological issues. I can see circumstances where a positivist attitude is pragmatically useful. But that isn't the point at issue.

There is a pretty massive conflation common in this area of thought re "science" and "empiricism. — Count Timothy von Icarus

It's not that difficult: empirical data is what can be captured by the senses (or instruments). Basically, what is tangible, physical, 'out there somewhere'.

(It is interesting to ask whether Popper's work remains within or moves beyond Positivism. I suspect that Wayfarer might say that Popper's response is a kind of extension of Positivism.) — Leontiskos

I don't think so. Recall that the initial targets of Popper's critique were psychoanalysis and marxist economics. Both of these were held up as being scientific theories. Popper pointed out that they were so poorly defined that they could accomodate any kind of observation - they couldn't be falsified. He contrasted that with Einstein's theory of relativity, which was subject of empiricial confirmation (or disconfirmation) which came from Eddington's observation of the gravitational deflection of starlight in 1919.

Besides, Popper, later in life, developed his 'third worlds' ontology which I think would be very different from anything the positivsts would endorse. In The Self and Its Brain, co-authored with John Eccles, he explicitly defends a form of interactionist dualism, rejecting the reduction of mind to brain — a clear departure from physicalist or positivist assumptions.

Even though Positivism & Empiricism, postulated as-if universal principles, fail their own test, they still serve as good rules of thumb for Scientific investigations into the material world. — Gnomon

Of course. It's when they're applied to 'the problems of philosophy' that tend towards 'scientism' - as you say. -

Fire Ologist

1.7kthe mind then has to be re-introduced to the world from which it has been banished, — Wayfarer

Fire Ologist

1.7kthe mind then has to be re-introduced to the world from which it has been banished, — Wayfarer

:up:

…banished by the same mind, that now has to do the reintroduction. -

Wayfarer

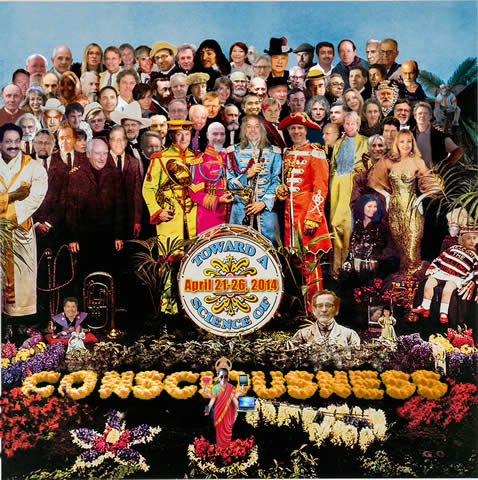

26.1kWell, the times surely are a'changing. Something a lot of people don't appreciate, is that around the time David Chalmer's published his famous Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness, he was a a keynote speaker at the initial Science of Consciousness conference in Arizona (convened by Stuart Hameroff.) The TSC conferences are widely regarded as a landmark event, bringing together scientists and philosophers from various disciplines to discuss consciousness in a serious academic setting. This undoubtedly contributed to big changes in the field.

Wayfarer

26.1kWell, the times surely are a'changing. Something a lot of people don't appreciate, is that around the time David Chalmer's published his famous Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness, he was a a keynote speaker at the initial Science of Consciousness conference in Arizona (convened by Stuart Hameroff.) The TSC conferences are widely regarded as a landmark event, bringing together scientists and philosophers from various disciplines to discuss consciousness in a serious academic setting. This undoubtedly contributed to big changes in the field.

Herewith the image from the 2014 (20th Anniversary) conference, with everyone in the picture being some philosopher of mind or consciousness.

Deepak Chopra cheek-in-jowl with Daniel Dennett. Who'd have thought? -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Right, but that's precisely where the conflation can occur. Are things (e.g. cats, trees, clouds, etc.) "in the senses" or are they "projected onto the senses," or "downstream abstractions?" Empiricism has tended to deny the quiddity of things as "unobservable," but a critic might reply that nothing seems more observable than that when one walks through a forest they sees trees and squirrels and not patches of sense data. Indeed, experiencing "patches of sense data without quiddity," is what people report during strokes, after brain damage, or under the influence of high doses of disassociate anesthetics—that is, the experience of the impaired and not the healthy.

But this is obviously going to trickle down across the sciences. Is zoology the study of discrete organic wholes and their natural kinds of is it the study of relatively arbitrary fuzzy "systems?" The entire organization of the special sciences seems to rely on allowing something of quiddities to play a role in defining them. The denial of quiddities plays a pretty large role in a number of classic empiricist arguments that lead to indeterminacy as well.

If empiricism refers just to experience, it starts to cover essentially all philosophy, whereas if it refers to some narrowed down "sense experience" there are still difficulties disambiguating this. The wider definitions of "sense experience" open the door to a very large number of thinkers outside the empirical tradition. Hence, I would say that the "method" has to be expanded to excluding specific sorts of judgements, experiences, and intuitions, which tends to mean supposing some metaphysics to justify such an exclusion.

This sort of goes with Hegel's quip that: "gossip is abstract, my philosophy is not." To already assume that the higher level and intelligible is "more abstract" is to have made a very consequential metaphysical judgement.

Yes, but sadly they became Pragmatists and not Pragmaticists :cool: -

Wayfarer

26.1kAre things (e.g. cats, trees, clouds, etc.) "in the senses" or are they "projected onto the senses," or "downstream abstractions?" Empiricism has tended to deny the quiddity of things as "unobservable," but a critic might reply that nothing seems more observable than that when one walks through a forest they sees trees and squirrels and not patches of sense data. Indeed, experiencing "patches of sense data without quiddity," — Count Timothy von Icarus

Wayfarer

26.1kAre things (e.g. cats, trees, clouds, etc.) "in the senses" or are they "projected onto the senses," or "downstream abstractions?" Empiricism has tended to deny the quiddity of things as "unobservable," but a critic might reply that nothing seems more observable than that when one walks through a forest they sees trees and squirrels and not patches of sense data. Indeed, experiencing "patches of sense data without quiddity," — Count Timothy von Icarus

All due respect, I think you’re complicating the picture a little. John Locke, who was the emblematic British empiricist, was of the view that the mind is a blank slate, tabula rasa, on which impressions are made by objects. The term ‘quiddity’ is from scholastic philosophy, is precisely the kind of thing that Locke wouldn’t appeal to. He is associated with representative realism, whereby images represent objects, and general ideas are abstracted from the perception of many similar objects. J S Mill took a similar view.

RevealI’ve quoted this many times before, Jacques Maritain’s criticism of empiricism in The Cultural Impact of Empiricism:

For empiricism there is no essential difference between the intellect and the senses. The fact which obliges a correct theory of knowledge to recognize this essential difference is simply disregarded. What fact? The fact that the human intellect grasps, first in a most indeterminate manner, then more and more distinctly, certain sets of intelligible features -- that is, natures, say, the human nature -- which exist in the real as identical with individuals, with Peter or John for instance, but which are universal in the mind and presented to it as universal objects, positively one (within the mind) and common to an infinity of singular things (in the real).

Thanks to the association of particular images and recollections, a dog reacts in a similar manner to the similar particular impressions his eyes or his nose receive from this thing we call a piece of sugar or this thing we call an intruder; he does not know what is sugar or what is intruder. He plays, he lives in his affective and motor functions, or rather he is put into motion by the similarities which exist between things of the same kind; he does not see the similarity, the common features as such. What is lacking is the flash of intelligibility; he has no ear for the intelligible meaning. He has not the idea or the concept of the thing he knows, that is, from which he receives sensory impressions; his knowledge remains immersed in the subjectivity of his own feelings -- only in man, with the universal idea, does knowledge achieve objectivity. And his field of knowledge is strictly limited: only the universal idea sets free -- in man -- the potential infinity of knowledge.

Such are the basic facts which Empiricism ignores, and in the disregard of which it undertakes to philosophize. The logical implications are: first, a nominalistic theory of ideas, destructive of what ideas are in reality; and second, a sensualist notion of intelligence, destructive of the essential activity of intelligence. In the Empiricist view, intelligence does not see, for only the object or content seen in knowledge is the sense object. In the Empiricist view, intelligence does not see in its ideative function -- there are not, drawn form the senses through the activity of the intellect itself, supra-singular or supra-sensual, universal intelligible natures seen by the intellect in and through the concepts it engenders by illuminating images. Intelligence does not see in its function of judgment -- there are not intuitively grasped, universal intelligible principles (say, the principle of identity, or the principle of causality) in which the necessary connection between two concepts is immediately seen by the intellect. Intelligence does not see in its reasoning function -- there is in the reasoning no transfer of light or intuition, no essentially supra-sensual logical operation which causes the intellect to see the truth of the conclusion by virtue of what is seen in the premises. Everything boils down, in the operations, or rather in the passive mechanisms of intelligence, to a blind concatenation, sorting and refinement of the images, associated representations, habit-produced expectations which are at play in sense-knowledge, under the guidance of affective or practical values and interests. No wonder that in the Empiricist vocabulary, such words as 'evidence', 'the human understanding', 'the human mind', 'reason', 'thought', 'truth', etc., which one cannot help using, have reached a state of meaningless vagueness and confusion that makes philosophers use them as if by virtue of some unphilosophical concession to the common human language, and with a hidden feeling of guilt. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

John Locke, who was the emblematic British empiricist, was of the view that the mind is a blank slate, tabula rasa, on which impressions are made by objects.

Right, but it was Aristotle who first wrote in De Anima:

Haven't we already disposed of the difficulty about interaction involving a common element, when we said that mind is in a sense potentially whatever is thinkable, though actually it is nothing until it has thought? What it thinks must be in it just as characters may be said to be on a writing tablet on which as yet nothing stands written: this is exactly what happens with mind.

And the Peripatetic Axiom is "there is nothing in the intellect that was not first in the senses." Likewise, with representationalism, there is first the adage that "whatever is received is received in the mode of the receiver."

I don't mean to complicate things, just to point out that the very broad definition of "empiricism" (often employed by empiricists themselves in arguments meant to justify empiricism) lets in a great deal of non-empiricist philosophy. Locke is a fine example. He actually has a quite particular anthropology and view of how perception and reason must work that is essential to why he is considered properly an "empiricist." He ends up with problems (if you consider them such) like the circularity between real and nominal essences because of these assumptions.

I bring it up because I used to think: "who possibly couldn't be an empiricist?" But as your quote describes quite well, there is more to it than simply a philosophy that involves the senses, experience, and experimentation. What will constitute valid "experience" is itself defined by a prior anthropology and metaphysics.

With positivism, I find a similar problem. It's often framed that rejecting positivism is rejecting observation-based modeling, etc. But really, what tends to differentiate positivism is not accepting such things, but rather refusing to accept anything else.

I guess my poon -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

:rofl:

I was going to say, "I guess my point (not poon) is that the "empirical" part of positivism has a sort of fuzzy definition that can be used, intentionally or not, to smuggle in a lot of assumptions. -

Punshhh

3.6kForgive me, I have a satirical bent. I would engage more, but I don’t have the breadth of reading in philosophy, or in Western philosophy. I come from the perspective of eastern philosophy, or Theosophy.

Punshhh

3.6kForgive me, I have a satirical bent. I would engage more, but I don’t have the breadth of reading in philosophy, or in Western philosophy. I come from the perspective of eastern philosophy, or Theosophy.

For me empiricism includes the contents of mind, so is regarded as universal. I don’t have the divide between idealism and positivism(I’m not sure if this is even the right word) and find it a means, or excuse, for argument, rather than anything else. -

Wayfarer

26.1k

Wayfarer

26.1k

we said that mind is in a sense potentially whatever is thinkable, though actually it is nothing until it has thought? What it thinks must be in it just as characters may be said to be on a writing tablet on which as yet nothing stands written: this is exactly what happens with mind.

That’s a philosophically pregnant phrase if ever there was one. I’m fascinated by that idea. -

ssu

9.8kPretty much as I said above. It is, to allude to a rather controversial, but also profound, book, ‘the Reign of Quantity’. One of the discussions that prompted this thread, was about how qualia (an item of academic jargon in philosophy of mind referring to the qualities of subjective experience) can be explained away as illusion. — Wayfarer

ssu

9.8kPretty much as I said above. It is, to allude to a rather controversial, but also profound, book, ‘the Reign of Quantity’. One of the discussions that prompted this thread, was about how qualia (an item of academic jargon in philosophy of mind referring to the qualities of subjective experience) can be explained away as illusion. — Wayfarer

Positivism put's objectivity on a pedestal.

To emphasize objectivity is totally rational and sound: you find subjectivity in the creation stories of various religions. Why did something happen? How was the Earth formed? Where did we come? It was Gods will. There isn't an explanation for the answer, it's an issue of faith, an issue that religiouns are quite open about. In Christianity Jesus talks about opening your heart to him to find God, not to "use your brain and think it through". Positivism, a product of the 19th Century, had still to confront religious thinking in the way that there wasn't in the 20th Century or today, even if the real fight betwen science and religion had happened in the Renaissance in Europe. (In Muslim countries, religion prevailed and there was no Renaissance)

Explaining qualia away as illusion is one example. The emphasis on objectivity puts everything that is subjective to be unimportant, or simply not something of a scientific matter. Yet I think the problem is far larger than this. Objectivity has logical rules which simply limit just what can be accurately modeled.

Here is the problem: many of our most important and critical questions about reality cannot be modeled accurately with a totally objective model, because objectivity demands an external viewpoint of the issues at hand. Yet we ourselves are part of the universe and when this fact needs to be in the model, then we cannot make an accurate model. We cannot just assume an external viewpoint, somebody observing reality / the universe outside it.

The most obvious example is in physics when a measurement itself affects the object that is measured. This isn't a trivial problem that you can just assume away in physics. It's the reason just why we have the elaborate models of Quantum Physics. In Quantum Physics we simply just cannot assume that the subatomic particles behave as Newtonian physics says. Yet this problem at all limited to physics.

Usually in all models, be the in economics or sociology or whatever, where we find this dilemma of a Black Box, where something crucial happens in a Black Box through it we have the outcome, but we cannot model just what happens in the Black Box, we typically have this problem of subjectivity. So it's no wonder that for example when thinking about how we actually learn and think something is this confusing Black Box.

Computer science shows the problem in the most simple and clearest way. As computers follow algorithms, they cannot follow an instruction "Do something else". That's not an algorithm: an exact list of instructions that conduct specified actions done step by step. In fact, a computer can follow this only if it has as in instruction, "If asked do something else, then x". Why can them humans answer this? Because they can understand what they have done (hence in a way they are aware of the algorithms they use) and then do something they have not done. But this is a subjective decision and subjectivity comes into the model. And now the objective modelling has a huge problem: it cannot model just what happened, how the human did the something else. In order for there to be objectivity, there has to be a meta-algorithm that the human follows, but that cannot be listed.

This isn't just a philosophical problem, this is basically a mathematical problem. Yet people don't realize how big this is because we are lacking the mathematical axiom behind this. -

Wayfarer

26.1kObjectivity has logical rules which simply limit just what can be accurately modeled.

Wayfarer

26.1kObjectivity has logical rules which simply limit just what can be accurately modeled.

Here is the problem: many of our most important and critical questions about reality cannot be modeled accurately with a totally objective model, because objectivity demands an external viewpoint of the issues at hand. Yet we ourselves are part of the universe and when this fact needs to be in the model, then we cannot make an accurate model. We cannot just assume an external viewpoint, somebody observing reality / the universe outside it. — ssu

Completely agree! I think the ‘meta-algorithm’ you refer to might be close to what Roger Penrose was getting at in his Emperor’s New Mind. But overall in agreement with your post. -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k

Great post Wayf. I may be nerding out again, but I think there's a very interesting argument to be made against positivism, that is in my opinion devastating for positivism, which is Michael Polanyi's argument on tacit knowledge.

Granted, he's not super well-known in philosophy, sadly, but his arguments I think are more convincing than ever Popper's.

Just my brief two cents. :up:

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum