Comments

-

Web development in 2023Thanks FJ, so far there is no project but it’s good to know there are people here to help :up:

-

Web development in 2023

Gmail slack Trello Netflix and grammarly — flannel jesus

I was just thinking about the sites and applications I use, and thought of some more: Rome2Rio, Google Maps, Airbnb (edit: just to be clear, I mean the browser applications/websites, not the phone apps). -

Web development in 2023

https://mail.google.com/

SPAs still use changing URLs, which in this context are called routes, corresponding to route handlers in the JavaScript. The page itself is not loaded. -

Web development in 2023:up: Yep, I was just describing an aspect of SPAs as commonly conceived. I said "often", probably going for "hitherto".

-

Web development in 2023I abhorred these things when they first came out. If your internet is not good or perhaps is throttled due to reaching an allotted usage level, nothing would ever load and worse never told you it didn't. They seemed to have improved it by forcing a manual redirect/better fail-safes in more robust frameworks but there was nothing like clicking a link or performing an action and the browser itself telling you "hey it failed" right when it did so you knew to refresh or try again later. Just my 2 cents. — Outlander

Yep, although as you say, frameworks are dealing with that now, but I think it still partly depends on the willingness of developers to provide for it, as with accessibility more generally. -

Web development in 2023From my experience, I have seen python being used as a server-side language only relatively recently (but perhaps I just haven’t been around the right groups of people who love Python). Originally, people (as far as I know) used Java, C#, and PHP. If someone was running a website, it was most likely PHP or Java (and not Python). If python was used for web servers before PHP/Java (like Django) in a stable fashion, then I am simply unaware of it and will have to read up on that. — Bob Ross

Just to set the record straight...

There were three things you said or implied that I took objection to: (1) that Python is a new language or at least a new language for web development, (2) that Python and/or Python frameworks have not been properly tested and are unstable or insecure, and (3) that PHP belongs in the same language ballpark as Java.

What I did not claim is that Python was used in web development before PHP was; as far as I know the Django guys were the first to use it to build websites. But twenty years (since Django was released) is a decent length of time, and its record is very good. And yes, PHP has always been more popular as a way of building websites.

Regarding (3), you could just as easily classify things like this: Java and Python are general purpose languages that can do anything, and on the other side you have PHP and JavaScript, which are just scripting languages. (But I'm not making value judgements here, just illustrating different ways of looking at it)

I will have to checkout Django sometime though. Is it minimalistic or bloated? — Bob Ross

It's a difficult question to answer without knowing what you mean, but depending on which way you look at it, it's both. Flask, on the other hand, is certainly minimalist. But Django adheres strongly to conventions and paradigms, such as DRY, and the separation of concerns of MVC (although they use different nomenclature and slightly different structure, namely model-view-template), so it's a good coding experience. Things never got messy for me in Django, as they definitely did when I was building in JavaScript frameworks.

But since you don't like Python, there's little point in wasting your time on it. And PHP these days seems to be significantly faster than Python (that's what they say at least, though whether this results in faster websites and web applications is another matter). So I say, enjoy your PHP :cool: -

Web development in 2023NodeBB was originally built with MongoDB, but it runs on Postgres just fine. That's what I deployed it on. I think that compatibility was added sometime in v2. — Leontiskos

Great, I didn't realize.

The simple answer is that I wanted pagination, even prescinding from its SEO favorability. Infinite scroll on a long-form philosophy forum didn't seem right to me. NodeBB offers both, and individual users can even change the setting on the client side. So I'm not a great person to ask about Discourse, as I never installed it. I have it on good authority that it is a bit harder to install and consumes more resources, but those aren't deal breakers. Both platforms are robust, with more to offer than Plush. Granted, I have come to appreciate the simplicity and distraction-less nature of Plush. — Leontiskos

Aside from wanting to control the data and code, I'd actually be perfectly satisfied with the way Plush works with just a few changes, like better tools for moderation, "zen mode" post composing, Markdown support, dark mode, and ignore lists. (I know that for dark mode I could just use Stylebot as you suggest, but this is about built-in functionality; as admin I need to see what most people see).

I had that idea until I installed Misago and started digging into the Github history. There are many more features than I had anticipated, especially when it comes to security, moderation, IP tracking, etc.—but I think ChatGPT has already given you a good sense of what is involved. — Leontiskos

I know what you mean. At first when you think of how to build a forum it seems easy, but there's a lot more to it.

Also, after I joined I realized more concretely that TPF has one thing no other philosophy forum has, and that no forum software can create: a healthy community of users. Without that, it's all just window dressing. — Leontiskos

This is what makes a decision to move to another platform a big and difficult one. Incidentally, it always sounds odd to me when I see people saying that discussion forums are dead (because Reddit, social media, and Discord). I guess my experience is not normal.

Whatever you decide, I think a forum software would benefit from having a philosophical client. The things you guys have suggested and requested from Plush seem spot-on, and are much more thoughtful than the short-sighted requests I have seen from the business world. — Leontiskos

:up:

Although the Plush folks assure me that PlushForums will be maintained for the foreseeable future, they don't seem very interested in adding new features, perhaps because they've been putting most of their efforts into their new platform https://insta.forum/ (totally moving away from long-form, so not suitable for us). -

Web development in 2023I know there are some things that don't have associated text box button icons, like sup for superscript.

-

Web development in 2023Would I be correct in saying that Plush only supports a sub-set of BBCode, i.e. not all the tags are implemented (e.g. tables)? — Wayfarer

I don't know. Last I checked, Plush documentation was virtually non-existent. You must be right though. -

Web development in 2023Firstly, there is no "the best" framework or languages for programming: it depends entirely on what the project is that one is developing. — Bob Ross

I agree. In my original post I was examining what I see as two competing paradigms of web development today, but it's no doubt true that solutions lie in between.

newer languages (like Python with python flask) — Bob Ross

they are slower and tend to have been been pentested — Bob Ross

are the fad — Bob Ross

Flask is older than Laravel, and Python is older than PHP. Python's most popular framework, Django, was released in 2003, before all the PHP frameworks that are still going (I think, pretty much). Django and Python have a very strong reputation for security; PHP does not (an unfortunate legacy of wilder times, no doubt, which the language has put behind it). Generally, your Python/Javascript vs. PHP/Java dualism doesn't reflect history or reality very well.

If you love PHP, cool, I have nothing against it (except bad experiences and personal taste). I'm not interested in cheerleading for anything or in anyone else's cheerleading–but let's get the facts straight.

My philosophical approach to web projects is minimalism (viz., keep it simple stupid), compartmentalization (viz., always, always, always separate code so that it is modularized: cleaner, more scalable, easier to read, and takes up less storage), documentation (viz., always document what the heck this thing does, and pick languages and frameworks that are well-supported: easier to get people to work on the project, easier to teach them, and easier on you to develop with it), and secure (viz., don't pick the newest language, framework, or library on the block, it takes time for ethical hackers to find vulnerabilities); so I love minimalistic MVC (model-view-controller) frameworks with amazing documentation that utilize very well-known and well-established server-side languages, such as Laravel. — Bob Ross

I won't argue with any of that.

With regards to libraries and frameworks like React and Angular, it is important to know that it all runs client-side, which adds runtime on the user's browser. Although it is beneficial to run some stuff on the client-side, to save server-side runtime, it is important not to over-bloat the client side; which I worry happens with those kinds of libraries and frameworks for a lot of projects who picked them just because they are in style right now. I would rather keep it simple, and use pre-compiled TypeScript for client-side operations, and keep it absolutely minimal to save client-side runtime. — Bob Ross

Yes, and from a development perspective the front end frameworks can be so bloated, it takes discipline and coordination to keep things under control. But when the aim is a speedy responsive user experience, and given that browsers are powerful enough for the job, SPAs can be a good choice. But I see where you're coming from and as I said in the OP, I believe it's becoming possible now to achieve the superior user experience from within server frameworks like Laravel and Django, but without adding a whole Javascript framework to the mix.

So despite your odd view of Python, we kind of agree.

If you are trying to revamp this website, then please do not hesitate to contact me if you need any help; as I would not mind helping out with a site like this that I enjoy using. — Bob Ross

Thanks Bob.

What are you guys currently using for the client-side, server-side, query, and style-sheet languages? — Bob Ross

As mentioned in the OP and the ensuing discussion, I'm not hosting TPF myself and I don't have any control of the code. It's hosted by PlushForums, built on Vanilla, which you'll be happy to know is written in PHP :grin: -

Web development in 2023Its use of indentation for syntax seems like a monumentally bad idea. What do you have to say for that? — SophistiCat

I think it’s great. Most code is indented anyway, even when what you actually need is curly braces. Python enforces it so it’s all you need, and readability is then assured—and improved, in my opinion. It’s never been an issue. I’ve hardly ever had problems with it when working with other people’s code, for example. Occasionally you get an ‘IndentationError’ but it’s no big deal.

And are there advantages to Python beyond its use in server scripting? — SophistiCat

I’ve only used it for web development, associated modules, and scripting, but it’s a true general purpose language and designed as such. It’s used to build many kinds of applications, for machine learning, data science, etc. Whether there are advantages beyond the obvious ease of use, flexibility, and readability, I don’t know. I don’t claim it could replace all the Java in the world. I like the way it looks and it’s a lot of fun to use. -

Web development in 2023That would definitely be a meaty project, but rewarding if it could be done. Misago is the Python frontrunner, which is why it was my first choice. Unfortunately it is provided by a single developer who works on it in his spare time, but he is talented and I am sure he would appreciate help (see <this post> regarding the current plans for Misago). NodeBB and Discourse have multiple full-time developers along with the attached commercial interests, and therefore possess more stability. I agree regarding Vanilla and PHP. — Leontiskos

It’s unfortunate that Misago isn’t more active. As things stand, I suppose it would have to be NodeBB or Discourse. I’ll install them both and try them out. I tried Discourse a while ago and quite liked it, but I didn’t pursue it. The big headache in either case will be migrating the data. My familiarity is with relational databases so I’d probably be more at home with Discourse, which uses PostgreSQL. What is certain is that neither has a big button that says “Migrate from PlushForums”.

A crucial factor in my considerations was long form vs short form discussion formats, as a philosophy forum requires a more long form format. A lot of the newer, asynchronous forum frameworks cater to short form discussion and phones/tablets (Discourse does not even support pagination). They are becoming a blend of forums and instant messaging, running away from phpBB in a way that strikes me as both good and bad. If the architecture is suitable one could restyle them for long form purposes, but I am not great with CSS so I wanted something compatible with long form discussion right out of the box. Plush is good on this score, and Misago looks and feels a lot like Plush. — Leontiskos

I’m curious: what is it about, say, Discourse, that steers things away from long-form discussion? From what I could tell when I tried it, navigating a discussion was easier than on other platforms, and it made composing long posts much more pleasurable than here (same with NodeBB: full-screen distraction-free editing, for example). Maybe I’m missing the obvious, but pagination isn’t a requirement for long-form is it? Although it occurs to me that pagination is better for SEO.

Thanks for your thoughts. I didn't know you were a developer. I don't think I could call myself a developer at this point, although I could get back into it fairly easily. — Leontiskos

I’m really just going by intuition and doing my usual contrarian thing. Sometimes it leads me in good directions. I haven’t really been a developer for years, since I was a bit stuck in maintenance with the last project I was involved with. But yeh, I’m getting back into it nicely. -

Web development in 2023I just realized it might be assuming I had no experience in web development, so I asked for a new estimate to take into account my experience:

Taking these adjustments into account, the comprehensive project duration might come down to roughly 25-50 weeks (6-12 months) if undertaken full-time. -

Web development in 2023Answers from ChatGPT 4 based on working on it full-time:

Building a forum with a feature set similar to Discourse from scratch, especially when learning React and Next.js concurrently, is a substantial endeavor. Here's a broad estimation of the time it might take based on various stages of development:

1. **Learning Basics (React and Next.js)**:

- **Duration**: 2-4 weeks.

- This phase includes understanding the fundamental concepts, building small projects, and becoming comfortable with the development environment.

2. **Design and Architecture Planning**:

- **Duration**: 1-3 weeks.

- Outline the features you want to implement. Decide on database structures, authentication mechanisms, state management strategies, and other foundational elements.

3. **Core Features (MVP - Minimum Viable Product)**:

- **Threads and Posts**: 2-3 weeks.

- **User Registration & Authentication**: 2 weeks.

- **User Profiles**: 1 week.

- **Basic Admin Tools (user management, basic moderation)**: 2-3 weeks.

- **Duration**: 7-9 weeks for a basic MVP.

4. **Advanced Features**:

- **Advanced Moderation Tools (post edits history, user warnings)**: 2 weeks.

- **Private Messaging**: 2-3 weeks.

- **Search Functionality**: 2 weeks.

- **Categories & Tags**: 2 weeks.

- **Notifications**: 2 weeks.

- **Duration**: 8-11 weeks.

5. **Additional Features (Common in Discourse and Similar Platforms)**:

- **Badges & User Levels**: 2 weeks.

- **Bookmarks**: 1 week.

- **Polls**: 1-2 weeks.

- **Attachments & Media Handling**: 2 weeks.

- **Duration**: 6-8 weeks.

6. **Testing, Bug Fixing, and Refinement**:

- **Duration**: 4-8 weeks.

- This is crucial. As you develop, you'll discover edge cases, usability issues, and bugs that need addressing.

7. **Data Migration and Integration**:

- **Duration**: 2-4 weeks.

- Migrating from an existing platform can present challenges, especially if the data structures differ.

8. **Deployment and Scaling**:

- **Duration**: 2-4 weeks.

- This phase includes setting up servers, handling security considerations, ensuring the platform scales with user growth, and other deployment-related tasks.

Given these broad estimations, you're looking at approximately **32-61 weeks (8-15 months)** to develop a full-fledged forum application with a feature set akin to Discourse. This time frame assumes you're working on it full-time. If it's a side project, the duration will extend accordingly.

It's crucial to note that these estimates are quite generic and can vary based on individual speed, unforeseen challenges, feature complexities, and other factors. Some developers might move faster, while others might need more time, especially when dealing with the intricacies of a forum application.

Then I said what about security:

Absolutely, security is paramount when developing any web application, especially something as user-focused as a discussion forum. Neglecting security can lead to data breaches, unauthorized access, and many other serious issues. Let's break down the key security considerations and their potential time implications:

1. **Authentication**:

- Implementing secure login mechanisms is essential. Consider using established libraries or services like OAuth or Auth0.

- **Duration**: 1-2 weeks (on top of basic user registration & authentication).

2. **Authorization**:

- Ensure that users can only perform actions they're permitted to do (e.g., only admins can delete any post).

- **Duration**: 1-2 weeks.

3. **Data Validation and Sanitization**:

- Protect against SQL injections, script injections, etc. by validating and sanitizing user input.

- **Duration**: 2-3 weeks.

4. **Secure Data Transmission**:

- Implement HTTPS across your forum to encrypt data in transit.

- **Duration**: Less than a week (but requires ongoing monitoring).

5. **Data Encryption**:

- Passwords and sensitive data should be encrypted before being stored.

- **Duration**: 1 week.

6. **Session Management**:

- Implement secure session handling to prevent session hijacking or fixation.

- **Duration**: 1-2 weeks.

7. **Rate Limiting**:

- Implement rate limiting to prevent abuse (e.g., rapid-fire login attempts or spammy post creation).

- **Duration**: 1 week.

8. **Content Security Policy (CSP)**:

- Define what resources can be loaded to protect against cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks.

- **Duration**: 1 week.

9. **Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) Protection**:

- Protect your forum from CSRF attacks by implementing anti-CSRF tokens.

- **Duration**: 1 week.

10. **Regular Security Audits & Updates**:

- Tools like Dependabot can be used to stay updated with the latest security patches for your dependencies.

- **Duration**: Ongoing, but setting up monitoring and automated updates might take a day or two.

11. **Backup and Recovery**:

- Regularly back up the forum data and have a recovery plan in place for emergencies.

- **Duration**: 1-2 weeks.

Adding up these security-specific durations, you're looking at an additional **12-19 weeks** dedicated solely to security. These estimates are, again, very broad. Some tasks may take less time if you're using specific frameworks or libraries that handle them out-of-the-box. However, security is not a one-time task. It requires ongoing attention, regular updates, and occasional audits to ensure that the platform remains secure as threats evolve.

Incorporating these security considerations into the earlier timeline, you're looking at a more comprehensive project duration of approximately **44-80 weeks (11-20 months)** if undertaken full-time.

(Come on Plush, give us Markdown support please. EDIT: Plush just confirmed to me that they will only ever support BBCode, not Markdown :angry: ) -

Web development in 2023

Good article. As I say, I do find the arguments convincing now. But I don’t think it’s essentially about which technologies you’re using, but rather the nature of the thing you’re building. Anyway, it’s not a huge deal for me, although I don’t know if I’ll ever get over my disgust at looking at all those long strings of atomic classes.

This is a pretty balanced article. -

Web development in 2023Note that the question I asked ChatGPT was how long it would take to build a general purpose platform, not specifically for one group of users, so I think that's significant.

-

Web development in 2023I've recently been using Laravel with Inertia, React, and Tailwind for the frontend. Works really well. — Michael

Cool. I used to be dead against non-semantic CSS like Tailwind, but the arguments in its favour are persuasive. I think it depends what you're building. If it's content-focused, semantic makes sense, but if it's highly interactive, things like Tailwind look good.

I've been building a few things with NextJS for practice. I guess that fits in the stack roughly where Inertia does for you (I'd never heard of Intertia). Although--devil's advocate--don't you think the architecture is questionable when you're using not only two but three frameworks? (I'm not counting Tailwind since most projects use a CSS framework anyway)

I used to think that. I always thought that HTML should just be done in HTML, not JavaScript. But then I actually tried React and Vue and quite like it. — Michael

Yeh, I've been enjoying the JavaScript frameworks too, but I continue to question them.

That strikes me as an overestimate. I've built business CRMs used by a FTSE 100 company in a few months. — Michael

Not everyone can be as awesome as you. :wink: -

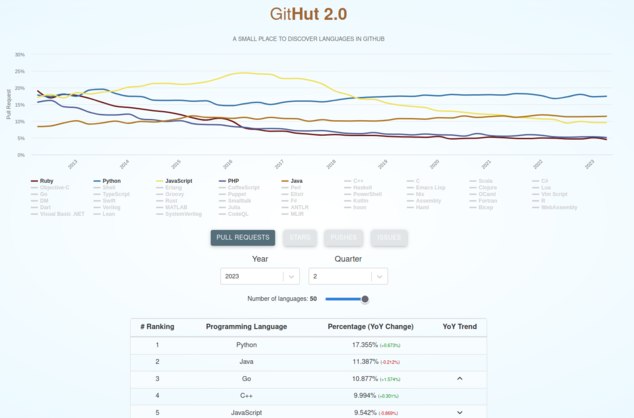

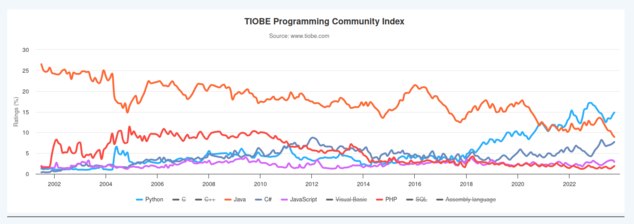

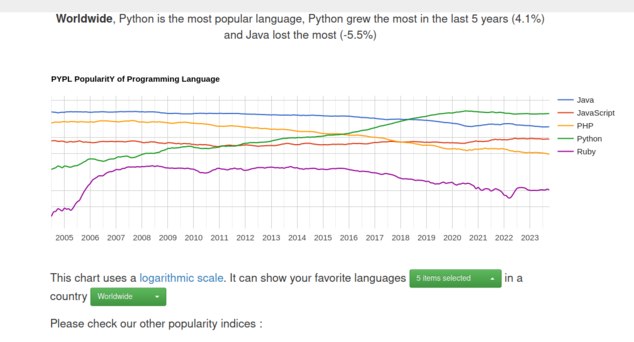

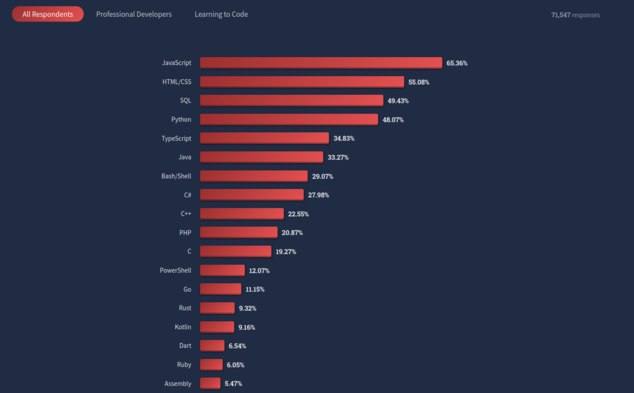

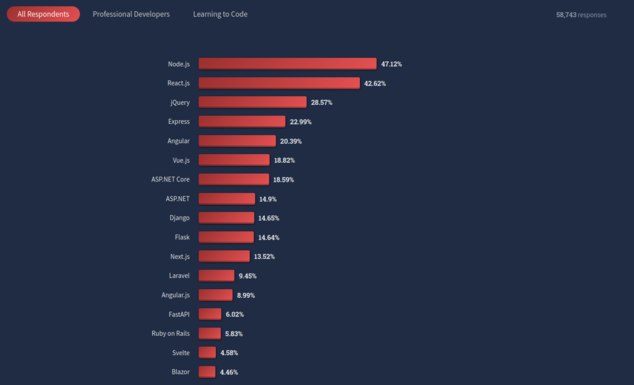

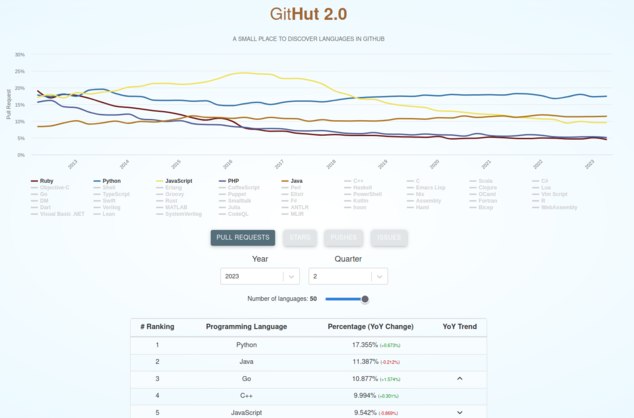

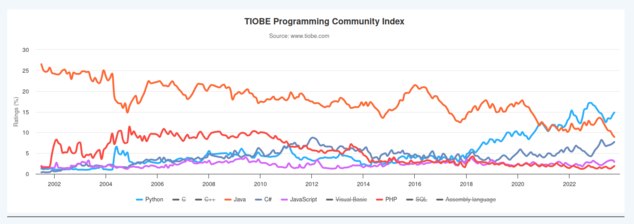

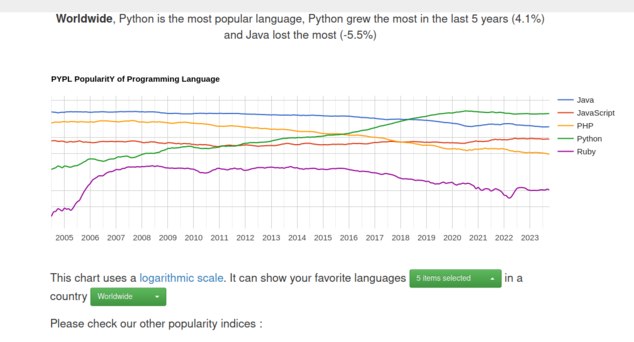

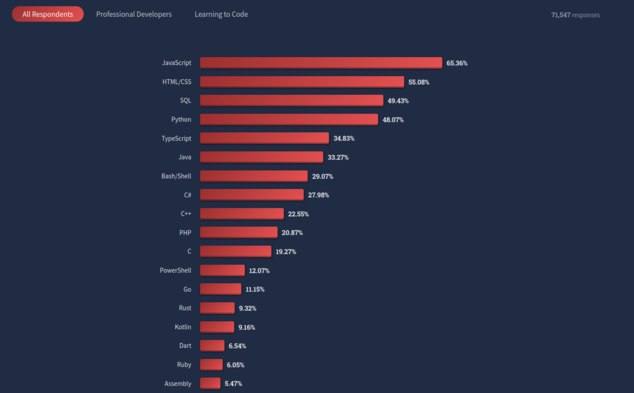

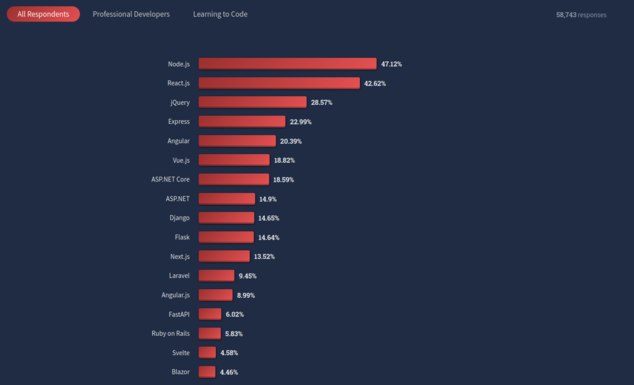

Web development in 2023Some interesting charts.

GitHub pull requests: https://madnight.github.io/githut/#/pull_requests/2023/2

TIOBE Index: https://www.tiobe.com/tiobe-index/

PYPL Index: https://pypl.github.io/PYPL.html

Stack Overflow survey: https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2022/#programming-scripting-and-markup-languages

Web frameworks: https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2022/#web-frameworks-and-technologies

It's clear that JavaScript dominates in web development, as expected, but Python is so strong in general that it's obviously not going away (the rise of AI has given Python an extra boost too). And among the web frameworks Django is only just behind the front-enders and Microsoft. -

Web development in 2023Instead of building a forum software from scratch, why not leverage and customize an open source option? Vanilla/Plush seems decent for your purposes, but you could self-host for much cheaper if you are able to provide the technical labor. NodeBB, Vanilla, Misago, Flarum, and Discourse are some of the open source options I looked at. Using NodeBB with the Lavender theme seemed like the best option for a philosophy forum, although Misago is also very clean. — Leontiskos

Yes, it’s the best option. I was only toying with the idea of building my own from scratch because I was getting back into development and wanted a meaty project. NodeBB and Discourse are the two I like the look of most. Vanilla is good too, but I don’t want to get involved with anything PHP (I know everyone says it’s great these days but my experience was traumatic). I’d never heard of Misago. Looks great, and codewise I like it better than NodeBB and Discourse, mainly because I like the combination of Python and JavaScript. I shall try it. Thanks for the tip :up:

On the state of things now and the future, I think you're both right and wrong. It's true that the front-end frameworks are the most visible and fashionable area of web development now—even non-developers I know have heard of React—but (a) people are realizing that on big projects where there's a lot of data involved, frameworks like Rails and Django perform better and are easier to maintain, (b) many are saying that things are moving back to the server frameworks now that the speedy front-end user experience of SPAs can be achieved, and with much less hassle, and (c) most front-end applications depend on an API built with something like Django anyway, so even when React is being used, something like Django is being used too. Some would say that this is for legacy reasons, but I actually think it's because Python is so strong right now, and getting stronger. Even if Django falls out of favour, other Python frameworks like FastAPI and Flask will take over. It's a lively area, though less visible than the front-end stuff.

(In fact, you could say that the existence of the big front-end frameworks is a consequence of legacy as much or more than the continuing presence of Django and Rails: browsers only understand JavaScript and there's no way out of that right now. In software terms, browsers are old technology, in which backwards-compatibility is a big issue.)

the older approach catered to a low barrier to entry, with languages like Ruby and Python being easy to learn — Leontiskos

It's because they're good-quality languages, and because they're powerful. And if Rails and Django seem easy at first, it's because they're well-designed frameworks and have been around a long time. React, Next.js, and Ember can be confusing because their way of working is intrinsically messy. It's painfully obvious that they're immature—although things are much better than when I started using them in 2013. Serious business logic behind the API endpoints is more often implemented in Rails and Django than it is with React and Node.

And the more that asynchronous JavaScript becomes an integral part of Rails and Django development—but without using big front-end frameworks—the more I expect to see them thrive. So I don't agree that robust back-ends are on the way out except where they were never really needed.

What we see is at the level of small-to-medium websites, the server-side frameworks have lost out, and that's probably as it should be. At this level, we have (a) static site generators or primarily static sites and immediate interactivity with asynchronous CRUD to a backend API, and (b) as you mentioned, website builders like Squarespace and Wix.

Yes, and I think this is why static HTML/Javascript is making a small comeback. — Leontiskos

Yes, I started using static site generators about ten years ago, and these days they're the norm for developers' own websites. The challenge was always how to integrate them with content management, but this can be done now, and paid blogging platforms may go in that direction. If we could only get non-devs to start writing everything in Markdown instead of WYSIWYG, life would be better.

There is a greater cognizance of maintenance and updating costs. In general it seems that the magnanimity of the tech boom is behind us. Cost and monetization loom larger than they once did when we were dazzled by the novelty and the low-cost-relative-to-the-past. — Leontiskos

Indeed. -

Web development in 2023See Cal Newport's Digital Minimalism for more on this. — baker

What does Cal say, and why do you think it's important? Is it something like, stop scrolling through Instagram and go for a walk instead? -

Web development in 2023And I don't know if it's me being old-fashioned, but there's something offensive about code like this:

export default function Blog({ posts }) { return ( <Layout home> <Head> <title>{settings.siteTitle}</title> </Head> <section className={styles.articleList}> <ul className={styles.list}> {posts.map((post, i) => ( <ArticleListItem post={post} key={i} /> ))} </ul> </section> </Layout> ); }

It's like doing classic ASP again. -

Theory of mind, horror and terror.I did not accuse anyone of fascism.

Now that the record is set straight, I'm leaving this discussion. No need for anyone to reply. Just get back to the topic or whatever. -

Theory of mind, horror and terror.If I am not wrong, one of the main guidelines of this site is to maintain the quality of the posts. I would rather be banned for being a 'fascist' rather than being ignorant. Agree, dear moderators? — javi2541997

Since all fascists are racist to some extent, being openly fascist is more likely to result in a ban than a lack of quality.

Now please, @javi2541997 and @universeness: enough of your bickering and name-calling. -

Currently ReadingThus giving it the excitement of a true story, while we all know it's not true.

-

Currently Reading

:up:

Seems to be saying that although what he writes is true, he can't give it verisimilitude. I don't know if he goes on to conclude that he has to fill in the gaps of memory with his inventions, or it's just Poe's narrative trick of saying "you're not going to believe this but I swear it's true." -

Why is alcohol so deeply rooted in our society?Why do humans want to escape their mind and avoid reality? How is it an advantage? — Skalidris

Some things are just a bonus.

Even elephants and monkeys were said to seek out and eat fermented fruit for its intoxicating powers. — Wayfarer

Small point: monkeys are more than just said to enjoy alcohol. It's been observed in wild situations, i.e., not just those monkeys stealing cocktails on the beach.

I didn't know about elephants though. A drunk elephant could do a lot of damage. -

Is it ethical to hire a person to hold a place in line?It would take a lot of money to persuade me to wait in a queue for someone. I can hardly wait in a queue for myself. I miss so many things owing to my fear of queues.

I should just start saying "line" cos writing "queue" is getting tiresome. -

What are you listening to right now?I’m not super into dance music except on rare occasions. That sounds ok. So…tentative agreement.

-

What are you listening to right now?I love rainy days — javi2541997

Me too. It's as if time stands still and allows you to contemplate the world unhindered.

-

Are you against the formation of a techno-optimistic religion?Cosmism — Bret Bernhoft

I don’t find the idea of a techno-optimistic religion either realistic or enticing, but I’m glad you started this discussion, because it prompted me to look into Russian cosmism, a weird spiritual-philosophical-scientific movement from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Some argue that it was cosmism that influenced the use of cosmonaut instead of astronaut (although there’s no particular reason why they should have chosen astro- anyway).

One cosmist was Alexander Bogdanov, a Bolshevik revolutionary who later formed a breakaway party independent of Lenin’s governing faction in the 1920s. He was a physician who experimented with rejuvenation by means of blood transfusions, hoping to attain eternal life, participated in politics, developed an early version of systems theory, and wrote a science fiction novel about a communist utopia on Mars, Red Star, which heavily influenced Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy.

The tone of some cosmism seems to be similar to your modern techno-optimism, though of course the technological focus has changed. -

Currently ReadingI don’t know what you mean ND. What’s digging for info got to do with the varieties of Brit?

EDIT: It’s either that I’m bad at conversation and thus find it hard to follow what you are saying, or you’ve had too much wine and are beginning to spout gibberish. Either way, it’s all cool, as they say. -

Currently ReadingAre the English people the English people? — Noble Dust

That’s one of the defining characteristics, yes. -

Currently ReadingBritish (is that the biggest umbrella? Can't remember) — Noble Dust

Scottish, Welsh, and English people are all British, but only one of the three groups is English. -

Currently ReadingWhat? Oh that. I’d forgotten all about it. Totally haven’t been seething with resentment for the last few fucking months.

Ok ND, I agree to be friends with you again, on condition you never mention my geographical location. -

Currently ReadingI'm currently reading Ocarle Night by Paul Auster. I seem to remember Jamal being an Auster fan, but not of this one. — Noble Dust

I said I don’t remember it, not that I didn’t like it.

It helps that I live a 20 minute walk from the neighborhood it took place in. — Noble Dust

:zip:

Jamal

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum