Comments

-

Why is the philosophy forum Green now?merely a random change-up based on being tired with the old purple colour — Benj96

:up:

No symbolism.

By the way I've moved this to the Feedback section. -

Ethics of Fox HuntingAn interesting alternative example to use is fishing, because fish are lacking in the furry cuteness that evokes our sentimental anthropomorphism.

I don't much like or approve of hunting for sport except for fishing, where you put the fish back alive, or else you kill it only so that you can eat it. So maybe the significant distinction, if there is one, is specifically the killing for sport, which is not a part of fishing. -

Pop Philosophy and Its Usefulness:lol: :up:

Embrace Your Contradictions: How Hegel’s Science of Logic Can Help You Achieve Wholeness by Owning Your Inner Conflicts -

Pop Philosophy and Its UsefulnessHow the Transcendental Doctrine of Elements Can Change Your Life.

Well, I am also in partial agreement. -

Pop Philosophy and Its UsefulnessUnfortunately the thing which distinguishes philosophy from self help and infotainment; argument and systems; is also something which makes philosophy unbearably dry. — fdrake

Isn’t philosophy, at its best, distinguished from self-help by its deep and original insights, rather than, or as well as, by its arguments? Self-help often strikes me as dishonest, manipulative, boring, and essentially individualistic, whereas good philosophy follows the ideas and respects the reader enough to think they can follow too.

My point here is that this actually makes it more exciting. Also, important philosophy is always critical and radical—again, exciting rather than dry.

Having said that, I guess there’s usually a barrier of dryness in presentation. -

Currently ReadingRereading Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason by Theodor Adorno, his introductory lecture course given in 1959.

Clear and deep and great fun to read, highly recommended for anyone interested in Kant, whether you’ve read the CPR or not (though some familiarity with the ideas is definitely required). -

Pop Philosophy and Its UsefulnessWas my initial reaction just an instance of snobbery, a kind of intellectual elitism? — Mikie

Is snobbery or elitism always bad? — Tom Storm

Having good taste isn't bad -- but probably being a snob is. — Mikie

Elitism judges the things, snobbery judges the person. Elitism holds up the best for everyone to see and appreciate if they can or want to, but snobbery merely holds up certain credentials as evidence of your superior status and the inferior status of everyone who is not in that class or in-group. Snobbery is always bad, but elitism isn’t.

In this case @Mikie, because you say, “I'd prefer my nephew (and anyone, really) read direct sources,” you’re an elitist but not a snob. You think the primary sources are the best and that your nephew has the potential to read and appreciate them.

On the other hand, Aristotle can be a chore to read, so there’s nothing wrong with making things more digestible. That’s why we read introductions and secondary literature. I think the crucial difference is that pop philosophy, unlike secondary literature, is often dumbed down, written to please people or to catch the attention or to sell books, not to enlighten or teach. -

You're not as special as you "think"The lack of replies would also lead me to believe no one really finds value in the OP so there's nothing to really learn. — Darkneos

I don’t think so. It’s a good OP. It just takes a bit more time and thought to reply to it compared to many others. I suggest you stop posting in this discussion if you don’t have anything intelligent to say. -

Currently ReadingOne that I found even more philosophical, but sort of sickeningly so, was The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch. If the majority of PKD novels feel like weird acid trips, that one was beyond the pale for me. I feel kind of scarred for life on that one, lol. — Noble Dust

This will have to be my next PKD :grin: -

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?... philosophy should seek its contents in the unlimited diversity of its objects. It should become fully receptive to them without looking to any system of coordinates or its so-called postulates for backing. It must not use its objects as the mirrors from which it constantly reads its own image and it must not confuse its own reflection with the true object of cognition. — Adorno, Lectures on Negative Dialectics

Here the significant dimension is concept/object, where the struggle is to get hold of objects without conceptualizing them. This is impossible to do in philosophy, but that's ok, because it's negative dialectics: it's trying to do what Wittgenstein said could not be done, though not with any naively hubristic metaphysical system.

From this perspective, an idea is a conceptual thing in a world of conceptual things called philosophy, or art or culture, or some other more granular "field of sense"--but the philosophical task is to uncover the real. This goes back to my first criticism: it's assumed by Adorno that the real is the material, whether the material is a table, or the relationship between an employer and an employee, or the freedom to flourish. And while these might have different strengths of conceptual flavour, that doesn't matter much, because this is historically relative and there is always in these cases something real in them. So probably the worst move to make is to try so hard to prove the realness of ideas that you invent a whole landscape out of them. That just confuses the concept/object dichotomy and reifies concepts unknowingly, thus obscuring the essential relationship between them. -

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?Yes, I agree unreservedly.

-

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?These questions were discussed long before science existed and are interesting in themselves. — Art48

As I said to Wayfarer, despite appearances what I was referring to was not so much ontology as such, or the problem of universals, degrees of reality in Platonism, and so on, but more about the motivations behind the particular ways these ideas appear in contemporary concepts, like the mindscape. -

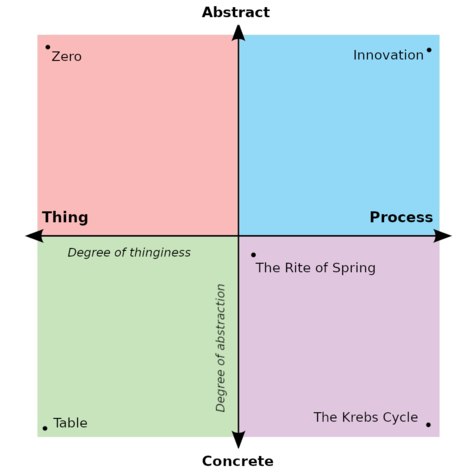

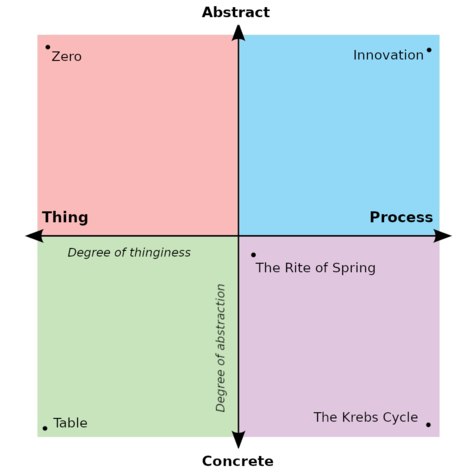

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?So there’s a scale of thingyness and an independent scale of abstractness. — Jamal

I like considering more than one dimension. — green flag

Two might not be enough but it's better than one, so I made a 2D ontology chart, without much thought as to how pointless or wrongheaded it might be.

-

An example of how supply and demand, capitalism and greed corrupt eco venturesThis thread has an identity crisis. May I suggest...

"An example of how supply and demand, capitalism and greed corrupt eco ventures, plus what is God?" -

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?Sure, but I was mostly referring to the focus on “exists”.

-

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?I think instead of saying math isn't in space and time we should say that math methodically ignores the actual, local spatial and temporal situation — green flag

I find that agreeable, but mathematical Platonism is rampant around here.

Are numbers and other abstract objects universals, and are universals real? Old questions.

Whatever the answers, I’m quite happy to say numbers and properties exist, along with thoughts and tables even in the case that they are abstract and dynamic. This is because to say that something exists isn’t to say all that much. It just sets things up (semi-literally) so you can deal with them. I see being in the same way. I can’t shake the thought that the controversies over what exists are motivated by a fear of irrelevance in the face of physical science. Otherwise, why worry?

EDIT: if there seems to be an anti-philosophical note at the end there, it’s just in the way of provocation. -

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?

Ideas, meanings, and thoughts are just not very thingy, are they? The static ontology of medium-size dry goods doesn’t feel right. (Some would say that a static ontology doesn’t even work for them either, which I suppose is process metaphysics.)

But numbers are more thingy than thoughts, while at the same time being not or less mind-dependent, and not situated in space and time. So there’s a scale of thingyness and an independent scale of abstractness. -

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?Yep, I do understand. I just couldn't see the point of making the distinction in the way you

and Russellwant to make it. For me, all these things exist. In logical terms, existence quantifies over a domain of discourse. That could be e.g., the domain of natural numbers or the domain of fictional characters (what about the domain of universals? :chin:).

Although to be honest, I'm more interested in ideas and thoughts than I am in universals and abstract objects, because that's what seems most radical/incredible about the concept of the mindscape. -

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?Whereas, what I'm arguing is that I think the very idea of there being 'degrees of reality' is no longer intelligible. So there are no 'different ways' in which things can exist - we say that things either exist, or they don't. Tables and chairs exist, unicorns and the square root of 2 do not. — Wayfarer

Again, you are conceding that the gold standard of existence is that of physical objects. You seem to accept physicalist assumptions perhaps without realizing it. Because to say that something exists in a certain way is not to say it is more or less real than things that exist in a different way.

Russell says "we shall find it convenient" to say of universals that they subsist, and not that they exist, but it's not much more than one way of making the distinction. It's a concession to physics to say that only things that are in time exist.

And do you accept his classification, wherein ideas do exist, and it's only universals that don't? -

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?Yes, but why concede to the physicalists that the things of the third realm don't exist?

So as not to lose sight of the differentiation, I suppose. But another way of paying attention to the differentiation is to say that something exists in a different way. My question is what the difference is between these terminological choices.

I think it's a concession to both reductionism and reification to accept that only physical objects exist. That's partly what motivated Markus Gabriel's ontology, in which tables, quarks, numbers, nations, and ideas all exist. There are alternative theories that do the same kind of thing, like critical realism and speculative realism.

He believed that these abstract objects existed independently of the physical world and the mind, and that they had a different kind of reality that was not reducible to either physical or mental phenomena. — Wayfarer

But you want to go one step further and say they don't exist? -

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?they don't exist, in the sense that chairs and tables and other objects of perception exist — Wayfarer

What’s the difference between saying they exist in a different way, and saying they don’t exist but they’re real? What have you got against the use of “exist” for ideas, numbers, etc.?

What about nations and conversations?

If both tables and numbers are real, but only tables can also be said to exist, then it looks like you’re downgrading numbers just because they’re not objects of physical science.

I think @Art48 is right to question your terminological critique. -

What are your philosophies?If you are interested in those particular philosophical topics, then it would be great if you started discussions about them. But note that what is in this thread is just an informal Lounge chat.

-

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?That's the bit I have trouble with. Establishing the mind-independent existence of abstract objects (numbers) might be hard enough, but establishing the same for particular ideas is a big step beyond even that, is it not?

-

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?I agree, and never intended for mindscape to denote a literal place in spacetime — Art48

But you did intend it to denote a literal domain of existence in which ideas exist eternally and independently of minds, yes? -

Where do thoughts come from? Are they eternal? Does the Mindscape really exist?Off the top of my head...

Maybe I can go along with an ontological pluralism in which ideas can be said to exist in their own domain, but they would exist in a different way from stars and brains (which is just/also to say that "exist" has different meanings in different domains, as @Banno has pointed out).

As @green flag said, we can use concepts like lifeworld or culture, and maybe the manifest image is along the same lines. I'll add another one that's more granular and ontological: fields of sense. This is Markus Gabriel's concept: a field of sense is a context, domain, or background in which or against which something stands out, and thereby exists.

So ideas exist in their own domain. Very well. But what is happening to this concept when it turns into the mindscape? What justifies this leap? On the face of it, it's a wildly speculative reification that attempts to turn, say, an analogical way of thinking about ideas, one that's familiar to artists and geniuses, into a mind-independent ontology: not only do ideas exist, but they have always existed, and we tap into the mindscape to think them. But in fields of sense or the lifeworld, we might say that ideas exist, but we do not thereby establish eternal existence independent of people, because these domains are strictly human and finite realities, and I can't see the justification for the leap, at least not in the OP (I haven't read all of Rucker's online presentation of the idea).

Is this what happens when you combine the thought of a universe of physical objects with the thought of universals and abstract objects like numbers, as I think @Wayfarer is suggesting?

So you end up with something like Platonism I guess, although as far as I can tell the existents of the mindscape seem to be concrete and/or particular, rather than being merely universal forms: in this mindscape there are instantiations, like Macbeth, and not only forms.

On the other hand, the idea of a shared landscape of ideas is an attractive one, but only as at least part-analogical--there may be a world of ideas that we are part of when we think, but it's more map than landscape (but this might be in conflict with ontological pluralism, I'm not sure). -

What are your philosophies?It’s been bothering me that I didn’t answer those questions. I am interested in questions 1, 5, and 7, so I’d like to come back to them some time. But as I say, they’re for the main philosophy sections, not the Lounge, so maybe I’ll start a new discussion there if I get the time. Or if you feel like it, start a new discussion on hinge certainties or historicism (probably in Metaphysics & Epistemology and General Philosophy, respectively).

Questions 2, 3, and 4: those I cannot answer. For instance, I have not read those works that argue against direct realism, and when I said I was for externalism it seems I was bullshitting or perhaps was once in favour of it but have now forgotten the debate.

But I’ll answer 6 directly: I agree. -

What are your philosophies?If I’d known you were going to ask difficult questions I wouldn’t have posted :grin:

Some other time perhaps. Each one deserves a main page discussion of its own and I don’t currently have enough interest or knowledge to answer them all. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Our senses (body and mind) filter, organize and present information (data) from the external enviroment in a way that is advantageous (usually) for our survival. Do our senses give us an entirely complete picture of the external environment, it would seem quite clearly not; we don't see UV or Infrared, we do not hear frequencies above or below certain limits. So our picture of the world including the way we color it is a representation of reality, not a complete picture of all or nature. — prothero

Your conclusion doesn’t follow. Another possibility which is consistent with the premises is this: we see things in certain human ways, but it’s the things we are seeing, not representations thereof. That’s direct perception. -

What are your philosophies?Welcome to TPF Ø, good to have you on board :smile:

I never think of myself as having a philosophy. That way of putting it feels foreign to me. And in fact, I neither know how to describe my general philosophical position nor whether I even have one. But let’s see how it goes…

I started this site as a replacement for an older site that fell apart. I was a moderator there towards the end, and now I’m one of three administrators here at TPF. Like Tom, I have no formal training in philosophy. Depending on how you look at it, I’m a Renaissance man or a mere dilettante, but when I’m into philosophy—it comes and goes—I take it somewhat seriously. After having read some Marx and Hegel in my late teens, when I was a member of a weird Trotskyist cult, I dropped philosophy until about fifteen years ago, when I joined the predecessor of this site. I taught myself some logic, read Plato, Descartes, Wittgenstein, Austin and Ryle, studied the Critique of Pure Reason for many months, read Foucault and Husserl and Merleau-Ponty and a bunch of other things. Now, after five years without much interest in philosophy, I’m into early critical theory and may even come back around to tackling Hegel at some point.

On what there is, I’m a non-reductive materialist. I also think there’s always something left out of our perception and conceptualization, i.e., something that escapes the human world while also underlying it (though “underlying” seems like the wrong word), which could be described as the Real, the non-identical, or the unconditioned, depending on your theory. This is how I attempt to be a proper realist while giving Kant his due.

On perception, I sometimes describe myself as a direct realist, but sometimes I reject that label and advocate embodied cognition, enactivism, ecological perception and so on, in an effort to sidestep the interminable (on TPF at least) debate between direct and indirect realism.

On knowledge and the mind I’m with externalism, enactivism, and embodied cognition, and I’m a big fan of Wittgenstein’s contribution here too. I’m aware that I just reduced epistemology and the philosophy of mind to one sentence.

Politically I tend to think in quasi-neo-Marxian terms but I don’t like most Marxisms. Political and social philosophy is my main philosophical interest at the moment, where I feel most affinity with philosophers like Adorno. I think that capitalism is the most powerful and most flexible in a long line of social forms based on domination and exploitation and the curtailment of human freedom, creativity and flourishing. I also think that modernity has produced, and could still produce more, non-capitalist social forms that are similarly based on oppression. I believe this is a difficult problem.

Generally I believe that history is more important to philosophy than most philosophers have understood and I am impatient with philosophical theories that are clear outgrowths of their historical conditions—like Descartes and the centuries of representationalism that followed—even though I accept (sometimes) that in philosophy, theories cannot be rejected merely by pointing to their historico-ideological nature. I might start a discussion about this one day, i.e., about historicism.

On God and religion, again I think somewhat anti-philosophically about it: I take it for granted that it’s an anthropological and historical phenomenon, and I have no interest in debating or thinking about God’s existence. So by default I’m an atheist, but I respect and value aspects of religious and spiritual thinking and see no need to fight against religion per se.

On meta-ethics I go for something like a social naturalist moral realism, which plays out normatively as virtue ethics. And I go back to early Marx here for some sort of humanism and a focus not only on the social nature but also on the essential (there I said it) creativity of human beings.

In general for: the body, society, history, creativity, human flourishing and endless criticism.

In general against: Cartesian theories of perception and the mind, ahistorical and asocial philosophy, idealism, greedy reductionism, and stupidity.

I’ve avoided logic, truth, mathematics, science, and language, either because I haven’t decided where I stand or because I don’t know the issues well.

and if you want to create a behemoth of text, that is also fine — Ø implies everything

Et voila. -

Does value exist just because we say so?You misunderstood. I did not say that worldviews or metaphysics or epistemology are not substantial. I said that we were not having a debate over anything substantial, but merely exchanging worldviews.

-

Eternal ReturnTry to imagine the best in people before you settle on nasty. — frank

Try to take my comments about your behaviour seriously. You really haven’t absorbed it at all. -

Eternal ReturnWow, you really misread that — frank

That’s how I read it too. You were asked to justify what you said and instead of answering you assumed a posture of superior knowledge to completely dismiss your interlocutor. -

Does value exist just because we say so?Well, I’m not sure how we ended up just exchanging worldviews rather than arguing about something substantial, but I did find that quite interesting, and I’m glad to see we are still entirely opposed on the big philosophical issues.

-

Eternal ReturnI won’t address the metaphysical issue—and it’s highly debatable in Nietzsche scholarship how significant that issue is—but I thought I’d step in to quote the first appearance of the idea in Nietzsche’s work:

What if one day or night a demon came to you in your most solitary solitude and said to you: ‘This life, as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live again, and innumerable times again, and there will be nothing new in it; but rather every pain and joy, every thought and sigh, and all the unutterably trivial or great things in your life will have to happen to you again, with everything in the same series and sequence – and likewise this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and likewise this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence will be turned over again and again, and you with it, you speck of dust!’

Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke to you thus? Or was there one time when you experienced a tremendous moment in which you would answer him: ‘You are a god, and I have never heard anything so divine!’ — The Gay Science, §341

So here at least it’s a thought experiment to test one’s attitude to life. And in the later work, Zarathustra eventually comes to welcome the prospect of an eternal return—passing the test, so to speak.

Jamal

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum